Abstract

Cerebral infarction (CI) is a crucial complication of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) associated with poor clinical outcome. We aimed at developing an early risk score for CI based on clinical characteristics available at the onset of SAH. Out of a database containing 632 consecutive patients with SAH admitted to our institution from January 2005 to December 2012, computed tomography (CT) scans up to day 42 after ictus were evaluated for CIs. Different parameters from admission up to aneurysm treatment were collected with subsequent construction of a risk score. Seven clinical characteristics were independently associated with CI and included in the Risk score (BEHAVIOR Score, 0 to 11 points): Blood on CT scan according to Fisher grade ⩾3 (1 point), Elderly patients (age ⩾55 years, 1 point), Hunt&Hess grade ⩾4 (1 point), Acute hydrocephalus requiring external liquor drainage (1 point), Vasospasm on initial angiogram (3 points), Intracranial pressure elevation >20 mm Hg (3 points), and treatment of multiple aneurysms (‘Overtreatment', 1 point). The BEHAVIOR score showed high diagnostic accuracy with respect to the absolute risk for CI (area under curve=0.806, P<0.0001) and prediction of poor clinical outcome at discharge (P<0.0001) and after 6 months (P=0.0002). Further validation in other SAH cohorts is recommended.

Keywords: cerebral infarct, outcome, prediction, risk score, subarachnoid hemorrhage

Introduction

Cerebral infarction (CI) is known to be a major cause of poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).1, 2, 3, 4 Rates of CI visible on computed tomography (CT) follow-up scans range between 21% and 65%5, 6, 7 and is even higher with magnetic resonance imaging, reaching up to 81%.8, 9

Many predictors of CI have been already reported, frequently with conflicting results: amount of intracranial hemorrhage,1, 6, 10 angiographic vasospasm,7, 11, 12 aneurysm location7 and size,3 impaired initial clinical condition,1, 3, 6 higher patient' age,3 history of diabetes,3, 9 hyperglycemia,3, 10 history of hypertension,3 early hydrocephalus,9 requirement of external liquor drain,9 global cerebral edema,1 nocturnal occurrence of SAH,6 high body mass index,6 febrile temperature,3 and systemic inflammation.13 However, a cumulative analysis of major predictors for CI allowing the assessment of CI probability for the individual patient is still lacking.

The goal of this study was to develop a risk score for early identification of individuals at high risk for CI using clinical characteristics available at the onset of SAH. Furthermore, the ability of this score to predict clinical outcome of SAH was analyzed.

Materials and methods

We analyzed data from a patient database containing 674 consecutive patients admitted to the University Hospital of Freiburg with spontaneous SAH between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2012. Inclusion criteria were hospital admission with aneurysmal SAH within 72 hours after clinical onset and at least one follow-up CT scan. Collection of patient data and further investigations were performed after the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee (Ethik-Kommission, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Registration number: 446/13) and according to its ethical standards on human studies. All persons or their relatives gave their informed consent within the written treatment contract signed on admission to our institution. The study was registered in the German clinical trial register (DRKS, Unique identifier: DRKS00005486).

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Management

All patients were initially admitted to the neurocritical care unit. Our SAH management policy has been described in more detail previously.14, 15 Here, we focus on essential aspects.

The bleeding cause was identified within 24 hours after admission. In all, 85% of the cohort underwent digital subtraction angiography (DSA) for diagnostic purposes. In the remaining cases (due to the need for urgent surgery or recently modified diagnostic algorithm), the patients underwent only CT angiography before aneurysm securing. The treatment decision was made after interdisciplinary assessment.

Repeated CT scans were performed: (1) routinely for all patients after aneurysm treatment; (2) selectively in cases with new neurologic deficits or a prolonged state of impaired consciousness.

Acute hydrocephalus after SAH was treated with external ventricular drainage (EVD) allowing continuous monitoring of intracranial pressure (ICP). According to the house regulations, the cutoff for pathologic ICP elevation was set at 20 mm Hg. The patients with good initial condition and benign clinical course who did not require EVD were considered not to have pathologic ICP elevations.16

Any sustained ICP elevation requiring additional ICP management (conservative/surgical) in the time frame from EVD placement up to the patients' return to our ICU after the aneurysm treatment was included into the risk score.

