Abstract

This pictorial review focuses on basic procedures performed within the field of podiatric surgery, specifically for the hallux abductovalgus or “bunion” deformity. Our goal is to define objective radiographic parameters that surgeons utilize to initially define deformity, lead to procedure selection and judge post-operative outcomes. We hope that radiologists will employ this information to improve their assessment of post-operative radiographs following reconstructive foot surgeries. First, relevant radiographic measurements are defined and their role in procedure selection explained. Second, the specific surgical procedures of the distal metatarsal, metatarsal shaft, metatarsal base, and phalangeal osteotomies are described in detail. Additional explanations of arthrodesis of the first metatarsal-phalangeal and metatarsal-cuneiform joints are also provided. Finally, specific plain film radiographic findings that judge post-operative outcomes for each procedure are detailed.

Keywords: Podiatric surgery, postoperative outcome, hallux abductovalgus, bunion, radiography, metatarsal osteotomy

REVIEW

The intention of this pictorial review is to present radiologists with a basic overview of common procedures performed within the field of podiatric foot and ankle reconstructive surgery. This article specifically focuses on the hallux abductovalgus deformity. Our goal is to emphasize radiographic findings that surgeons utilize to judge post-operative outcomes, but we will also review the pre-operative radiographic parameters that initially define the deformity and lead to procedure selection. It is our hope that radiologists will employ this information to improve their ability to assess post-operative radiographs following foot and ankle reconstructive surgeries.

Pre-operative planning

Hallux abductovalgus (HAV, or the “bunion”) is one of the most common podiatric forefoot complaints. The deformity is objectively defined with plain film radiography, primarily in the transverse plane with the weight-bearing anterior-posterior (AP) or dorsal-plantar (DP) foot projection (See Figure 1). Because nearly all foot and ankle deformities have a dynamic biomechanical component, it is important to always evaluate the deformity with only weight-bearing radiographs taken in the angle and base of gait [1]. Non-weight bearing views will often underestimate the degree of deformity and are generally considered to be inappropriate if used for procedural selection. With that being said however, it is important to appreciate that most post-operative radiographs will be ordered as non-weight bearing views in order to protect the surgical site.

Figure 1.

Weight-bearing DP plain film radiograph of a 34 y/o female presenting with a complaint of medial first metatarsal head pain consistent with HAV deformity. Line A is a longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal; Line B is a longitudinal bisection of the second metatarsal and Line C is the longitudinal bisection of the hallux proximal phalanx. The 1st intermetatarsal angle (IMA) represents the angular relationship between Lines A and B with a normal range between 0–8 degrees (increased to approximately 12 degrees here). The hallux abductus angle (HAA) represents the angular relationship between Lines A and C with a normal range between 0–15 degrees (increased to approximately 30 degrees here). And the metatarsal-sesamoid position (MSP) is the positional relationship between Line A and the tibial sesamoid (increased to approximately position 5 here, as defined in Figure 2). The findings in this radiograph are consistent with a mild to moderate HAV deformity.

Although there are many measurements that are performed by podiatric surgeons pre-operatively for procedure planning and post-operatively for surgical assessment, the three primary measurements are the 1st intermetatarsal angle (1st IMA), hallux abductus angle (HAA) and metatarsal-sesamoid position (MSP) (Figure 1). All three measurements are based on a longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal [1–5]:

The 1st IMA is the resultant angle between a longitudinal bisection of the 1st metatarsal (Line A) and the longitudinal bisection of the 2nd metatarsal (Line B). The normal value of this measurement ranges from 0–8 degrees, with a greater angle indicating greater deformity.

The HAA is the resultant angle between the longitudinal bisection of the 1st metatarsal (Line A) and the longitudinal bisection of the proximal phalanx of the hallux (Line C). The normal value of this measurement ranges from 0–15 degrees, with a greater angle indicating greater deformity.

The MSP is the relationship between the longitudinal bisection of the 1st metatarsal (Line A) and the position of the tibial sesamoid. This is typically measured on a 7-point scale (Figure 2), and normal is a position of 1–3 [5,6].

