Abstract

Delayed myocardial enhancement MRI is a highly valuable but non-specific imaging technique that is ancillary in the diagnosis of a variety of diseases including myocardial viability, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and other infiltrative myocardial processes. The lack of specificity stems from the wide variety of differential diagnoses that may present with overlapping patterns of delayed enhancement. Many of these differential diagnoses have been presented and discussed in this article.

Keywords: Delayed enhancement, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, MRI

REVIEW

Introduction

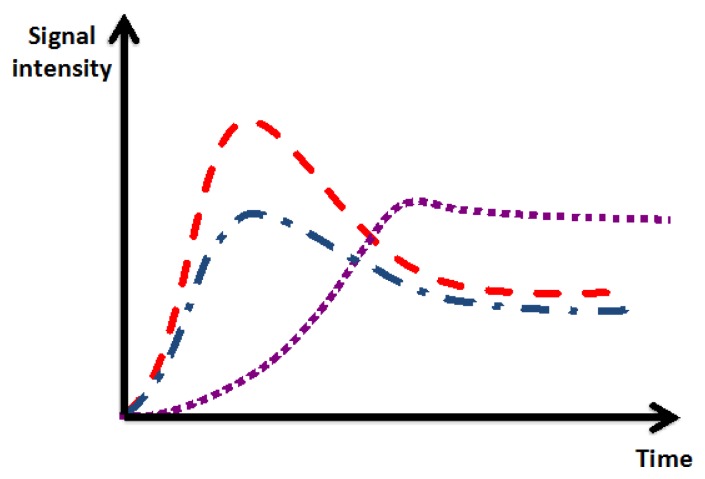

There is a different pattern of early and delayed contrast accumulation in normal and injured myocardial tissue, which is exploited for myocardial perfusion imaging and delayed imaging for the diagnosis of myocardial scar. Ischemic myocardium typically shows delayed time to peak enhancement and lower maximal peak enhancement compared to normal myocardium. Myocardial scar demonstrates increased accumulation of contrast agent in combination with delayed washout over time, which manifests as abnormal myocardial contrast enhancement on delayed imaging [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Contrast kinetics of normal myocardial contrast enhancement (red), ischemic myocardial enhancement (blue), and scarred/fibrotic myocardium (purple). Compared to normal myocardium, ischemic and scarred myocardium demonstrate lower peak and delayed time to peak enhancement. Compared to normal myocardium, myocardial scar demonstrates increased accumulation and delayed washout of contrast over time.

Delayed myocardial enhancement MR imaging is currently used for the diagnosis of myocardial involvement in a variety of cardiac and non-cardiac disorders. Late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was introduced in 1989 [1] for the identification of infarcted myocardial tissue. The technique was described in more detail in 1993 [2] and since became a routine sequence in cardiac MR imaging.

The clinical use of delayed myocardial enhancement MR imaging is most commonly performed for evaluation of a myocardium at risk and for determination of the treatment options. In cases of ischemic cardiomyopathy, as in other cases, it is used to evaluate the presence of a scar. An ischemic myocardium without a scar is salvable by reperfusion therapy. A magnetic resonance water sequence imaging (T2) shows accumulation of extra-cellular fluid in a reversible injured myocardium; however, in an irreversible tissue with fibrosis T2 is negative. Delayed contrast enhanced MRI with a Gadolinium based agent may differentiate between acute and chronic myocardial injury, a sequence that helps the decision-making cardiologist to determine the treatment options and to assess the risk stratification [3].

Technique

A number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of a segmented inversion recovery fast gradient echo sequence for differentiating injured from normal myocardium with a very high signal intensity difference between diseased and normal myocardial tissue [4,5]. The images are typically acquired 10 to 25 minutes following the administration of gadolinium-based contrast agent. The underlying concept of this technique is based on the delayed washout of contrast agent from an area of injured myocardium compared to the rapid washout of the contrast agent from normal myocardium. An inversion recovery signal is applied to “null” the signal of normal myocardium in order to maximize the contrast between affected and normal myocardium [6]. The data acquisition time is usually variable and ranges from approximately 140 – 300 ms depending on the patient’s heart rate. The images are typically acquired during mid-diastole when the heart is relatively motionless. Immediately after the onset of the R wave trigger of the recorded EKG, there is a short delay before the application of the 180 degrees inversion pulse. Following this inversion pulse, there is second delay period, which varies, based on the time post contrast administration for optimal nulling of the signal of normal myocardium [6].

This strategy is most effective in cases when regional differences exist in gadolinium retention, such as in infarcted tissue. This method is less effective in diseases that affect the entire myocardium without regional variation such as amyloidosis. In amyloidosis the entire myocardium tends to be involved in a circumferential manner and the contrast kinetics are similarly altered; the deposition of the abnormal protein typically occurs in a circumferential manner starting in the endocardium and extending through the myocardium in a transmural fashion. Therefore, choosing the optimal T1 time for the inversion recovery pulse is difficult. In cardiac amyloidosis the gadolinium is typically extracted faster from normal myocardial tissue compared to the blood pool. Therefore the optimal inversion time to null the signal of the myocardium should be shorter than in the typical case of myocardial infarction.

Recent developments such as the Phase Sensitive Inversion Recovery (PSIR) sequence facilitate the parameter setting for delayed enhancement imaging and make it less dependent on the precise selection of the inversion time for myocardial signal nulling. The sequence removes the background phase while preserving the signal of the desired magnetization during inversion recovery [7].

