Abstract

PURPOSE

Patients and doctors report marked disenchantment with primary care consultation experiences relating to osteoarthritis. This study aimed to observe and analyze interactions between general practitioners (GPs) and patients presenting with osteoarthritis (OA) to identify how to improve care for OA.

METHODS

We conducted an observational study in general practices in the United Kingdom using video-recorded real-life consultations of unselected patients and their GPs. Postconsultation interviews were conducted using video-stimulated recall. Both consultations and interviews were analyzed thematically.

RESULTS

Three key themes were identified in an analysis of 19 OA consultations and the matched GP and patient interviews: complexity, dissonance, and prioritization. The topic of osteoarthritis arises in the consultation in complex contexts of multimorbidity and multiple, often not explicit, patient agendas. Dissonance between patient and doctor was frequently observed and reported; this occurred when GPs normalized symptoms of OA as part of life and reassured patients who were not seeking reassurance. GPs used wear and tear in preference to osteoarthritis or didn’t name the condition at all. GPs subconsciously made assumptions that patients did not consider OA a priority and that symptoms raised late in the consultation were not troublesome.

CONCLUSIONS

The lack of a clear illness profile results in confusion between patients and doctors about what OA is and its priority in the context of multimorbidity. This study highlights generic communication issues regarding the potential negative consequences of unsought reassurance and the importance of validation of symptoms and raises new arguments for tackling OA’s identity crisis by developing a clearer medical language with which to explain OA.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, arthralgia, primary care, clinic visits, physician-patient relations, multiple morbidities, diagnosis, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common cause of musculoskeletal pain in older people and is globally the fastest increasing cause of years lived with disability.1 Although a range of international guidance exists for OA management, guidelines agree on the core importance of patient education and self-management in the treatment of this long-term condition.2–8

Patients may encounter any of a number of problems getting their OA managed. First, patients appear not to consult their primary care physicians (general practitioners [GPs] in the United Kingdom) as frequently for OA as they do for some other long-term conditions. A number of studies report relatively low consultation rates9–13: only 17% of patients with OA consult annually.10 One reason for this may relate to dissatisfaction with OA consultations. Both patients and doctors report “negative talk” in consultation concerning OA, namely that OA is to be expected, that it involves an inevitable decline, and that little can be done about it.14 Second, there is a gap between the care that is recommended and the care patients receive. Fewer than one-third of patients with OA report having received treatment as recommended by UK guidelines.15,16 Identifying the reasons for these problems would help to develop strategies to optimize the care of patients with OA. We have little evidence of what goes on in the OA consultation; research about the content and experience of consultations based solely on postconsultation interviews may not reflect what actually happens in the consultation.14

The aim of this study was to investigate the language, explanations, and exchanges that occur in general practice consultations with patients who have OA and ultimately to identify how to improve the delivery of effective care and positive management of OA.

METHODS

Design

This study involved observation of real-life general practice consultations using video recordings. Physicians and patients were interviewed after their consultations and shown their own consultation video recordings to enhance and enrich their accounts using video-stimulated recall.17 Information on comorbidity and previous consultations was collected by medical record review. The study received ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Committee Northwest—Greater Manchester East (11/H1013/3), and all participants gave full written consent. GPs were told that the study concerned chronic musculoskeletal conditions.

Setting

The study took place in 7 general practices in the United Kingdom between August 2012 and August 2013. GPs in the United Kingdom are qualified medical practitioners who undergo 4 years postgraduate training and pass an exit examination in primary care.

