Abstract

Background

Although the diagnosis of childhood leukemia is no longer a death sentence, too many patients still die, more with acute myeloid leukemia than with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The European Union pediatric legislation was introduced to improve pharmaceutical treatment of children, but some question whether the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approach is helping children with leukemia. Some have even suggested that the decisions of EMA pediatric committee (PDCO) are counterproductive. This study was designed to investigate the impact of PDCO-issued pediatric investigation plans (PIPs) for leukemia drugs.

Methods

All PIPs listed under “oncology” were downloaded from the EMA website. Non-leukemia decisions including misclassifications, waivers (no PIP), and solid tumors were discarded. The leukemia decisions were analyzed, compared to pediatric leukemia trials in the database http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, and discussed in the light of current literature.

Results

The PDCO leukemia decisions demand clinical trials in pediatric leukemia for all new adult drugs without prioritization. However, because leukemia in children is different and much rarer than in adults, these decisions have resulted in proposed studies that are scientifically and ethically questionable. They are also unnecessary, since once promising new compounds are approved for adults, more appropriate, prioritized pediatric leukemia trials are initiated worldwide without PDCO involvement.

Conclusion

EMA/PDCO leukemia PIPs do little to advance the treatment of childhood leukemia. The unintended negative effects of the flawed EMA/PDCO’s standardized requesting of non-prioritized testing of every new adult leukemia drug in children with relapsed or refractory disease expose these children to questionable trials, and could undermine public trust in pediatric clinical research. Institutions, investigators, and ethics committees/institutional review boards need to be skeptical of trials triggered by PDCO. New, better ways to facilitate drug development for pediatric leukemia are needed.

Keywords: childhood leukemia, better medicines for children, pediatric drug development, therapeutic orphans, therapeutic hostages, ghost studies, pediatric investigation plan

Cancer and leukemia in children

Childhood cancer has moved from just a footnote in pediatric textbooks to the major cause of death from disease in the children of developed countries.1 Diseases that in the past caused horrendous death rates in children can today either be prevented – by vaccination, better nourishment, housing, hygiene, and more – or be treated by antibiotics, antivirals, and other medications. The increasing capacity to overcome these child killers of the past has given child cancer a sad prominent position. Together, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) make up approximately one-third of all pediatric cancer diagnoses.2 The diagnosis of leukemia is no longer an automatic death sentence, as it was a century ago. But survival of child cancer is not like overcoming a serious infection that a year later is just a bad remembrance. For both ALL and AML, treatment fundamentally is based on cytotoxic drugs that cause intracellular damage, resulting in the death of leukemia blasts.3,4 Despite remarkable improvement, the prognosis of certain high-risk groups of leukemia and of relapsed disease remains poor, more so in AML but also in a small percentage of children with ALL.5–7

Specialized centers differentiate patients at first diagnosis into subgroups. Patients are then treated in a risk-adapted fashion; that is, low-risk patients receive relatively moderate chemotherapy (CT), and high-risk patients receive rather toxic doses.6,7 Once treatment has started, the waiting and despair starts: Will remission be achieved? Will it hold? In patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) leukemia, a second round of treatment starts, but the chances for a new remission are less good. Because high-risk patients are identified relatively soon, it is debatable whether they might be better served by enrollment into Phase II window studies, where early exposure to a novel drug might lead to improved efficacy compared to the conventional regimen or later exposure to the novel drug.5

In adult cancer, there is a competitive search for new ways to help. Only a part of this competition is guided by science. Patients in despair can also fall prey to quack healers and swindlers. Even within the science-driven approach(es), the competition is fierce. Academic researchers, big pharmaceutical companies, and small start-up companies compete. Companies either invest their own money or find money on the financial investment market or in the philanthropic world. The research and development machinery of the big pharmaceutical industry may be successful to some degree but has also become bureaucratic and inert. Increasingly, big companies let drug discovery be done by start-up companies. If a start-up company reaches certain milestones in development, it will be bought entirely, sell its compound, or codevelop it with a big company. The litmus test in drug development is success in real patients. The pivotal clinical trials aim at regulatory approval. To accept or reject approval is the key task for regulatory authorities.

As outlined by many authors, the pediatric cancer market is rather limited due to its rarity.1,3,8,9 There is also broad agreement within the pediatric oncology clinical community that major steps forward need to come out of biomedical research, involving our increasing understanding of the body on a cellular and subcellular level.1,3,5,9 Furthermore, in cancer and even in leukemias, the adult disease differs considerably from the childhood disease. There has been considerable progress toward targeted therapy in adult oncology, and there is broad agreement that comparable steps toward better treatment of childhood cancer would be desirable but difficult to achieve.

A complex, highly successful industry has evolved, and continues to evolve, that develops products (drugs, devices, and diagnostic products) that can prevent, cure/control, or diagnose human diseases. This industry is market-driven but is also influenced by numerous interactions with government, academia, and society. Governmental influence comes largely from regulatory bodies that approve products for marketing. Regulatory authority is based on legislation, much of which was developed to deal with patient harm caused by an unregulated pharmaceutical industry such as the use of ethylene glycol in sulfanilamide,10 and deformed newborns from thalidomide.11,12 Legislation enacted to prevent such public health disasters resulted in the current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)12 and later its counterparts in other regions, in the European Union (EU) today the European Medicines Agency (EMA)13 that works as an umbrella with the EU national authorities.

This review focuses on the effects of the EU pediatric legislation14 designed to force the pharmaceutical industry to consider children in drug development, and takes pediatric leukemia as a paradigm. We start with a discussion of some important points that are frequently misperceived.

The US pediatric legislation was not designed to and does not facilitate the development of better medicines for children. Details of the US pediatric legislation have been described in detail elsewhere.3,15 In a nutshell, the original first law, Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act, offered a reward for additional pediatric data, mostly pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and sometimes additional efficacy data, for existing adult drugs. Its goal was to provide labeling on whether or how drugs developed for adults (and that still had patent protection) should be used in children. This very successful legislation was of great interest to the research-based pharmaceutical industry that had started to feel the threat of patent expiry of several top-selling products. A second legislation, Pediatric Research Equity Act, gave the FDA the authority to mandate clinical trials be done in children for new drugs where a relevant pediatric use could be expected because the same disease existed in both adults and children. Such additional information is precious, but its value needs to be differentiated for the different childhood age groups. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of drugs are different between children and adults, but the clinical relevance of this is greater in infants and young children than in adolescents. The US pediatric legislation promoted the use of the development machinery of the pharmaceutical industry for the first time to do pediatric clinical trials,16 but it was never designed to develop new drugs specifically for children. In this sense, the term “pediatric drug development”17,18 is misleading, as so far, this term addresses more the inclusion and co-consideration of children into the drug development process for adult drugs.

-

When academics discuss the history of pediatric oncology drug development, they emphasize the key role of academic researchers.In the era after Farber,The merits of Farber’s, Frei’s, and Pinkel’s achievements are beyond question. But the descriptions above fall short of capturing how this newly evolving framework came about. How did Dr Farber have access to aminopterin? Where did the “several new antileukemia drugs”22 come from? They were “around” because they could be ordered or could be produced in a local laboratory – because the chemicals and laboratory equipment were “available”. The history of pediatric oncology was the systematic study and use of drugs in children developed and brought to the market for adult patients by the – then – chemical industry. New anticancer drugs became broadly available because they were FDA-approved. Adamson describes how the 5-year survival for children with ALL improved from the 1970s through the 1990s and that in this period major new drug discoveries happened.Quite remarkably, almost all of the drugs used in the treatment of childhood ALL that drove this improvement were primarily discovered and developed in the 1950s and 1960s.1

Where did they come from? They were not parachuted by god to the FDA for approval. They had to be developed, tested, and made available to gain approval by the FDA. This included transition from small batches to full-size industrial production. This required skills in addition to scientific curiosity and the zeal to make a clinical career. In other words, the emphasis on academic achievements ignores a critical part of this story that is relevant for any attempt to use the pharmaceutical industry’s research, discovery, and development machinery with the aim of developing better drugs for children.

