Abstract

CONTEXT:

Mirizzi syndrome (MS), an unusual complication of gallstone disease is due to mechanical obstruction of the common hepatic duct and is associated with clinical presentation of obstructive jaundice. Pre-operative identification of this entity is difficult and surgical management constitutes a formidable challenge to the operating surgeon.

AIM:

To analyse the clinical presentation, pre-operative diagnostic strategies, operative management and outcome of patients operated for MS in a tertiary care centre.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This retrospective study identified patients operated for MS between January 2006 and August 2013 and recorded and analysed their pre-operative demographics, pre-operative diagnostic strategies, operative management, and outcome.

RESULTS:

A total of 20 patients was identified out of 1530 cholecystectomies performed during the study period giving an incidence of 1.4%. There were 11 males and 9 females with a mean age of 55.6 years. Abdomen pain and jaundice were predominant symptoms and alteration of liver function test was seen in 14 patients. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) the mainstay of diagnosis was diagnostic of MS in 72% of patients, while the rest were identified intra-operatively. The most common type of MS was Type II with an incidence of 40%. Cholecystectomy was completed by laparoscopy in 14 patients with a conversion rate of 30%. A choledochoplasty was sufficed in most of the patients and none required a hepaticojejunostomy. The laparoscopic cohort had a shorter length of hospital stay when compared to the entire group.

CONCLUSION:

MS, a rare complication of cholelithiasis is a formidable diagnostic and therapeutic challenge and pre-operative ERCP as a main diagnostic strategy enables the surgeon to identify and minimize bile duct injury. A choledochoplasty might be sufficient in the majority of the types of MS, while a laparoscopic approach is feasible and safe in most cases as well.

Keywords: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, laparoscopy, Mirizzi syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is an unusual complication of gallstone disease and occurs in approximately 1% of all patients with cholelithiasis.[1] The syndrome was first described in 1948 and is characterized by impaction of stones in the cystic duct or neck of the gallbladder (GB), resulting in mechanical obstruction of the common hepatic duct and frequent clinical presentation of intermittent or constant jaundice.[2] The majority of cases are not identified pre-operatively, despite the availability of modern imaging techniques. The purpose of this study is to analyse the pre-operative diagnostic methods, operative strategies and outcomes of surgical treatment in patients with MS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis that evaluated patients diagnosed with MS during the period from January 2006 to August 2013. The patient's demographic variables, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, diagnostic modalities, presence of choledocholithiasis, therapeutic procedures, post-operative complications, and follow-up period were evaluated. The Csendes classification was followed to categorize these patients based on pre-operative and intra-operative findings. All patients were seen in the surgical department within 3 months from their discharge from the hospital and every 6 months thereafter.

RESULTS

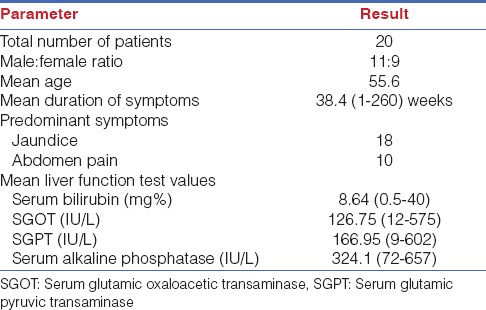

During this period, 1530 cholecystectomies were performed in our department, among which 20 patients were diagnosed with MS yielding an incidence of 1.4%. There were 11 males and 9 females with a mean age of 55.6 years (range: 27-74). Eighteen patients (90%) presented with abdominal pain, and 11 (55%) patients with jaundice, the mean duration of symptoms being 38.4 weeks (range: 1-260 weeks). Liver function tests were altered in 14 patients, the mean serum bilirubin of all patients was 8.64 mg/dl (0.5-40 mg/dl), and serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) values as shown in Table 1. Ultrasound abdomen the initial investigation of choice was diagnostic of MS in 40% of patients. Dilatation of intrahepatic biliary radicals, and proximal common bile duct (CBD), and non-visualized distal CBD, are features suggestive of MS. In addition computed tomography (CT) abdomen and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) done in very few patients was diagnostic in 33% and 100% of patients respectively. Endosonography was diagnostic of MS in 63% of patients and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) done in 18 patients was diagnostic in 72% of patients while the diagnosis was made intra-operatively in 8 out of the 20 patients in our series.

