Abstract

Modulation is a cornerstone of optical communication, and as such, governs the overall speed of data transmission. Currently, the two main strategies for modulating light are direct modulation of the excited emitter population (for example, using semiconductor lasers) and external optical modulation (for example, using Mach–Zehnder interferometers or ring resonators). However, recent advances in nanophotonics offer an alternative approach to control spontaneous emission through modifications to the local density of optical states. Here, by leveraging the phase-change of a vanadium dioxide nanolayer, we demonstrate broadband all-optical direct modulation of 1.5 μm emission from trivalent erbium ions more than three orders of magnitude faster than their excited state lifetime. This proof-of-concept demonstration shows how integration with phase-change materials can transform widespread phosphorescent materials into high-speed optical sources that can be integrated in monolithic nanoscale devices for both free-space and on-chip communication.

Erbium ions offer a way to integrate light emitters into silicon electronics, but their radiative decay time is too slow for effective light modulation. Here, the authors use phase changes in vanadium dioxide to enable all-optical modulation more than a thousand times faster than the erbium excited-state lifetime.

Erbium ions offer a way to integrate light emitters into silicon electronics, but their radiative decay time is too slow for effective light modulation. Here, the authors use phase changes in vanadium dioxide to enable all-optical modulation more than a thousand times faster than the erbium excited-state lifetime.

The tunable properties of phase-change materials provide an exciting opportunity to modulate the optical response of optoelectronic devices, potentially at ultrafast speeds1,2,3,4. For example, phase-change materials have been considered as a means to modulate reflection and transmission of nanoscale films and devices5,6,7,8. We propose here a new framework to directly modulate light emission from integrated sources faster than their radiative lifetime. The concept is based on the dynamic manipulation of light through tailoring the local density of optical states (LDOS). Such LDOS engineering can be used to control the direction9, polarization10,11 and spectrum12,13 of light emission, even at sub-lifetime scales14.

Here, we use phase-change materials within an engineered optical environment to dynamically control the spontaneous light emission of a quantum emitter. We leverage the ultrafast insulator-to-metal transition (IMT) of vanadium dioxide (VO2)2,3,4 as well as the symmetry difference in the polarization of electric dipole (ED) and magnetic dipole (MD) transitions of erbium ions to demonstrate direct all-optical modulation of spontaneous emission at sub-lifetime scales. Distinct from direct ‘electronic' modulation of off-chip III-V based lasers15,16,17 or optical modulation using external interferometers18,19,20, this approach enables both the emitter and modulator to be monolithically integrated into a single nanoscale device.

Results

Design

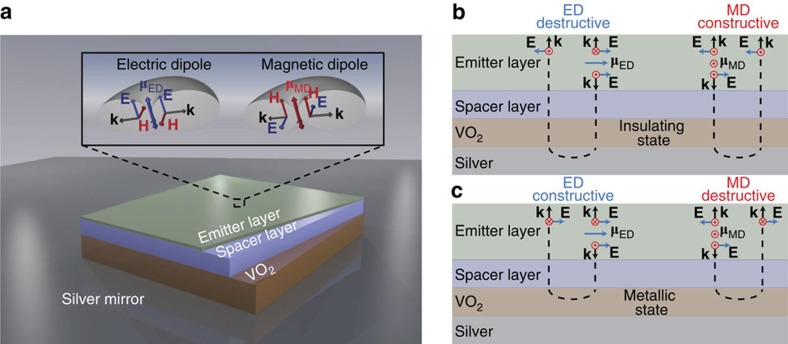

The key to realizing optical modulation is to design a multilayer structure such that the phase-change layer can be externally switched by a control laser while also having maximum influence on the LDOS of the emitter layer. A simple design to achieve this goal is a quarter-wavelength phase-change layer (that is, thickness  where n is the refractive index) located between an emitter layer and a metal mirror, as shown in Fig. 1a. If the stack is constructed in this way, there is a

where n is the refractive index) located between an emitter layer and a metal mirror, as shown in Fig. 1a. If the stack is constructed in this way, there is a  phase shift in the effective optical path length when the VO2 is switched from the insulating to metallic state (Fig. 1b,c), which maximizes the influence of the phase-change on the surrounding LDOS.

phase shift in the effective optical path length when the VO2 is switched from the insulating to metallic state (Fig. 1b,c), which maximizes the influence of the phase-change on the surrounding LDOS.

Figure 1. Sketch of the sample and illustration of LDOS modulation.

(a) Sketch of the sample. Inset shows the polarization symmetries of ED and MD radiation. (b,c) illustrate the interference of ED and MD emission processes when the VO2 layer is in the insulating and metallic phases, respectively.

