Abstract

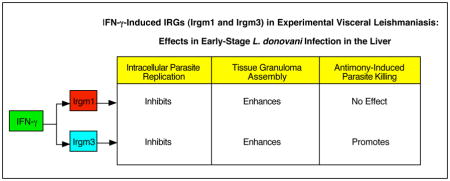

In C57BL/6 mice, Leishmania donovani infection in the liver provoked IFN-γ induced expression of the immunity-related GTPases (IRG), Irgm1 and Irgm3. To gauge the antileishmanial effects of these macrophage factors in the liver, intracellular infection was analyzed in IRG-deficient mice. In early- (but not late-) stage infection, Irgm3−/− mice failed to properly control parasite replication, generated little tissue inflammation and were hyporesponsive to pentavalent antimony (Sb) chemotherapy. Observations limited to early-stage infection in Irgm1−/− mice demonstrated increased susceptibility and virtually no inflammatory cell recruitment to heavily-parasitized parenchymal foci but an intact response to chemotherapy. In L. donovani infection in the liver, the absence of either Irgm1 or Irgm3 impairs early inflammation and initial resistance; the absence of Irgm3, but not Irgm1, also appears to impair the intracellular efficacy of Sb chemotherapy.

Keywords: visceral leishmaniasis, Leishmania donovani, Irgm1, Irgm3

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Leishmania donovani, an agent of visceral leishmaniasis, targets and replicates within resident macrophages in the liver, spleen and bone marrow. In wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 (B6) mice, experimental infection in the liver progresses until either chemotherapy is given or a T cell-dependent response develops to induce macrophage activation (1–6). Net expressions of this cytokine-driven inflammatory response, in which IFN-γ plays a prominent activating role (7), include granuloma assembly encircling parasitized macrophages, intracellular parasite killing and a subsequent near-cure phenotype in the liver (1–9).

To kill L. donovani, IFN-γ induces and the activated macrophage utilizes both phagocyte oxidase (phox) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (10,11). Results in livers of B6 mice deficient in phox, iNOS or both (double knockouts (DKO)) indicate that the macrophage makes early but transient use of its phox-induced respiratory burst mechanism. In contrast, iNOS is required in all phases of defense against L. donovani infection (early control, parasite killing, near-resolution); in its absence, replication is unrestrained and liver infection reaches high levels (10,11).

Nevertheless, observations made in studying the host’s role in the response to antileishmanial chemotherapy also point to IFN-γ-regulated macrophage mechanisms unrelated to iNOS or phox (1,11). In the L. donovani-infected liver, an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism is required for expression of the intracellular leishmanicidal effect of conventional chemotherapy, pentavalent antimony (SbV) (7). In mice deficient in both iNOS and phox, initial Sb-induced killing is diminished (by ~ 50%) (11) but not absent as in IFN-γ−/− mice (7), indicating the activity of other IFN-γ-induced macrophage mechanisms. In addition, despite an initially impaired response to Sb and the requirement for iNOS to control infection (10,11), Sb-treated iNOS/phox DKO mice subsequently eliminated ~ 90% of liver amastigotes and residual infection did not relapse (11). Since IFN-γ is also required to keep surviving intracellular parasites in a quiescent state to maintain the durable response to chemotherapy (1), this observation in DKO mice also supports the idea that IFN-γ can regulate an intracellular antileishmanial mechanism distinct from iNOS and phox.

One such candidate for this IFN-γ-regulated, iNOS/phox-independent macrophage antimicrobial mechanism is the immunity-related p47 GTPase (IRG) family (12–15). Finding that L. donovani infection induced IRG expression in the liver prompted us to test the actions of two representative IRGs -- Irgm1 (LRG-47) and Irgm3 (IGTP), members of the IRG GMS subfamily (13).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and liver infection

C57BL/6J (B6) WT mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Breeding pairs of the following mice (B6 background) were obtained and bred at Weill Cornell Medical College: IFN-γ−/− (Jackson Laboratories) and Irgm1−/− and Irgm3−/− (VA Medical Center, Durham, NC) (16,17). Irgm1−/− and Irgm3−/− mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6NCr1 mice for 9 and 10 generations, respectively. Mice were female and 6–12 weeks old at the time of infection. However, female Irgm1−/− mice are sterile and breeding to yield homozygous-deficient animals was slow, largely unproductive and was terminated. Thus, in the experiments shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, Irgm1−/− mice were 10–24 weeks old when infected, while the WT controls tested in parallel were 6–12 weeks old.

Table 1.

