Abstract

Secreted Wnt proteins play pivotal roles in development, including regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, progenitor maintenance and tissue patterning. The transmembrane protein Wntless (Wls) is necessary for secretion of most Wnts and essential for effective Wnt signaling. During a mutagenesis screen to identify genes important for development of the habenular nuclei in the dorsal forebrain, we isolated a mutation in the sole wls gene of zebrafish and confirmed its identity with a second, independent allele. Early embryonic development appears normal in homozygous wls mutants, but they later lack the ventral habenular nuclei, form smaller dorsal habenulae and otic vesicles, have truncated jaw and fin cartilages and lack swim bladders. Activation of a reporter for β-catenin-dependent transcription is decreased in wls mutants, indicative of impaired signaling by the canonical Wnt pathway, and expression of Wnt-responsive genes is reduced in the dorsal diencephalon. Wnt signaling was previously implicated in patterning of the zebrafish brain and in the generation of left–right (L–R) differences between the bilaterally paired dorsal habenular nuclei. Outside of the epithalamic region, development of the brain is largely normal in wls mutants and, despite their reduced size, the dorsal habenulae retain L–R asymmetry. We find that homozygous wls mutants show a reduction in two cell populations that contribute to the presumptive dorsal habenulae. The results support distinct temporal requirements for Wls in habenular development and reveal a new role for Wnt signaling in the regulation of dorsal habenular progenitors.

Keywords: Wnt signaling, Diencephalon, dbx1b, cxcr4b, Left-right asymmetry, Zebrafish

1. Introduction

The habenulae are bilaterally paired nuclei in the epithalamus that connect the limbic forebrain to the mid- and hind-brain. In mammals, the habenulae consist of medial and lateral nuclei, which have been implicated in a wide variety of behaviors including anxiety, sleep and reward (Aizawa, 2013; Hikosaka, 2010; Viswanath et al., 2014) and in conditions such as addiction, bipolar disorder and depression (Ranft et al., 2010; Savitz et al., 2011; Viswanath et al., 2014). Despite their functional importance, little is known about the development of the habenular nuclei.

Recently, the zebrafish has emerged as a valuable model to study habenular development. Zebrafish possess dorsal (dHb) and ventral (vHb) habenular nuclei, equivalent to the medial and lateral habenula of mammals, respectively (Aizawa et al., 2011). A recent study demonstrated an essential role for Wnt signaling in formation of the ventral habenulae (Beretta et al., 2013). Wnt signaling is also thought to underlie the prominent left–right (L–R) differences in the organization, gene expression, and connectivity of the dorsal nuclei. A mutation in axin1, which encodes a negative regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, causes both dorsal habenulae to adopt a right habenular identity as defined by gene expression and axonal targeting (Carl et al., 2007). Conversely, a mutation in tcf7l2, a Wnt-dependent transcriptional activator, results in the opposite phenotype, with both habenulae displaying features characteristic of the left nucleus (Hüsken et al., 2014). These findings suggest that the level of canonical Wnt signaling is a critical factor in the formation of habenular L–R differences. Although canonical Wnt signaling is essential for development of the ventral nuclei and for L–R asymmetry of the dorsal nuclei, the precise Wnts that mediate these functions and their cells of origin are unknown.

For secretion and effective signaling, Wnt proteins require a lipid modification that renders them hydrophobic and insoluble (Ke et al., 2013; Takada et al., 2006). The chaperone protein required for Wnt secretion is Wntless (Wls) (Banziger et al., 2006; Bartscherer et al., 2006; Goodman et al., 2006), a transmembrane protein that hides the lipid modification in a lipocalin fold and escorts the Wnt protein through the secretory pathway to the cell membrane (Das et al., 2012; Willert and Nusse, 2012). At the cell membrane, the Wnt is released from Wls, which is then recycled back to the endoplasmic reticulum via the Golgi to participate in further rounds of Wnt trafficking (Franch-Marro et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2014). It is currently thought that Wls is required for secretion of almost all Wnts and, therefore, necessary for canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Coudreuse and Korswagen, 2007; Najdi et al., 2012, Port and Basler, 2010). This is supported by the severe, early phenotypes of wls homozygous mutant mouse embryos and maternal zygotic Drosphila mutants (Banziger et al., 2006; Bartscherer et al., 2006; Carpenter et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2009; Goodman et al., 2006).

In the course of a mutagenesis screen to identify genes that control habenular development, we isolated a mutation in the zebrafish homolog of wls. In homozygous mutant embryos, the dorsal habenulae are reduced in size and the ventral habenulae are absent, whereas other regions of the brain appear unaffected. Surprisingly, the dorsal habenulae retain their L–R differences, suggesting that maternally provided Wls fulfills this requirement for Wnt signaling or that generation of habenular asymmetry is a Wls-independent process. However, early signaling is not sufficient to regulate habenular precursor cell populations, which are reduced in number in wls mutants. Our findings suggest that there are three distinct roles for Wnt signaling in habenular development, an early requirement for L–R asymmetry and later functions in the specification of the ventral habenulae and in the regulation of dorsal habenular precursors.

2. Results

2.1. Recovery of mutations in the zebrafish wntless gene

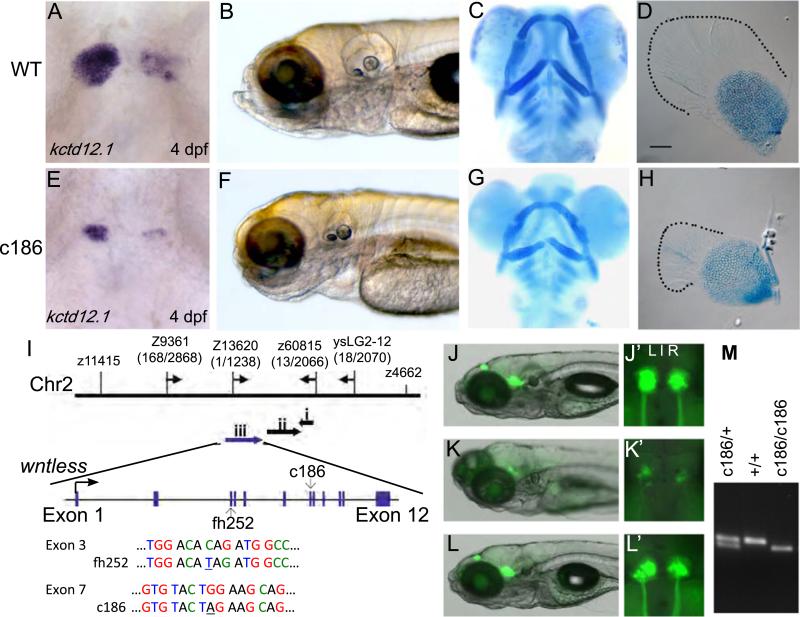

The c186 mutation was discovered in a mutagenesis screen to identify genes involved in the development and/or L–R asymmetry of the zebrafish habenular nuclei, as determined by altered expression of the potassium channel tetramerisation domain containing 12.1 gene (kctd 12.1, formerly known as leftover; Gamse et al., 2003). Homozygous mutants have a significantly reduced domain of kctd12.1 expression compared to wild type (WT) siblings, indicative of smaller dorsal habenular nuclei. However, the L–R difference in the distribution of kctd12.1 transcripts is preserved (Fig. 1A, E). During early embryonic development c186 mutants are morphologically indistinguishable from their WT siblings (data not shown), but by 4 days post-fertilization (dpf) they exhibit notable defects such as smaller otic vesicles, pectoral fins and jaw cartilages (Fig. 1B–D, F–H). The mutants fail to develop swim bladders and die by approximately 12 dpf.

Fig. 1.

Isolation of mutant zebrafish wls alleles. (A–D) WT and (E–H) c186 homozygous mutants. (A, E) The c186 mutation was isolated through an RNA in situ hybridization screen using the asymmetrically expressed kctd12.1 gene. Dorsal views, 4 dpf. (B, F) Bright field images at 6 dpf. (C, G) Alcian blue staining of jaw cartilages and (D, H) pectoral fins at 6 dpf. (I) Genetic map of the chromosome 2 region where the two ENU induced lesions are located. The c186 allele is flanked by microsatellite markers z13620 and z60815 (recombination frequencies indicated by numbers in parentheses). Three genes were annotated in this interval: gadd45aa (i); gng12 (ii) and wls/gpr177 (iii). Nonsense mutations in the fh252 (C to T) and c186 (G to A) alleles reside in exons 3 and 7, respectively. (J–M) Rescue of mutant phenotypes by injection of wls mRNA. Lateral views of WT (J), homozygous c186 mutant (K) and rescued c186 mutant (L) TgBAC(gng8:Eco.NfsB-2A-CAAX-GFP) larvae at 7 dpf. The transgene labels habenular neurons and their axons with membrane-tagged GFP. (J′–L′) are dorsal views of the dorsal habenular nuclei. (M) Genotyping of larvae was used to confirm mutant rescue (refer to Section 4 for details).

