Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Incomplete gallbladder removal following open and laparoscopic techniques leads to residual gallbladder stones. The commonest presentation is abdominal pain, dyspepsia and jaundice. We reviewed the literature to report diagnostic modalities, management options and outcomes in patients with residual gallbladder stones after cholecystectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Medline, Google and Cochrane library between 1993 and 2013 were reviewed using search terms residual gallstones, post-cholecystectomy syndrome, retained gallbladder stones, gallbladder remnant, cystic duct remnant and subtotal cholecystectomy. Bibliographical references from selected articles were also analyzed. The parameters that were assessed include demographics, time of detection, clinical presentation, mode of diagnosis, nature of intervention, site of stone, surgical findings, procedure performed, complete stone clearance, sequelae and follow-up.

RESULTS:

Out of 83 articles that were retrieved between 1993 and 2013, 22 met the inclusion criteria. In most series, primary diagnosis was established by ultrasound/computed tomography scan. Localization of calculi and delineation of biliary tract was performed using magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. In few series, diagnosis was established by endoscopic ultrasound, intraoperative cholangiogram and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic techniques and open surgery were the most common treatment modalities. The most common sites of residual gallstones were gallbladder remnant, cystic duct remnant and common bile duct.

CONCLUSION:

Residual gallbladder stones following incomplete gallbladder removal is an important sequelae after cholecystectomy. Completion cholecystectomy (open or laparoscopic) is the most common treatment modality reported in the literature for the management of residual gallbladder stones.

Keywords: Cystic duct remnant, gallbladder remnant, post-cholecystectomy syndrome, residual gallstones, retained gallbladder stones, subtotal cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now the gold standard for treatment of symptomatic gallstones. In some patients however the symptoms may persist even after surgery. These include upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia with or without jaundice. A small percentage of patients with post-cholecystecomy syndrome are symptomatic due to a residual stone in a particularly long cystic duct or to the relapse of lithiasis in a gallbladder remnant.[1,2]

Incidence of incomplete gallbladder removal following conventional cholecystectomy appears very low.[3,4] In the laparoscopic era, incidence of unintentional incomplete gallbladder removal has not been reported clearly though it seems to be slightly more than the ones reported with open cholecystectomy.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] Incomplete resection of gallbladder occurs in up to 13.3% of laparoscopic cholecystectomies.[16] Reasons for incomplete resection include poor visualization of gallbladder fossa during surgery, adhesions, concurrent inflammation, excessive bleeding, or confounding gallbladder morphology such as a congenital duplication or an hour glass configuration due to adenomyomatosis.[9,17]

Diagnosis and management of retained calculi can be challenging. Most of the patients with retained calculi require surgical intervention. Our aim is to review the literature for residual gallbladder stones after cholecystectomy, discuss diagnosis and management strategies in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A protocol for a review of the literature was developed including search methods, literature review and criteria to select the studies assessed. The review used the Medline, Google and Cochrane library between 1993 and 2003. The following search terms were used: Residual gallbladder stones, post-cholecystectomy syndrome, retained gallbladder stones, gallbladder remnant, cystic duct remnant, subtotal cholecystectomy. Secondary searches of selected articles and reviews were performed. Full-text sources were available for most titles; however some data was derived from abstracts alone. The bibliographical references of each of these articles considered were also analyzed to find other articles that contributed to our review. The review included all the relevant publications in English language.

Two authors separately reviewed titles and abstracts obtained from search using a predefined data extraction form. Articles were retrieved when they seemed to potentially meet the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were then applied independently by both the authors to retrieved articles. Any differences were referred to a senior author for final analysis. There were no restrictions regarding the type of study or the characteristics of patients. The parameters that were assessed and analyzed include demographics, time of detection, clinical presentation, mode of diagnosis, nature of intervention, site of stone, surgical findings, procedure performed, complete stone clearance, sequelae and follow-up. Articles with insufficient data (on the site of residual gallbladder stones, mode of diagnosis), unclear methodology, published before 1993 and language other than English were excluded from the study.

RESULTS

A total of 83 articles published between 1993 and 2013 were found in the databases that we searched. Among these, 18 were selected for the study on the basis of our inclusion and exclusion criteria. After analyzing the bibiliographical references of these articles, we found some other articles that had been published in the same period. Out of these, four new articles were selected and included in our study. Therefore, a total of 22 published articles were used for the present study. Among these articles, 13 had been published as case reports and 9 as case series (observational studies). There were no randomized studies available in the literature on the subject.