Participant Recruitment and Selection

GPs in practices belonging to local research networks were invited to participate. Each consenting GP nominated 2 half-day clinics to be video recorded, in which consecutive, eligible patients aged over 45 years were approached for consent. Patients gave consent for video recording before and after the consultation and 48 hours later, by telephone. In the 48 hours following the consultation, all video recordings were viewed to determine whether OA had been discussed. The decision was made using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Patients and GPs participating in OA consultations were invited for interviews within 2 weeks of the consultation where possible. Review of the medical records was conducted to gather information about multimorbidity, OA history, and previous consultations.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Selection of Index Consultations

| Inclusion |

| GP used terms wear and tear, arthritis, or osteoarthritis diagnostically. |

| GP gave no diagnosis, but findings support diagnosis of OA based on criteria recommended by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) OA Guideline Development Group18: • Persistent joint pain worse with use • Patient aged 45 years and over • Morning stiffness lasting no more than 30 minutes |

| Exclusion |

| GP diagnosed a regional soft tissue problem or a generalized soft tissue problem such as fibromyalgia. |

| GP gave no diagnosis, but the researcher felt a soft tissue diagnosis to be more likely than OA. |

| Inflammatory arthritis (or suspected inflammatory arthritis) was apparent during consultation or present on medical record if the researcher’s clinical suspicion prompted a review of the record. |

| Malignancy was apparent during consultation or present on the medical record. |

| GP referred the patient to secondary care because of diagnostic uncertainty. |

| Patient had only spinal symptoms. |

GP = general practitioner; OA = osteoarthritis, UK = United Kingdom.

Postconsultation Interviews

Postconsultation semistructured interviews were conducted and audio-recorded by 1 of the authors (Z.P.). The general practitioners were asked to describe a typical OA consultation before being shown their video recorded consultation. Patients were asked about their recollections of the consultation, antecedents to the consultation, and their expectations of the consultation before video playback. Differences in recalled and observed events were explored.

Data Capture, Coding, and Analysis

The consultations and interviews were transcribed verbatim. We analyzed the transcripts to identify themes and coded them using NVivo V9.0 software (QSR International Pty Ltd). From the results, we produced an overarching map of all themes. The themes were subsequently analyzed at a more interpretative level, with constant comparison within cases (a case being a matched consultation, patient interview, and doctor interview) and across cases; eg, across all doctor interviews. Quantitative measures, including the number of items discussed and the length of the consultation in minutes, were recorded.

In a systematic attempt to avoid ‘doctor-centric’ analysis and gain balance, a sociologist and qualitative researcher (T.S.) and a rheumatologist (Z.P.) analyzed the transcripts in parallel and discussed their findings. The final interpretative themes were the product of discussions involving the other authors, a professor of medical education, (A.B.H.), and a GP and professor of epidemiology (P.R.C.).