Recombination mapping of the c186 mutation placed it between z13620 (1 recombinant out of 1238 meioses) and z60815 (13/2066) on chromosome 2 (Fig. 1I), in the vicinity of the zebrafish homolog of the Drosophila wntless (wls) gene (Jin et al., 2010). Positional cloning followed by DNA sequencing verified that the mutation resulted from a single base change (G to A) in the seventh exon of zebrafish wls, leading to a premature stop codon. To verify that the exon 7 lesions was indeed responsible for the mutant phenotype, we generated a second allele, fh252, by Targeted Induction of Local Lesions in Genomes (TILLING; refer to Draper et al., 2004). The fh252 allele is a nonsense mutation in the third exon of the wls homolog, (Fig. 1I). Homozygous fh252 and c186 mutants have identical phenotypes and, as expected, the two mutations fail to complement. The resultant transheterozygous embryos are phenotypically indistinguishable from homozygous mutants for each individual allele, indicating that the two mutations result in an equivalent loss of Wls function (supplementary material Fig. S1). As confirmation that both are null mutations, wls transcripts are not detected by RNA in situ hybridization in either c186 or fh252 homozygous embryos after late epiboly (Fig. 2C, D and data not shown). Absence of wls transcripts allows mutant embryos to be distinguished from their WT siblings at stages prior to when morphological phenotypes are evident.

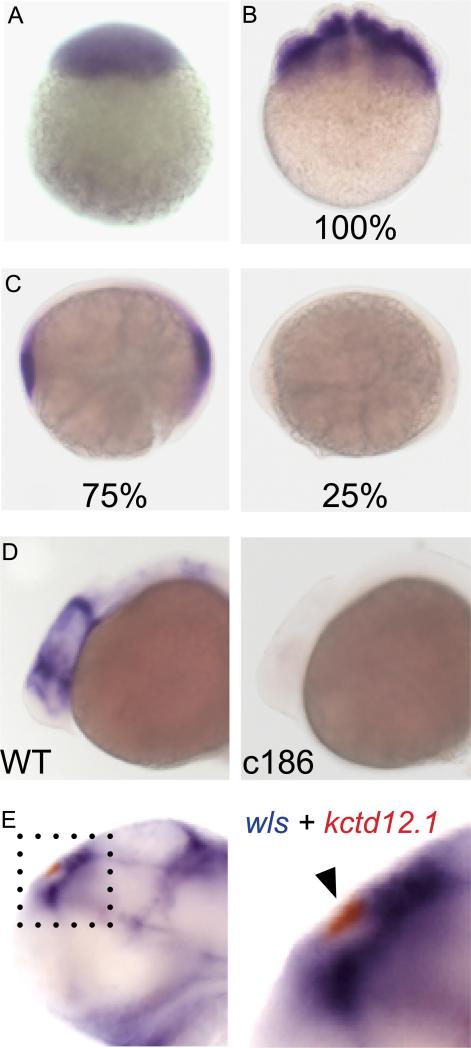

Fig. 2.

wls is maternally deposited and not expressed in the dorsal habenular nuclei. Maternally derived wls transcripts are detected at the (A) 1-cell and (B) 8-cell stage. All embryos derived from heterozygous (wlsc186/+) parents have wls transcripts; however, by (C) 90% epiboly, they are no longer detected in 25% of the progeny. (D) Expression of wls in the diencephalon and midbrain–hindbrain boundary at 24 hpf is not observed in homozygous wls mutants. (E) wls transcripts (blue) are found in cells surrounding but not within the dorsal habenular nuclei (red, indicated by arrowhead in boxed area shown on right). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Injection of in vitro transcribed wls mRNA into 1–2 cell zebra-fish embryos rescues the mutant phenotypes, including formation of appropriately sized dorsal habenular nuclei and habenular innervation of the midbrain target, the interpeduncular nucleus (Fig. 1J–M). The extent of rescue was also assessed by the size and morphology of the pectoral fins, otic vesicles and jaw, and the presence of a swim bladder (Table 1A). To validate rescue of wls homozygous mutants, 25 embryos were scored phenotypically and then processed for DNA extraction and genotyping using a derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence assay (Fig. 1M, refer to Section 4). Several embryos that were scored as indistinguishable from WT or only mildly affected were confirmed to be homozygous mutants (n=8, Table 1B). Although fully rescued mutants developed normal jaws, fins, and swim bladders and lived for several weeks, they did not survive to adulthood, suggesting an essential later role for Wls.

Table 1A.

Frequency of mutant phenotypes reduced following wls RNA injection.

| Swim bladder (%) | Pectoral fins (%) | Otic vesicles (%) | Jaw (%) | Dorsal habenulae (%) | Total embryos | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injected | 19 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 475 |

| Uninjected | 39 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 494 |

Seven independent groups of embryos from matings between wlsc186/+ parents were injected with full-length wls mRNA. At 6 dpf, control and injected embryos were assessed for defects in structures associated with the wls mutant phenotype (i.e., absence of swim bladder, small pectoral fins and otic vesicles, truncated jaw cartilages and reduced dorsal habenular nuclei).

Table 1B.

Phenotypic rescue of homozygous wls mutants.

| Extent of rescue | Swim bladder | Pectoral fin | Otic vesicles | Jaw | Dorsal habenulae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | 62.5% | 62.5% | 25% | 37.5% | 62.5% |

| Partial | n/a | 37.5% | 50% | 62.5% | 37.5% |

| No | 37.5% | 0% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

Embryos obtained from wlsc186/+ parents were injected with wls RNA. The severity of phenotypes was scored at 7 dpf in the indicated structures. Full rescue is defined as indistinguishable from WT, no rescue represents a morphological defect similar to that observed in wls mutants and partial rescue refers to an intermediate phenotype. Larvae were genotyped after phenotypic scoring, and data for 8 confirmed homozygous mutants is shown. Two of the homozygous mutants were completely indistinguishable from WT siblings at the comparable stage.

Bioinformatic analyses support the presence of a single wls gene in the zebrafish genome as in invertebrates and mammals. Regions flanking the zebrafish wls gene on chromosome 2 are syntenic with other teleost species (e.g., medaka and tetraodon, supplementary material Fig. S2). Zebrafish chromosome 6 also shows partial synteny indicative of genomic duplication. However, sequence homology to wls is not detected within the duplicated region where the gene is expected to reside (Supplementary material Fig. S2).

2.2. Maternal and zygotic wls activity

Wnt signaling is necessary for patterning of the germ layers, axis formation and coordinated cell migration during gastrulation (e.g., Harland and Gerhard, 1997; Heisenberg et al., 2000; Kilian et al., 2003; Schier and Talbot, 2005). These processes appear normal in zebrafish wls mutants, suggesting that maternally deposited wls mRNA or protein fulfills the early requirement for Wnt signaling in the developing embryo. Accordingly, maternal wls transcripts are present in 100% of the progeny from heterozygous matings (Fig. 2A, B) until approximately 90% epiboly, at which time transcripts are no longer detected in 25% of the embryos (Fig. 2C–D′).

The analysis of zygotic wls expression is consistent with the previous findings of Jin et al. (2010), who reported transcripts in the diencephalon, jaw, otic vesicles and fins, the same tissues affected in wls mutants (Fig. 2D–E and data not shown). At 48 hpf, wls is strongly expressed in the diencephalon, but not within the developing habenulae themselves (arrowhead, Fig. 2E′).