Patient Demographics

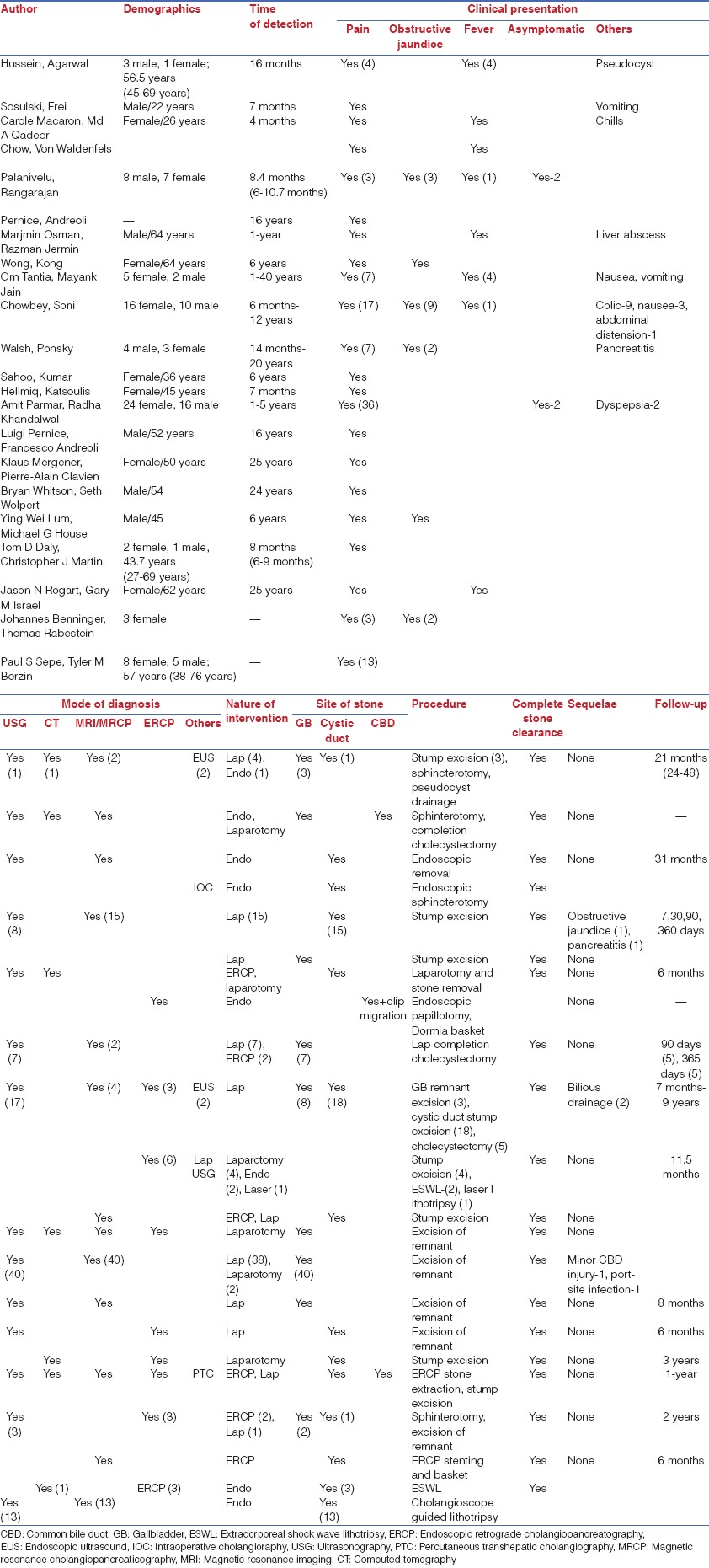

The patient demographics are stated in the accompanying table [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient demographics, clinical findings and nature of intervention

Clinical Presentation

The most common presentations were abdominal pain, fever and jaundice [Table 1]. Some of the rarer clinical presentations included pseudocysts, vomiting, chills, liver abscess and pancreatitis.