Data Management

We collected demographic (age, gender), historical (preexisting morbidity), and laboratory (leukocytes, hemoglobin, pH, and blood glucose on admission) data in the database. Only parameters available from patients' admission up to the aneurysm treatment were included for further statistical analyses and recorded in a unique database (Microsoft Access 2010, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Clinical grade on admission was assessed according to Hunt and Hess,17 clinical follow-up at discharge and after 6 months (±3 months) was evaluated using the mRS (modified Rankin scale).18 Hunt and Hess grade was dichotomized into good (1 to 3) and poor (4 and 5) grade, mRS score at discharge into favorable (1 to 3) and unfavorable (4 to 6) outcome, with special attention to in-hospital mortality. The mRS score at 6 months was assessed based on clinical information from repetitive hospital stays for control angiography and/or shunt controls, the missing values (42 cases) were replaced using multiple imputation. Any improvement in mRS score since discharge up to the 6 month' follow-up was defined as clinical improvement.

Cerebral infarction was defined as one or more new hypodense abnormalities on CT scan within 6 weeks after SAH. Hypodensities on CT imaging resulting from intracerebral hemorrhage, surgical approach or EVD were excluded. All follow-up CT scans up to 6 weeks after SAH were reviewed by the first author (RJ) blinded at this time for any clinical information.

The severity of subarachnoid bleeding was classified on the initial CT imaging according to Fisher et al19 with dichotomization into low (1 or 2) and high (3 or 4) grades. In addition, intraventricular hemorrhage was documented in a dichotomized manner (present/absent), as well as quantitatively analyzed using the original Graeb score.20 If intracerebral hemorrhage was present, then its location and volume according to the formula AxBxC/2 (ref. 21) was recorded.

Angiographic imaging at admission was evaluated with regard to aneurysm characteristics: the number of aneurysms, as well as the size and morphology of the treated aneurysm(s). The presence of an unequivocal narrowing of the arterial vessel lumen on DSA on admission7 was defined as ‘early angiographic vasospasm'.

Finally, the treatment modalities including the treatment of multiple aneurysms and treatment complications were recorded.

Statistical Analysis and Design of the Scoring System

Data analysis was performed with the use of PRISM (version 5.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS (version 21, SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software.

Continuous variables were dichotomized at the mean values (age, aneurysm size, extent of ICH and intraventricular hemorrhage) or at abnormality cutoffs (laboratory parameters). Differences with a P-value of 0.05 or less were considered as statistically significant. Univariate analysis was performed using Fisher exact test. Afterwards, significant variables were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to define independent infarct predictors. Missing data (1.27% for radiographic variables from initial CT scan, 15.2% for ‘early angiographic vasospasm', 9.34% for ‘aneurysm morphology' and ‘aneurysm size', and 15.66% for ‘admission blood glucose' and ‘admission pH values') were replaced using multiple imputation method in SPSS (upon Monte Carlo Markov chain algorithm known as fully conditional specification or chained equations imputation).

Finally, significant predictors from multivariate analysis were used for the development of the infarct risk score as follows: the odds ratios were divided by the smallest coefficient and then rounded to the nearest whole number. Based upon the presence of these risk factors, each patient was assigned a total point value.

The created infarct risk score passed through internal validation using ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test for goodness of fit for logistic regression models and the bootstrapping method that is now widely regarded as a better validation approach than data splitting.22 Furthermore, bootstrapping is recommended to gain insight into the likelihood of the model missing important variables, being overfitted or unstable and known to be a fair replacement tool for external validation.23 Then, the new risk score was compared with Hunt&Hess and original Fisher score with regard to the diagnostic accuracy by means of ROC curves. Finally, the risk score was correlated with CI probability and clinical outcome measurements using linear regression analysis.

