Abstract

Angiocentric glioma is a rare subtype of neuroepithelial tumor that is associated with a history of epilepsy. We report a case of cystoid angiocentric glioma associated with an area of calcification. This 25 year old male patient presented with tonic clonic spasm. He underwent craniotomy with complete resection of the lesion. Pathologic specimen showed monomorphous bipolar cells with angiocentric growth pattern.

Keywords: Angiocentric glioma, Neuroepithelial tumor, Temporal lobe, Epilepsy, Magnetic resonance imaging

CASE REPORT

Presentation

This 25-year-old male presented to our hospital on February 2014 with a history of multiple seizure episodes within the past year. The seizures, which were tonic-tonic spasms, occurred at nighttime with each episode lasting about 2 minutes. The episodes were not associated with headaches or focal neurological deficits. Routine EEGs showed no abnormalities.

Imaging features

Head Computed Tomography (CT) showed a low density lesion involving the right frontal region. There was also a small area of calcification located anterior to the lesion (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a relatively well defined cystoid lesion that was hypo-intense on T1WI (T1-weighted image) and FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) image, and hyper-intense on T2WI (T2- weighted image) (Fig. 2). There were no diffusion restrictions on DWI (diffusion weighted image) (Fig. 2). There was an intrinsic cortical high signal “rim” surrounding the lesion on T1WI (Fig. 3). Coronal T2WI showed an ovoid lesion (1.7cm×1.3cm×1.0cm) perpendicular to the cerebral ventricle (Fig. 3). No enhancement was observed within the lesion on postcontrast T1WI (Fig. 4).

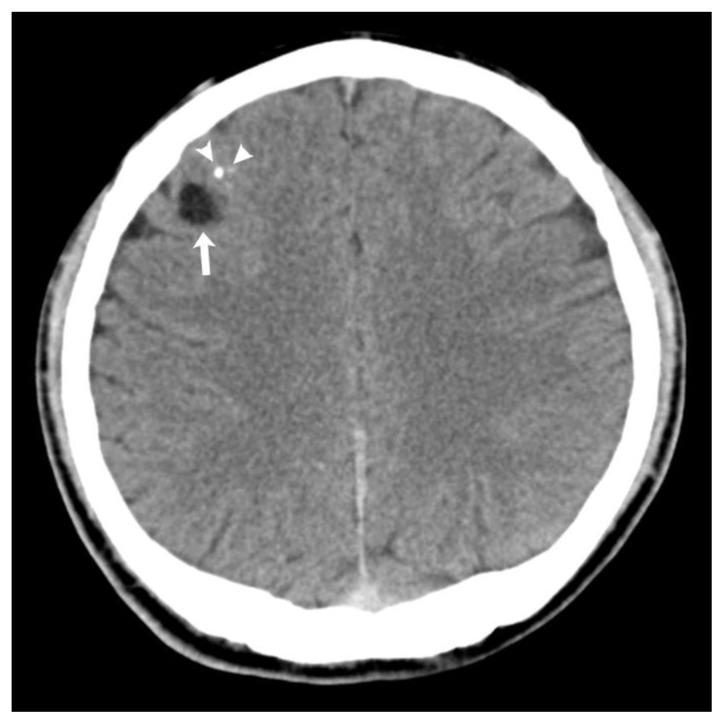

Figure 1.

25-year-old male with angiocentric glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Findings: Noncontrast axial CT scan demonstrates a low density lesion (arrow) involving the right frontal region. There is a small area of calcification (CT value=116 HU) located anterior to the lesion (arrowhead).

Technique: Siemens (SOMATOM Emotion) 16-slice multidetector CT, sequential axial, 270 mAs, 130 kVp, 4.8 mm slice thickness.

