Abstract

Background

Shared decision making (SDM) is considered a gold standard for the cooperation of doctor and patient. SDM improves patients’ overall satisfaction and their confidence in decisions that have been taken. The extent to which it might also positively affect patient-relevant, disease-related endpoints is a matter of debate.

Methods

We systematically searched the PubMed database and the Cochrane Library for publications on controlled intervention studies of SDM. The quality of the intervention and the risk of bias in each publication were assessed on the basis of pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The effects of SDM on patient-relevant, disease-related endpoints were compared, and effect sizes were calculated.

Results

We identified 22 trials that differed widely regarding the patient populations studied, the types of intervention performed, and the mode of implementation of SDM. In ten articles, 57% of the endpoints that were considered relevant were significantly improved by the SDM intervention compared to the control group. The median effect size (Cohen’s d) was 0.53 (0.14–1.49). In 12 trials, outcomes did not differ between the two groups. In all 22 studies identified, 39% of the relevant outcomes were significantly improved compared with the control groups.

Conclusion

The trials performed to date to addressing the effect of SDM on patient-relevant, disease-related endpoints are insufficient in both quantity and quality. Although just under half of the trials reviewed here indicated a positive effect, no final conclusion can be drawn. A consensus-based standardization of both SDM-promoting measures and appropriate clinical studies are needed.

The relationship between doctor and patient is continually changing under the influence of social and societal changes, among others (1). During the 20th century, improved access to information and patients’ desire for more autonomy contributed to a change in the relationship between doctor and patient from a mainly disease- and/or physician-orientated one towards dialogue and partnership. The bilateral exchange of information is now emphasized, and the patient plays a more active role in the treatment process. In Germany, this development is also reflected at the health political and legal levels—for example, in the so-called Patients’ Rights Act of 2013 (§ 630 of Germany’s civil code) and in the Medical Association’s Professional Code for Physicians in Germany. The latter states that patients’ consent to treatment should be obtained after patients were first given information on the treatment’s nature, importance, and consequences, including alternative treatments and associated risks. Increasingly, patients’ participation in decisions is also finding its way into treatment guidelines, for example in terms of recommendations on shared decision making (SDM) (2).

Active participation of patients in their treatment process can enhance clinical and psychosocial patient-related outcomes. Among others, a willingness and readiness to undertake initial treatment steps, trust in the medical decision, perception of risk, and realistic expectations can be fostered (3). Further relevant effects include increased satisfaction of patients and better adherence to treatment (4).

SDM is a crucial method in implementing patients’ education and participation. On the background of a partnership between doctor and patient, this is an interaction between both parties with the objective to use communication tools to reach a decision on an appropriate approach—for example, relating to treatment. Imparting current scientific evidence is a crucial component in this setting. The aim is to reach the best possible decision according to the clinical requirements and the patient’s preferences (3, 5). It needs to be borne in mind that the approach of patient participation is continually evolving. Depending on the respective perceptions of shared decision making, but also on the context, the implementation may differ (6– 8). Irrespective of this, SDM is a gold standard for the cooperation between doctor and patient (1). Studies have shown, however, that SDM has not yet comprehensively been adopted in clinical practice. Decisions about treatment are often still unilaterally made by doctors (9), although patients have a fundamental need to be involved in such decisions (10, 11).

Evidence for positive effects of increased patient participation in general has been delivered primarily for not directly disease-related outcomes (3, 4). The current state of research regarding the clinical relevance of SDM in particular is, however, not clear. A systematic review similar to our study investigated the effect on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes, but did not focus on SDM as a form of patient participation and limited the number of studies included to merely seven, on the basis of very strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (12). A detailed study from the Cochrane Collaboration focused primarily on the implementation of SDM as the study endpoint, but did not consider many of the outcomes and studies addressed by our own review (13). In our systematic review, we included controlled studies that explicitly investigated the effect of patient participation in the form of SDM on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a literature search with a cut-off date of 30 June 2014 in PubMed and the Cochrane Library, using the search terms “patient participation” and “decision making” and limiting the search to “clinical trial” as the publication type. We did not search for “shared decision making” as a medical subject heading (MeSH) term, since in our experience, some interventions are consistent with shared decision making but are not explicitly named as such.