Types of delayed enhancement

Delayed enhancement can typically be seen in post-ischemic myocardial infarction (scar). Ischemic infarction typically involves the subendocardial layer due to its distance from the coronary arteries located in the epicardium. If the delayed enhancement involves myocardial layers other than the subendocardium (i.e. midwall or epicardial), different nonischemic myocardial diseases have to be considered. The pattern of the enhancement is helpful for the differential diagnosis and distinguishing an ischemic etiology from non-ischemic causes [8,9]. The most common disease entities that may cause delayed enhancement are summarized in table 1 according to the myocardial layer that the enhancement most likely involves. It needs to be emphasized, however, that the enhancement pattern is not always specific for a particular disease. Therefore the radiological diagnosis should always involve clinical and other ancillary findings.

Table 1.

Delayed enhancement patterns in cardiac MRI.

| Subendocardial |

|

| Global Endocardial |

|

| Mid-Wall |

|

| Subepicardial |

|

| Transmural |

|

Ischemic cardiomyopathy

In the setting of regional myocardial dysfunction caused by ischemic cardiomyopathy, the amount of myocardial tissue exhibiting delayed enhancement is inversely proportional to the likelihood of recovery of systolic thickening that occurs after coronary artery revascularization [10]. Delayed enhancement identifies infarction or fibrotic tissue, while absence of enhancement indicates viable myocardium likely to improve following revascularization [11].

The pattern of the delayed enhancement will reflect the vascular distribution of the affected vascular territory. The location of delayed enhancement within the myocardium will show either subendocardial or transmural enhancement [12,13] [figures 2 – 4].

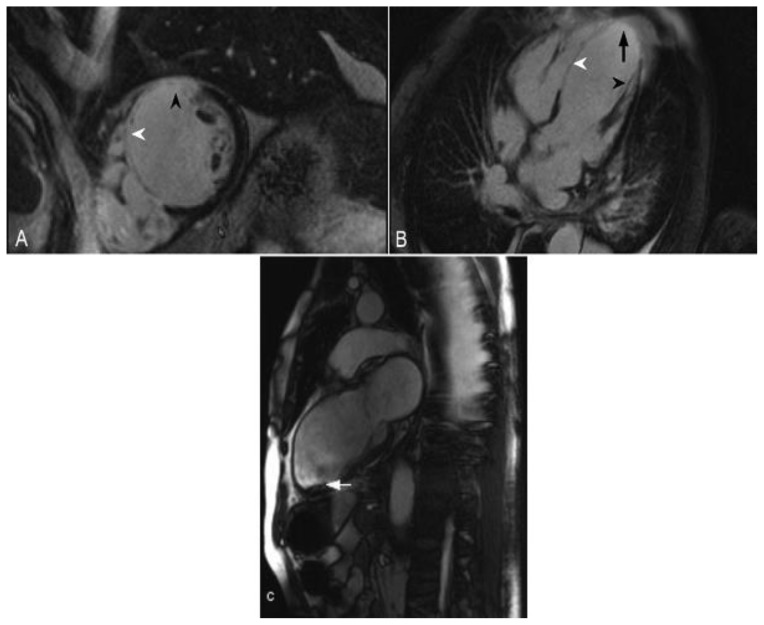

Figure 2.

68-year-old male with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy and an episode of cardiogenic shock. The echocardiography demonstrated a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 25%. Delayed enhancement imaging was performed utilizing an SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. (A) Short axis view demonstrates transmural delayed enhancement of the septum (white arrowhead) and the anterior wall (black arrowhead). (B) Four-chamber view demonstrates transmural delayed enhancement of the septum (white arrowhead) and the apex (arrow). There is also delayed enhancement in the papillary muscle (black arrowhead). (C) Two-chamber view obtained from a cine- SSFP sequence demonstrates thinning of the anterior wall and the apex post infarct. In addition there is aneurysmal dilatation of the apex and a thrombus adjacent to the apicoinferior wall (arrow). These are findings in the vascular territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

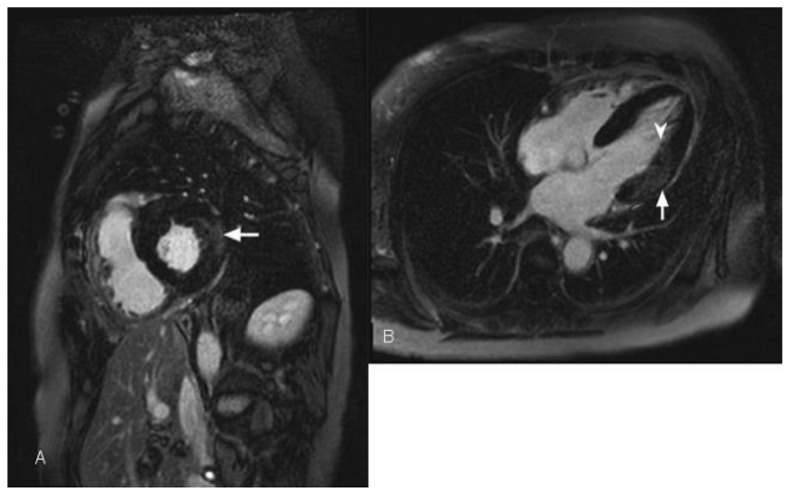

Figure 3.

34 year-old female who underwent coronary angiography at an outside facility, which demonstrated occlusion of the left circumflex coronary artery. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated moderately reduced global left ventricular ejection fraction of 40%. Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement utilizing an SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. Short axis view demonstrates an area of subendocardial delayed enhancement in the inferolateral wall (arrow) corresponding to the vascular territory of the left circumflex coronary artery. Finding represents small post-ischemic subendocardial scar.

