Abstract

Objective

This study compared the effectiveness of an enhanced versus standard implementation strategy (Replicating Effective Programs-REP) on uptake of a national population management program (Re-Engage) for Veterans with serious mental illness.

Methods

Mental health providers at 158 VA facilities were given REP-based manuals/training in Re-Engage, which involved identifying Veterans who had not been seen in VA care for at least one year, documenting clinical status, and outreach to coordinate health care. After six months, facilities not responding to REP (n=88) were randomized to receive six months of facilitation (Enhanced REP) or continued standard REP. Site-level uptake was defined as percentage of patients with updated documentation or attempted contact.

Results

Rate of Re-Engage uptake was greater for Enhanced REP sites compared to standard REP sites (e.g., 41% vs. 31%;p=.01). Total REP facilitation time was 7.5 hours/site for six months.

Conclusions

Added facilitation improved short-term uptake of a national mental health program.

Keywords: mental disorders, implementation, care management, population health, population management, adaptive interventions

BACKGROUND

Persons with serious mental illness are disproportionately burdened by medical conditions (1) and homelessness (2) which can greatly increase risk for premature mortality (3). Two out of every five Veterans with serious mental illness experienced gaps in medical care lasting at least 12 months (4). Improving access to and continuity of health services may mitigate the health risks exacerbated by these gaps in care (3).

To address this disparity, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) tested the effectiveness of population management program (Re-Engage) in which Veterans with serious mental illness who had dropped out of care (i.e., not seen by a VA provider for at least one year) were identified and encouraged to return to care (5). Re-Engage consists of documentation of patients’ clinical status and outreach to assess need for healthcare (6) and was associated with a greater proportion of Veterans returning to VA care and six-fold reduction in mortality (5).

Subsequently, the VA approved a policy directive (7) in 2012 which authorized the national implementation of Re-Engage across VA facilities. VA program leadership wanted to ensure that Re-Engage was effectively implemented and sustained nationally by local providers, and had proactively sought to identify strategies to facilitate the uptake of this national program. Implementation intervention strategies, especially those that are theory-based and highly-specified are needed to help providers adopt core components of clinical interventions in routine care (8). However, standardized implementation strategies have not been widely tested for their effectiveness. Taking advantage of the VA's national implementation of Re-Engage, this study compared the effectiveness of a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to promote the uptake of Re-Engage among sites not initially responding to 6 months of the standard implementation strategy.

METHODS

This randomized controlled implementation intervention trial, described elsewhere (8), was reviewed and approved by the local VA Institutional Review Board. Sites not initially responding to an established implementation strategy (Replicating Effective Programs-REP) were randomized (9) at the VA regional network level to either continue the standard REP implementation intervention or, to receive an enhanced version of REP that included an external coach, or facilitator, to promote uptake of Re-Engage.

Re-Engage involved initial queries of VA national administrative databases to identify Veterans with a diagnosis of serious mental illness who had not been seen by a VA provider for at least a year, and required a mental health clinician to document Veterans’ clinical status, and attempt to contact and route them to appropriate VA health care when needed (5). The VA national Mental Health program generated an initial list of Veterans with either an inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 diagnosis for serious mental illness (schizophrenia-295.0-295.9 or bipolar disorder-296.0-296.1; 296.4-296.89) recorded between fiscal years (FY) 2008-2011 who were last seen at a VA facility in the 50 United States, who were still alive between FY2008-2011 based on U.S. death records, and as of FY11 had not received VA outpatient care for at least one year. The list was stratified by VA site where the patient was last seen and sent securely to a designated VA mental health clinician at that facility. These VA clinicians, known as local recovery coordinators, were identified by the VA national policy directive for the Re-Engage program to implement the Re-Engage program. As licensed independent practitioners (Master's level social workers or PhD psychologists), local recovery coordinators had the clinical expertise to implement the core components of the Re-Engage program, notably by updating the patient's clinical status in a web-based registry using available medical record data, information garnered from internet search engines or family members. Among patients still alive and who were non-institutionalized (e.g., not incarcerated or in nursing homes), local recovery coordinators were also able to attempt to contact the patient to assess the Veteran's current medical and psychosocial needs and schedule healthcare appointments if needed.

The primary focus of this study was to compare the two implementation strategies on the basis of improved uptake of Re-Engage (rather than on the improvements in patient-level outcomes due to the Re-Engage program itself. Therefore, the primary outcomes for this study were defined as the percentage of patients with an updated documentation of clinical status, and the percentage with an attempted contact by the provider. These measures represent core components of the Re-Engage program and were ascertained from the web-based registry (5, 8).

