Abstract

Coordinated movement of large groups of cells is required for many biological processes, such as gastrulation and wound healing. During collective cell migration, cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesions must be integrated so that cells maintain strong interactions with neighboring cells and the underlying substratum. Initiation and maintenance of cadherin adhesions at cell-cell junctions and integrin-based cell-ECM adhesions require integration of mechanical cues, dynamic regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and input from specific signaling cascades, including Rho family GTPases. Here, we summarize recent advances made in understanding the interplay between these pathways at cadherin- and integrin-based adhesions during collective cell migration and highlight outstanding questions that remain in the field.

Introduction

The coordinated movement of groups of cells, termed collective cell migration, is critical for many biological processes at nearly all stages of life. In development, groups of cells move in a coordinated manner during gastrulation when the blastula is reorganized into a multilayer tissue comprised of the three germ layers [1,2]. During neurogenesis, neural crest cells migrate to distant regions of the embryo as loosely connected strands of cells [3,4]. Other forms of collective cell migration require coordinated movements of large sheets of cells, such as closing a wound following injury [5].

Collective cell migration is also prevalent in certain disease states, such as cancer. The classic view of cancer metastasis is that of single cells undergoing an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and adopting a migratory phenotype [6]. However, collective cell migration is also recognized as a well-established mode of metastasis for certain types of tumors, especially carcinomas [7].

Coordinated movement of large groups of cells is tightly regulated, as cells maintain strong, yet dynamic adhesions with both neighboring cells and the ECM. Cells within cohesive tissues have cadherin-based adhesions at cell-cell junctions [8] and integrin-based focal adhesions at cell-ECM contacts [9]. Cadherin- and integrin-based adhesions are large, multi-protein complexes that function as structural, mechanical, and signaling hubs whose functions must be integrated to coordinate cell migration and cell-cell adhesion [8,9]. The importance of “cadherin-integrin crosstalk” has been recognized for decades [10,11], yet only recently have advances been made in understanding the biophysical properties, biochemical signals and mechanisms that govern transitions between migration and cell-cell adhesion [12–14]. This review will highlight recent advances made in understanding force transmission, actin dynamics, and Rho GTPases at cadherin and integrin adhesions, and how signals arising from both adhesions are integrated during collective cell migration.

Biophysical properties of cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions

Both cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions are force-bearing structures that withstand and respond to picoNewton to nanoNewton forces from the surrounding environment (neighboring cells or the substratum) [15–17]. Focal adhesions grow in response to applied force [18], and traction stresses generated by focal adhesions are influenced by the rigidity of the substratum [19]. Cadherin adhesions are also mechanosensitive structures. Cadherins are under constitutive tension [16,17], and cadherin-based adhesions are reinforced upon force application [20–22]. Thus mechanical force regulates the size of both cadherin and integrin junctions [18,22].

Forces at cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions are intimately connected with each other. The amount of tension that develops at cell-cell junctions can be influenced by the composition, rigidity, and organization of the ECM [23–25]. For example, pairs of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells adhering to collagen I-coated polyacrylamide gels generate higher tension at cell-cell contacts compared to pairs of cells on a fibronectin-coated gel [23]. Substrate rigidity can also influence how integrins affect cadherin function. Using micropatterned substrates designed with islands of ECM surround by E-cadherin, Tsai et al demonstrated that MCF-7 cell adhesion to ECM inhibited formation of cadherin adhesions on rigid micropatterned substrates (5 MPa), while cadherin adhesions were still able to form when cells adhered to softer substrates (60 kPa) [25]. However, rigidity-dependent inhibition of cadherin adhesion is cell-type specific, or may be a hallmark of cancerous cells, as integrin adhesion on stiff substrates does not block cadherin adhesion in MDCK cells [25]. Another study, using ECM micropatterned in various geometries, demonstrated that ECM organization influences cell-cell contact positioning and generation of intra- and inter-cellular tension; cell-cell junctions formed away from ECM contacts are stabilized due to low intra- and inter-cellular force generation [24].

Cadherin-based adhesions also influence traction forces at cell-ECM contacts. In the absence of cadherin-based adhesions, a group of cells exerts traction stresses throughout the colony. However, when cadherin-mediated adhesion is induced, traction stresses at cell-ECM adhesions reorganize and become highly localized at the periphery of the colony [26•]. These observations raise the question: how are forces tightly regulated at specific cellular locations to maintain homeostasis? A model of cellular tensegrity suggests that a pre-stressed actin cytoskeleton could provide rapid and directed transmission of forces across the cell [27], and changes in actin dynamics could facilitate the reorganization of those forces.