2.3. Wnt signaling is reduced in zygotic wls mutants

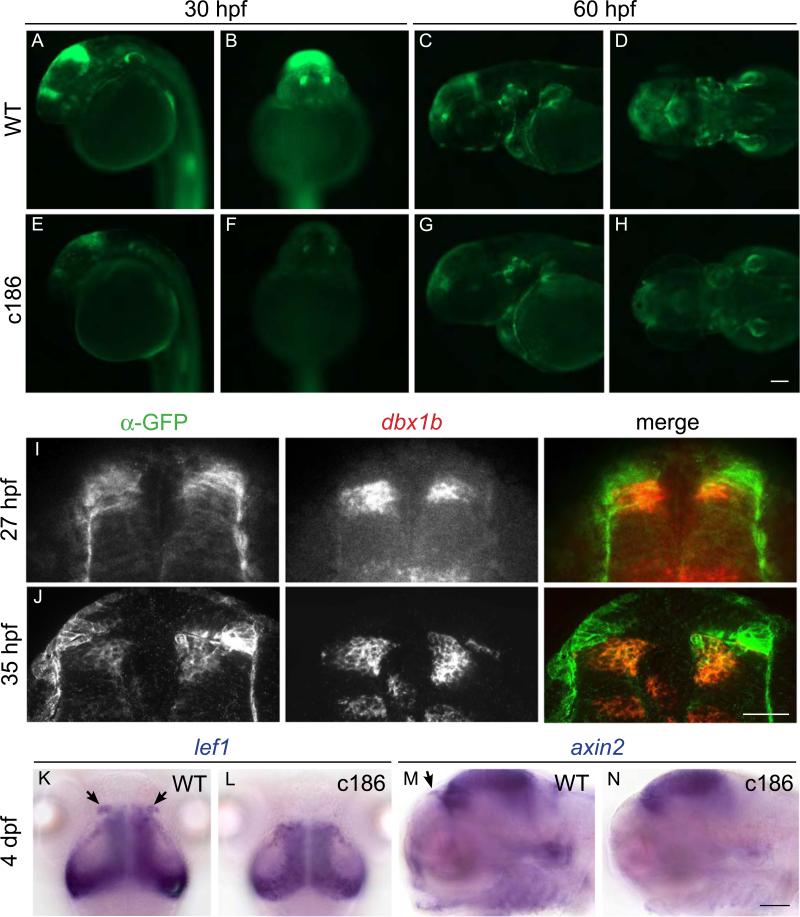

Canonical Wnt signaling is known to play an important role in anterior–posterior patterning of the zebrafish brain (Heisenberg et al., 2001; Paridaen et al., 2009). In the mouse, a conditional wls mutation produced by a Wnt1-Cre driver causes a decrease in canonical Wnt signaling and a loss of the tectum, cerebellum, tegmentum and choroid plexus (Carpenter et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2011). To determine whether zebrafish mutants also show reduced activation of the Wnt pathway, we introduced the wls mutation into Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4, a transgenic line carrying a reporter of canonical Wnt signaling (Moro et al., 2012). As early as 30 hpf, homozygous mutant embryos bearing the transgenic Wnt reporter exhibit a notable decrease in GFP labeling in the dorsal diencephalon, midbrain–hindbrain boundary and otic vesicles (compare Fig. 3A, B to E, F). By 60 hpf, fluorescence is also diminished in the pectoral fins and jaw (Fig. 3C, D and G, H).

Fig. 3.

Wnt signaling is reduced in wls mutants. (A–H) The c186 mutation was introduced into a transgenic reporter of canonical Wnt signaling, Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4 (Moro et al., 2012). At 30 hpf, (A,B) WT siblings show robust GFP labeling in the dorsal diencephalon, midbrain–hindbrain boundary and otic vesicles compared to (E,F) c186 mutants (A, E lateral views, B, F frontal views). By 60 hpf, GFP labeling is also found in the pectoral fins and jaw of (C, D) WT embryos and is reduced in (G,H) c186 mutants (C, G lateral views, D, H dorsal views). (I,J) GFP labeling from Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4 colocalizes with dbx1b expression in the presumptive habenulae at 27 hpf (single section) and 35 hpf (maximum projection of 15 sections at 0.3 μm) (K,M) WT and (L,N) c186 mutant embryos were assayed for expression of the Wnt-responsive genes (K,L) lef1 and (M,N) axin2. Bilateral lef1 expression domains in the dorsal diencephalon (arrows in K) are absent in wls mutants at 4 dpf, as are axin2 transcripts in a similar region of the brain (arrow in M). Expression of axin2 is also reduced in the developing jaw and otic vesicles of (N) wls mutants. (K,L dorsal, M,N lateral views). Scale bar=100 μm for A–H and K–N and 50 μm for I,J.

To determine the relationship between Wnt responsive cells and habenular development, we examined expression of the developing brain homeobox 1b (dbx1b) gene, whose transcripts are highly enriched in the developing habenulae and thalamic progenitors of the mouse (Chatterjee et al., 2014; Quina et al., 2009; Vue et al., 2007) and in proliferating cells of the presumptive dorsal habenulae of zebrafish (Dean et al., 2014). In WT embryos, GFP labeling from the Wnt reporter partially overlaps with dbx1b expression at 27 and 35 hpf (Fig. 3I,J and Supplementary material Movie S1), which confirms that canonical Wnt signaling is occurring within the developing dorsal habenulae.

We next examined whether reduced Wnt activity in the brain affected downstream components of the canonical pathway. Expression of the lef1 and axin2 genes is known to be activated by Wnt signaling (Holland et al., 2013; Jho et al., 2002). Transcripts for lef1 were found at near normal levels in the midbrain, but were noticeably reduced in the dorsal diencephalon at 48 hpf and 4 dpf (Fig. 3K, L and data not shown). Similarly, fewer axin2 transcripts were detected in the dorsal diencephalon, otic vesicles and developing jaw (Fig. 3M, N), regions that are affected in wls mutants. The reduction rather than complete loss of Wnt reporter activity, and the presence of Wnt-dependent gene expression outside of the dorsal diencephalon, indicate that Wnt signaling is only partially diminished in the developing nervous system of zygotic wls mutants.

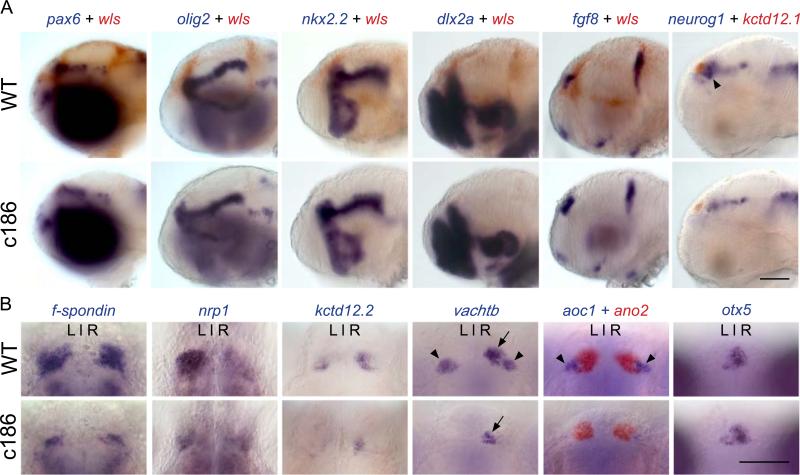

2.4. Patterning of the brain and habenular L–R asymmetry are intact in wls mutants

Despite the reduction in labeling from the canonical Wnt reporter, the morphology and regionalization of the brain is largely normal in wls mutant embryos. Anterior–posterior and dorsal–ventral patterns of gene expression are indistinguishable from WT embryos (Fig. 4A). An exception is expression of neurogenin-1 (neurog1) in a small domain in the dorsal diencephalon just ventral and caudal to the habenulae. This domain is significantly reduced or absent in wls mutants compared to their WT siblings (arrowheads, Fig. 4A). We assessed whether the lack of neurog1 expression is responsible for the small dorsal habenulae by examining neurog1hi1059 homozygous mutants (Golling et al., 2002). The size of the dorsal habenular nuclei is similar in mutant and WT brains (Supplementary material Fig. S3), indicating that while loss of Wls leads to a decrease in neurog1-expressing cells in the diencephalon, a reduction in neurog1 itself does not appear to affect dorsal habenular development.

Fig. 4.