Between March and August 2012, local recovery coordinators at all VA facilities (n=158 sites) in the 50 United States were given the standard Replicating Effective Programs (REP) strategy, which included a toolkit, web-based registry link, training in the Re-Engage program via conference calls, and as-needed technical assistance to support implementation (8). After six months of standard REP, 42% (n=70) of sites had achieved minimum program implementation, which was defined as initial effort to update clinical status for >=80% patients in the web-based registry. Sites that did not achieve minimum implementation (58%;n=88) were then randomized, stratified by VA regional network level to receive Enhanced REP or continuation of standard REP.

Local recovery coordinators from sites randomized to Enhanced REP were assigned to one of three doctoral-level facilitators who provided coaching for 6 months. Providers from sites assigned to standard REP continued to have access to REP materials and could contact a separate technical assistant for Re-Engage program support, but did not receive coaching from facilitators. All personnel who operationalized and provided the Enhanced and standard REP implementation strategies, including facilitators and trainers, were located at a single site. Facilitators and trainers were partners with national VA Mental Health leadership and were not part of the Re-Engage providers’ local chain of supervision.

Enhanced REP facilitators provided coaching to local recovery coordinators on implementing Re-Engage at their site via semi-structured weekly calls (8). During the calls, facilitators assessed site-level barriers to Re-Engage uptake, reviewed progress, provided support and encouragement, and problem-solved action plans to overcome barriers to implementation. Facilitators also provided negotiation skills to help with securing time and resources from local leadership. The total time spent on facilitation activities was recorded using a weekly log form by each facilitator, including attempted and completed calls with providers, documentation, and weekly meetings with study investigators and VA national program leadership to review facilitation techniques and progress.

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the percentage of facilities achieving adequate Re-Engage uptake after 6 months based on the two measures (percentage of patients with a documentation of clinical status, and percentage with at least one attempted contact within 6 months). Repeated measures longitudinal analysis was used to compare site-level overall percentages between the standard versus Enhanced REP groups, adding the indicator for Enhanced (versus standard) REP, time (in months), the interaction of Enhanced REP by time, facility size (defined as overall number of unique patients at the site prior to site randomization), number of Veterans on the site's list for re-engagement, and whether the facility had an inpatient unit.