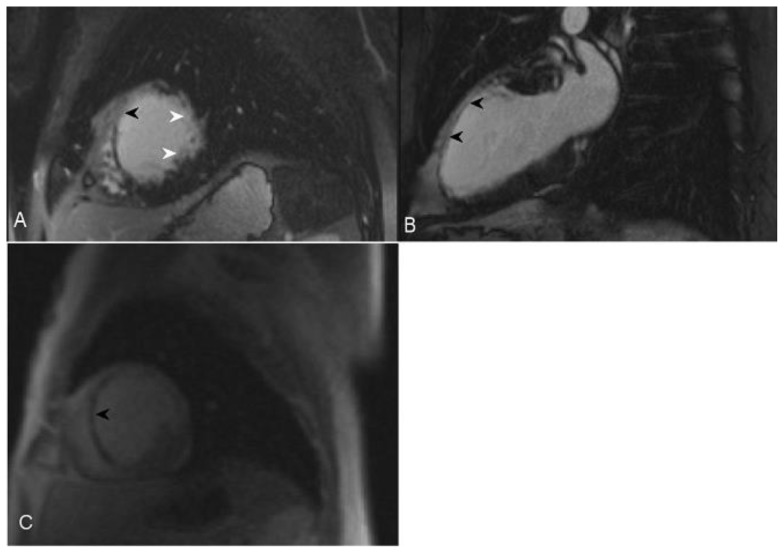

Figure 4.

67-year-old female with history of fixed perfusion defect on Sestamibi SPECT (nuclear) imaging at stress. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated global hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 49%. Delayed enhancement cardiac MRI using an SSFP sequence 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent was performed. (A) Short axis view demonstrates transmural-delayed enhancement of the anterolateral septum (black arrowhead) corresponding to the left anterior descending coronary vascular territory. There is transmural-delayed enhancement of the lateral wall (white arrowheads) corresponding to the left circumflex coronary vascular territory. (B) Two-chamber view demonstrates transmural delayed enhancement of the anterior wall (black arrowheads) corresponding to the left anterior descending coronary vascular territory. (C) Stress perfusion imaging in short-axis orientation demonstrates hypoperfusion of the septum (black arrowhead). The septum, anterior wall, and the lateral wall are thinned, representing scar in the left anterior descending and left circumflex vascular territory. Only the inferolateral segment is viable demonstrating normal thickness and lack of delayed enhancement.

Non-Ischemic Causes

Specific Cardiomyopathy

The distribution pattern of delayed enhancement in different entities that causes cardiomyopathy is typically different from the subendocardial delayed enhancement following a coronary territory found in myocardial infarction. The affected areas may include papillary muscles [figure 5] (sarcoid), the mid-myocardium (Anderson-Fabry disease [figure 6], myocarditis, Becker muscular dystrophy) and the global sub-endocardium (systemic sclerosis, Loeffler’s endocarditis, amyloid, Churg-Strauss). Delayed myocardial enhancement can be observed in Glycogen storage disease [14], although a rare finding [15].

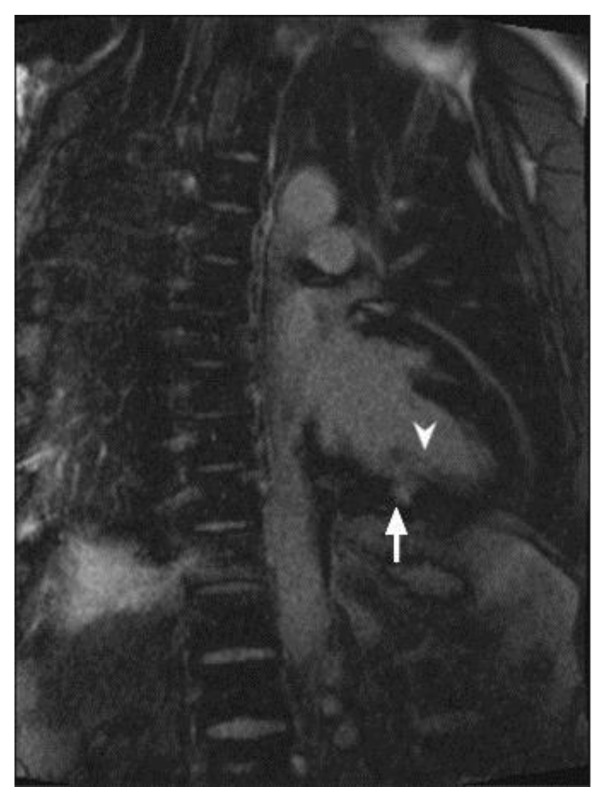

Figure 5.

47-year-old male with sarcoidosis. Cardiac delayed enhancement MRI was performed using an SSFP sequence 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. The two-chamber view demonstrates delayed enhancement of a part of the posterior papillary muscle in the left ventricle (arrowhead). There is an additional focus of near transmural delayed enhancement in the mid inferior wall (arrow).

Figure 6.

56-year-old female with a history of Anderson-Fabry disease. Clinical examination showed multiple angiokeratomas and hypertension. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed and demonstrated left ventricular global circumferential hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with slight elevation of the left ventricular ejection fraction. Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement using an SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. (A) Short-axis view demonstrates mid wall and epicardial delayed enhancement of lateral wall in the mid segment of the heart (arrow). (B) The Four-chamber view demonstrates left ventricular hypertrophy and lateral wall delayed enhancement, which is mainly seen in the mid wall (arrow). In a small portion of the mid heart the enhancement is transmural (arrowhead).

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic disease characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas in the involved organ system. Systemic sarcoidosis affects the respiratory system or mediastinal lymph nodes in more than 90% of cases, but any organ system can be involved. Cardiac involvement is common and significantly alters the patient’s prognosis. Delayed enhanced MRI is considered a sensitive marker of cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis [16]. Cardiac involvement generates symptoms in only 5% of patients with cardiac involvement and has been shown to be present as noncaseating granulomatous infiltration of the myocardium at autopsy in 20–50% of patients [17]. In the advanced postinflammatory stage, delayed enhancement is seen, reflecting replacement fibrosis with higher interstitial concentration of contrast material. This reflects a nonspecific scar that may be associated with myocardial thinning and segmental contraction abnormalities. The delayed enhancement pattern is usually patchy or demonstrates longitudinal striae in the mid wall and/or subepicardium [18,19,20] [figure 7]. This pattern is more commonly observed in the basal septum or left ventricular wall [9]. In the presence of myocardial scar or granuloma the observed delayed enhancement is often patchy or nodular appearance [20,21].

