Abstract

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a fibroinflammatory disorder that can affect virtually every organ system. T helper type 2 responses have been presumed to be pathogenic in this disease and a high proportion of IgG4-RD patients are reported to have longstanding allergies, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and serum IgE elevation. It has therefore been proposed that allergic mechanisms drive IgG4-RD. However, no epidemiological assessment of atopy, peripheral blood eosinophilia, serumIgEconcentrationshas ever been undertaken in IgG4-RD patients. In the present manuscript, we evaluated these parameters in a large cohort of IgG4-RD patients in whom a wide range of organs were affected by disease. Our results demonstrate that the majority of IgG4-RD patients are non-atopic. Nevertheless, a subset of non-atopic subjects exhibit peripheral blood eosinophilia and elevated IgE, suggesting that processes inherent to IgG4-RD itself rather than atopyper se contribute to the eosinophilia and IgE elevation observed in the absence of atopy.

Keywords: Allergy, Atopy, Eosinophilia, IgG4-Related Disease, Th2 response

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a fibroinflammatory disorder characterized by tumefactive lesions in affected organs, elevated serum IgG4 concentrations in the majority of cases, and responsiveness to glucocorticoid treatment. The typical histopathological features of IgG4-RD are a diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with an abundance of IgG4-positive plasma cells, storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and a mild to moderate tissue eosinophilia1.Although the pathogenesis of IgG4-RD remains poorly understood, several studies have suggested a causative role for T helper type 2 (Th2) cells2,3. It has also been reported that a proportion of patients with type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis have longstanding histories of allergies, peripheral blood eosinophilia (PBE), and serum IgE elevation, or manifest atopic symptoms (rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma) during the time that the full IgG4-RD phenotype develops4,5. Moreover, allergic immune responses can be induced by specific Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which promote PBE and the secretion of IgG4 and IgE6. Therefore, it has been proposed that allergic mechanisms drive IgG4-RD in at least a subset of patients4, but no detailed assessment of atopy, PBE, and serum IgE elevation in IgG4-RD patients has ever been undertaken.

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of atopy, PBE, and IgE elevation in a large, single-center cohort of patients with IgG4-RD. Seventy sequential patients with biopsy-proven IgG4-RD presenting to the Massachusetts General Hospital Rheumatology Clinic between May 2011 and June 2013 were included. All subjects signed written, informed consent for the investigations described. Using the definitions of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, we classified the subjects as either atopic or non-atopic7. The subjects’ peripheral blood eosinophils and concentrations of IgE and IgG4 were measured at the time of IgG4-RD diagnosis, before the institution of specific therapies. The subjects’ mean age was 54.7 years (range 24-82), and the male:female ratio was 1.9:1. The subjects’ clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Skin prick tests and specific IgE evaluations were performed in 10 atopic patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients affected by IgG4-RD.

| Atopic patients (n=22) | Non-atopic patients (n=48) | All patients (n=70) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 49.4 (24-78) | 57.1 (28-82) | 54.7 (24-82) |

| Male / Female ratio | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Atopic symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Rhinitis | 16 (73%) | ||

| Conjunctivitis | 5 (23%) | ||

| Asthma | 8 (36%) | ||

| Hives | 3 (13%) | ||

| Oral allergic syndrome | 1 (5%) | ||

| Anaphylaxis | 0 | ||

| Organ involvement, n (%) | |||

| Salivary glands | 13 (59%) | 19 (40%) | 32 (46%) |

| Lacrimal glands | 6 (27%) | 8 (17%) | 14 (20%) |

| Orbit | 4 (18%) | 4 (8%) | 8 (11%) |

| Pachymeninges | 1 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

| Nasopharynx | 4 (18%) | 4 (8%) | 8 (11%) |

| Lymph nodes | 5 (23%) | 7 (15%) | 12 (17%) |

| Thyroid | 1 (5%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Lung | 4 (18%) | 8 (17%) | 12 (17%) |

| Pericardium | 1 (5%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Pancreas | 7 (32%) | 11 (23%) | 18 (26%) |

| Liver | 1 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Biliary tree | 3 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 8 (11%) |