Chowbey et al. reported a mean time of detection of 4.1 years (range 6/12-12 years). Walsh et al. reported that the mean time interval between cholecystectomy and the diagnosis of retained calculi in a gallbladder/cystic duct remnant was 9.5 years (range 14 months to 20 years). Palanivelu et al. reported a mean time of detection of 8.3 months (range 6-10.7 months).

Walsh et al. reported that patients were referred to their institute with obscure persistent symptoms post-cholecystectomy. Tantia et al. in their series reported that all the patients were symptomatic for more than 3 months prior to revision cholecystectomy. Daly et al. in their case report mentioned recurrent biliary pain and obstructive jaundice as presenting symptoms in a patient 6 months after undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Also, two more patients presented with three episodes of typical biliary colic and cholangitis 8 months and 9 months after surgery respectively. Sepe et al. reported abdominal pain as a presenting symptom in all patients. In the case series by Palanivelu et al., the presenting symptoms were jaundice in 3 patients, abdominal pain in 7 patients, cholangitis (with fever, jaundice and pain) in 2 patients, pruritis associated with jaundice in 1 patient and aymptomatic in 2 patients. Chowbey et al. reported pain in the right hypochondrium (17 patients), recurrent biliary colics (9 patients) and jaundice (9 patients) as the most common presenting symptoms. Parmar et al. reported abdominal pain in 36 patients, persistent dyspepsia as the commonest presenting symptoms.

Mode of Diagnosis

In most series, the primary diagnosis was established by ultrasound/computed tomography (CT) scan. Subsequent localization of the calculi and delineation of the biliary tract was performed by magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In a few series the diagnosis was established by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), laparoscopic ultrasound, intraoperative cholangioraphy and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

Chowbey et al. in their series reported that the residual gallstones were diagnosed on abdominal ultrasound in 17 patients (includes 5 patients with primarycholecystostomy). The ultrasound reported 8 patients with a remnant gallbladder containing calculi. All other ultrasound reports mentioned an echogenic focus in the gallbladder fossa. The remaining 9 patients (7 patients post-LC and 2 patients post-open cholecystectomy) were diagnosed on EUS (2 patients), MRCP (4 patients) and ERCP (3 patients) respectively. In all 9 patients, a stone was reported in the residual cystic duct stump. Seventeen patients (65.3%) were subjected to a pre-operative ERCP.

Diagnosis was established by abdominal ultrasound, MRCP in the study by Parmar et al. Walsh et al. reported that all their patients received some form of biliary imaging for diagnosis: Six patients underwent ERC, one patient underwent MRCP. ERC correctly diagnosed the presence of a retained stone in the cystic duct or retained gallbladder in 4 patients. Biliary imaging was non-diagnostic in the remaining 3 patients. Daly et al. reported ERCP as the diagnostic modality in one patient which showed a dilated cystic duct (6 mm) with a stone present at the junction of the cystic duct with the common bile duct (CBD). In two more patients, ERCP conformed the diagnosis with a long cystic duct with a remnant of Hartmann's pouch and a filling defect inside in one patient and a stone in the CBD with 2 cm segment of residual gall bladder with dilated cystic duct in the other patient. Sepe et al. reported that all patients received biliary imaging in the form of MRCP, CT scan or ERCP. Palanivelu et al. reported that ultrasonography identified cystic duct remnant in 9 patients and MRCP identified calculus in all patients. Mahmud et al. reported that the ultrasound scan of the biliary tree was performed to establish the diagnosis.

Nature of Intervention

Nature of the intervention for residual gallstones that has been described in the literature includes Laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic techniques and open surgery. Laparoscopic surgery included remnant cystic duct stump excision and completion cholecystectomy along with drainage of the pseudocyst. Endoscopic management included endoscopic stone extraction, endoscopic pappilotomy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), laser lithotripsy and cholangioscope guided lithotripsy

Tantia et al. in their series of 7 patients reported that 2 patients had direct radiological evidence of CBD calculi along with a large stump without any calculus. ERC and stone extraction were attempted in both these patients who failed due to large calculus in CBD in one and multiple stones in other. These two patients underwent laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy along with laparoscopic CBD exploration. In the first patient CBD clearance was confirmed with intraoperative choledochoscopy and primary closure of CBD was performed with antegrade stenting. In the second patient after clearing the CBD, laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy was performed due to large stone load. The remaining five patients underwent laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy.