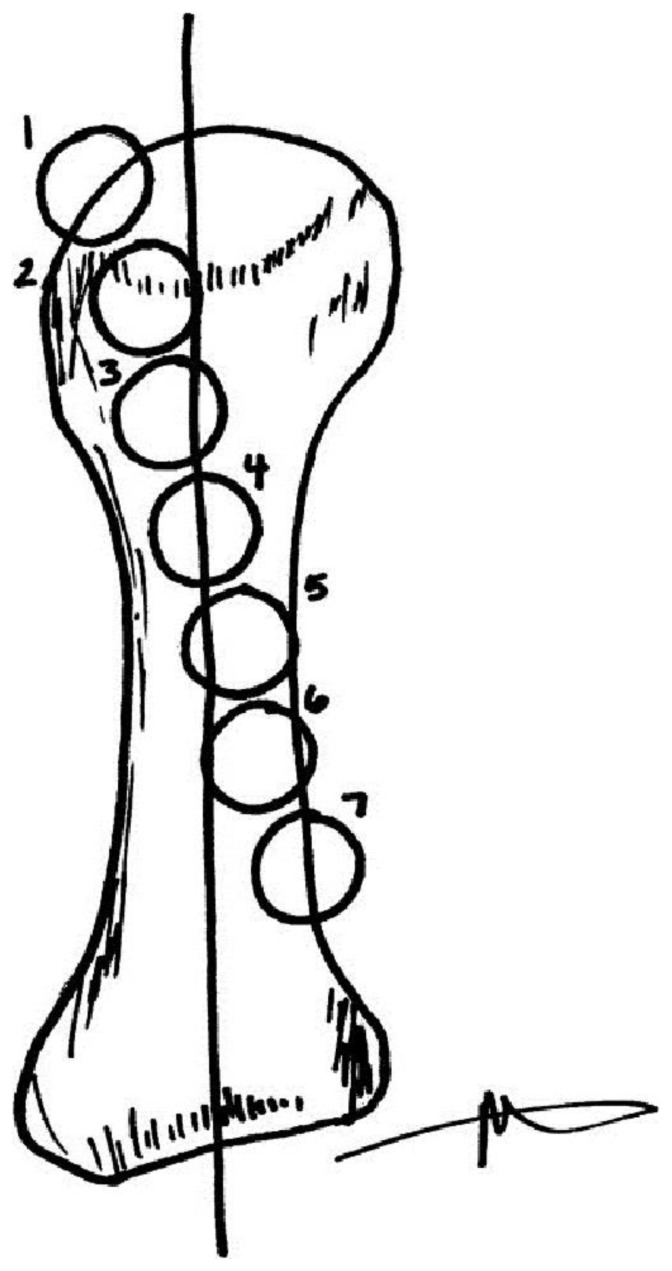

Figure 2.

The metatarsal-sesamoid position is typically measured on a 7-point scale and increases with progressive deformity of the first metatarsal in a medial direction. In a well-aligned 1st metatarsal-phalangeal joint, the tibial sesamoid lies completely medial to the longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal, whereas with significant deformity the tibial sesamoid may lie completely lateral to the longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal. It may help to visualize the sesamoids lying in the stationary position while the metatarsal translates off of them medially during deformity progression, and then the surgical procedure moves the metatarsal back on top of them during deformity correction.

[Figure reprinted with permission from Ramdass R, Meyr AJ. The multiplanar effect of first metatarsal osteotomy on sesamoid position. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010 Jan–Feb; 49(1): 63–7.]

In the past, these measurements were physically drawn on radiographs by surgeons and measured with a protractor, but advancements with digital radiographs allow for automatic measurements and calculation of these angles. It is interesting that there is no accepted objective measurement of the resultant clinical so-called “bump” of the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head, and this is not used to either define the deformity or for procedural selection [2]. The choice of procedure within the first metatarsal depends on the severity of the deformity, with more severe deformities generally requiring more proximal osteotomy or first tarso-metatarsal arthrodesis.

Distal First Metatarsal “Head” Osteotomies: Austin/Chevron Procedure

There are literally >100 procedures described for the surgical correction of the HAV deformity, but all can be classified based on the anatomic site of intervention [3]. More mild deformities are typically treated with distal metatarsal osteotomies or “head” procedures. The most common of these is the Austin or Chevron osteotomy (Figures 3–5) [7,8]. This is a “V” shaped osteotomy performed in a medial to lateral direction within the center of the first metatarsal head. The dorsal and plantar osteotomy arms were initially described to be of the same length, but the dorsal arm is now usually cut longer to accommodate for screw fixation [9]. The capital (or distal) fragment is then translated laterally and affixed with screws or pins.