Regulatory authorities are crucial in keeping quack medicines and dangerous compounds from the market and (from the 1960s) in demanding proof of efficacy of new drugs before their market introduction, including anticancer drugs. Regulators made no specific contribution to pediatric oncology. All FDA-approved drugs, now “around”, were used off-label, and many of them are still not FDA-approved for use in children.8,15,16

The pharmaceutical industry is not static. Companies compete, merge, go through acquisition, or go bankrupt. When the new era of targeted medicine started with the success of the first targeted medicines, the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) leukemia, there were great expectations that personalized medicine would develop rapidly, but successes were slower and more limited than expected. Increasingly large pharmaceutical companies rely less on in-house research and development and more on licensing in new compounds that have been developed by smaller, more flexible start-up companies.

The EU pediatric legislation was a follow-up to the US legislation. Superficially, it might appear comparable, but there are considerable differences. The key difference is that the EU version makes pediatric development for each new adult drug mandatory, unless the adult disease does not exist in children, the drug is unsafe, or no additional therapeutic benefit can be expected in children. Discussion and decisions about what should be done in children must be performed long before proof of efficacy: at the end of Phase I. At this time point, the submission of a pediatric investigation plan (PIP) is expected. The process by which the PIP is then discussed with the EMA pediatric committee (PDCO) takes ∼1 year. Without an accepted PIP, approval of the drug is blocked. Details about PIP negotiation are published elsewhere.3,5,23,24 The EU pediatric legislation is based on the assumptions that the key to better medicines for children lies in biomedical research, which to a large degree is run by the pharmaceutical industry, and that this industry needs guidance by the EMA, whether wanted or not, to test and label drugs for use in children because the off-label use of drugs can be unhelpful or even dangerous. While true for many drugs specifically in young children and infants, this is not true for pediatric oncology drugs.

The off-label use of oncology drugs is routine in pediatric oncology and in the hands of well-trained specialists. Such use has saved thousands of lives. Pediatric oncology is certainly not good justification for the introduction of the pediatric legislation. For decades, the childhood cancer cooperative groups have prioritized and systematically tested all promising drugs in children with cancer.

The basic question this paper asks is the following: Will the EMA/PDCO’s decisions advance the treatment of childhood leukemia? To answer this question, all PDCO decisions related to childhood leukemia were therefore examined.

The EMA AML standard PIP

For AML, EMA and PDCO have developed a “standard PIP” to guide pharmaceutical companies that develop new drugs against adult AML.25 This document allows insight into PDCO’s logic. It starts with the explanation that there are still unmet therapeutic needs in children with newly-diagnosed AML as well as in those with R/R AML and continues that all pediatric AML subsets,

[…] should be discussed in the PIP documentation and the PIP indication should target 2 or 3 of the following subsets, selected based on a scientific rationale for the medicine and with the objective to improve the overall outcome in AML.

Table 1 shows these subsets.

Table 1.

Subgroups in the EMA/PDCO AML standard PIP

| • Patients with newly-diagnosed high-risk AML: need for a more efficacious treatment as part of a first-line induction regimen, in particular when there is a good rationale for use during first-line treatment, such as the individual disease biology (eg, FLT3 mutations with high allelic ratio etc) or the potential for reduction of toxicity. |

| • Patients with AML that is resistant to first or to second line induction treatment: need for an efficacious treatment as part of a re-induction regimen. |

| • Patients at the time of diagnosis of relapse after HSCT/second or subsequent relapse: need for an efficacious treatment that is not overly toxic in this subset of patients who likely had high cumulative previous treatment exposure, likely including at least one prior transplant procedure. |

| • Patients with secondary AML: need for an efficacious treatment. |

| • Patients at the time of diagnosis of early first relapse: need for a more efficacious treatment as part of a treatment regimen. |

| • Patients at the time of diagnosis of first relapse (other than early): need for a more efficacious treatment as part of a treatment regimen. |

| • Patients with APL: need for safer treatment to be used during induction. |

| • Patients with AML in Down syndrome: Needs may exist, specifically for non-cytotoxic or “targeted” medicines to reduce treatment toxicity. Needs may be less in patients younger than 1 year of age and in those with FAB M6 or M7, compared to other patients with AML in Down syndrome. |

| • Congenital AML, extramedullary AML. |

Notes: The content of this table contains the wording of the AML pediatric subgroups from the AML standard PIP. Underlinings, explanations in brackets, and quotation marks are exact copies of the AML standard PIP.

Abbreviations: EMA, European Medicines Agency; PDCO, pediatric committee; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; PIP, pediatric investigation plan; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; FAB, French–American–British.

With the standard PIP’s logic, companies must for each new anti-AML drug pick two to three AML subgroups and “propose” clinical trials and other measures (child-friendly formulations, preclinical toxicity studies, and more). If a company does not “propose” enough, the PIP will be refused, and the compound’s approval is blocked, no matter how well it might work in adults. However, childhood leukemia is rare, and patients with R/R AML or ALL are even rarer.

EMA’s PDCO cancer decisions

The EMA website provides both a quick look at the current pipeline of industry’s pediatric leukemia drugs and a listing of PDCO decisions concerning these drugs. A search was conducted at “Opinions and decisions on paediatric investigation plans” by “browsing from a to z”, keywords, or therapeutic area. As of July 27, 2015, there were 122 PIP decisions identified under “oncology”.26 Waivers (no pediatric development required) and wrongly classified PIPs, etc were discarded. In one case, the EMA overview listed a PIP modification, but the document shows it is now a waiver. Two decisions were listed twice. For a colony-stimulating factor (CSF), there were two decisions: one to refuse a waiver (EMEA-001042-PIP01-10) and a later PIP decision (EMEA-001042-PIP02-11). Waiver requests are either accepted or rejected. If rejected, the applicant must start a new PIP procedure. The CSF manufacturer submitted a new PIP and got approval, so only the CSF PIP decision was counted.

Published PIP decisions have two parts. The first pages declare officially that the PDCO has given an opinion and has come to a decision. In the second part, under “Opinion of the Paediatric Committee”, key information is listed: name of the drug, the disease in which it should be developed for children, its pharmaceutical form, etc. The key elements, that is, which clinical studies and other actions must be done (after the “applicant” has “proposed” them), are summarized in a table at the end of the PIP decision. Some of the “conditions” listed under the headline “Opinion of the Paediatric Committee” were not completely congruent with the clinical studies. Several drugs target both adult ALL and AML. First, all compounds from the original 122 PIP opinions that contained a type of leukemia under the headline “Opinion of the Paediatric Committee” were double-checked to see if the studies corresponded to these two conditions. For example, the rituximab PIP EMEA-000308-PIP01-08-M02 has as condition(s) “Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” and “Treatment of autoimmune arthritis”, but the key elements list a clinical study on “B-cell lymphoma (excluding primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma), Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma/leukaemia”. Therefore, rituximab was included. Obinutuzumab has under the headline “Opinion of the Paediatric Committee” as condition(s) “Treatment of mature B-cell lymphoma” and “Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia”, but the PIP study listed is only in children with mature B-cell lymphoma; hence, the obinutizumab PIP was not included into the leukemia PIP analysis.

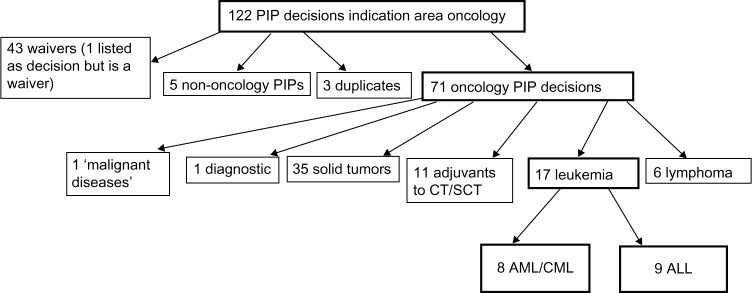

The classification of all compounds and additional explanation is given in Supplementary materials (Table S1–S4), including detailed explanation of misclassifications and double listings (Table S2–S4). The algorithm to identify the leukemia PIPs is given in Figure 1. The 17 PIP decisions for AML and ALL are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Classification of PIP decisions.

Abbreviations: PIP, pediatric investigation plan; SCT, stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CT, chemotherapy.

Table 2.