Actin-associated proteins, such as vinculin, may facilitate force transduction at both adhesions. Vinculin is recruited to cadherin adhesions in a force-dependent manner and is required for mechanical reinforcement of the adhesion [20,21]. Furthermore, the interaction between vinculin and the cadherin-catenin complex is stabilized by a tension-induced conformational change in α-catenin that exposes a vinculin binding site [28]. Single molecule studies have shown that binding of vinculin to α-catenin dramatically increases the lifetime of an unfolded conformation of α-catenin [29•], and that force is required for strong binding between F-actin and α-catenin in the cadherin complex [30••]. Force-dependent recruitment of vinculin to cell-cell junctions likely stabilizes the junction by increasing the lifetime of the interaction between cadherin adhesions and the actin cytoskeleton, thereby priming the cadherin adhesion as a mechanosensitive structure. In addition, vinculin has a well-documented role in anchoring the actin cytoskeleton to focal adhesions; for example, it associates with the focal adhesion protein talin in a force-dependent manner [31,32], and strengthens adhesions by increasing the interaction between integrin adhesions and the actin cytoskeleton [31,33].

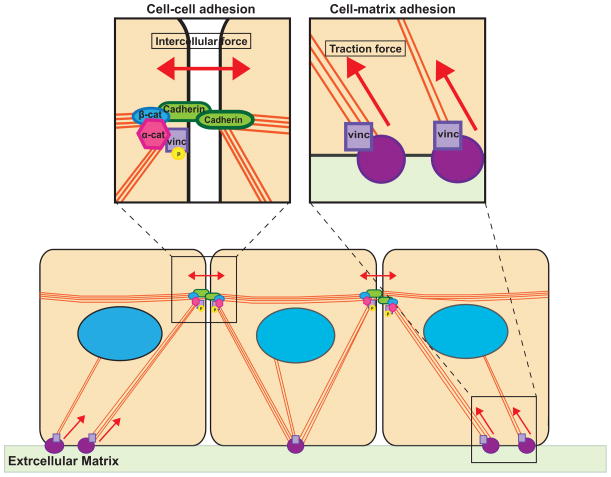

In light of evidence indicating that vinculin plays a critical role in force transduction at both adhesive structures, it becomes apparent the subcellular localization of the protein must be finely regulated based on changes in cell mechanics. Recent work demonstrated that mechanical tension on E-cadherin activates Abl kinase resulting in phosphorylation of vinculin and its preferential recruitment to cell-cell junctions, rather focal adhesions [34••]. These data indicate that the actin cytoskeleton acts as a global transducer of mechanical force, and that specific signaling cascades and post-translational modifications on mechanosensitive proteins (such as vinculin) fine-tune force transduction at specific subcellular locations to maintain mechanical homeostasis in multicellular tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Integration of forces at cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions.

In multicellular tissues, mechanical forces are balanced between cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion, and tension on either structure reinforces the adhesion. At cell-cell junctions, mechanical force strengthens the interaction between the cadherin-catenin complex and the actin cytoskeleton. Similarly, force on cell-ECM adhesions, results in recruitment of actin binding proteins that reinforce association with actin filaments. Some key actin binding proteins, such as vinculin, are critical for force transduction at both adhesive structures, and the subcellular localization of such proteins must be regulated to fine-tune force balance at specific adhesions.

Actin dynamics and signaling pathways at cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions

The formation and maintenance of cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions require dynamic changes in the actin cytoskeleton. During cell migration, directed actin polymerization at the leading edge drives lamellipodial protrusions forward, and actomyosin tension generates traction stresses and contractility that facilitate tail retraction [35]. Similarly, cell-cell adhesions require dynamic regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and photobleaching studies have indicated that a large fraction of actin filaments at cell-cell contacts is highly dynamic [36,37]. Given that the actin cytoskeleton is highly dynamic at both types of adhesions, actin dynamics must be tightly regulated in multicellular groups.

The roles of specific actin regulators in collective cell migration remain largely unexplored. However, a recent study revealed that the actin regulatory protein lamellipodin (Lpd) facilitates collective cell migration by influencing the activity of the Scar/WAVE complex [38••]. Lpd directly interacts with Rac and the Scar/WAVE complex to promote lamellipodia extension and cell migration in fibroblasts in culture, but also has clear roles in collective cell migration in vivo. Knockdown of Lpd in Xenopus or of the Drosophila ortholog of Lpd (Pico) impairs neural crest cell migration and oocyte border cell migration, respectively [38••]. The mechanisms of how Lpd (and other actin regulators) integrate actin dynamics at cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions during collective cell migration remain largely unexplored. However, it is possible that upstream signaling molecules (such as Rho family GTPases) may influence the subcellular localization and activity of actin regulatory proteins to fine-tune the strength of cell-cell or cell-ECM adhesions.