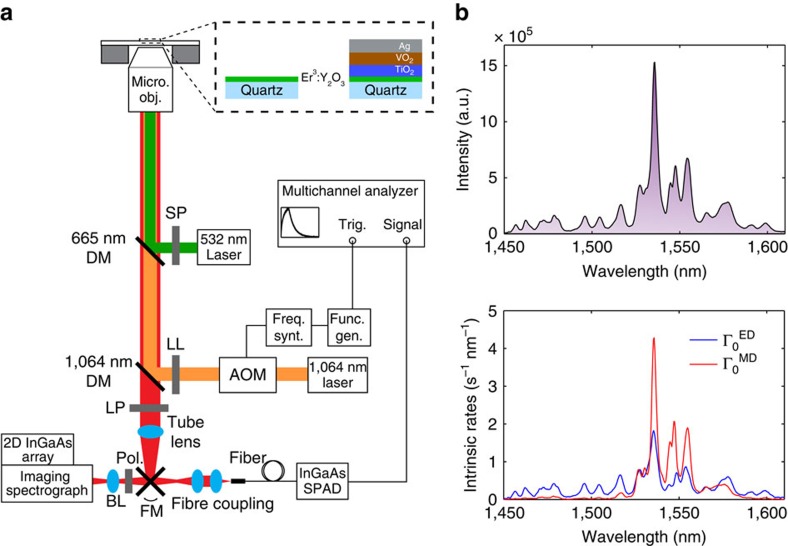

As the process of light emission depends both on the optical environment and on the intrinsic properties of the emitter, engineering spontaneous emission also requires knowledge of the underlying electronic transitions (that is, emission wavelength and dipolar nature). The emission from erbium at 1.5 μm has a multipolar character, showing equal contributions from ED and MD transitions13,21. Using the energy-momentum spectroscopy set-up shown in Fig. 2a, we can precisely quantify the intrinsic radiative rates of ED and MD transitions in a thin film of Er3+:Y2O3 (refs 13, 22; Supplementary Fig. 1). The results of this analysis illustrate how the photoluminescence spectrum (shown in Fig. 2b) originates from a combination of spectrally distinct ED and MD transitions (shown in Fig. 2c)13. These two kinds of transitions typically present differing field symmetries: ED emit with symmetric electric fields, while MD emit with antisymmetric electric fields (Fig. 1c). This symmetry difference can be leveraged to dynamically enhance (or suppress) their emission by modifying the electric and magnetic LDOS via the VO2 IMT and therefore switch between these distinct spectra.

Figure 2. Experimental set-up and ED/MD contributions to Er3+ emission around 1.5 μm.

(a) Experimental set-up used for conventional photoluminescence, energy-momentum spectroscopy and time-resolved measurements. (b) Photoluminescence spectrum of a single-layer Er3+:Y2O3 sample. (c) Extracted spectrally resolved intrinsic emission rates for ED (blue) and MD (red) transitions obtained from theoretical fit to experimental energy-momentum spectra (Supplementary Fig. 1). AOM, acousto-optic modulator; BL, Bertrand lens; DM, dichroic mirror; FM, flip mirror; freq. synt., frequency synthesizer; func. gen., function generator; LL, laser line; micro. obj., microscope objective; Pol, polarization; SP, short-pass; SPAD, single-photon avalanche photodiode; trig., trigger.

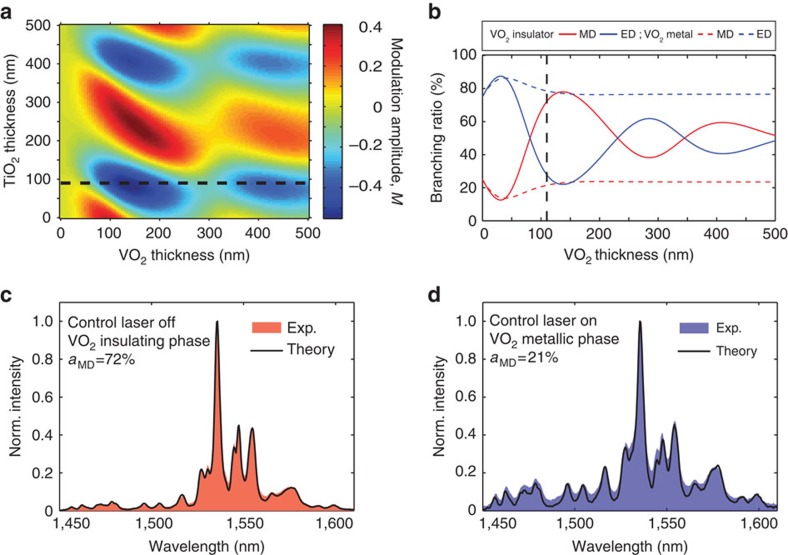

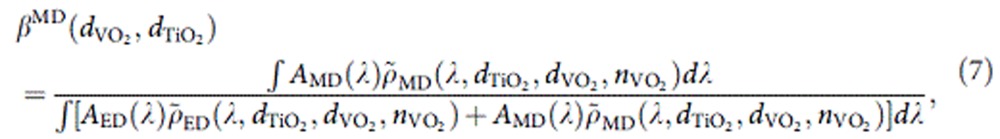

To this end, we design a multilayer structure (Fig. 1) that comprises an Er3+:Y2O3 thin-film emitter, a TiO2 spacer layer, a VO2 layer and an Ag mirror. (Expressions for the LDOS in such a five-layer system are explicitly provided in Supplementary Note 1 together with a related schematic in Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 3a shows the calculated modulation amplitude of MD emission as a function of the thicknesses of both VO2 and TiO2 layers, where  and

and  denotes the Er3+ MD branching ratio for the different phases of VO2 (more details in Methods section).

denotes the Er3+ MD branching ratio for the different phases of VO2 (more details in Methods section).

