Abstract

Autosomal recessive mutations in proteasome subunit β 8 (PSMB8), which encodes the inducible proteasome subunit β5i, cause the immune-dysregulatory disease chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE), which is classified as a proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (PRAAS). Here, we identified 8 mutations in 4 proteasome genes, PSMA3 (encodes α7), PSMB4 (encodes β7), PSMB9 (encodes β1i), and proteasome maturation protein (POMP), that have not been previously associated with disease and 1 mutation in PSMB8 that has not been previously reported. One patient was compound heterozygous for PSMB4 mutations, 6 patients from 4 families were heterozygous for a missense mutation in 1 inducible proteasome subunit and a mutation in a constitutive proteasome subunit, and 1 patient was heterozygous for a POMP mutation, thus establishing a digenic and autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of PRAAS. Function evaluation revealed that these mutations variably affect transcription, protein expression, protein folding, proteasome assembly, and, ultimately, proteasome activity. Moreover, defects in proteasome formation and function were recapitulated by siRNA-mediated knockdown of the respective subunits in primary fibroblasts from healthy individuals. Patient-isolated hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells exhibited a strong IFN gene-expression signature, irrespective of genotype. Additionally, chemical proteasome inhibition or progressive depletion of proteasome subunit gene transcription with siRNA induced transcription of type I IFN genes in healthy control cells. Our results provide further insight into CANDLE genetics and link global proteasome dysfunction to increased type I IFN production.

Introduction

Monogenic autoinflammatory diseases are immune-dysregulatory conditions that often present in the perinatal period with sterile episodes of fever and excessive organ-specific inflammation (1); genetic defects in innate immune pathways can cause intracellular stress, leading to cytokine dysregulation (2). Autosomal recessive homozygous or compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in proteasome subunit β 8 (PSMB8), which encodes the inducible proteasome component β5i, cause a syndrome that has historically been referred to as joint contractures, muscle atrophy, microcytic anemia, and panniculitis-induced childhood-onset lipodystrophy (JMP) syndrome, Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome (NNS), or chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE). These conditions form 1 disease spectrum of proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (PRAAS) (3–6). Characteristic clinical features include early presentation with fever, nodular skin rashes, myositis, panniculitis-induced lipodystrophy, and basal ganglion calcifications. In contrast to what occurs in many currently known autoinflammatory diseases, patients with CANDLE/PRAAS do not respond to IL-1 inhibition. The expression of a strong IFN-response gene signature suggests a possible association of proteasome dysfunction and IFN dysregulation, but the type of IFN driving the signature has not been well defined (6).

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) degrades intracellular proteins derived from self or foreign structures and has a major role in the removal of misfolded proteins (7). The 20S core of the proteasome comprises 2 outer α-rings and 2 inner β-rings in an α1–7β1–7β1–7α1–7 configuration. It contains 3 proteolytically active sites, 1 located in the β1 subunit conferring caspase-like activity, 1 in the β2 subunit conferring trypsin-like activity, and 1 in the β5 subunit conferring chymotrypsin-like activity. The 20S-core complex can be capped with 19S regulatory units, which recognize ubiquitin-protein conjugates, or with the PA28 regulator (8), forming 26S proteasomes or hybrid proteasomes, respectively (9).

Thus far, CANDLE/PRAAS-causing mutations have only been reported in PSMB8, which encodes an alternative inducible catalytic proteasome subunit designated as β5i (also known as LMP7) (4–6, 10, 11). There are 2 other inducible active sites, β1i (also known as LMP2 and encoded by PSMB9) and β2i (also known as Mecl1 and encoded by PSMB10), which can be incorporated into nascent proteasome complexes to form immunoproteasomes and thus increase proteolytic capacity. In most tissues, immunoproteasome formation is induced by proinflammatory cytokines, but it is constitutively expressed in hematopoietic cells (12, 13).

Helper proteins govern the assembly and maturation of either standard or immunoproteasomes; one such protein, proteasome maturation protein (POMP), is essential for proteasome formation and cell viability and preferentially supports incorporation of the inducible β5i subunit. Most proteasomal β subunits, except for β3 and β4, are synthesized as proforms that are matured through autocatalytic cleavage during the assembly process, which liberates the active-site threonines (14, 15). Most proteasomal β subunits, except for β3 and β4, are synthesized as proforms that are matured through autocatalytic cleavage during the assembly process, which liberates the active-site threonines.

As β5i-deficient mice do not exhibit a spontaneous inflammatory or metabolic phenotype, the presence of inflammatory disease manifestations in patients with PSMB8 mutations is surprising and raises questions about disease-causing mechanisms. Mouse models link immunoproteasome dysfunction to oxidative stress, accumulation of toxic ubiquitin-rich aggregates, and cytokine dysregulation, suggesting a role for immunoproteasomes in tissue preservation during inflammatory processes (16, 17).

Here, we demonstrate that CANDLE/PRAAS can be caused by either monogenic or digenic inheritance of hypomorphic or loss-of-function mutations in immunoproteasome and in constitutive proteasome subunits. Our data suggest that global proteasome dysfunction irrespective of genotype and the specific proteolytic subunit affected is linked to the upregulation of type I but not type II IFN production. Thus, our data suggest that proteasome dysfunction can lead to chronic type I IFN induction, establishing CANDLE as an IFN-mediated autoinflammatory disease.

Results

Identification of novel mutations in constitutive and inducible proteasome genes suggests digenic inheritance.