Defects in brain patterning confined to dorsal diencephalon. (A) Spatially restricted patterns of gene expression in the brains of WT and wls mutant larvae at 48 hpf. WT larvae are distinguished from homozygous wls mutants by the presence of wls transcripts (red), with the exception of kctd12.1 (red) and neurog1 double-labeling, where they are distinguished by dorsal habenular size. The neurog1 expression domain adjacent to the habenulae (arrowhead in WT) is reduced in wls mutants. (B) Gene expression in the habenular region. The dorsal habenulae of wls mutants show reduced f-spondin and ano2 expression but, despite their smaller size, L–R asymmetric gene expression (nrp1, kctd12.2, vachtb) is maintained (right dorsal nucleus indicated by arrow for vachtb). Expression of vachtb and aoc1 in the ventral habenulae (arrowheads in WT) is largely absent in wls mutants. The parapineal is positioned to the left of the pineal analage, as determined by otx5 expression, in WT and wls mutant siblings. Scale bars=100 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As Wnt signaling has been shown to influence L–R asymmetry of the dorsal habenulae (Carl et al., 2007; Hüsken et al., 2014) and is important for formation of the ventral habenular nuclei (Beretta et al., 2013), we examined whether these features are disrupted in the absence of Wls. The bilateral expression domains of genes such as f-spondin and ano2 are smaller in wls mutants compared to WT siblings (Fig. 4B). Although the dorsal habenulae are reduced in size, and consistent with the initial results on kctd 12.1 (Fig.1A, E), the asymmetric expression patterns of genes showing either a left- or right-sided bias are preserved (Fig. 4B). Leftward migration of the parapineal, a structure known to influence habenular laterality (Gamse et al., 2003, Concha et al., 2000), also appears unperturbed in wls mutants, as determined by expression of otx5 in the pineal and parapineal (Fig. 4B). However, as in tcf7l2 mutants (Beretta et al., 2013), the ventral habenular nuclei of wls mutants are absent (Fig. 4B). These findings indicate that the functions of Wnt signaling in L–R asymmetry of the epithalamus and formation of the ventral habenular nuclei are separable.

2.5. Habenular precursor populations are affected in wls mutants

The small size of the dorsal habenulae of wls mutants could result from abnormal neurogenesis, as it is well known that Wnt signaling influences this process (Ciani and Salinas, 2005; Ille and Sommer, 2005). To assess cell death and cell proliferation we performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) to detect apoptotic cells and immunolabeing using a phospho-Histone H3 (pH3) antibody that recognizes mitotic cells, at stages when the developing habenulae could be distinguished in TgBAC(dbx1b:GFP) embryos. An equivalent low number of TUNEL positive cells (0–2 cells, data not shown) were detected at 27 hpf in the GFP labeled habenular region of c186 homozygotes (n=6) as in their WT siblings (n=12). At 48 hpf, actively dividing pH3+ cells were found in equivalent numbers relative to the volume of the dbx1b:GFP habenular domain in mutant and WT embryos (Supplementary material Fig. S4). Therefore, neither increased cell death, nor disruption of proliferation appears responsible for the reduced dorsal habenulae of wls mutants.

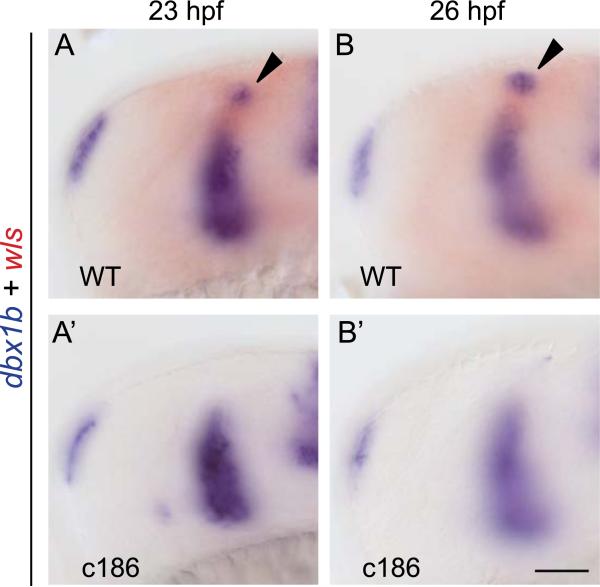

An alternative role for Wls-dependent Wnt signaling could be in the specification and/or maintenance of habenular progenitors. To test for this, we examined dbx1b expression at 23 hpf, when transcripts are first detected in the dorsal diencephalon of the majority (57%) of WT embryos. At this stage, dbx1b transcripts were not detected in the same brain region of wls mutants (Fig. 5 A–A′; Table 2). By 26 hpf, when almost all WT siblings show robust dbx1b expression in the developing habenulae (92%; Table 2), only a few dbx1b+ cells were observed in 27% of wls mutants (Fig. 5B–B′; Table 2). These findings suggest that there is a temporal delay in the development of the dbx1b+ habenular progenitor cell population.

Fig. 5.

dbx1b+ expression in the developing habenulae is delayed in wls mutants. Lateral view of dbx1b transcripts in the dorsal diencephalon of (A–A′) 23 hpf and (B–B′) 26 hpf WT and c186 embryos. At these early stages, wls expression (red) distinguishes WT siblings from homozygous mutants. Scale bar=50 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Expression of dbx1b is delayed in the developing habenulae of wls mutants.

| Presence of dbx1b+ cells (hpf) | WT (%) | wls mutants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 23 | 57 (n = 19) | 0 (n = 5) |

| 26 | 92 (n = 13) | 27 (n = 11) |

Percent of embryos with dbx1b expression in the habenular region at 23 and 26 hpf for wlsc186 mutants and their WT siblings.

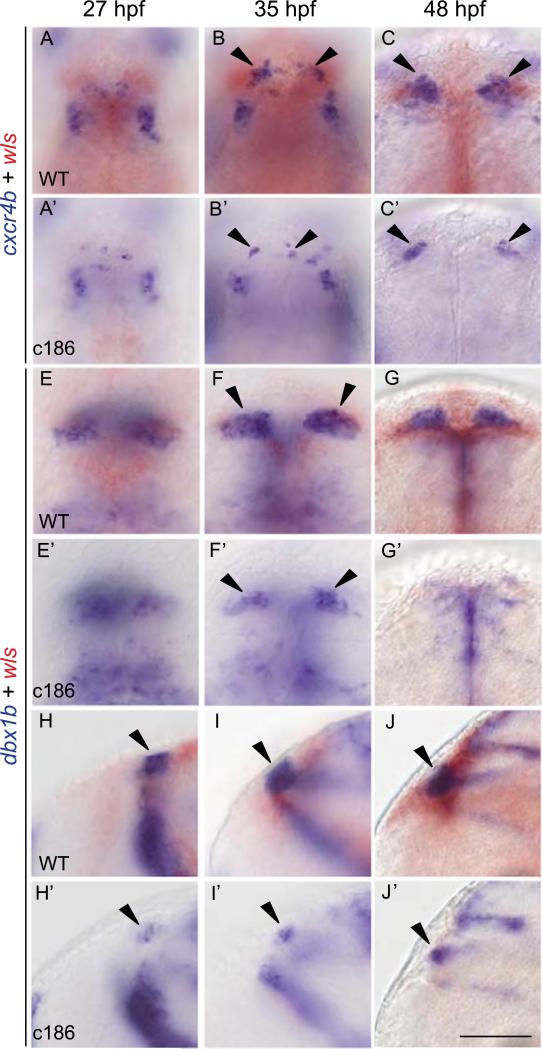

Previously, the chemokine (C–X–C motif) receptor 4b (cxcr4b) gene was described as another marker of habenular progenitor cells or early habenular neurons (Roussigné et al., 2009). Since cxcr4b is expressed in a similar pattern as neurog-1 (Roussigné et al., 2009), a global marker of neural progenitors whose expression is reduced in wls mutants (Fig. 4A), we hypothesized that the small dorsal habenulae could also result from a lack of cxcr4b+ cells. From 27 hpf onward, homozygous wls mutants show characteristic defects in both the dbx1b and cxcr4b-expressing habenular populations, while expression of these genes is unperturbed in other regions of the brain (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Compared to WT, fewer cxcr4b+ cells were found in the diencephalon of wls mutants at 27 hpf and 35 hpf (arrowheads Fig. 6A–B′). As early as 27 hpf, the bilateral dbx1b+ habenular domains are noticeably smaller (Fig. 6E–F′,H–I′) and, by 48 hpf, the presumptive habenulae of wls mutants, as defined by cxcr4b (Fig. 6C,C′) and dbx1b (Fig. 6G,G′,J,J′) expression, are significantly reduced in size. Thus, a deficit in two progenitor populations accounts for the small dorsal habenular nuclei of wls mutant zebrafish.

Fig. 6.

