Abstract

The current study tested whether young adult’s recollected reports of their mother’s punitive reactions to their negative emotions in childhood predicted anger expression in young adulthood and whether emotional closeness weakens this association. Further, a three-way interaction was tested to examine whether emotional closeness is a stronger protective factor for young women than for young men. Results revealed a significant three-way interaction (gender X emotional closeness X maternal punitive reactions). For young men, maternal punitive reactions to negative emotions were directly associated with increased anger expressions. Maternal punitive reactions to young women’s negative emotions in childhood were associated with increased anger in adulthood only when they reported low maternal emotional closeness. Findings suggest that maternal emotional closeness may serve as a buffer against the negative effects of maternal punitive reactions for women’s anger expression in young adulthood.

Keywords: Emotional closeness, Emotion socialization, punitive reactions, trait anger, young adult

Introduction

Expectations regarding the expression of emotion are influenced by societal and cultural norms (Saarni, 1993), and there are rigid social expectations regarding the extent to which the expression of negative emotions such as anger is appropriate (Cole, Tamang, & Shrestha, 2006). People vary in the degree and frequency with which they experience and express anger over time, and individuals who tend to respond to situations with inappropriate hostility, have a tendency to perceive situations as more frustrating, and are more easily provoked, are thought to be high in trait-like anger (Deffenbacher et al., 1996; Spielberger, Jacobs, Russell, & Crane, 1983; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2007; Wilkowski, Robinson, Gordon, & Troop-Gordon, 2007). In addition to experiencing anger more often, persons with higher levels of trait anger are thought to experience anger more intensely (Spielberger et al., 1983). Thus, it is not surprising that higher trait anger has been linked to negative outcomes such as workplace aggression (Hershcovis et al., 2007), physical assault in dating relationships (Parrott & Zeichner, 2003), diminished physical health (Schum, Jorgensen, Verhaeghen, Sauro, & Thibodeau, 2003), and poorer mental health (Kopper & Epperson, 1996).

One predictor of children’s ability to appropriately express and regulate anger in childhood is parents’ emotion socialization of negative emotion (Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon, & Cohen, 2009; Perry, Calkins, Nelson, Leerkes, & Marcovitch, 2012). Therefore, the current study aimed to extend the emotion socialization literature and test whether young adults’ recollected reports of their mothers’ punitive reactions to their negative emotions in childhood predict trait anger in young adulthood, as well as examine whether maternal emotional closeness and gender may influence this association.

Emotion Socialization

How parents respond to children’s experiences of negative emotion such as anger, fear, anxiety, and sadness is an important aspect of emotion socialization and has been found to be associated with poorer social and emotional outcomes for children (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996; Jones, Eisenberg, Fabes, & MacKinnon, 2002). Researchers have suggested that negative responses such as the punishment of negative emotion may be particularly detrimental to children’s socioemotional functioning because these parental reactions communicate nonacceptance of negative emotional displays and focus on reducing the expression of negative emotion. In addition, responding punitively does not provide children with the problem solving skills and emotional support necessary for appropriately and effectively coping with negative emotional experiences (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Jones et al., 2002).

Empirical work has supported the association between parents’ punitive reactions to children’s negative emotions and children’s social and emotional outcomes. For example, in a sample of 4 to 6 year-olds, Eisenberg and Fabes (1994) found that maternal punitive responses were associated with children’s lower attentional control and higher negative affect. Similarly, Eisenberg et al. (1999) examined longitudinal relations between parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions and children’s social behavior and negative emotionality from early childhood to adolescence. Results revealed that children’s problem behaviors and compromised ability to regulate negative emotion were predicted by earlier parental punitive reactions; therefore suggesting that early punitive reactions have lasting effects into the adolescent years.

Although the association between punitive parental reactions to children’s negative emotions and social and emotional development has been established in early childhood and adolescence, little research has assessed the influence of negative parental reactions to children’s negative emotions on socioemotional outcomes into adulthood. Malatesta-Magai and others (Gergely & Watson, 1999; Malatesta, 1990; Malatesta-Magai, 1991) have posited that particular emotional states become increasingly reinforced and internalized as part of the self during social interactions with parents. Over an extended period of time, these patterns are thought to become more concrete and contribute to personality characteristics. Because emotion socialization behaviors aim to teach and reinforce parents’ beliefs and expectations regarding the appropriate display of emotion, emotion socialization during childhood is particularly likely to contribute to the development of these personal attributes over time. Thus, a better understanding of the lasting effects of parents’ emotion socialization of negative emotion on their children’s adaptive functioning can be gained by assessing its influence on socioemotional competencies and trait characteristics during emerging adulthood.