Chowbey et al. in their case series on laparoscopic management of residual gallstones reported that 26 patients underwent a revision or laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy for residual gallstones disease. Out of these, laparoscopic excision of gallbladder remnant was performed in three patients, and excision of cystic duct stump with stone was performed in 18 patients. A formal laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 5 patients who had previously undergone cholecystostomy and cholecystolithotomy. Parmar et al. reported that all 40 patients were managed by laparoscopic excision of gallbladder remnant, except for two patients who required conversion to open surgery. These two patients required conversion due to severe dense adhesions.

Walsh et al. reported in their series that the management was accomplished partly on the basis of how the definitive diagnosis had been obtained. Three patients who were diagnosed only at the time of surgery underwent resection of gallbladder remnant (one patient) and excision of retained cystic duct with calculi (two patients). Four patients had an ERC that accurately diagnosed a retained remnant or calculi. Two of these patients were treated surgically, one via completion laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the other via open excision of a retained cystic duct with impacted stones. Two patients underwent definitive endoscopic therapy: Both required fragmentation of cystic duct calculi which was achieved with ESWL in one and Holmium laser application in the other. The stone fragments were then swept from the cystic and common ducts with a balloon catheter.

Daly et al. in their case report of 3 patients reported that in one patient ERCP showed a dilated cystic duct (6 mm) with a stone present at the junction of the cystic duct with the CBD but the CBD was normal. The stone was unable to be retrieved endoscopically after a sphincterotomy was performed. A subsequent ERCP confirmed that the stone had passed. The second patient underwent ERCP. At ERCP, a long cystic duct was demonstrated with a remnant of Hartmann's pouch and a filling defect inside. A laparoscopic exploration was performed, and the gallbladder stump resected. The third patient underwent the sphincterotomy after the ERCP demonstrated a stone in CBD and 2 cm segment for residual gallbladder with dilated cystic duct. The stone was retrieved at sphincterotomy. Completion cholangiogram revealed no other stones.

Sepe et al. in their series on single operator cholangioscopy for extraction of cystic duct stones reported that 13 patients underwent 17 single operator cholangioscopy (Spyglass Direct visualization system, Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass, USA) for extraction of cystic duct stones. A single stone was present in the cystic duct in 9/13 patients, and at least 3 stones were present in 4/13 patients. In 7 patients, stones were noted to be in the distal cystic duct. Three patients had multiple stones in the remnant cystic duct. In 3 patients, the exact location of the stones could not be ascertained despite the review of cholangiogram and endoscopy images. The decision was made to go directly to a spyglass procedure in 3 patients rather than attempt a traditional approach given the large and multiple cystic duct stones. Twelve of 17 procedures were completed with patients under monitored anesthesia care, and 5/17 were performed under general anesthesia. Complete cystic duct clearance on the first attempt was achieved in 7/13 patients. One patient had partial extraction on the first attempt and had a repeat cholangioscopy 6 weeks later achieving complete cystic duct clearance. One patient had successful extraction of 3 cystic duct stones, but one stone dislodged into the CBD and could not be removed. A stent was placed, and ERCP was performed 6 weeks later with successful bile duct clearance. One patient had failed extraction and underwent a repeat spyglass procedure 3 months later in which the cystic duct was noted to be clear. Thus, complete clearance was achieved in 10 of 13 patients.

Palanivelu et al. reported that all 15 patients were successfully managed by laparoscopic excision of the remnant gallbladder/cystic duct. These patients had undergone laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy at the same center. The remnant cystic duct could be completely excised in 11 patients and CBD closed with intracorporeal suturing using 3.0 Vicryl. In the other 4 patients, closure after remnant excision could not be achieved and a T tube was inserted into the CBD via the cystic duct opening.

Site of Residual Gallbladder Stone

The residual gallbladder stones were retrieved from the gallbladder remnant in 64 patients, remnant cystic duct in 46 patients and in 3 patients from the CBD.

Follow-up

The mean follow-up from reported literature was 1.44 years (range 4 months-3.2 years). One patient developed obstructive jaundice. Two patients had pancreatitis and 2 patients reported bilious drainage in the post-operative period. A minor CBD injury and port site infection were reported in one patient each.