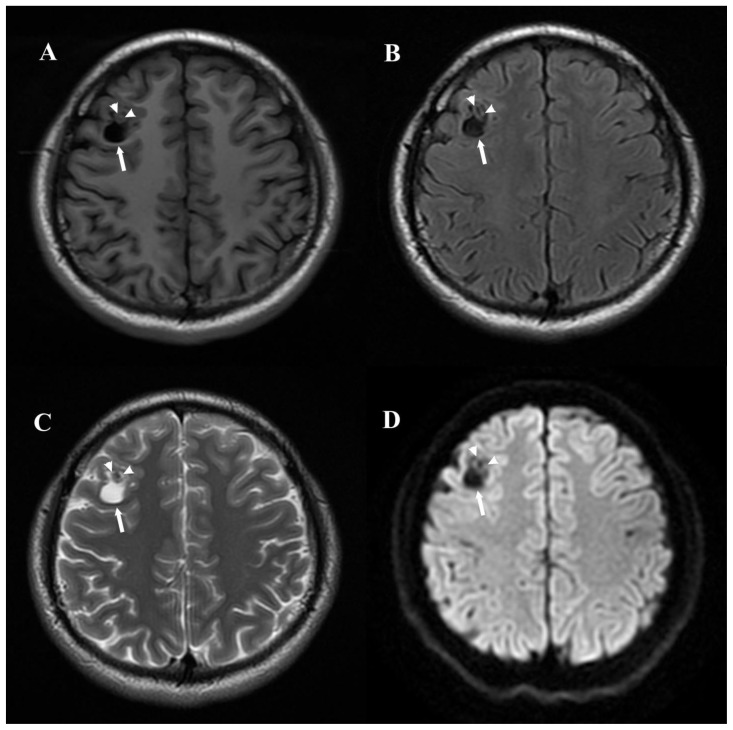

Figure 2.

25-year-old male with angiocentric glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Findings: Axial T1WI (T1-FLAIR) (A), FLAIR (B) and T2WI (C) demonstrate a relatively well defined cystoid lesion (arrow) that is hypo-intense on T1WI and FLAIR image, and hyper-intense on T2WI. There are no diffusion restrictions on DWI (D). The small area of calcification (arrowhead) anterior to the cystoid lesion is isointense on T1WI, hypo-intense on FLAIR image, T2WI and DWI.

Technique: 3.0T Signa HD (GE, USA) MR scanner. 5.0mm slice thickness. T1WI (T1-FLAIR): TR=2580ms, TE=16ms, TI=860ms. FLAIR: TR=9000ms, TE=155ms, TI=2250ms. T2WI: TR=3280ms, TE=108ms. DWI: b-value =0 and 1000 s/mm2, TR=5300ms, TE=75ms.

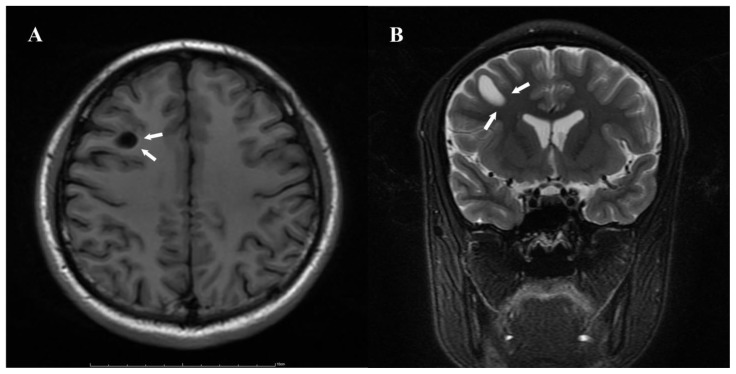

Figure 3.

25-year-old male with angiocentric glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Findings: A. Axial T1WI (T1-FLAIR) demonstrates a hyper-intense “rim” around the lesion (arrow). There is no significant mass effect. B. Coronal T2WI shows an ovoid lesion (1.7cm×1.3cm×1.0cm) perpendicular to the cerebral ventricle (arrow).