Rho family GTPases are master regulators of the actin cytoskeleton, and play key roles in assembly and maintenance of cell-cell contacts and cell migration. Initial studies revealed that cell-cell adhesion results in decreased RhoA activity and increased Rac and Cdc42 activities [39–41], and later work indicated that precise spatiotemporal control of GTPase activity is critical for development of mature cell-cell contacts [42]. Maintenance of mature cell-cell contacts requires basal levels of Rho GTPase signaling, which support dynamic remodeling of the junction via recycling of cadherins and local actin polymerization [43]. Similarly, cell migration requires dynamic changes in GTPase activity. Cdc42, Rac, and RhoA are active at the leading edge of a migrating cell and play distinct roles in cytoskeletal regulation. Cdc42 is classically known to initiate formation of filopodia which are important for determining migration direction but can also indirectly activate Rac [44]. Rac promotes lamellipodia formation and branched actin organization via its effectors, WAVE and Arp2/3, and RhoA activity at the leading edge has been proposed to initiate actin polymerization at the leading edge through regulation of the Diaphanous family of formins [44,45]. RhoA activity at the lateral and rear edges of the cell is also required for generation of actomyosin contractility [45,46]. Given Since Rho family that GTPases are required for cadherin and integrin function, their activity must be regulated to transitions between cell-cell adhesion and cell migration.

The activities of Rho GTPases at cadherin or integrin-based adhesions could be regulated by the subcellular localization of: 1) the GTPase itself (including its regulation through cytosolic sequestration by RhoGDIs), and 2) guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) that locally regulate GTPase activity. In line with the second hypothesis, many GEFs and GAPs are required for both cell-cell adhesion and cell-cell migration, and recent studies have identified specific roles for GEFs/GAPs in regulating adhesive crosstalk. For example, the Rac GEF Tiam1 promotes either cell-cell adhesion or migration in an ECM-dependent manner [47]. Tiam1 localizes to lamellipodia and promotes cell migration in Ras-transformed MDCK-f3 fibroblast-like cells plated on collagen. In contrast, Tiam1 is highly localized to cell-cell adhesions and inhibits migration in MDCK-f3 cells adhering to fibronectin or laminin by restoring cadherin-dependent adhesion. Thus, dynamic spatial regulation of Tiam1 influences Rac activity at distinct cellular sites to promote either cell-cell adhesion or cell migration. The molecular mechanism involved in the spatial regulation of Tiam1 is not well understood, although PI3-kinase (PI3K) activity is important for Tiam1 activity at both cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions [47]. Another example of crosstalk can be found in p190B RhoGAP (p190B). p190B associates with p120-catenin at adherens junctions and influences RhoA activity at cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions in T47D breast epithelial cells cultured in a 3D collagen gel [48•]. When T47D epithelial cells are grown in a 3D collagen gel attached to the substrate, the matrix is able to resist cell-generated force, as attachment to the substrate restrains the matrix and permits development of isometric tension. However, if the collagen gel is released from the substrate, the matrix cannot resist force applied by cells, and the gel contracts due to cell-generated tension. In compliant (floating) gels, p190B associates with p120-catenin and inhibits RhoA at cell-cell contacts thereby changing the balance of RhoA activity at cell-cell vs. cell-ECM contacts. In contrast, when T47D cells are grown in a stiff (attached) 3D collagen gel, p190B and p120-catenin dissociate from cadherin, which releases a pool of previously inactive RhoA from cell-cell contacts and results in enhanced RhoA activity at cell-ECM contacts. Thus, p190B holds RhoA inactive at junctions in cells within soft matrices, and dissociation of the GAP from cell-cell contacts promotes recruitment of RhoA to cell-ECM contacts within stiff matrices. While it is possible that a Rho GEF may be spatially sequestered at cell-matrix contacts to permit local activation of the RhoA at that site in stiff matrices, a specific GEF has not yet been shown to facilitate RhoA activation in this pathway.

While we highlight Tiam1 and p190B as regulators of cadherin-integrin crosstalk, many other regulators of GTPase activity are involved. For example, The Dock-Elmo complex (a bipartite GEF with activity for Rac and Cdc42) was originally identified to play a role in integrin-based cell spreading and migration [49,50]. However, a recent screen to identify proteins required for cadherin-based adhesion (in the absence of integrin-based adhesions) identified Elmo2 [51]. A follow-up study revealed a Dock-Elmo complex, consisting of Dock1 and Elmo2, that locally regulates actin dynamics and Rho GTPase during the initiation of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion [52]. In addition, numerous GEFs and GAPs have been identified as components of both cadherin and integrin adhesomes [53,54] and are also prime candidates to be studied in the future. Furthermore, while we have focused on the Rho family of GTPases and regulators of GTPase activity as mediators of cadherin-integrin crosstalk, many other kinases and GTPases (ex: Src, FAK, Rap1) also mediate signaling between the two adhesion sites and have been described in detail elsewhere [12,55–58].