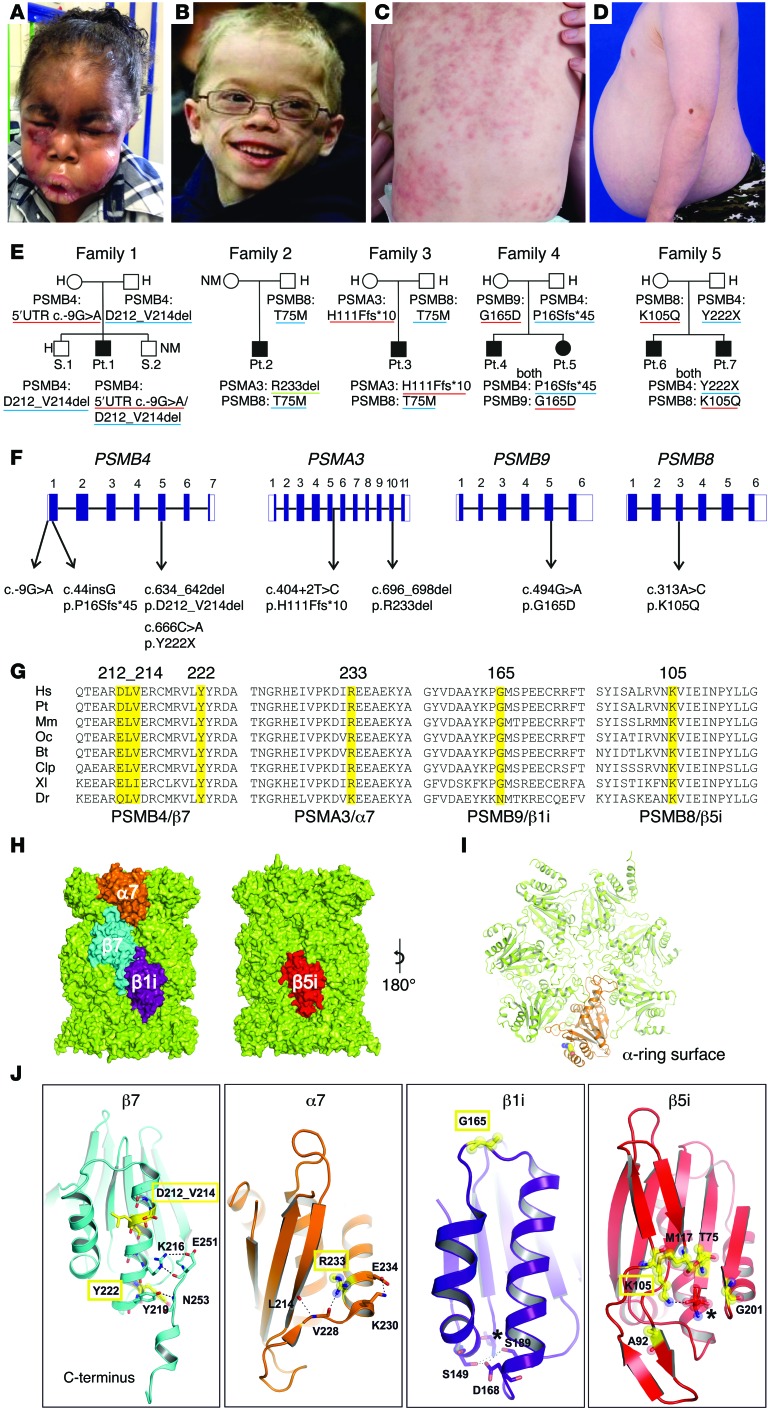

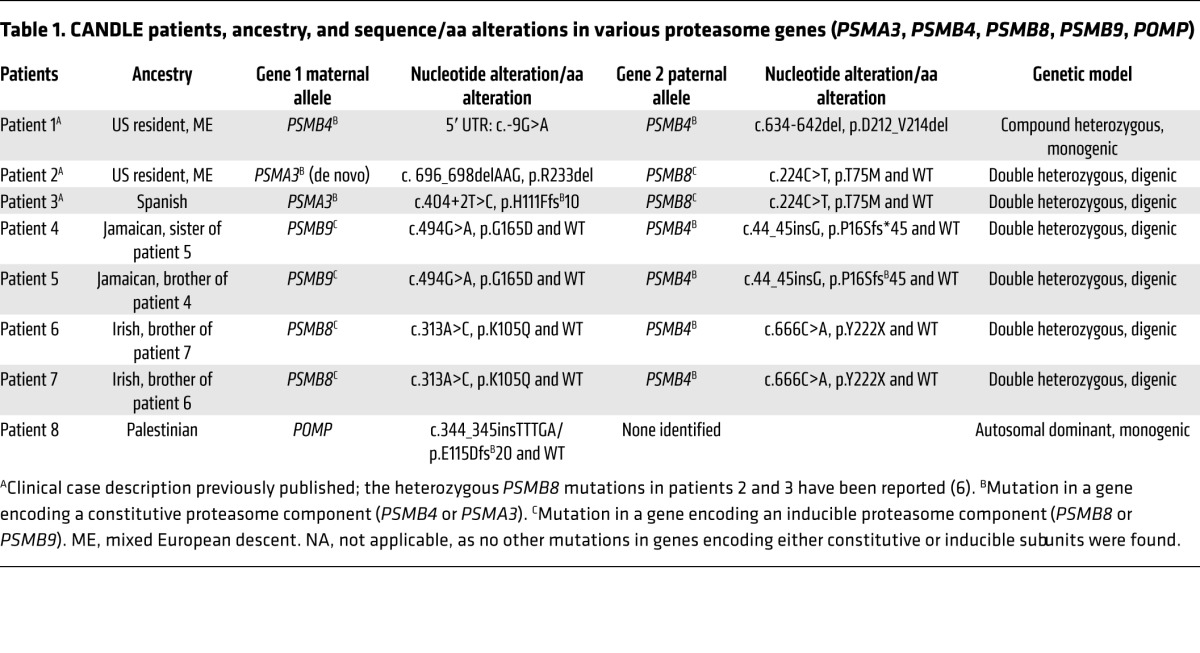

We studied 8 patients (patients 1-8) with the clinical phenotype of CANDLE (Figure 1, A–D, Table 1, and Supplemental Figure 1, A–D; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI81260DS1) who had no known PSMB8 mutation (patients 1, 4, 5, and 8) or were heterozygous for only 1 disease-associated mutation in the PSMB8 gene: p.T75M (patients 2 and 3) or p.K105Q (patients 6 and 7). Clinical and demographic features are presented in Supplemental Table 1. We hypothesized that additional proteasome genes may cause CANDLE and screened 14 proteasome candidate genes encoding the proteasome subunits and the proteasome assembly gene, POMP, by standard sequencing (patients 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). Three patients (patients 1, 2, 8) and the unaffected parents of patient 2 were evaluated by whole-exome sequencing (WES) to facilitate screening and to rule out additional shared variants that may contribute to disease.

Figure 1. Clinical findings and CANDLE/PRAAS-associated mutations in 4 proteasome-encoding genes and in silico modeling.

(A) Marked facial edema during flare. (B) Lipoatrophy later in life. (C) CANDLE rash during acute flare. (D) Abdominal protrusion due to intraabdominal fat deposition. (E) Pedigrees and identified genotypes of patients and their direct relatives. Underline in red indicates maternal, in blue, paternal, and in green, de novo inheritance of mutant allele. (F) Schematic organization of PSMB4, PSMA3, PSMB9, and PSMB8 genes (exon-intron structure, black rectangles represent coding sequences, white rectangles represent UTRs) with positions of the identified mutations. (G) Species conservation of mutated aa (yellow). Hs, Homo sapiens; Pt, Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee); Mm, Mus musculus (mouse); Oc, Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit); Bt, Bos tauris (cattle); Clp, Canis lupus familiaris (dog); Xl, Xenopus laevis (frog), Dr, Danio rerio (zebrafish). Alignment was performed with ClustalW. (H) PSMB8 and PSMB9 mutations were modeled based on the x-ray structure of the mouse immunoproteasome (PDB entry code: 3UNH) (46), and the mutations in PSMA3 and PSMB4 were based on the bovine 20S proteasome (PDB entry code: 1IRU) (19). Mutated subunits α7 (orange), β7 (cyan), and β1i (purple) are located at the opposite side of the 20S particle compared with β5i (red). (I) Top view of α ring. Subunit α7 (orange) with mutant residue R233 (balls) highlighted. (J) Detailed perspectives of ribbon models of mutant proteins. Mutated residues are depicted in yellow with relevant interaction aa side chains shown with stick models. Novel mutations are highlighted in yellow rectangles. Catalytic active sites in β1i and β5i are marked with asterisks. H, heterozygous, NM, nonmutant.

Table 1. CANDLE patients, ancestry, and sequence/aa alterations in various proteasome genes (PSMA3, PSMB4, PSMB8, PSMB9, POMP).

Patient 1 was compound heterozygous for 2 PSMB4 mutations encoding the constitutive β7 subunit, a rare 5′ UTR point mutation, c.-9G>A (rs200946642), and a novel 9 bp in-frame deletion (c.634-642del/p.D212_V214del). Both unaffected parents and 1 of 2 unaffected siblings were carriers for one of the respective mutations (Figure 1, E and F, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

Two unrelated patients, patient 2 and patient 3, with a known, paternally inherited PSMB8 mutation (p.T75M) each had a different novel mutation in PSMA3, encoding the constitutive α7 subunit. Patient 2 had a de novo heterozygous 3-bp in-frame deletion in PSMA3 (c. 696_698delAAG/p.R233del), and patient 3 inherited a splice-site mutation in PSMA3 (c.404+2T>G/p.H111Ffs*10) from his unaffected mother (Figure 1, E and F, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

Two affected Jamaican siblings, patients 4 and 5, inherited a novel monoallelic PSMB4 (β7-encoding) variant (c.44insG/p.P16Sfs*45) from their father and a rare missense substitution affecting a highly conserved aa residue, c.494G>A/p.G165D (rs369359789), in the inducible subunit PSMB9 (β1i encoding) from their mother (Figure 1, E and F, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

Two affected Irish siblings, patients 6 and 7, inherited a novel monoallelic nonsense mutation in PSMB4, c.666C>A/p.Y222X, from their father and a novel heterozygous missense mutation in PSMB8, c.313A>C/p.K105Q, from their mother (Figure 1, E and F, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

An adopted patient of Palestinian descent (previously described in ref. 18) had a novel heterozygous frameshift mutation in POMP (c.344_345insTTTGA/p.E115Dfs*20) (Supplemental Figure 2A, Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

For the 8 novel or rare CANDLE-associated mutations in 1 inducible and 3 constitutive proteasome subunit genes and in POMP, the allele frequencies and pathogenicity predictions for the novel mutations are summarized in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3 and in Supplemental Results.

In silico modeling and gene-expression studies suggest effects of mutations on protein-folding proteolytic activity and protein expression levels.

All mutations were predicted to be pathogenic based on their conservation in vertebrates and on structural modeling by using the x-ray structures of bovine (19) and mouse 20S proteasomes (ref. 20 and Figure 1, G–J).

The 3-aa deletion in β7, p.D212-V214 (family 1), was located at the N terminus of an α-helix forming an intramolecular hydrogen-bonding network that stabilized its C-terminal extension. The p.P16Sfs*45 (family 4) and the p.Y222X (family 5) mutations caused the loss of the C-terminal extension of β7 (Figure 1, G–J), which is essential for proteasome assembly (21).

The p.R233del deletion in PSMA3 (family 2) distorted a surface of an α-helix–stabilizing motif of the α7 subunit and likely affected the subunit folding (Figure 1, H and J) and attachment of regulatory complexes (Figure 1I).

The β1i variant, p.G165D (family 4), was located in a loop interconnecting 2 α-helices (Figure 1J) that define the position of a β1i/caspase-like activity conferred by threonine (T1). The PSMB8 mutation p.K105Q (family 5) affected aa positions that directly regulate to β5i/chymotrypsin-like activity (20).

We next assessed allele-specific transcription of various mutant transcripts in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (patients 1–5). In family 1, the maternally inherited mutant PSMB4 allele (c.-9G>A) was expressed at lower levels than the WT allele, both in patient 1 and in his unaffected mother (Figure 2A). The unaffected father who carried the 3-aa deletion in the same gene may have had increased expression of PSMB4 transcripts, indicating transcriptional compensation.

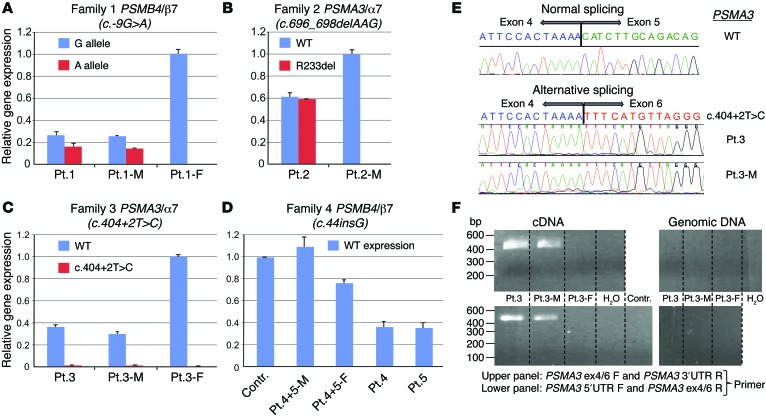

Figure 2. Analysis of mutated gene expression.