Technique: 3.0T Signa HD (GE, USA) MR scanner. 5.0mm slice thickness. T1WI (T1-FLAIR): TR=2580ms, TE=16ms, TI=860ms. T2WI: TR=3280ms, TE=108ms.

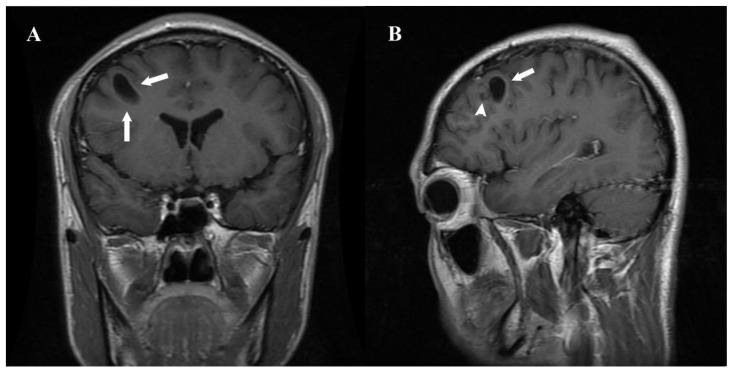

Figure 4.

25-year-old male with angiocentric glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Findings: A. Coronal postcontrast T1WI (T1-FLAIR) demonstrates a well defined non-enhancing lesion located in the sub-cortical white matter (arrow). B. Sagittal postcontrast T1WI demonstrates a small non-enhancing area of calcification (arrowhead) anterior to the lesion (arrow).

Technique: 3.0T Signa HD (GE, USA) MR scanner. 5.0mm slice thickness. T1WI (T1-FLAIR): TR=2580ms, TE=16ms, TI=860ms. Contrast material and dose: Gadolinium 0.2ml/Kg.

Treatment

The patient underwent right frontal lobe craniotomy with gross total resection. Intraoperative findings showed slight enlargement of the cortical gyri and narrowing of adjacent sulcus around the lesion, which contained a large cystic cavity filled with clear yellow fluid. Post-operatively, patient received anti-epileptic medications for three months.

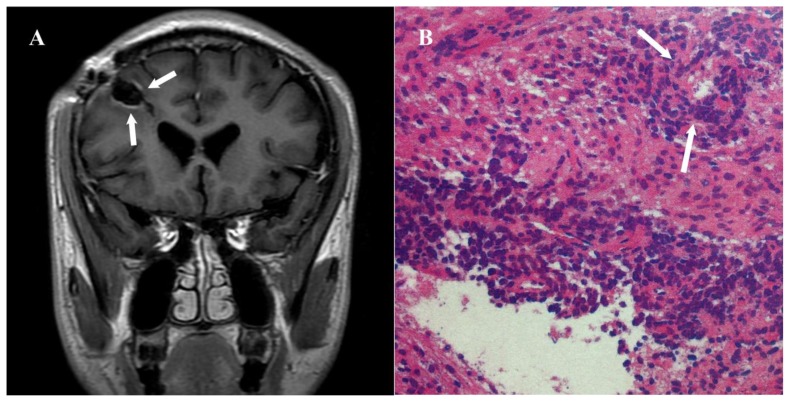

Histopathology examination demonstrated that bipolar single cells were centered around the cortical blood vessels (Fig. 5). Immunohistochemistry was positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Vimentin and S-100 protein, and negative for NeuN. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) demonstrated tiny positive staining. The Ki-67 prolifration index was 1–3%. Pathologic diagnosis confirmed angiocentric glioma (WHO?).

Figure 5.

25-year-old male with angiocentric glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Findings: A. There is no evidence of tumor recurrence on three months follow-up postcontrast TIWI (T1-FLAIR) (arrow). B. Histopathology examination showed that bipolar single cells were centered around the blood vessels (arrow).