The lack of research assessing the influence of non-supportive parental reactions to children’s negative emotions on socioemotional outcomes beyond adolescence is likely due to the scarcity of longitudinal data that extends from early childhood to adulthood. Given this methodological constraint, one way to try to understand the relation between parents’ emotion socialization in childhood and outcomes in adulthood is to examine young adults’ recollected accounts of their parents’ emotion socialization practices. The validity of retrospective measures has been previously questioned (e.g., Widom & Shepard, 1996) because memories may be selectively recalled, distorted, forgotten, or shaped by later experiences (Hilton, Harris, & Rice, 1998; Tajima, Herrrenkohl, Huang, & Whitney, 2004). However, previous research has shown that adults’ recollected reports of parenting on other measures correlate with both their parents’ own self-reports of parenting and their sibling’s reports of parenting (e.g., Harlaar et al., 2008). Therefore, measuring adults’ retrospective accounts of their parents’ punitive reactions to their negative emotion may provide a preliminary understanding regarding the influence of early negative emotion socialization practices on young adults’ adaptive functioning.

Previous research has indicated that participants’ recollected reports of their parents’ negative responses to their negative emotions were associated with chronic emotional inhibition in adulthood; this inhibition was found to be subsequently associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Krause, Mendelson, & Lynch, 2003). Similarly, Garside and Klimes-Dougan (2002) found young adults’ recollected accounts of their parents’ punishing and neglecting responses to their negative emotions in childhood to be associated with higher levels of general psychological distress in adulthood. Taken together, these studies support the association between parental negative reactions to negative emotions in childhood and decreased mental health in adulthood, but whether parental emotion socialization of negative emotion has specific and lasting effects on the outward expression of emotion in adulthood is less understood.

Emotional Closeness

From a systems perspective, the influence of a behavior on an outcome cannot be isolated from the context in which the behavior occurs (White & Kline, 2008). However, researchers often do not adhere to a systems perspective and commonly measure mothers’ affective styles or behaviors without examining the emotional climate of the mother-child relationship (Wentzel & Feldman, 1996). There is support to suggest that parental behavior and perceptions of closeness are two distinct variables associated with adaptive functioning (Amato, 1989; Henry, Robinson, Neal, & Huey, 2006; Houltberg, Henry, & Morris, 2012). Thus, it may be that qualities of the relationship and parenting behavior each play a role in the development of socioemotional competencies.

A strong emotional connection between parents and their children has been found to be related to positive developmental outcomes such as increased mental health, adaptability, psychosocial maturity, healthy romantic relationships, and behavioral restraint in adolescence and young adulthood (Adams, Bersonsky, & Keating, 2006; Mullis, Brailsford, & Mullis, 2003; Owens et al., 1996; Reinherz, Paradis, Giaconia, Stashwick, & Fitzmaurice, 2003; Wentzel & Feldman, 1996). Further, familial relationships characterized by a stronger emotional connection are considered to be important contexts for assessing and understanding the relation between parenting behavior and children’s socioemotional development. Within the physical discipline literature, Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997) found a positive association between parent’s use of harsh discipline at 5 years-old and children’s behavior problems from kindergarten through sixth grade. However, this effect was considerably lower among families characterized by high levels of parental warmth and positive affect. McLoyd and Smith (2002) found a similar positive association between spanking and behavior problems over time in the context of low maternal emotional support. It is possible that emotional closeness serves a similar role in the relation between punishment of negative emotion and adaptive functioning.