Results

Of the 674 consecutive patients with acute aneurysmal SAH, 632 patients met all inclusion criteria. The mean age of patients was 55.1 years (range 21 to 94 years) and 401 of them (63%) were female. Sixty percent of patients were treated with endovascular coiling. In all, 254 of 632 patients (40%) had a favorable outcome at discharge; the in-hospital mortality rate was 19%. The more detailed information on population characteristics is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographic, clinical, and radiologic characteristics of the patients in regard to CI occurrence.

| Parameter |

n (%), or mean (±standard deviation) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No infarction | CI present | |

| Number of cases, n | 312 (49%) | 320 (51%) |

| Age, years | 53.3 (±13.5) | 56.9 (±13.2) |

| Sex (women), n | 190 (60.9%) | 211 (65.9%) |

| Poor Hunt & Hess grade (4–5), n | 58 (18.6%) | 167 (52.2%) |

| Fisher grade (3–4), n | 225 (72.1%) | 294 (91.9%) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage, n | 61 (19.6%) | 102 (31.9%) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, n | 68 (21.8%) | 140 (43.8%) |

| Time to treatmenta, h | 16 (±14) | 18.9 (±35.3) |

| Treatment modality (coiling), n | 198 (63.5%) | 199 (62.2%) |

| Location of ruptured aneurysm (anterior circulation), n | 267 (85.6%) | 269 (84.1%) |

| Aneurysm morphology (fusiform), n | 11 (3.5%) | 12 (3.8%) |

Abbreviations: CI, cerebral infarction; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage. The baseline data presented in this table have been partially reported in a previous publication16 dealing with different aspects of our institution's SAH database.

Since the admission.

Predictors of Cerebral Infarction on Computed Tomography Scans and Derivation of the BEHAVIOR Score

CI was documented in 320 patients (51%) on 3,070 CT scans performed within 6 weeks after ictus. From a broad list of factors potentially influencing the occurrence of CI (see the results of the univariate analysis under Supplementary materials, available online), seven variables remained significant when analyzed with multivariate logistic regression analysis and were therefore included to the BEHAVIOR risk score (Table 2). Based on their proportional contribution, the following points were attributed to these predictors: three points each for early angiographic vasospasm and pathologic ICP elevation and one point each for higher age, higher Hunt & Hess and/or Fisher grades, treatment of multiple aneurysms and the need for EVD. Accordingly, the CI risk score ranged from 0 to 11 points (Table 2). The mean risk score value was 3.5 points (±2.3). In all, 596 patients (94%) had at least 1 risk factor, 1 patient scored the possible maximum of 11 points.

Table 2. Multivariate statistical analysis of significant predictors for cerebral infarction and corresponding weights for BEHAVIORa score.

| Parameter | OR (95% confidence interval) | P-value | Score weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early vasospasm on DSA | 6.19 (2.66–14.45) | <0.0001 | 3 |

| ICP elevation>20 mm Hg | 6.60 (3.54–12.32) | <0.0001 | 3 |

| Age (⩾55 years old) | 2.19 (1.44–3.33) | <0.0001 | 1 |

| Treatment of multiple aneurysms | 1.95 (1.05–3.63) | 0.034 | 1 |

| Fisher grade (3–4) | 2.15 (1.21–3.83) | 0.009 | 1 |

| Hunt & Hess grade (4–5) | 2.01 (1.22–3.33) | 0.007 | 1 |

| Need for EVD | 1.84 (1.18–2.85) | 0.007 | 1 |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; EVD, external ventricular drainage; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; ICP, intracranial pressure; OR, odds ratio.

The created score was named ‘BEHAVIOR' as acronym for the included predictors: ‘B' (Blood on CT) for higher Fisher grade, ‘E' (Elderly) for higher age, ‘H' for higher Hunt & Hess, ‘A' (Acute hydrocephalus) for need for EVD, ‘V' for early angiographic Vasospasm, ‘I' for pathologic ICP, ‘O' (Overtreatment) for treatment of multiple aneurysms, ‘R' for Risk score.