AML/CML PIP Decisions

| Drug, PIP # | Clinical Studies | Until |

|---|---|---|

|

Bosutinib EMEA-000727-PIP01-09 |

1. OL MC uncontrolled, DF study to evaluate PK, S and A of bosutinib in 10 to <18 years w/Ph+ CML in chronic phase resistant/intolerant to prior TKI therapy | DEC 2016 |

| 2. Bioequivalence study with bosutinib in adults with paediatric age-appropriate formulation. | ||

|

Decitabine EMEA-000555-PIP01-09-M04 |

1. OL MC multiple dose trial to evaluate PK, S and A of decitabine in sequential combination with cytarabine in children 1 month to <18 years with AML | JUL 2021 |

| 2. OL, MC, R controlled trial to evaluate S and E of decitabine in sequential combination with cytarabine compared with standard of care induction therapy in children 1 month to <18 years with AML | ||

|

Elacytarabine EMEA-001121-PIP01-10 |

1. OL, uncontrolled, dose-escalating trial to evaluate S, tolerability and PK of elacytarabine in patients 1 month to <18 years w/R/R acute leukaemia | SEP 2019 |

| 2. OL externally controlled trial to evaluate S, A and E of elacytarabine in combination with liposomal daunorubicin compared to fludarabine, cytarabine and daunorubicin in patients 1 month to <18 years w/R/R AML with an initial DE stage to S of elacytarabine in combination with liposomal daunorubicin | ||

|

Midostaurin EMEA-000780-PIP01-09-M01 |

1. OL DE, single-agent, MC, age-stratified trial to evaluate toxicity, PK, PD, S and A of midostaurin in 3 months to <18 years w/R/R ALL or AML | DEC 2019 |

| 2. OL DE, randomized, active-controlled, age-stratified, MC trial to evaluate toxicity, PK, PD, S and A in children 3 months to <18 years with newly-diagnosed AML with certain FLT3 TKD mutation burden | ||

| 3. Pop PK/PD and outcome model to support extrapolation of E | ||

|

Nilotinib EMEA-000290-PIP01-08-M03 |

1. Study to compare bioavailability of nilotinib when administered as intact capsule or the capsule content mixed with yogurt or apple sauce in adult volunteers | SEP 2015 |

| 2. Multiple-dose OL single-agent, non-controlled trial to evaluate PK, PD, S and A in patients 1 to <18 years w/Ph+ CML in chronic or accelerated phase intolerant or resistant to imatinib- and/or dasatinib, or with R/R Ph+ ALL | ||

| 3. Multiple-dose OL single-agent, non-controlled, MC trial to evaluate PK, S and A in patients 1 to <18 years w/Ph+ CML in chronic or accelerated phase, intolerant or resistant to imatinib- or dasatinib or with newly diagnosed Ph+ CML in chronic phase | ||

|

Ponatinib EMEA-001186-PIP01-11 |

1. OL, single-agent, DE, MC trial to investigate tolerability, S and A of ponatinib in children 1–17 years with malignant disease for which no effective treatment is known, and with an expansion cohort of children with chronic phase CML | DEC 2020 |

|

Volasertib EMEA-000674-PIP02-11 |

1. OL, non-controlled, DE trial to evaluate PK, PD, tolerability and toxicity of volasertib in patients 2 to <18 years w/acute leukaemia or advanced solid tumour, for whom no effective treatment is known | DEC 2023 |

| 2. OL, DE trial to evaluate PK, PD, tolerability, toxicity, S and A of volasertib added to intensive CT in children | ||

| 3 months to <18 years with AML after failure of front-line intensive CT 3. OL, R, controlled trial to evaluate S and E of volasertib integrated with a standard intensive CT regimen in children 3 months to <18 years with AML after failure of the front-line intensive CT | ||

|

Vosaroxin EMEA-001450-PIP01-13 |

1. OL, uncontrolled, MC, DE trial to evaluate tolerability, S, PK and A of vosaroxin in children with acute leukaemia 1 month to <18 years | JUL 2023 |

| 2. OL, uncontrolled, MC trial to evaluate S and A of vosaroxin in combination with FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) in children 1 month to <18 years with a first relapse of AML |

Abbreviations: OL, open label; PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics; DF, dose-finding; DE, dose escalating; w/, with; R/R, relapsed or refractory; BE, bioequivalence; Pop PK/PD, Population PK/PD; MC, multicenter; E, efficacy; S, safety; A, activity; R, randomized; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic/lymphocytic/lymphoid leukemia; Ph+, Philadelphia positive; CT, chemotherapy; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; PIP, pediatric investigation plan.

Table 3.

ALL PIP decisions: clinical studies

| Autologous T-cells transduced with lentiviral vector containing a chimeric antigen receptor directed against CD19 (CTL019), EMEA-001654-PIP01-14 | 1. OL SA posology-finding study to evaluate S and F of redirected autologous T-cells engineered to contain anti-CD19 attached to TCRzeta and 4-1BB signaling domains (CAR-19 cells) in patients 1 year to <18 years (and adults) with a CT-resistant or CT-refractory CD19+ leukemia or lymphoma |

| 2. OL SA, single-dose study to evaluate S and A of CTL019 in 2 years to <18 years at the time of initial diagnosis (and adults) with CD19+ B-cell acute LL/CD19+ B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma refractory to standard CT, relapsed after SCT, or otherwise ineligible for allogeneic SCT | |

| 3. OL SA single-dose study to evaluate S and A of CTL019 in 3 years to <18 years (and adults) with | |

| 4. CD19+ B-cell ALL refractory to standard CT, relapsed after SCT, or ineligible for allogeneic SCT OL two-cohort study to evaluate manufacturing and S of CTL019 in <3 years, weighing ≥6 kg, with CD19+ B-cell ALL/CD19+ B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma at high risk for relapse and at relapse or refractory stage | |

| Navitoclax (ABT-263), EMEA-000478-PIP01-08-M01 | 1. OL, S and PK study of ABT-263 single-agent and combination therapy in pediatric patients from 28 days to <18 years of age with relapsed or refractory lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| 2. R, controlled, S and A study of ABT-263 in combination with a chemotherapeutic backbone in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma | |

| Blinatumomab, EMEA-000574-PIP02-12 | 1. MC, OL, multiple-dose, dose-escalation trial to evaluate PK, PD, toxicity, S, and antitumor activity of blinatumomab in children from birth to <18 years of age with a relapse of B-precursor ALL involving the bone marrow or a refractory ALL and for whom no effective treatment is known, with an extension phase R, controlled, adaptively designed, OL trial to evaluate the PK, S, and E of blinatumomab compared to multiagent consolidation CT in children from 1 month to <18 years of age with a first, high-risk relapse of B-precursor ALL PK–PD analysis to inform the dose for study 2 |

| Dasatinib, EMEA-000567-PIP01-09-M04 | 1. OL MC dose-escalation trial to evaluate PK and S of dasatinib in children from 2 years to <18 years (and in adults) with recurrent or refractory solid tumor or imatinib-resistant Ph+ leukemia |

| 2. OL MC dose-escalation trial to evaluate PK and S of dasatinib in children from 1 year to <18 years with Ph+ CML or acute leukemia | |

| 3. OL MC trial to evaluate PK, S, and E of dasatinib in children 1 year to <18 years with Ph+ CML of all phases (including treatment-naïve patients in chronic phase) or relapsed or refractory Ph+ ALL | |

| Imatinib, EMEA-000463-PIP01-08-M03 | 1. OL MC non-R dose-escalation trial to evaluate S and E of CT, hematopoietic SCT, and imatinib in children from 1 year to <18 years (and young adults) with ALL |

| 2. OL MC R trial to evaluate S, A, and E of imatinib on top of CT and in combination with hematopoietic SCT in children 1 year to <18 years with ALL | |

| 3. Development and validation of an integrated physiology-based PK and pop PK model | |

| 4. For the indications myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative diseases associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor gene rearrangements, hypereosinophilic syndrome and/or chronic eosinophilic leukemia with FIP1L1-platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene rearrangement, kit (CD 117)-positive gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, the following studies are separately listed | |

| • Study 3: same as for condition treatment of Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL translocation)-positive ALL | |

| • Study 4: measure to extrapolate efficacy to the pediatric population | |

| l-Asparaginase encapsulated in erythrocytes, EMEA-000341-PIP02-09-M01 | 1. Double-blind, dose-comparative, R, repeat-dose, MC, active-controlled trial to evaluate PK, PD, S, and immunogenicity of l-asparaginase encapsulated in erythrocytes in children from 1 year to <18 years (and in adults) with ALL |

| 2. OL, R, single-dose, MC, active-controlled trial to evaluate PK, S, and PD activity of l-asparaginase encapsulated in erythrocytes in children from 1 year to <18 years (and in adults) with first relapse of ALL, with and without asparaginase hypersensitivity | |