RESULTS

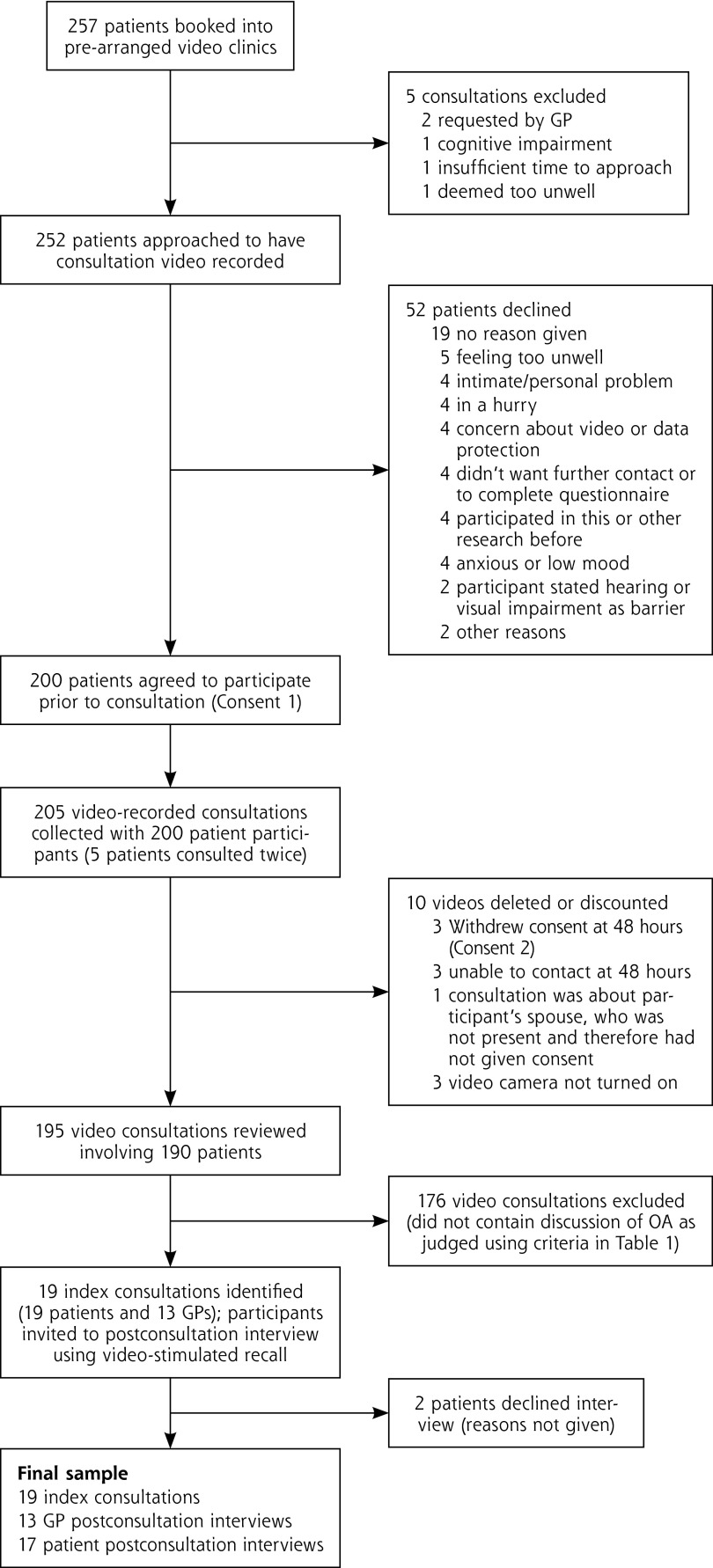

Fifteen GPs from 7 different practices participated. Figure 1 details the patient recruitment and consultation selection. Of patients approached, 79.4% consented. The GP practices varied in size from 1,800 to 3,800 patients and covered areas with a deprivation decile of 6 or higher, where 1 is the most deprived and 10 is the least deprived. Three of the 15 GPs were female, 7 were GP trainers (experienced in using video), and the median number of years worked as a GP was 17 (range 3 to 29).

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment and selection of index consultations.

GP = general practitioner; OA = osteoarthritis

The consultations are detailed in Table 2. GPs verified that the included patients had OA. Three overarching themes were identified in the analysis: complexity, dissonance, and prioritization; these are discussed individually below. Supporting quotations are listed in the Supplemental Appendix, which is available at http://annfammed.org/content/13/6/537/DC1. Quotations are referred to in the text by parenthesized numbers, such as “(Q1).”

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients and Consultations

| Consultation No. | Patient Demographics

|

Joint(s) Discussed in Order Presented, Most Symptomatic in Bolda | New Problem or Follow-upb | OA-Related Read Codec | Joint Pain Primary or Secondary Complaintd | Other Problems Discussed, No. | Consultation Length, min

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Total | Time on OA (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 62 | Female | Hip, knee, back | Follow-up | No | Primary | 3 | 14:10 | 08:46 (61.9) |

| 2 | 65 | Male | Hip, back | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 1 | 07:00 | 05:56 (84.8) |

| 3 | 75 | Female | Shoulder, neck, knee | Follow-up | Yes | Primary | 0 | 16:14 | 16:14 (100) |

| 4 | 69 | Male | Knee | New | Yes | Secondary | 2 | 12:44 | 01:00 (7.9) |

| 5 | 70 | Male | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Primary | 0 | 12:17 | 12:17 (100) |