Figure 3. Device design and spectral modulation of Er3+ emission in multilayer structure.

(a) 2D colour plot of the calculated modulation amplitude of the MD contribution to Er3+ emission at 1.5 μm upon the VO2 phase-change, as a function of TiO2 and VO2 thicknesses. (b) Evolution of the branching ratio of ED (red) and MD (blue) emission as a function of the VO2 thickness (where  as indicated by the black line in a), before (solid lines) and after (dashed lines) inducing the VO2 insulator-to-metal transition. The black line labels the VO2 thickness used in our experiment. (c,d) Experimental and calculated spectra for Er3+ ions when VO2 is in the (c) insulating state and (d) metallic state. Experimental spectra are shown in shaded red and blue colour, respectively, whereas theoretically predicted spectra are shown as black solid lines. Exp, experimental; norm, normalized.

as indicated by the black line in a), before (solid lines) and after (dashed lines) inducing the VO2 insulator-to-metal transition. The black line labels the VO2 thickness used in our experiment. (c,d) Experimental and calculated spectra for Er3+ ions when VO2 is in the (c) insulating state and (d) metallic state. Experimental spectra are shown in shaded red and blue colour, respectively, whereas theoretically predicted spectra are shown as black solid lines. Exp, experimental; norm, normalized.

Switching ED and MD emission using VO2

As can be seen in Fig. 3a, specific conditions enable the complete reversal of the emission from dominantly MD to dominantly ED (and vice-versa) upon switching of VO2. To experimentally investigate this direct modulation of Er3+ light emission induced by the VO2 phase-change, we fabricated a multilayer structure with  and

and  . For this particular geometry, the device is designed such that the emitter layer has a high magnetic LDOS when VO2 is in the insulating state, but switches to a high electric LDOS when VO2 is in the metallic state as shown in Fig. 3b.

. For this particular geometry, the device is designed such that the emitter layer has a high magnetic LDOS when VO2 is in the insulating state, but switches to a high electric LDOS when VO2 is in the metallic state as shown in Fig. 3b.

The shaded curve in Fig. 3c shows the measured spectrum of the sample when continuously pumped by a 532 nm laser. As expected, the spectrum resembles that of dominantly MD emission (as can be seen by comparison to the intrinsic MD rate in Fig. 2c). Then, using a 1,064 nm control beam, we independently trigger the VO2 phase-change and demonstrate all-optical modulation of the local optical environment as well as the resulting emission. (Note that the 1,064 nm control laser is chosen to be non-resonant with any Er3+ transitions). Figure 3d shows the resulting Er3+ emission spectrum under illumination by both the 1,064 nm control laser and 532 nm pump laser and we see a clear difference in the resulting spectrum. As compared with Fig. 3c, the spectra in Fig. 3d shows the rise of distinct emission peaks between 1,450 and 1,520 nm, which indicates a switch from dominantly MD emission to dominantly ED emission (more details in the Supplementary Fig. 3). This is more clearly evidenced in Fig. 4a where the experimental Er3+ spectra obtained for insulating and metallic VO2 are displayed together. In addition, when the 1,064 nm laser control beam is turned back off, the Er3+ emission returns to its initial spectral shape.