| 3. OL, R, MC, active-controlled trial to evaluate S, PD equivalence/comparative efficacy of l-asparaginase encapsulated in erythrocytes in children from birth to <18 years with newly-diagnosed ALL | |

| Mercaptopurine, EMEA-000350-PIP01-08 | 1. OL, single-dose, single-center, R, crossover trial to assess the bioequivalence of oral mercaptopurine suspension to the tablet formulation in adults |

| Recombinant l-asparaginase, EMEA-000013-PIP01-07-M03 | 1. R, parallel-group, blinded, single-center, multiple-dose trial to evaluate PK, PD, A, and S of recombinant l-asparaginase compared to native Escherichia coli asparaginase in children from 1 year to <18 years of age (and adults) with newly-diagnosed ALL |

| 2. R, MC, double-blind trial to evaluate S, PD equivalence, and E of recombinant l-asparaginase compared to native E. coli asparaginase in children from 1 year to <18 years of age (and adults) with newly-diagnosed ALL | |

| 3. Noncontrolled, MC trial to evaluate PD, A, and S of recombinant l-asparaginase in children from birth to <1 year of age with newly-diagnosed ALL | |

| 4. Three studies, listed separately under lymphoblastic lymphoma: “same as for condition treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia” | |

| Rituximab, EMEA-000308-PIP01-08-M02 | 1. OL R, controlled, parallel-group, MC trial to evaluate PK, PD, S, and E of rituximab add-on to standard CT in children 6 months to <18 years with advanced stage B-cell lymphoma (excluding primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma), Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma/leukemia |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; PIP, pediatric investigation plan; OL, open-label; SA, single-arm; S, safety; F, feasibility; A, activity; CT, chemotherapy; SCT, stem cell transplantation; MC, multicenter; PK, pharmacokinetics; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; E, efficacy; R, randomized; Pop, population; PD, pharmacodynamics; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; LL, lymphoblastic lymphoma.

With the exception of mercaptopurine, all AML and ALL PIP decisions have an open-label dose-escalating trial plus, in most cases, additional studies of population pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, safety, efficacy, feasibility, or activity. There is no prioritization of the compounds. As pointed out by others, this is a drug-centered and not a disease-centered approach.1,5 It requests the same studies for every drug being developed for adult leukemia, an approach that might make sense if leukemia were as common in children as it is in adults and if childhood leukemia were the same disease as adult leukemia. However, cancers in children, including AML and ALL, are different from cancers in adults, and are much rarer.

The EMA/PDCO’s decisions appear to be based on the assumption that every new, but as yet unstudied, adult antileukemia compound has an equal chance of having a beneficial effect in children as well.

There are three problems with the EMA/PDCO’s decisions. Firstly, they reflect an unprioritized, drug-centric approach.1,5 Secondly, the number and type of studies might be justified and possible if there were an unlimited number of pediatric patients, but there are not. Finally, the approach ignores the fact that these drugs will be and are being studied in other countries. All studies compete for both investigators and patients worldwide.

To analyze to what degree the PIPs translate into clinical trials that compete for patients, all drugs with a leukemia PIP decision were looked for in the database http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. This is the world’s largest registry of clinical trials, run by the US National Library of Medicine. Currently, it includes registrations of >190,000 trials from >170 countries. In comparison, the EU clinical trials database http://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu is less user friendly and minimally helpful for research like this. For example, the search terms “rituximab leukemia children” resulted in three hits, of which one was in adults only, and the search terms “decitabine children leukemia” resulted in two hits, of which one was a study in adults.

As shown in Table 4, once drugs are approved in adults, they can be used in multiple studies conducted worldwide to investigate their potential use in children. However, as illustrated by some drugs selected from Tables 2 and 3, there are major differences between the PDCO approach and the more selective approach taken outside EMA/PDCO (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pediatric leukemia studies of all PIP leukemia compounds in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Compound | Number of studies | Completed | Recruiting | Active, not recruiting | Terminated | Status unknown | Suspended | Withdrawn | Not yet recruiting | Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decitabine | 29 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Elacytarabine | 0 | |||||||||

| Midostaurin | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Nilotinib | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Ponatinib | 0 | |||||||||

| Volasertib | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Vosaroxin | 0 | |||||||||

| Bosutinib | 0 | |||||||||

| Navitoclax (ABT-263) | 0 | |||||||||

| Blinatumomab | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Dasatinib | 23 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 1 | |||||

| Imatinib | 66 | 40 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Rituximab | 73 | 26 | 22 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| l-Asparaginase GRASPA | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mercaptopurine | 116 | |||||||||

| Recombinant l-asparaginase | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Autologous T-cells against CD19 |

Notes: The search term “imatinib children leukemia” gave 85 hits on July 21, 2015. Of these studies, 19 were studies on other compounds, mostly TKIs resistant to imatinib, or were studies in adults. The studies excluded from this statistics were NCT01844765, NCT00306202, NCT00852709, NCT01077544, NCT00042003, NCT00042016, NCT00041990, NCT00866736, NCT00973752, NCT00538109, NCT00990249, NCT00427791, NCT01429610, NCT01392170, NCT01004497, NCT01698905, NCT01460498, NCT00511069, and NCT00167180. The search term “rituximab children leukemia” gave 78 hits on July 22, 2015. Most studies accepted a broad age range (eg, study NCT00427557 – 1 month to 80 years). Five study descriptions showed that they were in adults only, so they did not enter into the counting. We did not exclude those studies that did not give a precise age of participants. The search term “rituximab leukemia” gave 340 hits, so the database is able to differentiate between adults and children, and we assume that in most studies without clear age description, children are/were included.

Abbreviations: PIP, pediatric investigation plan; GRASPA, erythrocytes encapsulating l-asparaginase; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Decitabine, for example, is a DNA-hypomethylating agent that induces differentiation and apoptosis of leukemic cells, and is a well-tolerated alternative to aggressive CT. It is FDA-approved for myelodysplastic syndrome but is not approved for AML.27 There are currently 198 clinical studies with decitabine listed in clinicaltrials.gov, and 29 with the search terms “decitabine leukemia children”. Out of these 29, 16 are listed as already being completed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Decitabine clinical trials in leukemia children

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Decitabine + cytarabine in R/R AML | 01853228 | 1 month to 18 years | Jannsen Pharma |

| 2 | Decitabine in R/R AML or ALL | 00042796 | ≤21 years | NCI |

| 3 | Decitabine + genistein in ped R/R malignancies | 02499861 | 2–21 years | St Justine’s Hospital |

| 4 | Epigenetic reprogramming in relapsed AML | 02412475 | ≤25 years | Medical College Wisconsin |

| 5 | Decitabine + vorinostat + CT in relapsed ALL | 1483690 | 1–21 years | TACLC |

| 6 | AR-42 + decitabine in AML | 01798901 | ≥3 years | OSUCCC |

| 7 | Decitabine + vorinostat + CT in R/R ALL or LL | 00882206 | 2–60 years | University of Minnesota |

| 8 | Low-dose decitabine in R/R ALL | 00349596 | ? | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 9 | Decitabine + GO in AML and HR MDS | 00882102 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 10 | Decitabine + valproic acid in R/R leukemia and MDS | 00075010 | ≥2 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 11 | Imatinib + decitabine in CML | 00054431 | ? | NCI |

| 12 | Decitabine for MDS and AML before allo-HSCT | 01806116 | 8–65 years | Soochow Hospital, People’s Republic of China |

| 13 | Decitabine + PBSCT in relapsed leukemia, MDS, CML after BMT | 00002832 | ≤60 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 14 | Decitabine with induction CT in AML | 01177540 | 1–16 years | Eisai Pharma |

| 15 | Decitabine with or without valproic acid in MDS and AML | 00414310 | ? | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 16 | Decitabine + GO in AML and HR MDS | 00968071 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 17 | Decitabine in blast-phase CML relapsed to imatinib | 00042003 | ≥2 years | Astex Pharma |

| 18 | Decitabine in CML relapsed to imatinib | 00042016 | ≥2 years | Astex Pharma |

| 19 | Decitabine in CML relapsed to imatinib | 00041990 | ≥2 years | Astex Pharma |

| 20 | Decitabine for maintenance after first CT for AML | 00416598 | 15–59 years | NCI |