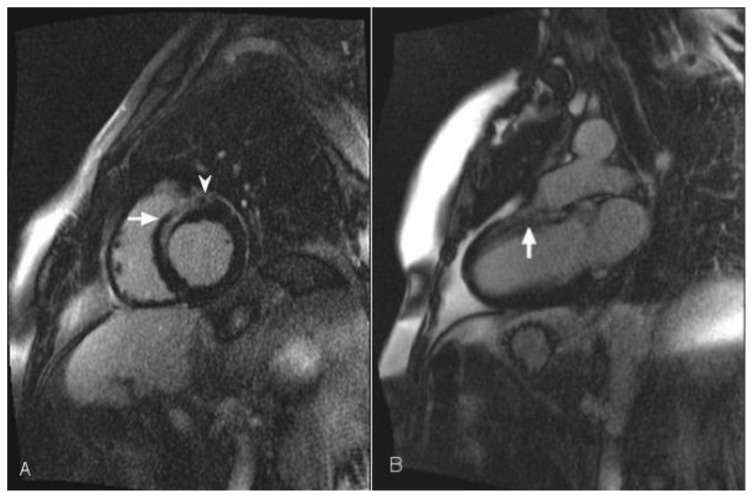

Figure 7.

54-year-old female with sarcoidosis. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated global left ventricular hypokinesis. Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement using an SSFP sequence 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. (A) Short-axis view demonstrates delayed enhancement in the anteroseptal mid wall (arrow) and epicardium (arrowhead). (B) The two-chamber view demonstrates delayed enhancement in the anterior mid wall of the heart (arrow).

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is characterized by the build up of a substance known as amyloid in parenchymal organs and soft tissues. Amyloid is formed from the breakdown of normal or abnormal proteins. The amyloid that is derived from these breakdown products accumulates between the cells of one or more of the body’s organ systems and may interfere with organ function. Cardiac involvement is frequent in systemic amyloidosis of immunoglobulin light chain and transthyretin types and is a major determinant of treatment options and prognosis [22]. Accumulation of these various proteins in the insoluble fibrillar amyloid conformation occurs principally in the myocardial interstitium, leading to diastolic dysfunction and eventually to restrictive cardiomyopathy [23,24,25]. In cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may show a characteristic pattern of global subendocardial late enhancement coupled with abnormal myocardial and blood-pool gadolinium kinetics [25] [figure 8]. In cardiac amyloid disease, the deposition of the abnormal protein typically occurs in a circumferential manner starting in the endocardium and then extending to the myocardium in a transmural fashion. The null point of the myocardium is typically reached before the blood pool is nulled (T1 of the myocardium is shorter than that of the blood), therefore the inversion time (TI) should be adjusted accordingly [7].

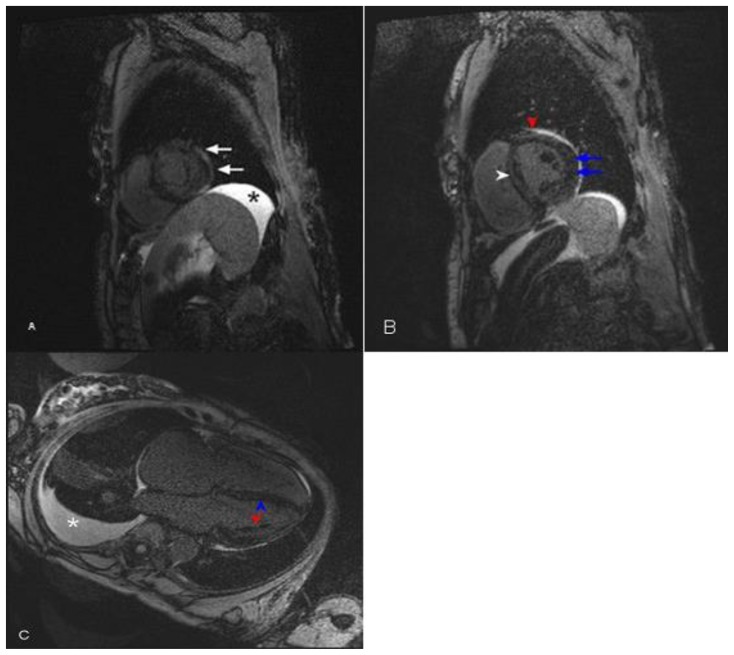

Figure 8.

77-year-old with history of amyloidosis presented with restrictive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, global hypokinesis, and reduced ejection fraction on echocardiography. Delayed enhancement cardiac MRI was performed using an SSFP sequence 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent. (A) Short axis view near the apex demonstrates global patchy diffuse mid-wall delayed enhancement. The arrows point to the delayed enhancement in the lateral wall. Ascites is present (asterisk). (B) Short axis view in the mid heart demonstrates global mid-wall delayed enhancement. The blue arrows point to the delayed enhancement in the lateral wall. The red arrowhead points to the delayed enhancement in the anterior wall. The white arrowhead points to the delayed enhancement in the septum. There is minimal pericardial effusion as indicated by bright signal intensity. (C) Four-chamber demonstrates global mid-wall delayed enhancement. The blue arrowhead points to the delayed enhancement in the septum. The red arrowhead points to the delayed enhancement in the lateral wall. Ascites is present (asterisk).