| 6 | 79 | Male | Neck, hip | New | Yes | Secondary | 3 | 10:44 | 01:51 (17.2) |

| 7 | 65 | Female | Knee, hip | New | No | Secondary | 2 | 13:36 | 00:45 (5.5) |

| 8 | 49 | Male | Knee | New | No | Secondary | 4 | 20:23 | 10:72 (54.9) |

| 9 | 67 | Female | Hip | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 1 | 06:40 | 01:15 (18.8) |

| 10 | 75 | Female | Hip, knee | New | Yes | Secondary | 4 | 12:16 | 00:50 (6.8) |

| 11 | 74 | Female | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 3 | 18:29 | 01:49 (9.8) |

| 12 | 79 | Female | Knees, hip | Follow-up | Yes | Primary | 0 | 08:36 | 08:36 (100) |

| 13 | 72 | Female | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 1 | 09:21 | 02:37 (28) |

| 14 | 65 | Male | Knee | New | No | Primary | 2 | 10:05 | 8:05 (80.2) |

| 15 | 65 | Female | Hip | New | No | Secondary | 3 | 12:53 | 01:10 (9.1) |

| 16 | 61 | Female | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 2 | 08:49 | 06:00 (68.1) |

| 17 | 84 | Female | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Secondary | 4 | 22:42 | 00:25 (1.8) |

| 18 | 62 | Female | Hands, feet | New | No | Primary | 0 | 09:44 | 09:44 (100) |

| 19 | 85 | Female | Knee | Follow-up | Yes | Primary | 1 | 20:20 | 20:00 (98.4) |

OA = osteoarthritis

Spinal pain was not the focus of the study, and patients with spinal pain only were excluded. It is mentioned here where spinal symptoms were discussed in conjunction with peripheral joint OA to illustrate how many patients had multisite pain. Areas of spinal pain listed in this column are italicized.

New in this column indicates that the patient had either not discussed the most symptomatic joint with the GP before (data derived from the medical record and patient report) or that the patient was seeing the GP for results following the first consultation.

Evidence of previous medical record entry of OA in any joint.

Primary complaint is defined as the first presenting complaint mentioned to the GP in the consultation.

Complexity

Complexity was a prominent feature of the consultations, manifested in the number of items discussed, the interrelation of comorbid conditions, and the flow of conversation from one item to another. All patients had comorbid conditions (a median of 5 per patient) and 15 of the 19 consultations contained talk about multiple items, with a median of 3 per 13-minute consultation.

Where multiple items were discussed and dealt with sequentially, eg, following up hypertension and looking at a skin lesion, the consultation was able to maintain structure and order (Q1). With discussion time devoted to other topics, of course, less time was spent on OA even in the most structured consultations (Table 2).

The complex consultation was less ordered when talk kept moving between unrelated topics. The patient’s consulting style appeared to influence structure, and in some consultations, disorder resulted. For example, 5 issues were discussed in Consultation 10, with the topic of talk changing 16 times. Some patients initiated topic shifts when GPs were talking. In 1 example, the patient talked over a GP, introducing a new topic while the GP was handing the patient an order for x-ray imaging (Q3). The interjection interrupted the GP’s flow and the completion of their “closing talk”; the GP did not return to OA and did not ask the patient to come back for the x-ray results. After the consultation, the GP thought he/she had asked the patient to return for the results; the patient assumed the GP had “nothing more to offer.”

The interrelation between comorbid conditions contributed to complexity, particularly when other conditions were implicated as barriers to OA treatment, or OA was presented as a barrier in managing a comorbid condition. This was evident, for example, in a patient whose inability to exercise due to angina hampered management of OA of the knees (Q3). A complex relationship existed between the patient’s poorly controlled angina, weight gain and arthritis. In this example, the GP closed discussion of joint pain to pursue angina treatment; this was rationalized in the postconsultation interview as pursuing the condition that was the greatest threat to the patient’s health.

