Abstract

Introduction:

Hair loss is a common and distressing problem that can affect both males and females of all ages. Chronic telogen effluvium (CTE) is idiopathic diffuse scalp hair shedding of at least 6 months duration. Hair loss can be one of the symptoms of metal toxicity. Lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) are highly toxic metals that can cause acute and chronic health problems in human. The aim of the present study is to determine if there is a relationship between these metals and CTE in women and if CTE is also associated with changes in zinc (Zn) or iron (Fe) blood levels.

Materials and Methods:

Pb, Cd, Fe and Zn total blood levels were determined in 40 female patients fulfilling the criteria of CTH and compared with total blood levels of same elements in 30 well-matched healthy women.

Results:

Quantitative analysis of total blood Fe, Zn, Pb and Cd revealed that there were no significant differences between patients and controls regarding Fe, Zn, and Pb. Yet, Cd level was significantly higher in patients than controls. In addition, Cd level showed significant positive correlation with the patient's body weight.

Conclusion:

Estimation of blood Pb and Cd levels can be important in cases of CTE as Cd toxicity can be the underlying hidden cause of such idiopathic condition.

Keywords: Cadmium, hair loss, iron, lead, telogen effluvium, zinc

INTRODUCTION

Hair is considered as one of the most defining aspects of human appearance. Alopecia or hair loss is a common and distressing problem that has a significant impact on quality of life. It is often met with feelings of grief, loss of self-confidence, and low self-esteem.[1] Physicians should not underestimate the emotional effects of hair loss. About 40% of patients felt dissatisfied with the way in which their doctor dealt with them.[2]

Telogen effluvium (TE) is the most common form of hair loss.[3] It is caused by any disruption of hair growth cycle resulting in increased synchronized telogen hair shedding.[4] Acute TE is an acute onset scalp hair loss occurring 2–3 months after a triggering event, which can be unidentifiable in up to 33% of cases.[5] Chronic diffuse telogen hair loss denotes to telogen hair shedding, longer than 6 months, secondary to a diversity of organic causes.[3] Chronic TE (CTE) is a primary or idiopathic generalized shedding of telogen hairs from the scalp lasting more than 6 months without any apparent cause.[6,7] It is characterized by insidious onset and a fluctuating course. On examination, the hair appears normal in thickness with shorter re-growing hairs in the frontal and bitemporal areas, and hair pull test is commonly positive.[3]

Several studies have evaluated the relationship between iron (Fe) deficiency and hair loss. Almost all of them focused exclusively on women, and some suggested that Fe deficiency even in the absence of anemia might cause TE,[8,9,10] yet, others have challenged this viewpoint.[11,12,13,14] Zinc (Zn) deficiency may cause TE, and its supplementation may terminate the disorder.[10,15,16] There is an opposing argument that there exists no relationship between Zn and TE so far.[3,5,9,17]

It was reported that many heavy metals (thallium, mercury, arsenic, copper, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and bismuth) are capable of disrupting the formation of hair shaft through covalent bonding with the sulfhydryl groups in keratin.[18] Pb and Cd are highly toxic metals and both are prevalent in the environment and accumulate in the body over lifetime.[19]

Several studies reported increased levels of toxic heavy metals in the Egyptian environment. It was reported that Cd and Pb contents in some foodstuffs from the Egyptian market were above the acceptable levels as established by the regulatory organizations.[20] In addition, Cd and Pb concentrations in surface drinking water samples of Dakahlia Governorate were higher than the permissible limits of Egyptian Ministry of Health and World Health Organization (WHO).[21] In addition, water, sediments, and fish organs from Lake Manzala in Dakahlia Governorate showed high concentrations of Cd and Pb above the international permissible limits in water and sediment quality guidelines, and fish might pose health hazards for consumers.[22]

By reviewing the literature, there was no enough study for the association between exposure to toxic heavy metals and hair loss. Also, there is still a debate about the association between changes in Fe and Zn blood levels and hair loss. The aim of the present work is to determine whether there is a relationship between CTE in females and alterations in Pb, Cd, Zn, and Fe blood levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of patients and controls

This case-control study was conducted on the patients attending the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic of Mansoura University Hospital, Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt. This study was in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Consent was obtained from each participant before entering the study.