Habenular precursor populations are reduced in wls mutants. (A–C′) Dorsal views of cxcr4b expression in the diencephalon of WT and wls homozygous mutant embryos. Dorsal (E–G′) and lateral (H–J′) views of dbx1b expression in WT and wls mutant embryos. wls transcripts (red) were used to distinguish WT siblings from homozygous mutants. Scale bar=100 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3. Discussion

During the course of a mutagenesis screen to identify genes that regulate habenular development, we isolated a mutation that results in small dorsal habenular nuclei and localized it to the zebrafish homolog of the wntless gene. The Wntless protein is essential for the transport of Wnts to the cell surface in both invertebrates and mammals (Das et al., 2012). Our study now implicates Wls in proper formation of the habenular region of the zebrafish forebrain. Zebrafish wls is expressed in the developing dorsal diencephalon in domains directly adjacent to but not within the habenulae. Characterization of the wls mutant phenotype supports distinct requirements for Wnt signaling in habenular development: an early function in establishing L–R asymmetry of the dorsal nuclei (Carl et al., 2007; Hüsken et al., 2014) and later roles in formation of the ventral habenular nuclei (Beretta et al., 2013) and in the generation of a complete repertoire of dorsal habenular progenitors.

3.1. Identification of a zebrafish wntless homolog

A wls homolog was previously isolated from the zebrafish genome on the basis of the high amino acid identity of its predicted protein with the human and mouse Wntless proteins (Jin et al., 2010). The zebrafish protein is 78% identical to human WLS isoform 1 and 76% to mouse isoform a, but only 42% identical to the Wls isoform B of Drosophila. In addition to sequence conservation at the amino acid level, we determined that the predicted zebrafish protein contains a tyrosine–glutamate–glycine–leucine (YEGL) motif that is required for retromer-dependent recycling from the cell membrane (Gasnereau et al., 2011). Analyses of sequence homology and syntenic chromosomal regions indicate that this is the sole Wls gene in the zebrafish genome.

The initial ENU induced c186 mutation and the fh252 mutation identified by TILLING contain premature stop codons in exons 7 and 3, respectively. Both are loss-of-function mutations since aberrant, zygotically-derived wls mRNA is not detected in homozygous mutants and is most likely a target of nonsense-mediated decay.

3.2. Conserved aspects of the zebrafish wls mutant phenotype

Zebrafish wls mutants show defects in a variety of tissues, including the jaw and pectoral fin cartilages and the otic vesicles. Previous studies using a morpholino to deplete zebrafish Wls also reported irregularities in jaw and otic vesicle development (Jin et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2015). In addition, severe phenotypes such as small heads and cardiac edema were described (Jin et al., 2010) that are not observed in wls homozygous mutants, indicative of non-specific morpholino toxicity. Conditional mouse mutants generated with a Wnt1:Cre driver show craniofacial abnormalities reminiscent of the jaw phenotype of wls mutant zebrafish (Carpenter et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2011). A reduction in limb structures, analogous to the fish pectoral fin, was observed in conditional wls mutant mice produced with a Prx1:Cre driver (Zhu et al., 2012). Defects in the ear and habenular region of the brain have not yet been reported in conditional wls mutant mice; however, the development of these tissues may depend on Wls derived from other sources than wnt1- or prx1-expressing cells. Thus, the use of additional Cre driver lines may reveal alterations in analagous structures in zebrafish and mice.

3.3. Does Wntless mediate all Wnt signaling in zebrafish?

Given the role of Wls in Wnt signaling, we expected to find numerous Wnt-related defects in zebrafish homozygous mutants. However, zebrafish wls mutants undergo surprisingly normal early development. This contrasts with wnt5b and wnt11 mutants, which have severe abnormalities in convergence-extension during axis formation (Heisenberg et al., 2000, Marlow et al., 2004) or other Wnt signaling mutants that show disruptions in brain patterning and organogenesis (e.g., Heisenberg et al., 2001; Hikasa and Sokol, 2013; Lee et al., 2006, Lin and Xu, 2009, Matsui et al., 2005, Paridaen et al., 2009; Poulain and Ober, 2011). Furthermore, expression of genes downstream of canonical Wnt signaling is only notably affected in the dorsal diencephalon of wls mutants and labeling from a transgenic reporter of canonical Wnt signaling is also diminished rather than absent and low levels of GFP labeling persist in mutants as late as 6 dpf.

A likely explanation for the relatively normal early development of wls mutants and the persistence of Wnt reporter activity is the presence of maternally deposited mRNA and protein. Given that maternally deposited WT wls mRNA can persist until 90% epiboly (8–9 hpf), Wls protein could be present throughout much of early embryonic development in zygotic mutants. Indeed, a recent study confirms the presence of maternally derived Wls protein in zebrafish embryos, at levels sufficient for embryos injected with wls antisense morpholinos to develop normally at early stages (Wu et al., 2015). Maternal deposition could also account for the difference in phenotypic severity between zebrafish wls homozygotes and wls mutant mice (Carpenter et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2009) or Drosophila embryos derived from wls mutant germline clones (Banziger et al., 2006; Bartscherer et al., 2006; Goodman et al., 2006). The precise roles of maternally provided Wls need to be rigorously tested in zebrafish by eliminating the maternal contribution and generating a maternal-zygotic mutant.

An alternative possibility to account for the relatively mild phenotype of wls homozygotes is that some Wnts may be released in a Wls-independent manner. A subset of genes that are positively regulated by and highly sensitive to Wnt signaling are transcribed at low levels in Drosophila lacking wls function (Banziger et al., 2006; Goodman et al., 2006), suggesting that in the absence of Wls, some Wnt signals can still be received by Wnt-responsive cells. Wnt family members have also been identified that do not require the acyltransferase Porcupine, which, unless they are lipid modified by a different mechanism, would allow for their secretion independent of Wls (Chen et al., 2012; Richards et al., 2014). WntD, for example, is neither lipidated nor requires Wls for its intracellular trafficking and secretion from Drosophila cells (Ching et al., 2008). Depletion of zebrafish Wls using an antisense morpholino further argues for a differential requirement for this protein in Wnt trafficking, as membrane localization of fluorescently tagged Wnt5b is severely disrupted, whereas Wnt11 persists at the cell membrane, indicative of active secretion (Wu et al., 2015). Moreover, not all wnt genes show co-expression with wls in the zebrafish embryo (Kuan and Halpern, unpublished), suggesting that alternative strategies must exist for trafficking of the Wnts that they encode. A recent study suggests that a protein homologous to Caenorhabditis elegans Unc119-c may perform similar functions to Wls as a Wnt chaperone in zebrafish (Toyama et al., 2013).

3.4. Multiple roles for Wnt signaling in habenular development

Several features of habenular development have been attributed to the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Analyses of axin1 and tcf7l2 mutants indicate that Wnt signaling is important for directional asymmetry of the dorsal habenulae (Carl et al., 2007; Hüsken et al. 2014). It is therefore surprising that L–R differences between the dorsal habenulae are intact in wls mutants.

Another demonstrated function of the Wnt signaling pathway is in the formation of the ventral habenulae, which are lacking in tcf7l2 mutants (Beretta et al., 2013). Markers of the ventral habenulae are also undetected or their expression greatly diminished in wls mutants. Thus, while L–R asymmetry of the dorsal nuclei and formation of the ventral nuclei are both reliant on Wnt signaling (Beretta et al., 2013; Hüsken et al., 2014), analysis of the wls mutant phenotype demonstrates that these features of habenular development are independently regulated. The most parsimonious explanation is that there are temporally distinct roles for canonical Wnt signaling, with an early function in L–R asymmetry and a later one in the formation of the ventral habenulae. L–R differences in the developing brain are found as early as 18 hpf, as evidenced by expression of lefty1, cyclops, and pitx2 on the left side of the dorsal diencephalon (Concha et al., 2000; Rebagliati et al., 1998; Sampath et al., 1998; Thisse and Thisse, 1999). In contrast, ventral habenular precursors are thought to be present at 2 dpf (Beretta et al., 2013). Because of this difference in timing, we propose that maternally derived Wls activity plays a role in the establishment of directional asymmetry and determination of dorsal habenular L–R identity, whereas zygotic Wls is necessary for specification of the ventral nuclei.