Dissonance

Dissonance, misalignment of patient and physician expectations or agendas, was both observed during consultation analysis and reported by participants in postconsultation interviews. Patient expectations of the consultation varied significantly, with some wanting information, some being exclusively focused on symptom relief, and others desiring a combination of information and active management. Similarly, GPs varied in how focused they were on offering information or symptom management. Dissonance occurred in 3 main circumstances discussed below.

Dissonance Due to GP Emphasis on Reassurance

Patients who were seeking clear diagnostic information, not reassurance, described feeling that their concerns were not validated when the GP downplayed or normalized symptoms or otherwise provided reassurance. GPs were observed to use talk implying that OA is normal as a strategy to reassure, facilitate acceptance, or conclude the consultation (Q4).

Only 2 GPs mentioned the term osteoarthritis in a consultation (Consultations 14 and 18); in both of these instances the term was used as part of a general explanation, not used diagnostically. In one-half of the consultations that contained new presentations of OA (4 of 8), the GPs gave no diagnostic label. Wear and tear and arthritis were the most common terms physicians used. GPs described a strong reassurance agenda, which underpinned their explanations for their using the term osteoarthritis infrequently. They felt the term to be alarmist (Q8–9). Many patients, however, wanted a clearer and more meaningful diagnosis (Q7).

Although physicians described wear and tear as synonymous with OA, patients did not share the same meaning, and most were unsure about the meaning of the term (Q10).

When GPs were observed to give a diagnosis of OA, it was based on x-ray findings, with GPs borrowing terms directly from reports. In the brief exchanges about diagnosis that were observed, GPs spent more time explaining what OA wasn’t (rheumatoid arthritis) than what it was; again, their approach was shaped by a strong reassurance agenda. The diagnosis of OA therefore became a diagnosis of exclusion, after other conditions, particularly rheumatoid arthritis, had been ruled out. The patient could then interpret the lack of diagnostic specificity as “nothing showing” and “nothing being done” (Q11).

In addition to describing symptoms as “normal” or “to be expected,” some GPs downplayed the significance of symptoms, using terms such as early onset or talking down the significance of radiology reports (Q5–6). GPs also described the need to play down OA to avoid encouraging the patient to adopt the “sick role.” Patients also talked about joint pain being “normal”; however, dissonance in the consultation resulted when patients felt the messages about OA being normal or early onset failed to validate the importance and impact of their symptoms (Q6).

Dissonance Resulting From Unmet Information Needs

Patients commonly felt the need for information about diagnosis, self-management, employment, and prognosis; dissonance resulted when these needs were not met (Q12). In the absence of a clearly articulated patient agenda, GPs appeared to favor offering active management plans over information. One GP described the importance of education in the interview, then reflected on potential dissonance after viewing the consultation and observing his/her own tendency to offer action over information (Q13). Some GPs did not recognize patient education as a priority, and others reflected that they might not have the knowledge to provide the necessary education (Q14–15).

A further complicating issue was that patients were often not explicit about their needs even when asked directly about their expectations, suggesting that they may not have had a clear preconsultation agenda.

Dissonance as a Result of Management Perceived to be Not Active Enough

Dissonance in this circumstance was less commonly observed than the other 2 sources of dissonance, but was reported by patient participants in 2 postconsultation interviews (Q16).

Prioritization

Some GPs felt that patients assigned joint pain a low priority, assuming it to be a normal consequence of aging (Q17). Not all patient participants held this view, however.

When multiple problems were raised, only one physician put a strategy for prioritization into words in the consultation (Q1). In the postconsultation interviews, GPs described influences on prioritization such as patient safety and conditions for which management is financially incentivized. Prioritization was also influenced by availability of resources such as physical therapy. GPs also described choosing problems to address where they felt they could be most useful (Q20).

In 6 consultations where new presentations of OA were raised, the symptoms of joint pain were brought up after discussion of other topics (Table 2). Some GPs described frustration with patients’ “late-arising concerns.” Others assumed that joint pain mentioned late in the consultation was unlikely to be troublesome and was a result of the patient making conversation (Q18). Analysis of the consultations and patient interviews identified other explanations: either the patient had mentioned joint pain early in the consultation and the doctor had not pursued it or the patient articulated other reasons for being hesitant to discuss joint pain (Q19).