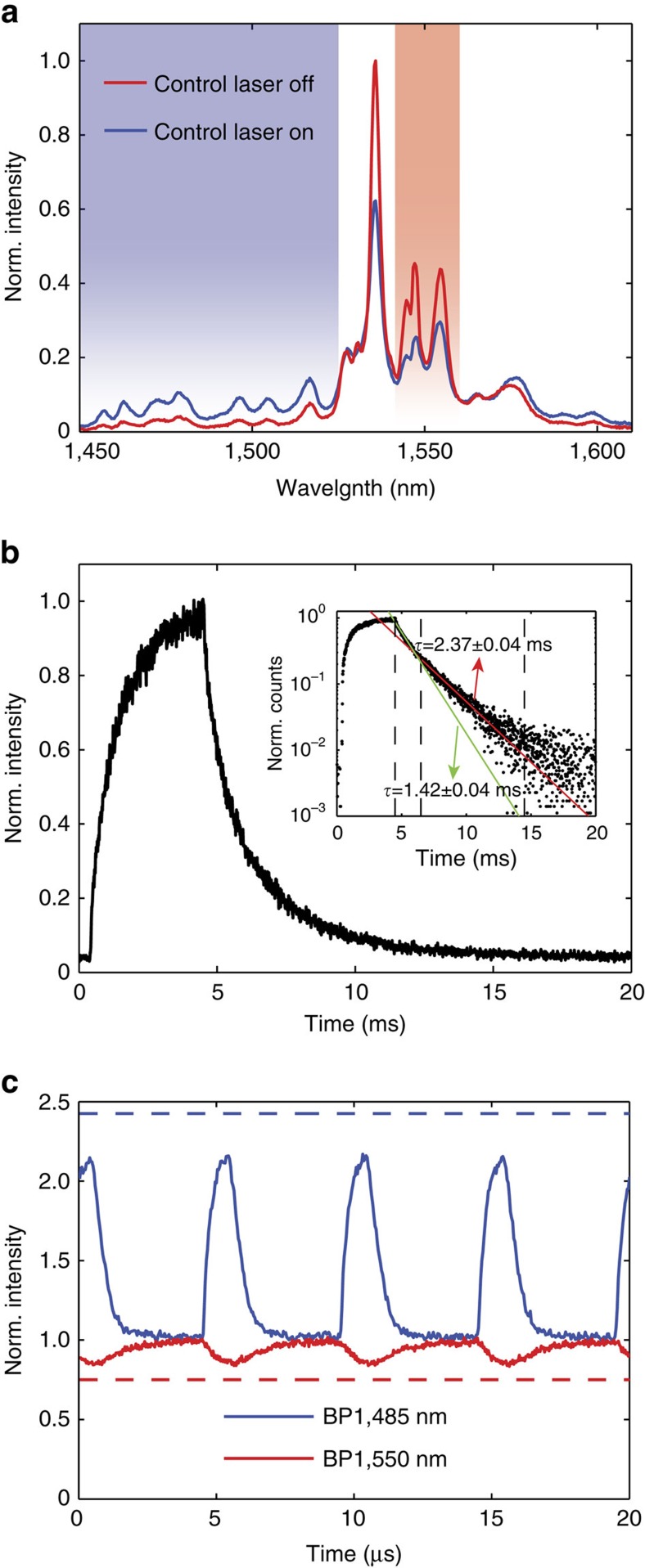

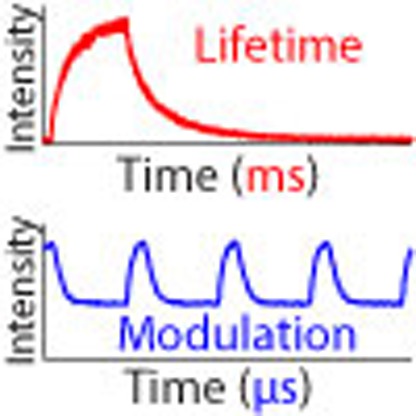

Figure 4. Sub-lifetime modulation of Er3+ light emission.

(a) Experimental spectra for Er3+ ions when VO2 is in the insulating state (red) and in the metallic state (blue). (b) Decay trace of the time-resolved photoluminescence intensity from Er3+ ions subjected to a pulsed 532 nm excitation. Inset shows lifetime fits, showing both fast (green) and slow (red) decay contributions with lifetimes of  and

and  , respectively. (c) Time-resolved normalized photoluminescence of the Er3+ ions in the multilayer structure when continuously pumped by a 532-nm laser while VO2 is simultaneously switched by a pulsed 1,064 nm excitation at a 200 kHz repetition rate. Note the three orders of magnitude difference in the time-scale for c as compared with b. Blue and red solid lines represent two different spectral ranges of the bandpass (BP) filters (1,450–1,520 nm and 1,538–1,562 nm, respectively). The dashed lines show the theoretical maximum modulation calculated according to the spectra in a.

, respectively. (c) Time-resolved normalized photoluminescence of the Er3+ ions in the multilayer structure when continuously pumped by a 532-nm laser while VO2 is simultaneously switched by a pulsed 1,064 nm excitation at a 200 kHz repetition rate. Note the three orders of magnitude difference in the time-scale for c as compared with b. Blue and red solid lines represent two different spectral ranges of the bandpass (BP) filters (1,450–1,520 nm and 1,538–1,562 nm, respectively). The dashed lines show the theoretical maximum modulation calculated according to the spectra in a.

From the measured intrinsic rates (Fig. 2c) and the optical properties (that is, thickness and refractive index of individual layers), we can theoretically predict the normalized photoluminescence spectrum as a function of the VO2 state (see Methods section and Supplementary Fig. 4). Using the measured refractive indices of VO2 in the insulating state, as shown in Fig. 3c, the theoretical prediction (black line) matches well with the experimental spectrum without 1,064 nm laser illumination (shaded red area). For the insulating state, these calculations indicate that ∼70% of the total emission originates from MD transitions. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3d, when we use the measured refractive indices of VO2 in the metallic state, we accurately predict the experimental spectrum obtained under 1,064 nm illumination. In the metallic state, the calculations suggest that MD transitions account for a much smaller percentage of emission (∼21%) and the vast majority of emission (∼79%) originates from ED transitions.