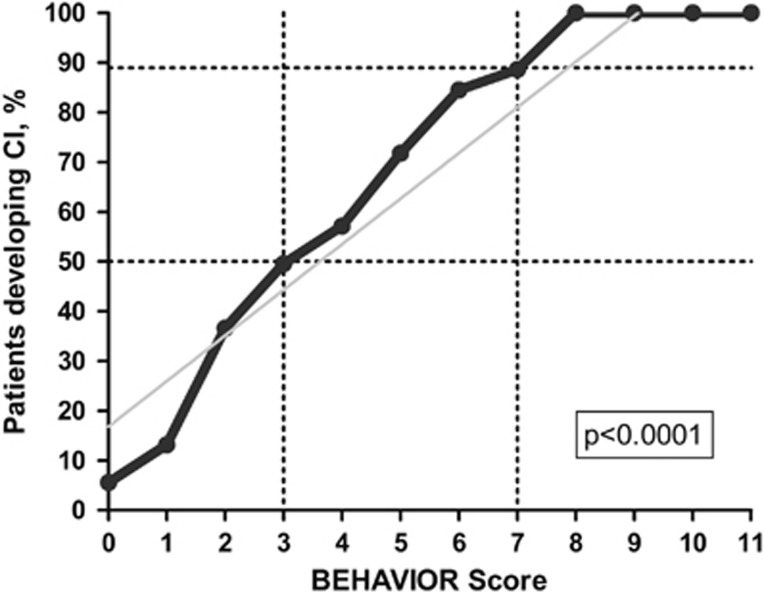

Predictive Value of the BEHAVIOR Score

There was a strong and direct association between the BEHAVIOR score and the CI rates (P<0.0001, Figure 1). Patients with a BEHAVIOR score of 3 had a nearly 50% probability to develop CI after SAH. The CI probability was over 90% in patients scoring 8 points or more (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Correlation between BEHAVIOR score and the portion of patients developing cerebral infarction (CI) on computed tomography (CT) scans within 6 weeks after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

Table 3. Correlation between BEHAVIOR score and incidence of CI.

| Score value | Patients developing CI (%) | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.6 | 1.5–18.1 |

| 1 | 13.2 | 7.7–21.7 |

| 2 | 36.6 | 28.6–45.4 |

| 3 | 49.6 | 40.8–58.4 |

| 4 | 57.1 | 46.0–67.6 |

| 5 | 71.8 | 56.2–83.5 |

| 6 | 84.5 | 74.4–91.1 |

| 7 | 88.6 | 76.0–95.1 |

| 8 | 100.0 | 70.1–100.0 |

| 9 | 100.0 | 80.6–100.0 |

| 10 | 100.0 | 51.0–100.0 |

| 11 | 100.0 | 20.7–100.0 |

Abbreviation: CI, cerebral infarction.

The internal validation of the BEHAVIOR score with a ROC curve (Figure 2) showed: (1) a wide area under the curve (0.806) indicating diagnostic accuracy of this score for the estimation of CI probability; (2) the superiority of the BEHAVIOR score to Hunt & Hess (area under the curve=0.747) and Fisher grades (area under the curve=0.666). The results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (P=0.345) indicated no evidence for poor calibration. The bootstrapping method confirmed the robustness of the score against possible variability.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for BEHAVIOR, Hunt & Hess, and Fisher scores.

According to cutoffs of CI probability, the BEHAVIOR score was additionally divided into three levels (Figure 3): low (0 to 2 points, average risk 23.6%), medium (3 to 6 points, average risk 62.3%) and high risk (7 to 11 points, average risk 93.2%) of CI development. The correlations between these groups showed the following OR values: OR=5.36 (95% confidence interval: 3.69 to 7.77) for medium versus low risk (P<0.0001) and OR=8.34 (95% confidence interval: 3.27 to 21.27) for high versus medium risk (P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Cerebral infarction (CI) rates with reference to low, medium, and high BEHAVIOR score.