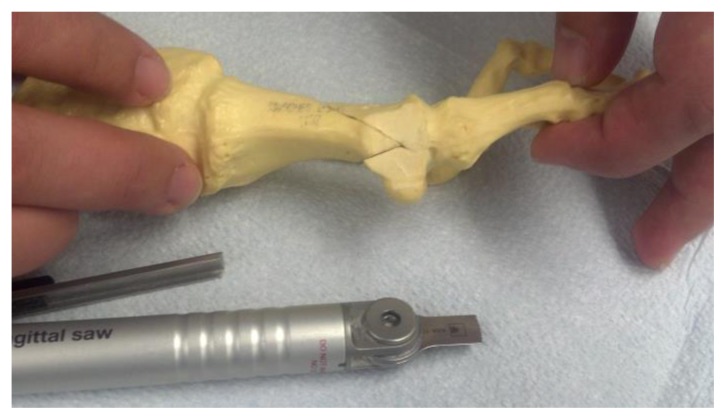

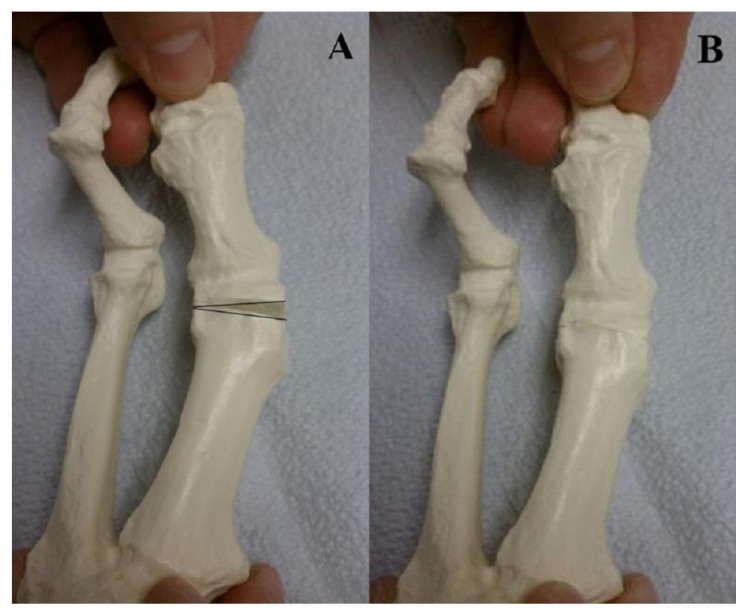

Figure 3.

For a distal first metatarsal osteotomy, a “V” shaped osteotomy is performed with a sagittal saw within the head of the first metatarsal. Usually, a longer dorsal arm is created to accommodate for screw fixation and increase the osseous contact area.

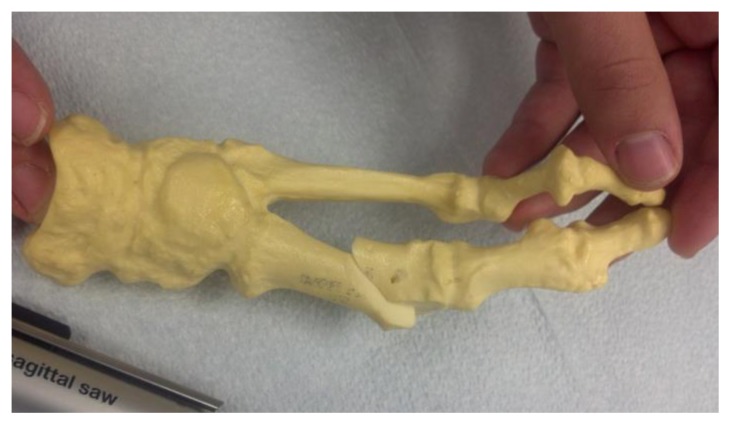

Figure 4.

The capital fragment is then translated laterally to correct for the increased 1st intermetatarsal angle. Following fixation of the osteotomy, the remaining overhanging shelf of bone is resected to form a smooth medial surface of the metatarsal.

Figure 5.

One or two screws can then be inserted across the dorsal arm of the osteotomy for fixation. Generally speaking, screws are inserted perpendicular to an osteotomy in order to produce the most stable construct possible.

Figure 6 is the post-operative radiograph of the patient from Figure 1 following a distal first metatarsal osteotomy. One can appreciate appropriate reduction of the 1st IMA, HAA and MSP to within normal ranges. This particular osteotomy was modified to include a longer dorsal arm to accommodate screw fixation, and in this case two bicortical screws were utilized. With bicortical fixation, it is important to check a lateral projection for screw length and location (Figure 7). In this anatomic area, one can appreciate that the bicortical screws are angulated proximally to avoid penetration into the metatarsal-sesamoid articulation. Another important consideration is that it is acceptable to have several screw threads protruding through the plantar cortex as shown in Figure 7. Figure 8 is an example of a screw that is on the border of being considered “too long” in terms of its plantar soft tissue penetration.

Figure 6.

Post-operative AP radiograph of the 34 y/o female from Figure 1 status post surgical correction of the deformity. One can appreciate reduction of the 1st IMA, HAA and MSP to within normal ranges. Note how the medial aspect of the tibial sesamoid is now in complete alignment with the medial surface of the first metatarsal. Additionally, two parallel screws can be appreciated crossing the osteotomy within the first metatarsal head. These radiographic findings are consistent with appropriate post-surgical changes following distal first metatarsal osteotomy for correction of the HAV deformity.

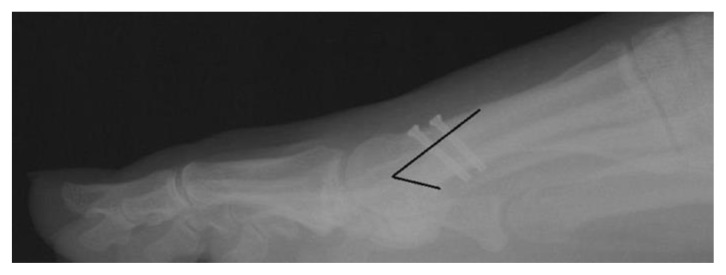

Figure 7.