Given that some of the same signaling molecules are required for both cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions, the following questions arise: how do cells integrate signaling arising from both types of adhesions, and how are these signals coordinated during complex cellular behaviors, such as collective cell migration? Recently, reductionist approaches (microfabricated substrates or biophysical assays) have been used to dissect the crosstalk between cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions [25,59]. From these studies, it is apparent that integrins can influence cadherin adhesion organization and function, and vice versa. Microfabricated substrates patterned with collagen IV and the extracellular domain of E-cadherin revealed that cadherin-mediated adhesion suppresses integrin-based lamellipodia activity in a dose-dependent manner (as the concentration of E-cadherin increases, the effect on integrin-based membrane dynamics increases) [59]. Down-regulation of integrin-based activity also occurred when desmosomal cadherin adhesion was engaged using a similar assay [60]. These findings may provide insight into a potential mechanism of cadherin-integrin adhesion crosstalk. For example, an increase in cadherin engagement during cell-cell contact formation may serve as a signal to titrate signaling proteins, which are normally shared between cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions, to cell-cell junctions. This would limit the availability of these proteins to act on effectors at integrin-based adhesions and diminish their capacity to promote cell migration. Microfabricated surfaces that allow for fine control of spatial organization, concentration, and identity of specific adhesion proteins provide excellent platforms to further elucidate molecular mechanisms of adhesive crosstalk.

Integration of biophysical and biochemical signals during collective cell migration

During collective cell migration, signaling cascades arising from cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions must be spatially regulated and coordinated, and recent studies have started to address how these signals are integrated in more complex biological processes. For example, integrins, Rac, and PI3K are upregulated in leader cells during collective cell migration [61]; N-cadherin spatially polarizes these signaling cascades to the free (non-contacting) edge of migrating cells by locally excluding α5 integrin at cell-cell junctions, which decreases integrin-dependent PI3K and Rac activity at those sites [62•]. In a separate study, paramagnetic beads coated with the extracellular domain of C-cadherin (the predominant cadherin in Xenopus embryos) were used to apply force on cadherin adhesions in isolated, migrating mesendoderm cells. This led to recruitment of plakoglobin and intermediate filaments to the cadherin adhesion, and polarized protrusive activity at the opposite side of the cell, which resulted in cells migrating away from the direction of the applied force [63]. Further studies are required to determine whether cadherins provide spatial cues for additional signaling cascades.

Recent advances in microscopy have enabled calculations of intercellular forces during collective cell migration. Monolayer stress microscopy, which permits the measurement of local stresses within a monolayer, revealed a large heterogeneity in intercellular forces within a monolayer of migrating MDCK epithelial cells, but strong local correlations in groups of cells. Perturbation of cell-cell contacts by calcium chelation or addition of an E-cadherin function-blocking antibody disrupted local intercellular force correlations and coordinated migration of monolayer [64]. These results indicate that E-cadherin is specifically required for coordinating cues that govern coordinated movement of epithelial cells. A follow-up study systematically tested the contribution of individual cadherin isoforms (E-cadherin, P-cadherin, and N-cadherin) in monolayer force transmission in MCF10A cells revealed an unexpected result. P-cadherin is responsible for intercellular force transmission, while E-cadherin influences the rate of intercellular force generation [65••]. Interestingly, in the absence of E-cadherin, P-cadherin also triggers mechanotransduction events and undergoes vinculin-dependent reinforcement. These results indicate the E-cadherin and P-cadherin share a similar mechanotransduction pathway, although E-cadherin is dominant when both isoforms are present. These results also highlight the importance of multiple cadherin isoforms in monolayer force transmission.

Rho family GTPase activities have also been examined in epithelial monolayers. In a wound healing assay, rat liver epithelial (IAR-2) cells migrate to close a wound using finger-like projections as specific cells at the edge of the wound take on a ‘leader cell’ identity [66]. In a separate study utilizing micro-posts to measure traction forces between cells and the substratum, Reffay et al reported that the highest traction stresses in MDCK cells are exerted by leader cells at the tips of migration fingers. High traction stresses also co-localized with increase RhoA activity and phospho-myosin light chain, and hence active myosin II [67]. Strikingly, the traction stress pattern of the entire monolayer was reminiscent of force distribution found within a single cell [67••], indicating that the entire monolayer was acting as a mechanical entity. How are force and signaling cascades coordinated throughout a multicellular structure? As noted above, E-cadherin is involved in coordinating local intercellular forces throughout a monolayer [64], and other studies indicate that E-cadherin engagement regulates RhoA signaling at cell junctions [68]. An attractive hypothesis, therefore, is that E-cadherin engagement is required to coordinate traction stresses and RhoA activity in a migrating monolayer, but further experiments need to be performed to specifically test this idea.