Table 1.

Patient demography and liver function test parameters

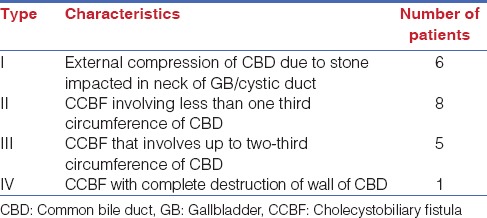

Cholecystectomy was initiated by laparoscopy in all 20 patients, it could be completed successfully by laparoscopy in 14 (70%) while the remaining 6 patients underwent conversion to laparotomy. Unclear anatomy of the Calot's triangle and uncontrollable bleed were the indications for conversion in four and two patients respectively. Based on intra-operative findings MS was classified according to Csendes et al. as Type I in seven patients, Type II in eight patients, Type III in four, and Type IV in one patient [Table 2]. During the surgery once a diagnosis of MS was made, after dissection of the GB, cystic duct close to the neck of GB was opened, and calculi were cleared from the cystic duct. The cystic duct opening was further extended on to the bile duct for a short length to ensure the stone clearance is complete. Visualisation of pre-operatively placed biliary stent if placed was taken as a guide for complete clearance and completion cholangiogram was used selectively to ensure stone clearance. After stone clearance Hartmann's pouch was amputated close to the CBD and the Hartmann's pouch was closed primarily with interrupted absorbable sutures in 11 patients and 4 patients underwent closure of Hartmann's over a catheter in the cystic duct. Although, two patients needed a T-tube insertion. No patient required a hepaticojejunostomy. One patient was diagnosed pre-operatively with a cholecystocolonic fistula, which required a laparotomy to deal with.

Table 2.

Csendes classification and incidence of different types of Mirizzi syndrome

The immediate post-operative course was uneventful in all except two patients. One patient had bile leak as evidenced by drain output, this was managed conservatively and the leak subsided over a period of 4 weeks. The intra-operative details and post-operative outcome are detailed in Table 3. The mean hospital stay was 5.4 days of the entire cohort, while the same was 4 days among the patients who underwent successful laparoscopy. The mean duration of follow-up was 47.3 (3-89) months. During follow-up, three patients were diagnosed with choledocholithiasis, one patient after 1 month, and the other two after 3 months, and all underwent ERC, and CBD clearance.

Table 3.

Intra-operative details and post-operative outcome

DISCUSSION

Mirizzi syndrome is a rare cause of obstructive jaundice produced by the impaction of a gallstone either in the cystic duct or in the GB, resulting in stenosis of the extra hepatic bile duct, and in severe cases, direct cholecystocholedochal fistula formation.[1] The reported incidence has ranged from 0.05% to 4% of all patients undergoing surgery for cholelithiasis.[2]

Its classification has evolved from Mc Sherry's original classification of two types to the four types as classified by Csendes [Table 2].[2,3] Clinical or pre-operative diagnosis is quite difficult. Pain is the most common presentation reported in 54-100% of patients, followed by jaundice in 24-100% of patients, which was also the case in our series.[3]

Biochemical parameters of liver function show a cholestatic pattern, simulating those of choledocholithiasis. Serum bilirubin ranges from normal to as high as 30 mg/dl with a mean of 7-10 mg/dl and serum ALP levels range from normal to about three- to ten-fold rise. Imaging studies are however the mainstay of pre-operative diagnosis.[4,5]

Ultrasound has a sensitivity of 23-46% in detecting MS, suggestive findings include a small contracted GB, containing a stone in the cystic duct, intrahepatic, and proximal extra hepatic ductal dilatation, calculus in the common duct, and normal-calibre or unprofiled distal common duct.[5] CT scan has a sensitivity similar to US, it may show a characteristic irregular cavity adjacent to the neck of GB containing the protruding stone, but can be helpful in diagnosing other causes of obstructive jaundice such as GB cancer, cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic tumour.[2] In our series, US did not provide details in any of our patients though CT scan done in two patients was diagnostic in one patient.

