Abstract

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) and fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution (FAPD) represent clinically distinctive conditions characterized by pattern hair loss with evidence of follicular inflammation and fibrosis. Since Kossard's original description, the condition has been recognized to represent a rather generalized than localized process, with extension well beyond the frontotemporal hairline. More recently, peculiar facial papules have been reported in FFA representing facial vellus hair involvement. We report the case of a 42-year-old woman with FAPD associated with the same facial papules, supporting that both entities belong to the same spectrum of cicatricial pattern hair loss.

Keywords: Facial papules, frontal fibrosing alopecia, fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution, cicatricial pattern hair loss

INTRODUCTION

Since Kossard's original description of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) in 1994 as a scarring alopecia characterized by progressive recession of the frontotemporal hairline in postmenopausal women,[1] Zinkernagel and Trüeb reported in 2000 yet another form of fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution (FAPD) affecting the centroparietal area of the scalp, histologically with a lichenoid type of follicular inflammation and fibrosis.[2] Ultimately, in 2005 Olsen acknowledged the existence of clinically significant inflammatory phenomena and fibrosis in pattern hair loss and proposed the term “cicatricial pattern hair loss.”[3] Finally, FFA has been recognized to represent a rather generalized than localized process of inflammatory scarring alopecia,[4] with extension beyond the frontotemporal hairline, loss of eyebrows and of eyelashes, loss of peripheral body hair,[5] mucous membrane,[6] and nail involvement.[7] More recently, peculiar facial papules have been reported in association with FFA representing facial vellus hair involvement and described by patients as “roughening” of facial skin.[8] We report a case of facial papules in a woman with FAPD, further supporting that both entities belong to the same spectrum of pattern hair loss with evidence of follicular inflammation and fibrosis (cicatricial pattern hair loss).

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old female patient presented with a 20-year history of hair loss for which she had been treated with topical 2% minoxidil solution twice daily.

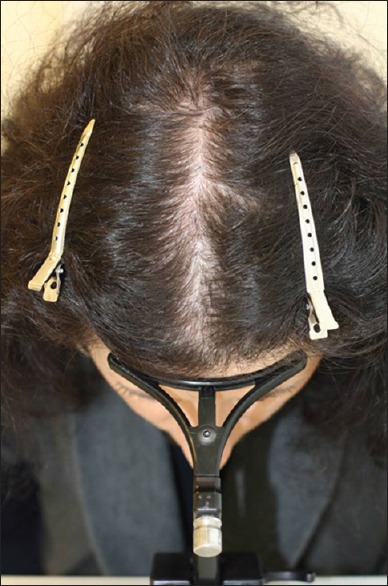

Clinical examination showed hair thinning of the crown area with a widened hair part with irregular borders and small clear areas of decreased density on both sides of the part line [Figure 1]. There was associated lateral rarefaction of eyebrows [Figure 2]. The frontal hairline was intact.

Figure 1.

Hair thinning of the crown area with a widened hair part with irregular borders and small clear areas of decreased density on both sides of the part line

Figure 2.

Associated lateral rarefaction of eyebrows

Dermoscopic examination revealed diversity of hair shaft diameters associated with evidence of follicular inflammation and fibrosis: Perifollicular scaling and confluent white areas on a milky red background [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Diversity of hair shaft diameters associated with evidence of follicular inflammation and fibrosis: Perifollicular scaling and confluent white areas on a milky red background

Laboratory evaluation for comorbidites and autoimmunity (CRP, ferritin, basal TSH, vitamin B12, vitamin D3, ANA, and prolactin, resp. anti-SSA (Ro), anti-SSB (La), anti-Sm, anti nRNP (ribnonuclein), anti-histone, anti-Jo-1, anti-PM-Scl (p57/100) and a CBC revealed an elevated ANA titer (1:1’280) and elevated anti-SSA-60/52 ((Ro) (46 U)), without further clinical or laboratory evidence for systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren's syndrome.