This work included 40 female patients having CTE and 30 healthy well-matched females as a control group. Detailed history was taken regarding age, occupation, marital status, pregnancy and lactation, special habits, scarves wearing, hair loss history including duration of the disease, associated psychological disturbances, associated medical or surgical conditions, and drug intake. Complete general and dermatological examinations were done. Hair pull test for evaluation of hair loss was done as following: No shampooing hair 24 h prior to the test, then about 60 hairs were grasped between thumb and fingers and pulled gently but firmly from root to tip. The test was repeated in all four quadrants of the scalp and bitemporal areas. The test considered positive when more than 10% of hair pulled out indicating a process of active hair shedding.[23]

All contributors were nonworking females living in Dakahlia Governorate with no special habit. Clinically, all the patients showed CTE that is characterized by a diffuse loss of telogen hairs involving the whole scalp and continuing for more than 6 months. The hairs appeared normal in thickness, with shorter re-growing hairs in the frontal and bitemporal areas. Hair pull test was positive all-over scalp (in both the vertex area, margins of the scalp, and the occipital region) in all cases. In addition, trichogram (microscopic evaluation of hairs) revealed hairs of homogeneous thickness in telogen phase with club-shaped roots.

Trichoscopy was used to exclude other causes of hair loss as there are no exact trichoscopy findings in CTE. However, frequent, but not specific, findings include the presence of empty hair follicles/yellow dots, a predominance of follicular units with only one hair, perifollicular discoloration (the peripilar sign), upright re-growing hairs and lack of features typical of other diseases. There is no significant difference between the findings in the frontal area and those in the occipital area.

Routine investigations for all contributors including complete blood picture, random blood sugar, liver and kidney functions, and thyroid hormones (in suspected cases) were done, and they were normal.

We excluded, in the current study, any female with identifiable causes of hair loss such as recent abortion, pregnancy, lactation, anemia, hyperandrogenism (e.g. PCOS & androgenetic alopecia), thyroid dysfunction, major chronic illness (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, hepatic, or renal diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus), diet regime, nutritional deficiency, procedures for hair (e.g. dyeing, waving) and history of operation. We also excluded patients on the following drugs: Chemotherapy, anticonvulsant, anti-coagulants, antidepressants, any hormonal treatment such as estrogens, progesterone, androgen or thyroxin, antigout, antihypertensive, and Fe or Zn supplement.

Biochemical analysis of lead, cadmium, iron, and zinc

For each participant, after the skin was cleaned with 70% ethanol, 1 mL venous blood was withdrawn from anticubital vein under complete aseptic condition using disposable plastic syringes, transferred into polypropylene tube and kept in the refrigerator at −20°C till conduction of analysis of Pb, Cd, Fe, and Zn. Digestion of blood samples were done by the wet method of digestion (nitric-perchloric acid) according to the method of Vanloon.[24] Pb, Cd, Fe, and Zn quantitative analysis was done according to the method of Stockwell and Corns[25] using Perkin-Elmer 2380 atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS cold steam technique in combination with flow injection system at Mansoura Faculty of Science).

Preparation of standards and samples was carried out under clean conditions using deionized water. Analytic standards of Pb, Cd, Fe, and Zn were prepared from solutions of metal nitrate (BDH, UK), with concentration of 1000 mg/L. All chemicals used were ultra-pure reagents grade. All glass-ware and plastic-ware were washed 3 times with deionized water then soaked in 20% nitric acid overnight. After soaking, the glass-ware was washed 3 times with deionized water and dried. Quality assurance was achieved by measuring blank test solutions. All metal contents were measured in duplicate (standard deviation [SD] <10%) by the working curve method.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15 (IBM Corporation, USA). Qualitative data were presented as number and percent. Quantitative data were presented as mean ± SD and (min–max). Student's t-test was used to compare between two groups. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

