Abstract

Due to the high variance in available protocols on iodide-131 (131I) ablation in rodents, we set out to establish an effective method to generate a thyroid-ablated mouse model that allows the application of the sodium iodide symporter (NIS) as a reporter gene without interference with thyroidal NIS. We tested a range of 131I doses with and without prestimulation of thyroidal radioiodide uptake by a low-iodine diet and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) application. Efficacy of induction of hypothyroidism was tested by measurement of serum T4 concentrations, pituitary TSHβ and liver deiodinase type 1 (DIO1) mRNA expression, body weight analysis, and 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy. While 200 µCi (7.4 MBq) 131I alone was not sufficient to abolish thyroidal T4 production, 500 µCi (18.5 MBq) 131I combined with 1 week of a low-iodine diet decreased serum concentrations below the detection limit. However, the high 131I dose resulted in severe side effects. A combination of 1 week of a low-iodine diet followed by injection of bovine TSH before the application of 150 µCi (5.5 MBq) 131I decreased serum T4 concentrations below the detection limit and significantly increased pituitary TSHβ concentrations. The systemic effects of induced hypothyroidism were shown by growth arrest and a decrease in liver DIO1 expression below the detection limit. 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy revealed absence of thyroidal 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake in ablated mice. In summary, we report a revised protocol for radioiodide ablation of the thyroid gland in the mouse to generate an in vivo model that allows the study of thyroid hormone action using NIS as a reporter gene.

Key Words: Thyroid ablation, Hypothyroidism, Mouse model, Radioiodide

Introduction

Mouse models of hypothyroidism increase our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate thyroid hormone action both during normal function and disease. Drug-induced hypothyroidism is a commonly used approach for assessment of thyroid hormone action in rodent models. An alternative approach makes use of the thyroid-lethal properties of the radionuclide iodide-131 (131I) to induce hypothyroidism. This is based on the ability of thyroid follicular cells to transport and concentrate radioactive iodide due to their expression of the sodium iodide symporter (NIS). Several nonthyroidal organs physiologically express NIS, such as salivary glands, gastric mucosa and lactating mammary glands, and therefore possess the ability to actively transport iodide. They do not, however, organify and store it. These characteristics allow for high thyroid-specific cytotoxicity of 131I with minimal side effects [1].

The first report of selective destruction of thyroid tissue by 131I was published by Hamilton [2] in 1942. Since then, numerous protocols for radioiodide ablation of the mouse thyroid gland have been published with broad variation of the thyroid-lethal dose of 131I administered to mice ranging from 28 to 1,000 µCi (1-37 MBq) in the presence or absence of stimulation of thyroidal iodide uptake by treatment with a low-iodine diet (LID) for 1-4 weeks or exogenous thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) application prior to the administration of radioiodide [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

We and others have shown the potential of NIS as a reporter gene for molecular imaging with a broad range of possible applications [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In our previous work, the role of NIS as a reporter gene allowed noninvasive multimodal imaging of functional NIS expression by 99mTc or 123I scintigraphy as well as SPECT and 124I PET imaging that correlated well with the results of ex vivo gamma counter measurements as well as NIS mRNA and protein analysis. Stem cells have been the focus of research in gene and cellular therapies. To date, these studies have lacked detailed information about the exact in vivo biodistribution, survival and biological compartment of these cells in tissues. Genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells that express NIS allow detailed noninvasive in vivo tracking of stem cells from their initial deposition to survival, migration and differentiation by 123I scintigraphy/SPECT and 124I PET, as demonstrated in our previous work [17,18].

Based on these studies, we are now employing this system to study thyroid hormone action on mesenchymal stem cell biology within the tumor microenvironment. In an effort to generate a thyroid-ablated mouse model for the NIS-based evaluation of thyroid hormone action avoiding interference with thyroidal NIS that underlies an exclusive regulation by TSH, in the current study we describe an effective protocol for thyroid radioiodide ablation in mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male CD1 nu/nu mice from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with access to a standard nude mouse diet (2.2 mg/kg iodine; ssniff, Soest, Germany) or LID (<15 µg/kg iodine; ssniff) and tap water ad libitum. Animals were allowed to acclimatize for 1 week prior to the start of treatments. At the beginning of the experiments, mice weighed 25-30 g with an average body weight of 26.6 ± 1.27 g (mean ± SD). At the end of the experiments, animals were sacrificed and tissues and blood were taken for analysis. The experimental protocol was approved by the regional governmental commission for animals (Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany).