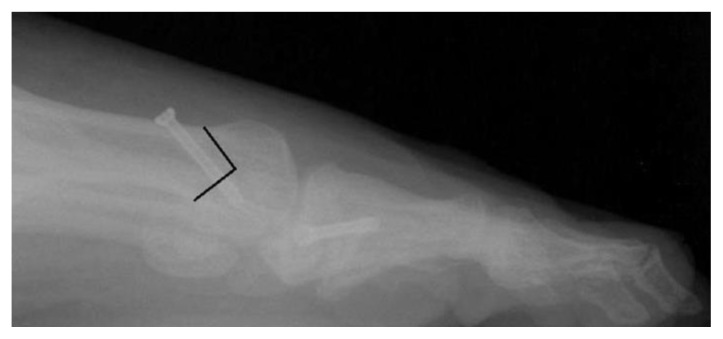

Post-operative weight-bearing lateral radiograph of the 34 y/o female from Figure 1 status post surgical correction of the deformity. On this lateral view, one can appreciate that two bicortical screws were inserted perpendicular to the osteotomy and angled away from the metatarsal-sesamoid articulation. One can also appreciate appropriate length on these two screws with several thread lengths penetrating the plantar cortex of the metatarsal. The black line on the image emphasizes the location and shape of the performed osteotomy.

Figure 8.

Post-operative weight-bearing lateral radiograph of a 52 y/o female status post surgical correction of a HAV deformity. Again, the black line on the image emphasizes the location and shape of the performed osteotomy. This radiograph demonstrates a screw that is on the threshold of being considered “too long” with extension of the screw past the plantar metatarsal cortex into the plantar soft tissue.

Figures 9–11 demonstrate several of the other common fixation techniques when bicortical screws are not utilized. There are nearly as many ways to fixate a distal first metatarsal osteotomy as there are variations of the procedure itself [2,3,7–9]. A single cancellous screw may be used with the distal portion of the screw ending within the cancellous portion of the metatarsal head (Figure 9). Percutaneous (Figure 10) or buried (Figure 11) Kirshner wires (K-wires) may also be inserted. These are usually 0.062″ in diameter when used for this purpose. And finally, it is interesting to point out that the procedure was originally described with no fixation at all due to the inherent stability of the osteotomy [7]!

Figure 9.

Post-operative weightbearing lateral radiograph of a 28 y/o male following a forefoot surgical correction. In this case a single cancellous screw was inserted to fixate the distal first metatarsal osteotomy (in addition to a hallux phalangeal procedure). Because of the distal orientation of the screw, it is important to note that the screw ends well within the cancellous portion of the metatarsal head, and not the adjacent joints. This orientation allows for screw fixation when a longer dorsal osteotomy is not utilized.

Figure 10.

This AP post-operative radiograph demonstrates a distal first metatarsal procedure fixated with a percutaneous K-wire. This is an acceptable form of fixation and is typically removed after a period of several weeks. Proper position of the K-wire entails that it is free of adjacent joints and avoids soft tissue structures. (Image courtesy of Jane Pontious, DPM FACFAS)

Figure 11.

This oblique post-operative radiograph demonstrates a distal first metatarsal procedure fixated with a buried K-wire. This is an acceptable form of fixation and the K-wire may be permanently left in place as long as it is asymptomatic. (Image courtesy of Jane Pontious, DPM FACFAS)

Distal First Metatarsal “Head” Osteotomies: Reverdin Procedure

Another common head procedure involves rotation of the articular cartilage on the head of the first metatarsal. In the presence of a long-standing HAV deformity, the articular cartilage may rotate laterally to adapt for the new position of the hallux proximal phalanx. Although an objective radiographic relationship has been described between the longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal and the articular cartilage on the first metatarsal head, most surgeons rely on intra-operative findings to determine whether rotation of the articular cartilage is required (Figure 12 and 13) [1–4]. The Reverdin procedure involves the removal of a medially-based dorsal wedge from the head of the first metatarsal for realignment of the articular cartilage (Figure 14) [10]. This procedure is typically fixated with either a single cancellous screw or K-wire.

Figure 12.

Pre-operative weight-bearing AP radiograph of a 28 y/o male complaining of a painful bunion deformity with associated metatarsus adductus deformity demonstrating pre-operative evaluation for the Reverdin osteotomy. Note the deviation of the articular cartilage on the head of the first metatarsal in this patient with long-standing HAV deformity as highlighted by the two arrows. The larger vertical arrow represents the current most medial aspect of the articular cartilage, while the smaller horizontal arrow represents the likely location of the most medial aspect at the beginning of the deformity. Although cartilage deviation of the head of the first metatarsal can often be appreciated pre-operatively with radiographs, surgeons will most often make this assessment based on the intraoperative clinical appearance.

Figure 13.

Post-operative weight-bearing AP radiograph of the 28 y/o patient in Figure 12 following a Reverdin osteotomy within the head of the first metatarsal (among other procedures). Note the realignment of the articular cartilage on the head of the first metatarsal in line with the long axis of the first metatarsal shaft compared to the pre-operative view.

Figure 14.

The Reverdin procedure involves resecting a medially-based wedge of bone from the metatarsal head in the setting of long-standing cartilage deviation. When the osteotomy is brought together, the articular cartilage is now well-aligned with the long axis of the first metatarsal. This procedure will primarily have an effect on the HAA.

First Metatarsal “Shaft” Osteotomies: Scarf Procedure

Moderate HAV deformities are typically treated with “shaft procedures”, or osteotomies that are centered about the metatarsal shaft. The most common of these is the scarf osteotomy (Figures 15 and 16) [11]. A longitudinal osteotomy is made from medial to lateral within the shaft of the metatarsal, with proximal and distal oblique arms for completion. The capital (distal) fragment is then translated laterally and affixed with two screws. Osteotomies within the metatarsal shaft and base are typically used for correction of moderate to severe deformity.