Emotion socialization practices take place within familial contexts that are diverse with regard to general parenting styles and family functioning, and empirical work has not addressed the way in which relationship factors such as emotional closeness may impact the association between emotion socialization to children’s negative emotions and adult social and emotional outcomes. Emotional closeness has been associated positively with parents’ general praise, support, and supervision (e.g., Houltberg, Henry, & Morris, 2012), and children may develop a sense of closeness based on these parenting behaviors. It is possible that the sense of emotional closeness that develops from positive parenting more generally buffers children from potential negative effects of punitive reactions to their negative emotion on the development of trait anger into young adulthood. Said differently, although parents may utilize punishment as a means to discourage the expression of negative emotion during childhood, a close emotional bond that has developed within the parent-child relationship may make children less likely to internalize punitive emotion socialization behaviors and attribute them to their own self-worth or competencies, thus reducing the impact of punitive behaviors on negative outcomes in adulthood such as inappropriate anger expression.

Gender

Parents have been found to socialize their children’s negative emotions differently depending on the gender of the child. Specifically, parents discuss emotions with their daughters more than with their sons and are more likely to discourage anger and aggression in their daughters (Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005; Klimes-Dougan& Zeman., 2007). In addition, the relation between emotional closeness and socioemotional outcomes in young adulthood may be different for men and women. For instance, a close emotional connection may be particularly important for women, who tend to place more value on interpersonal relationships than men (Ryan, La Guardia, Solky-Butzel, Chirkov, & Kim, 2005). In an empirical study, Wentzel and Feldman (1996) found low levels of closeness in mother-daughter dyads to be related to adolescent girls’ depressive affect, low social self-concept, and lower levels of self-restraint. For adolescent boys, mother-son closeness was only related to increased social self-concept. Taken together, these findings suggest that it is important to examine the way in which gender may influence the association between emotional closeness and emotion socialization to negative emotion as it relates to adaptive socioemotional functioning.

The Current Study

The current study examined whether emotional closeness moderates the association between young adults’ recollected accounts of their mother’s punitive reactions to their negative emotions and their adult anger expression. It was hypothesized that emotional closeness would serve as a buffer against the negative effects of parental punitive reactions in childhood on anger expression in adulthood. Finally, men and women’s emotions are socialized differently (Klimes-Dougan & Zeman, 2007) and a close emotional connection may be more salient for women than men. Thus, a three-way interaction was tested to assess whether the moderating effect of emotional closeness operated similarly for both sexes. It was hypothesized that buffering effect of emotional closeness would be stronger for women than for men.

Methods

Participants

The participants in the current study were drawn from a larger sample of 686 students (72% female) ranging in age from 17 to 53 years-old (M = 20.51). Given the aims of this paper, the sample was restricted to include only young adults 25 years-old and younger. The current sample consisted of 641 undergraduates (177 males) attending a 4-year university in the southeastern United States. Participants ranged from 17 to 25 years-old (M = 19.63), and were European American (57%), African American (30%), Asian (4%), Hispanic (4%), and bi-racial (2%). Only 3% of the sample identified their race as something other than what was listed on the questionnaire. Freshman (40%), sophomores (31%), juniors (18%), and seniors (11%) participated, and most reported on their biological mother (97%).

Procedures

Researchers attended classrooms and the university cafeteria to recruit participants during the spring of 2012. Consent forms were summarized by a research assistant and every participant was given a copy to read and sign before participation. Upon signing the consent form, participants completed questionnaires regarding how they were parented during their childhood, their current relationship with their mothers, and current information about themselves. For their participation, participants were entered into a drawing for a Visa gift card.

Measures

Punitive Reactions

The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale-Revised (CCNES-R) was used to measure participant’s retrospective accounts regarding the degree to which participants reported that their mothers reacted punitively and decreased their exposure or ability to deal with their negative emotions. The CCNES-R was adapted from the original Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (Fabes, R.A., Eisenberg, N. & Bernzweig, J.; 1990). In the CCNES-R adult children are provided with 6 childhood scenarios in which they themselves experienced a negative emotion (e.g., angry or sad). Participants are asked to think back to their childhood and indicate the likelihood that their mother would have responded in a punitive way for each vignette. The 6 scenarios were identical to ones presented in the original CCNES and were re-worded to reflect the recollected nature of the question. Each response is rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (highly likely) and a mean score was created across the 6 scenarios. The items used to create the punitive reactions variable had internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of .62.