Thyroid Radioiodide Ablation

Mice were randomly assigned to different treatment groups. For thyroid ablation, animals received a single i.p. injection of 200 µCi (7.4 MBq; according to Kasuga et al. [10]; n = 6), 500 µCi (18.5 MBq; according to Gorbman [3]; n = 6) or 150 µCi (5.5 MBq; according to Abel et al. [11] and Barca-Mayo et al. [12]; n = 12) of carrier-free 131I in 250 µl of phosphate-buffered saline containing sodium thiosulfate as a reducing agent (GE Healthcare, Braunschweig, Germany) or saline for control animals (n = 6 for each experiment). Animals that received 500 µCi of 131I were additionally put on LID 1 week prior to radioiodide application. Before administration of the 150 µCi of 131I, mice were fed LID for 1 week and on day 8 received an i.p. injection of 10 mIU of bovine TSH (Sigma, Munich, Germany) 2 h before radioiodide application. A subset of radioiodide-ablated animals (n = 6) received daily i.p. injections of 20 ng/g body weight T4 (Sigma) starting the day after the application of 131I.

Serum T4 Measurements

T4 concentrations were monitored in pooled serum samples from tail vein blood or in individual serum samples after sacrifice. Serum total T4 concentrations were measured in duplicate by radioimmunoassay using a commercially available kit (RIA-4524; DRG Instruments, Marburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The samples and calibrators were incubated with radiolabelled tracer in antibody-coated tubes. After incubation, the liquid was aspirated and the antibody-bound radiolabelled tracer was counted in a gamma counter (1277 GammaMaster; LKB Wallac, Turku, Finland). The limit of quantification was at 10 nM with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 3.6% at 80 nM and 1.1% at 167 nM.

Whole-Body Planar 99mTc-Pertechnetate Scintigraphy

Two hours after i.p. injection of 500 µCi (18.5 MBq) of 99mTc-pertechnetate, a gamma emitter that is also transported by NIS [24], 99mTc-pertechnetate accumulation was assessed using a gamma camera equipped with a low-energy high-resolution collimator (e.cam, Siemens, Munich, Germany). Imaging studies were performed under inhalational anesthesia using an isoflurane vaporizer. Regions of interest were quantified and expressed as a fraction of the injected dose of applied radionuclide in the cervical region.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

After sacrifice, mouse pituitaries and livers were snap frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until further processing. Total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy Mini Kit with QIAshredder (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). Quantitative real-time PCR was run in duplicate with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) in a Mastercycler ep gradient S PCR cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Relative expression levels of pituitary TSHβ and liver deiodinase type 1 (DIO1) were calculated from ΔΔCt values normalized to internal β-actin and 18S rRNA. The following primers were used: Actb, forward 5′-AAGAGCTATGAGCTGCCTGA-3′, reverse 5′-TACGGATGTCAACGTCACAC-3′; R18s, forward 5′-CGCAGCTAGGAATAATGGAA-3′, reverse 5′-TCTGATCGTCTTCGAACCTC-3′; Tshb, forward 5′-GGGTATTGTATGACACGGGATA-3′, reverse 5′-ATTTCCACCGTTCTGTAGATGA-3′; Dio1, forward 5′-AAGACAGGGCTGAGTTTGGG-3′, reverse 5′-TGAGGAAATCGGCTGTGGAG-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Every data point was generated using 3-6 mice per group. Values are reported as means ± SEM or mean fold change ± SEM. Statistical significance of T4 and TSHβ concentrations were tested by two-tailed Student's t tests, and statistical significance of body weight measurements was tested by a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Results