(A) Using WT and mutant allele (5′UTR: c.-9G>A) specific primers to assess PSMB4 expression, the mutant transcript shows significantly lower expression than WT transcript. This is observed in patient 1 and his mother (Pt.1-M) when comparing WT (blue bar in Pt.1-M) and maternal PSMB4 mutant (red) transcript level. Patient 1 and his father (Pt.1-F) carry the PSMB4 (β7) 3-aa deletion detected as the G allele here; in the patient, the G allele is the amplified mutant paternal allele; in the father the expression level includes WT and the 3-aa deletion allele. (B) WT and mutant (c.696_698del, p.R233del) PSMA3 allele from patient 2 shows equal transcription for both. (C) PSMA3 c.404+2T>C mutation on splicing of exon 5 leads to unstable transcription of the mutant allele. (D) Reduced expression of PSMB4 is seen in the asymptomatic father (Pt.4+5-F) and in patient 4 and patient 5 who are heterozygous for the c.44_45insG mutation allele. The father may compensate with increased transcription of the WT allele. The mother (Pt.4+5-M) has 2 WT alleles for PSMB4 (she carries the p>G165D mutation in PSMB9). Contr., healthy adult control. (A–D) Tests were conducted as technical triplicates. (E) Sequencing of the PCR amplified product shows skipping of exon 5. (F) Mutant transcript lacking exon 5 is amplified with the junction-specific primers (patient 3 and his mother [patient 3-M], both carry the c.404+2T>C [p.H111Ffs*10] mutation). The amplification of mutant transcript from cDNA was performed using 2 different junction-specific exon 4/6 spanning primer sets that failed to amplify genomic DNA, as expected. DW, distilled water. The lanes of the upper panel and of the lower panel were run on the same gel, but were noncontiguous.

The expression of the c.696_698delAAG mutant allele in PSMA3 (patient 2) was similar to WT. The increased expression level of 60% for both mutant and WT allele when compared with his unaffected mother (patient 2-M), who was mutation negative in proteasome-encoding genes, may suggest compensatory induction of WT and mutant transcripts (Figure 2B). The PSMA3 c.404+2T>C splice site mutation (family 3) led to an unstable transcript (Figure 2C) due to the skipping of exon 5 (Figure 2E). The mutant transcript was only amplified with junction-specific primers spanning exons 4 and 6 in patient 3 and his mother (Figure 2F) and not in the father (patient 3-F) and was likely not expressed. Patient 3-F, who was a carrier for the PSMB8 mutation, had normal expression of the PSMA3 transcript (Figure 2C).

The early PSMB4 frameshift mutation, c.44insG, in patients 4 and 5 suggests nonexpression of the mutant allele in the 2 affected children and their unaffected father. The increased PSMB4 mRNA expression in the father carrying the mutation may suggest compensatory upregulation (Figure 2D).

Proteasome subunit mutations affect proteasome assembly and maturation in vitro.

To assess the impact of each of the novel mutations on proteasome assembly, we ectopically expressed 6 mutations, excluding those resulting in nonexpressed transcripts and the PSMB9 mutation, as V5 epitope–tagged versions from viral promoters in HeLa cells. We assayed the mutation by immunoblotting for the V5 tag in SDS and native PAGE analyses (for schematic representation of tagged subunits, see Figure 3A, and for a summary of the effects by mutation, see Supplemental Table 4).

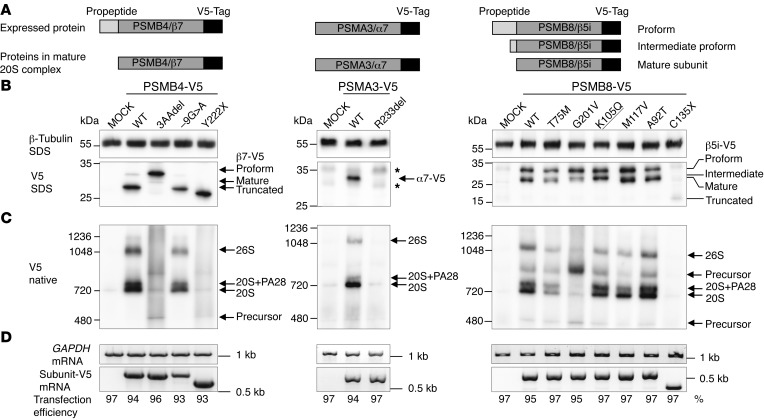

Figure 3. Maturation and incorporation of mutant proteasome subunits into proteasome complex in vitro in HeLa cells.

WT and mutant versions of the subunits PSMA3/α7, PSMB4/β7, and PSMB8/β5i/LMP7 were ectopically expressed with V5 epitope tags in HeLa cells. (A) Schematic representation of V5-tagged subunits and their maturation behavior. Of note, most of the β subunits (but not α subunits) are expressed as proforms and have to be matured by autocatalytic propeptide cleavage during proteasome assembly. Maturation of active site subunits such as β5i is a 2-step procedure resulting in proform, intermediate proform, and mature form of the subunit. (B) Immunoblot of HeLa cells transfected with V5 epitope–tagged subunits and detected by a V5-specific antibody. MOCK, empty vector backbone. Asterisks indicate unspecific background staining. β–Tubulin served as loading control. Expression of α7-R233del-V5 or β5i-C135X-V5 revealed almost no detectable protein, whereas the -9G>A mutation in β7-V5 or the β5i-T75M and -G201V mutations caused decreased protein expression. The β7-3aadel-, β5i-G201V-, -K105Q-, and -A92T-V5 versions display altered maturation of these β subunits (see accumulation of preforms or intermediate forms). (C) Incorporation of V5-tagged subunits into the proteasome complexes was assessed by native PAGE analysis and immunoblot against the V5 epitope tag. The β7-3aadel-V5 and β5i-G201V-V5 exhibit the most prominent incorporation defects. (D) With the exception of the -9G>A mutation in PSMB4-V5, all mutant subunit mRNAs were equally expressed in HeLa cells, as evaluated by RT-PCR. Expression of endogenous GAPDH mRNA served as loading control. Transfection efficiency was determined by FACS analyses of cotransfected EGFP vector. (B–D) Representative results from n = 3.

The V5-tagged p.D212_V214del mutant of β7 (present in family 1) revealed poor maturation of the β7 subunit (Figure 3B) and poor incorporation into 20S or 26S proteasomes. However, the mutated protein was detected in proteasome assembly intermediates (Figure 3C). The overall β7 protein expression of the c.-9G>A mutant protein was lower than that of WT (Figure 3, B and D), with therefore less incorporation into proteasome complexes compared with WT (Figure 3C). The accumulation of β5i-, α6-, and POMP-containing proteasome precursor complexes in patient 1 and his father’s lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) and fibroblasts confirmed the maturation defect (Supplemental Figure 3, A–C) and suggests that propeptide cleavage of the β5i subunit is impaired in mutant β7 subunits (Supplemental Figure 3B). The lower expressed but incorporated protein encoded by the –9G>A mutant gene (patient 1 and his mother) likely compensated for the failure of the paternal 3-aa–deleted β7 subunit to be incorporated into proteasomes and to be matured (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 3, A–C). The increase in free PA28 complexes indicates that both β7 mutations destabilized the interaction of 20S complexes with the PA28 regulator.

The nonsense mutation p.Y222X (patients 6 and 7, family 5) in β7 was expressed, but failed to incorporate into the 20S or 26S complexes, thus confirming the importance of the C-terminal β7 tail for proteasome assembly (Figure 3, B and C).

Protein from the V5-tagged α7 mutant p.R233del (patient 2) was not detectable in the complexes (Figure 3B), although normal transcription levels from the plasmid CMV promoter were seen (Figure 3D), suggesting that the mutant α7 was not incorporated into the 20S and the mature 26S complexes (Figure 3C). Similar to the in vitro data, in fibroblasts and LCLs from patient 2, the α7 mutation resulted in slightly reduced expression of the affected subunit (Supplemental Figure 3, B and C) and in overall reduced proteasome content. In addition, this α subunit mutation affected the binding to the PA28 regulator complex indicated by the increase in free PA28 regulator (Supplemental Figure 3A).

The novel (K105Q) and 5 previously reported β5i mutant subunits showed variable incorporation and/or maturation defects in transfected HeLa cells (Figure 3, B and C). The T75M and the G201V mutations led to decreased proteasome assembly (4, 5). The K105Q mutation caused maturation defects due to inability to completely trim the β5i propeptide (presence of intermediate band in Figure 3B), the p.M117V and p.A92T mutations displayed normal maturation and assembly (Figure 3, B and C) and only affected proteolytic activity (see below), and the truncation mutation C135X led to nonexpression of the protein, explaining its absence in all proteasome complexes (Figure 3, B and C).

We were unable to express the mutant variants of PSMB9 and POMP in HeLa cells. The truncated protein resulting from the POMP mutation (Supplemental Figure 2A) is likely unstable. POMP depletion by siRNA caused assembly defects, resulting in precursor accumulation and reduced proteasome formation with final reduced overall proteasome activity (Supplemental Figure 2, B and C).

The proteasome subunit mutations reduce proteolytic function in hematopoietic cells.

To evaluate the effect of the different mutations on proteasome function, we assessed the activity and proteasome content in patients’ hematopoietic (whole blood and EBV-transformed B cells) cells (Figure 4A and Supplemental Tables 4 and 5).