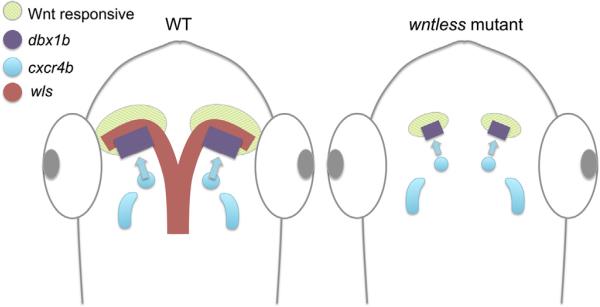

Characterization of the wls phenotype reveals an additional role for Wnt signaling in the regulation of dorsal habenular precursor populations, as depicted schematically in Fig. 7. As early as 27 hpf, Wnt responsive cells are found within the dbx1b domain, suggesting that proper development of dorsal habenular progenitors is dependent on Wnt signaling. Attenuated Wnt signaling in the diencephalon may cause the delay in the production of and ultimate reduction in numbers of dbx1b+ dorsal habenular progenitors. By 35 hpf, there are notably fewer cxcr4b-expressing cells in the developing habenulae, though they are present more caudally in the diencephalon. Given the known role of Cxcr4b in cell migration of the lateral line primordium and olfactory placodes (Miyasaka et al., 2007; Venkiteswaran et al., 2013), we suspect that the cxcr4b-expressing habenula progenitors migrate anteriorly to join the newly forming dbx1b-expressing dorsal habenulae. Recruitment of fewer cxcr4b-expressing cells to the dbx1b-expressing presumptive habenulae could further reduce the mutant dorsal habenular nuclei. Intriguingly, mutations in axin1 or tcf7l2 do not cause a reduction in the size of the dorsal habenulae (Carl et al., 2007; Hüsken et al., 2014) as observed in wls mutants. Proper formation of the dbx1b presumptive dorsal habenulae and recruitment of the cxcr4b-expressing habenular progenitors may, therefore, rely on other downstream components in the Wnt signaling pathway.

Fig. 7.

Role of Wntless in dorsal habenular development. Schematic model whereby Wls-dependent canonical Wnt signaling influences formation of the dbx1b-expressing presumptive dorsal habenulae and the subsequent recruitment of cxcr4b-expressing progenitors. Diminished Wnt signaling in homozygous wls mutants is proposed to reduce the dbx1b-expressing habenular domain and migration of the cxcr4b+ population to the dorsal habenulae.

Reduced habenular size has been implicated in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (Ranft et al., 2010; Savitz et al., 2011). Intriguingly, lithium chloride, a common treatment for bipolar disorder, is both a Wnt agonist (Klein and Melton, 1996) and increases habenular volume in bipolar patients (Savitz et al., 2011). While it is premature to propose a causal relationship between habenular size and psychiatric disorders, wls mutants provide a valuable model to explore the multiple roles of Wnt signaling in the development and ultimately the function of the habenular region of the brain.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Zebrafish strains and husbandry

Zebrafish were maintained at 28 °C on a 14:10 light: dark cycle. The wildtype AB strain (Walker, 1999), the N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) induced mutations wlsc186 and wlsfh252 and the transgenic lines Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4 (Moro et al., 2012), TgBAC(dbx1b:GFP) (Kinkhabwala et al., 2011) and TgBAC(gng8:Eco.NfsB-2A-CAAX-GFP) (deCarvalho et al. 2013) were used. Maintenance and care of zebrafish and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Carnegie Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

4.2. ENU mutagenesis and gene identification

Mutations were induced by exposure of AB males to ENU as previously described (Haffter et al., 1996). Mutant phenotypes were identified in the F3 generation following screening for expression of kctd12.1. Carriers were outcrossed to AB fish to maintain and expand the line. To generate a mapping panel, c186 heterozygous males were mated to WIK (Rauch et al., 1997) females. The position of the c186 lesion was determined by bulked segregation analysis using simple sequence repeat length polymorphisms (SSLP) (Talbot and Schier, 1999). Sequences for SSLP primers are provided at http://www.zfin.org, with the exception of the ys-Lg2-12 primers (5′-TCC AGC AGT CAA ATC AGG TG -3′ and 5′-TCC AGC AGT CAA ATC AGG TG-3′), which were designed based on genomic DNA sequence. Exons of the zgc:64091 transcript (NCBI accession# NM_213146.1) were PCR amplified for DNA sequencing using the following primers:

exon 1: 5′-GAGCCTGGCCGTGTGACGTCA-3′ and 5′-ACCAAACTGGAAACACACTGTGCA-3′

exon 2: 5′-GAATCGAAAATGTAATCGAATAGAGG-3′ and 5′-AATCGCCAATATGGATGAGGAG-3′

exons 3 and 4: 5′-CAGTGCAGCAACGTTTACTGTTT-3′ and 5′-TGTGCGTTTTAGACATGCATCC-3′

exon 5: 5′-AGCAAACAACGATACCCATCAA-3′ and 5′-AGAACACCCAGACAACCACAA- 3′

exon 6: 5′-TGTTTCTTGGTGAGGTGTGCT-3′ and 5′-ATTCTGCACCAATTGATCCAC-3′

exons 7 and 8: 5′-AAAAAAGTGGGTCCAACCTGGTAC-3′ and 5′-ACAGCACAGCAACCATCACAAT-3

exon 9: 5′-GACCATACTATTGTGATGGTTG-3′ and 5′-TGCCTTCTGCATCACTTTTGAC-3′.

exon 10 and 11: 5′-GTTTGCTCGTTACTGAACCCAT-3′ and 5′-CACACTATTTACTTATGCACTTAC CCA-3′.

The fh252 allele was generated by TILLING as described previously (Draper et al., 2004).

4.3. Genotyping

Genotyping of the c186 allele was performed using a derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (dCAPS). Genomic DNA was PCR amplified using forward (5′-GACTGAGAGGAACCGCTTTTCAGTGTTCT-3′) and reverse (5′-AGAAAGGATTCT TTAGCTGTACTCCTCTGC-3′) primers. The forward primer contains a mismatch, generating a DNA fragment that is sensitive to XbaI digestion in the c186 allele but not in WT.

4.4. RNA injection

The zgc:64091 clone corresponding to full-length wls cDNA was purchased from the ATTC Resource Center, Manassas, VA. Sense RNA was produced using the mMESSAGE mMachine Kit (Ambion). For mutant rescue, approximately 1 nL of RNA (0.3 ng/nL in 0.2% phenol red and sterile water) was injected into zebrafish embryos at the 1–2 cell stage.

4.5. Bioinformatic analyses

Low homology screens to identify additional wls genes in the zebrafish genome were performed using BLAST and tBLASTx algorithms (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Syntenic regions were found by examining the genes flanking wls and searching for duplicated copies of their coding sequences in the zebrafish genome or for homologous genes in the genomes of other teleost species (www.ensembl.org).

4.6. RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence

Techniques for colormetric and fluorescent in situ hybridizations were performed as described previously (deCarvalho et al., 2013). RNA probes for pax6 (Krauss et al., 1991), dlx2a (Akimenko et al., 1994), fgf8 (Fürthauer et al., 1997), wls, neurog1, cxcr4b (Thisse et al., 2001), olig2 (Park et al., 2002), nkx2.2 (Thisse and Thisse, 2004), dbx1b (Gribble et al., 2007), kctd12.1, kctd12.2, f-spondin, (Gamse et al., 2003; Gamse et al., 2005), nrp1a (Yu et al., 2004), vachtb (Hong et al., 2013) and ano2 (deCarvalho et al., 2014) were synthesized according to the published methods. cDNA fragments for lef1 and axin2 were generated by RT-PCR using primers 5′-TGGCATGCTTTATCTCGGGAA-3′ and 5′- GTCAAAGATGCCTATTTATTTCCA-3′ and 5′-AAGTCGCACAGTTTGGAACC-3′ and 5′-CACATCATCGGCTATTGGCT-3′, respectively. The amplified fragments were cloned into pCRII by TOPO TA-cloning (Invitrogen K4600-01).

Immunolabeling to detect GFP or pH3 was performed as described previously (deCarvalho et al., 2013) using rabbit GFP antisera (Torrey Pines Biolabs) or anti-phospho-Histone H3 (ser10) antibody (Millipore), respectively, and Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). To quantify the number of cells undergoing mitosis in the presumptive dorsal habenulae, ph3 immunolabeling was performed on WT and c186 mutant embryos carrying the TgBAC(dbx1b:GFP) transgene that labels this brain region. From a confocal z-stack, 3D images were processed using Imaris software (Bitplane) and the volume of the dbx1b:GFP habenular domain was calculated using the ‘surfaces’ function. Only pH3+ nuclei found within this domain were counted using the ‘spots’ function, which was set to identify labeled spheres approximately 5 μm in diameter. The number of labeled nuclei was normalized to habenular volume and a two-tailed t-test was used to compare mutant and WT values.