Modulating spontaneous emission faster than lifetime limit

We have therefore experimentally demonstrated that light emission from Er3+ ions around 1.5 μm can be controllably switched from MD-dominant emission to ED-dominant emission. The result of this tuning is a significant modulation of the spectral shape, intensity and polarization of light emission. But the two most important implications of using a phase-change material to modulate light emission are the following: (i) The resulting modulation is broadband: in this experiment it covers the S-, C- and L-bands of conventional fibre-optic communication. Furthermore, given the ultra-broadband tuning of VO2 refractive index (Supplementary Fig. 5), the modulation range can easily be extended to shorter wavelengths (down to ∼500 nm). (ii) This all-optical switching exploits modifications to the LDOS rather than pumping on and off the electronic system governing light emission (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). There is a fundamental difference in the time-scales of these two processes. For example when Er3+ ions are subjected to a pulsed excitation, the time-scale of the decay process is intrinsically limited by the long lifetime of the emitters. This is clearly evidenced in Fig. 4b, where full decay of photoluminescence from the 4I13/2 excited state requires almost 10 ms. On the other hand, if we use the 532 nm laser as a continuous excitation source and a pulsed 1,064 nm laser to dynamically switch the VO2 phase, we can modulate the emission much faster than the decay time of Er3+.

Figure 4c presents the normalized time-resolved photoluminescence in two wavelength ranges of interest: the S-band (1,450–1,520 nm; ED-dominant, blue line) and the C-band (1,540–1,560 nm; MD-dominant, red line) when the 1,064 nm control laser is chopped by an acousto-optic modulator (AOM) at a repetition rate of 200 kHz (see Fig. 2a for a schematic of the set-up and Methods for a detailed description of the measurements). We are able to clearly modulate light emission at time-scales more than three orders of magnitude faster than the lifetime of Er3+ ions. (Note that without the VO2 layer, no modulation is observed). In addition, we observe that when the S-band ED-emission (blue line) is enhanced, the C-band MD-emission (red line) is simultaneously suppressed: a clear indication that the modulated emission is consistent with the linked ED and MD LDOS changes. Note that the observed intensity modulation ratio of 2:1 results from our use of spectrally mixed ED and MD transitions. Even when switching from strongly MD emission (72% MD) to strongly ED emission (21% MD), the resulting intensity modulation will be lower than the average rate change (for example, 72%/21%), because ED and MD emission is mixed throughout the wavelength region of interest. One could achieve greater modulation depths by leveraging further differences beyond spectral intensity, such as the differing phase and polarization symmetries of ED and MD emission22. For example, the  -phase shift between ED and MD transitions could be used for differential phase shift keying modulation23.

-phase shift between ED and MD transitions could be used for differential phase shift keying modulation23.

Discussion

We expect the fundamental limit on the speed of modulation to be significantly faster than this initial demonstration. In our experiment, the speed of switching is mainly limited by the AOM used to modulate the 1,064 nm control laser. In theory, dynamic modulation of emission through tuning the LDOS is only limited by retardation effects (that is, the time needed for light to propagate from the emitter to the reflecting layer and back). Therefore, the proposed device should allow modulation speeds approaching the time-scale of the IMT of VO2, which may be as fast as a few hundreds of femtoseconds2,3. The ultimate switching speed of our device could be tested in future studies by using an ultrafast laser (for example, Ti:Sapphire) to switch VO2 (refs 2, 4), while continuously pumping Er ions and monitoring their luminescence. Alternatively, one could electrically modulate the VO2 layer to eliminate the need for ultrafast lasers and, in turn, investigate device performance in a more practical operating mode.

Using phase-change media such as VO2 to dynamically control spontaneous emission allows for complete device integration onto a single chip. Such a monolithic and heterogeneous integration is demonstrated here for the first time. Moreover, the use of phase-change materials dramatically increases the speed of LDOS modulation by orders of magnitude over initial mechanical approaches using piezoelectrically actuated mirrors14. Dynamic modulation of spontaneous emission in this monolithic nanoscale device could potentially reach ultrafast speeds, up to the phase transition kinetics of VO2.

The presented device has a very simple geometry: it is composed of a stack of planar nanolayers. (See Supplementary Fig. 8 for demonstration of sub-lifetime modulation of Er3+ emission using a different multilayer stack with a silicon spacer and gold mirror.) Although the respective thicknesses are crucial for engineering the modulation amplitude, there are no restrictions on the lateral dimensions. Indeed, in this experiment, both laser beams were confined to a diffraction-limited spot. Such a device could therefore easily be integrated on a variety of structures including cavities, waveguides and light-emitting devices. While this initial demonstration focused on all-optical modulation, switching of VO2 could also be produced by electrically triggering the IMT24,25 (see Supplementary Note 2 for discussion of switching energy). Combined with electroluminescent devices26,27, all-electrical direct modulation of emission could be obtained. The presented concept is not limited to Er3+ ions and VO2. Indeed, the dynamic modulation of the LDOS could be extended to any phase-change material which experiences a large change in optical properties1,5,7,28 and any emitters with spectrally close ED and MD transitions. Such emitters include both lanthanide14,21 and transition-metal doped materials29,30 that are widely used as phosphors in solid-state light sources. We therefore hope that the device and concept presented here will engage both academic and industrial researchers working on optoelectronics and nanophotonics.