| 21 | Decitabine in AML and MDS after allo-HSCT | 02264873 | 1–30 years | University of Florida |

| 22 | Decitabine and two CT regimens in AML | 00943553 | 1–16 years | Eisai Pharma |

| 23 | CT + PBSCT in CML or acute leukemia | 00002831 | 15–55 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 24 | Phase I, dose-escalation study of decitabine | 00067808 | ? | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 25 | Decitabine in MDS after azacytidine failure | 00113321 | 18–85 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 26 | Decitabine in MDS | 00003361 | ≥15 years | MSKCC |

| 27 | CHG vs decitabine in HR MDS | 01417767 | 16–80 years | Shanghai Hospital, People’s Republic of China |

| 28 | Decitabine + cytarabine in MDS | 01674985 | 10–90 years | CAMMS |

| 29 | Decitabine in MDS | 02060409 | 17–90 years | Samsung Medical Center |

Notes: The search terms “decitabine leukemia children” gave 28 hits; two were in patients ≥60 years and were removed (NCT02085408 and NCT01041703). Studies number 27–29 came up with the search terms “decitabine children”, and as they aim at MDS and include also pediatric patients, they were added.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; R/R, relapsed or refractory; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NCI, National Cancer Institute; CT, chemotherapy; TACLC, Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia Consortium; OSUCCC, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center; LL, lymphoblastic lymphoma; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; HR, high-risk; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; PBSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; CAMMS, Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences.

There are also 66 trials listed for imatinib, 40 of which are listed as already completed. In contrast, bosutinib, the fourth TKI developed after imatinib, was FDA-approved in 2012 (for adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast-phase Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia [CML] with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy) and has had conditional EMA approval in adults since 2013. The 2010 PIP decision on bosutinib lists a number of studies that are scheduled to be completed by December 2016. However, there is not a single pediatric leukemia study with bosutinib listed in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

As these examples illustrate, where clinicians (and parents) have hope, a number of adult and pediatric studies are opened around the world as soon as the compound is available for any indication. The list of sponsors of these studies includes pharmaceutical companies, university hospitals, and cancer research centers in the US and worldwide (Table 4). The large number of ongoing and completed, non-EU decitabine studies raises questions about the relevance of the apparently redundant PIP studies (Table 5).

The first study in the decitabine PIP (EMEA-000555-PIP01-09-M04, decision in 2013) corresponds to study number 1 in Table 5. The study is recruiting. Both clinical studies in this PIP should be completed by July 2021 (Table 2). Study number 1 is to be performed in R/R AML. Of the other decitabine studies, number 2 in Table 5, decitabine in children and young adults with R/R AML or ALL, was performed in 2002–2005 by the US National Cancer Institute. Furthermore, 27 other studies of decitabine in pediatric leukemia were started, 16 of which are already completed (Table 5). It is unlikely that the two PIP studies will add any relevant clinical data to that coming from the multiple clinical studies ongoing or already completed, but they kept/will keep the enrolled patients from participating in other studies with potentially more promising agents, some of which are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Cytarabine is part of the current standard induction CT for AML. Elacytarabine, an analog of cytarabine, was developed with the intent of overcoming resistance mechanisms. It is not yet clear if elacytarabine is an effective alternative to standard cytarabine in adult patients with acute leukemias, especially when used in combination with additional agents such as anthracyclines. A Phase III clinical trial failed to show superiority of elacytarabine over the investigator’s choice of therapy for R/R AML.28 The elacytarabine PIP decision dates from 2012, and the studies should be completed by 2019 (Table 2). The authors were unable to find a single pediatric clinical leukemia trial with this compound, and in view of the negative results mentioned by DiNardo et al,28 it appears questionable whether the two PIP studies make clinical or ethical sense.

Midostaurin is a first-generation FLT3 receptor TKI investigated for the treatment of AML and myelodysplastic syndrome. Early FLT3 inhibitors (including sunitinib, midostaurin, and lestaurtinib) demonstrated significant promise in preclinical models of FLT3-mutant AML. However, many of these compounds failed to achieve robust and sustained FLT3 inhibition in early clinical trials. Second-generation FLT3 inhibitors are now under development,29 and it is not known if they will fare better than the first-generation FLT3 TKIs. The search terms “midostaurin leukemia children” in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov identified two trials, both of which are completed (Table 6). There are 20 additional adult midostaurin studies in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, including completed trials. The completed pediatric midostaurin trials correspond to the first two PIP studies listed in Table 2. The PIP was submitted in 2009 (the 09 in PIP number EMEA-000780-PIP01-09-M01 stands for 2009) and was modified once in 2014 (M01). The PIP studies should be completed by 2019. The first study in Table 6 was performed in patients 3 months to <18 years in 2009–2014, and the second one in patients ≥14 years in 2009–2012. Was this early exposure justified?

Table 6.

Midostaurin pediatric leukemia trials in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OL, DE, S, T, and PK study of twice-daily oral midostaurin and to evaluate preliminary clinical and PD response in pediatric patients with R/R leukemia | 00866281 | 3 months to 17 years | Novartis |

| 2 | OL Phase I/II (Proof of Concept) Trial of midostaurin in AML and HR MDS with either wild-type or mutated FLT3 | 00977782 | ≥14 years | Novartis |

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; OL, open-label; DE, dose-escalating; S, safety; T, tolerability; PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics; R/R, relapsed or refractory; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HR, high-risk; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome.

Nilotinib is a second-generation TKI approved for imatinib-resistant Ph+ CML. The clinical trials in childhood leukemia are listed in Table 7. The first two trials in Table 7 correspond to studies 2 and 3 of those in the nilotinib PIP decision (Table 2). The first nilotinib PIP was submitted in 2008 and has so far been modified thrice (PIP number EMEA-000290-PIP01-08-M03). Modification number 3 was made in 2013. The first study in Table 7 is being performed in collaboration with the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). Both studies are still recruiting. The first study is planned to be concluded by 2020, the second by 2017, although the PIP decision asks for completion of all measures by September 2015. Table 7 also shows that nilotinib is presently being investigated in other, non-PIP-related clinical trials that include adolescents in Korea, India, the US, and Israel.

Table 7.

Nilotinib pediatric leukemia trials in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nilotinib in Ph+ CML children | 01844765 | 1–18 years | Novartis |

| 2 | PK of nilotinib in Ph+ CML or ALL children | 01077544 | 1–18 years | Novartis |

| 3 | Nilotinib and imatinib in ALL or CLL after donor SCT | 00702403 | ? | Fred Hutchinson CRC |

| 4 | Nilotinib and combination CT in newly-diagnosed ALL | 00844298 | ≥15 years | AMC, Korea |

| 5 | h–Igf-1 axis in CML children in remission | 01901666 | ? | PIMER, India |

| 6 | Nilotinib vs imatinib in CML | 00760877 | ≥17 years | Novartis |

| 7 | CT + irradiation + PBSCT in AML or ALL respondent to a TKI | 00036738 | ≤70 years | Fred Hutchinson CRC |

| 8 | Nilotinib in CML Phase II study | 00129740 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 9 | Imatinib vs nilotinib in CML | 00802841 | ≥16 years | Novartis |

| 10 | Decision on imatinib vs other TKI in CML | 01762969 | ≥16 years | Rabin Medical Center |

Notes: One study (NCT0132170) tested pegylated interferon-alfa 2a in TKD-treated adolescents and adults; one study (NCT01460498) investigated azacytidine in MRD CML treated with a TKI. The TKIs were not part of the experimental investigation. Study NCT01698905 included only adult patients. The three studies were not included in the table.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; PK, pharmacokinetics; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphoblastic leukemia; SCT, stem cell transplantation; CRC, Cancer Research Center; CT, chemotherapy; AMC, Asian Medical Center; PIMER, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research; PBSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; MRD, minimal residual disease.

Ponatinib is a third-generation TKI for the treatment of CML and Ph+ ALL that was FDA-approved in 2014 for adults with Ph+ leukemia resistant to other TKIs.2 The authors were unable to find any pediatric leukemia trials currently being performed with ponatinib. The PIP decision is from 2012, and the requested clinical trial should be finalized in 2020 (Table 2).

Volasertib is an inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1 that regulates numerous stages of mitosis and is overexpressed in many cancer types. Volasertib is presently in Phase III clinical trials in adult AML. So far, it is neither FDA- nor EMA-approved.30 Volasertib was tested by the US-based Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP), which concluded that volasertib showed potent in vitro activity against PPTP cell lines with no histotype selectivity and in vivo induced regressions in several xenograft models.