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

HOCM is a genetic myocardial disorder with an autosomal dominant transmission. It has a prevalence of 1:500 and may lead to lethal arrhythmias in younger adults. It is characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy, which most prominently affects the septum with a diastolic thickness exceeding 15 mm. The septal thickening leads to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in 25% of cases often accompanied by a systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve complex. Delayed enhancement is commonly intramural with a linear and patchy pattern often observed in the interventricular septum [9,26,27] [figure 9].

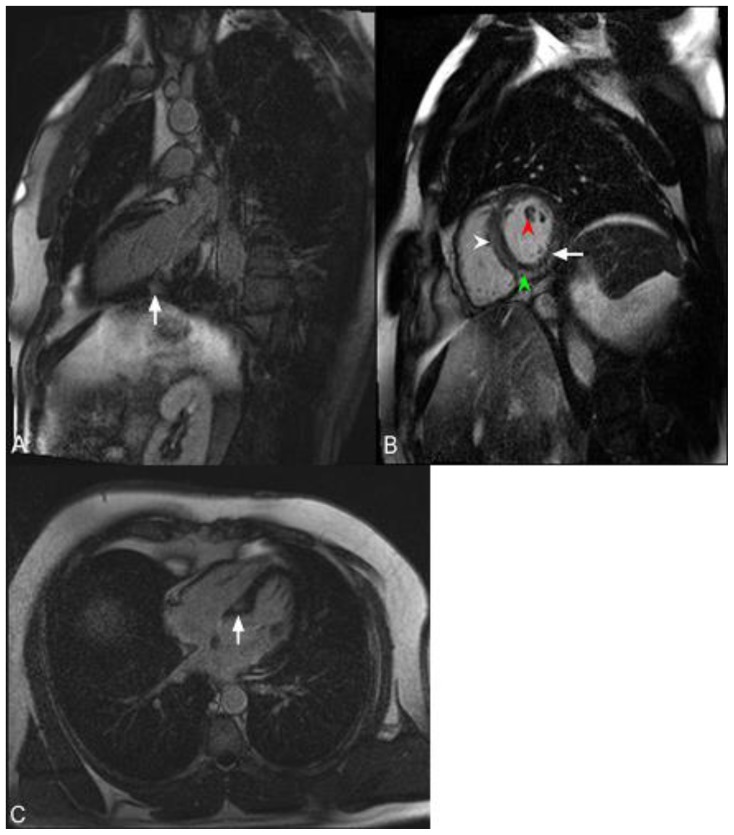

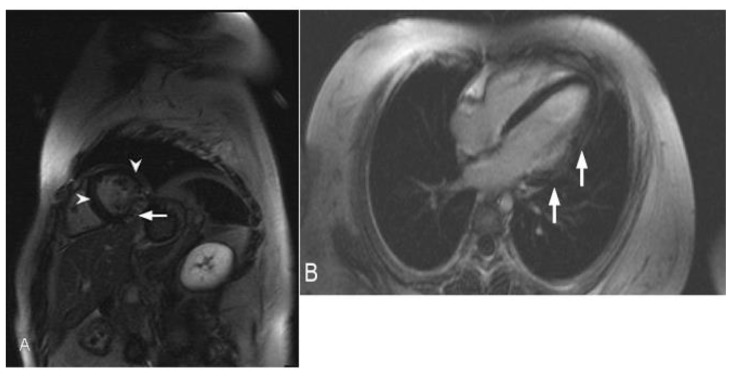

Figure 9.

46-year-old male with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (HOCM). Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement at the SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Multihance and the PSIR pulse. (A) The two-chamber view demonstrates areas of mid-wall delayed enhancement in the inferior wall (arrow). (B) The short axis view demonstrates mid-wall delayed enhancement in the septum (white arrowhead), in the inferior wall (green arrowhead), and in the inferolateral segment of the myocardium (arrow). Delayed enhancement is seen in the papillary muscle (red arrowhead). (C) The Four-chamber view demonstrates mid-wall delayed enhancement in the septum (white arrow).

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is a myoproliferative disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia that is associated with damage to multiple organs.

This is a form of myocarditis with eosinophilic infiltration of the myocardium (Loeffler’s endomyocarditis). This form of myocardial disease has three stages: acute necrotic; thrombotic-necrotic; late fibrotic. Detection during the acute phase is often difficult, as the patient may not present with specific cardiac symptoms; electrocardiography (EKG) or echocardiography may be unremarkable. Therefore, delayed enhancement cardiac MRI is a valuable non-invasive diagnostic tool for the demonstration of myocardial fibrosis and subendocardial delayed enhancement [9,28] [figures 10, 11].

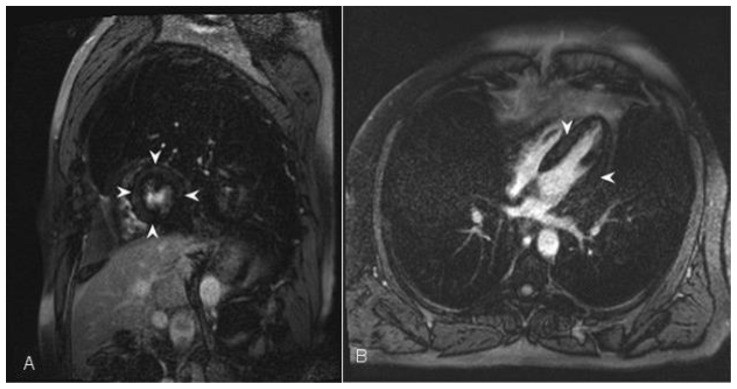

Figure 10.

48-year-old male with hypereosinophilia, factor V leiden deficiency and Churg-Strauss vasculitis. Thoracic echocardiography demonstrated left ventricular hypokinesis with decreased left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volume. Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement using an SSFP sequence 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Gd-based contrast agent (A) The short axis view demonstrates global left ventricular subendocardial and mid-wall delayed enhancement (arrowhead). (B) The four-chamber view demonstrates global left ventricular subendocardial and mid-wall delayed enhancement (arrowheads).