Methods

Device fabrication

A 145-nm-thick Y2O3 buffer-layer was deposited by e-beam evaporation followed by a 50-nm-thick Er3+:Y2O3 thin-film emitter and covered by a ∼5-nm Y2O3 layer. The sample was then annealed for 1 h at 900 °C under a flux of O2 (0.5 lpm) to both activate the Er3+ ions and crystallize the Y2O3. A TiO2 spacer layer was subsequently deposited by reactively sputtering a pure titanium target under a controlled O2/Ar ratio (5%/95%). A low-temperature anneal (500 °C, 0.5 lpm O2) was carried out to homogenize the TiO2 layer. On top of this spacer layer, VO2 was deposited by sputtering a V2O5 target under a partial atmosphere of O2/Ar (0.08 sccm O2 and 49.92 sccm Ar) while maintaining the substrate at 550 °C (ref. 24). Finally, a 200-nm silver layer was sputtered from a pure Ag target under an atmosphere of pure argon. All layer thicknesses, except the VO2 layer, were monitored in situ using a quartz microbalance. All refractive indices and thicknesses were measured after deposition by ellipsometry.

Experimental set-up

The conventional photoluminescence spectrum of the sample was obtained using an inverted microscope in which an oil immersion ( × 100, 1.3 NA) objective was used for both excitation of the sample and collection of light emission. Er3+ ions were pumped using a 532-nm frequency-doubled Nd:YVO4 laser (Coherent Verdi). The laser line and emission from the sample were separated by a 665-nm dichroic mirror. The near-infrared emission was directed to an imaging spectrograph (IsoPlane SCT 320), subsequently dispersed (grating with 300 lines per mm blazed at 1.2 μm) and detected by a 2D InGaAs detector array (NIRvana, Princeton Instruments). Measured data have been corrected for the spectral and polarization dependence of the optical set-up using a calibrated quartz tungsten halogen lamp (Newport, Oriel 63355).

For energy-momentum spectroscopy, a 100-mm Bertrand lens was used to image the back focal plane of the objective and thus project the radiation pattern of emission onto the entrance slit of the spectrograph. Using a rotatable polarizer, s- and p-polarized back focal plane spectra were then obtained by imaging the energy- and momentum-resolved photoluminescence on the 2D NIR camera. The all-optical modulation experiment was performed by focusing a 1,064-nm laser on the sample through the same × 100 objective. The laser line was filtered out by a 1,064-nm dichroic mirror and a 1,064-nm long pass filter. Precise coalignment of the 532 nm and the 1,064-nm lasers was enabled by using an eyepiece camera to monitor the position of their respective foci. Spectra of Er3+:Y2O3 with VO2 in the insulating and metallic states were obtained similarly to the photoluminescence set-up described above, by simply turning on and off the 1,064 nm laser. Time-resolved photoluminescence was acquired by a time-gated fiber-coupled InGaAs/InP single-photon avalanche photodiode, and a multichannel analyser (Stanford Research System 430) was used to build a histogram of photon arrival times. For conventional lifetime measurements of Er3+ ions, the 532 nm laser was modulated by a mechanical chopper at a frequency of 38 Hz. Dynamic modulation of the LDOS through VO2 switching was carried out by chopping the 1,064 nm laser with an AOM. Two long pass filters (1,350 nm and 1,450 nm) were cascaded (total OD 10) and systematically used to block the laser line at the entrance of the single-photon avalanche photodiode, and additional bandpass filters were used to measure specific wavelength ranges.

Quantification of intrinsic emission rates

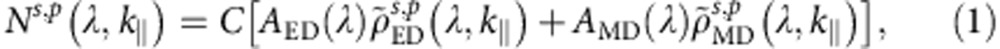

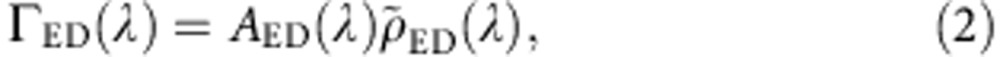

To determine the intrinsic ED and MD emission rates, we measured the energy-momentum spectra of the Er3+:Y2O3 emitter layer on quartz in a region without the TiO2/VO2/Ag overcoat layers (Supplementary Fig. 1). With this technique, we measure the distribution of light emission from Er3+ as a function of wavelength  and in-plane momentum (k||). Using the procedure first described in Taminiau et al.22, experimental energy-momentum cross-sections in this three-layer system were fit to:

and in-plane momentum (k||). Using the procedure first described in Taminiau et al.22, experimental energy-momentum cross-sections in this three-layer system were fit to:

|

where C is an overall scaling factor to account for experimental parameters that influence the number of measured counts but do not affect the radiation pattern.  and

and  are the normalized LDOS for a three-layer system calculated using equations in the Supplementary Information (S11–S14) of ref. 22. (Note that the three-layer LDOS expressions may be readily derived from the five-layer system expressions provided in Supplementary Note 1 by setting n0=n1=n2=1). Using equation (1), we can fit the energy-momentum spectra to extract the spectrally resolved Einstein A coefficients (AED and AMD). These coefficients, shown in Fig. 2c, represent the relative ED and MD intrinsic radiative rates at each wavelength, and are proportional to the intrinsic rates that one would expect in a homogeneous medium.