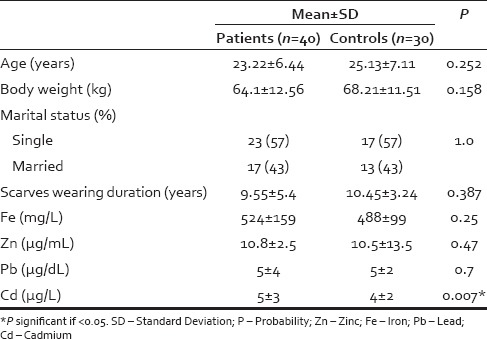

Table 1 shows age, body weight, marital status, and scarves wearing duration of patient and control groups. All participants were wearing scarves. Hair fall was of insidious onset and progressive course and was not preceded by mental stress. The duration of hair fall ranged from 6 months to 9 years (1.59 ± 1.47 years). All the patients documented taking good dieting.

Table 1.

Age, body weight, marital status, scarves wearing duration, and Fe, Zn, Pb, and Cd total blood levels in patient and control groups

Fe, Zn, Pb, and Cd total blood levels of patient and control groups are presented in Table 1. Cd total blood level showed significant positive correlation with the patient's body weight (r = 0.351 and P = 0.026). There were no statistically significant correlations between levels of Cd, Pb, Zn, and Fe in patients group.

DISCUSSION

Hair loss is a common and stressful problem that provokes anxieties more intense than its objective severity seems. The burden of hair loss for some patients may be comparable to more severe chronic or life-threatening diseases.[26] A reasonable number of females were found to have CTE where a specific trigger cannot be identified.[5] It was suggested that CTE might be secondary to a reduction in the duration of anagen.[6] Diagnosis of CTE requires exclusion of other causes of chronic diffuse telogen hair loss with the help of a thorough history, full clinical examination, and investigations.[27]

Exposure to toxic metals has become an increasingly recognized source of illness worldwide. Pb is one of the most hazardous and cumulative pollutants.[28] Cd also is considered as one of the most toxic substances in the environment due to its wide range of organ toxicity and long elimination half-life of 10–30 years.[29] The most important nonoccupational sources of exposure are food (especially seafood from metal-polluted area), drinking water (mostly from Pb pipes in contact with soft and acidic water), air (especially Pb from gasoline in dense traffic areas), Pb-based paints of housing, and smoking (Cd and to lesser extent Pb from tobacco).[19]

The present study included 40 female patients fulfilling the criteria of CTH, but the course of the condition was progressive rather than fluctuating. Total blood Fe levels in patients and controls were within normal range reported in females (400–600 mg/L).[30] This is in agreement with several studies that found no direct relationship between Fe levels and hair loss in females with CTE.[11,12,13,14]

Also, total blood Zn levels of patients and controls were within the average normal range as detected in whole blood of healthy females (5.852 ± 1.229 µg/mL).[31] Consistent with this result, there are studies found that there was no evidence to support low serum Zn concentrations in the CTE.[9,17,32] Also, Harrison and Sinclair[5] suggested that TE alone with no other symptoms or signs of decreased Zn levels is never due to dietary Zn deficiency.

Total Pb blood levels, also, in patients and controls were less than the acceptable blood concentrations in healthy persons without excessive exposure to environmental sources of Pb (<5 µg/dL for children and <10 μg/dL in adults).[33] Furthermore, Pb levels were below the reference range for healthy individuals living in Mansoura City, Dakahlia Governorate (12.43 ± 3.77 µg/dL).[34]

However, Pb blood level is not a good indicator of health as it can frequently be normal in spite of chronic toxicity. Pb is deposited primarily in the bones and the brain so that only minimal levels remain in the blood about 30 days after exposure.[35] Rossi[36] found an elevated risk of peripheral arterial disease, hypertension and renal dysfunction in persons with Pb blood levels about 2 μg/dL. Moreover, Menke et al.[37] reported that level <10 μg/dL is not considered safe, and an increased possibility of death from heart attack or stroke was seen in people with blood levels >2 μg/dL.