However, pharmacokinetic data suggest that mice tolerate higher systemic exposure to volasertib than humans, suggesting that the current results may over-estimate potential clinical efficacy against the childhood cancers studied.31

There is one volasertib pediatric leukemia clinical trial being performed (Table 8) which corresponds to the first PIP trial in Table 2. The trial is listed as “active, not recruiting”. The trial with 40 pediatric patients is planned to be completed in 2016. The PIP was submitted in 2011. PIP number EMEA-000674-PIP02-11 shows that this was the result of a second PIP negotiation round (PIP02), as opposed to all other PIPs documented in Table 1 that were agreed upon after the first round (PIP01). All volasertib PIP trials are expected to be finalized by 2023 (Table 2). There are numerous adult clinical trials listed in clinicaltrials.gov. The PPTP assessment of this compound raises ethical and scientific questions about whether children should be recruited into volasertib clinical trials before clinical efficacy in adults has been shown or instead into studies of agents with more promise in children are completed.

Table 8.

Volasertib pediatric leukemia trials in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Open-label dose-escalating trial to determine the MTD-advanced cancers for whom no therapy is known | 01971476 | 2–17 years | Boehringer Ingelheim |

Notes: The search terms “volasertib leukemia children” rendered two hits. However, study NCT01721876 is in patients ≥65 years only. This study was not included in this table.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; MTD, maximum tolerated dose.

Vosaroxin is a quinolone derivative currently in clinical trials for R/R AML and ovarian cancer.32 Vosaroxin failed to reach the primary endpoint in a study on R/R AML.33 Nevertheless, the primary clinical investigator insisted that the combination of vosaroxin and cytarabine was better than placebo plus cytarabine.34 As of July 26, 2015, there were no trials found in clinicaltrials.gov using the search terms “vosaroxin children leukemia”. The vosaroxin PIP trials should be finalized in July 2023. There are 13 adult trials in clinicaltrials.gov. The results reported by Levitan33 suggest that this is another example of a drug for which pediatric trials are scientifically and ethically questionable before better evidence of clinical efficacy in adults exists.

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cells (CAR T-cells) with CD19 specificity are a novel promising therapy for B-cell malignancies. CAR T-cells are patient-derived T-cells, transduced to express a chimeric antigen receptor, which includes an anti-CD19 antibody fragment fused to a T-cell intracellular signaling domain.2 Studies identified in clinicaltrials.gov using the search terms “autologous T-cells CD19 children leukemia” are listed in Table 9. Sponsors include centers around the world: in the US, UK, and People’s Republic of China. None of the studies in Table 9 are sponsored by the company that submitted the PIP shown in Table 2. Obviously, the CAR technology is already available to several clinical centers and collaborating universities. Should the sponsor get it approved as a drug, there will already be considerable pediatric experience, raising questions about what additional benefit the PIP studies will offer.

Table 9.

Pediatric leukemia trials with autologous T-cells against CD-19 in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A pediatric trial of genetically modified autologous T-cells directed against CD19 for R/CD19+ ALL | 01683279 | 1–26 years | Seattle Children’s Hospital |

| 2 | Redirected autologous T-cells engineered to contain humanized anti-CD19 in R/R CD19+ leukemia and lymphoma previously treated with cell therapy | 02374333 | 1–24 years | University of Pennsylvania |

| 3 | CART19 cells for patients with chemotherapy-resistant or chemotherapy-refractory CD19+ leukemia and lymphoma | 01626495 | 1–24 years | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia |

| 4 | Immunotherapy with CD19 CAR T-cells for CD19+ hematological malignancies | 02443831 | ≤24 years | University College London |

| 5 | Autologous T-lymphocytes genetically targeted to the B-cell specific antigen CD19 in pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed B-cell ALL | 01860937 | ≤26 years | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center |

| 6 | Anti-CD19 CAR-transduced T-cell therapy for patients with B-cell malignancies | 02456350 | 1–85 years | Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital, People’s Republic of China |

| 7 | T-cells or EBV-specific CTLs, advanced B-cell NHL and CLL | 00709033 | ? | Baylor College of Medicine |

| 8 | Treatment of relapsed and/or chemotherapy-refractory B-cell malignancy by CART19 | 01864889 | 5–90 years | Chinese PLA General Hospital |

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PLA, People’s Liberation Army; R/R, relapsed or refractory; EBV, epstein barr virus; CTL, cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Navitoclax is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of the B-Cell Lymphoma 2 (BCL2) protein. BCL2 is often overexpressed in hematologic malignancies and prevents apoptosis of malignant cells. Targeting BCL2 is a novel approach for various hematologic malignancies. Navitoclax is currently being investigated in adults with B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders but is not approved anywhere.35 Clinicaltrials. gov lists no pediatric leukemia studies. The two PIP studies should be finalized in 2019. While promising, it is unclear whether or which children should be included in navitoclax clinical trials before clinical efficacy in adults has been shown.

Blinatumomab is a CD19/CD3-bispecific T-cell-engaging antibody that binds to CD3 T-cells and co-localizes them with CD19+ B-cells, activates the T-cells, and induces death of these B-cells. Blinatumomab was FDA-approved in December 2014 for Philadelphia chromosome-negative R/R B-cell precursor ALL in adults.36 Four ongoing pediatric leukemia trials were found in clinicaltrials.gov (Table 10). Only the first trial in Table 10 is listed as recruiting. It is run by the NCI which plans to recruit 598 patients 1–30 years old by 2018. Two out of the three other clinical trials in clinicaltrials.gov correspond to PIP studies. The NCI has prioritized, moved rapidly, and already opened this large study in children, adolescents, and young adults. All other studies on relapsed B-ALL will compete with this high-priority study for patients.

Table 10.

Blinatumomab pediatric leukemia trials in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Risk-stratified randomized trial of blinatumomab in first relapse of childhood B-ALL | 02101853 | 1–30 years | NCI |

| 2 | Single-arm MC trial preceded by dose evaluation to investigate the E, S, and T of blinatumomab R/R B-precursor ALL | 01471782 | ≤17 years | Amgen Pharma |

| 3 | Phase III trial to investigate the E, S, and T of blinatumomab as consolidation therapy vs conventional consolidation CT HR first relapse B-precursor ALL | 02393859 | ≤17 years | Amgen Pharma |

| 4 | OL MC expanded access protocol for R/R B-precursor ALL | 02187354 | ≤17 years | Amgen Pharma |

Notes: The search term “blinatumomab leukemia children” resulted in five hits. However, study NCT02003222 was in ALL patients of 30–70 years. This study was not entered into this table.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NCI, National Cancer Institute; MC, multicenter; E, efficacy; S, safety; T, tolerability; R/R, relapsed or refractory; CT, chemotherapy; HR, high-risk; OL, open-label.

Dasatinib is a second-generation TKI that was FDA-approved in 2010 for newly-diagnosed adult Ph+ CML in the chronic phase. It is now also approved for CML and Ph+ ALL with resistance and intolerance to prior therapy, respectively. The studies listed in clinicaltrials.gov are shown in Table 11. The three Bristol Meyer Squibb-sponsored studies on R/R leukemia, pediatric CML, and Ph+ ALL corresponding to the three PIP studies listed in Table 3 are to be finalized in 2018. There are 18 other studies ongoing in Korea, Japan, India, the US, and Israel that include children and adolescents.

Table 11.