are the normalized LDOS for a three-layer system calculated using equations in the Supplementary Information (S11–S14) of ref. 22. (Note that the three-layer LDOS expressions may be readily derived from the five-layer system expressions provided in Supplementary Note 1 by setting n0=n1=n2=1). Using equation (1), we can fit the energy-momentum spectra to extract the spectrally resolved Einstein A coefficients (AED and AMD). These coefficients, shown in Fig. 2c, represent the relative ED and MD intrinsic radiative rates at each wavelength, and are proportional to the intrinsic rates that one would expect in a homogeneous medium.

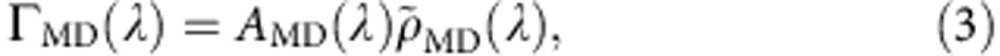

Theoretical calculation of modified emission spectra

To predict how the Er3+ emission spectrum will be modified by the VO2 phase-change, we use the measured intrinsic emission rates,  and

and  , inferred from the three-layer, emitter-on-substrate system together with the theoretically calculated LDOS for the five-layer device structure (described in Supplementary Note 1). The product of the intrinsic emission rate with the appropriate integrated LDOS yields the radiative decay rate for electric and magnetic transitions:

, inferred from the three-layer, emitter-on-substrate system together with the theoretically calculated LDOS for the five-layer device structure (described in Supplementary Note 1). The product of the intrinsic emission rate with the appropriate integrated LDOS yields the radiative decay rate for electric and magnetic transitions:

|

|

where the LDOS is integrated in momentum over the range of values collected by the numerical aperture (NA) of our imaging system:

|

and

|

Note that in equations (4 and 5) we integrate over a line in momentum-space, which is consistent with the experimental set-up where the spectrum is collected after a Bertrand lens through a narrow slit spectrometer.

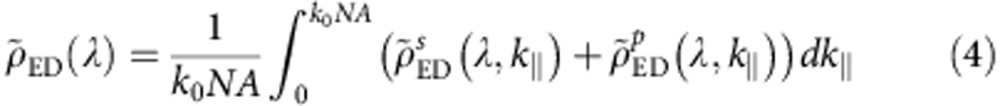

The intensity of emitted light is proportional to the total emission rate,  . Therefore, the theoretical normalized intensity can be calculated as follows:

. Therefore, the theoretical normalized intensity can be calculated as follows:

|

where Imax and Γmax denote the maximum values of the light intensity and the total emission rate near 1.5 μm, respectively. Using equations (2, 3, 4, 5, 6), we can calculate the predicted emission spectrum of Er3+ for both phases of VO2. As can be seen in Fig. 3c,d, there is an excellent agreement between the predicted and measured spectra. For reference, Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the calculated spectra (black line) decomposed into ED (shaded blue area) and MD (shaded red area) contributions.

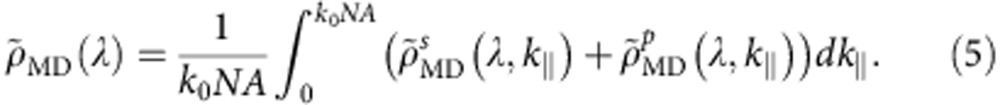

Simulation of branching ratios

To quantify the fraction of light emission that originates from MD or ED transitions, we define branching ratios ( and

and  ) as a function of the TiO2 spacer layer thickness

) as a function of the TiO2 spacer layer thickness  and VO2 layer thickness

and VO2 layer thickness  :

:

|

where  is the phase-dependent refractive index of VO2. In our calculations, we use wavelength-dependent data for VO2 at 25 and 95 °C measured by Jianing Sun of the J.A. Woollam Company to model the insulating and metallic phases, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). For the complex refractive index of the silver layer, we use the Lorentz–Drude model in Rakić et al.31.

is the phase-dependent refractive index of VO2. In our calculations, we use wavelength-dependent data for VO2 at 25 and 95 °C measured by Jianing Sun of the J.A. Woollam Company to model the insulating and metallic phases, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). For the complex refractive index of the silver layer, we use the Lorentz–Drude model in Rakić et al.31.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Cueff, S. et al. Dynamic control of light emission faster than the lifetime limit using VO2 phase-change. Nat. Commun. 6:8636 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9636 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge fruitful discussion with S. Karaveli, C.M. Dodson and M. Jiang. Financial support was provided by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-10-1-0026 and FA9550-12-1-0189), Army Research Office (W911NF-14-1-0669), Department of Education (P200A090076) and National Science Foundation (EECS-0846466 and EECS-1408009).