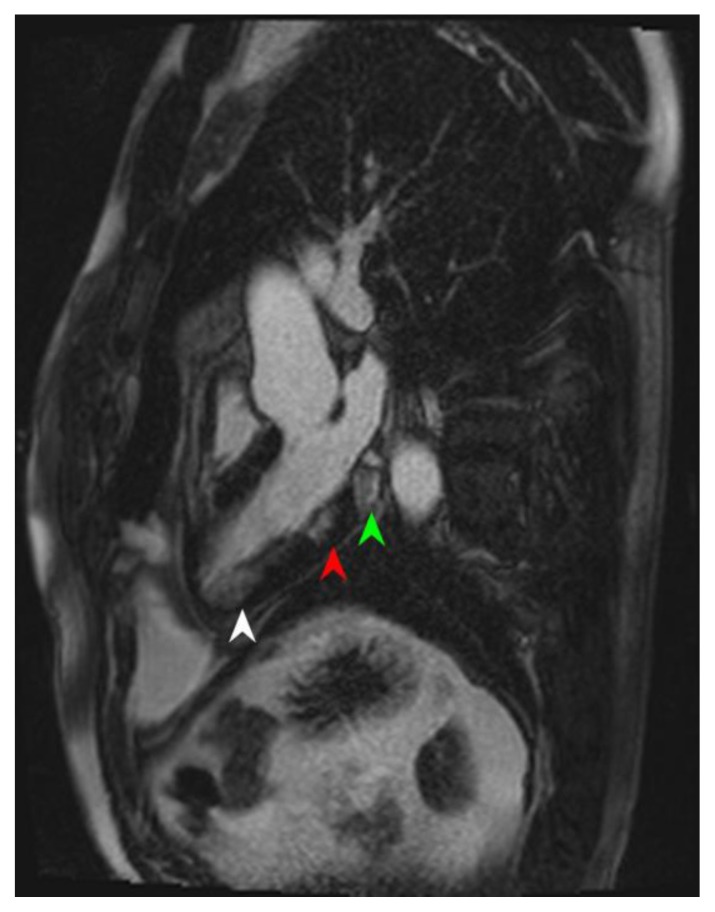

Figure 11.

39-year-old male with atopy, hypereosinophilia syndrome. Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement at the SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Multihance and the PSIR pulse. The Three-chamber view of the heart demonstrates patchy inferior wall delayed enhancement; global endocardial near the apex (white arrowhead), in the mid segment of the inferior wall (red arrowhead), and near the base (green arrowhead).

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy can be idiopathic or secondary to other disease entities including myocarditis, Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophies, and pregnancy. It is defined as a left ventricular end-diastolic diameter of more than 55mm. Delayed enhancement typically demonstrates a patchy longitudinal mid-wall pattern without subendocardial involvement [9,29,30].

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

Findings may include right ventricular dilatation, regional wall thinning, hypertrophy, and aneurysms. ARVC can lead to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Fatty and fibro-fatty variants of ARVC exist. On delayed enhancement the fatty variant is typically identified by myocardial fatty infiltration without ventricular wall thinning, while the fibro-fatty variant demonstrates right ventricular wall thinning. The sub-tricuspid area, infundibulum, and right ventricular apex are most commonly identified as abnormal on MRI [9,31,32].

Muscular Dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy is a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders characterized by progressive wasting and weakness of the skeletal muscles. There are 4 groups of skeletal muscle disease most commonly associated with cardiac complications: (1) dystrophin-associated diseases such as Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, (2) Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, (3) limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, and (4) myotonic dystrophy. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy are X-linked disorders affecting the synthesis of dystrophin, a large, sarcolemmal protein that is absent in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and reduced in amount or abnormal in size in Becker muscular dystrophy patients. In several forms of muscular dystrophy, cardiac dysfunction occurs, and cardiac disease may even be the predominant manifestation of the underlying genetic myopathy.

Common findings on delayed enhancement images involve the mid-wall and subepicardium due to myocardial fibrosis. The imaging findings may be global or regional, affecting the inferolateral, anterolateral, anterior, and/or septal walls [33,34] [figure 12].