Dasatinib pediatric leukemia trials in http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dasatinib in R/R leukemia | 00306202 | 12 months to 20 years | BMS |

| 2 | Dasatinib in CML | 00777036 | ≤18 years | BMS |

| 3 | Dasatinib and CCT in ALL | 00720109 | 2–30 years | NCI |

| 4 | Dasatinib in malignancy not responding to imatinib | 00316953 | 1–21 years | NCI |

| 5 | Newly-diagnosed ALL | 00549848 | ≤18 years | St Jude CRH |

| 6 | Ph+ ALL | 01460160 | 1–17 years | BMS |

| 7 | Nilotinib in Ph+ CML | 01844765 | 1–18 years | Novartis |

| 8 | PK nilotinib in Ph+ CML or ALL | 01077544 | 1–18 years | Novartis |

| 9 | Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or intolerant CML | 00866736 | ≥15 years | Kanto CML Study Group |

| 10 | Ruxolitinib or dasatinib with CT in Ph-like ALL | 02420717 | ≥10 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 11 | Dasatinib in CML in Japan | 01464411 | ≥20 months | Kanto CML Study Group |

| 12 | Dasatinib in CML | 00254423 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 13 | Assessment of Gh–Igf-1 axis in CML in remission | 01901666 | ? | PIMER, India |

| 14 | CT + irradiation + PBSCT in ALL or CML responding to TKI | 00036738 | ≤70 years | Hutchinson CRC |

| 15 | Dasatinib stop trial in CML | 01627132 | ≥15 years | Shimousa HSG |

| 16 | Dasatinib + CT in adults with Ph+ ALL | 01004497 | 15–65 years | Catholic University of Korea |

| 17 | Dasatinib in CML or ALL | 00103701 | ≥14 years | BMS |

| 18 | Dasatinib in CML | 01887561 | ≥15 years | Kanto CML Study Group |

| 19 | Korean post-marketing surveillance of dasatinib | 01464047 | ? | BMS |

| 20 | IL-11 and dasatinib in CML | 00493181 | ? | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 21 | Pegasys in CML | 01392170 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 22 | Azacytidine in MRD CML | 01460498 | ≥16 years | MD Anderson Cancer Center |

| 23 | Treatment modification in CML | 01762969 | ≥16 years | Rabin Medical Center |

Notes: The listed studies were the result of the search terms “dasatinib children leukemia”, which resulted in 26 hits. Study NCT00364286 had only recruited adults; studies NCT00563290 and NCT00070499 recruited only patients ≥18 years old. These studies were not included in the table.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; R/R, relapsed or refractory; BMS, Bristol Meyer Squibb; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CCT, combination chemotherapy; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NCI, National Cancer Institute; CRH, Children Research Hospital; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive; PK, pharmacokinetics; CT, chemotherapy; PIMER, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research; PBSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CRC, Cancer Research Center; HSG, Hematology Study Group; IL-11, interleukin 11; MRD, minimal residual disease.

Imatinib was the first TKI, now also used for multiple cancers, including Ph+ CML, advanced gastrointestinal stroma tumor, R/R Ph+ ALL, and several forms of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative diseases. The FDA approved it in 2013 for children with Ph+ ALL. There are 66 pediatric leukemia trials listed in clinicaltrials.gov, reflecting the high interest present in the oncology community (Table 4), of which 40 studies are already completed, eight still recruiting, 13 active but not recruiting, and seven terminated. This is another example of how many, non-PIP proposed but competing studies are done in children when a promising drug is identified.

l-Asparaginase encapsulated in erythrocytes is a new galenic formulation of l-asparaginase, a well-established chemotherapeutic for adult and pediatric ALL.37 Table 12 shows the three clinicaltrials.gov trials that correspond to the three PIP trials listed in Table 3. The third of these studies is already completed, the first is “active, not recruiting”, and the second one is “available”. There is no doubt about the efficacy of l-asparaginase, but the requirements to measure its immunogenicity, its “pharmacodynamic activity”, and its “pharmacodynamic equivalence/comparative efficacy” in children are ethically questionable. Rare safety challenges are seldom detected in clinical trials, so a post-marketing safety observation study would appear to be more appropriate, since children enrolled in the PIP-proposed trials might not be available to enroll in other trials that offer greater chances of response or even cure.

Table 12.

Erythrocytes encapsulating l-asparaginase children leukemia

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GRASPA in relapsed ALL | 01518517 | 1–55 years | ERYtech Pharma |

| 2 | EAP: safety of GRASPA® with PCT in ALL patients <55 years at risk to receive other formulation of asparaginase | 02197650 | 1–55 years | ERYtech Pharma |

| 3 | GRASPA in relapsed ALL | 00723346 | 1–55 years | ERYtech Pharma |

Notes: The search term “erythrocytes l-asparaginase children leukemia” gave eight hits on July 21, 2015. Four of these studies used ordinary l-asparaginase (NCT00022737, NCT00070174, NCT00550992, NCT00458848) and were not included in the table. Furthermore, study NCT01910428 was in adults only and was also not included in this table.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; GRASPA, erythrocytes encapsulating l-asparaginase; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; EAP, Expanded Access Program; PCT, polychemotherapy.

Mercaptopurine is a well-known chemotherapeutic agent that is a standard part of many treatment schemes used in adult and pediatric leukemia. Clinicaltrials.gov lists 116 clinical trials in pediatric leukemia with mercaptopurine. A simple bioequivalence study for an oral suspension, compared to the tablet, performed in adults, makes sense.

Recombinant l-asparaginase is another l-asparaginase preparation. Table 13 shows that clinicaltrials.gov lists two trials, both of which are completed. Investigation of efficacy in two separate trials in children is ethically questionable, since the efficacy of l-asparaginase is well known. A safety assessment as part of a post-marketing observation would seem to be more appropriate.

Table 13.

Recombinant l-asparaginase children leukemia

| Number | Abbreviated title | NCT number | Age | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Comparative E and S of two asparaginase preparations in children with previously untreated ALL | 00784017 | 1–18 years | Medac Pharma |

| 2 | E and S of recombinant asparaginase in infants with previously untreated ALL | 00983138 | <1 year | Medac Pharma |

Notes: The search terms “recombinant l-asparaginase children leukemia” on July 21, 2015 gave six hits. However, four of these studies (NCT00720109, NCT02101853, NCT02003222, NCT02003222) did not use recombinant asparaginase.

Abbreviations: NCT, National Clinical Trial; E, efficacy; S, safety; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Discussion

An evaluation of the PIP decisions suggests that not all PDCO-mandated trials are practical to perform and some do not make sense scientifically or raise ethical concerns about possible exploitation of patients.

There are now several new TKIs. The high number of adult patients with Ph+ leukemias is obviously an incentive to develop further TKIs. But childhood leukemias are rare. Only 3%–4% of childhood ALL is Ph+, while in adults, it is 25%.38 CML exists in children, but it accounts for only 2%–3% of children with leukemia.39 The subfraction of Ph+ pediatric leukemia patients that are R/R to a first TKI is very small. Pediatric investigation of the second TKI was already initiated by the NCI but will take many years to recruit sufficient patients. Beginning simultaneous comparable trials for the next TKIs becomes questionable. Concerns about the one-size-fits-all logic of the AML standard PIP were confirmed by a review of the PIP decisions for bosutinib and ponatinib. For bosutinib, the PIP asks for a study on R/R CML resistant to prior TKI therapy, while for ponatinib, a study is requested in children with malignant diseases for which no effective treatment is known. If they are started at all, these PIP studies compete for recruitment with other, more reasonable studies.

There are several new formulations of chemotherapeutic agents, for example, l-asparaginase. There is in-depth research on how to better adapt treatment with l-asparaginase to the individual child’s genetic predisposition.40 We doubt that studies that investigate safety and “pharmacodynamic activity” of l-asparaginase in first relapsed ALL or comparison of the efficacy of two formulations of l-asparaginase (Table 3) are the best treatment options for these patients.

For several compounds, the PIP was negotiated early, and the studies were started years before proof of efficacy or safety in adults, or before studies that compared their efficacy with other new drugs were available, for example, midostaurin and volasertib.

Will it be ethical to initiate the navitoclax PIP studies? Children with R/R ALL leukemia are fighting for their lives, and many of them will die. Compounds with the greatest chances of improving survival should be studied first. This requires prioritization of drugs, studies, and of potential subjects. This cannot be done with a “standard PIP” approach. Forcing companies to “propose” studies that recruit these children into PDCO-dictated trials without such prioritization is a waste of industrial, regulatory, academic, and patient/parent resources and is not in the best interest of these children.

As the clinicaltrials.gov data shows, whenever a potential therapeutic benefit of a new compound is expected, clinical studies are opened worldwide in both adults and children. When additional PDCO-mandated trials are initiated (eg, R/R ALL), they compete for recruitment.

Once an innovative adult compound is approved anywhere and thus available, leukemia trials start in adults and children. There are 40 pediatric leukemia studies with imatinib completed, ten active but not recruiting, eight recruiting, and seven already terminated (Table 4). What relevance can the two additional imatinib PIP trials have? Other examples include dasatinib, nilotinib, and rituximab, where the PIP studies will consume resources and patients but are unlikely to have any significant impact.