The hypothesis that cadherins play a central role coordinating changes in mechanical forces and Rac signaling during collective cell migration is supported by recent studies of border cell migration in the Drosophila oocyte [69••]. A FRET-based biosensor, which measures mechanical tension in the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin, revealed asymmetric force distribution across E-cadherin in migrating border cells, such that E-cadherin at the front of the cell cluster was under more tension than E-cadherin in cells at the rear of the cluster. Force across E-cadherin initiated a mechanical feed forward loop that amplified and polarized Rac signaling to the front of the cell cluster to promote coordinated migration [69••]. More recent work has identified a mechanotransduction pathway involving Rac and the tumor suppressor protein merlin that influences collective cell migration in MDCK cells [70]. Initial polarization of Rac activity and lamellipodia extension in leader cells increases intercellular stress at the leader cell-follower cell junction and results in force-induced translocation of merlin from junctions to the cytoplasm; polarized Rac activation and formation of a cryptic lamellipod in the follower cell required merlin translocation [70••]. Thus, force-dependent regulation of merlin localization and Rac activity enables long-range coordination of mechanical forces and GTPase activity in a migrating monolayer. While the role of cadherin was not specifically tested in force transmission in this system, the finding that E-cadherin is required for Rac polarization in the Drosophila oocyte model system indicates that cadherin may be required for force-dependent translocation of merlin from cell-cell contacts to the cytoplasm [69].

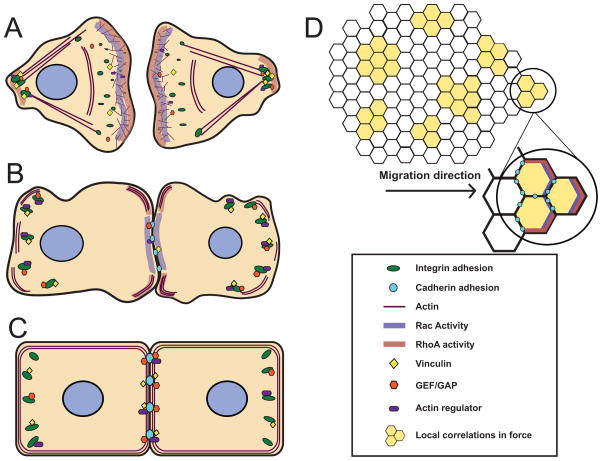

Bringing all of these data together, we propose a model whereby cadherins play multiples roles in coordinating collective cell migration. Upon cell-cell contact, cadherins on neighboring cells are engaged, and organized cell-cell adhesions begin to assemble. Integrin-based traction forces at the substratum are then reorganized (reduced) as tension is transferred to cell-cell adhesions and intercellular forces increase, which results in further growth and reinforcement of cadherin-based adhesions. As the size of cell-cell adhesions increases and become more prominent, we hypothesize that proteins required for strong cell-cell adhesion (vinculin, Rho family GTPases, regulators of actin dynamics) are titrated to the growing cadherin adhesions. The full establishment of cell-cell adhesions results in a balance of both forces and localization of key structural and signaling proteins between cadherin- and integrin-based adhesions that coordinate collective cell migration (Figure 2). While the titration of signaling molecules is one mechanism for integrating signals between cadherin- and integrin-based adhesions during collective cell migration, other mechanisms also contribute to adhesive crosstalk, as multiple studies have also highlighted the importance of force transmission via a tensile actin cytoskeleton and precise spatiotemporal activation of specific signaling cascades during collective cell migration [64,67,70].

Figure 2. Coordination of cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions in multicellular groups and collective cell migration.

A) In individual migrating cells, GTPases at the leading edge of the lamellipodia drive actin polymerization and the formation of nascent focal contacts. RhoA activity promotes stress fiber formation, contractility and tail retraction. B) During formation of a naïve cell-cell contact, small cadherin adhesions form and begin recruiting regulators of GTPases and actin dynamics. Focal adhesions reorganize as force is transferred to the growing cell-cell adhesion. C) As cadherin adhesions grow in size and strength, we hypothesize that key signaling molecules (such as GAPs and GEFs) and regulators of actin dynamics are titrated to cell-cell adhesions. Cellular forces are balanced between cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions to reach mechanical homeostasis. D) During collective cell migration of large groups of cells, cadherin adhesions enable local correlations in intercellular forces, and Rho GTPase activity is spatially regulated to facilitate coordinated movement of the monolayer.