A diagnosis of FAPD with serologic evidence for autoimmunity was made. The patient was successfully treated with oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid for the first 4 weeks, thereafter 200 mg daily, topical 0.05% clobetasol propionate, and 5% topical minoxidil solution that was later replaced with a compound of 5% topical minoxidil 0.2% triamcinolone acetonide solution [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

After 12 weeks of successful treatment with oral hydroxychloroquine and topical corticosteroids in combination with topical minoxidil

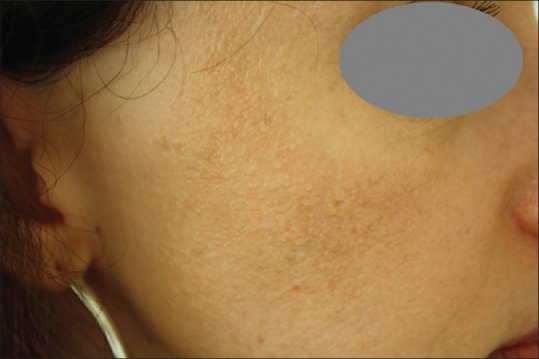

Incidentally, the patient complained of as “ roughening of facial skin.” Clinical examination revealed skin colored facial papules of the malar and temporal regions [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Skin colored facial papules of the malar and temporal regions

DISCUSSION

Frontal fibrosing alopecia represents a distinctive condition originally described by Kossard in postmenopausal women presenting with a symmetric, marginal alopecia along the frontal and frontal-temporal hairline, with concomitant thinning or complete loss of the eyebrows in 50–70% of cases.[1] On the basis of histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies, Kossard eventually interpreted this type of alopecia as a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP),[9] and suggested that the condition may hold the key to understand the complex relationship of pattern alopecia, sex-related differences, and triggers for autoimmune follicular destruction.[10] Finally, the observation of cutaneous lupus erythematosus mimicking FFA suggests that the pattern of clinical disease presentation might be more specific for the condition than the underlying inflammatory autoimmune reaction.[11,12,13]

In Zinkernagel and Trüeb's original description of FAPD,[2] patients display progressive scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Close clinical examination reveals obliteration of follicular orifices, perifollicular erythema, and follicular keratosis limited to the area of androgenetic hair loss. Histological evidence of androgenetic alopecia, i.e. increased numbers of miniaturized hair follicles with underlying fibrous streamers, is associated with a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions are characterized by a pattern of follicular interface dermatitis targeting the upper follicle, whereas late lesions show perifollicular lamellar fibrosis and the presence of selectively fibrosed follicular tracts.

Since Kossard's original description, the number of cases of FFA has not only exploded exponentially worldwide to include premenopausal women and men, but it seems that considerable overlap exists among FFA, LPP, and FAPD: FFA has been described in association with lichen planus elsewhere (oral cavity,[6] nails[7]), and FFA–type changes may be observed in patients with FAPD or LPP (personal observation).

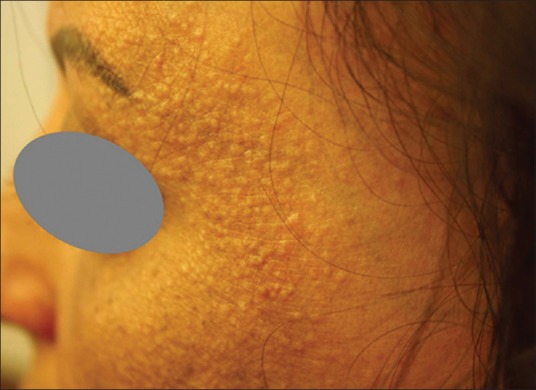

Most recently, peculiar facial papules have been reported in association with FFA representing facial vellus hair involvement [Figure 6]. The clinical picture involves follicular micropapules randomly distributed over the facial skin but readily more visible over the temporal regions. No desquamation or erythema is present, and facial vellus are decreased or absent. Inframandibular or retroauricular areas may also be affected. Histologic examination of these lesions showed LLP features similar to scalp FFA.[8]

Figure 6.

Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia

We observed the same type of peculiar facial papules [Figure 5] originally described in FFA in a woman with FAPD and serologic evidence for autoimmunity (elevated ANA titer and anti-SSA-60/52 [Ro]), but without further clinical or laboratory evidence for systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren's syndrome.

While the etiology of FFA and FAPD has remained obscure, the observation of facial papules in both conditions provides further evidence that both entities may belong to the same spectrum of pattern hair loss with evidence of a lichenoid pattern of follicular inflammation and fibrosis (cicatricial pattern hair loss). Moreover, both may be associated with serologic or clinical evidence of autoimmunity, specifically autoimmune thyroid disease or lupus erythematosus.

The lichenoid pattern of inflammation is understood to represent a T-cell mediated autoimmune reaction with an unknown initial trigger with striking analogies to cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. This autoimmune process triggers apoptosis of epithelial cells. In cicatricial pattern hair loss, it has been proposed that follicles with some form of damage or malfunction might express cytokine profiles that attract inflammatory cells to assist in damage repair or in the initiation of apoptosis mediated organ deletion. Alternatively, an as yet unknown antigenic stimulus from the damaged or malfunctioning hair follicle might initiate a lichenoid tissue reaction in the immunogenetically susceptible individual.[2]

There is no cure for LPP, FFA or FAPD, but a number of treatments have been proposed to control symptoms or halt disease progression.[14,15,16,17,18] Topical minoxidil and oral dutasteride are indicated where androgenetic alopecia represents a co-morbid condition, while topical and/or systemic anti-inflammatory treatment modalities target the inflammatory component (topical or intralesional corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and oral doxycycline, hydroxychloroquine or mycophenolate mofetil), with the potential of improvement of the facial skin surface.[8]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

This case report represents an integral part of Ausrine Ramanauskaite's traineeship in trichology at the Center for Dermatology and Hair Diseases Professor Trüeb.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinkernagel MS, Trüeb RM. Fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution: Patterned lichen planopilaris or androgenetic alopecia with a lichenoid tissue reaction pattern? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:205–11. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen EA. Female pattern hair loss and its relationship to permanent/cicatricial alopecia: A new perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:217–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew AL, Bashir SJ, Wain EM, Fenton DA, Stefanato CM. Expanding the spectrum of frontal fibrosing alopecia: A unifying concept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:653–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armenores P, Shirato K, Reid C, Sidhu S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia associated with generalized hair loss. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:183–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tr:1 RM, Toricelli R. Lichen planopilaris unter dem Bild einer postmenopausalen frontalen fibrosierenden Alopezie (Kossard) Hautarzt. 1998;49:388–91. doi: 10.1007/s001050050760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macpherson M, Hohendorf-Ansari P, Trüeb RM. Nail involvement in frontal fibrosing Alopecia. Int J Trichology. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.160107. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, Valente NS, Romiti R. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: Evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: A frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kossard S. Post-menopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. In: Trope RM, Tobin DJ, editors. Aging Hair. Heidelberg and Berlin: Soringer; 2010. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaffney DC, Sinclair RD, Yong-Gee S. Discoid lupus alopecia complicated by frontal fibrosing alopecia on a background of androgenetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:217–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan S, Fenton DA, Stefanato CM. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lupus overlap in a man: Guilt by association? Int J Trichology. 2013;5:217–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Rei M, Pirmez R, Sodré CT, Tosti A. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia and discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp in 7 patients: Just a coincidence? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jdv.12642. doi: 101111/jdv12642. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoulis A, Georgala S, Bozi E, Papadavid E, Kalogeromitros D, Stavrianeas N. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Treatment with oral dutasteride and topical pimecrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:580–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgala S, Katoulis AC, Befon A, Danopoulou I, Georgala C. Treatment of postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia with oral dutasteride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:157–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Selim MA, Olsen EA. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banka N, Mubki T, Bunagan MJ, McElwee K, Shapiro J. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective clinical review of 62 patients with treatment outcome and long-term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1324–30. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, Arias-Santiago S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Garnacho-Saucedo G, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]