4.7. Alcian Blue staining

Larvae were collected at 6 dpf, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight and stored in PBS at 4 °C. Alcian Blue (0.1% in 0.37% hydrochloric acid (HCl), 70% ethanol) was used to label cartilage according to standard methods (Schilling et al., 1996).

4.8. Microscopy

Bright field images were collected on a Zeiss Axioskop with an AxioCam HRc camera. Images incorporating both bright field and fluorescence were obtained using a Zeiss AxioZoom.V16 fitted with an AxioCam MRm. Confocal images were acquired with upright or inverted Leica SP5 microscopes using 40 × oil immersion and 25 × water immersion lens, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rejji Kuruvilla for valuable feedback and Michelle Macurak for technical assistance. We are grateful to Bruce Appel, Bernard Thisse, Christine Thisse, Randy Moon, Monte Westerfield, Deborah Yelon, Ajay Chitnis and Brian Harfe for generously sharing reagents. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to CM (5R01HD076585-08) and MEH (5R01HD042215-10).

Footnotes

Author contribution

Yung-Shu Kuan and Sara Roberson conceived of and performed experiments, analyzed data and prepared the manuscript. Courtney M. Akitake also provided experimental results and edited the manuscript prior to submission. Lea Fortuno and Joshua Gamse carried out the genetic screen that identified the initial wls mutation and contributed data and reagents. Cecilia Moens provided a second TILLED allele and all authors critiqued the manuscript. Marnie E. Halpern oversaw the project and assisted with experimental design, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.06.006.

References

- Aizawa H, Amo R, Okamoto H. Phylogeny and ontogeny of the habenular structure. Front. Neurosci. 2011;5:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H. Habenula and the asymmetric development of the vertebrate brain. Anat. Sci. Int. 2013;88:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12565-012-0158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimenko MA, Ekker M, Wegner J, Lin W, Westerfield M. Combinatorial expression of three zebrafish genes related to Distal-Less: part of a homeobox gene code for the head. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:3475–3486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03475.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banziger C, Soldini D, Schutt C, Zipperlen P, Hausmann G, Basler K. Wntless, a conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell. 2006;125:509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartscherer K, Pelte N, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M. Secretion of Wnt ligands requires Evi, a conserved transmembrane protein. Cell. 2006;125:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta C, Dross N, Bankhead P, Carl M. The ventral habenulae of zebrafish develop in prosomere 2 dependent on Tcf7l2 function. Neural Dev. 2013;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl M, Bianco I, Bajoghli B, Aghaallaei N, Czerny T, Wilson SW. Wnt/ Axin1/B-Catenin signaling regulates asymmetric Nodal activation, elaboration, and concordance of CNS asymmetries. Neuron. 2007;55:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter AC, Rao S, Wells JM, Campbell K, Lang RA. Generation of mice with a conditional null allele for wntless. Genesis. 2010;48:554–558. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Guo Q, Weber S, Schlopp S, Li J. Pax6 regulates the formation of the habenular nuclei by controlling the temporospatial expression of Shh in the diencephalon in vertebrates. BMC Biol. 2014;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Takada R, Takada S. Loss of Porcupine impairs convergent extension during gastrulation. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:2224–2234. doi: 10.1242/jcs.098368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching W, Hang HC, Nusse R. Lipid-independent secretion of a Drosophila Wnt protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:17092–17098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802059200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani L, Salinas PC. Wnts in the vertebrate nervous system: from patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:351–362. doi: 10.1038/nrn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha ML, Burdine RD, Russell C, Schier AF, Wilson SW. A Nodal signaling pathway regulates the laterality of neuroanatomical asymmetries in the zebrafish forebrain. Neuron. 2000;28:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudreuse D, Korswagen HC. The making of Wnt: new insights into Wnt maturation, sorting and secretion. Development. 2007;134:3–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.02699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Yu S, Sakamori R, Stypulkowski E, Gao N. Wntless in Wnt secretion: molecular, cellular and genetic aspects. Front. Biol. 2012;7:587–593. doi: 10.1007/s11515-012-1200-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean BJ, Erdogan B, Gamse JT, Wu SY. Dbx1b defines the dorsal habenular progenitor domain in the zebrafish epithalamus. Neural Dev. 2014;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCarvalho TN, Akitake CM, Thisse C, Thisse B, Halpern ME. Aversive cues fail to activate fos expression in the asymmetric olfactory habenula pathway in zebrafish. Front. Neural Circ. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCarvalho TN, Subedi A, Rock J, Harfe BD, Thisse C, Thisse B, Halpern ME, Hong E. Neurotransmitter map of the asymmetric dorsal habenular nuclei of zebrafish. Genesis. 2014;52:636–655. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper BW, McCallum CM, Stout JL, Slade AJ, Moens CB. A high-throughput method for identifying N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced point mutations in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;77:91–112. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)77005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franch-Marro X, Wendler F, Guidato S, Griffith J, Baena-Lopez A, Itsaki N, Maurice MM, Vincent JP. Wingless secretion requires endosome-to-Golgi retrieval of Wntless/Evi/Sprinter by the retromer complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:170–177. doi: 10.1038/ncb1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Jiang M, Mirando AJ, Yu HI, Hsu W. Reciprocal regulation of Wnt and Gpr177/mouse Wntless is required for embryonic axis formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:18598–18603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904894106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Yu HMI, Maruyama T, Mirando AJ, Hsu W. Gpr177/mouse Wntless is essential for Wnt-mediated craniofacial and brain development. Dev. Dynam. 2011;240:365–371. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürthauer M, Thisse C, Thisse B. A role for FGF-8 in the dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish gastrula. Development. 1997;124:4253–4264. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamse JT, Thisse C, Thisse B, Halpern ME. The parapineal mediates left-right asymmetry in the zebrafish diencephalon. Development. 2003;130:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamse JT, Kuan YS, Macurak M, Brösamle C, Thisse B, Thisse C, Halpern ME. Directional asymmetry of the zebrafish epithalamus guides dorsoventral innervation of the midbrain target. Development. 2005;132:4869–4881. doi: 10.1242/dev.02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasnereau I, Herr P, Chia PZC, Basler K, Gleeson PA. Identification of an endocytosis motif in an intracellular loop of Wntless, essential for its recycling and the control of Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:43324–43333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golling G, Amsterdam A, Sun Z, Antonelli M, Maldonado E, Chen W, Burgess S, Haldi M, Artzt K, Farrington S, et al. Insertional mutagenesis in zebrafish rapidly identifies genes essential for early vertebrate development. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:135–140. doi: 10.1038/ng896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RM, Thombre S, Firtina Z, Gray D, Betts D, Roebuck J, Spana EP, Selva EM. Sprinter: a novel transmembrane protein required for Wg secretion and signaling. Development. 2006;133:4901–4911. doi: 10.1242/dev.02674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble SL, Nikolaus OB, Dorsky RI. Regulation and function of dbx genes in the zebrafish spinal cord. Dev. Dynam. 2007;236:3472–3483. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Kane DA, Odenthal J, van Eeden FJ, Jiang YJ, Heisenberg CP, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R, Gerhard J. Formation and function of Spemann's organizer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:611–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg CP, Tada M, Rauch GJ, Saude L, Concha ML, Geisler R, Stemple DL, Smith JC, Wilson SW. Silberblick/Wnt11 mediates convergent extension movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature. 2000;405:76–81. doi: 10.1038/35011068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg CP, Houart C, Take-uchi M, Rauch GJ, Young N, Coutinho P, Masai I, Caneparo L, Concha ML, Geisler R, et al. A mutation in the Gsk3-binding domain of the zebrafish Masterblind/Axin1 leads to a fate transformation of telencephalon and eyes to diencephalon. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1427–1434. doi: 10.1101/gad.194301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Wnt signaling in vertebrate axis specification. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a007955. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:203–213. doi: 10.1038/nrn2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JD, Klaus A, Garratt AN, Birchmeier W. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013;25:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E, Santhakumar K, Akitake CM, Ahn SJ, Thisse C, Thisse B, Wyart C, Mangin JM, Halpern ME. Cholinergic left–right asymmetry in the habenulo-interpeduncular pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:21171–21176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319566110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüsken U, Stickney HL, Gestri G, Bianco IH, Faro A, Young RM, Roussigne M, Hawkins TA, Beretta CA, Brinkmann I, et al. Tcf7l2 Is required for left–right asymmetric differentiation of habenular neurons. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ille F, Sommer L. Wnt signaling: multiple functions in neural development. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1100–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho E, Zhang T, Domon C, Joo C, Freund J, Costantini F. Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–1183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Morse M, Frey C, Petko J, Levelnson R. Expression of GPR177 (Wntless/Evi/Sprinter), a highly conserved Wnt-transport protein, in rat tissues, zebrafish embryos, and cultured human cells. Dev. Dynam. 2010;239:2426–2434. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke J, Xu H, Williams BO. Lipid modification in Wnt structure and function. Curr. Opini. Lipidol. 2013;24:129–133. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32835df2bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian B, Mansukoski H, Barbosa FC, Ulrich F, Tada M, Heisenberg CP. The role of Ppt/Wnt5 in regulating cell shape and movement during zebrafish gastrulation. Mech. Dev. 2003;120:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkhabwala A, Riley M, Koyama M, Monen J, Satou C, Kimura Y, Higashijima SI, Fetcho J. A structural and functional ground plan for neurons in the hindbrain of zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:1164–1169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012185108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss S, Johansen T, Korzh V, Moens U, Ericson JU, Fjose A. Zebrafish pax[zf-a]: a paired box-containing gene expressed in the neural tube. EMBO J. 1991;10:3609–3619. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Wu S, Goering LM, Dorsky RI. Canonical Wnt signaling through Lef1 is required for hypothalamic neurogenesis. Development. 2006;133:4451–4461. doi: 10.1242/dev.02613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Xu X. Distinct functions of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in KV development and cardiac asymmetry. Development. 2009;136:207–217. doi: 10.1242/dev.029561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow F, Gonzales EM, Yin C, Rojo C, Solnica-Krezel L. No tail cooperates with non-canonical Wnt signaling to regulate posterior body morphogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2004;131:203–216. doi: 10.1242/dev.00915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Callol-Massot C, Capdevila J, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Belmonte JCI. Noncanonical Wnt signaling regulates mid-line convergence of organ primordia during zebrafish development. Genes Dev. 2005;19:164–175. doi: 10.1101/gad.1253605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka N, Knaut H, Yoshihara Y. Cxcl2/Cxcr4 chemokine signaling is required for placode assembly and sensory axon pathfinding in the zebrafish olfactory system. Development. 2007;134:2459–2468. doi: 10.1242/dev.001958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro E, Ozhan-Kizil G, Mongera A, Beis D, Wierzbicki C, Young RM, Bournele D, Domenichini A, Valdivia LE, Lum L, et al. In vivo Wnt signaling tracing through a transgenic biosensor fish reveals novel activity domains. Dev. Biol. 2012;366:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdi R, Proffitt K, Sprowl S, Kaur S, Yu J, Covey T, Virshup D, Waterman M. A uniform human Wnt expression library reveals a shared secretory pathway and unique signaling activities. Differentiation. 2012;84:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paridaen JTML, Danesin C, Elas AT, van de Water S, Houart C, Zivkovic D. Apc1 is required for maintenance of local brain organizers and dorsal midbrain survival. Dev. Biol. 2009;331:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Mehta A, Richardson JS, Appel B. olig2 is required for zebrafish primary motor neuron and oligodendrocyte development. Dev. Biol. 2002;248:356–368. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port F, Basler K. Wnt trafficking: new insights into Wnt maturation, secretion and spreading. Traffic. 2010;11:1265–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain M, Ober EA. Interplay between Wnt2 and Wnt2bb controls multiple steps of early foregut-derived organ development. Development. 2011;138:3557–3568. doi: 10.1242/dev.055921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quina L, Wang S, Ng L, Turner E. Brn3a and Nurr1 mediate a gene regulatory pathway for habenula development. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14309–14322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2430-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranft K, Dobrowolny H, Krell D, Bielau H, Bogerts B, Bernstein HG. Evidence for structural abnormalities of the human habenular complex in affective disorders but not in schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2010;40:557–567. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch GJ, Granato M, Haffter P. A polymorphic zebrafish line for genetic mapping using SSLPs on high-percentage agarose gels. Techical Tips Online. 1997:T01208. [Google Scholar]