Conclusions

Collective cell migration is central to nearly all stages of life and contributes to disease states, such as cancer metastasis. A comprehensive understanding of mechanisms of collective cell migration is required to understand basic biological processes during development and may also reveal new avenues for cancer therapies. Recent work has indicated that the coordinated organization of traction and intercellular forces cadherin- and integrin-based adhesion complexes is required for coordinated movement of large groups of cells, and spatiotemporal regulation of Rho family GTPases and actin dynamics are required for collective cell migration. However, further studies are required to understand how these pathways are integrated between cadherin- and integrin-based adhesions in collective cell migration.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Nelson lab for critical reading of this manuscript. CC was supported by PHS grant T32 CA09151 awarded by the National Cancer Institute and work in the Nelson laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM035527).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McMahon A, Supatto W, Fraser SE, Stathopoulos A. Dynamic analyses of Drosophila gastrulation provide insights into collective cell migration. Science. 2008;322:1546–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.1167094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weijer CJ. Collective cell migration in development. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3215–3223. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duband JL, Monier F, Delannet M, Newgreen D. Epithelium-mesenchyme transition during neural crest development. Acta Anat (Basel) 1995;154:63–78. doi: 10.1159/000147752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theveneau E, Mayor R. Collective cell migration of the cephalic neural crest: the art of integrating information. Genesis. 2011;49:164–176. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedl P, Noble PB, Walton PA, Laird DW, Chauvin PJ, Tabah RJ, Black M, Zanker KS. Migration of coordinated cell clusters in mesenchymal and epithelial cancer explants in vitro. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4557–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pokutta S, Weis WI. Structure and mechanism of cadherins and catenins in cell-cell contacts. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamir E, Geiger B. Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3583–3590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abercrombie M, Heaysman JE. Observations on the social behaviour of cells in tissue culture. I. Speed of movement of chick heart fibroblasts in relation to their mutual contacts. Exp Cell Res. 1953;5:111–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(53)90098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abercrombie M, Heaysman JE. Observations on the social behaviour of cells in tissue culture. II. Monolayering of fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1954;6:293–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(54)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canel M, Serrels A, Frame MC, Brunton VG. E-cadherin-integrin crosstalk in cancer invasion and metastasis. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:393–401. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMali KA, Sun X, Bui GA. Force transmission at cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7706–7717. doi: 10.1021/bi501181p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber GF, Bjerke MA, DeSimone DW. Integrins and cadherins join forces to form adhesive networks. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1183–1193. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grashoff C, Hoffman BD, Brenner MD, Zhou R, Parsons M, Yang MT, McLean MA, Sligar SG, Chen CS, Ha T, et al. Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature. 2010;466:263–266. doi: 10.1038/nature09198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borghi N, Sorokina M, Shcherbakova OG, Weis WI, Pruitt BL, Nelson WJ, Dunn AR. E-cadherin is under constitutive actomyosin-generated tension that is increased at cell-cell contacts upon externally applied stretch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12568–12573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204390109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway DE, Breckenridge MT, Hinde E, Gratton E, Chen CS, Schwartz MA. Fluid shear stress on endothelial cells modulates mechanical tension across VE-cadherin and PECAM-1. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trichet L, Le Digabel J, Hawkins RJ, Vedula SR, Gupta M, Ribrault C, Hersen P, Voituriez R, Ladoux B. Evidence of a large-scale mechanosensing mechanism for cellular adaptation to substrate stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6933–6938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117810109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.le Duc Q, Shi Q, Blonk I, Sonnenberg A, Wang N, Leckband D, de Rooij J. Vinculin potentiates E-cadherin mechanosensing and is recruited to actin-anchored sites within adherens junctions in a myosin II-dependent manner. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:1107–1115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huveneers S, Oldenburg J, Spanjaard E, van der Krogt G, Grigoriev I, Akhmanova A, Rehmann H, de Rooij J. Vinculin associates with endothelial VE-cadherin junctions to control force-dependent remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:641–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Tan JL, Cohen DM, Yang MT, Sniadecki NJ, Ruiz SA, Nelson CM, Chen CS. Mechanical tugging force regulates the size of cell-cell junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9944–9949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914547107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruthamuthu V, Sabass B, Schwarz US, Gardel ML. Cell-ECM traction force modulates endogenous tension at cell-cell contacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4708–4713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011123108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng Q, Duchemin-Pelletier E, Deshiere A, Balland M, Guillou H, Filhol O, Thery M. Spatial organization of the extracellular matrix regulates cell-cell junction positioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1506–1511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106377109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai J, Kam L. Rigidity-dependent cross talk between integrin and cadherin signaling. Biophys J. 2009;96:L39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Mertz AF, Che Y, Banerjee S, Goldstein JM, Rosowski KA, Revilla SF, Niessen CM, Marchetti MC, Dufresne ER, Horsley V. Cadherin-based intercellular adhesions organize epithelial cell-matrix traction forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:842–847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217279110. This paper demonstrates that cadherin engagement influences traction forces at integrin-based adhesions and forces are reorganized to the periphery of the colony of cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingber DE, Wang N, Stamenovic D. Tensegrity, cellular biophysics, and the mechanics of living systems. Rep Prog Phys. 2014;77:046603. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/77/4/046603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonemura S, Wada Y, Watanabe T, Nagafuchi A, Shibata M. alpha-Catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:533–542. doi: 10.1038/ncb2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Yao M, Qiu W, Liu R, Efremov AK, Cong P, Seddiki R, Payre M, Lim CT, Ladoux B, Mege RM, et al. Force-dependent conformational switch of alpha-catenin controls vinculin binding. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4525. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5525. This study revealed that alpha-catenin undergoes a force-dependent conformational change that promotes association with vinculin. The alpha-catenin/vinculin interaction is required for proper force transduction at cell-cell adhesions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Buckley CD, Tan J, Anderson KL, Hanein D, Volkmann N, Weis WI, Nelson WJ, Dunn AR. Cell adhesion. The minimal cadherin-catenin complex binds to actin filaments under force. Science. 2014;346:1254211. doi: 10.1126/science.1254211. Using an optical trap, the authors demonstrate that mechanical force strengthens the interaction between the actin cytoskeleton and the cadherin-catenin complex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirata H, Tatsumi H, Lim CT, Sokabe M. Force-dependent vinculin binding to talin in live cells: a crucial step in anchoring the actin cytoskeleton to focal adhesions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C607–620. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.del Rio A, Perez-Jimenez R, Liu R, Roca-Cusachs P, Fernandez JM, Sheetz MP. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galbraith CG, Yamada KM, Sheetz MP. The relationship between force and focal complex development. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Bays JL, Peng X, Tolbert CE, Guilluy C, Angell AE, Pan Y, Superfine R, Burridge K, DeMali KA. Vinculin phosphorylation differentially regulates mechanotransduction at cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:251–263. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201309092. In this study, the authors demonstrate that the subcellular localization of vinculin is influenced by the phosphorylation status of the protein. Phosphorylated vinculin is preferentially localized to cell-cell adhesions and is required for force-dependent reinforcement of the E-cadherin adhesions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rottner K, Stradal TE. Actin dynamics and turnover in cell motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada S, Pokutta S, Drees F, Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell. 2005;123:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovacs EM, Verma S, Ali RG, Ratheesh A, Hamilton NA, Akhmanova A, Yap AS. N-WASP regulates the epithelial junctional actin cytoskeleton through a non-canonical post-nucleation pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:934–943. doi: 10.1038/ncb2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38••.Law AL, Vehlow A, Kotini M, Dodgson L, Soong D, Theveneau E, Bodo C, Taylor E, Navarro C, Perera U, et al. Lamellipodin and the Scar/WAVE complex cooperate to promote cell migration in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:673–689. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304051. In this paper, an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that control actin dynamics in single cell and collective cell migration was identified. Lamellipodin and the Scar/WAVE complex promote cell migration in single cells in vitro and are required for collective cell migration in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braga VM, Machesky LM, Hall A, Hotchin NA. The small GTPases Rho and Rac are required for the establishment of cadherin-dependent cell-cell contacts. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1421–1431. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noren NK, Niessen CM, Gumbiner BM, Burridge K. Cadherin engagement regulates Rho family GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33305–33308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagawa M, Fukata M, Yamaga M, Itoh N, Kaibuchi K. Recruitment and activation of Rac1 by the formation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion sites. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada S, Nelson WJ. Localized zones of Rho and Rac activities drive initiation and expansion of epithelial cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:517–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratheesh A, Yap AS. A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nrm3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zegers MM, Friedl P. Rho GTPases in collective cell migration. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e28997. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.28997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machacek M, Hodgson L, Welch C, Elliott H, Pertz O, Nalbant P, Abell A, Johnson GL, Hahn KM, Danuser G. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature. 2009;461:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pertz O, Hodgson L, Klemke RL, Hahn KM. Spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity in migrating cells. Nature. 2006;440:1069–1072. doi: 10.1038/nature04665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sander EE, van Delft S, ten Klooster JP, Reid T, van der Kammen RA, Michiels F, Collard JG. Matrix-dependent Tiam1/Rac signaling in epithelial cells promotes either cell-cell adhesion or cell migration and is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1385–1398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Ponik SM, Trier SM, Wozniak MA, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. RhoA is down-regulated at cell-cell contacts via p190RhoGAP-B in response to tensional homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1688–1699. S1681–1683. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-05-0386. Using a 3D collagen gel model of ductal morphogenesis, the authors demonstrate that 190B downregulates RhoA activity at cell-cell contacts and influences tensional homeostasis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katoh H, Negishi M. RhoG activates Rac1 by direct interaction with the Dock180-binding protein Elmo. Nature. 