Study selection and data extraction

KH and JM each applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed below to the search results. The inclusion criteria were:

A controlled study design

The explicit use of the terms “shared decision making” (SDM) or “participatory decision making” in the description of the intervention or information indicating that patients were involved in making a decision about treatment according to the first criterion of Charles et al. (Box) (14)

Fulfillment of at least one additional SDM criterion according to Charles et al. (14)

Assessment of patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes.

Box. Four criteria for shared decision making (14).

At least two parties (patient and doctor) are involved in the process.

They share information.

Both parties undertake steps to achieve a consensus regarding treatment preferences.

They agree on a form of treatment, which is then initiated.

The Charles criteria were applied in accordance with Joosten et al., among others (4). As patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes we considered parameters that were directly related to disease-dependent wellbeing or to a patient’s prognosis (Tables 1 and 2, eTables 1 and 2). We did not consider outcomes that related explicitly to the communication between doctor and patient—for example, the degree of informedness or satisfaction with the information—the doctor–patient relationship in general—such as the satisfaction of a patient with his/her doctor—or patient participation itself—for example, the number of questions asked by patients.

Table 1. Studies in which the interventions improved patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Underlying (main) diagnosis | Patient-relevant outcomes (measurement instruments)* |

|---|---|

| Status post acute coronary syndrome (23) | Proportion of patients with ≥ 3 risk factors; total cholesterol; LDL cholesterol; triglycerides; HDL cholesterol; systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure; body mass index; Proportion of patients who started treatment with statins during the study period; quality of life (SF-36) |

| Diabetes mellitus (24) | HbA1C; physical functioning (self-assessment); psychological functioning (self-assessment) |

| Diabetes mellitus (19) | HbA1C; physical limitations (RAND Medical History Index); intensity of therapeutic regimen; days of sickness absence from workplace |

| Ulceration (20) | Proportion of patients with role limitations; extent of role limitations; Proportion of patients with physical limitations; Extent of physical limitations; ulceration-related pain (9 questions) |

| Increased risk of breast cancer (BRCA1/2 mutation) (25) | Health status (self-assessment using 11-point scale); depression (CES-D); state anxiety (Spielberger STAI) |

| Breast cancer (17) | Generalized depression, specific depression (Leeds Anxiety and Depression Scale) |

| Substance-related addiction (21) | Severity of disorder (EuropASI): drug consumption, mental state; burden owing to addiction disorder (EuropASI) relating to alcohol consumption; physical status; legal problems; work and livelihood issues; proportion of abstinent patients; proportion of dependent patients; quality of life (EQ-5D) |

| Schizophrenia (22) | Reduction in social invalidity (GAF/WHO-DAS); Severity of symptoms, severity of illness (GAF/BPRS); inpatient stays (number and duration); psychotic episodes (number and duration); homelessness |

| Bronchial asthma (26) | Adherence (proportion of collected prescriptions); lung function (FEV1); use of medication as required; asthma control (ATAQ score); Quality of life (Mini AQLQ questionnaire) |

| Arterial hypertension (18) | Blood pressure lowering (systolic) in patients with a great need to participate; Adherence (number of medications taken) |

*bold: effects that reached significance in favor of the intervention compared with the control group.

AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale;

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EuropASI, European Addiction Severity Index; FEV 1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second;

GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; WHO-DAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

Table 2. Studies in which the interventions did not improve patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Underlying (main) diagnosis | Patient-relevant outcomes (measurement instruments) |

|---|---|

| Diverse (members of AOK and LKK Baden–Württemberg insurance schemes, receiving outpatient treatment) (27) | Physical quality of life (SF-12); psychological quality of life (SF-12) |

| Increased cardiovascular risk (28) | Estimated cardiovascular risk (Framingham score) |

| Fibromyalgia syndrome (36) | Intensity of pain (VAS); Depression (CES-D); general health (SF-36) |

| Prostate cancer (37) | Trait anxiety (Spielberger STAI); depressiveness/depression (CES-D) |

| Arterial hypertension (35) | Systolic blood pressure; cardiovascular risk (estimated on the basis of blood pressure, cholesterol, and HbA1C measurements); adherence (MARS-D) |