DISCUSSION

This study’s findings demonstrate that OA appears in complex contexts of multimorbidity against a backdrop of multiple and varied patient and physician expectations. A central feature of the observed and reported dissonance of patient and physician expectations concerns communication, or lack of it, complicated by the tendency of patient or physician or both to normalize symptoms, by physicians’ attempts to reassure patients who were not looking for reassurance, and by physicians’ failure to meet their patients’ information needs. OA is diagnosed by exclusion, with more talk about absence of disease than positive pragmatic explanations and advice. OA and joint pain tend to be deprioritized by both patients and physicians, for a range of complex, often unarticulated reasons. As a result of all this, little time is devoted to discussion of OA, and patients are given only minimal information about it. The construct of OA is vague, and we appear to lack clear medical language to describe and explain the condition. OA is experiencing an identity crisis.

Many of the findings in this study relating to physician-patient communication are not specific to OA. Physicians and patients have been described as colluding in “demedicalizing” and normalizing depression, favoring a societal explanation that depression is justifiable.1 Parallels also exist with research studying consultations of patients with medically unexplained symptoms; normalization, reassurance, and “no disease” explanations left patients feeling rejected and were associated with a less empathic physician style.20–22 Furthermore, avoidance of diagnostic labels in gastroenteritis and tonsillitis has been associated with reduced perceived validation of symptoms.22 Failure to elicit patient beliefs and expectations is commonly cited as the reason consultations may “go wrong”24,25; this study also demonstrates the importance of the therapeutic relationship in validating the patient’s symptoms, as reported in other conditions, eg, back pain.25 One of the major challenges to maintaining the therapeutic relationship is the complexity that multimorbidity brings to the consultation. This study’s findings support the notion that the single-disease framework is no longer a relevant model for primary care,27 and communication skills training for primary care physicians needs to be mindful of this context.

The perception that evidence-based treatments for OA have limited effectiveness has previously been identified as a problem for GPs in managing the condition.14 This study identified a number of additional barriers; they are summarized in Table 3. Previously, researchers have advocated avoidance of the term osteoarthritis because of the difficulty of correlating the diagnostic test (radiography) with symptoms, diagnosis, and outcome and because of concern about the potential for harm from the label.28 While we agree with the sentiments underlying that proposal and with suggestions that OA should not be overtreated or overmedicalized,29 our empirical study does suggest that a formal language is needed for holistic components of OA care such as patient education and self-management support. The findings suggest that use of the term osteoarthritis could help in validating patient suffering, could reduce dissonance in the consultation, and could be a necessary first step in giving information.

Table 3.

Barriers to Use of the Term Osteoarthritis and the Discussion of Osteoarthritis Identified in This Study

| The predominance of the societal construct of OA that suggests it is part of normal life/aging process |

| Omission of OA in the UK government-led quality of care initiative |

| Limited or uneven access to treatment resources such as physical therapy |

| Lack of knowledge about the prognosis of OA |

| Lack of clear language for positive diagnosis and explanation of OA |

| Inconsistent interpretation of language in radiology reports |

| Concern that diagnosis may result in harm or adoption of “sick role” |

OA = Osteoarthritis; UK = United Kingdom

A major strength of this study is the methodology: using a combination of data sources to understand the context and interactional components of the consultation and to consider both physician and patient perspectives. Consent rates in the video phase of the study were just under 80%, in line with similar published studies,30 and the osteoarthritis consultations were drawn from a large, unselected sample. However, the characteristics of GPs and practices involved may not be representative of the United Kingdom as a whole, with few patient participants from ethnic minorities and no practices from more deprived areas. Generalizability to other cultures and health systems is also limited. The camera may have had an influence on behavior; some participants reported that they (or their counterparts) were trying to “behave better,” consciously or otherwise.