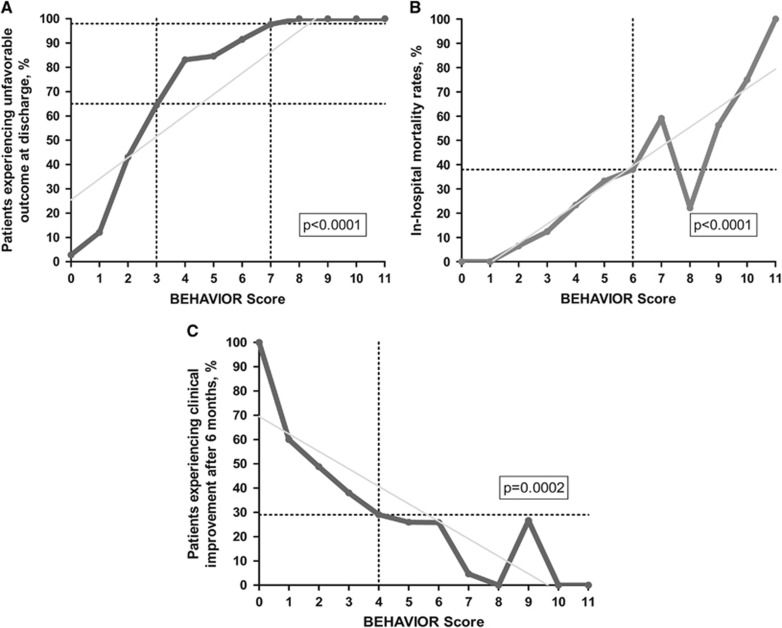

The BEHAVIOR score also significantly correlated with clinical outcome at discharge (Figure 4A), in-hospital mortality (Figure 4B), and clinical improvement at 6 months after SAH (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Correlation between expected outcome (BEHAVIOR score at admission) and observed outcome: (A) unfavorable outcome at discharge; (B) in-hospital mortality; (C) clinical improvement at 6 months after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The crossing of the dashed lines points to the most relevant score cutoffs for each correlation.

Discussion

Based on clinical and radiologic data from a large cohort of SAH patients, we derived a new risk score for early prediction of CI risk and for the prediction of clinical outcome.

Predictors of Cerebral Infarction after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Many potential predictors of CI—both present at admission and occurring during the course of SAH—have been previously reported.1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Aiming at the development of a clinically meaningful risk score allowing the estimation of CI risk already at the initial stage of SAH, we focused on predictors that are already available early after onset of SAH.

Scientific evidence in the literature on the predictive value of admission variables which were identified as independent predictors of CI in our study is very inconsistent. In contrast to the ‘typical' cerebral vasospasm that usually begins at the end of the first week after bleeding,3, 12 little is known about the predictive value of early vasospasm on admission angiography.1, 24, 25 As our data support the role of early vasospasm as a predictor of CI, we recommend paying particular attention to patients, especially when unconscious, who show angiographic vasospasm on admission DSA.

Elevated ICP is an important consequence of SAH that often results in decreased cerebral perfusion and secondary clinical decline.26 In our study, patients with sustained elevation of ICP >20 mm Hg despite initial placement of an EVD had significantly higher rates of CI. The crucial role of pathologic ICP in CI development should encourage a more aggressive ICP-managing strategy.

The association of higher age with CI has been reported previously and has been attributed to increased friability of brain tissue, larger SAH volumes resulting from brain atrophy, and a lower ischemic threshold of the elderly brain.3, 27 Congruent with our findings most authors also acknowledge an independent association between a higher admission grade and CI.3

The factors acute hydrocephalus,3, 9, 12, 13, 27 treatment of multiple aneurysms,28, 29 and the amount of subarachnoid blood on the initial CT scan3, 7, 12, 30 were significant in the multivariate analyses. Their predictive value for CI is being more controversially disputed in other studies compared with the above-mentioned independent predictors.

Cerebral Infarction Risk Score

To date, there are various risk scores targeted to SAH patients to assess the probability of cerebral vasospasm,31, 32 unfavorable outcome,33, 34 and occurrence of CI.35, 36 The most established scores include various radiographic parameters for risk estimation of symptomatic vasospasm beginning with the original Fisher score.19 The predictive power of later radiologic scores seems to be better.31, 32, 36 As to other scores, Lee et al33 recently published the HAIR score for risk stratification of in-hospital mortality after SAH based on Hunt&Hess score, age, the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage, and rebleeding. There is also the Acute Physiologic Derangements Score that was successfully evaluated for the prediction of unfavorable outcome34 and early CI.35

The score proposed here presents the first attempt to design a prediction model for CI occurrence after SAH using a combination of demographic, radiographic, and clinical variables on admission, allowing a very early identification of patients at risk for CI. Such a score might prompt a more intensive monitoring of patients or even an earlier start of specific preventive treatment strategies.37

Development and internal validation of the risk score was performed with established statistical methods, which have been used by other groups.22, 34 The BEHAVIOR score showed high predictive accuracy both for the radiographic (CI) and for the clinical outcome. In the present cohort, the BEHAVIOR score correlated better with clinical outcome than original Hunt&Hess and Fisher scores alone. The superiority of BEHAVIOR can be explained by the inclusion of a larger number of risk factors contributing to CI development. By this, the BEHAVIOR score reflects the currently favored theory of the multifactorial nature of CI.4, 38 Besides, all risk factors included in BEHAVIOR are collected and categorized easily compared with other scores.34 Therefore, it may be a reliable tool for clinicians allowing the early identification of high-risk patients right at the onset of the disease.