Technique: 3.0T Signa HD (GE, USA) MR scanner. 5.0mm slice thickness. T1WI (T1-FLAIR): TR=2580ms, TE=16ms, TI=860ms. Contrast material and dose: Gadolinium 0.2ml/Kg.b) Posterior view shows abnormal increased uptake in the left parotid gland (arrow).

The patient recovered post-operatively without complications or neurologic sequelae. On 6 months follow up, the patient had no clinical evience of recurrence (Fig 5). Patient will continue to undergo routine follow up to assess for recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Etiology and Demographics

Angiocentric glioma, which is a tumor related to epilepsy, was first classified in the 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System (CNS) [1]. It presents as epilepsy in most patients. Angiocentric glioma was initially reported by two separate research groups in 2005 [2, 3]. Here we give a brief review of 59 angiocentric gliomas [2–25] reported in the literature. They are all solid or partial cystic lesions. We report a cystoid angiocentric glioma case perpendicular to the ventricle. The pathogensis of this tumor type remains unclear. Wang considered this tumor as a mixed astrocytic and ependymal differentiation [2]. Preusser suggested that it might be derived from radial glia [4]. Angiocentric glioma predominantly affects young adults.

Clinical & Imaging findings

Table 1 shows the clinical and imaging characteristics of the 59 reported cases of angiocentric gliomas. The age range of these patients is 2 to 70 years with an average age of 16.33 years. Both male and females are equally affected with a male to female ratio of 1. The main clinical feature is intractable epilepsy, which is characterized as generalized tonic-clonic seizures, partial complex seizures and psychomotor seizures. The frequency of seizures ranged from 1 episode monthly to 20–30 daily episodes in 14 of the reported cases. The location of the 59 cases of angiocentric gliomas were in the superficial lobes with the temporal and frontal lobes being the most common sites. 6 cases were located in the hippocampus (6/59, 10.17%). Typical locations are the cortex and sub-cortical white matters. 54 cases were solid lesions, associated with ill-defined hyper-intensity on T2WI and FLAIR. Due to calcifications or hemorrhage, the lesion is heterogenously intense on T1WI. Calcifications were rare (3/59, 5.08%) [3, 4, 24]. The presence of cortical high signal “rim” on T1WI might be related to long-term lesion compression. MRI with contrast was performed for 47 cases of which 40 (40/47, 85.11%) were non-enhancing. Only 5 (5/59, 8.47%) cases [4, 5, 6, 7] were cystic or partial cystic lesions. Some showed stalk-like extension to the cerebral ventricle, which was first reported by Lellouch-Tubiana [3]. This imaging feature is also seen in dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs) and dysplasias, which suggests angiocentric gliomas may share both dysplasic and neoplastic origins. Cortical hyper-intense “rim” on T1WI and stalk-like extension to the cerebral ventricle on T2WI are MRI characteristics of angiocentric gliomas.

Table 1.

Clinical and Imaging Characteristics of 59 Cases of Angiocentric Gliomas.

| Groups | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | Children (0–6) | 16 | 27.12% |

| Juveniles (7–17) | 27 | 45.76% | |

| Young adults (18–46) | 12 | 20.34% | |

| Middle adults (45–59) | 3 | 5.08% | |

| Elderly (>60) | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Symptoms | Epilepsy | 45 | 76.27% |

| Headache and dizziness alone | 4 | 6.78% | |

| Vision and hearing loss | 4 | 6.78% | |

| Epilepsy with headache | 3 | 5.08% | |

| Developmental delay | 2 | 3.39% | |

| Auditory hallucinations | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Location | Temporal lobe | 22 | 37.29% |

| Frontal lobe | 17 | 28.81% | |

| Parietal lobe | 7 | 11.86% | |

| Occipitoparietal lobe | 4 | 6.78% | |

| Frontotemporal lobe | 2 | 3.39% | |

| Frontoparietal lobe | 2 | 3.39% | |

| Temporo-parietal lobe | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Occipital lobe | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Insular lobe | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Midbrain | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Thalamus | 1 | 1.69% | |