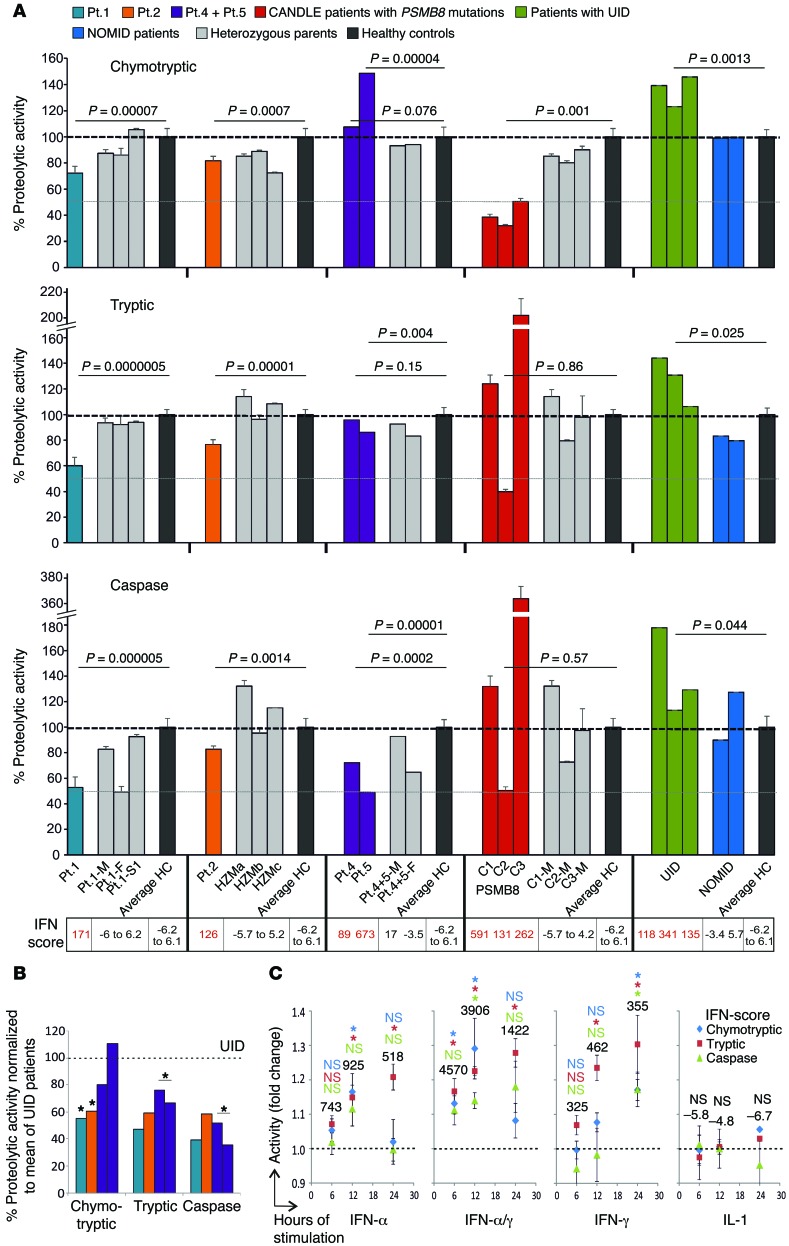

Figure 4. Proteasomal activity of PBMCs.

(A) Proteasome activity of PBMCs from CANDLE/PRAAS patients (turquoise, Pt.1; orange, Pt.2; purple, Pt.4 and Pt.5; red, CANDLE patients with PSMB8 mutations), patient family members or heterozygous carriers (gray), healthy controls (HC, black), patients with an undifferentiated interferonopathy disease who are negative for proteasome gene mutations (UID, green), and active pretreatment NOMID patients (blue) was analyzed and expressed as percentage relative to the average of healthy controls. The dashed lines indicate 100% activity. Whole blood RNA samples from the same date for patient and patient family members were analyzed by qRT-PCR for IFN-regulated gene expression and an IFN score was calculated. For patient 2, we used control samples from nonrelated heterozygous carriers for the PSMB8 T75M (HZMa, HZMb, and HZMc) for comparison. Measurements for patient 4, patient 5, and their parents were performed at only 1 time point before treatment. Patients with PSMB8 mutations, C1 (T75M/T75M), C2 (C135X/C135X), and C3 (T75M/A92T), were assessed as CANDLE controls. Two-sample, 2-tailed t tests were performed, and P values were stated. Error bars indicate technical triplicates. (B) Patient proteasome activity was normalized to the UID mean for each of the proteasome activities. Paired t test was performed. (C) PBMCs from 3 healthy donors were stimulated with the indicated cytokines or none for 6, 12, or 24 hours. The cell numbers were counted and a proteasome activity assay was done. Fold changes of activity against no-treatment control was calculated. The dashed lines on the graph indicate the activity of no-treatment controls. The numbers on top of the data points are IFN scores. Data represent mean ± SEM from n = 3 samples. Two-sample, 2-tailed t tests were performed. *P < 0.05.

As previously shown and corresponding to the β5i-active site of the proteasome, PBMCs from patients with the PSMB8 mutations, control patient C1 (T75M/T75M), and control patient C3 (T75M/A92T) had selectively impaired chymotryptic-like activity, while the patient C2, who was homozygous for the C135X-PSMB8 nonsense mutation, had reduction in all 3 proteasome activities. Patients with digenic inheritance (patients 2, 4, 5) and with the PSMB4 mutations (patient 1) had more variable proteolytic defects. PBMCs from patient 1, with 2 PSMB4 mutations, and patient 2, with 1 PSMB8 mutation and 1 PSMA3 mutation, had impairment in all 3 measured proteolytic activities (Figure 4A). Proteasome activity measured in EBV-transformed B cells from patients 1 and 2 showed a similar impairment pattern (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). PBMCs from patients 4 and 5 had severely reduced caspase-like activity consistent with the PSMB9 mutation, because WT PSMB9 confers caspase-like activity. Overall, the proteasome activities were not as severely impaired, as was seen in patients with PSMB8 mutations with chymotryptic activity impaired over 70%.

IFN stimulation increases immunoproteasome content and thus proteolytic activity (12); we therefore wanted to determine whether proteasome activity is increased in patients with other autoinflammatory diseases. We studied PBMCs from patients with the IL-1–mediated disease neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), who had no IFN signature and a normal IFN score, and from patients with undifferentiated autoinflammatory diseases (UID), who are genetically uncharacterized, but who had IFN signatures on gene-expression studies (not shown) and elevated IFN scores, suggesting chronic IFN stimulation. While proteasome function was unchanged from healthy controls in NOMID patients, all 3 proteolytic activities were increased in patients with non-CANDLE interferonopathies/UIDs. When “normalizing” the CANDLE patients’ proteolytic activities to the mean of the UID patients, the proteasome function appeared more severely impaired, indicating that CANDLE patients with digenic defects cannot appropriately upregulate proteasome activities in an IFN environment (Figure 4B). Stimulation of healthy control PBMCs with IFN-α, IFN-γ, a combination of both, or IL-1 confirmed induction of proteasome activity with IFNs, but not with IL-1 (Figure 4C).

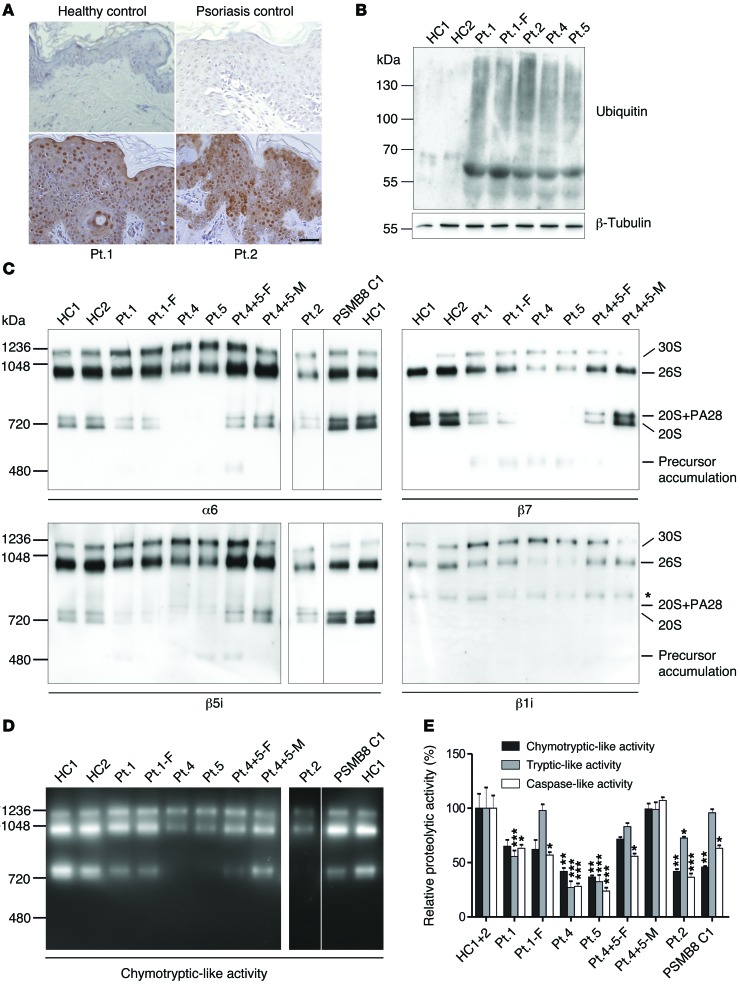

Ubiquitin aggregation and proteasome function in affected skin.

To assess proteasome assembly and function in cells of an affected tissue other than blood, we examined skin biopsies from patients 1 and 2 and primary keratinocytes from patients 1, 2, 4, and 5.

As previously observed in PSMB8-CANDLE patients (4, 5) ubiquitin staining of lesional skin biopsies from patient 1 (PSMB4 mutation) and patient 2 (PSMB8/PSMA3 mutations) showed a significant increase in ubiquitin-positive keratinocytes in comparison with healthy controls and psoriasis, a control inflammatory disorder (Figure 5A). We asked whether patients’ keratinocytes accumulated ubiquitin-rich inclusions, which were in fact increased in primary keratinocytes, as analyzed by immunoblots (patients 1, 2, 4 and 5) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Ubiquitin aggregation and proteasome profile changes in CANDLE/PRAAS patient cells.