| Retroperitoneum | 1 (5%) | 14 (29%) | 15 (21%) |

| Mesentery | 1 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Kidney | 2 (9%) | 6 (13%) | 8 (11%) |

| Aorta | 4 (18%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (9%) |

| Prostate | 1 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

| Skin | 1 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Laboratory analysis, mean (range) | |||

| Eosinophils (cells/μL) (< 500 cells/ μ L) | 641 (40-1500) | 365 (20-2000) | 463 (20-2000) |

| Serum IgE (IU/mL) (< 100 IU/mL) | 454 (5-1860) | 153 (5-1360) | 262 (5-1860) |

| Serum IgG4 (mg/dL) (< 121 mg/dL) | 742 (11-4780) | 343 (3-2200) | 489 (3-4780) |

The spectrum of organ involvement in atopic and non-atopic individuals was generally similar across the two groups, except for the higher percentage of patients in the non-atopic group who experienced retroperitoneal fibrosis (29% versus 5%).An atopic background was identified in 22 patients (31%), with seasonal or perennial oculo-rhinitis being the most frequently reported symptom. Skin testing and allergen-specific IgE evaluation demonstrated sensitization to multiple antigens including dust mite, mold, grass, ragweed, cat dander, and shellfish.

Elevated serum IgElevels were observed in 35% of the subjects in the overall cohort, with a mean concentration of 523 IU/mL (range 129-1869 IU/mL; normal < 100 IU/mL). Peripheral blood eosinophilia was present in 27% of the overall cohort, with a mean of 1062 cells/μL (range 600-2000 cells/μL; normal <500 cells/μL). The serum IgG4 level was elevated in 43 patients (61%) (mean 705 mg/dL; range 132-4780; normal < 121 mg/dL).

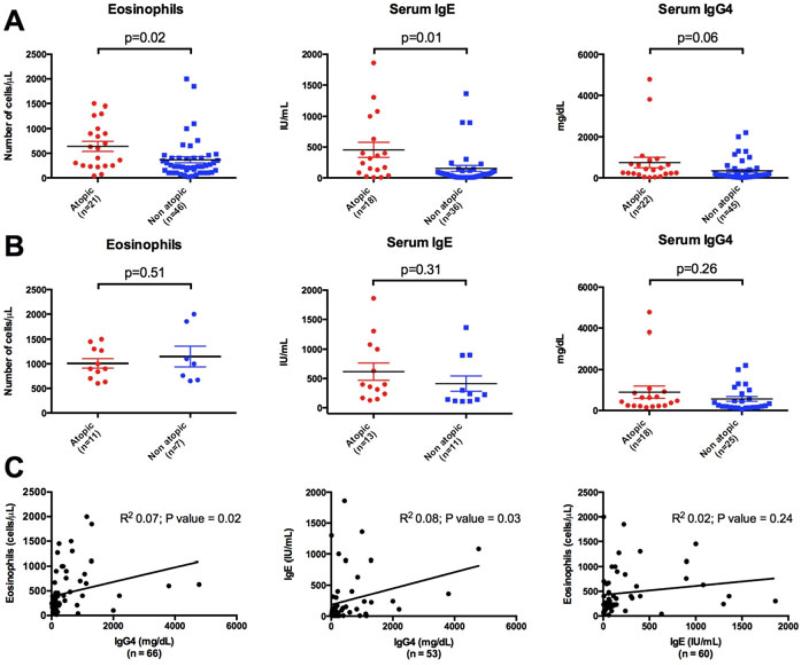

The majority of atopic subjects presented with PBE (52%) or elevated serum IgE levels (62%). Sixty-seven percent of the non-atopic patients had normal concentrations of bothIgE and eosinophils, but 15% of the non-atopic patients had PBE and 24% had elevated serum IgE concentrations. The mean values of serum IgE and eosinophils were higher in atopic patients than in non-atopic subjects(454 mg/dL versus 153 mg/dL [P = 0.01] and 641 versus 365 [P = 0.02], respectively). The mean serum IgG4 concentration was numerically higher in the atopic group (742 mg/dL versus 343 mg/dL; P = 0.06), but this comparison did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Comparison of eosinophil count, serum IgE and IgG4 levels between atopic and non-atopic IgG4-RD patients.