| Solid/Cystic | Solid | 54 | 91.53% |

| Cystic | 5 | 8.47% | |

| Contrast-enhancement | No enhancement | 40 | 40/47, 85.11% |

| Slightly enhancement | 5 | 5/47, 10.64% | |

| Significant enhancement | 2 | 2/47, 4.26% | |

| Not available | 12 | - |

Treatment & Prognosis

Angiocentric gliomas generally causes epilepsy with most of the affected patients juveniles. The first line treatment is surgical resection. Table 2 shows the treatment and prognosis of the 57 reported cases of angiocentric gliomas. 90.24% patients were seizure-free after gross total surgical resection. Mott [5] reported a patient who underwent fractionated radiation therapy for a tumor located in the cortical region associated with motor functions. The treatment result in a 50% reduction in tumor size and the patient had no seizure episodes at 5 months follow-up. Post-operatively, most patients do not require radiation or chemotherapy, however, radiation treatment is recommended for tumors located in the functional area [5]. One patient (1/57, 1.75%) who underwent partial resection plus radiotherapy and chemotherapy, had tumor recurrence and died of angiocentric glioma [2]. Chen [8] found that the range of abnormal brain discharges exceeded the area of the tumor by using intraoperative cortical electroencephalogram monitoring. Chen et al proposed that it was the reason why 38.46% patients were not seizure free after subtotal resections. For these cases, more extensive resection is needed to control epilepsy.

Table 2.

Treatments and Prognoses of 57 Cases of Angiocentric Gliomas. (Two cases were excluded because of the prognoses were not available.)

| Seizure-free | Seizures or headaches | Recurrence | Death | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTR | 37 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 41 (71.93%) |

| STR | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 13 (22.81%) |

| Biopsy, radiotherapy | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.51%) |

| Biopsy alone | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.75%) |

The final diagnosis of angiocentric glioma is confirmed histopathologically, which is characterized by monomorphous bipolar cells, an angiocentric growth pattern and immunoreactivity for GFAP, Vimentin and S-100 protein, but not for Synaptophysin (Syn) or NenN. Due to its non-agresssive clinical behavior, angiocentric glioma is assigned to WHO grade I [1]. Most typical angiocentric gliomas are indolent, slow growing and exhibits Ki-67 less than 5%. There are only four reported cases (4/59, 67.80%) with elevated proliferation index [2, 9, 10, 11].

Differential Diagnoses

Ganglioglioma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, and DNETs are main differential diagnosis, and are all commonly located in the temporal lobe.

Ganglioglioma is a well-circumscribed lesion with cystic components and calcification on CT, and about 50% of them show contrast enhancement [26]. The tumors with solid and cystic components are defined by hypo-intense signals on T1WI with homogeneous enhancement of solid portion, and hyper-intense signals on T2WI. Cystic tumors are more common in young pediatric patients (mean age of 5.5 years, 83%) than in adults (mean age of 25.6 years, 63%) [27].

One-third of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma demonstrate hemorrhage on CT, but calcification is rare. Cysts, inner table scalloping, extensive vasogenic edema, and contrast enhancements in the mural nodule on MRI are the characteristic manifestation of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Relatively low ADC values of the solid components help to differentiate these tumors from other low-grade supratentorial, peripheral tumors [28].

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs) are typically low density non-calcified mass on CT. The tumor is hypo-intense on T1WI and hyper-intense on T2WI. Adjacent cortical thickening is a characterisitc feature of DNET, which helps to differentiate it from other benign tumors [29, 30].

Conclusion

The characteristics of angiocentric glioma are summarized as follows: (1) the tumors occur predominantly in young age; (2) Seizure is the primary clinical presentation; (3) MRI shows non-enhancing hyper-intense lesions on T2WI, which are located supratentorially, predomantly located in the temporal lobe; (4) The tumor has typical pathological features; (5) Total surgical resection is associated with a favorable outcome. However tumors located in the functional area requires post- operative chemotherapy or radiation treatments.