131I Ablation and T4 Measurements

Three different protocols for radioiodide ablation of the thyroid gland were compared with the aim of establishing a thyroid-ablated mouse model of hypothyroidism. Four weeks after administration of a single dose of 200 µCi of 131I, serum T4 concentrations had dropped by 50% in ablated mice compared to untreated control animals (fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of radioiodide thyroid ablation protocols. a Serum T4 concentrations 4 weeks after injection of 200 µCi of 131I and 2 weeks after injection of 500 µCi of 131I combined with LID compared to untreated controls. The lower 131I dose resulted in a 50% reduction in serum T4 concentrations only, while the higher dose decreased T4 below the detection limit (<10 nM; *** p < 0.001). b Mice injected with 500 µCi of 131I suffered weight loss irrespective of T4 supplementation and had to be sacrificed, while untreated control mice showed continuous growth. Results are expressed as percent of initial body weight. c Serum T4 concentrations 2 and 10 weeks after treatment with LID/TSH/150 µCi 131I compared to untreated controls and mice that additionally received 20 ng/g body weight of T4. This treatment led to undetectable serum T4 concentrations as early as 2 weeks after 131I application, which remained undetectable after 10 weeks. T4-supplemented mice showed T4 concentrations in the range of the concentrations measured in untreated and therefore euthyroid control animals (* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001).

By increasing the 131I dose to 500 µCi with additional treatment with LID for 1 week prior to 131I application, serum T4 concentrations dropped below the limit of detection (<10 nM) as early as 2 weeks after radioiodide administration (fig. 1a). However, starting at approximately 1 week after ablation, mice suffered from drastic weight loss and heavy breathing despite T4 supplementation in a subgroup of mice, and, as a result, had to be sacrificed (fig. 1b).

The combination of 1 week of LID and stimulation with TSH prior to administration of 150 µCi of 131I (LID/TSH/150 µCi of 131I) resulted in serum T4 concentrations below the detection limit within 2 weeks after ablation that remained stable until the end of the observation period (10 weeks after ablation; fig. 1c). The ablated mice without T4 supplementation showed only minor side effects such as absence of weight gain (fig. 3) and slower movement in the cage. Therefore, all further experiments were conducted following this protocol. Serum T4 concentrations in the subgroup of mice that received T4 supplementation by daily i.p. injections of 20 ng of T4 per gram body weight were in the same range as in the untreated euthyroid group of mice (fig. 1c).

Fig. 3.

Body weight analysis. While control animals continued to grow throughout the observation period, LID/TSH/150 µCi 131I-treated mice showed growth arrest starting from around 1 week after thyroid ablation (day 0). Results are expressed as percent of initial body weight (** p < 0.01).

Monitoring of Body Weight and Analysis of TSHβ and DIO1 mRNA Expression

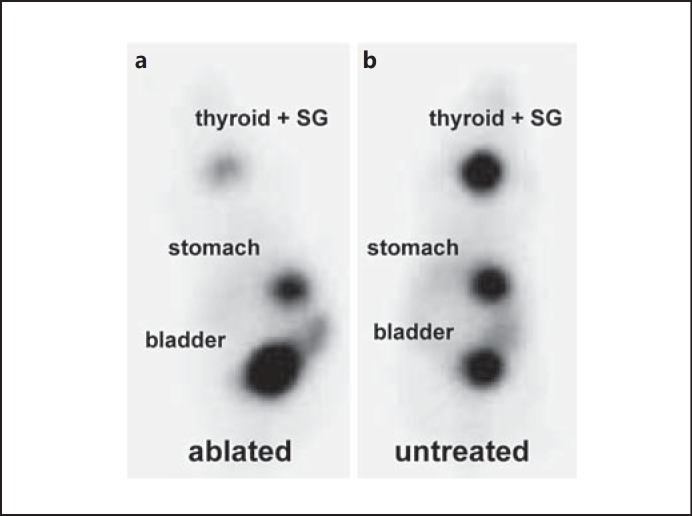

The drop in serum T4 concentrations in ablated mice coincided with a 48- and 45-fold increase, respectively, in pituitary TSHβ concentrations 2 and 10 weeks after thyroid ablation, compared to untreated controls (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pituitary TSHβ mRNA expression. 2 and 10 weeks after LID/TSH/150 µCi 131I treatment, pituitary TSHβ mRNA concentrations were increased significantly 48- and 45-fold, respectively, compared to untreated control mice (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). conc. = Concentration.

As a drop in serum T4 and elevation of pituitary TSH do not per se prove a systemic state of hypothyroidism, we additionally monitored body weight gain in ablated mice versus untreated control mice. Radioiodide-ablated mice showed an arrest in growth from around 1 week after 131I injection, while untreated control animals continued to grow throughout the observation period (fig. 3). We also investigated expression of DIO1 in the liver as a second marker for systemic hypothyroidism. Four weeks after 131I application, liver DIO1 mRNA concentrations dropped below the detection limit with Ct values >40, whereas for control animals a mean Ct value of 26.11 ± 0.69 was measured with comparable reference gene concentrations between the two treatment groups.