The pediatric oncology community initially supported both US and EU pediatric legislation. They were frustrated to see that industry developed powerful new drugs against adult cancer, and felt themselves and their patients neglected.

The role of the EMA oncology PIP decisions is now increasingly discussed by academic pediatric oncologists. Adamson, for example, considers that for childhood cancer drug development, the most notable impact of the US and EU legislative initiatives has been the increasing engagement of the biopharmaceutical industry with investigators from academia in planning for pediatric drug development. He also describes how the PIP discussions at an early stage of development are, especially for Phase III trial plans, quite speculative. He identifies as the underlying cause that the discussion with the regulatory authorities is drug-centric and not disease-centric.41,42 Both Adamson and Vassal have expressed the wish that less waivers should be issued by the regulatory authorities.1,5,43 Vassal also observes that regulatory changes in the US and Europe have changed the environment for pediatric drug development, and addresses several unintended consequences, including the fact that legislation only causes adult cancer drugs to be studied in children, and that industry does not pursue first-in-children indications. He describes the futility of complex Phase III discussions at too early a point in development, that each drug is assessed independently, that too many PIPs are approved for the same indication, and that the feasibility of simultaneous drug trials in these rare-disease populations is disregarded. He proposes a modification of the PIP process specifically for anticancer drugs.2 Vassal et al explicitly called for oncology class waivers to be revoked.43

A new EMA class waiver decision was published in July 2015. The class waivers for a number of adult cancers, for example, liver and intra-hepatic bile duct carcinoma, were revoked. Furthermore, waivers for drug classes that target a number of cancers, including breast carcinoma and prostate carcinoma, have been revised.44,45 Obviously, EMA/PDCO want to expand the PIP system. The press release on this decision has the headline “Stimulating the development of medicines for children”.46 This is misleading. The EU pediatric regulation is not designed to develop drugs for children; it also makes drug development for adults more cumbersome. The review of the data outlined above suggests that a flawed approach could be expanded rather than improved.

The challenge of improving the treatment of children with leukemia appears at first glance to be a challenge of science. Science is a part of the challenge, but the challenge is more complex. The challenge is how to use the potential power of innovation to improve the treatment of childhood leukemia.

All players in drug development have their own conflicts of interests. Pediatric oncology institutions want bigger budgets and more publications, as well as access to potentially useful new treatments. Regulatory authorities want to justify their role as well as an expanded role in directing pharmaceutical drug development in public debate and opinion. Pharmaceutical companies are market-driven with clear business aims that involve return on investment.

Most specialists agree that steps toward the solution to these challenges (there are many types and subtypes of childhood leukemia) should come from biomedical research, but it is unclear whether or how this will come about. Perhaps, it will be possible to graft a CAR from a childhood leukemia patient onto a T-cell. Perhaps, computer programs will one day predict the direction(s) of mutations and preprogram the fitting of CARs. However, the authors disagree with Adamson and Vassal about the value of merely increasing engagement of biopharmaceutical industry in discussing childhood diseases, certainly not by the current EMA PIP process. The evidence presented suggests that the EMA’s leukemia decisions are not in the best interest of children. They impede rather than advance pediatric oncology research, could decrease public trust into pediatric clinical trials, and potentially, if not actually, cause harm to children. Forcing the pharmaceutical industry to enroll children into questionable studies prevents their recruitment into more useful studies. Increasing attention to pediatric oncology by expanding rather than improving the flawed PIP is not the same as finding better therapies.

The US approach offers a possible alternative. For example, blinatumomab was approved in the US at the end of 2014, while it is not yet licensed in the EU as of early August 2015. Once a compound like this is approved, it can be used in children off-label. And in fact, the US NCI has started a large blinatumomab clinical trial in first relapsed ALL. There is no counterpart to the US NCI in the EU. The Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer47 is an academic consortium. We would argue that one key element to help both adults and children with cancer is faster approval of effective drugs in adults and a prioritized, less globally redundant approach to pediatric studies that acknowledge the very limited number of available patients.

EMA/PDCO’s insistence on studies in ultrarare conditions has been discussed in other publications that focus on PDCO decisions related to metastasized melanoma. The frequency of pediatric patients with metastasized melanoma that need systemic treatment is ∼10% of what EMA/PDCO claims. There are now two international multicenter clinical trials recruiting adolescents with metastasized melanoma, and a warning has been published to ethics committees/institutional review boards worldwide to screen PDCO-triggered trials to prevent the abuse of children in unethical “ghost studies”.48–50 The term “therapeutic hostages” has been proposed to characterize this abuse, alluding to the term “therapeutic orphans” coined by Shirkey in 1963.48,51 The data presented here suggest similar concerns could be raised for children with R/R leukemia.

The questionable childhood leukemia PIP trials mentioned above have several potential adverse consequences. Recruitment into questionable studies prevents patients from enrolling in more meaningful studies, can create false hope in patients and parents, has the potential to destroy public confidence in pediatric clinical trials, and can cause companies that try to perform these studies to perform them in the developing world, as most US and (hopefully) also most EU centers will not participate.

Pediatric legislation is modifying the relationship between the major players in medicine and research. For many years, very few in clinical academia were involved with regulatory authorities or their decisions. This needs to change. Academic pediatric oncologists need to become more involved in analyzing regulatory decisions that affect their patients. PIP decisions and all trials listed in clinicaltrials. gov will have to be analyzed as will publications resulting from PIP-triggered trials to see if the concerns explained in this paper are confirmed. If so, it may be necessary for the cooperative groups involved in pediatric leukemia and oncology to take steps to try to improve or replace the current PIP system. Other stakeholders including industry, trade associations, parents, and support groups should also become more involved in assessing the impact of the PIP system on children with leukemia.

At present, there is insufficient incentive to develop truly new drugs targeted against childhood leukemia. A reward system is needed that appeals to a combination of several factors: science, skills in drug development from laboratory to the bedside, academic competition, financial greed, clinical empathy, personal or family concern, and a strong vision. For developing new treatments in childhood leukemia and other cancers, new thinking is needed. One possible model is the US Creating Hope Act that reward the first three companies that find a cure against a rare disease with a transferable voucher for priority review. The first such voucher was sold for ∼$US 68 Mio.1

Children cannot vote, so they are inadequately considered by legislators who approve biomedical research funding. Children with cancer are rare and therefore provide little promise of profits for the market-driven biopharmaceutical industry. Yet, the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act approach to provide financial incentives (in the form of prolonged market exclusivity) to study adult drugs in children was very effective. Clearly, financial incentives work in a market-driven system. Why not then create an incentive by offering reward for companies, institutions, or even individuals that reach drug development milestones for one of the many subgroups of childhood leukemia? Instead of creating a bureaucracy that chokes drug developers and potentially exploits or harms children, perhaps, the discussion should shift toward looking at ways to create mechanisms to reward market-driven pediatric oncology research.

Conclusion

The EMA/PDCO PIP process is not effectively helping children with leukemia and is not in their best interest. It should be redesigned to more closely match the FDA approach.

Drugs being developed for conditions that occur only in children should not involve the PDCO.

Drugs being developed for childhood leukemia (and other conditions both potentially lethal and extremely rare in children) should be prioritized so that the most promising drugs are studied first and only after sufficient evidence of efficacy and safety in adults.

Academic pediatric oncologists should take a more active role in reviewing and commenting on regulatory processes and decisions that affect their patients.

Incentives need to be developed that reward novel new approaches to drug development for pediatric leukemia and are consistent with the market forces that currently drive the biopharmaceutical industry.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

EMA/PDCO PIP decisions oncology

| Substance | Indication | PIP number | Decision year | Until | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aut T-Cells ag CD19 | CT-resistant CD19+ leukemia or lymphoma | EMEA-001654-PIP01-14 | 2015 | DEC 2021 | Leukemia |

| TH-302 | Ewing and soft tissue sarcoma | EMEA-001483-PIP01-13 | 2015 | DEC 2026 | Solid tumor |

| MK-8669,/AP23573 | Solid malignant tumors | EMEA-000458-PIP01-08 | 2010 | JUN 2019 | Solid tumor |

| HSV-TK gene | Operable supratentorial HGG | EMEA-000140-PIP01-07 | 2008 | 4y after ini | Solid tumor |

| MAB (MPDL3280A) | PD-L1 pos malignant neoplasms | EMEA-001638-PIP01-14 | 2015 | JUN 2015 | Solid tumor |