TEACHING POINT

Angiocentric glioma is a rare tumor associated with epilepsy. On MRI it is characterized by cortical hyper-intense “rim” on T1WI and ovoid lesion perpendicular to the cerebral ventricle on T2WI. It is histopathologically characterized by monomorphous bipolar cells with angiocentric growth pattern.

Table 3.

Summary table for angiocentric glioma.

| Etiology | A subtype of neuroepithelial tumor, but the cytogenesis of this kind of tumor remains unclear. |

| Incidence | Rare, with 59 reported cases |

| Gender ratio | Of the 59 cases, there was no gender predilection and the male to female ratio was 1. |

| Age predilection | Age range of 2 to 70 years with an average age of 16.33. |

| Risk factor | Unknown |

| Treatment | Gross total surgical resection is recommended. Radiotherapy is necessary for tumors located in the functional area. |

| Prognosis | 90.24% patients were seizure-free after gross total surgical resection. |

| Findings on imaging | MRI: supratentorial lobe, predominantly in the temporal lobe; hyper-intense lesion on T2WI without enhancement, cortical hyper-intense “rim” in T1WI and stalk-like extension to the cerebral ventricle in T2WI. |

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis for angiocentric glioma.

| Entity | CT findings | MRI findings |

|---|---|---|

| Angiocentric glioma |

|

|

| Ganglioglioma |

|

|

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma |

|

|

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET) |

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CT

Computed Tomography

- DWI

Diffusion weighted image

- EMA

Epithelial membrane antigen

- FLAIR

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GTR

Gross total resection,

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- STR

Subtotal resection

- T1WI

T1-weighted image

- T2WI

T2-weighted image

- WHO

World Health Organization

REFERENCES

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Tihan T, Rojiani AM, Bodhireddy SR, Prayson RA, Iacuone JJ, et al. Monomorphous angiocentric glioma: a distinctive epileptogenic neoplasm with features of infiltrating astrocytoma and ependymoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(10):875–881. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000182981.02355.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lellouch-Tubiana A, Boddaert N, Bourgeois M, Fohlen M, Jouvet A, Delalande O, et al. Angiocentric neuroepithelial tumor (ANET): a new epilepsy-related clinicopathological entity with distinctive MRI. Brain Pathol. 2005;15(4):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preusser M, Hoischen A, Novak K, Czech T, Prayer D, Hainfellner JA, et al. Angiocentric glioma: report of clinico- pathologic and genetic findings in 8 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(11):1709–1718. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804a7ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mott RT, Ellis TL, Geisinger KR. Angiocentric glioma: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38(6):452–456. doi: 10.1002/dc.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shakur SF, McGirt MJ, Johnson MW, Burger PC, Ahn E, Carson BS, et al. Angiocentric glioma: a case series. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3(3):197–202. doi: 10.3171/2008.11.PEDS0858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buccoliero AM, Castiglione F, Degl’innocenti DR, Moncini D, Spacca B, Giordano F, et al. Angiocentric glioma: clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular features in three pediatric cases. Clin Neuropathol. 2013;32(2):107–113. doi: 10.5414/NP300500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G, Wang L, Wu J, Jin Y, Wang X, Jin Y. Intractable epilepsy due to angiocentric glioma: A case report and minireview. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7(1):61–65. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugita Y, Ono T, Ohshima K, Niino D, Ito M, Toda K, et al. Brain surface spindle cell glioma in a patient with medically intractable partial epilepsy: a variant of monomorphous angiocentric glioma? Neuropathology. 2008;28(5):516–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pokharel S, Parker JR, Parker JC, Jr, Coventry S, Stevenson CB, Moeller KK. Angiocentric glioma with high proliferative index: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2011;41(3):257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu JQ, Patel S, Wilson BA, Pugh J, Mehta V. Malignant glioma with angiocentric features. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;11(3):350–355. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.PEDS12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arsene D, Ardeleanu C, Ogrezeanu I, Danaila L. Angiocentric glioma: presentation of two cases with dissimilar histology. Clin Neuropathol. 