Emotional closeness

The Subjective Closeness Index (SCI; Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989) was used in the current study two assess young adults’ perceptions of closeness to their mothers with two questions. The first question asked, “Relative to all your other relationships (friends, siblings, etc.), how close is your relationship with your mother?” The second question asked, “Relative to what you know about other peoples’ relationships with their mothers, how close is your relationship with your mother?” Each response is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not close at all) to 5 (very close). The observed scores ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 and correlated (Pearsons r) at .83. The mean of both questions was computed and used as the emotional closeness variable in the current study. This measure has been found to be associated with expressive and cognitive indices of emotional closeness (Aron & Fraley, 1999; Berscheid et al., 1989), and correlated with other emotional closeness measures such as the Relationship Closeness Inventory (RCI; Berscheid et al., 1989) and the Inclusion of Other in the Self scale (IOS; Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1992).

Trait Anger

To assess trait anger, participants completed the 10 item trait anger subscale of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (Spielberger, 1988). Participants rated how frequently they tend to feel and express anger on 4-point scale ranging from almost never to almost always. Example items are “When I get mad, I say nasty things” and “I have a fiery temper.” Items were averaged such that higher scores indicate greater trait anger. Internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was .86.

Covariates

Young adults provided demographic information at each visit including age, academic level, gender, and race. In addition, participants completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES–D; Radloff, 1977) which consists of a checklist of moods, feelings, and cognitions associated with depression (e.g., “I felt depressed,” “I felt that people dislike me”) designed for use with community samples. Respondents indicated how often they felt a particular way during the previous week on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (rarely/never) to 4 (most of the time). In this sample, internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was .87.

Results

Because less than 5% of data was missing overall, single imputation using SPSS v. 20 was implemented. When implementing single imputation, an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm is used to replace missing data with a probable value based on other available information. Predictor variables, dependent variables, and demographics were included in the imputation model to maintain unbiased associations between the variables of interest (Sterne et al., 2009). Given the age range in our sample, as well as previous research that has indicated racial differences in emotion socialization behaviors (Nelson, Leerkes, O’Brien, Calkins, & Marcovitch, 2012), age, academic level, and race were included in all analyses as covariates. Further, because our measure of parental punitive reactions is recollected and individuals may recall events more negatively if they are depressed or are experiencing depressive symptoms, participants’ current depression was also entered as a covariate. Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables were analyzed. The means of emotional closeness and trait anger were not significantly different between young women (M = 4.21, SD = .90; M = 1.90, SD = .60) and young men (M = 4.14; SD = .97; M = 1.93; SD = .61). However, men (M = 3.35, SD = 1.12) did report that their mothers used more punitive reactions than women (M = 3.02, SD = 1.00), t(639) = −3.618, p < .01. Correlations among study variables and controls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations among Demographic Variables and Primary Study Variables (N = 641)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||

| 2. Academic level | .77** | – | ||||||

| 3. Race | .07 | .02 | – | |||||

| 4. Gender | .25** | .20** | −.04 | – | ||||

| 5. Depressive symptoms | −.03 | −.04 | −.02 | −.02 | – | |||

| 6. Emotional closeness | .00 | .01 | −.09* | −.04 | −.18** | – | ||

| 7. Recollected punitive reactions | .04 | .01 | .06 | .14** | .18** | −.16** | – | |

| 8. Trait anger | −.08 | −.08* | .01 | .02 | .28** | −.16** | .13** | – |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Race was coded (1 = nonwhite, 2 = white); gender was coded (1 = male, 0 = female).

Hierarchical multiple regressions were used to test whether emotional closeness interacted with retrospective accounts of mothers’ punitive reactions to predict trait anger differently for men and women in adulthood. This method assess whether adding the interaction term to the model explains a significant amount of the variance in young adults’ trait anger. All interaction effects were calculated using centered emotional closeness and punitive reaction variables. The regressions were computed as follows: To control for age, academic level, race, and depression, these variables were entered in the first block. Gender, Emotional Closeness, and Punitive Reactions were entered in the second block, and the two-way interactions of Emotional Closeness X Gender, Punitive Reactions X Gender, and Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions were entered in the third block. The three-way interaction term of Gender X Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions was entered in the fourth block. Results revealed a significant three-way interaction (see Table 2) indicating that young men and women differed in the way in which emotional closeness and maternal punitive reactions to negative emotions predicted trait anger.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions of Adult Trait Anger