DISCUSSION

Persistence of symptoms after cholecystectomy may be due to retained stones or regeneration of stones in the remnant gallbladder.[18,19] This usually takes the form of right upper quadrant abdominal pain and dyspepsia, with or without jaundice. The causes of post-cholecystectomy syndrome are often non-biliary like peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux, pancreatic disorders, liver diseases, irritable bowel and coronary artery disease.[19] However, in some of these patients the cause may be biliary such as choledocholithiasis, traumatic biliary stricture, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or cystic duct/gallbladder remnant.[20,21] Patients with symptoms suggestive of gallstone disease such as biliary colic and obstructive jaundice justify a detailed evaluation to rule out any retained stone. The incidence of post-cholecystectomy syndrome has been reported to be as high as 40%, and the onset of symptoms may range from 2 days to 25 years.[18,22,23,24] There may also be gender-specific risk factors for developing symptoms after cholecystectomy. Bodvall and Overgaard found that the incidence of recurrent symptoms among female patients was 43%, compared to 28% among male patients.[25]

Several reports have proposed that a cystic duct remnant >1 cm in length after cholecystectomy may be responsible, at least in part, for post-cholecystectomy syndrome,[26,27] other authors refute this.[4,25] Residual gallstones are more often reported in cystic duct remnants. The possible etiology of such an occurrence is often a failure to define the cystic duct, CBD junction. This is more likely to occur in the presence of acute local inflammation or fibrosis. It may be prudent to dissect the cystic duct up to the common duct defining their junction in selected patients. Patients at increased risk of harboring stones in the cystic duct are patients with a history of biliary colics, pancreatitis, obstructive jaundice and those having undergone therapeutic ERCP prior to clipping and dividing the cystic duct. Stones in the cystic duct may be evident on visualization or may also be palpated with the dissector. Adhesions around the cystic duct may be another indicator of an impacted stone within it. In these circumstances, dissection should continue proximal to the stone towards junction of the cystic duct and CBD. With increasing experience, it is almost always possible to apply clips on the cystic duct proximal to the stone. No attempt should be made to ‘milk’ the stone distally, as such a maneuver may fragment the stone that may pass into the common duct and lead to biliary colic in the post-operative period.

Moody[19] included gallbladder remnant among the main causes of post-cholecystectomy syndromes; he cited Bodvall's previous experience concerning 26 cases of gallbladder remnant as a cause of post-cholecystectomy syndrome observed in a total of 103 cases operated on, equal to an incidence of 25%.[25] Stone recurrence in a gallbladder remnant after cholecystectomy, either laparotomic or laparoscopic, may arise alternatively from three different conditions: Inadvertent incomplete gallbladder removal, incorrectly performed subtotal intentional cholecystectomy (fundectomy alone), or ultimately the existence of a duplicated or even triplicated gallbladder inadvertently missed at the intervention (or probably voluntarily missed because seemingly healthy). Incomplete gallbladder removal during cholecystectomy may be both voluntary and inadvertent. Kuster and Domagk recommend a temporary laparoscopic cholecystostomy followed by delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy as an alternative to conversion to open cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis.[28] Similar recommendations have been duplicated by other authors wherein a tube cholecystostomy has been suggested to be a good salvage procedure in select patients with acute cholecystitis or a poor general condition.[29,30,31] Subtotal cholecystectomy has been recommended as a safe and viable option in patients where anatomical distortion at Calot's triangle precludes a safe dissection.[31,32,33,34,35] Conversion rate to open surgery is higher for patients with acute cholecystitis than in those without acute cholecystitis. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy has been suggested as an alternative to decrease this conversion rate.[35]

Recent progress in radiological imaging has greatly improved diagnostic accuracy in detecting the causes of persistence of symptoms in post-cholecystectomy patients.[1,36] Ultrasound, CT scan, ERCP, and MRCP are all effectively used to achieve a diagnosis of gallbladder remnant with or without stones in patients complaining of symptoms consistent with post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Nevertheless, diagnosis of residual gallbladder with gallstones remains difficult. An EUS is indicated in the presence of a high index of clinical suspicion with a negative abdominal ultrasound. EUS has proven its feasibility in diagnosing liver and biliary pathologies with a high sensitivity (96.2%) and specificity (88.9%) and has also been shown to be cost effective in avoiding a number of ERCPs.[37,38,39] ERCP is popular as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in managing extrahepatic biliary pathology. However, it is an invasive investigation and associated with a specific procedure related complications.[40] The main advantage of MRCP is its non-invasiveness, absence of sedation and avoidance of radiation exposure. Its sensitivity and specificity are similar to EUS.[39]