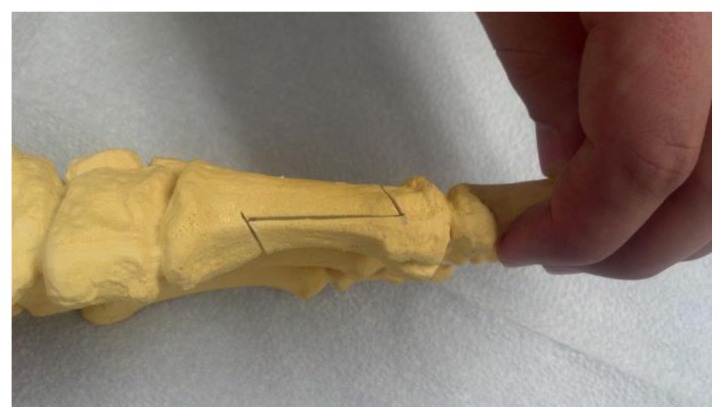

Figure 15.

The scarf osteotomy is composed of a long longitudinal osteotomy from medial to lateral within the metatarsal shaft with a proximal and distal oblique arm for completion. The “Z” shape and oblique angles of the proximal and distal arms add a level of intrinsic stability to the osteotomy.

Figure 16.

The capital fragment is then translated laterally to correct for the 1st IMA. Two screws are typically utilized to stabilize the osteotomy.

Figures 17a–c demonstrate the pre- and post-operative radiographs of a patient following a scarf shaft procedure. The pre-operative DP radiograph demonstrates increases in the 1st IMA (approximately 15 degrees), HAA (approximately 23 degrees) and MSP (approximately 5). Post-op radiographs demonstrate reduction of radiographic parameters to the normal range. On the lateral view, appropriate orientation and length of the bicortical screws can be appreciated.

Figure 17.

This series of images illustrates the surgical correction of a HAV deformity in a 63 y/o male patient. Figure 17a represents the pre-operative weight-bearing AP view of the right foot with apparent increases in the 1st IMA (approximately 15 degrees), HAA (approximately 23 degrees) and MSP (approximately 5). These findings are consistent with a moderate HAV deformity. Figure 17b is the post-operative weight-bearing AP view which demonstrate reduction of radiographic parameters to their normal ranges. Figure 17c shows the post-operative weight-bearing lateral view where appropriate orientation and length of the bicortical screws can be appreciated.

First Metatarsal “Base” Osteotomies: Closing Base Wedge Procedure

Severe deformities are treated with procedures within the base of the first metatarsal, or with arthrodesis of the first metatarsal-cuneiform articulation. A common “base” procedure is the closing base wedge osteotomy (CBWO), which consists of an oblique, laterally based wedge within the proximal metatarsal (Figures 18 and 19) [12]. Fixation of this procedure is performed with at least one bicortical screw perpendicular to the osteotomy.

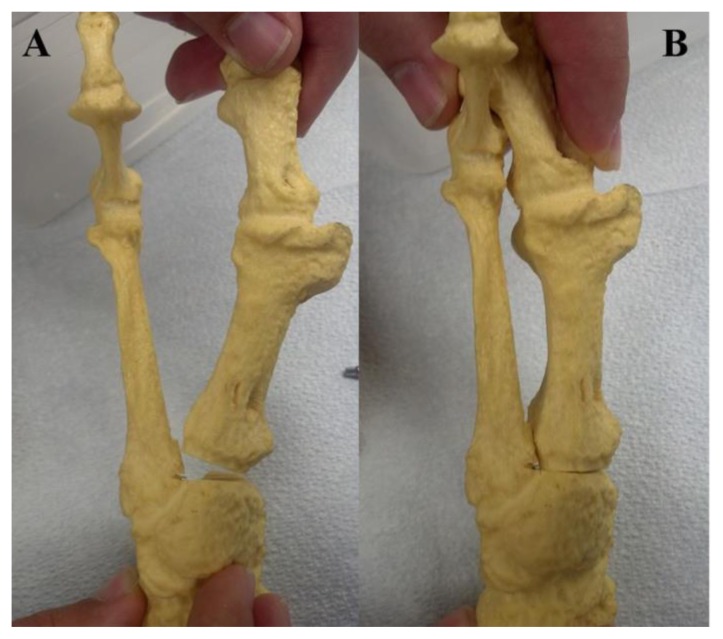

Figure 18.

The closing base wedge osteotomy involves resection of a laterally based wedge of bone from the base of the metatarsal. As the osteotomy is closed down and temporarily held in place with a clamp, one can appreciate the lateral translation of the first metatarsal and visualize reduction of the 1st IMA as the first metatarsal is pulled into alignment with the second metatarsal.

Figure 19.

These pre- and post-operative weight-bearing AP radiographs demonstrate the surgical correction of a HAV deformity with a closing base wedge osteotomy in a 49 y/o female patient. A black line has been superimposed on the post-operative image to demonstrate the location and orientation of the osteotomy. One can appreciate that two screws have been positioned across the osteotomy where the laterally based wedge was resected and closed down. The lateral aspect of the shaft of the first metatarsal now shows a small “step-off” which is consistent with a closing base wedge osteotomy. (Radiographs courtesy of Dr. Joshua Moore, DPM.)