(A) Sections from lesional skin biopsies from 2 PRAAS patients, a patient with psoriasis, and a nonlesional skin biopsy from a healthy control were stained with anti-ubiquitin antibody (Dako) for accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins (brown staining). Scale bar: 50 μm. Representative results from n = 3. (B) Insoluble fractions of RIPA cell lysates of keratinocytes were solubilized in urea lysis buffer and separated on an SDS gel followed by immunoblotting for ubiquitin. Patients show a much stronger accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in this fraction. Representative results are from n = 2. (C and D) Keratinocytes from healthy controls and CANDLE/PRAAS patients were lysed under native conditions and separated on a native gel. PSMB8 C1 denotes a CANDLE patient homozygous for PSMB8 mutation (T75M/T75M). The lanes for patient 2, PSMB8 C1, and HC1 were run on the same gel, but were noncontiguous. n = 1. (C) Immunoblotting was performed for α6 and β5i. Patient samples harboring β7 and/or β1i mutations were also immunoblotted for β7 and β1i. Asterisk indicates unspecific crossreaction of β1i antibody (Abcam). (D) An in-gel overlay experiment was performed for chymotryptic-like activity to visualize the activity of the proteasome. (E) Plate reader activity assay was measured from whole keratinocyte cell lysates. Patients show a strong reduction in 2 or 3 protease activities. Each of the 5 patients’ and 3 parents’ samples were normalized against HC1+2. Means were estimated from the triplicate values on the normal controls (n = 2). Data were analyzed by restricted maximum likelihood mixed models methods, using the xtmixed procedure in Release 12 of the software package Stata (StataCorp). Data represent the mean ± SD from technical triplicates. n = 1. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Next, we assessed proteasome formation and estimated the amount of proteasome content in keratinocytes. Consistent with the experiments in transfected HeLa cells and in patients’ hematopoietic cells and fibroblasts (Figure 3, Figure 4A, and Supplemental Figures 3 and 4), proteasome assembly in keratinocytes was impaired with accumulation of proteasome precursor complexes in patient 1 and his father (patient 1-F) as well as in patients 4 and 5 (Figure 5C). Patient 2 displayed a general decrease in the total proteasome content in fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Proteasome impairment in these patients (Figure 5, D and E) was due to altered proteasome assembly and failed subunit incorporation.

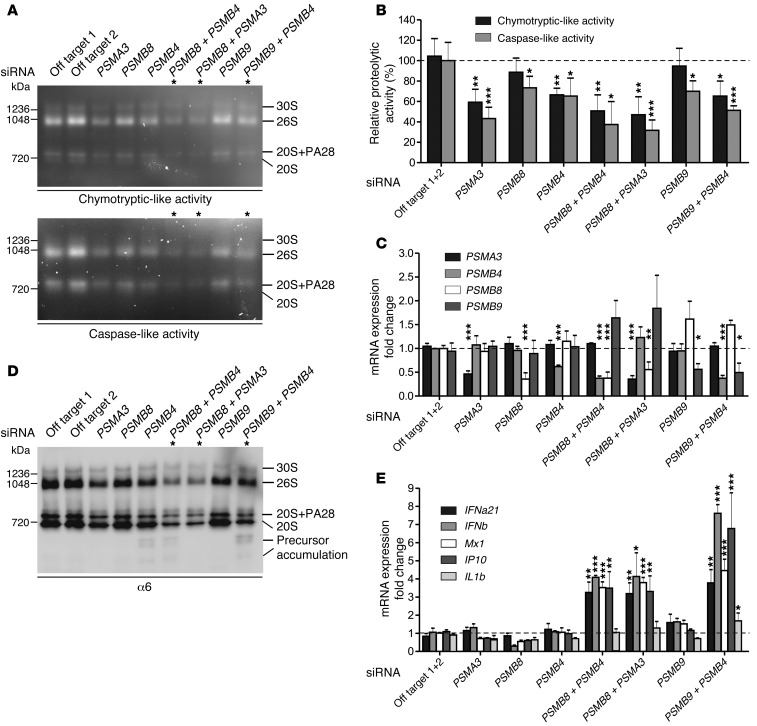

Recapitulation of additive effect of proteasome defects on proteolytic function and type I IFN induction in siRNA knockdown experiments in primary fibroblasts.

To further confirm the digenic effects of the proteasome subunit mutations on proteasome formation and function, we used healthy fibroblasts and silenced mRNA expression of PSMA3, PSMB4, PSMB8, and PSMB9 by siRNA in single knockdown experiments or we knocked down combinations thereof that were occurring in patients, PSMA3/PSMB8, PSMB4/PSMB8, or PSMB4/PSMB9, respectively. As expected, knockdown of a single proteasome subunit mRNA caused a slight decrease in the chymotryptic- or caspase-like activity of the proteasome due to decreased total proteasome amounts in comparison with cells treated with off-target siRNA as controls (Figure 6, A–C). The depletion of the standard subunits α7 or β7 affected the system more (35%–40% decrease) than depletion of 1 of the 2 immunosubunits, β1i or β5i (10%–20%). However, additive depletion of 2 proteasome subunits by siRNA led to more severe assembly defects and decreases in proteolytic function, which is consistent with our concept of digenic inheritance causing additive proteasome defects. In healthy control fibroblasts treated with siRNAs targeting the expression of 2 different subunits, a stronger decrease of proteasome assembly (Figure 6D) and of their proteolytic activity (up to 70% decrease) was observed (Figure 6, A and B). Knockdown controls for the respective mRNAs by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) showed an approximately 60% to 40% efficiency, respectively.

Figure 6. Additive depletion of proteasome subunits by siRNA simulated the digenic inheritance of proteasome mutations in patients.

Primary human fibroblasts were depleted for PSMB8, PSMB4, PSMA3, or PSMB9 as well as combinations thereof: PSMB8 plus PSMB4; PSMB8 plus PSMA3; PSMB9 plus PSMB4 by siRNA. The following siRNA concentrations were used: off-target 1, off-target 2, PSMA3, PSMB8, and PSMB9 (10 nM); PSMB4 (15 nM). (A and D) Representative results from n = 3. (A) Native PAGE substrate overlays with lysates of siRNA-treated cells show reduction of proteasome activity. (B) Quantification of native PAGE substrate overlays. (C) Knockdown control for the respective genes with qRT-PCR shows approximately 60% to 40% efficiency, respectively. (D) Immunoblot stained for α6 shows decreased total amount of proteasomes. In cells treated with siRNAs targeting the expression of 2 different subunits. a stronger decrease of proteasomes and their activity was observed. (E) mRNA expression of type I IFN and IFN-regulated genes MX1 and IP10 was significantly upregulated in cells treated with 2 different proteasomal siRNAs as assayed by qRT-PCR. All data in bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. n = 3. Samples were normalized against off-target siRNA 1+2. Paired t tests were performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Moreover, the additive depletion of 2 proteasome subunits in the combinations found in CANDLE/PRAAS patients led to the induction of type I IFN (shown for IFNA21 encoding IFNα21 and IFNB1 encoding IFNβ), but not type II IFN (IFNG mRNA was not detectable in any of the samples) (Figure 6E). A single knockdown of a proteasome subunit mRNA even to about 50% of WT did not significantly induce transcription of IFNB1, MX1, IP10 (also known as CXCL-10), or IL1B genes. In contrast, additive targeting of 2 subunits resulted in specific induction of type I IFN genes exemplified by IFNB1 and IFNA21 as well as the IFN-inducible genes MX1 and IP10, whereas IL1B was not significantly induced (Figure 6E). This effect is not caused by cellular siRNA responses, because increasing amounts of off-target siRNA do not induce IFN gene transcription in the concentrations used in the double-knockdown siRNA experiments (Supplemental Figure 5, A and B). These experiments mimic the additive effect of 2 different proteasome subunit mutations and reproduce the induction of type I IFN that we observed in the digenic CANDLE/PRAAS patients.

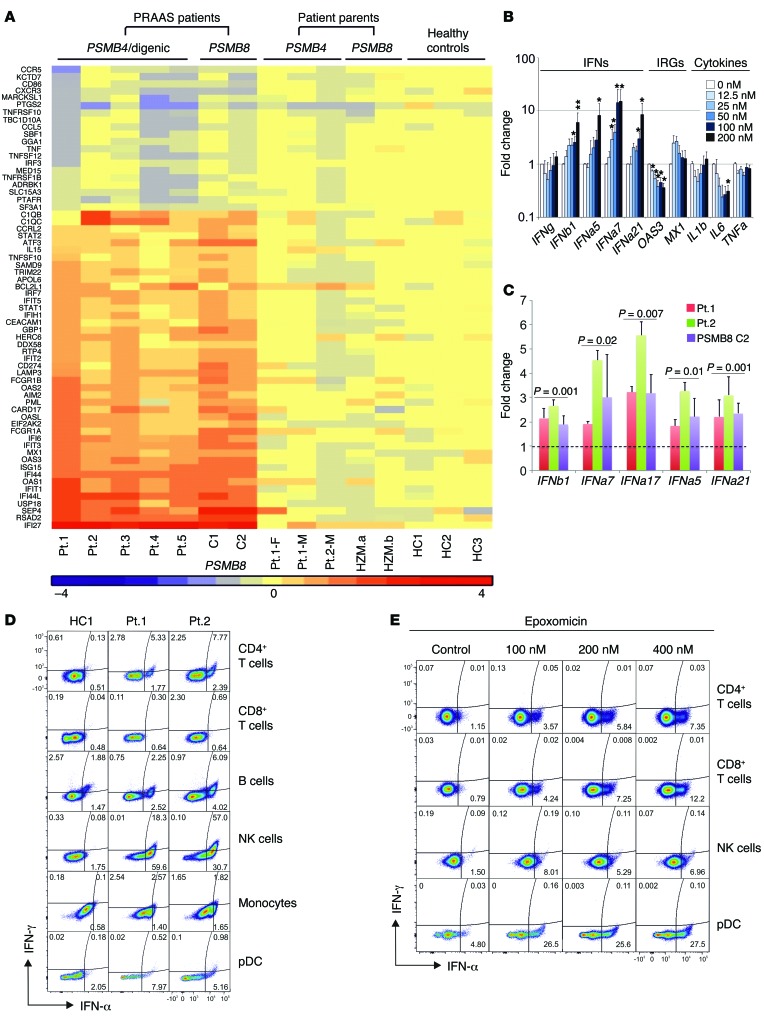

Proteasome dysfunction leads to type I IFN induction.