In the current study, the total blood Cd level was significantly higher in patients (5 ± 3 µg/L) than controls (4 ± 2 µg/L) and both were higher than that reported by Cerna et al.[38] and Nordberg[39] in whole blood of healthy nonsmokers (0.4–1 µg/L), and than that estimated in healthy nonsmokers living in Mansoura City, Dakahlia Governorate (1.37 ± 0.45 µg/L).[34] Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers a whole blood Cd level ≥ 5 µg/L hazardous.[40]

High Cd blood levels may be due to variable environmental sources of exposure with the absence of general preventive policies. Human exposure to Cd happens mainly through inhalation or ingestion. Cigarette smoking is considered as the most significant source of human Cd exposure. Intestinal absorption is greater in persons with Fe, calcium, or Zn deficiency.[41] Satarug and Moore[42] found a three- to four-fold increase in Cd body burden among Thai women who had low Fe stores, and Kippler et al.[43] found increased Cd burden among Bangladeshi women associated with low Fe stores.

Many studies showed increased Cd and Pb levels in Egyptian environment. Salama and Radwan[20] found that Cd and Pb contents in some foodstuffs from the Egyptian market were above the acceptable levels as established by the regulatory organizations. They suggested that atmospheric deposition from urban and agricultural areas might Pb to enrichment of these products from Cd and/or Pb. Cd contaminated topsoil is considered as the most likely mechanism for the greatest human exposure through uptake into edible plant.

In another study by Mandour and Azab,[21] Cd and Pb concentrations in surface drinking water samples from Dakahlia Governorate in Egypt were higher than the permissible limits of Egyptian Ministry of Health and WHO. Cd is found in surface water as a pollutant from industries working in the region such as electroplating steel, plastics, and batteries. In addition, Salem et al.[44] suggested that Cd might enter drinking water as a result of corrosion of galvanized pipe.

Furthermore, water, sediments, and fish organs from Lake Manzala in Dakahlia Governorate showed high concentrations of Cd and Pb than those from other lakes. Fish may pose health hazards for consumers. In Egyptian irrigation system, the main source of Pb is industrial wastes while that of Cd is the phosphatic fertilizers used in crop farms and sewage sludge disposal.[22]

In the present study, it is suggested that elevated Cd blood level in the presence of Pb may be the hidden cause of the idiopathic hair fall. Toxic effects of Cd are magnified by interaction with other toxic metals such as Pb as co-exposure to Pb and Cd has synergistic cytotoxicity.[45] Cd and Pb can induce hair loss by many possible mechanisms. This is supported by Pierard[46] who reported toxic metals ingestion in 36 of 78 patients with diffuse hair loss with Cd identification in two cases. Metal ions were not increased in the hair shaft of patients, presenting a toxic alopecia, suggesting that they exerted their effect in promoting a premature end of the hair cycle rather than a progressive metabolic alteration of the process of keratinization so far. In addition, Trüeb[18] reported that many heavy metals (thallium, mercury, arsenic, copper, Cd, and bismuth) were capable of disrupting the formation of hair shaft through covalent banding with the sulfhydryl groups in keratin.

Moreover, hair loss associating Cd and/or Pb toxicity may be due to relative Zn deficiency.[19] Binding to metallothionein is necessary for utilization of Zn. Cd and Pb compete with Zn and bind more tightly to metallothionein thus, alteration in the amount and/or biological availability of Zn occurs.[47] As a cofactor of metalloenzyme, Zn is involved in hair follicle cycling and hair growth.[48] Zn is essential for more than 300 enzymes, important for nucleic acid and protein synthesis and cell division.[49] Also, there is aberrant Zn-dependent immunological control of hair growth.[50] Furthermore, Zn is a catagen inhibitor via its inhibitory action on apoptosis-related endonucleases.[51] Finally, Zn is a component of Zn finger motifs for many transcription factors that control hair growth through hedgehog signaling.[52]