| Gender x Emotional Closeness x

Punitive Reactions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | B (SE) | R2 | ||

|

|

||||

| Age | −.03 | −.01(.02) | ||

| Academic Level | −.07 | −.04(.04) | ||

| Race | .01 | .01(.05) | ||

| Depression | .23** | .01(.00) | ||

| Gender | .06 | .08(.06) | ||

| Punitive Reactions | .08 | .05(.03) | ||

| Emotional Closeness | −.01 | −.01(.03) | ||

| Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions | −.14* | −.06(.03) | ||

| Gender X Emotional Closeness | −.07 | −.09(.06) | ||

| Gender X Punitive Reactions | .05 | .05(.05) | ||

| Gender X Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions | .13* | .10(.05) | .11* | |

| Emotional Closeness x Punitive

Reactions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||

| β | B(SE) | ΔR2 | β | B(SE) | ΔR2 | |

|

|

||||||

| Age | .01 | .00(.04) | −.07 | −.03(.03) | ||

| Academic Level | −.09 | −.05(.06) | −.05 | −.03(.05) | ||

| Race | .09 | .10(.10) | −.02 | −.03(.06) | ||

| Depression | .37** | .02(.01) | .17 | .01(.00) | ||

| Punitive Reactions | .16* | .09(.05) | .09 | .05(.03) | ||

| Emotional Closeness | −.11 | −.08(.06) | −.01 | −.01(.03) | ||

| Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions | .10 | .05(.04) | −.13* | −.06(.03) | .02* | |

Note: N = 641

p<.05.,

p<.01.

In order to probe the three-way interaction, the data file was split by gender and separate regression models testing the interaction between emotional closeness and punitive reactions were conducted for men and women. Age, race, academic level, and depression were entered into the first block, emotional closeness, and punitive reactions were entered into the second block, and Emotional Closeness X Punitive Reactions was entered into the third block. The two-way interaction between emotional closeness and mothers’ punitive reactions was not significant for men (see Table 2). However, retrospective accounts of their mother’s punitive reactions to their negative emotions predicted men’s trait anger in adulthood as a main effect. That is, regardless of whether young men reported being close with their mother, greater maternal punitive reactions during childhood was associated with more trait anger.

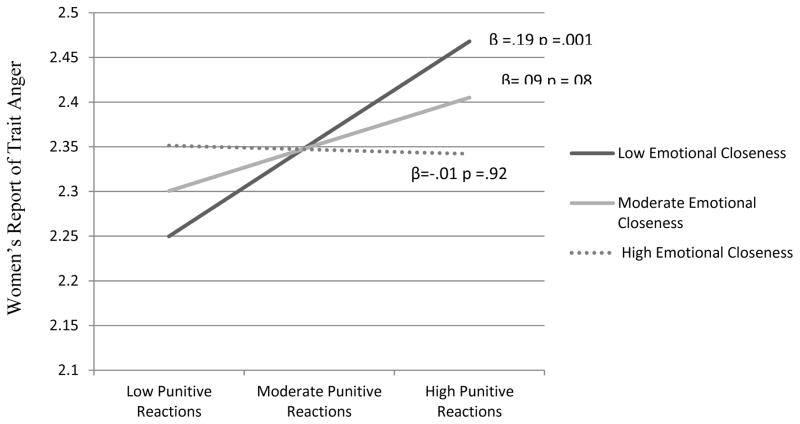

The two-way interaction between emotional closeness and mothers’ punitive reactions was significant for women (see Table 2). Follow-up tests of simple slopes (Aiken & West, 1991) revealed that young women’s retrospective accounts of their mother’s punitive reactions only predicted higher trait anger when they reported low emotional closeness, β = .19, p =.001. In contrast, women’s retrospective accounts of their mother’s punitive reactions did not predict higher trait anger when they reported moderate (β = .09, p =.08) or high (β = −.01, p = .92) emotional closeness (see Figure 1). This finding suggests that emotional closeness with their mother serves as a buffer against the deleterious effects of maternal punitive reactions to negative emotions for young women’s trait anger in adulthood.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of women’s emotional closeness to their mother in the association between punitive emotion socialization of negative emotions in childhood and young adult trait anger.