99mTc-Pertechnetate Whole-Body Imaging

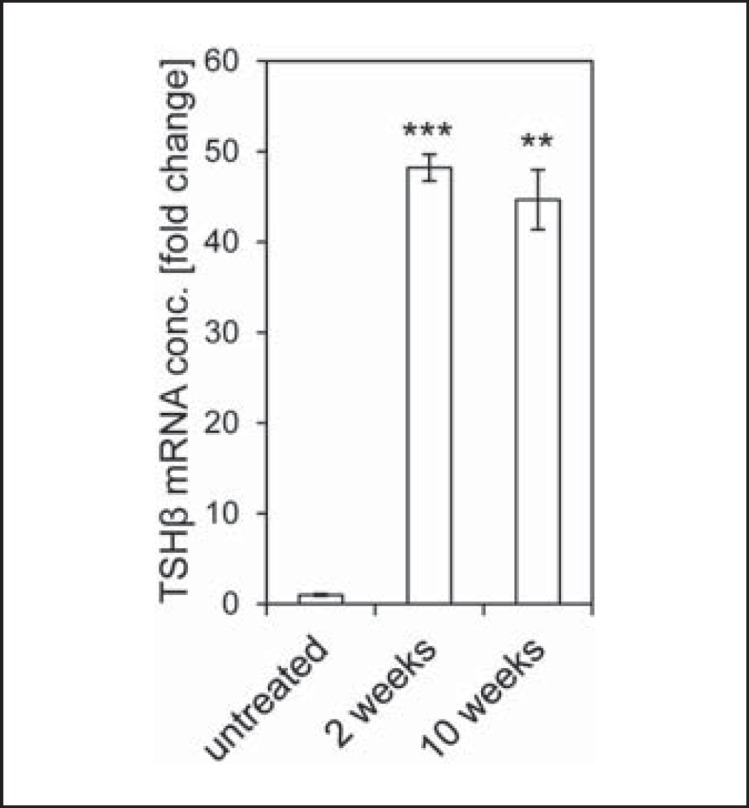

To examine the effects of 131I ablation on thyroidal radioiodide uptake, we monitored 99mTc-pertechnetate biodistribution by gamma camera imaging. Significant 99mTc-pertechnetate accumulation was observed in tissues that physiologically express NIS, i.e. thyroid, salivary glands and stomach, as well as the urinary bladder due to renal elimination of the radionuclide (fig. 4). Four weeks after 131I injection, 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake was strongly reduced in the cervical region of ablated mice with a remaining 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake of approximately 3-5%, which was caused by the salivary glands that in mice are localized in the direct neighborhood of the thyroid gland and physiologically express NIS (fig. 4a) [25]. In comparison, untreated control mice accumulated approximately 35-40% of the injected dose in the cervical region (fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Whole-body 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy. 4 weeks after LID/TSH/150 µCi 131I treatment, 99mTc-pertechnetate gamma camera imaging showed strongly reduced 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake in the neck region of ablated animals (approx. 3-5 %; a) compared to untreated control animals (b). A representative image for both ablated mice and control mice is shown. SG = Salivary glands.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to generate a mouse model in which endogenous thyroid hormone production is abolished to create an experimental paradigm with a defined baseline for the evaluation of response to thyroid hormone that at the same time allows for the use of NIS as a reporter gene. While treatment of mice with antithyroid drugs in drinking water is a widely used approach to render mice hypothyroid, mice have to be treated throughout the experiment, a certain degree of variability remains due to differences in water intake and potential side effects of the drugs have to be taken into consideration [26,27]. Furthermore, as this approach typically relies on a combination of thioamides (methimazole or propylthiouracil) that have been shown to affect thyroidal NIS expression [28], as well as the NIS-specific inhibitor perchlorate to block thyroid hormone synthesis, the use of NIS as a reporter gene to study thyroid hormone action is limited in this setting.