- Rebagliati MR, Toyama R, Fricke C, Haffter P, Dawid IB. Zebrafish nodal-related genes are implicated in axial patterning and establishing left-right asymmetry. Dev. Biol. 1998;199:261–272. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Seaton MS, Wallace J, Al-Harthi L. Porcupine is not required for the production of the majority of Wnts from primary human astrocytes and CD8+ T cells. PLoS one. 2014;9:e92159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussigné M, Bianco I, Wilson SW, Blader P. Nodal signalling imposes left-right asymmetry upon neurogenesis in the habenular nuclei. Development. 2009;136:1549–1557. doi: 10.1242/dev.034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath K, Rubinstein AL, Cheng AMS, Liang JO, Fekany K, Solnica-Krezel L, Korzh V, Halpern ME, Wright CVE. Induction of the zebrafish ventral brain and floorplate requires cyclops/nodal signaling. Nature. 1998;395:185–189. doi: 10.1038/26020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Nugent AC, Bogers W, Roiser JP, Bain EE, Neumeister A, Zarate CA, Manji HK, Cannon DM, Marrett S, et al. Habenula volume in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF, Talbot WS. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF, Walker C, Kimmel CB. The chinless mutation and neural crest cell interactions in zebrafish jaw development. Development. 1996;122:1417–1426. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada R, Satomi Y, Kurata T, Ueno N, Norioka S, Kondoh H, Takao T, Takada S. Monosaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot WS, Schier AF. Positional cloning of mutated zebrafish genes. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;60:259–286. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B. Antivin, a novel and divergent member of the TGFβ superfamily, negatively regulates mesoderm induction. Development. 1999;126:229–240. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Pflumio S, Fürthauer M, Loppin B, Heyer V, Degrave A, Woehl R, Lux A, Steffan T, Charbonnier XQ, Thisse C. Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis. ZFIN Direct Data Submission. 2001 〈 http://zfin.org 〉 .

- Thisse B, Thisse C. Fast Release Clones: A High Throughput Expression Analysis. ZFIN Direct Data Submission. 2004 〈 http://zfin.org 〉 .

- Toyama R, Kim MH, Rebbert ML, Gonzales J, Burgess H, Dawid IB. Habenular commissure formation in zebrafish is regulated by the pineal gland-specific gene unc119c. Dev. Dynam. 2013;242:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G, Lewellis SW, Wang J, Reynolds E, Nicholson C, Knaut H. Generation and dynamics of an endogenous, self-generated signaling gradient across a migrating tissue. Cell. 2013;155:674–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath H, Carter A, Baldwin P, Molfese D, Salas R. The medial habenula: still neglected. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014;7:931. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vue TY, Aaker J, Taniguchi A, Kazemzadeh C, Skidmore J, Martin D, Martin J, Treier M, Nakagawa Y. Characterization of progenitor domains in the developing mouse thalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;505:73–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. Haploid screens and gamma-ray mutagenesis in the zebrafish: genetics and genomics. In: Detrich HW III, Westerfield M, Zon LI, editors. Methods Cell Biology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. pp. 43–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Nusse R. Wnt proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:1–13. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B-T, Wen S-H, Hwang S-PL, Huang C-J, Kuan Y-S. Control of Wnt5b secretion by Wntless modulates chondrogenic cell proliferation through fine-tuning of fgf3 expression. J. Cell Sci. 2015:jcs–167403. doi: 10.1242/jcs.167403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Houart C, Moens CB. Cloning and embryonic expression of zebrafish neuropilin genes. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2004;4:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Chia J, Canning CA, Jones CM, Bard FA, Vishup DM. WLS retrograde transport to the endoplasmic reticulum during Wnt secretion. Dev. Cell. 2014;29:277–291. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Zhu H, Zhang L, Huang S, Cao J, Ma G, Feng G, He L, Yang Y, Guo X. Wls-mediated Wnts differentially regulate distal limb patterning and tissue morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2012;365:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.