| Patients with increased cardiovascular risk (38) | Adherence (achieving self-defined targets for lifestyle modification); cholesterol concentrations |

| Antithrombotic treatment in atrial fibrillation (34) | Frequency of stroke or hemorrhagic events; proportion of patients taking warfarin; tendency to anxiety (Spielberger STAI) |

| Acute respiratory infection (32) | Adherence regarding original decisions in favor of or against antibiotic treatment; quality of life: physical and mental wellbeing (SF-12) |

| Depression (33) | Depressive symptoms (PHQ-D); adherence to treatment (self-assessment and doctor’s assessment on a 5-point scale) |

| Schizophrenia (31) | Medication adherence (doctors’ assessment, self-assessment); number of inpatient stays and admissions; proportion of patients who are still receiving psychiatric treatment |

| Schizophrenia (30) | Repeated inpatient admission within 8 months after discharge; medication adherence (MARS); global functioning (GAF); illness severity (CGI) |

| Atrial fibrillation, prostatic hyperplasia, menorrhagia, menopausal symptoms (29) | Illness-related tendency to anxiety and states of anxiety (Spielberger STAI); mental and psychological health (SF-12); adherence (yes/no-question) |

AOK, a large German general statutory health insurance fund; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression;

CME, continuing medical education; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; LKK, statutory health insurance for the agricultural sector; MARS, Medication Adherence Report Scale; PHQ,

Patient Health Questionnaire; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, visual analog scale

eTable 3. Statistical procedures used to calculate effect size d.

| Available data | Mean, x–standard deviation, s | t statistic, tor F statistic, F group or sample size, n 1 +n 2 = N | Significance level, pgroup or sample size, n 1 +n 2 = N | Chi square, χ ²group or sample size, n 1 +n 2 = N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula |  |

|

t = tinv(p; df) (Microsoft Excel) with Followed by calculation of d using t-statistic (see column 3)

|

|

| Source | (e2) | (e2) | (e3) | (e4) |

| Resource | (e5) | (e5) | Microsoft Excel | (e5) |

The statistical procedures used depended on the data available from the relevant publications

eTable 2b. Studies in which interventions did not improve adherence and patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Study | Underlying main disorderCase numbers = intervention group vs. control group at start/end of study | Measures in intervention group and control group | Patient-relevant outcomes*1 (measurement instruments)*2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (35) | Arterial hypertension n= 552/381 vs 568/357 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (38) | Patients with increased cardiovascular risk n = 322/266 vs 293/254 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (34) | Antithrombotic treatment in atrial fibrillation n = 53/51 vs 56/54 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (32) | Acute respiratory infection n = 216/181 vs 213/178 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (33) | Depression n = 283/191 vs 142/96 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (31) | Schizophrenia n = 32/32 vs 29/29 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (30) | Schizophrenia n = 35/30 vs 47/40 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (29) | Atrial fibrillation, prostatic hyperplasia, menorrhagia, menopausal symptoms n = 152/136 vs 201/186 |

Intervention group:

|

|

*1The p value of the group comparison is shown in parentheses.

*2Effect size as Cohen’s d

SDM, shared decision making; n. a., relevant data not available; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning;

MARS, Medication Adherence Report Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF, short form; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Our exclusion criteria were:

Use of a decision aid as the only difference between control group and intervention group.

Intended implementation of SDM in the control group too.

Lacking statistical data supporting the reported results.

After we had finished identifying suitable studies as described above, KH extracted the data. Only patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes were considered, as described in our inclusion criteria (15, e1).

Quality of publications and interventions

The methodological quality of the studies and the implementation of SDM interventions were assessed according to Joosten and colleagues (4). KH and JM individually evaluated the methodological quality of the included publications regarding the risk of bias. To this end, we adapted the Cochrane Back Review Group’s recommendations for systematic reviews (16) (eBox). Furthermore, we assessed the extent of SDM implementation on the basis of the number of identifiably applied key aspects according to Charles et al. as indicators of intervention quality (14) (Box). Since the literature does not provide a single definition of SDM, we adopted for our review the four Charles criteria—in accordance with Joosten et al.—which, in our view, can be considered a common denominator in interpretations of SDM (4, 8, 14).

eBox. Criteria for assessing methodological study quality according to Furlan et al. (16):

Was the study randomized?