Pre-operative diagnosis is very important to avoid complications. Cholangiography remains the most reliable method of diagnosis of this syndrome, ERCP being the gold standard; the typical findings, include an excavating defect on the lateral wall of the CBD at the level of the cystic duct or GB neck, dilated common hepatic and intrahepatic ducts and normal calibre CBD. The advantage with ERCP is its additional therapeutic role in clearing concomitant bile duct stones and insertion of a biliary stent or nasobiliary catheter both of which may serve a temporising role and may help in intra-operative identification of the CBD.[2,6] ERC suggested the diagnosis in 13 out of 20 patients in our study, sphincterotomy and stent insertion was done in all of these patients. Magnetic resonance particularly T2-weighted images can detect all the diagnostic components of MS and can exclude malignancy on cross sectional imaging, while MRCP is equivalent to ERC in delineation of the ductal anatomy including the presence of fistula.[2,7]

Patients with MS constitute a formidable challenge and their surgical treatment a test to any surgeon's ability and dexterity because of the severe inflammatory process with thick, dense, hard adhesions and distortion of anatomy along with the presence of cholecystobiliary fistula. The dissection of Calot's triangle may lead to bile duct injury or excessive bleeding and other morbidity such as sepsis, delayed biliary stricture, and secondary biliary cirrhosis.[6,8]

Surgical management of MS includes careful dissection of the biliary structures, complete removal of stones from the biliary tract; and identification of the common hepatic duct. Intra-operative cholangiography should be performed whenever possible, especially in cases without definite pre-operative diagnosis or whenever MS is suspected during surgery. In the absence of cholecystobiliary fistula (Csendes Type 1), cholecystectomy and removal of the biliary stone constitutes the treatment of choice.[8,9]

A partial/subtotal cholecystectomy, with “fundus first” approach if necessary, is a safe alternative to exhaustive dissection of the cystic duct, and exposure of Calot's triangle, which risks opening of previously existent fistula or creation of a communication between the GB and the CBD. The GB is opened at the Hartmann's, and emptied of stones, the cystic duct is identified from inside the open GB seeking residual stones and is followed by secure suture closure of the cystic duct stump/Hartmann's. This procedure resulted in a successful outcome in 15 patients, while 4 patients underwent complete removal of the GB.

The surgical treatment of Types II and III is well defined, and the initial approach involves a subtotal cholecystectomy starting “fundus first” towards the Hartmann's pouch. Most of these types of cholecystobiliary fistula are diagnosed intra-operative, and it is necessary to leave a remnant GB of 5-10 mm around the fistula in order to aid closure of the bile duct and to avoid narrowing of the CBD. A T-tube may be placed in the CBD away from the fistulous site to prevent a future stricture or to worsen of the fistula. In the current series, T-tube drainage was required only in four patients as majority had an endoscopically placed stent or nasobiliary tube at the time of surgery. Most cases of MS Type II be successfully treated with this technique, though some cases, especially Type III with severe inflammation of GB might need a bilioenteric anastomosis.[1,6,9]

The treatment of Mirizzi Type IV with extensive destruction of the bile duct wall consists of a bilioenteric anastomosis. A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is the preferred and safer technique as it provides good long-term results with low morbidity and mortality rates.[1,6,9,10]

Mirizzi Syndrome in the Laparoscopic Era

The role of laparoscopic surgery in MS remains controversial and is considered technically challenging placing the patient at probably unnecessary increased risk of bile duct injuries.[11] Several authors have reported high conversion rates and procedure related complication and as a consequence recommended that laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be undertaken in select cases of Mirizzi Type I only, this based on the fact that a frozen Calot's triangle makes dissection hazardous at laparoscopy and unlike routine cases lateral traction on the infundibulum of GB does not open up the Calot's triangle.[4,6,10,11,12,13] A step by step approach to the laparoscopic management has been proposed by Rohatgi and Singh, highlighting the initial section of the GB fundus and retrieval of the impacted calculus to identify the infundibulum and cystic duct from thus facilitating a subtotal cholecystectomy.[14] However, the significance of a pre-operative diagnosis in lowering the risk of conversion and procedure related complications has also been highlighted by a few of the same authors.