First Metatarsal “Base” Osteotomies: Lapidus Arthrodesis

Another option for correction of severe deformities is arthrodesis (or fusion) of the first metatarsal-cuneiform articulation. Arthrodesis of this joint is commonly referred to as the Lapidus procedure [13], and may be fixated with screws, a plate or external fixation. By resecting a laterally-based wedge from the articular cartilage of both the first metatarsal base and medial cuneiform, powerful correction of the 1st IMA may be achieved (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

In a Lapidus arthrodesis, the articular cartilage is resected from the base of the first metatarsal and anterior aspect of the medial cuneiform. A wedge of bone can be removed laterally to correct for an increased IMA.

Figures 21 demonstrate pre- and post-operative radiographs of a Lapidus procedure. Note the significant degree of correction that can be achieved with this procedure, with a near parallel 1st IMA post-operatively. In this particular case the IMA decreased from approximately 16 degrees pre-operatively to 0 degrees post-operatively.

Figure 21.

Pre- and post-operative radiographs of a 23 y/o female with a HAV deformity corrected with a first metatarsal-medial cuneiform arthrodesis (among other hammertoe procedures.) Figure 21a represents the pre-operative weight-bearing AP view of the left foot with increases in the 1st IMA, HAA and MSP which have been reduced to within their normal ranges on the post-operative weight-bearing AP view in Figure 21b. In fact, one can appreciate the near parallel relationship between the first and second metatarsals on the post-operative view. The arthrodesis has been fixated with two crossing screws at metatarsal-cuneiform joint level, with two K-wires used for fixation of the hammertoes of digits two and three. On the post-operative lateral view (Figure 21c), note the parallel relationship between the longitudinal axes of the talus and first metatarsal. Also note that the distal-to-proximally oriented screw appears to penetrate the navicular-cuneiform joint on the AP view, but is appreciated to be clear of this joint when viewed from the lateral projection (see arrow).

Post-operatively, one must note the position of the screws, particularly proximally to ensure that the screw does not impede upon the navicular-cuneiform joint. This is best appreciated on the lateral view. Also on the lateral view (Figure 21c), the angle between the long axes of the talus and first metatarsal should be appreciated. This should be a near parallel relationship and any relative dorsiflexion of the first metatarsal is noted to be a complication.

Hallux Phalangeal Osteotomies: Akin Procedure

An adjuvant procedure that is often performed if adequate correction of the HAA has not been achieved is the Akin phalangeal osteotomy [14]. This is a medially based wedge performed through the proximal phalanx of the hallux and can provide an additional level of deformity correction if needed (Figure 22).

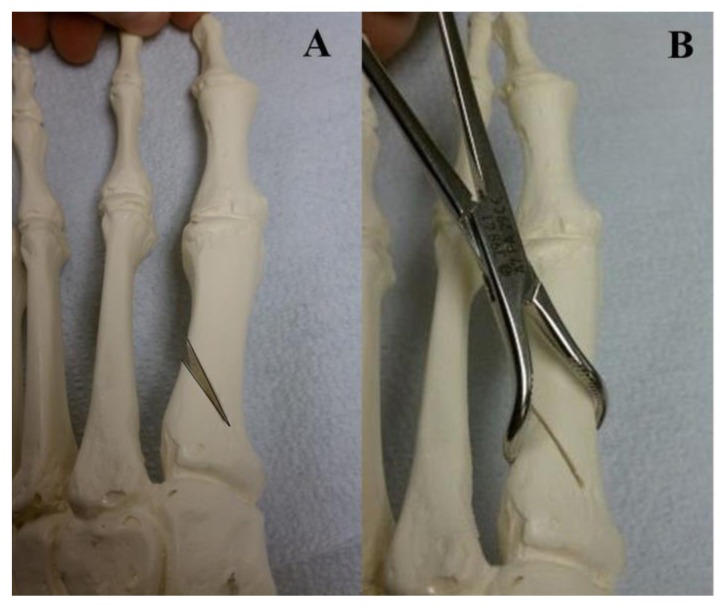

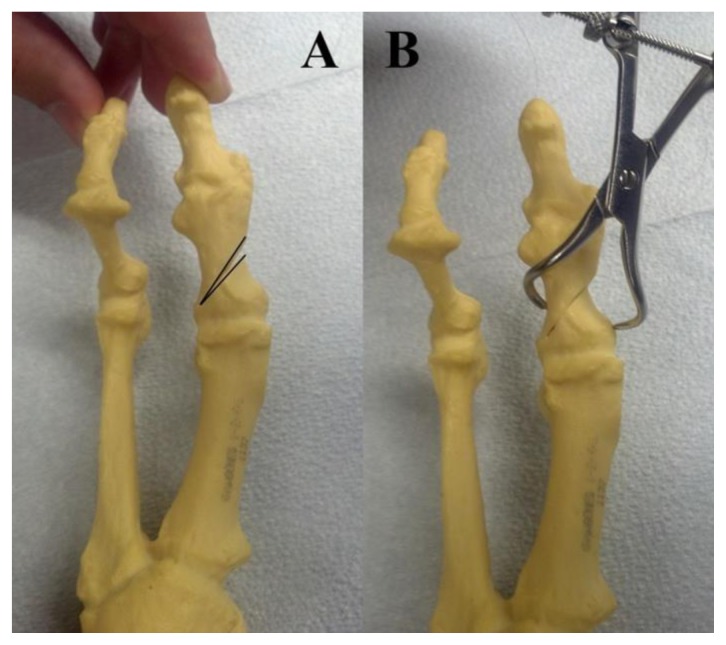

Figure 22.