In addition to Zn, a number of important Fe-dependent metabolic steps can be inhibited by Pb and Cd.[19] Iron (Fe) is needed for Fe-dependent coenzymes such as stearyl-coenzyme A desaturase and as a cofactor for ribonucleotide reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme for DNA synthesis.[53] In addition, hair follicle matrix cells are among the most rapidly dividing cells in the body and they have lower levels of ferritin and higher levels of free Fe and may be finely sensitive even to a minor decrease in Fe availability.[54]

Generation of reactive oxygen species caused by Pb and Cd exposure may result in oxidative damage to critical biomolecules.[55] Hair exposed to oxidative stress may show potential damage as repeated oxidative stress or inhibition of mitochondrial function may Pb to apoptosis and hair loss.[56,57] Also, Pb and Cd make alterations in the antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, glutathione-S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, and of nonenzymatic molecule like glutathione that normally protect against free radical toxicity.[55] Depletion of glutathione has been observed, as structural alteration of proteins due to Cd binding to sulfhydryl groups.[58] Furthermore, Cd induces tissue injury through increased lipid peroxidation,[55] epigenetic changes in DNA expression,[59] and inhibition or upregulation of transport pathways.[60]

Effective antioxidant therapies are suggested and there are evidences that selenium,[61] Zn,[62] carotenoids and Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E[55] and factors increasing levels of Nuclear factor-erythroid 2–related factor 2 (that induces cytoprotective and antioxidant enzymes)[63] may partially antagonize the toxic effects of Cd and Pb. Antioxidant food supplements are found in various forms: Vegetables, fruits, grain cereals, legumes, and nuts.[64] Also, Zn is very protective against Cd and Pb absorption in the intestines. Zn can enhance interstitial cells efflux of Cd. Also, Zn and Pb compete for similar binding sites on the metallothionein like transport protein in the gastrointestinal tract, and this competition decreases Pb absorption.[55]