Was the study adequately blinded?

Was the dropout rate/the proportion of subjects lost to follow-up 20% at most?

Were the outcomes in the groups under study measured at a comparable time?

Were the groups under study comparable regarding demographic characteristics and outcome-relevant parameters at baseline?

Were the results reported without bias and non-selectively?

Effect sizes

Where the publications provided sufficient data, we calculated the corresponding effect sizes as Cohen’s d, a measure of the relevance of statistically significant effects on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes (eTable 3) (e2– e5).

Results

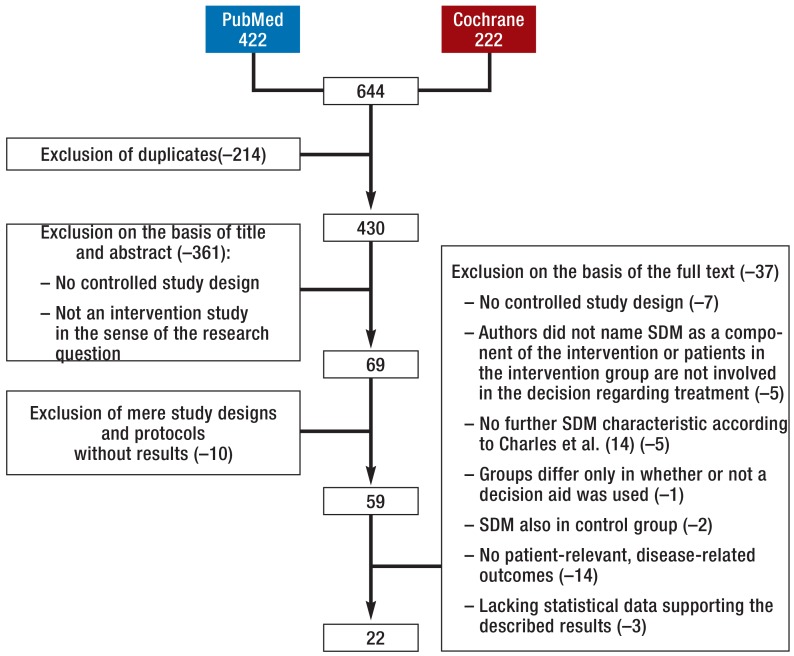

The search in PubMed yielded 422 hits and that in the Cochrane Library 222 hits. After removal of duplicates, we verified the remaining 430 publications on the basis of their title and abstract with regard to the research question and the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study protocols and designs without reporting concrete results were excluded. Of the 59 remaining articles, 37 were excluded after a review of their full text; ultimately, 22 controlled intervention studies were included in our review article (eFigure, Tables 1 and 2, eTables 1 and 2). We determined the risk for bias and found that the relevant information was often not fully reported. On average, 69% of the criteria were met. The proportion of lacking or unclear data relating to the criteria under study in the publications was 12%. It has to be kept in mind that we did not assess the quality of particular studies but that of the respective publications.

eFigure.

Systematic selection process of outcomes studies on shared decision making

SDM, shared decision making

In 10 of the 22 studies (45%), the intervention resulted in a significant improvement in at least one outcome compared with the control group (17– 26) (Table 1, eTable 1). In 12 of the studies (55%) this was not the case (27– 38) (Table 2, eTable 2). In the studies that showed benefits from the intervention, 57% of the relevant outcomes were significantly improved compared with the control group; this was the case for 39% when all 22 studies were considered. In studies that showed a benefit from SDM, the median effect size was 0.53 (range 0.14–1.49). Values were evenly distributed among ranges indicating small, moderate, and large effect sizes (eTable 1). We deemed individual outcomes in three studies not meaningful as significant differences existed between groups already at baseline. However, in one these three studies the positive effect on several other outcomes was greater than in the control group (23). In neither of the remaining two studies did any other relevant outcome show greater improvement in the intervention group compared to the control group (37, 38).