Response to Pentavalent Antimony (Sb) Chemotherapy.*

| Mice | Sb | Liver Parasite Burden (LDU) | % Killing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 | Day 21 | |||

| A. WT | 0 | 1991 ± 122 (16) | 2089 ± 167 (15) | 0 |

| + | 105 ± 17 (16) | 95 ± 1 | ||

| Irgm3−/− | 0 | 2879 ± 139 (18) | 2951 ± 201 (17) | 0 |

| + | 1380 ± 94 (17) | 52 ± 1+ | ||

| B. WT | 0 | 2551 ± 101 (7) | 2640 ± 128 (7) | 0 |

| + | 57 ± 22 (7) | 98 ± 5 | ||

| Irgm1−/− | 0 | 3875 ± 147 (6) | ND** | |

| + | 370 ± 64 (5) | 91 ± 3 | ||

2 weeks after infection (day +14), mice received no treatment or a single IP injection of Sb (500 mg/kg). Day +21 LDU were compared to day +14 LDU to determine parasite killing (% reduction in LDU on day +21). Results (mean ± SEM values) are from 4 experiments in (A) and 2 in (B) with (n) mice per time point.

p <.05 vs. Sb-treated WT mice.

ND (not done – insufficient Irgm1−/− mice to test (see text)).

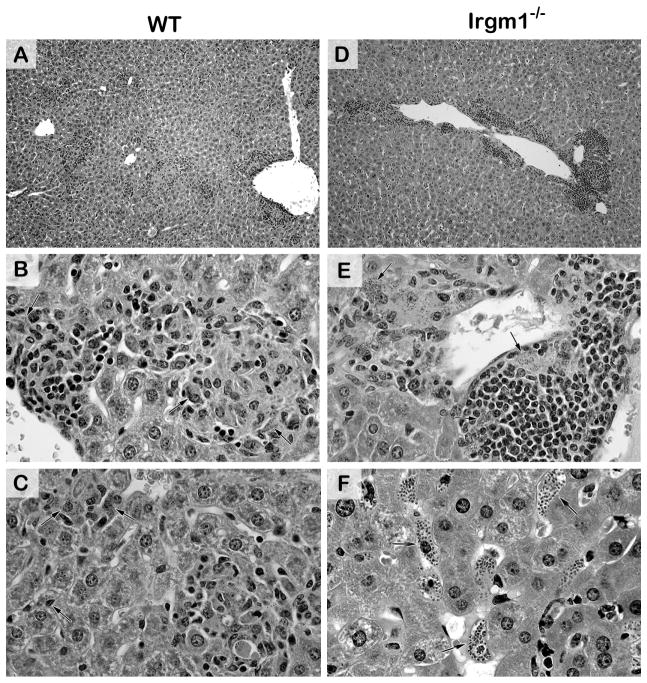

Figure 5.

Histologic response to L. donovani in livers of WT (A–C) and Irgm1−/− mice (D–F) in early-stage infection at week 2. WT mice show developing and mature perivascular granulomas (A, B) and developing granulomas distributed throughout the parenchyma at infected foci (A, C). Arrows indicate parasitized Kupffer cells that have (B) or have not yet (C) attracted a mononuclear cell inflammatory response. Irgm1−/− mice (D–F) show exaggerated perivascular accumulation of inflammatory cells and some adjacent granuloma assembly at heavily-infected foci (arrows) (D, E), but little or no mononuclear cell recruitment at virtually all parenchymal foci (D), comprised of remarkably parasitized Kupffer cells (arrows) (F). In (F), perivascular inflammation is shown at the lower right. Original magnification, x100 (A,D) and x400 (B, C, E and F).

Groups of 3–5 mice were injected via the tail vein with 1.5 × 107 hamster spleen homogenate-derived L. donovani amastigotes (LV9 strain). Infection was assessed microscopically using Giemsa-stained liver imprints in which parasite burdens were measured by blinded counting of the number of amastigotes per 500 cell nuclei x organ weight (mg) (Leishman-Donovan units (LDU)) (3). Differences between mean values were analyzed by a two-tailed Student’s t test. These studies were approved by the Medical College’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and animals were housed and managed in the Medical College’s animal facility (RARC).

2.2. Gene and mRNA expression in liver tissue

A high-density oligonucleotide microarray system, Murine Genome U74A Array version 2 containing 12,488 genes (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), was used to test liver tissue from uninfected and infected WT and IFN-γ−/− mice. Total RNA was isolated from freshly obtained tissue, and samples from 4–5 mice from each group were pooled. Performance of the microarray experiment and the associated data analyses were carried out as previously described (18).

For quantitative real-time RT-PCR testing, total RNA was isolated from liver tissue from individual mice using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. RT-PCR was performed in an ABI 7400 System using the SYBR GREEN PCR kit. GAPDH mRNA expression was used as the control for quantitative analysis. The primers for detected genes are listed in Table S1. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial incubation step of 2 min at 50°C, reverse transcription of 60 min at 60°C and 94°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C for denaturation and 2 min at 62°C for annealing and extension. To calculate relative RNA levels, we used the formula: 2^(−ΔCt) where ΔCt = Ct (specific gene) – Ct (GAPDH) (18).