For these reasons, a reliable method of thyroid radioiodide ablation was developed in mice that exploits the ability of NIS to transport 131I. This eliminates interference of reporter gene activity from thyroidal NIS that is exclusively regulated by TSH and therefore affected by the thyroid hormone status of the mouse. A literature search revealed a variety of protocols [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. As the ‘American Thyroid Association Guide to investigating thyroid hormone economy and action in rodent and cell models' [29] had just been published, we initially tested the protocol described there [10]. Here the recommended 131I dose of 200 µCi was not sufficient to completely abolish endogenous thyroid hormone production. This was most likely due to insufficient accumulation of radioiodide in the thyroid, as mice were fed standard chow containing 2.2 mg/kg iodine, which competes with radioiodide for thyroidal uptake. We therefore increased the amount of 131I to 500 µCi, a dose that was reported by Gorbman [3] to destroy thyroid tissue within 24 days after radioiodide application. In addition, we pretreated mice with LID for 1 week prior to 131I application to decrease thyroidal iodine content and increase thyroidal NIS expression to enhance the uptake of radioiodide into thyroid follicular cells. This treatment decreased serum T4 concentrations below the detection limit. However, mice showed severe side effects, i.e. drastic weight loss and breathing difficulties, starting from around 1 week after iodide injection irrespective of T4 supplementation, and had to be sacrificed prematurely. We assume that the relatively high dose of 131I, while specifically concentrated in the thyroid, caused severe damage to the thyroid-surrounding tissues, in particular the radiation-sensitive trachea. Due to the close proximity of these tissues to the thyroid and the thyroid's small size, the β-particles emitted by 131I that have a path length of up to 2.4 mm in tissue [30] can cause lesions in the trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands, as was observed by Gorbman [4]. Furthermore, transient NIS-mediated transport of high doses of radioiodide across epithelia in the gastrointestinal tract may impair their function and lead to subsequent damage.

To avoid the aforementioned problems, we adapted protocols published by Abel et al. [11] and Barca-Mayo et al. [12], where relatively low doses of 131I were reported to be sufficient for total ablation of the thyroid gland under stimulation of 131I uptake. We decided on a protocol consisting of 1 week of LID, followed by an injection of bovine TSH on day 8, 2 h before injection of 150 µCi of 131I. We showed the efficacy of this protocol in inducing hypothyroidism in mice at the level of (1) the first indicators of a disruption of thyroid function, i.e. serum T4 concentrations and pituitary TSHβ content, (2) indicators of systemic hypothyroidism, i.e. growth arrest and decrease in liver DIO1 concentrations, and (3) the thyroid itself by 99mTc-pertechnetate gamma camera imaging.

Two weeks after thyroid ablation, serum T4 concentrations had dropped below the detection limit and, as expected, pituitary TSHβ concentrations reactively increased 48-fold compared to untreated control mice. At the end of the observation period, 10 weeks after thyroid ablation, T4 concentrations remained undetectable and TSHβ concentrations remained high. As growth hormone secretion is thyroid hormone sensitive in rodents [31], ablated mice showed an arrest in growth as a consequence of decreasing serum thyroid hormone concentrations, indicating systemic hypothyroidism. Another marker for systemic thyroid hormone status is liver DIO1, which is downregulated in hypothyroidism [32]. Four weeks after thyroid ablation, liver DIO1 mRNA concentrations had dropped below the detection limit. Gamma camera imaging revealed a significant reduction in 99mTc-pertechnetate uptake in the cervical region 4 weeks after thyroid ablation, despite maximal TSH stimulation due to thyroid hormone deficiency in ablated animals. The low residual uptake originates from salivary glands that also physiologically express NIS [25,33]. In mice, the submandibular-sublingual salivary gland complex is relatively large in relation to the thyroid and is located in the ventral cervical region in the direct neighborhood of the thyroid, therefore causing an overlapping signal on 123I or 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphies [34]. As salivary glands do not possess the ability to organify iodine, retention time of the thyroid-ablative dose of 131I is limited. Thus, salivary glands are preserved, at least in part, as is their ability to accumulate 99mTc-pertechnetate, while thyroidal uptake is completely eliminated, as was shown by whole-body and neck transaxial planar SPECT imaging by Choi et al. [35].