Limitations of the Study

After development of the BEHAVIOR score, we used multiple techniques of internal validation. This improves the likelihood of the score to be also useful in another SAH cohorts. Nevertheless, the BEHAVIOR score will need to undergo external validation in other SAH populations to be accepted.

Another limitation is the retrospective nature of this study. All correlated variables were collected from a SAH database, which was generated from an electronic medical history database. This strategy cannot provide the same accuracy as a prospectively enrolled cohort.

Finally, the limitations concerning the documentation of CI must be mentioned. Besides routine CT imaging on admission and postoperatively, all follow-up CT scans were performed only when clinically indicated. This might have led to a detection bias in favor of patients with worse clinical condition, as well as underestimation of asymptomatic infarctions.39 However we consider that such infarct monitoring was sufficient for the current study goal, as all included patients had at least one follow-up CT scan. Furthermore, we included CT scans up to 6 weeks after SAH to cover the crucial time for CI occurrence.5, 6, 7, 40

Conclusions

The BEHAVIOR score is a new tool for reliable identification of patients at risk for CI early after aneurysmal SAH. This infarct risk score passed internal validation successfully and also allows prediction of clinical outcome after SAH. Further external validation in other SAH cohorts is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give special thanks to Dr Beate Hippchen (Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Freiburg) for her assistance in data collection.

Author Contributions

Along with the first author (RJ), MR and VV has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; RR, MS, WN, and AW has been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; KK has participated in designing and performing of the statistical analyses; CT has assisted in the evaluation of radiographic data of patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism website (http://www.nature.com/jcbfm)