Discussion

The association between parents’ emotion socialization and children’s social and emotional development has been well established. However, the way in which emotion socialization in childhood has lasting effects on social and emotional outcomes in adulthood is less understood. The current study attempted to address this gap in the literature by examining whether emotional closeness moderated the relation between young adults’ recollected reports of their mother’s punitive responses to their negative emotions and their current trait anger. Further, a three-way interaction was tested to determine whether emotional closeness influenced this association in the same way for young men and women. Results indicated that for young women, emotional closeness moderated the association between recollected reports of maternal punitive reactions to negative emotions in childhood and adult anger expression. Specifically, maternal punitive reactions to women’s negative emotions in childhood were significantly associated with increased anger only when they reported low maternal emotional closeness with their mothers. For young men, there was no interaction between emotional closeness and punitive reactions but main effects were apparent; men’s reports of maternal punitive reactions to negative emotions were directly associated with increased anger expressions.

Previous research has indicated that parents use a greater number and variety of emotion terms with daughters than with sons (Adams, Kuebli, Boyle, & Fivush, 1995; Kuebli, Butler, & Fivish, 1995), and Benenson, Morash, and Petrakos (1998) found that mothers were physically closer, engaged in more mutual eye contact, and were rated higher on global enjoyment with their 5 year-old daughters than with their 5 year-old sons. Although men and women reported similar levels of maternal emotional closeness in the current study, the differential context in which men and women’s emotions are socialized could lead to a more complex and nuanced emotional connection between mothers and daughters that protect daughters from the negative effects of maternal punitive reactions to their negative emotions. Men and women may define emotional closeness differently based on these differential socialization experiences. In the current study, participants were simply asked how emotionally close they felt to their mother. Thus, a higher score on emotional closeness reflects participants’ perceived emotional closeness and does not reflect the characteristics that define the emotional bond. It is possible that even though young men and women in the current study reported similar emotional closeness to their mother, the characteristics of that emotional connection may be what buffers against the negative effects of punitive reactions.

Relatedly, young women are also thought to place a higher value on interpersonal relationships than men (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Ryan et al., 2005). For example, Kenny and Donaldson (1991) found that parental attachment, or a strong emotional bond, was more important to the well-being of daughters than sons. Thus, the value and internalized nature of a strong emotional connection may allow for a greater impact on developmental outcomes for young women. This idea is further supported by Chodorow’s (1999) theory that the mechanism that produces a more relational orientation in females as compared to males is that mothers bind themselves more closely to their daughters than their sons, and may even unconsciously identify more with their daughters; thus implying that mothers’ treatment of daughters makes them more dependent and more relational than males. Although the current study supports emotional closeness as a protective factor in the association between parental punitive reactions to children’s negative emotions and women’s trait anger in young adulthood, further research is needed to disentangle the specific mechanisms through which this takes effect takes place.

Results revealed that men reported that their mothers were slightly more likely to react punitively to their negative emotions than women, and empirical work has shown that in general boys display negative emotions such as anger more than girls (for a review refer to Brody & Hall, 1993). Therefore, in addition to being more likely to receive a punitive reaction to expressed anger, it is possible that there is a much greater frequency in the number of punitive reactions boys receive compared to girls. In the current study, we asked participants to report on how likely their mother would punish their negative emotions in childhood and did not assess how often they experienced these reactions. Thus, it could be that men encountered such situations more frequently in childhood leading to a stronger influence of the socialization of anger on men’s later anger expression. Given that men tend to express anger more frequently than women, it may be particularly important for young men to be provided with childhood opportunities that allow for the development of the necessary regulatory skills to display anger appropriately. Thus, regardless of emotional closeness, frequent and repeated punitive reactions to boys displays of negative emotion that do not allow for opportunities that teach adaptive regulatory strategies or expectations regarding appropriate display of anger may be associated with increased trait anger in young adulthood.