In conclusion, our data provide an effective protocol for radioiodide ablation of the thyroid gland that renders mice hypothyroid within the course of 2 weeks and abolishes thyroidal radioiodide uptake. Based on our findings, we recommend stimulation of NIS-mediated thyroidal iodide uptake by pretreatment with LID and TSH application to help deliver a well-tolerated dose of 150 µCi of 131I to mice for successful ablation of the thyroid gland.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to E.K. Wirth, Institut für Experimentelle Endokrinologie, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Berlin, Germany), for providing TSHβ primer sequences and J. Carlsen and R. Oos, Department of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital of Munich (Munich, Germany), for their assistance with animal care. This study was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the Priority Programme SPP1629 to C. Spitzweg and P.J. Nelson (SP 581/6-1), H. Heuer (HE 3418/7-1) and J. Köhrle (KO 922/17-1).

References

- 1.Spitzweg C, Morris JC. The sodium iodide symporter: its pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57:559–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton JG. The use of radioactive tracers in biology and medicine. Radiology. 1942;39:541–572. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbman A. Effects of radiotoxic dosages of I131 upon thyroid and contiguous tissues in mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1947;66:212–213. doi: 10.3181/00379727-66-16040p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorbman A. Functional and structural changes consequent to high dosages of radioactive iodine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1950;10:1177–1191. doi: 10.1210/jcem-10-10-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sloviter HA. The effect of complete ablation of thyroid tissue by radioactive iodine on the survival of tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 1951;11:447–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberberg R, Silberberg M. Skeletal effects of radio-iodine induced thyroid deficiency in mice as influenced by sex, age and strain. Am J Anat. 1954;95:263–289. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000950205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar MS, Chiang T, Deodhar SD. Enhancing effect of thyroxine on tumor growth and metastases in syngeneic mouse tumor systems. Cancer Res. 1979;39:3515–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross DS, Downing MF, Chin WW, Kieffer JD, Ridgway EC. Divergent changes in murine pituitary concentration of free alpha- and thyrotropin beta-subunits in hypothyroidism and after thyroxine administration. Endocrinology. 1983;112:187–193. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-1-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shupnik MA, Chin WW, Ross DS, Downing MF, Habener JF, Ridgway EC. Regulation by thyroxine of the mRNA encoding the alpha subunit of mouse thyrotropin. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:15120–15124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasuga Y, Matsubayashi S, Sakatsume Y, Akasu F, Jamieson C, Volpé R. The effect of xenotransplantation of human thyroid tissue following radioactive iodine-induced thyroid ablation on thyroid function in the nude mouse. Clin Invest Med. 1991;14:277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abel ED, Boers ME, Pazos-Moura C, Moura E, Kaulbach H, Zakaria M, Lowell B, Radovick S, Liberman MC, Wondisford F. Divergent roles for thyroid hormone receptor beta isoforms in the endocrine axis and auditory system. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:291–300. doi: 10.1172/JCI6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barca-Mayo O, Liao XH, DiCosmo C, Dumitrescu A, Moreno-Vinasco L, Wade MS, Sammani S, Mirzapoiazova T, Garcia JG, Refetoff S, Weiss RE. Role of type 2 deiodinase in response to acute lung injury (ALI) in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1321–E1329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109926108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klutz K, Russ V, Willhauck MJ, Wunderlich N, Zach C, Gildehaus FJ, Göke B, Wagner E, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Targeted radioiodine therapy of neuroblastoma tumors following systemic nonviral delivery of the sodium iodide symporter gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6079–6086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klutz K, Schaffert D, Willhauck MJ, Grünwald GK, Haase R, Wunderlich N, Zach C, Gildehaus FJ, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Göke B, Wagner E, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted (131)I-therapy of liver cancer following systemic delivery of the sodium iodide symporter gene. Mol Ther. 2011;19:676–685. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Wunderlich N, Zach C, Anton M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Göke B, Spitzweg C. Sodium iodide symporter (NIS)-mediated radionuclide ((131)I, (188)Re) therapy of liver cancer after transcriptionally targeted intratumoral in vivo NIS gene delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:1403–1412. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Dohmen C, Wunderlich N, Knoop K, Zach C, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Gildehaus FJ, Ziegler S, Fürst S, Göke B, Wagner E, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Image-guided tumor-selective radioiodine therapy of liver cancer after systemic nonviral delivery of the sodium iodide symporter gene. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:1563–1574. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knoop K, Kolokythas M, Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Wunderlich N, Draganovici D, Zach C, Gildehaus FJ, Böning G, Göke B, Wagner E, Nelson PJ, Spitzweg C. Image-guided, tumor stroma-targeted 131I therapy of hepatocellular cancer after systemic mesenchymal stem cell-mediated NIS gene delivery. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1704–1713. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knoop K, Schwenk N, Dolp P, Willhauck MJ, Zischek C, Zach C, Hacker M, Göke B, Wagner E, Nelson PJ, Spitzweg C. Stromal targeting of sodium iodide symporter using mesenchymal stem cells allows enhanced imaging and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Gene Ther. 2013;24:306–316. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grünwald GK, Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Schwenk N, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Schwaiger M, Zach C, Göke B, Holm PS, Spitzweg C. Sodium iodide symporter (NIS)-mediated radiovirotherapy of hepatocellular cancer using a conditionally replicating adenovirus. Gene Ther. 2013;20:625–633. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grünwald GK, Vetter A, Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Schwenk N, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Schwaiger M, Zach C, Wagner E, Göke B, Holm PS, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Systemic image-guided liver cancer radiovirotherapy using dendrimer-coated adenovirus encoding the sodium iodide symporter as theranostic gene. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1450–1457. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.115493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grünwald GK, Vetter A, Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Schwenk N, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Schwaiger M, Zach C, Wagner E, Göke B, Holm PS, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. EGFR-targeted adenovirus dendrimer coating for improved systemic delivery of the theranostic NIS gene. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e131. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trujillo MA, Oneal MJ, McDonough S, Qin R, Morris JC. A probasin promoter, conditionally replicating adenovirus that expresses the sodium iodide symporter (NIS) for radiovirotherapy of prostate cancer. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baril P, Martin-Duque P, Vassaux G. Visualization of gene expression in the live subject using the Na/I symporter as a reporter gene: applications in biotherapy. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penheiter AR, Russell SJ, Carlson SK. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) as an imaging reporter for gene, viral, and cell-based therapies. Curr Gene Ther. 2012;12:33–47. doi: 10.2174/156652312799789235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzweg C, Joba W, Schriever K, Goellner JR, Morris JC, Heufelder AE. Analysis of human sodium iodide symporter immunoreactivity in human exocrine glands. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4178–4184. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandyopadhyay U, Biswas K, Banerjee RK. Extrathyroidal actions of antithyroid thionamides. Toxicol Lett. 2002;128:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cano-Europa E, Blas-Valdivia V, Franco-Colin M, Gallardo-Casas CA, Ortiz-Butrón R. Methimazole-induced hypothyroidism causes cellular damage in the spleen, heart, liver, lung and kidney. Acta Histochem. 2011;113:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitzweg C, Joba W, Morris JC, Heufelder AE. Regulation of sodium iodide symporter gene expression in FRTL-5 rat thyroid cells. Thyroid. 1999;9:821–830. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianco AC, Anderson G, Forrest D, Galton VA, Gereben B, Kim BW, Kopp PA, Liao XH, Obregon MJ, Peeters RP, Refetoff S, Sharlin DS, Simonides WS, Weiss RE, Williams GR. American Thyroid Association Guide to investigating thyroid hormone economy and action in rodent and cell models. Thyroid. 2014;24:88–168. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dingli D, Diaz RM, Bergert ER, O'Connor MK, Morris JC, Russell SJ. Genetically targeted radiotherapy for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102:489–496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hervas F, Morreale de Escobar G, Escobar Del Rey F. Rapid effects of single small doses of L-thyroxine and triiodo-L-thyronine on growth hormone, as studied in the rat by radioimmunoassy. Endocrinology. 1975;97:91–101. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-1-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zavacki AM, Ying H, Christoffolete MA, Aerts G, So E, Harney JW, Cheng SY, Larsen PR, Bianco AC. Type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase is a sensitive marker of peripheral thyroid status in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1568–1575. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonica F, Kasprzyk DF, Opitz R, Iacovino M, Liao XH, Dumitrescu AM, Refetoff S, Peremans K, Manto M, Kyba M, Costagliola S. Generation of functional thyroid from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2012;491:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nature11525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boschi F, Pagliazzi M, Rossi B, Cecchini MP, Gorgoni G, Salgarello M, Spinelli AE. Small-animal radionuclide luminescence imaging of thyroid and salivary glands with Tc99m-pertechnetate. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:76005. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.7.076005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi JS, Park IS, Kim SK, Lim JY, Kim YM. Morphometric and functional changes of salivary gland dysfunction after radioactive iodine ablation in a murine model. Thyroid. 2013;23:1445–1451. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]