The Akin osteotomy is a medially based wedge within the proximal phalanx of the hallux. A clamp is used to temporarily close down the osteotomy which aligns the hallux on top of the first metatarsal prior to insertion of fixation. This procedure is used to effectively correct an increased HAA.

Examine Figure 23. Note the correction of the 1st IMA achieved with the head procedure, but continued increase in the HAA beyond normal range (approximately 21 degrees here). This can also be appreciated by the abutment of the hallux against the second digit. Following the Akin osteotomy however, the HAA is returned to a normal range (approximately 6 degrees) with a clinical space between the hallux and second digit. In this case, the osteotomy was fixated with a single bicortical screw.

Figure 23.

Pre- and post-operative weight-bearing AP radiographs following an Akin first metatarsal osteotomy (with additional 2nd and 3rd metatarsal osteotomies) in a 39 y/o male patient. Despite previous attempted correction of the HAV deformity with a distal first metatarsal osteotomy, this patient continued to have symptoms and radiographic evidence of an increased HAA. This was corrected surgically with the Akin phalangeal osteotomy with clinical and radiographic correction of the deformity. This was fixated with a single screw.

First Metatarsal-Phalangeal Joint Arthrodesis

A final option for this discussion of correction of the HAV deformity is arthrodesis of the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint. This is not typically a first choice procedure in the treatment of this condition as it is a joint destructive procedure that permanently eliminates motion, but can be used to correct for significant deformity. If arthrodesis is chosen, there is also usually a component of degenerative arthrosis to the joint as diagnosed by radiographic irregular joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis and osteophyte production. Arthrodesis may also be chosen in the setting of an unstable joint, such as a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (Figures 24).

Figure 24.

These figures demonstrate pre- and post-operative weight-bearing AP and lateral radiographs of a 66 y/o male patient who underwent first metatarsal-phalangeal arthrodesis. Pre-operatively in Figure 24a we note a significant deformity with increases in the 1st IMA (approximately 19 degrees here), HAA (approximately 39 degrees here) and MSP (approximately 7 here), but significant return to normal range post-operatively (Figure 24b). This procedure is usually reserved for patients with significant degenerative joint disease or an unstable joint with rheumatoid arthritis, as was the case with this patient. The plate utilized for this procedure is pre-contoured to assist with post-operative joint position. Surgeons attempt to place the joint in approximately 10 degrees of dorsiflexion, 10 degrees of abduction and 0–5 degrees of valgus.

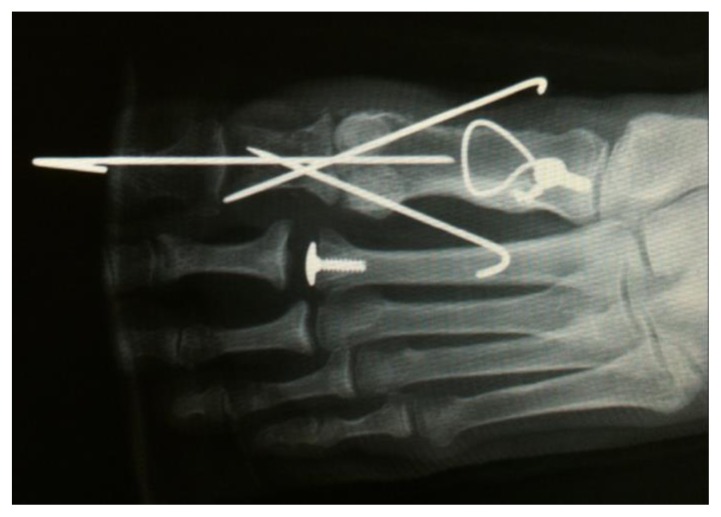

Fixation of an arthrodesis is nearly always with at least two points of fixation, whether with two bicortical screws (Figure 25), two K-wires (Figure 26), or a single screw with a supportive plate (Figures 24).

Figure 25.

This AP post-operative radiograph demonstrates another acceptable way to fixate a first metatarsal-phalangeal joint arthrodesis. Two crossing screws are utilized along two different orientations. Note how the screws cross directly at the arthrodesis joint level.

Figure 26.

This AP post-operative radiograph demonstrates another acceptable way to fixate a first metatarsal-phalangeal joint arthrodesis. Two crossing K-wires are utilized, in addition to an intramedullary K-wire through the hallux and into the first metatarsal. One can appreciate retained hardware in the proximal aspect of the first metatarsal from a previous fracture repair.