In fact, in our series a pre-operative suspicion of MS at ERCP, along with the fact that these patients had a stent placed in the CBD before surgery enabled us to identify the CBD at surgery, and facilitated our dissection, thus lowering the risk of bile duct injuries. As suggested by Rohatgi and Singh our dissection concentrated on identifying the GB cystic duct junction and cystic duct CBD junction so that we were able to clear the impacted calculus from within and complete the cholecystectomy, while we resorted to a choledochotomy to retrieve the calculus from the cystic duct- CBD junction and the stent enabled us to achieve primary closure of the CBD in every case.[14,15] Chowbey et al. as early as 2000 had reported on a similar strategy and shown a good success rate with six conversions out of a total 22 cases in their series.[16] A similar successful combined endoscopic and laparoscopic approach has been published by Zheng et al., they stressed that these procedures should be performed by experienced hands.[17] A recent series by Li B et al. showed that a combined “tripartite” approach of pre-operative ERCP, laparoscopy, and intra-operative choledochoscopy is a safe and effective means of treating MS and is associated with faster post-operative recovery in terms of early resumption of oral feeds and shorter hospitalisation time.[18]

CONCLUSION

Mirizzi syndrome is a rare complication of long standing cholelithiasis that presents with features of choledocholithiasis. A pre-operative identification of the presence of MS helps in operative planning, and this is facilitated by ERCP, which enables the surgeon to identify the bile duct and achieve a primary closure of the bile duct. As shown in our series, closure of CBD with a cuff of GB can be safely done even in Types III and IV of MS with acceptable long tern outcomes. We also reiterate that a laparoscopic approach is feasible and safe in an otherwise difficult clinical problem and is associated with good short-term recovery.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mithani R, Schwesinger WH, Bingener J, Sirinek KR, Gross GW. The Mirizzi syndrome: Multidisciplinary management promotes optimal outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1022–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrarullah M, Mishra T, Das AP. Mirizzi syndrome. Indian J Surg. 2008;70:281–7. doi: 10.1007/s12262-008-0084-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: A unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139–43. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrarullah MD, Saxena R, Sikora SS, Kapoor VK, Saraswat VA, Kaushik SP. Mirizzi syndrome identification and management strategy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63:802–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1993.tb00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra MC, Vashishtha S, Tandon R. Biliobiliary fistula: Pre-operative diagnosis and management implications. Surgery. 1990;108:835–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltrán MA. Mirizzi syndrome: History, current knowledge and proposal of a simplified classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4639–50. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi BW, Kim MJ, Chung JJ, Chung JB, Yoo HS, Lee JT. Radiologic findings of Mirizzi syndrome with emphasis on MRI. Yonsei Med J. 2000;41:144–6. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2000.41.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corlette MB, Bismuth H. Biliobiliary fistula. A trap in the surgery of cholelithiasis. Arch Surg. 1975;110:377–83. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1975.01360100019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waisberg J, Corona A, de Abreu IW, Farah JF, Lupinacci RA, Goffi FS. Benign obstruction of the common hepatic duct (Mirizzi syndrome): Diagnosis and operative management. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:13–8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032005000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aydin U, Yazici P, Ozsan I, Ersõz G, Ozütemiz O, Zeytunlu M, et al. Surgical management of Mirizzi syndrome. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Makridis C. Laparoscopic treatment of Mirizzi syndrome: A systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:33–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui Y, Liu Y, Li Z, Zhao E, Zhang H, Cui N. Appraisal of diagnosis and surgical approach for Mirizzi syndrome. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:708–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon AH, Inui H. Pre-operative diagnosis and efficacy of laparoscopic procedures in the treatment of Mirizzi syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohatgi A, Singh KK. Mirizzi syndrome: Laparoscopic management by subtotal cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1477–81. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh K, Ohri A. Anatomic landmarks: Their usefulness in safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1754–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Mann V, Khullar R, Baijal M, Vashistha A. The management of Mirizzi syndrome in the laparoscopic era. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng M, Cai W, Qin M. Combined laparoscopic and endoscopic treatment for Mirizzi syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1099–105. doi: 10.5754/hge11069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Li X, Zhou WC, He MY, Meng WB, Zhang L, et al. Effect of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with laparoscopy and choledochoscopy on the treatment of Mirizzi syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3515–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]