2008;27(6):391–395. doi: 10.5414/npp27391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyata H, Ryufuku M, Kubota Y, Ochiai T, Niimura K, Hori T. Adult-onset angiocentric glioma of epithelioid cell-predominant type of the mesial temporal lobe suggestive of a rare but distinct clinicopathological subset within a spectrum of angiocentric cortical ependymal tumors. Neuropathology. 2012;32(5):479–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lum DJ, Halliday W, Watson M, Smith A, Law A. Cortical ependymoma or monomorphous angiocentric glioma? Neuropathology. 2008;28(1):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koral K, Koral KM, Sklar F. Angiocentric glioma in a 4-year-old boy: imaging characteristics and review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 2012;34:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenzweig I, Bodi I, Selway RP, Crook WS, Moriarty J, Elwes RD. Paroxysmal ictal phonemes in a patient with angiocentric glioma. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(1):123. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.1.123.e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexandru D, Haghighi B, Muhonen MG. The treatment of angiocentric glioma: case report and literature review. Perm J. 2013;17(1):e100–102. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulton SP, Clarke DF, Wheless JW, Ellison DW, Ogg R, Boop FA, et al. Angiocentric glioma-induced seizures in a 2-year-old child. Child Neurol. 2009;24:852. doi: 10.1177/0883073808331078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covington DB, Rosenblum MK, Brathwaite CD, Sandberg DI. Angiocentric glioma-like tumor of the midbrain. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45(6):429–433. doi: 10.1159/000277616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marburger T, Prayson R. Angiocentric glioma: a clinicopathologic review of 5 tumors with identification of associated cortical dysplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(8):1037–1041. doi: 10.5858/2010-0668-OAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li JY, Langford LA, Adesina A, Bodhireddy SR, Wang M, Fuller GN. The high mitotic count detected by phospho-histone H3 immunostain does not alter the benign behavior of angiocentric glioma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2012;29(1):68–72. doi: 10.1007/s10014-011-0062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X, Ge J, Wang L, Xia C, Liu H, Li Y, et al. A 25-year-old woman with a mass in the hippocampus. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(2):503–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu XW, Zhang YH, Wang JJ, Jiang XF, Liu JM, Yang PF. Angiocentric glioma with rich blood supply. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17(7):917–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rho GJ, Kim H, Kim HI, Ju MJ. A case of angiocentric glioma with unusual clinical and radiological features. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;49(6):367–369. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.49.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takada S, Iwasaki M, Suzuki H, Nakasato N, Kumabe T, Tominaga T. Angiocentric glioma and surrounding cortical dysplasia manifesting as intractable frontal lobe epilepsy--case report. Neurol Med Chir. 2011;51(7):522–526. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo M, Davis PC, Takei Y, Hoffman JC., Jr Intracranial ganglioglioma: MR, CT, and clinical findings in 18 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154(3):607–612. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.3.2106228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Provenzale JM, Ali U, Barboriak DP, Kallmes DF, Delong DM, McLendon RE. Comparison of patient age with MR imaging features of gangliogliomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(3):859–862. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore W, Mathis D, Gargan L, et al. Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma of Childhood: MR Imaging and Diffusion MR Imaging Features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24994821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Paudel K, Borofsky S, Jones RV, Levy LM. Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor with atypical presentation: MRI and diffusion tensor characteristics. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(11):7–14. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v7i11.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanescu Cosson R, Varlet P, Beuvon F, et al. Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors: CT, MR findings and imaging follow-up: a study of 53 cases. J Neuroradiol. 2001;28:230–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]