RESULTS

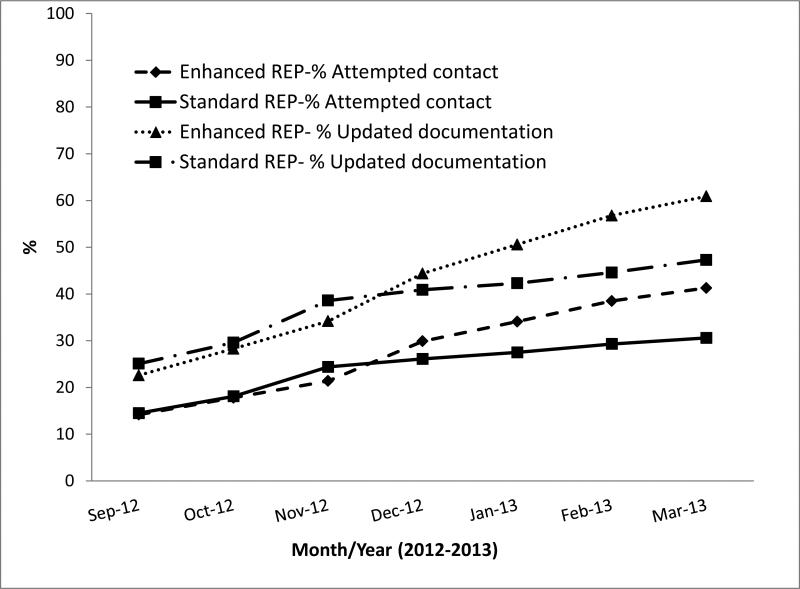

On September 1, 2012, 1,531 Veterans had been lost to care in the 88 VA sites not initially responding to 6 months of standard REP, with a median of 17 Veterans per site (range=4 to 44 Veterans). Six months later, sites receiving Enhanced REP compared to those receiving standard REP had a greater percentage of patients with an updated documentation of clinical status (61% vs. 47%; df=87;p=.01) and greater proportion of Veterans (N=579) with an attempted contact (41% vs. 31%; df=87; p=.01); Figure 1. Results from the repeated measures analysis indicated a greater rate of change among Enhanced REP compared to standard REP sites in percentage of patients with updated documentation (Enhanced REP by Time interaction Beta=.03;t=3.17;df=462; p<.001) and attempted contact (Enhanced REP by Time interaction Beta=.02; df=520;t=2.37; p=.01). The total amount of time all facilitators spent across the 39 sites during the six-month Enhanced REP period was 284.6 hours, or a total of 7.3 hours per VA site for a six-month “dose” of facilitation support. Limiting the analyses to sites with >=20 patients produced similar results (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Percent Updated Clinical Status, and Uptake in Attempted Patient Outreach Contact of the Re-Engage Program Between Sites Randomized to Receive Enhanced vs. Standard Replicating Effective Program (REP) Implementation Strategy, Among Sites Initially Not Responding to 6 months of Standard REP

DISCUSSION

In this implementation intervention trial, providers from sites randomized to receive added facilitation coaching compared to sites receiving standard toolkits, training, and as-needed technical support were more likely to implement a population management program for Veterans with serious mental illness that had dropped out of care. Few implementation strategies have been shown to improve the uptake of mental health programs, especially at the national level. Strategies like Enhanced REP are especially useful to large healthcare organizations that strive to roll out evidence-based programs to improve access to and outcomes for high-risk patients.

Assessing the effectiveness of Enhanced REP among sites not initially responding to standard REP was important as not all sites may need a more intensive implementation strategy to promote program uptake. This design also has the potential to inform the delivery of more cost-efficient implementation interventions (9).

There are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. The priority to conduct a national rollout of Re-Engage precluded more intensive monitoring of program uptake beyond documentation by frontline providers using the web-based registry, or having facilitators make in-person site visits. Generalizability of these findings may not extend beyond the VA or similar closed healthcare systems. The need to disseminate early findings on the effectiveness of facilitation to VA leadership mitigated the ability to wait for long-term patient-level outcomes data.

CONCLUSIONS

Added facilitation improves uptake of a national program among sites that are less responsive to standard implementation practices. These findings have the potential to inform not only the development of more cost-efficient implementation strategies but policies around national roll-out of programs (10). Further research is needed to determine the overall long-term impact and value of implementation strategies on improving the overall health of persons with mental disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (SDR 11-232). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA. The authors would like to acknowledge VHA Mental Health Services, VHA Mental Health Operations, and the VHA Office of the Medical Inspector for their support.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN21059161

The authors report no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, Haas GL, Salloum I, Conigliaro J, et al. General-medical conditions in older patients with serious mental illness. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:250–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Toole TP, Pirraglia PA, Dosa D, Bourgault C, Redihan S, O'Toole MB, et al. Building care systems to improve access for high-risk and vulnerable veteran populations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(Suppl 2):683–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1818-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Rosenheck RA, Miller AL. Unforeseen inpatient mortality among veterans with schizophrenia. Medical Care. 2006;44:110–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196973.99080.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy JF, Blow FC, Valenstein M, et al. Veterans Affairs Health System and mental health treatment retention among patients with serious mental illness: evaluating accessibility and availability barriers. Health Services Research. 2007;42:1042–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis CL, Kilbourne AM, Pierce JR, Langberg R, Blow FC, Winkel BM, et al. Reduced mortality among VA patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder lost to follow-up and engaged in active outreach to return to care. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:S74–S9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veterans Health Administration . VHA Directive 2012-002: Re-Engaging Veterans with Serious Mental Illness in Treatment. Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington, D.C.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilbourne AM, Abraham KM, Goodrich DE, Bowersox NW, Almirall D, Lai Z, et al. Cluster randomized adaptive implementation trial comparing standard versus enhanced implementation intervention to improve uptake of an effective re-engagement program for patients with serious mental illness. Implementation Science. 2013;8:136. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viggiano T, Pincus HA, Crystal S. Care transition interventions in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2012;25:551–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328358df75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almirall D, Compton SN, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Duan N, Murphy SA. Designing a pilot sequential multiple assignment randomized trial for developing an adaptive treatment strategy. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31:1887–902. doi: 10.1002/sim.4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Health Homes for Enrollees with Chronic Conditions. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; Baltimore, MD: Nov 16, 2010. [2013 October 21]. Available from: http://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/SMDL/downloads/SMD10024.pdf. [Google Scholar]