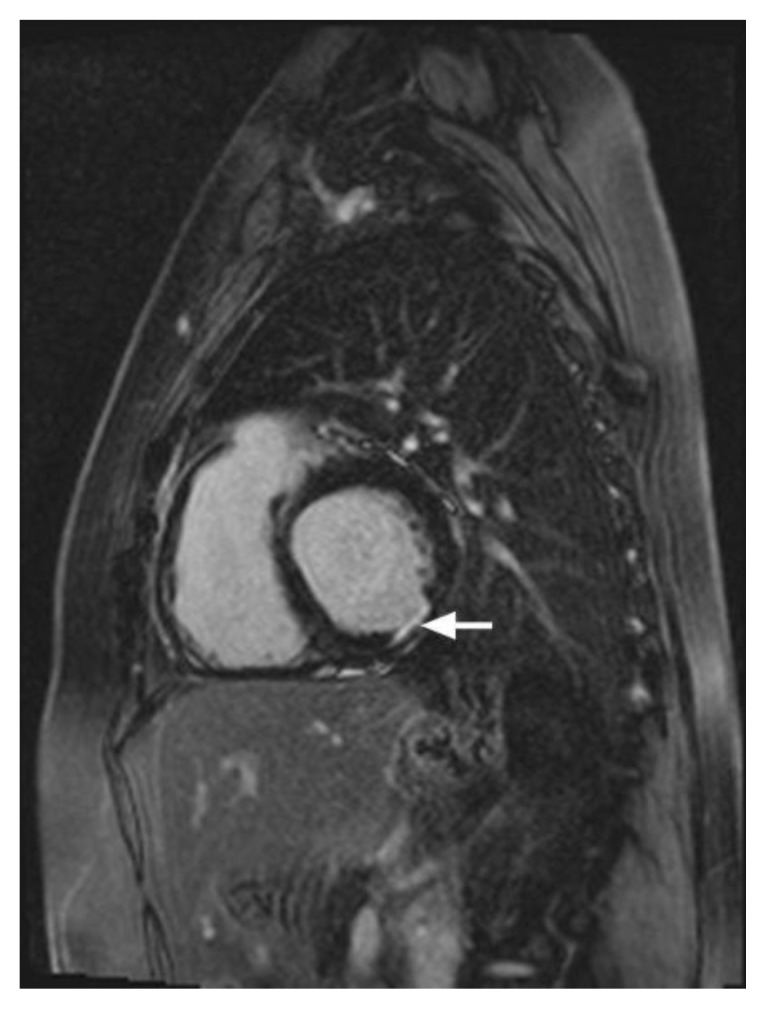

Figure 12.

12-year-old male with Duchenne muscular dystrophy Cardiac MRI was performed with delayed enhancement at the SSFP sequence, 10 minutes following the administration of 20 ml of Multihance and the PSIR pulse. (A) The short-axis view demonstrates transmural delayed enhancement of the lateral wall (arrow) and mid-wall enhancement of the anterior wall and the septum (arrowheads). (B) The Four-chamber view demonstrates patchy transmural delayed enhancement in the lateral wall at base to apex (arrows).

Conclusion

There are two main entities for delayed myocardial enhancement: ischemic and non-ischemic. Ischemic cardiomyopathy typically presents with involvement of the subendocardium, while non-ischemic causes do not necessarily involve the subendocardium. The non-ischemic category includes a number of differential diagnoses for delayed enhancement, many of which demonstrate overlapping imaging characteristics.

TEACHING POINT

Myocardial delayed enhancement is a highly valuable tool for the diagnosis of fibrosis, scar or nonviable myocardium, whether the full thickness of the myocardial segment is involved or just one of its layers. The finding is nonspecific and the inclusion of clinical information is essential in the diagnostic decision process. Often the definition of type, pattern and extent of delayed enhancement is useful for disease prognosis and therapeutic management decision.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis table for delayed myocardial enhancement in cardiac MRI.

| Diagnosis | Clinical manifestation | Pattern of enhancement |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | Fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitations, pulmonary edema, and leg swelling | Subendocardial and/or transmural |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome | Symptoms of heart failure, intracardiac thrombus, myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, and rarely pericarditis | Subendocardial and/or global endocardial |

| Amyloidosis | Symptoms indicative of restrictive cardiomyopathy (cardiac amyloidosis is the most common cause of restrictive cardiomyopathy) | Global endocardial |

| Systemic sclerosis | Cardiac manifestations can affect all structures of the heart, and may result in pericardial effusion, arrhythmias, conduction system defects, valvular impairment, myocardial ischemia, myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure | Global endocardial |

| Churg-Strauss Syndrome | Symptoms consistent with cardiomyopathy as a consequence of vasculitis- related ischemia affecting small myocardial vessels and coronary arteries, or from eosinophilic or granulomatous myocardial infiltration | Global endocardial |

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy | Ventricular enlargement and systolic dysfunction. Disease progression may lead to mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation and eventually heart failure | Mid wall |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy | Thickening of the myocardium, most commonly affecting the septum. This may lead to left ventricular outflow obstruction and eventually heart failure | Mid wall |

| Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy | Myocardial damage likely related to mechanical stress imposed on a metabolically and structurally abnormal myocardium. Fibrosis commonly occurs in the inferolateral wall | Mid wall and/or subepicardial, typically inferolateral wall |

| Becker’s Muscular Dystrophy | Myocardial damage has been postulated to result from mechanical stress imposed on a metabolically and structurally abnormal myocardium. Fibrosis commonly occurs in the inferolateral wall. | Mid wall, typically inferolateral wall |

| Myocarditis | Cardiac manifestation may result in chest pain, fever, sweats, chills, dyspnea, palpitations, syncope, heart failure, and sudden death | Mid wall and/or subepicardial |

| Anderson-Fabry Disease | Clinical disease manifestations include left-ventricular myocardial hypertrophy, valvular thickening, and ectasia of the ascending aorta and conduction abnormalities. Myocardial fibrosis is typically an end-stage manifestation. | Mid wall |

| Sarcoidosis | Symptoms of cardiac sarcoidosis may include congestive heart failure, conduction abnormalities, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death. In its early stages, sarcoid is an active inflammatory disorder that may cause myocardial edema, which may progress to fibrosis | Mid wall and/or subepicardial |