(A) Overall atopic and non-atopic IgG4-RD patients. (B) Atopic and non-atopic IgG4-RD patients presenting with PBE (> 500 cells/ μL), elevated serum IgE (> 100 IU/mL) and IgG4 (> 121 mg/dL) levels. Horizontal bars represent mean frequencies from studied patients ± Standard Error of the Mean. P-values < 0.05 were considered as significant. (C)Comparison of eosinophil count, serum IgE and IgG4 levels by Pearson correlation test. P-values < 0.05 were considered as significant.

There was no statistically significant difference in the eosinophil counts or the serum concentrations of serum IgE and IgG4 between IgG4-RD atopic and non-atopic patients who presented with PBE, elevated IgE, or elevated IgG4 (Figure 1B). Linear regression studies demonstrated a positive correlation between serum IgG4 levels and both serum IgE(correlation coefficient = 0.08; P = 0.03) and eosinophil counts (correlation coefficient = 0.07; P = 0.02),but no correlation was found between eosinophil counts and seurmIgE levels (P = 0.24) (Figure 1C).

To our knowledge, the present work is the first to examine the relationship between atopy and IgG4-RDsystematically and to assess the prevalence of PBE and IgE elevation in IgG4-RD patients. Despite the notion that the prevalence of atopy is high among patients with IgG4-RD, in fact the prevalence of atopyin our cohort was not different from that of the US general population8. Furthermore, the allergenic sensitization profile, when measured by skin prick test or specific IgE quantitation, failed to reveal a common culprit allergen. These data argue against the concept that allergic responses to specific allergens initiate and drive the aberrant immune reaction for patients with IgG4-RD in general. Among patients who presented with either an elevation in IgE or PBE, the mean IgE concentrations and eosinophil counts were similar regardless of whether patients were atopic or non-atopic. These findings support the concept that both elevated IgE concentrations and PBE are related to inherent characteristics of the IgG4-RD immune response itself rather than to an underlying atopic condition.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that the majority of IgG4-RD patients are non-atopic and that the prevalence of atopy in this disease is no higher than that expected in the general population. Our data also imply that the inflammatory milieu of IgG4-RD itself sustains the IgE elevation and PBE observed, regardless of the antigenic trigger(s). These studies suggest that the origin of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells in IgG4-RD and their contributions to the disease process should be considered in a new light.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants AI 064930 and AI 076505 from the NIH to SP

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no relevant conflict of interest

Author Contributions: EDT and MC analyzed the clinicalmaterial,supervised by JHS.HM and VSM conductedlaboratorystudies with guidance from SP.EDT and HM analyzed the data and EDT, SP, and JHS drafted the manuscript.Allauthorsread and approved the finalversion.

References

- 1.Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1104650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka A, Moriyama M, Nakashima H, Miyake K, Hayashida JN, Maehara T, et al. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions contribute to IgG4 production and the initiation of Mikulicz disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:254e63. doi: 10.1002/art.33320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zen Y, Fujii T, Harada K, Kawano M, Yamada K, Takahira M, et al. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions are increased in immunoglobin G4-related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1538–46. doi: 10.1002/hep.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamisawa T, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kubota N. Allergic manifestations in autoimmune pancreatitis. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol. 2009;21:1136–9. doi: 10.1097/meg.0b013e3283297417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriyama M, Tanaka A, Maehara T, Furukawa S, Nakashima H, Nakamura S. T helper subsets in Sjögren's syndrome and IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialoadenitis: A critical review. J. Autoimmun. 2013:S0896–8411(13)00103-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelman FD, Boyce JA, Vercelli D, Rothenberg ME. Key advances in mechanisms of asthma, allergy, and immunology in 2009. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2010;125:312e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy.An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001;56:813–824. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.t01-1-00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppin JA, Jaramillo R, Salo P, Sandler DP, London SJ, Zeldin DC. Questionnaire predictors of atopy in a US population sample: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:544–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]