Treatment options depend on the suspected etiology. Once the patient has been diagnosed with residual stone, surgical excision should be undertaken to avoid potentially life-threatening complications, such as carcinoma, recurrent cholangitis, mucocele, recurrent cholelithiasis with gross dilatation of remnant, and Mirizzi syndrome.[23,41]

The first laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy was reported by Gurel et al. in 1995.[25] Traditionally, the open technique was considered as the procedure of choice for tackling these residual stones. Later, the laparoscopic approach became popular, though only attempted in advanced centres. After incomplete cholecystectomy, the cystic duct stump and Calot's triangle is usually embedded in inflamed scar tissue, so it was thought that the surgical risk was too high to reoperate laparoscopically in these cases. As in other surgical disciplines, minimally invasive surgery has revolutionised the management protocol of these patients, subject to availability of expertise. Many experts have successfully excised the cystic duct remnant laparoscopically, thus, leading to full recovery of the patient without significant post-operative morbidity. It has now been suggested that it is safe and feasible to remove the gallbladder or gallbladder remnants in such patients laparoscopically.[42] Despite some previously reported contrary opinions, the laparoscopic approach to reoperations on the biliary tract appears to be a minimally invasive, safe, feasible, and effective procedure when done by expert laparoscopic surgeons.[43]

Case reports of cystic duct calculi after cholecystectomy show mixed results about interventions using ERCP alone.[9,23,44,9] During the last two decades, cases have been reported in which cystic duct remnant stones were treated endoscopically, either percutaneously after surgical cholecystostomy or via a retrograde transpapillary approach.[45,46] Beyer et al. noted that it was easy to extract multiple stones from the cystic duct remnant in their patient, but Kodali and Petersen encountered marked problems in removing calculi from two patients with post-cholecystectomy Mirizzi syndrome. Non-surgical option like ESWL is also reported.[47] With evolving experience and the development of ancillary methods, such as ESWL, EHL (Electrohydraulic lithotripsy), and laser lithotripsy, it has become possible to treat patients with Mirizzi syndrome by using interventional endoscopic methods. ESWL, combined with appropriate therapeutic endoscopic interventions, is safe and effective for the treatment of cystic duct remnant stones and Mirizzi syndrome, especially when it is desirable to avoid surgical therapy