eTable 1a. Studies in which interventions improved patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Study | Underlying main disorderCase numbers = Intervention group vs. control group at start/end of study | Measures in intervention group and control group | Patient-relevant outcomes (measurement instruments)*1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (23) | Status post acute coronary syndromen = 72/67 vs. 72/69 | Intervention group:

|

After 12 months:

|

| (24) | Diabetes mellitus n = 30/23 vs. 31/29 |

Intervention group:

|

After 4 months:

|

| (19) | Diabetes mellitus (n = 39/33 vs. 34/26) |

Intervention group:

|

After 12 weeks:

|

| (20) | Ulceration (n = 23/22 vs. 22/22) |

Intervention group:

|

After 6–8 weeks:

|

| (25) | Increased risk for breast cancer (BRCA1/2 mutation) n = 44/42 vs. 44/40 |

Intervention group:

|

After 9 months:

|

| (17) | Breast cancer n = 36/13 vs. 35/10 |

Intervention group:

|

After 15 months:

|

| (21) | Addictionn = 111/79 vs. 105/87 |

Intervention group:

|

After 3 months:

|

| (22) | Schizophrenia n = 51/51 vs. 33/33 |

Intervention group:

|

After 24 months:

|

Numbers in bold print: significant effect in favor of intervention group

*1Effect size as Cohen’s d

*2Cohen’s d calculated on the basis of the adjusted mean value

n/a., effect size not available; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EuropASI, European Addiction Severity Index; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SDM, shared decision making; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SF, short form; WHO-DAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

eTable 2a. Studies in which interventions did not improve patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Study | Underlying main disorderCase numbers = intervention group vs. control group at start/end of study | Measures in intervention group and control group | Patient-relevant outcomes*1 (measurement instruments)*2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (27) | Diverse (members of AOK and LKK Baden–Württemberg insurance funds, receiving outpatient treatment) n = 496/309 vs. 911/408 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (28) | Cardiovascular risk n= 550/460 vs. 582/466 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (36) | Fibromyalgia syndrome n= 44/34 vs 41/33 |

Intervention group:

|

|

| (37) | Prostate cancer n= 30/n. a. vs 30/n. a. |

Intervention group:

|

|

*1The p value of the group comparison is shown in parentheses.

*2Effect size as Cohen’s d

n. a., relevant data not available; AOK, a large German general statutory health insurance fund; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CME, continuing medical education; LKK, statutory health insurance for the agricultural sector; SDM, shared decision making; SF, short form; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, visual analog scale

The studies were quite heterogeneous regarding disorders, outcomes, and interventions (Tables 1 and 2, eTables 1 and 2). The studies showing favorable results for SDM, as well as those where the effects in the control and intervention groups did not differ, included, among others, patients with cardiovascular disorders, respiratory disorders, mental disorders, or tumor disease. Examples of patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes addressed in the studies are disease-related surrogate parameters—for example, blood pressure—or psychological constructs (data obtained using patient questionnaires), as in depression or schizophrenia. The studied interventions ranged from brief conversations with patients that immediately preceded doctor–patient contact to several hours of staff training delivered over several weeks (eTables 1 and 2). In the studies showing benefit from SDM, patients were more often directly targeted by the intervention.

The extent to which SDM was implemented differed widely (Box). Twelve studies showed only one additional characteristic in addition to the participation of doctor and patient (17, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35– 38), five studies showed two further characteristics (19, 20, 24, 32, 34). All four SDM criteria were realized in five studies (23%) (18, 21, 26, 28, 30). No association was seen between outcome effects and the degree of SDM implementation (data not shown). The degree of SDM implementation might have been underestimated, as not all criteria were verifiable on the basis of the publications.

Discussion

In 12 of the 22 studies, the outcomes in patients who had received an SDM intervention did not show any greater improvement than the outcomes in patients of the respective control groups. Ten studies showed an advantage for SDM for patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes compared with the control groups. The observed effect sizes were high to very high in some cases.

The heterogeneity of diseases in the included studies does not allow for identification of disorders with a higher probability of SDM being beneficial. Similarly, we did not observe any association between the extent of SDM implementation and the outcome effect (data not shown). In the 10 studies that showed favorable results for SDM it is of note that most of the interventions (70%) directly aimed at the patient. In only three studies the intervention focused on doctors or nursing staff. Only 4 (33%) of the 12 studies in which the intervention showed no additional outcome benefit patients had been the primary target of the intervention. This finding suggests that an SDM intervention might improve patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes mainly if the intervention directly aims at the patient. Regarding SDM implementation as the outcome, Légaré et al. found that measures that involve doctors as well as patients are most effective (13).