A strong IFN gene expression signature was present in all patients irrespective of their mutations (Figure 7A). The secretion of IFN-stimulated chemokines (IP-10, MCP-1, MIG) and cytokines (IL-18) that are detected early in viral infections (22, 23) was significantly increased in CANDLE patients compared with relatives, controls, or NOMID patients (IP-10, P < 0.001; MCP-1, P < 0.01; MIG, P < 0.01; and IL-18, P < 0.01). In NOMID, IL-18 is increased due to constitutive inflammasome activation and not IFN signaling (Supplemental Figure 6A).

Figure 7. Type I IFN induction in patients’ PBMCs and fibroblasts and in healthy control PBMCs treated in vitro with proteasome inhibitors.

(A) RNAseq was performed on whole-blood RNA. Differentially expressed genes in CANDLE/PRAAS patients (fold change > 2, P < 0.05) were analyzed by Ingenuity, and IFN-regulated genes were plotted on the heat map. (B) PBMCs from healthy controls were treated with indicated concentrations of the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin for 24 hours. Expression of IFN genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Fold change was calculated for each condition relative to the mean of no-treatment controls. Data represent mean ± SEM. n = 8 for IFN genes and 200 nM concentration; n = 5 for all other concentrations; n = 4 for OAS3, MX1, and IL1B; n = 3 for IL6 and TNFA. Paired t tests were done using ΔCt values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (C) Expression levels of IFNB1, IFNA7, IFNA17, IFNA5, and IFNA21/1 from 3 CANDLE/PRAAS patients and 4 healthy donors were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated over the average of 4 healthy controls. Data represent mean ± SEM. n = 3. Two-sample t tests were performed. P values are stated. (D) Expression of IFNs from whole blood of 2 active CANDLE patients (patient 1 and patient 2) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Expression of IFNs in PBMCs from a healthy donor treated with the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin at indicated concentrations was analyzed by flow cytometry. (D and E) Representative results from n = 3 and n = 2, respectively.

It remains unclear whether the IFN signature is induced by intrinsic or extrinsic factors in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells in CANDLE patients. To confirm the observation in the siRNA knockdown experiments, we used 2 proteasome inhibitors, epoxomicin and bortezomib, to chemically induce global proteasome impairment in PBMCs and fibroblasts. Treatment of PBMCs and fibroblasts with either inhibitor elicited dose-dependent increases in IFNA and IFNB transcription as well as transcription of IFN-stimulated genes (IP10 or MX1), but did not affect transcription of cytokine genes (IL1, TNF, and IL6) (Figure 7, B and C, and Supplemental Figure 6, C and D), in agreement with the siRNA experiments (Figure 6). To determine the cellular origin of type I IFNs in PBMCs, FACS staining for IFN-α and IFN-γ confirmed that mainly type I IFN, but not type II IFN, is upregulated in patients’ NK and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) (performed in patients 1 and 2) (Figure 7D). We also assessed IFNG transcription in different cell populations; while it was very low or undetectable in fibroblasts, IFN-γ staining was increased in sorted NK cells from active CANDLE patients (Supplemental Figure 6B). Blockade of proteasome function in healthy control cells (NK cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and pDCs) showed consistently more IFN-α–positive cells (Figure 7E), which was even observed in NK cells. As stimulation with both cytokines, IFN-α and IL-18, induces IFN-γ production in NK cells (24), the increase in IFN-γ production observed in patients’ NK cells is likely secondary, rather than directly caused by proteasome dysfunction.

In addition, we observed alterations in B cell subsets as well as a higher percentage of naive T cells and immature neutrophils in CANDLE patients (Supplemental Figure 6, E–G). This is in agreement with previous work suggesting that immunoproteasome impairment in mice is linked to changed cytokine patterns (17, 25) and altered T cell expansion and maintenance (12, 26).

In summary, our studies suggest that monogenic and digenic mutations in proteasome subunits cause assembly defects or impaired proteolytic activity along with an inability to appropriately upregulate immunoproteasome content or function when required in response to proteotoxic stress. Our data show that proteasome dysfunction is associated with increased predominantly IFN type I production both in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells, providing further clues to the pathomechanisms of CANDLE.

Discussion

The findings that the CANDLE/PRAAS disease spectrum is caused by recessively inherited loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the inducible proteasome subunit PSMB8 (3, 4, 5, 11, 27) suggested that CANDLE/PRAAS may be an “immunoproteasome disease.” Our genetic data showing that mutations in inducible and constitutive proteasome subunits can cause CANDLE/PRAAS illustrate that WES should supersede targeted sequencing of proteasome genes in patients with suspected CANDLE/PRAAS in whom only one or no definite mutation is identified in the PSMB8 gene. Our functional data further suggest that global proteasome dysfunction rather than specific immunoproteasome dysfunction leads to the disease.

While the absence of inducible proteasome subunits is tolerated in mice, the presence of constitutive proteasome subunits is essential (28). Consistent with these observations, a homozygous truncation mutation in PSMB8 causes complete β5i deficiency with an intermediate CANDLE phenotype (6); however, we have not found homozygous truncation mutations in the constitutive subunits. Either mutations in the constitutive α7 and β7 subunits are hypomorphic and result in the expression of mutant proteins with residual protein function, which may be critical for survival, as we see in patient 1, who is compound heterozygous for PSMB4 mutations, or the mutations that lead to nonexpression are only present as monoallelic variants (patients 4 and 5).

The finding of digenic mutations as a cause of CANDLE and the absence of clinical disease in heterozygous parents was initially puzzling; however, the calculated statistical probabilities of assembling WT versus mutant proteasome complexes could explain this discrepancy. Assuming mutant subunits are competent for assembly, a heterozygous carrier (parent or sibling) would assemble 25% of proteasomes with WT subunits, 50% with 1 mutant subunit, and 25% with 2 mutant subunits. In contrast, CANDLE patients with double-heterozygous mutation (digenic) inheritance would assemble only 6.25% proteasomes with no mutant subunits, 62.5% of proteasomes would have 1 or 2 mutant subunits, and 31.25% would have 3 or 4 mutant subunits (Supplemental Figure 7). The POMP mutation likely causes haploinsufficiency, which is supported by previous findings that an approximately 50% reduction of POMP levels is sufficient to cause impaired proteasome activity and cell death in vitro (14, 29). The additive effect of 2 different subunit mutations was mimicked by siRNA knockdown experiments of 2 proteasome subunits, which led to a more severe reduction in proteasome assembly and proteolytic function than knockdown of a single proteasome subunit, thus verifying the concept of digenic inheritance. Together, the genetic data suggest that impairment of the proteasome assembly and/or function caused by mutations in various proteasome components can lead to clinical disease. Other examples of digenic inheritance include conditions caused by double-heterozygous variants of structural proteins that are critical for organ function, including retinitis pigmentosa (30), the digenic inheritance of nonsyndromic deafness (31), Usher’s syndrome (32), Bartter syndrome (33), and Hirschsprung’s disease (34), and triallelic inheritance was found in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) (35) and in isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (36). In 2 recently described digenic conditions, the second gene acts as epigenetic or epistatic modifier, as observed in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) (37) and in ataxia, dementia, and hypogonadotropism (38), respectively. The advent of next-generation sequencing will likely increase the power to identify new diseases with digenic/oligogenic inheritance.

β5i deficiency in mice causes no spontaneous phenotype; however, immunoproteasome formation is pivotal for the maintenance of proteostasis and the preservation of cell viability in tissues when exposed to inflammatory insults. In mouse inflammation models, cytokines, particularly IFNs, trigger the production of radicals, which induce oxidant-damaged proteins and the formation of ubiquitin-rich inclusions (39). The clearance of these inclusions in cells of the central nervous system and of the periphery is dependent on the induction of immunoproteasomes with their increased proteolytic capacity that is necessary to prevent IFN-induced cell death (9, 12, 16, 17, 40). The data in murine models suggest that, while WT cells can adapt to an increased demand for protein degradation through the induction of immunoproteasomes, in mutant cells, there seems to be a threshold at which cells start a survival program followed by apoptotic cell death when the capacity to clear inclusions becomes too low.