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim JY, Kim KW, Ahn CS, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Shin YM, et al. Spectrum of biliary and nonbiliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Radiologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:783–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyas FL, Nayak S, Perakath B, Pradhan NR. Gallbladder remnant and cystic duct stump calculus as a cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome. Trop Gastroenterol. 2005;26:159–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn F, McSherry CK. Secondary abdominal operations for symptoms following biliary tract surgery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;121:979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogy MA, Függer R, Herbst F, Schulz F. Reoperation after cholecystectomy. The role of the cystic duct stump. HPB Surg. 1991;4:129–34. doi: 10.1155/1991/57017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieger R, Wayand W. Gallbladder remnant after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:844. doi: 10.1007/BF00190098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackard WG, Jr, Baron TH. Leaking gallbladder remnant with cholelithiasis complicating laparoscopic cholecystectomy. South Med J. 1995;88:1166–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199511000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SA, Attiyeh FF, Kasmin FE, Siegel JH. Persistence of the gallbladder following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A case report. Endoscopy. 1995;27:334–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh RM, Chung RS, Grundfest-Broniatowski S. Incomplete excision of the gallbladder during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:67–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00187890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh RM, Ponsky JL, Dumot J. Retained gallbladder/cystic duct remnant calculi as a cause of postcholecystectomy pain. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:981–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly TD, Martin CJ, Cox MR. Residual gallbladder and cystic duct stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:375–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2002.02393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellmig S, Katsoulis S, Fölsch U. Symptomatic cholecystolithiasis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:347. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-4233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan H, Vilmann P. Insufficient cholecystectomy diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:236–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitson BA, Wolpert SI. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis in a retained gallbladder remnant after cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:814–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing J, Rochester J, Messer CK, Reiter BP, Korsten MA. A phantom gallbladder on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6274–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i46.6274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetriades H, Pramateftakis MG, Kanellos I, Angelopoulos S, Mantzoros I, Betsis D. Retained gallbladder remnant after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:276–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenfield NP, Azziz AS, Jung AJ, Yeh BM, Aslam R, Coakley FV. Imaging late complications of cholecystectomy. Clin Imaging. 2012;36:763–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beldi G, Glättli A. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for severe cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1437–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venu RP, Greene JE. Postcholecystectomy syndrome. In: Yamada T, editor. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lipincott; 1995. pp. 2265–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moody FG. Postcholecystectomy syndromes. Ann Surg. 1987;19:205–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schofer JM. Biliary causes of postcholecystectomy syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:406–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lum YW, House MG, Hayanga AJ, Schweitzer M. Postcholecystectomy syndrome in the laparoscopic era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:482–5. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou PH, Liu FL, Yao LQ, Qin XY. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:117–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mergener K, Clavien PA, Branch MS, Baillie J. A stone in a grossly dilated cystic duct stump: A rare cause of postcholecystectomy pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:229–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goenka MK, Kochhar R, Nagi B, Bhasin DK, Chowdhury A, Singh K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in postcholecystectomy syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1996;44:119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurel M, Sare M, Gurer S, et al. Laparoscopic removal of a gallbladder remnant. Surg Laprosc Endosc. 1995;5:410–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonson G, Nilsson DM, Nilsson T. Cystic duct remnants and biliary symptoms after cholecystectomy. A randomised comparison of two operative techniques. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopkins SF, Bivins BA, Griffen WO., Jr The problem of the cystic duct remnant. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;148:531–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuster GG, Domagk D. Laparoscopic cholecystostomy with delayed cholecystectomy as an alternative to conversion to open procedure. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:426–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00191631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradley KM, Dempsey DT. Laparoscopic tube cholecystostomy: Still useful in the management of complicated acute cholecystitis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12:187–91. doi: 10.1089/10926420260188083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berber E, Engle KL, String A, Garland AM, Chang G, Macho J, et al. Selective use of tube cholecystostomy with interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 2000;135:341–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji W, Li LT, Li JS. Role of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in the treatment of complicated cholecystitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:584–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philips JA, Lawes DA, Cook AJ, Arulampalam TH, Zaborsky A, Menzies D, et al. The use of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for complicated cholelithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1697–700. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michalowski K, Bornman PC, Krige JE, Gallagher PJ, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in patients with complicated acute cholecystitis or fibrosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:904–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinha I, Smith ML, Safranek P, Dehn T, Booth M. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy without cystic duct ligation. Br J Surg. 2008;95:534. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horiuchi A, Watanabe Y, Doi T, Sato K, Yukumi S, Yoshida M, et al. Delayed laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis with severe fibrotic adhesions. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2720–3. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9879-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terhaar OA, Abbas S, Thornton FJ, Duke D, O’Kelly P, Abdullah K, et al. Imaging patients with “post-cholecystectomy syndrome”: An algorithmic approach. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishra G, Conway JD. Endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of radiologic abnormalities of the liver and biliary tree. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:150–4. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheiman JM, Carlos RC, Barnett JL, Elta GH, Nostrant TT, Chey WD, et al. Can endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography replace ERCP in patients with suspected biliary disease? A prospective trial and cost analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2900–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filip M, Saftoiu A, Popescu C, Gheonea DI, Iordache S, Sandulescu L, et al. Postcholecystectomy syndrome — An algorithmic approach. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsubayashi H, Fukutomi A, Kanemoto H, Maeda A, Matsunaga K, Uesaka K, et al. Risk of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic biliary drainage. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:222–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enns R, Brown JA, Tiwari P, Amar J. Mirizzi's syndrome after cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:629. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chowbey PK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M. Laparoscopic reintervention for residual gallstone disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:31–5. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li LB, Cai XJ, Mou YP, Wei Q. Reoperation of biliary tract by laparoscopy: Experiences with 39 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3081–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw C, O’Hanlon DM, Fenlon HM, McEntee GP. Cystic duct remnant and the ‘post-cholecystectomy syndrome’. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beyer KL, Marshall JB, Metzler MH, Elwing TJ. Endoscopic management of retained cystic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:232–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kodali VP, Petersen BT. Endoscopic therapy of postcholecystectomy Mirizzi syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:86–90. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benninger J, Rabenstein T, Farnbacher M, Keppler J, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallstones in cystic duct remnants and Mirizzi syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]