In summary, this study raises new arguments for developing a clearer medical language with which to explain OA in general practice consultations. We need to be able to deliver a clear account of osteoarthritis that covers what it is and what the prognosis is. This is likely to be useful in avoiding uncertainty, providing structure for the consultation and facilitating holistic medical care that encompasses self-management. This study also highlights more generic communication difficulties around failure to validate concerns and elicit patient expectations; these difficulties are likely to be influenced by the complexity that multimorbidity introduces into the modern-day consultation. The obvious next step would be to work with patients and doctors to create GP training and patient information packages and to test their efficacy in improving the consultation experience.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Prof Christian Mallen and Dr Mark Porcheret for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also wish to thank and acknowledge the help of Chan Vohara, Debbie D’Cruz, and Charlotte Purcell for administrative support; Prof RK McKinley, Prof Chris Main, and Prof Krysia Dziedzic for input in study design; and the participating GPs and patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research program (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0407-10386). Peter Croft is a UK National Institute of Health Research Senior Investigator. Tom Sanders, PhD, was supported in the preparation/submission of this article by the Translating Knowledge into Action Theme of the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Yorkshire and Humber (http://clahrc-sy.nihr.ac.uk).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Previous presentations: This work has been presented at the American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting; November 14–19, 2014; Boston, Massachusetts; and at the British Society of Rheumatology conference; April 29 – May 1, 2014; Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/13/6/537/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2013;381(9867):628]. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Clinical Guideline Centre. Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults. Guideline no. CG177. London, England: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb BF, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007; 66(3):377–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. ; European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1125–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, et al. ; EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(4):476–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedson J, Mottram S, Thomas E, Peat G. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in the general population: what influences patients to consult? Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(2):91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill S, Dziedzic K, Thomas E, Baker SR, Croft P. The illness perceptions associated with health and behavioural outcomes in people with musculoskeletal hand problems: findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(6):944–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jinks C, Jordan K, Ong BN, Croft P. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST). 2. Results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004; 43(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, et al. Population survey comparing older adults with hip versus knee pain in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(512):192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paskins Z, Sanders T, Hassell AB. Comparison of patient experiences of the osteoarthritis consultation with GP attitudes and beliefs to OA: a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S, et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with 32 quality indicators: National population survey of adults aged 50 or more in england. BMJ. 2008;337:a957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, Croft P; Primary Care Rheumatology Society. Primary care treatment of knee pain—a survey in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(11):1694–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paskins Z, McHugh GA, Hassell ABH. Getting under the skin of the primary care consultation using video stimulated recall: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(101):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Clinical Guideline Centre. The Care and Management of Osteoarthritis in Adults. Guildeline no. CG59. London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, Baldwin R, Burns A, Chew-Graham C. ‘Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowrick CF, Ring A, Humphris GM, Salmon P. Normalisation of unexplained symptoms by general practitioners: a functional typology. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(500):165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmon P, Peters S, Stanley I. Patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatisation disorders: qualitative analysis. BMJ. 1999;318(7180):372–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ring A, Dowrick CF, Humphris GM, Davies J, Salmon P. The somatising effect of clinical consultation: what patients and doctors say and do not say when patients present medically unexplained physical symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1505–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogden J, Branson R, Bryett A, et al. What’s in a name? An experimental study of patients’ views of the impact and function of a diagnosis. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Main CJ, Buchbinder R, Porcheret M, Foster N. Addressing patient beliefs and expectations in the consultation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(2):219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrne PS, Long PEL. Doctors Talking to Patients. London: HMSO; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong BN, Hooper H. Comparing clinical and lay accounts of the diagnosis and treatment of back pain. Sociol Health Illn. 2006;28(2): 203–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bedson J, McCarney R, Croft P. Labelling chronic illness in primary care: a good or a bad thing? Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(509):932–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005;365(9463):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman T. Using video-recorded consultations for research in primary care: advantages and limitations. Fam Pract. 2000;17(5): 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]