We assessed proteasome function and the ability to upregulate proteasome function in our patients. In all CANDLE/PRAAS patients, regardless of their proteasome subunit mutations, the proteasome function is impaired because the mutation-induced subunit defects lead to lower expression and/or impaired proteasome assembly. The impairment in proteolytic function is not limited to chymotrypsin-like activity, as was previously seen in patients with mutations in PSMB8 (3), but affects trypsin- and caspase-like activity, depending on the respective proteasome subunits that are mutated. A limitation of the assay includes the use of whole-cell lysates, as the assessed proteolytic activities are not absolutely proteasome specific; however, the in-gel assays confirmed the localization of the proteolytic activities to the proteasome complexes. Although at least one of the proteasome activities in patients was consistently lower than that of healthy controls, the assay does not distinguish some heterozygous, clinically unaffected parents from a patient, as the impaired proteolytic activities of some unaffected carriers may be similar to those of an affected child. However, the patients’ proteasome activity may be maximally upregulated because of the chronic IFN stimulation, while the unaffected carriers who do not have evidence of chronic IFN upregulation do not upregulate proteasome function through the IFN mechanism. The fact that CANDLE patients have chronically high IFN stimulation, as assayed by the persistently high IFN response signature, indicates that we are comparing patient and unaffected carrier under different conditions. The proteolytic function measured in the patients may therefore not reflect the full extent of the impact of the proteasome defect. When we compared proteasome function in CANDLE patients with proteasome activity in patients with other IFN-mediated autoinflammatory syndromes who do not have proteasome subunit mutations, we found increased proteolytic activities in PBMCs from patients with non-CANDLE interferonopathies for all 3 proteolytic activities tested. The increase in proteasome activity was not seen in cells from untreated, clinically active, and symptomatic NOMID patients, whose disease is caused by chronic constitutive IL-1 production and stimulation (41). These findings are consistent with previously published data and our current data showing that type I and type II IFN, but not IL-1, induce proteasome subunit upregulation and proteasome function. The measurement of proteasome activity in patients with an interferonopathy may thus be a useful diagnostic tool in addition to genetic and molecular diagnostics to distinguish patients with a proteasome defect from patients with similar clinical phenotypes who do not have CANDLE/PRAAS.

The presence and persistence of the IFN-response gene signature in CANDLE (6) regardless of the causative proteasome subunit mutation raises the question of the molecular mechanism that links proteasome dysfunction to IFN production. Our functional data in PBMCs and fibroblasts show that type I IFN transcription is induced in a dose-dependent fashion upon global inhibition of proteasome function with chemical inhibitors and in siRNA knockdown experiments, suggesting that global proteasome dysfunction induces type I IFN transcription. The cellular origin of the type I IFN transcription/production is ubiquitous. Upregulation of type I IFN and not type II IFN was seen in all major sorted white blood cell populations and in primary fibroblasts from patients. The chronic induction of a type I IFN signature in CANDLE/PRAAS patients and not the heterozygous controls likely indicates that patients’ cells have reached a level of cumulative proteasome defects that caused increased cell stress and thus the transcription of type I IFNs. We observe an accumulation of ubiquitin-rich inclusions in patients’ keratinocytes, which leads to cell stress in murine models. Whether these inclusions directly trigger type I IFN gene transcription remains unknown. However, the inability to clear damaged proteins and the concomitant induction of type I IFNs may cause a vicious cycle of further induction of protein damage and impaired clearance and explain the severe inflammatory phenotype of CANDLE/PRAAS (42). This hypothesis is preliminarily supported by our initial observation of clinical improvement with treatment with JAK inhibitors that can block IFN signaling and thus the production of radicals (NCT01724580).

The IFN signature in CANDLE/PRAAS patients is similar to that seen in patients with Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS) (43) and in patients with STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) (35). In patients with AGS, the genetic defects cause loss of function in nucleases and enzymes associated with nucleic acid metabolism that are thought to lead to the accumulation of nucleotides in animal models and patient cells (44). The IFN signature in both AGS and SAVI is dependent on STING (35, 37). However, the signaling pathway inducing type I IFNs in CANDLE is not STING dependent, as proteasome inhibition in Sting–/– cells still leads to the induction of type I IFN transcription (Yin Liu, our unpublished data). Chemical proteasome inhibition is known to induce ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Along with the strong IFN signature in CANDLE patients (6), we found the induction of some genes that are typically upregulated in an ER stress response (Yin Liu, our unpublished data).

Although more work is needed to decipher the exact molecular mechanism of proteasome dysfunction and type I IFN transcription, our data suggest that the induction of type I IFN and the presence of the IFN signature in CANDLE indicate cell stress that likely drives disease pathogenesis. The understanding of the exact molecular pathways that link proteotoxic stress to type I IFN production will likely result in the identification of novel therapeutic targets not only for patients with CANDLE/PRAAS, but also for those with a growing spectrum of inflammatory diseases that are caused by the generation of intracellular stress that is coupled with IFN production.

Methods

Patients.

The present study includes 8 patients with clinical disease manifestations consistent with CANDLE who were negative (n = 4) or heterozygous for PSMB8 mutations (n = 4) (Supplemental Table 1). We used 3 CANDLE patients (C1–C3) with known PSMB8 mutations, 7 NOMID patients, and 3 uncharacterized IFN-mediated autoinflammatory disease (UID) patients as disease controls, parents heterozygous for a PSMB8 mutation, and controls from the blood bank as healthy controls.

Cell lines.

The primary keratinocyte, primary fibroblast, and EBV-immortalized B cell lines used in the paper were generated from skin biopsies or blood draws from patients, their parents, and healthy controls at the NIH after obtaining consent; standard protocols were used to generate the cell lines.

In silico modeling of novel mutations.

Homology models were built based on x-ray structures of the mouse immunoproteasome (PDB entry code 3UNH) (20) for mutations in PSMA3, PSMB8, PSMB9 or from the bovine 20S proteasome (1IRU) for mutations in PSMB4 (19) using the SWISS-PDB viewer (45). The initial models were energetically minimized with GROMOS 43B1 force field (39) to avoid local distortions and visualized with PYMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger LLC).

Proteasome activity assay.

Frozen PBMCs were thawed in a 37°C water incubator and resuspended in 10% FCS RPMI 1640 at about 2 × 106/ml. Six hours later, cell numbers were counted and proteasome activities were measured with Proteasome-Glo cell-based assay kit (Promega). Chymotryptic-like, tryptic-like, and caspase-like activities were measured separately following the company’s recommended protocol. 4 × 104 cells per well were used. Average proteasome activity of the healthy pediatric and adult PBMCs was set as 100%, and proteasome activity of all other PBMC samples was calculated as percentage relative to the average of controls. EBV-B cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, and 1× MEM NEAA (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Keratinocytes were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with pituitary extract (25 μg/ml), epidermal growth factor (0.15 ng/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml), 1× penicillin/streptomycin, and fungizone (0.5 μg/ml) (Invitrogen). Cell pellets were gently lysed in TSDG buffer with 3 freeze-thaw cycles to prevent denaturation. 10 μg cell lysates were assayed in triplicate for protease activity in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP with either 40 μM Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-aminomethylcoumarin (Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC) for chymotryptic-like activity, BZ-Val-Gly-Arg-AMC for tryptic-like activity, or Z-Leu-Leu-Glu-AMC (Bachem) for caspase-like activity. Release of free AMC after substrate digestion was maintained by UV excitation. For in-gel activity measurements, equal amounts of protein extracts and purified 26S proteasome (see below for immunoblots) were separated on native PAGE (3%–12%, Invitrogen) and monitored after 100 mM fluorogenic peptide (as mentioned above) incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C on a Fusion FX Imager (Peqlab).

Immunoblots, proteasome assembly.

Equal amounts of TSDG-buffered protein extracts from EBV-B cells, patients’ keratinocytes, patients’ fibroblasts, siRNA-treated fibroblasts, or transfected HeLa cells were separated on SDS-Laemmli gels (15%) or native PAGE (3%–12%, Invitrogen) and immunoblotted for proteasome subunits as indicated. Primary antibodies were as follows: α6, β1i (LMP2), β5i (LMP7), and POMP are laboratory stocks and were used in former studies (15, 16); PA28β (Cell Signaling, 2409); α7 (Cell Signaling, 2456S); β7 (Abcam, ab137087), V5 [Invitrogen, R960(1)]; β-tubulin (Covance, MMS-410P); β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., sc-47778); and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., sc-25778)). As internal control, purified 26S proteasome from erythrocytes was used (laboratory stock).

Ubiquitin blots were performed after cell lyses of keratinocytes in RIPA buffer. The insoluble fraction was lysed in urea lysis buffer (7 M urea, 4 M thiourea, 4% m/v chaps). Equal amounts of urea lysate corresponding to the protein content of the RIPA lysate were separated on SDS-Laemmli gels (10%) and immunoblotted for ubiquitin (Dako, Z0458).

siRNA treatment.

Fibroblasts were cultured in basal Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with 10% FCS and glutamin. Concurrent with seeding, cells were transfected with siRNAs using X-tremeGENE siRNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) on 6-well plates. The following siRNAs were used: Dharmacon ON-Target plus SMARTpool for PSMA3 (L-011758-00), PSMB4 (L-01136200), PSMB8 (L-006022-00), PSMB9 (L-006023-00), Dharmacon control pool (D-001810-10-20), and QIAGEN All Stars Negative Control (1027280). The concentrations of the siRNAs are indicated in the legend of Figure 6. After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, cells were harvested and used for RNA extraction and native cell lysis.

IFN score calculation.

The mRNA expression levels for IFI27, IFI44L, IFI44, RSAD2, ISG15, and USP18 were quantified by qRT-PCR (TaqMan, Applied Biosystems) and normalized to 18S. Gene-expression levels were expressed as fold changes relative to a healthy control. IFN score for each gene was calculated as the difference between the sample and the average of healthy controls divided by the SD of the healthy controls (40). The sum of the scores for all the genes was used as the score for the sample.

Polyubiquitinated protein staining.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections from skin biopsies of a healthy individual, a patient with psoriasis, and two CANDLE patients were first deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then stained with anti-ubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., sc-166553) at a 1:3,200 dilution, followed by incubation with HRP polymer-conjugated anti-rabbit system (Golden Bridge). Stained slides were viewed on a Leica DMR microscope equipped with a Leica DFC500 camera. Images were acquired with Leica Firecam software at ×25 magnification.