Supplementary Material

References

- 1Schmidt JM, Rincon F, Fernandez A, Resor C, Kowalski RG, Claassen J et al. Cerebral infarction associated with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2007; 7: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Juvela S, Kuhmonen J, Siironen J. C-reactive protein as predictor for poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012; 154: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Fergusen S, Macdonald RL. Predictors of cerebral infarction in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2007; 60: 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Rowland MJ, Hadjipavlou G, Kelly M, Westbrook J, Pattinson KT. Delayed cerebral ischaemia after subarachnoid haemorrhage: looking beyond vasospasm. Br J Anaesthesia 2012; 109: 315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Schmidt JM, Wartenberg KE, Fernandez A, Claassen J, Rincon F, Ostapkovich ND et al. Frequency and clinical impact of asymptomatic cerebral infarction due to vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2008; 109: 1052–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Juvela S, Siironen J, Varis J, Poussa K, Porras M. Risk factors for ischemic lesions following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Rabinstein AA, Friedman JA, Weigand SD, McClelland RL, Fulgham JR, Manno EM et al. Predictors of cerebral infarction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2004; 35: 1862–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Kivisaari RP, Salonen O, Servo A, Autti T, Hernesniemi J, Ohman J. MR imaging after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and surgery: a long-term follow-up study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 1143–1148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Rabinstein AA, Weigand S, Atkinson JL, Wijdicks EF. Patterns of cerebral infarction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2005; 36: 992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Siironen J, Porras M, Varis J, Poussa K, Hernesniemi J, Juvela S. Early ischemic lesion on computed tomography: predictor of poor outcome among survivors of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2007; 107: 1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Hwang G, Jung C, Sheen SH, Kim SH, Park SQ, Oh CW et al. Procedural predictors of delayed cerebral infarction after intra-arterial vasodilator infusion for vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010; 152: 1503–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Crowley RW, Medel R, Dumont AS, Ilodigwe D, Kassell NF, Mayer SA et al. Angiographic vasospasm is strongly correlated with cerebral infarction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2011; 42: 919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Brown RJ, Kumar A, Dhar R, Sampson TR, Diringer MN. The relationship between delayed infarcts and angiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2013; 72: 702–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Jabbarli R, Glasker S, Weber J, Taschner C, Olschewski M, Van Velthoven V. Predictors of severity of cerebral vasospasm caused by aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 22: 1332–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Jabbarli R, Shah M, Taschner C, Kaier K, Hippchen B, Van Velthoven V. Clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of CT-angiography in the diagnosis of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Jabbarli R, Reinhard M, Niesen WD, Roelz R, Shah M, Kaier K et al. Predictors and impact of early cerebral infarction after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur J Neurol 2015. doi:10.1111/ene.12686 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1968; 28: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Fisher CM, Kistler JP, Davis JM. Relation of cerebral vasospasm to subarachnoid hemorrhage visualized by computerized tomographic scanning. Neurosurgery 1980; 6: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Graeb DA, Robertson WD, Lapointe JS, Nugent RA, Harrison PB. Computed tomographic diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage. Etiology and prognosis. Radiology 1982; 143: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, Barsan WG, Sauerbeck LR, Zuccarello M et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke 1996; 27: 1304–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Bender JM, Ampofo K, Gesteland P, Stoddard GJ, Nelson D, Byington CL et al. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting hospitalization in children with influenza virus infection. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 25: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, Altman DG et al. Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart 2012; 98: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Baldwin ME, Macdonald RL, Huo D, Novakovic RL, Goldenberg FD, Frank JI et al. Early vasospasm on admission angiography in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is a predictor for in-hospital complications and poor outcome. Stroke 2004; 35: 2506–2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Qureshi AI, Sung GY, Suri MA, Straw RN, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Prognostic value and determinants of ultraearly angiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 1999; 44: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Mack WJ, King RG, Ducruet AF, Kreiter K, Mocco J, Maghoub A et al. Intracranial pressure following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: monitoring practices and outcome data. Neurosurg Focus 2003; 14: e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Shimoda M, Takeuchi M, Tominaga J, Oda S, Kumasaka A, Tsugane R. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic infarcts from vasospasm in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: serial magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery 2001; 49: 1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Jeon P, Kim BM, Kim DJ, Kim DI, Suh SH. Treatment of multiple intracranial aneurysms with 1-stage coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1170–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Wachter D, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Gilsbach JM, Rohde V. Early surgery of multiple versus single aneurysms after subarachnoid hemorrhage: an increased risk for cerebral vasospasm? J Neurosurg 2011; 114: 935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Juvela S, Siironen J. Early cerebral infarction as a risk factor for poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Frontera JA, Claassen J, Schmidt JM, Wartenberg KE, Temes R, Connolly ES, Jr. et al. Prediction of symptomatic vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the modified fisher scale. Neurosurgery 2006; 59: 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Dupont SA, Wijdicks EF, Manno EM, Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA. Prediction of angiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: value of the Hijdra sum scoring system. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11: 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Lee VH, Ouyang B, John S, Conners JJ, Garg R, Bleck TP et al. Risk stratification for the in-hospital mortality in subarachnoid hemorrhage: the HAIR score. Neurocrit Care 2014; 21: 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Claassen J, Vu A, Kreiter KT, Kowalski RG, Du EY, Ostapkovich N et al. Effect of acute physiologic derangements on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Naidech AM, Drescher J, Tamul P, Shaibani A, Batjer HH, Alberts MJ. Acute physiological derangement is associated with early radiographic cerebral infarction after subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 1340–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Kramer AH, Hehir M, Nathan B, Gress D, Dumont AS, Kassell NF et al. A comparison of 3 radiographic scales for the prediction of delayed ischemia and prognosis following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2008; 109: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Laskowitz DT, Kolls BJ. Neuroprotection in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2010; 41: S79–S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Vergouwen MD, Etminan N, Ilodigwe D, Macdonald RL. Lower incidence of cerebral infarction correlates with improved functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Rosenberg NF, Liebling SM, Kosteva AR, Maas MB, Prabhakaran S, Naidech AM. Infarct volume predicts delayed recovery in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and severe neurological deficits. Neurocrit Care 2013; 19: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Naidech AM, Bendok BR, Bassin SL, Bernstein RA, Batjer HH, Bleck TP. Classification of cerebral infarction after subarachnoid hemorrhage impacts outcome. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: 1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.