Post-operative assessment of this procedure involves a detailed investigation of joint position. An ideal position of the joint involves approximately 10 degrees of phalangeal abduction (or a 10 degree hallux abductus angle), 10 degrees of dorsiflexion, and 0–5 degrees of valgus (not reliably assessed radiographically)[4]. Plates have become a popular means of fixation for this procedure recently as these positions are “built in” to the plate.

TEACHING POINT

The preceding was a basic pictorial review of common procedures utilized by foot and ankle surgeons for correction of the hallux abductovalgus deformity. We attempted to emphasize which specific radiographic findings and measurements lead to procedure selection (Table 1), as well provide as a basic visual understanding of the most commonly performed procedures. It is our hope that radiologists will employ this information to improve their ability to assess postoperative radiographs following foot and ankle reconstructive surgeries.

Table 1.

Overview of radiographic parameters utilized in the interpretation of the hallux abductovalgus deformity and procedures used for their correction.

| Definition | Interpretation | Surgical Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Intermetatarsal Angle (1st IMA) | Resultant angle created between the longitudinal bisections of the first and second metatarsals. |

Normal range: 0–8 degrees Mild increase: 9–11 degrees Moderate increase: 12–15 degrees Severe increase: >15 degrees |

Any translational metatarsal osteotomy will correct the 1st IMA. Mild increases are typically addressed with a first metatarsal “head” procedure (i.e. the Austin/Chevron osteotomy). Moderate increases are typically addressed with a first metatarsal “shaft” procedure (i.e. the Scarf osteotomy). Severe increases are typically addressed with first metatarsal “base” procedure (i.e. the closing base wedge osteotomy or the Lapidus arthrodesis). |

| Hallux Abductus Angle (HAA) | Resultant angle between the longitudinal bisections of the hallux proximal phalanx and first metatarsal. |

Normal range: 0–15 degrees Increases with progressive HAV deformity |

Any procedure which directly decreases the 1st IMA will also indirectly decrease the HAA. Several procedures that will directly decrease the HAA include the proximal phalanx Akin procedures and the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint arthrodesis procedure. |

| Metatarsal-sesamoid position (MSP) | Relationship between the tibial sesamoid and the longitudinal bisection of the first metatarsal |

Normal position: 0–2 Defined on a 7 point scale (see Figure 2) |

Any procedure which directly decreases the 1st IMA will also directly decrease the MSP. |

| Proximal Articular Set Angle (PASA) | Relationship between the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal and the articular cartilage on the first metatarsal head. |

Normal range: 0–8 degrees Normally evaluated intra- operatively as opposed to radiographically. |

The PASA may be directly decreased with the Reverdin first metatarsal head procedures. |

ABBREVIATIONS

- 1st IMA

First intermetatarsal angle

- AP

Anterior-poster

- CBWO

Closing base wedge osteotomy

- DP

Dorsal-plantar

- HAA

Hallux abductus angle

- HAV

Hallux abductovalgus

- K-wire

Kirsner wire

- MSP

Metatarsal-sesamoid position

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanner WH. Foot segmental relationships and bone morphology. In: Christman RA, editor. Foot and Ankle Radiology. First edition. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 272–302. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin DE, Pontious J. Introduction and evaluation of hallux abducto valgus. In: Banks AS, Downey MS, Martin DE, Miller SJ, editors. McGlamry’s Comprehensive Textbook of Foot and Ankle Surgery. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 481–491. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coughlin MJ, Mann RA. Hallux valgus. In: Coughlin MJ, Mann RA, Saltzmann CL, editors. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. Eighth edition. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. pp. 183–362. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahss MH. Disorders of the hallux and the first ray. In: Jahss MH, editor. Disorders of the Foot and Ankle Medical and Surgical Management. Second Edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1991. pp. 943–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy RH, Clapham JC. Observations on hallux valgus: based on a controlled series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1951 Aug;33-B(3):376–91. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.33B3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramdass R, Meyr AJ. The multiplanar effect of first metatarsal osteotomy on sesamoid position. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010 Jan-Feb;49(1):63–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin DW, Leventen EO. A new osteotomy for hallux valgus: a horizontally directed “V” displacement osteotomy of the metatarsal head for hallux valgus and primus varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981 Jun;(157):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KA, Cofield RH, Morrey BF. Chevron osteotomy for hallux valgus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979 Jul-Aug;(142):44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalish SR, Spector JE. The Kalish osteotomy. A review and retrospective analysis of 265 cases. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1994 May;84(5):237–42. doi: 10.7547/87507315-84-5-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isham SA. The Reverdin-Isham procedure for the correction of hallux abducto vaglus. A distal metatarsal osteotomy procedure. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1991 Jan;8(1):81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weil LS. Scarf osteotomy for correction of hallux valgus. Historical perspective, surgical technique, and results. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000 Sep;5(3):559–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nigro JS, Greger GM, Catanzariti AT. Closing base wedge osteotomy. J Foot Surg. 1991 Sep-Oct;30(5):494–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofbauer MH, Grossman JP. The Lapidus procedure. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1996 Jul;13(3):485–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springer KR. The role of the akin osteotomy in the surgical management of hallux abducto valgus. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1989 Jan;6(1):115–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]