Two studies in which treatment adherence was improved by the intervention to a greater extent than in the control groups showed an advantage for all outcomes that was deemed relevant for the present review (Table 1, eTable 1b). In 8 studies in which adherence was not improved as a result of the intervention, no significant outcome differences were seen (Table 2, eTable 2b). This finding suggests an association between adherence and improvements in patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes, similar to that we have recently found for antihypertensive treatment (5).

eTable 1b. Studies, in which interventions improved adherence and patient-relevant outcomes compared with control groups.

| Study | Underlying main disorderCase numbers = intervention group vs. control group at start/end of study | Measures in intervention group and control group | Patient-relevant outcomes (measurement instruments)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| (26) | Bronchial asthman = 204/182 vs 204/189 |

Intervention group:

|

After 12 months:

|

| (18) | Arterial hypertensionn = n. a./39 vs n. a./38–45 |

Intervention group:

|

After 12 months, only in intervention group:

|

Numbers in bold print: significant effect in favor of intervention group

*Effect size as Cohen’s d

AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; FEV 1, forced expiratory volume after 1 second; SDM, shared decision making; n. a., relevant data not available

The fact that about half of the analyzed studies did not show any positive effects as a result of an SDM intervention may have different reasons. As the methodological quality of many studies was limited, effects may have remained hidden. Two other reviews that differed from our approach in terms of their search strategies also stated that conclusive results regarding the effects of improved patient participation in general (12) and SDM in particular (8) on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes are lacking.

The quality of the implementation of SDM interventions was low to moderate in many studies. Twelve of the 22 studies included in our systematic review did not meet more than two Charles criteria. We did not find an association between the degree of SDM implementation and effects on the investigated outcomes (data not shown). However, considering the often insufficient information given in the publications, we cannot exclude that the aspects of SDM were not implemented intensely enough to reveal a corresponding effect. The problem of fitting the context—that is, the difficulty in finding the degree of SDM that meets the complex, context-specific needs of the individual patient—may also play a role (39).

It should also be considered that communication with and inclusion of patients in the control and intervention groups may not have differed sufficiently from one another. Thus, in studies where patients in the control group received so-called standard care, certain aspects of SDM may have been implemented more or less unintentionally. Of note, the literature does not provide an accepted consensus on the definition of SDM. Makoul and colleagues identified 31 different conceptual definitions (40). We and Josten et al. used SDM criteria originally defined by Charles et al. (4, 14), representing only one SDM concept that has been modified by the same group later (6).

As suggested above, it is likely that perceptions of SDM and thus the tested interventions may have differed in the studies included in our review. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria we applied probably did not cover every concept of SDM. This may mean that potentially relevant studies might have been missed.

In sum, we wish to remind readers that we assumed a study to show benefits for SDM if at least one outcome in the intervention group was improved to a greater extent than in the control group. The number of outcomes addressed in a study increases the risk of a cumulative α error, and thus the proportion of SDM interventions considered outcome-relevant may have been subject to overestimation.

Conclusion

We conclude that to date, research on the effect of SDM on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes is insufficient regarding the number of studies and the quality of relevant publications. Although nearly half of the identified studies indicated outcome-relevant effectiveness of SDM, the results so far do not allow for any conclusive assessment of the outcome relevance of SDM. A consensus-based standardization of SDM promoting measures and appropriate clinical studies are needed and desirable.

Key Messages.

If treatment adherence is enhanced, clinical outcomes can be improved.

Adherence to treatment can be optimized by patient participation in medical decision-making processes.

Shared decision making (SDM) is considered a gold standard in patient participation.

SDM can have a positive effect on patient-relevant, disease-related outcomes.