2003;424:461–464. doi: 10.1038/nature01817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimsley CM, Kinchen JM, Tosello-Trampont AC, Brugnera E, Haney LB, Lu M, Chen Q, Klingele D, Hengartner MO, Ravichandran KS. Dock180 and ELMO1 proteins cooperate to promote evolutionarily conserved Rac-dependent cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6087–6097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toret CP, D’Ambrosio MV, Vale RD, Simon MA, Nelson WJ. A genome-wide screen identifies conserved protein hubs required for cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:265–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toret CP, Collins C, Nelson WJ. An Elmo-Dock complex locally controls Rho GTPases and actin remodeling during cadherin-mediated adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:577–587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaidel-Bar R. Cadherin adhesome at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:373–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaidel-Bar R, Itzkovitz S, Ma’ayan A, Iyengar R, Geiger B. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:858–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb0807-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Avizienyte E, Wyke AW, Jones RJ, McLean GW, Westhoff MA, Brunton VG, Frame MC. Src-induced de-regulation of E-cadherin in colon cancer cells requires integrin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:632–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen XL, Nam JO, Jean C, Lawson C, Walsh CT, Goka E, Lim ST, Tomar A, Tancioni I, Uryu S, et al. VEGF-induced vascular permeability is mediated by FAK. Dev Cell. 2012;22:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Retta SF, Balzac F, Avolio M. Rap1: a turnabout for the crosstalk between cadherins and integrins. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez-Rico C, Pincet F, Thiery JP, Dufour S. Integrins stimulate E-cadherin-mediated intercellular adhesion by regulating Src-kinase activation and actomyosin contractility. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:712–722. doi: 10.1242/jcs.047878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borghi N, Lowndes M, Maruthamuthu V, Gardel ML, Nelson WJ. Regulation of cell motile behavior by crosstalk between cadherin- and integrin-mediated adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002662107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowndes M, Rakshit S, Shafraz O, Borghi N, Harmon RM, Green KJ, Sivasankar S, Nelson WJ. Different roles of cadherins in the assembly and structural integrity of the desmosome complex. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2339–2350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.146316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamaguchi N, Mizutani T, Kawabata K, Haga H. Leader cells regulate collective cell migration via Rac activation in the downstream signaling of integrin beta1 and PI3K. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7656. doi: 10.1038/srep07656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62•.Ouyang M, Lu S, Kim T, Chen CE, Seong J, Leckband DE, Wang F, Reynolds AB, Schwartz MA, Wang Y. N-cadherin regulates spatially polarized signals through distinct p120ctn and beta-catenin-dependent signalling pathways. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1589. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2560. In this paper, the authors demonstrate that N-cadherin spatially regulates PI3K and Rac activity by locally excluding integrins from sites of cell-cell contact. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber GF, Bjerke MA, DeSimone DW. A mechanoresponsive cadherin-keratin complex directs polarized protrusive behavior and collective cell migration. Dev Cell. 2012;22:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tambe DT, Hardin CC, Angelini TE, Rajendran K, Park CY, Serra-Picamal X, Zhou EH, Zaman MH, Butler JP, Weitz DA, et al. Collective cell guidance by cooperative intercellular forces. Nat Mater. 2011;10:469–475. doi: 10.1038/nmat3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65••.Bazellieres E, Conte V, Elosegui-Artola A, Serra-Picamal X, Bintanel-Morcillo M, Roca-Cusachs P, Munoz JJ, Sales-Pardo M, Guimera R, Trepat X. Control of cell-cell forces and collective cell dynamics by the intercellular adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:409–420. doi: 10.1038/ncb3135. The authors demonstate that, in MCF10A epithelial cells, P-cadherin influences force transmission throughout a monolayer, while E-cadherin determines the rate of tension build-up. This study highlights the importance of multiple cadherin isoforms in mechanical homeostasis in multicellular structures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Omelchenko T, Vasiliev JM, Gelfand IM, Feder HH, Bonder EM. Rho-dependent formation of epithelial “leader” cells during wound healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10788–10793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834401100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Reffay M, Parrini MC, Cochet-Escartin O, Ladoux B, Buguin A, Coscoy S, Amblard F, Camonis J, Silberzan P. Interplay of RhoA and mechanical forces in collective cell migration driven by leader cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:217–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2917. In this paper, the authors demonstrate that RhoA activitity is spatially regulated in a migrating monoayer of cells and regions of high RhoA activity correlate with areas of high traction stresses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Priya R, Yap AS, Gomez GA. E-cadherin supports steady-state Rho signaling at the epithelial zonula adherens. Differentiation. 2013;86:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69••.Cai D, Chen SC, Prasad M, He L, Wang X, Choesmel-Cadamuro V, Sawyer JK, Danuser G, Montell DJ. Mechanical feedback through E-cadherin promotes direction sensing during collective cell migration. Cell. 2014;157:1146–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.045. Using the Drosophila oocyte as a model of collective cell migration, the author demonstrate that tension across E-cadherin polarizes and amplifies Rac activity in the migrating cluster of cells. Thus, E-cadherin functions as a instructive cue for signaling cascades involved in collective cell migration. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70••.Das T, Safferling K, Rausch S, Grabe N, Boehm H, Spatz JP. A molecular mechanotransduction pathway regulates collective migration of epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:276–287. doi: 10.1038/ncb3115. This study identifies a mechanotransduction pathway involving the tumor suppressor protein Merlin and Rac1 that influences force tranmission, lamellipodial dynamics, and collective cell migration in MDCK monolayers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]