Although this study extends current literature and provides valuable insight into the association between the socialization of negative emotion in childhood and adult emotional functioning, it is not without limitation. First, adult children reported on their recollection of their mothers’ punitive reactions to their negative emotions in childhood. Although perception of maternal emotional socialization is important and provides a preliminary understanding, we cannot be sure that participants’ accounts of their mothers’ emotion socialization strategies coincide with the actual behaviors mothers’ employed during childhood. Further, although we attempted to account for the fact that young adults’ mental health might influence the way in which they recalled their parenting experiences, memories may in fact be shaped by later experiences. Specifically, the shifts that occur in the way that parents support and scaffold their children in late adolescence and early adulthood may impact the way in which young adults remember parents’ behaviors during childhood more generally. Therefore, longitudinal work from early childhood to adulthood is needed to assess whether mothers’ reports of emotion socialization during childhood is associated with later adult social and emotional outcomes in young adulthood, and future research is needed to determine whether frequency of the messages matters differently for young men and women. In addition, although large in size and likely more representative of the larger student body than typical samples of Psychology undergraduates, the sample utilized in the current study is one of convenience and comprised of students from one university in the southeastern United States. Thus, it is possible that findings may not be entirely generalizable. Finally, the current study is limited in that only self-report measures were utilized to assess all constructs. Therefore, there may be some conflation of effects given shared responder bias. Moreover, because it is socially undesirable to express high degrees of anger, participants may not have been entirely truthful or accurate when indicating how likely they were to respond in ways such as “flying off the handle” when angered. Although not exempt from social desirability bias, future work examining observed anger and parent reported anger would provide important additional insight.

The findings of this study raise a number of questions related to parental emotion socialization, emotional closeness, and gender differences. For example, what specific aspects of emotional closeness are most salient when considering it as a protective factor and how might the way in which men and women operationally define emotional closeness impact the extent to which emotional closeness can serve a buffering role. In addition, how might the socialization of positive emotion be related to later adult outcomes and how might gender be related to its impact. More exploration into these questions will provide additional insight into important nuances and lasting influences of emotion socialization across the lifespan.