Methods for RNA sequencing, Luminex assay, Sanger sequencing and whole-exome sequencing, qRT-PCR, cloning and transfection of expression vectors, and FACS analysis are described in the Supplemental Methods. Consistent with the patients’ consent, we will make the WES and RNAseq data to researchers upon request.

Statistics.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize group differences between patients and healthy controls or disease controls. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 12 (StataCorp). In some experiments, paired t tests of the stimulated to baseline ratios or logs of ratios were compared (Figure 4C, Figure 6, B, C, and E, Figure 7B, Supplemental Figure 5, A and B, and Supplemental Figure 6, C and D). In other experiments, we used a 2-sample t test, either the standard or Welch’s version, to compare standardized values of cytokines between patients with similar mutations and either healthy controls or appropriate disease controls (undifferentiated interferonopathies without a proteasome defect) (Figure 4, A and B, Figure 7C, Supplemental Figure 4A, and Supplemental Figure 6B). We also used 2-sample t tests of serum concentrations or percentages of cell subsets to compare various groupings of patients, heterozygous parents, healthy controls, or NOMID patients (disease control) (Supplemental Figure 6, A and E–G). In 1 experiment we compared standardized values for individual patients or parents separately with a population of healthy controls (Figure 5E) using mixed models. In Supplemental Figure 6A, the P values comparing CANDLE 3 distinct control groups are unadjusted. All statistical tests were 2 tailed. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Study approval.

The study was approved by the NIDDK/NIAMS Institutional Review Boards at the respective sites, and written informed consent was obtained from the subjects or their parents. A separate written informed consent document was provided for photographs appearing in the manuscript.

Author contributions

AB and YL conducted experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; AS, BM, EQ, QZ, AB, AdJ, MP, WLT, EFR, LK, JJC, JB, YC, and YH conducted experiments and contributed to the interpretation of the data; FS, SM, MG, and PM analyzed and interpreted data; GSM, AR, SH, HK, HJL, AM, RDC, DB, AVC, LG, DC, DS, AT, AZ, KR, and PB conducted patient care and clinical data collection; RW conducted statistical analyses; CCRL and DLK conducted data interpretation; PWH conducted in silico modeling; IA designed and oversaw genetic analyses; EK designed the research study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; RGM oversaw the project, patient care, and evaluation, designed the research study, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following colleagues for their help: Christina Zaal and Evelyn Ralston for microscopy images, Hong-Wei Sun and Stephen Brooks for gene-expression analysis, Nigel Klein for proteolytic functional work on patients 4 and 5, Clarissa Pilkington for clinical recruitment of patients 6 and 7, Mirna Hashem Medly, Elon Pras for the Palestinian control samples, Nicole Plass and Michelle O’Brien for patient care, and Daniela Ludwig for technical help on siRNA experiments. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAMS at the NIH, by the Berlin Institute of Health, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB TR 43 to E. Krüger, SFB740 to E. Krüger and P.W. Hildebrand).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2015;125(11):4196–4211. doi:10.1172/JCI81260.

References

- 1.Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R. Autoinflammatory disease reloaded: a clinical perspective. Cell. 2010;140(6):784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jesus AA, Canna SW, Liu Y, Goldbach-Mansky R. Molecular mechanisms in genetically defined autoinflammatory diseases: disorders of amplified danger signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:823–874. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal AK, et al. PSMB8 encoding the beta5i proteasome subunit is mutated in joint contractures, muscle atrophy, microcytic anemia, and panniculitis-induced lipodystrophy syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(6):866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arima K, et al. Proteasome assembly defect due to a proteasome subunit beta type 8 (PSMB8) mutation causes the autoinflammatory disorder, Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(36):14914–14919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106015108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitamura A, et al. A mutation in the immunoproteasome subunit PSMB8 causes autoinflammation and lipodystrophy in humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4150–4160. doi: 10.1172/JCI58414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, et al. Mutations in PSMB8 cause CANDLE syndrome with evidence of genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):895–907. doi: 10.1002/art.33368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg AL. Functions of the proteasome: from protein degradation and immune surveillance to cancer therapy. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(pt 1):12–17. doi: 10.1042/BST0350012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea through the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10(1–4):7–22. doi: 10.1159/000334283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruger E, Kloetzel PM. Immunoproteasomes at the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses: two faces of one enzyme. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MG, Driscoll J, Monaco JJ. Structural and serological similarity of MHC-linked LMP and proteasome (multicatalytic proteinase) complexes. Nature. 1991;353(6342):355–357. doi: 10.1038/353355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluk J, et al. Chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature syndrome: a report of a novel mutation and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(1):215–217. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebstein F, Kloetzel PM, Kruger E, Seifert U. Emerging roles of immunoproteasomes beyond MHC class I antigen processing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(15):2543–2558. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0938-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aki M, et al. Interferon-gamma induces different subunit organizations and functional diversity of proteasomes. J Biochem. 1994;115(2):257–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heink S, Ludwig D, Kloetzel PM, Kruger E. IFN-gamma-induced immune adaptation of the proteasome system is an accelerated and transient response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9241–9246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501711102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fricke B, Heink S, Steffen J, Kloetzel PM, Kruger E. The proteasome maturation protein POMP facilitates major steps of 20S proteasome formation at the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(12):1170–1175. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert U, et al. Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell. 2010;142(4):613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opitz E, et al. Impairment of immunoproteasome function by beta5i/LMP7 subunit deficiency results in severe enterovirus myocarditis. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9): doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Megarbane A, Sanders A, Chouery E, Delague V, Medlej-Hashim M, Torbey PH. An unknown autoinflammatory syndrome associated with short stature and dysmorphic features in a young boy. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(5):1084–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unno M, et al. The structure of the mammalian 20S proteasome at 2.75 A resolution. Structure. 2002;10(5):609–618. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin TA, et al. Immunoproteasome assembly: cooperative incorporation of interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-inducible subunits. J Exp Med. 1998;187(1):97–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos PC, Marques AJ, London MK, Dohmen RJ. Role of C-terminal extensions of subunits β2 and β7 in assembly and activity of eukaryotic proteasomes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(14):14323–14330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Julkunen I, Melen K, Nyqvist M, Pirhonen J, Sareneva T, Matikainen S. Inflammatory responses in influenza A virus infection. Vaccine. 2000;19(suppl 1):S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padovan E, Spagnoli GC, Ferrantini M, Heberer M. IFN-α2a induces IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 production in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and enhances their capacity to attract and stimulate CD8+ effector T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(4):669–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matikainen S, et al. IFN-α and IL-18 synergistically enhance IFN-γ production in human NK cells: differential regulation of Stat4 activation and IFN-γ gene expression by IFN-α and IL-12. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(7):2236–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muchamuel T, et al. A selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 blocks cytokine production and attenuates progression of experimental arthritis. Nature Med. 2009;15(7):781–787. doi: 10.1038/nm.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhtreiber WM, Hayashi T, Dale EA, Faustman DL. Central role of defective apoptosis in autoimmunity. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31(3):373–399. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermott A, et al. A case of proteasome-associated auto-inflammatory syndrome with compound heterozygous mutations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(1):e29–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez CK, Monaco JJ. Homology of proteasome subunits to a major histocompatibility complex-linked LMP gene. Nature. 1991;353(6345):664–667. doi: 10.1038/353664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glynne R, Powis SH, Beck S, Kelly A, Kerr LA, Trowsdale J. A proteasome-related gene between the two ABC transporter loci in the class II region of the human MHC. Nature. 1991;353(6342):357–360. doi: 10.1038/353357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kajiwara K, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Digenic retinitis pigmentosa due to mutations at the unlinked peripherin/RDS and ROM1 loci. Science. 1994;264(5165):1604–1608. doi: 10.1126/science.8202715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Castillo I, et al. A deletion involving the connexin 30 gene in nonsyndromic hearing impairment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):243–249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng QY, et al. Digenic inheritance of deafness caused by mutations in genes encoding cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(1):103–111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlingmann KP, et al. Salt wasting and deafness resulting from mutations in two chloride channels. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1314–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auricchio A, et al. Double heterozygosity for a RET substitution interfering with splicing and an EDNRB missense mutation in Hirschsprung disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(4):1216–1221. doi: 10.1086/302329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katsanis N, et al. Triallelic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a Mendelian recessive disorder. Science. 2001;293(5538):2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1063525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitteloud N, Durrani S, Raivio T, Sykiotis GP. Complex genetics in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Front Horm Res. 2010;39:142–153. doi: 10.1159/000312700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemmers RJ, et al. Digenic inheritance of an SMCHD1 mutation and an FSHD-permissive D4Z4 allele causes facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1370–1374. doi: 10.1038/ng.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margolin DH, et al. Ataxia, dementia, and hypogonadotropism caused by disordered ubiquitination. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1992–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fehling HJ, et al. MHC class I expression in mice lacking the proteasome subunit LMP-7. Science. 1994;265(5176):1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.8066463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebstein F, et al. Immunoproteasomes are important for proteostasis in immune responses. Cell. 2013;152(5):935–937. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldbach-Mansky R, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):581–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brehm A, Kruger E. Dysfunction in protein clearance by the proteasome: impact on autoinflammatory diseases. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37(4):323–333. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rice GI, et al. Assessment of interferon-related biomarkers in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome associated with mutations in TREX1, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, and ADAR: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(12):1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70258-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volkman HE, Stetson DB. The enemy within: endogenous retroelements and autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(5):415–422. doi: 10.1038/ni.2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository: new features and functionalities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D315–D318. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huber EM, et al. Immuno- and constitutive proteasome crystal structures reveal differences in substrate and inhibitor specificity. Cell. 2012;148(4):727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.