The studies available so far indicate a need for minimum standards regarding the implementation and investigation of shared decision making.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Albus has received consultancy fees as an advisory board member from UCB Pharma and lecture honoraria from Berlin-Chemie and Actelion.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Laidsaar-Powell RC, Bu S, McCaffery KJ. Partnering with and involving patients. In: Martin LR, DiMatteo RM, editors. The Oxford handbook of health communication, behavior change, and treatment adherence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 84–108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–1701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loh A SD, Kriston L, Härter M. Shared decision making in medicine. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104:A 1483–A1488. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219–226. doi: 10.1159/000126073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthes J, Albus C. Improving adherence with medication: a selective literature review based on the example of hypertension treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:41–47. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karnieli-Miller O, Eisikovits Z. Physician as partner or salesman? Shared decision-making in real-time encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullati S, Courvoisier DS, Charvet-Bérard AI, Perneger TV. Desire for autonomy in health care decisions: a general population survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders AR, van Weeghel I, Vogelaar M, et al. Effects of improved patient participation in primary care on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2013;30:365–378. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. CD003267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2009;34:1929–1941. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deadman JM, Leinster SJ, Owens RG, Dewey ME, Slade PD. Taking responsibility for cancer treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:669–677. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deinzer A, Babel H, Veelken R, Kohnen R, Schmieder RE. Shared decision-making with hypertensive patients. Results of an implementation in Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:2592–2596. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joosten EA, de Jong CA, de Weert-van Oene GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP. Shared decision-making reduces drug use and psychiatric severity in substance-dependent patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:245–253. doi: 10.1159/000219524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malm U, Ivarsson B, Allebeck P, Falloon IR. Integrated care in schizophrenia: a 2-year randomized controlled study of two community-based treatment programs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:415–423. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redfern J, Briffa T, Ellis E, Freedman SB. Choice of secondary prevention improves risk factors after acute coronary syndrome: 1-year follow-up of the CHOICE (Choice of Health Options In prevention of Cardiovascular Events) randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2009;95:468–475. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rost KM, Flavin KS, Cole K, McGill JB. Change in metabolic control and functional status after hospitalization. Impact of patient activation intervention in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:881–889. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.10.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Roosmalen MS, Stalmeier PF, Verhoef LC, et al. Randomized trial of a shared decision-making intervention consisting of trade-offs and individualized treatment information for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3293–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:566–577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzel LP, Vollmer M, Kriston L, Siegel A, Harter M. [Patient participation in medical decision making within an integrated health care system in Germany: results of a controlled cohort study] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:1524–1533. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1567-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krones T, Keller H, Sonnichsen A, et al. Absolute cardiovascular disease risk and shared decision making in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:218–227. doi: 10.1370/afm.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Involving patients in decision making and communicating risk: a longitudinal evaluation of doctors’ attitudes and confidence during a randomized trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, Busch R, Kissling W. Shared decision making and long-term outcome in schizophrenia treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:992–997. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamann J, Mendel R, Meier A, et al. “How to speak to your psychiatrist”: shared decision-making training for inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1218–1221. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legare F, Labrecque M, Cauchon M, Castel J, Turcotte S, Grimshaw J. Training family physicians in shared decision-making to reduce the overuse of antibiotics in acute respiratory infections: a cluster randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;184:E726–E734. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, Kriston L, Niebling W, Harter M. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson RG, Eccles MP, Steen IN, et al. A patient decision aid to support shared decision-making on anti-thrombotic treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation: randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:216–223. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinsel I, Buchholz A, Vach W, et al. Shared decision-making in antihypertensive therapy: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K, et al. Long-term effects of a shared decision-making intervention on physician-patient interaction and outcome in fibromyalgia. A qualitative and quantitative 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davison BJ, Degner LF. Empowerment of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:187–196. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koelewijn-van Loon MS, van der Weijden T, van Steenkiste B, et al. Involving patients in cardiovascular risk management with nurse-led clinics: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:E267–E274. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray E, Charles C, Gafni A. Shared decision-making in primary care: tailoring the Charles et al. model to fit the context of general practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Simplifying the language of evidence to improve patient care. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Rosenthal R. Parametric measures of effect size. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- e3.Higgins J, Green S. Green S, Higgins J, editors. Selecting studies and collecting data. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5. 1.0 updated March 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- e4.Rosenthal R, DiMatteo MR. Meta-analysis: recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:59–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Lenhard W, Lenhard A. Psychometrica – Institut für psychologische Diagnostik. www.psychometrica.de/effekstaerke.html. (last accessed on 20 January 2015) [Google Scholar]