Footnotes

Author contributions S.C. and R.Z. conceived the idea and designed the experiment. S.C., D.L., J.A.K. and R.Z. designed the structures and performed the optical experiment. S.C. and D.L. fabricated and optimized the emitting and spacer layers. Y.Z., F.J.W. and S.R. fabricated and characterized the VO2 layers. All authors helped to improve the manuscript.

References

- Loke D. et al. Breaking the speed limits of phase-change memory. Science 336, 1566–1569 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalleri A. et al. Femtosecond structural dynamics in VO2 during an ultrafast solid-solid phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 237401 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appavoo K. et al. Ultrafast phase transition via catastrophic phonon collapse driven by plasmonic hot-electron injection. Nano Lett. 14, 1127–1133 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysenko S., Rúa A., Vikhnin V., Fernández F. & Liu H. Insulator-to-metal phase transition and recovery processes in VO2 thin films after femtosecond laser excitation. Phys. Rev. B 76, 035104 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini P., Wright C. D. & Bhaskaran H. An optoelectronic framework enabled by low-dimensional phase-change films. Nature 511, 206–211 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kats M. A. et al. Ultra-thin perfect absorber employing a tunable phase change material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 221101 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Samson Z. et al. Metamaterial electro-optic switch of nanoscale thickness. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 143105 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman J. D., Hallman K. A., Marvel R. E., Haglund R. F. & Weiss S. M. Ultra-compact silicon photonic devices reconfigured by an optically induced semiconductor-to-metal transition. Opt. Express 21, 10753–10763 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curto A. G. et al. Unidirectional emission of a quantum dot coupled to a nanoantenna. Science 329, 930–933 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauf S. et al. High-frequency single-photon source with polarization control. Nat. Photon. 1, 704–708 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Noda S., Yokoyama M., Imada M., Chutinan A. & Mochizuki M. Polarization mode control of two-dimensional photonic crystal laser by unit cell structure design. Science 293, 1123–1125 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaveli S. & Zia R. Spectral tuning by selective enhancement of electric and magnetic dipole emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 193004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. et al. Quantifying and controlling the magnetic dipole contribution to 1.5-μm light emission in erbium-doped yttrium oxide. Phys. Rev. B 89, 161409 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Karaveli S., Weinstein A. J. & Zia R. Direct modulation of lanthanide emission at sub-lifetime scales. Nano Lett. 13, 2264–2269 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y., Murai H., Arahira S., Kutsuzawa S. & Ogawa Y. 30-GHz bandwidth 1.55-μm strain-compensated InGaAlAs-InGaAsP MQW laser. Photon. Technol. Lett. IEEE 9, 25–27 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Kjebon O. et al. 30 GHz direct modulation bandwidth in detuned loaded InGaAsP DBR lasers at 1.55 μm wavelength. Electron. Lett. 33, 488–489 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Mohrdiek S. et al. 10-Gb/s standard fiber transmission using directly modulated 1.55-μm quantum-well DFB lasers. Photon. Technol. Lett. IEEE 7, 1357–1359 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. et al. A high-speed silicon optical modulator based on a metal-oxide-semiconductor capacitor. Nature 427, 615–618 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Schmidt B., Pradhan S. & Lipson M. Micrometre-scale silicon electro-optic modulator. Nature 435, 325–327 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed G. T., Mashanovich G., Gardes F. & Thomson D. Silicon optical modulators. Nat. Photon. 4, 518–526 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Dodson C. M. & Zia R. Magnetic dipole and electric quadrupole transitions in the trivalent lanthanide series: calculated emission rates and oscillator strengths. Phys. Rev. B 86, 125102 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Taminiau T. H., Karaveli S., van Hulst N. F. & Zia R. Quantifying the magnetic nature of light emission. Nat. Commun. 3, 979 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer P. J. & Essiambre R.-J. Advanced optical modulation formats. Proc. IEEE 94, 952–985 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. Voltage-triggered ultrafast phase transition in vanadium dioxide switches. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 220–222 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Joushaghani A. et al. Electronic and thermal effects in the insulator-metal phase transition in VO2 nano-gap junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 231904 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cueff S. et al. Structural factors impacting carrier transport and electroluminescence from Si nanocluster-sensitized Er ions. Opt. Express 20, 22490–22502 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueff S. et al. Electroluminescence efficiencies of erbium in silicon-based hosts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 191109 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhou Y. & Ramanathan S. Colossal resistance switching and band gap modulation in a perovskite nickelate by electron doping. Nat. Commun. 5, 4860 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaveli S., Wang S., Xiao G. & Zia R. Time-resolved energy-momentum spectroscopy of electric and magnetic dipole transitions in Cr3+: MgO. ACS Nano 7, 7165–7172 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaveli S., Li D. & Zia R. Probing the electromagnetic local density of states with a strongly mixed electric and magnetic dipole emitter. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1311.0516 (2013).

- Rakić A. D., Djurišic A. B., Elazar J. M. & Majewski M. L. Optical properties of metallic films for vertical-cavity optoelectronic devices. Appl. Opt. 37, 5271–5283 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References