CONCLUSION

Estimation of total blood Pb and Cd levels may be important in cases of unexplained hair fall. Reduction of increased heavy metal body load by preventive measures and drugs is mandatory. Cases with hair fall should be advised to optimize caloric, Fe, Zn, and calcium intake specifically to reduce Pb and Cd absorption. Supplementation of antioxidant may reduce hair damage. As rich sources of antioxidants, diet with lots of fruits and vegetable is recommended.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mirmirani P. Managing hair loss in midlife women. Maturitas. 2013;74:119–22. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadshiew IM, Foitzik K, Arck PC, Paus R. Burden of hair loss: Stress and the underestimated psychosocial impact of telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:455–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover C, Khurana A. Telogen effluvium. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:591–603. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.116731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paus R, Olsen EA, Messenger AG. Hair growth disorders. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2008. pp. 753–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison S, Sinclair R. Telogen effluvium. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:389–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilmore S, Sinclair R. Chronic telogen effluvium is due to a reduction in the variance of anagen duration. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:163–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messenger AG, de Berker DA, Sinclair RD. Disorders of hair. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010. pp. 66.27–66.31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rushton DH, Dover R, Sainsbury AW, Norris MJ, Gilkes JJ, Ramsay ID. Iron deficiency is neglected in women's health. BMJ. 2002;325:1176. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7373.1176/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rushton DH. Nutritional factors and hair loss. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:396–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohyama M. Management of hair loss diseases. Dermatol Sin. 2010;28:139–45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinclair R. There is no clear association between low serum ferritin and chronic diffuse telogen hair loss. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:982–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen EA. Iron deficiency and hair loss: The jury is still out. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:903–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bregy A, Trueb RM. No association between serum ferritin levels>10 microg/l and hair loss activity in women. Dermatology. 2008;217:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000118505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen EA, Reed KB, Cacchio PB, Caudill L. Iron deficiency in female pattern hair loss, chronic telogen effluvium, and control groups. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:991–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karashima T, Tsuruta D, Hamada T, Ono F, Ishii N, Abe T, et al. Oral zinc therapy for zinc deficiency-related telogen effluvium. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:210–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2012.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kil MS, Kim CW, Kim SS. Analysis of serum zinc and copper concentrations in hair loss. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:405–9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnaud J, Beani JC, Favier AE, Amblard P. Zinc status in patients with telogen defluvium. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:248–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555752478249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trüeb RM. Systematic approach to hair loss in women. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:284–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telisman S, Jurasovic J, Pizent A, Cvitkovic P. Blood pressure in relation to biomarkers of lead, cadmium, copper, zinc, and selenium in men without occupational exposure to metals. Environ Res. 2001;87:57–68. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salama AR, Radwan MA. Heavy metals (Cd, Pb) and trace elements (Cu, Zn) contents in some foodstuffs from the Egyptian market. Emir J Agric Sci. 2005;17:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandour RA, Azab YA. The prospective toxic effects of some heavy metals overload in surface drinking water of Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2011;2:245–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeed SM, Shaker IM. Assessment of Heavy Metals Pollution in Water and Sediments and their Effect on Oreochromis Niloticus in the Northern Delta Lakes, Egypt. Central Lab for Aquaculture Research, Agricultural Research Center. Limnology Dept. 8th International Symposium on Tilapia in Aquaculture. 2008:475–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piérard GE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Marks R, Elsner P. EEMCO group (European Expert Group on Efficacy Measurement of Cosmetics and other Topical Products). EEMCO guidance for the assessment of hair shedding and alopecia. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17:98–110. doi: 10.1159/000076020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanloon J. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1985. Selected Methods of Trace Metal Analysis: Biological and Environmental Samples; pp. 211–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockwell PB, Corns WT. The role of atomic fluorescence spectrometry in the automatic environmental monitoring of trace element analysis. J Automat Chem. 1993;15:79–84. doi: 10.1155/S1463924693000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cash TF. The psychology of hair loss and its implications for patient care. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:161–6. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair R. Diffuse hair loss. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38 Suppl 1:8–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milnes MR, Bermudez DS, Bryan TA, Edwards TM, Gunderson MP, Larkin IL, et al. Contaminant-induced feminization and demasculinization of nonmammalian vertebrate males in aquatic environments. Environ Res. 2006;100:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Third National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajurkar NS, Patil SF, Zatakia NH. Assessment of iron and haemoglobin status in working women of various age groups. J Chem Pharm Res. 2012;4:2300–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buxaderas SC, Farré-Rovira R. Whole blood and serum zinc levels in relation to sex and age. Rev Esp Fisiol. 1985;41:463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yacoub S, Youssef N, El-Bahrawy M, Elwan AS. Role of Zinc in Telogen Effluvium. Dissertation, Ain Shams University. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosnett MJ, Wedeen RP, Rothenberg SJ, Hipkins KL, Materna BL, Schwartz BS, et al. Recommendations for medical management of adult lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:463–71. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortada WI, Sobh MA, El-Defrawy MM, Farahat SE. Reference intervals of cadmium, lead, and mercury in blood, urine, hair, and nails among residents in Mansoura City, Nile Delta, Egypt. Environ Res Sec A. 2002;90:104–10. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pichery C, Bellanger M, Zmirou-Navier D, Glorennec P, Hartemann P, Grandjean P. Childhood lead exposure in France: Benefit estimation and partial cost-benefit analysis of lead hazard control. Environ Health. 2011;10:44. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi E. Low level environmental lead exposure – A continuing challenge. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menke A, Muntner P, Batuman V, Silbergeld EK, Guallar E. Blood lead below 0.48 micromol/L (10 microg/dL) and mortality among US adults. Circulation. 2006;114:1388–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerná M, Spevácková V, Benes B, Cejchanová M, Smíd J. Reference values for lead and cadmium in blood of Czech population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2001;14:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordberg GF. Biomarkers of exposure, effects and susceptibility in humans and their application in studies of interactions among metals in China. Toxicol Lett. 2010;192:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.06.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Sep, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). ToxFAQs: Cadmium. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordberg GF, Nogawa KM, Nordberg M, Friberg L. Cadmium. In: Nordberg GF, Fowler BF, Nordberg M, Friberg L, editors. Handbook of the Toxicology of Metals. 3rd rd. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 445–86. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satarug S, Moore MR. Adverse health effects of chronic exposure to low-level cadmium in foodstuffs and cigarette smoke. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1099–103. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kippler M, Ekström EC, Lönnerdal B, Goessler W, Akesson A, El Arifeen S, et al. Influence of iron and zinc status on cadmium accumulation in Bangladeshi women. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222:221–6. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salem HM, Eweida EA, Farag A. ICEHM: International Conference for Environmental Hazard Mitigation, Cairo University, Egypt, September, 2000. Cairo University; 2000. Heavy metals in drinking water and their environmental impact on human health; pp. 542–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whittaker MH, Wang G, Chen XQ, Lipsky M, Smith D, Gwiazda R, et al. Exposure to Pb, Cd, and as mixtures potentiates the production of oxidative stress precursors: 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day drinking water studies in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;254:154–66. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierard GE. Toxic effects of metals from the environment on hair growth and structure. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moulis JM. Cellular mechanisms of cadmium toxicity related to the homeostasis of essential metals. Biometals. 2010;23:877–96. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plonka PM, Handjiski B, Popik M, Michalczyk D, Paus R. Zinc as an ambivalent but potent modulator of murine hair growth in vivo- preliminary observations. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:844–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanagisawa H. Zinc deficiency and clinical practice–validity of zinc preparations. Pharm Soc Jpn. 2008;128:333–9. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paus R, Christoph T, Müller-Röver S. Immunology of the hair follicle: A short journey into terra incognita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:226–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marini M, Musiani D. Micromolar zinc affects endonucleolytic activity in hydrogen peroxide-mediated apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 1998;239:393–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli proteins and Hedgehog signaling: Development and cancer. Trends Genet. 1999;15:418–25. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kantor J, Kessler LJ, Brooks DG, Cotsarelis G. Decreased serum ferritin is associated with alopecia in women. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:985–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trost LB, Bergfeld WF, Calogeras E. The diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency and its potential relationship to hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:824–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patra RC, Rautray AK, Swarup D. Oxidative stress in lead and cadmium toxicity and its amelioration. Vet Med Int. 2011;2011:457327. doi: 10.4061/2011/457327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trüeb RM. Oxidative stress in ageing of hair. Int J Trichology. 2009;1:6–14. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.51923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker K, Staecker H. Low dose oxidative stress induces mitochondrial damage in hair cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295:1868–76. doi: 10.1002/ar.22594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valko M, Morris H, Cronin MT. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1161–208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang B, Li Y, Shao C, Tan Y, Cai L. Cadmium and its epigenetic effects. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:2611–20. doi: 10.2174/092986712800492913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wan L, Zhang H. Cadmium toxicity: Effects on cytoskeleton, vesicular trafficking and cell wall construction. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:345–8. doi: 10.4161/psb.18992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zwolak I, Zaporowska H. Selenium interactions and toxicity: A review. Selenium interactions and toxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2012;28:31–46. doi: 10.1007/s10565-011-9203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volpe AR, Cesare P, Aimola P, Boscolo M, Valle G, Carmignani M. Zinc opposes genotoxicity of cadmium and vanadium but not of lead. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2011;25:589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu KC, Liu JJ, Klaassen CD. Nrf2 activation prevents cadmium-induced acute liver injury. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;263:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernhoft RA. Cadmium toxicity and treatment. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:394652. doi: 10.1155/2013/394652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]