ABBREVIATIONS

- ARVC

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

- EKG

Electrocardiography

- HOCM

Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- PSIR

Phase sensitive Image Recovery

- SPECT

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- SSFP

Steady State Free Procession

- TI

Time of Inversion

REFERENCES

- 1.Saeed M, Wagner S, Wendland MF, Derugin N, Finkbeiner WE, Higgins CB. Occlusive and reperfused myocardial infarcts: differentiation with Mn-DPDP-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172:59–64. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.1.2500678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dulce MC, Duerinckx AJ, Hartiala J, Caputo GR, O’Sullivan M, Cheitlin MD, Higgins CB. MR imaging of the myocardium using nonionic contrast medium: signal-intensity changes in patients with subacute myocardial infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993 May;160(5):963–70. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.5.8470611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Aty H. Myocardial Edema Imaging of the Area at Risk in Acute Myocardial Infarction: Seeing Through Water. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009 Jul;2(7):832–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, Bundy J, Finn JP, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999 Nov 9;100(19):1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, Chen EL, Parker MA, Simonetti O, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Judd RM. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 16;343(20):1445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim RJ, Shah DJ, Judd RM. How we perform delayed enhancement imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2003 Jul;5(3):505–14. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesquita D1, Nobre C, Thomas B, Jalles Tavares N. Cardiac amyloidosis: diagnosis using delayed enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance imaging sequences. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013 Nov;32(11):941–5. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunold P, Schlosser T, Vogt FM, Eggebrecht H, Schmermund A, Bruder O, Schüler WO, Barkhausen J. Myocardial late enhancement in contrast-enhanced cardiac MRI: distinction between infarction scar and non-infarction-related disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 May;184(5):1420–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim RP, Srichai MB, Lee VS. Non-ischemic causes of delayed myocardial hyperenhancement on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007 Jun;188(6):1675–81. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi KM, Kim RJ, Gubernikoff G, Vargas JD, Parker M, Judd RM. Transmural extent of acute myocardial infarction predicts long-term improvement in contractile function. Circulation. 2001;104:1101–1107. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.096798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandapaka S, D’Agostino R, Jr, Hundley WG. Does late gadolinium enhancement predict cardiac events in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy? Circulation. 2006 Jun 13;113(23):2676–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.631432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel-Claussen J1, Rochitte CE, Wu KC, Kamel IR, Foo TK, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Delayed enhancement MR imaging: utility in myocardial assessment. Radiographics. 2006 May-Jun;26(3):795–810. doi: 10.1148/rg.263055047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betts A, Dolewski DA, York G. Delayed Myocardial Enhancement. J Am Osteopath Coll Radiol. 2013;2(2):21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiocchi F, Ricci C, Ligabue G, Reggianini L, Modena MG, Cenacchi G, Torricelli P. Cardiac delayed enhancement distribution in extralysosomial glycogen storage disease. Clin Imaging. 2008 Nov-Dec;32(6):474–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker PC, Pasquali SK, Darty S, Ing RJ, Li JS, Kim RJ, DeArmey S, Kishnani PS, Campbell MJ. Use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate cardiac structure, function and fibrosis in children with infantile Pompe disease on enzyme replacement therapy. Mol Genet Metab. 2010 Dec;101(4):332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, Kubo S, Kanao S, Saga T, Harada M, Ohba M, Hosokawa R, Kimura T, Kita T, Togashi K. Effectiveness of delayed enhanced MRI for identification of cardiac sarcoidosis: comparison with radionuclide imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Jul;185(1):110–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, Fruie T, Shigematsu N, Izumi T, Homma AH, Mikami R, Hongo O, Hiraga Y, Yamamoto M. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:455–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serra JJ, Monte GU, Mello ES, Coral GP, Avila LF, Parga JR, Ramires JA, Rochitte CE. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Cardiac sarcoidosis evaluated by delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003 May 27;107(20):e188–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062400.74155.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vignaux O, Dhote R, Duboc D, Blanche P, Dusser D, Weber S, Legmann P. Clinical significance of myocardial magnetic resonance abnormalities in patients with sarcoidosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Chest. 2002 Dec;122(6):1895–901. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vignaux O. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Spectrum of MRI Features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Jan;184(1):249–54. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings KW1, Bhalla S, Javidan-Nejad C, Bierhals AJ, Gutierrez FR, Woodard PK. A pattern-based approach to assessment of delayed enhancement in nonischemic cardiomyopathy at MR imaging. Radiographics. 2009 Jan-Feb;29(1):89–103. doi: 10.1148/rg.291085052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68:220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbustini E, Gavazzi A, Merlini G. Fibril-forming proteins: the amyloidosis: new hopes for a disease that cardiologists must know. Ital Heart J. 2002;3:590–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nihoyannopoulos P. Amyloid heart disease. Current Opin Cardiol. 1987;2:371–376. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maceira AM, Joshi J, Prasad SK, Moon JC, Perugini E, Harding I, Sheppard MN, Poole-Wilson PA, Hawkins PN, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2005 Jan 18;111(2):186–93. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152819.97857.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, Bilinska Z, Cecchi F, Charron P, Dubourg O, Kühl U, Maisch B, McKenna WJ, Monserrat L, Pankuweit S, Rapezzi C, Seferovic P, Tavazzi L, Keren A. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society Of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008 Jan;29(2):270–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura RA, Holmes DR., Jr Clinical practice. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar;25:350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tani H, Amano Y, Tachi M, Machida T, Mizuno K, Kumita S. T2-weighted and delayed enhancement MRI of eosinophilic myocarditis: relationship with clinical phases and global cardiac function. Jpn J Radiol. 2012 Dec;30(10):824–31. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCrohon JA, Moon JC, Prasad SK, McKenna WJ, Lorenz CH, Coats AJ, Pennell DJ. Differentiation of heart failure related to dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease using gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2003 Jul 8;108(1):54–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078641.19365.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assomull RG, Prasad SK, Lyne J, Smith G, Burman ED, Khan M, Sheppard MN, Poole-Wilson PA, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Nov 21;48(10):1977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain Aditya, Tandri Harikrishna, Calkins Hugh, Bluemke David A. Role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris SR, Glockner J, Misselt AJ, Syed IS, Araoz PA. Cardiac MR imaging of nonischemic cardiomyopathies. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008 May;16(2):165–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guillaume Melissa D, MD, Phoon Colin KL, MPhil, MD, Chun Anne JL, MD, Srichai Monvadi B., MD Delayed Enhancement Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in a Patient with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35(3):367–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva MC, Meira ZM, Gurgel Giannetti J, da Silva MM, Campos AF, Barbosa Mde M, Starling Filho GM, de Ferreira RA, Zatz M, Rochitte CE. Myocardial delayed enhancement by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with muscular dystrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 May 8;49(18):1874–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]