References

- Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, Keating L. Psychosocial resources in first-year university students: The role of identity processes and social relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(1):81–91. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9019-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams S, Kuebli J, Boyle PA, Fivush R. Gender differences in parent-child conversations about past emotions: A longitudinal investigation. Sex Roles. 1995;33(5–6):309–323. doi: 10.1007/BF01954572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Family processes and the competence of adolescents and primary school children. Journal of Youth And Adolescence. 1989;18(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02139245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology. 1992;63(4):596–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Fraley B. Relationship closeness as including other in the self: Cognitive underpinnings and measures. Social Cognition. 1999;17(2):140–160. doi: 10.1521/soco.1999.17.2.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benenson JE, Morash D, Petrakos H. Gender differences in emotional closeness between preschool children and their mothers. Sex Roles. 1998;38(11–12):975–985. doi: 10.1023/A:1018874509497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Snyder M, Omoto AM. The relationship closeness inventory: Assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(5):792–807. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Hall JA. Gender and emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58(4):1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C. Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion. 2005;5(1):80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow N. The power of feelings: Gender and culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Dennis TA, Smith-Simon KE, Cohen LH. Preschoolers’ emotion regulation strategy understanding: Relations with emotion socialization and child self-regulation. Social Development. 2009;18(2):324–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Tamang B, Shrestha S. Cultural variations in the socialization of young children’s anger and shame. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1237–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8(3):161–175. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0803_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, Thwaites GA, Lynch RS, Baker DA, Stark RS, Eiswerth-Cox L. State–Trait Anger Theory and the utility of the Trait Anger Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43(2):131–148. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.43.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9(4):241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Mothers’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s temperament and anger behavior. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40(1):138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70(2):513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Bernzweig J. Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Description and Scoring. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R, Klimes-Dougan B. Socialization of discrete negative emotions: Gender differences and links with psychological distress. Sex Roles. 2002;47(3–4):115–128. doi: 10.1023/A:1021090904785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Watson JS. Early socio–emotional development: Contingency perception and the social-biofeedback model. In: Rochat P, editor. Early social cognition: Understanding others in the first months of life. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999. pp. 101–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz L, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(3):243–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harlaar N, Santtila P, Bjorklund J, Alanko K, Jern P, Varjonen M, Sandnabba K. Retrospective reports of parental physical affection and parenting style: A study of Finnish twins. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:605–613. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry CS, Robinson LC, Neal RA, Huey EL. Adolescent perceptions of overall family system functioning and parental behaviors. Journal of Child And Family Studies. 2006;15(3):319–329. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9051-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershcovis M, Turner N, Barling J, Arnold KA, Dupré KE, Inness M, Sivanathan N. Predicting workplace aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(1):228–238. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton N, Harris GT, Rice ME. On the validity of self-reported rates of interpersonal violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13(1):58–72. doi: 10.1177/088626098013001004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houltberg BJ, Henry CS, Morris A. Family interactions, exposure to violence, and emotion regulation: Perceptions of children and early adolescents at risk. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2012;61(2):283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00699.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, MacKinnon DP. Parents’ reactions to elementary school children’s negative emotions: Relations to social and emotional functioning at school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48(2):133–159. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2002.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny ME, Donaldson GA. Contributions of parental attachment and family structure to the social and psychological functioning of first-year college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;38(4):479–486. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.38.4.479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Zeman J. Introduction to the special issue of Social Development: Emotion socialization in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2007;16(2):203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00380.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopper BA, Epperson DL. The experience and expression of anger: Relationships with gender, gender role socialization, depression, and mental health functioning. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43(2):158–165. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.43.2.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Mendelson T, Lynch TR. Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: The mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(2):199–213. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebli J, Butler S, Fivush R. Mother-child talk about past emotions: Relations of maternal language and child gender over time. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9(2–3):265–283. doi: 10.1080/02699939508409011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta CZ. The role of emotions in the development and organization of personality. In: Thompson RA, Thompson RA, editors. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1988: Socioemotional development. Lincoln, NE, US: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta-Magai CZ. Emotional socialization: Its role in personality and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Smith J. Physical discipline and behavior problems in African American, European American, and Hispanic children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage And Family. 2002;64(1):40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00040.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullis RL, Brailsford JC, Mullis AK. Relations between identity formation and family characteristics among young adults. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(8):966–980. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03256156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, Leerkes EM, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Marcovitch S. African American and European American mothers’ beliefs about negative emotions and emotion socialization practices. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2012;12(1):22–41. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.638871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens G, Crowell J, Pan H, Treboux D, O’Connor E, Waters E. The prototype hypothesis and the origins of attachment working models: Adult relationships with parents and romantic partners. In: Waters E, Vaughn B, Posada G, Kondo-Ikemura K, editors. New growing points of attachment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 60. 1996. pp. 216–233. Serial No. 244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Zeichner A. Effects of trait anger and negative attitudes towards women on physical assault in dating relationships. Journal Of Family Violence. 2003;18(5):301–307. doi: 10.1023/A:1025169328498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Calkins SD, Nelson JA, Leerkes EM, Marcovitch S. Mothers’ responses to children’s negative emotions and child emotion regulation: The moderating role of vagal suppression. Developmental Psychobiology. 2012;54(5):503–513. doi: 10.1002/dev.20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Stashwick CK, Fitzmaurice G. Childhood and adolescent predictors of major depression in the transition to adulthood. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, La Guardia JG, Solky-Butzel J, Chirkov V, Kim Y. On the interpersonal regulation of emotions: Emotional reliance across gender, relationships, and cultures. Personal Relationships. 2005;12(1):145–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. Socialization of emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Schum JL, Jorgensen RS, Verhaeghen P, Sauro M, Thibodeau R. Trait anger, anger expression, and ambulatory blood pressure: A Meta-analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(5):395–415. doi: 10.1023/A:1025767900757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State–trait anger expression inventory professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Jacobs GA, Russell S, Crane RS. Assessment of anger: The state-trait anger scale. In: Butcher JN, Spielberger CD, editors. Advances in personality assessment. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. pp. 681–706. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima EA, Herrenkohl TI, Huang B, Whitney SD. Measuring child maltreatment: A comparison of prospective parent reports and retrospective adolescent reports. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(4):424–435. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, Feldman S. Relations of cohesion and power in family dyads to social and emotional adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Research On Adolescence. 1996;6(2):225–244. [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Klein DM. Family theories. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Widom C, Shepard RL. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 1. Childhood physical abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(4):412–421. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD. Keeping one’s cool: Trait anger, hostile thoughts, and the recruitment of limited capacity control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(9):1201–1213. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD, Gordon RD, Troop-Gordon W. Tracking the evil eye: Trait anger and selective attention within ambiguously hostile scenes. Journal of Research In Personality. 2007;41(3):650–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]