2.3. Tissue granuloma responses

The histologic response to infection was evaluated microscopically in liver sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The number of granulomas (infected Kupffer cells which had attracted ≥ 5 mononuclear cells (3)) was counted in 100 consecutive 40x fields and, at 100 parasitized foci, the granulomatous reaction was scored as none, developing, mature and/or parasite-free (3,7). Mature granulomas show a core of fused parasitized Kupffer cells, numerous surrounding mononuclear cells and epitheloid-type changes (8).

2.4. Treatments

Groups of 3–5 mice were injected once IP two weeks after infection (day +14) with 0.2 ml of saline containing pentavalent antimony (SbV) (sodium stibogluconate, Pentostam, Wellcome Foundation Ltd., London, UK) using an optimal leishmanicidal dose (500 mg/kg) (3). Optimal-dose amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) (X-Gen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Big Flats, NY) was injected IP on days +14, +16 and +18 (1). Liver parasite burdens in all treated mice were determined on day +21, and parasite killing was calculated as indicated in the Table 1 legend (3). Some Sb-injected Irgm3−/− mice were left undisturbed for 10 additional weeks to test for posttreatment relapse at week 12 (1).

2.5. IFN-γ protein determination

IFN-γ activity was measured in serum and spleen cell culture supernatants using an ELISA kit (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) (3). Spleen cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were stimulated for 48h with 30 ug/ml of soluble L. donovani antigen, generously provided by Dr. Abhay Satoskar (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) (19).

3. Results and Discussion

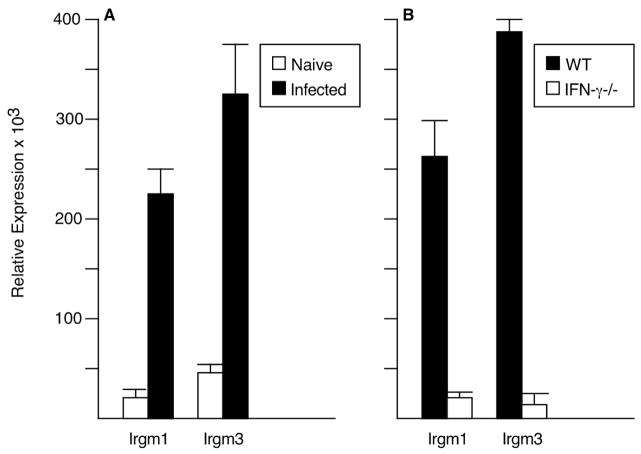

3.1. Expression of Irgm1 and Irgm3 is induced by IFN-γ in L. donovani infection

Microarray gene expression analysis, performed using liver tissue from WT and IFN-γ−/− mice at week 2 and 3 after infection, demonstrated enhanced expression of five IRGs in WT mice -- Irgm1 and Irgm3 as well as Irgm2 (GTPI), Irgd and Irgb6 (TGTP/Mg21 (Table S2). In contrast, there was essentially no induction of IRG gene expression in infected IFN-γ−/− mice. The findings for Irgm1 and Irgm3 were confirmed by RT-PCR testing using 3-week infected livers (Figure 1), and showed the following fold-increases in mRNA expression vs. mean values in uninfected mice: Irgm1 (7.0), and Irgm3 (7.0) in WT mice (Figure 1A) and < 1 fold-increases in expression of these IRGs in IFN-γ−/− mice (Figure 1B). IRGs are thought to be expressed in most nucleated cells (along with other IFN-γ-induced genes) (20), and while these proteins may coordinate immune function in other cells in murine models (21,22), there is little doubt of their role in macrophages, the primary targets for Leishmania, In mouse models, IRGs regulate intracellular microbial killing, primarily linked to regulation of autophagic processing of pathogen-containing phagosomes, as well as macrophage motility and cytokine secretion (12–15,23,24).

Figure 1.

Relative mRNA expression of Irgm1 and Irgm3 three weeks after L. donovani challenge in livers of (A) uninfected (naïve) vs. infected WT mice, and (B) infected WT vs. infected IFN-γ−/− mice. RT-PCR results (mean ± SEM) are from 2 experiments in (A) (8 mice per group) and 1 experiment in (B) (4 mice per group). p <.05 for all results in (A) for infected vs. naive WT mice (A) and in (B) for infected WT vs. infected IFN-γ−/− mice.

3.2. Irgm3 regulates the initial response to Sb chemotherapy

Since the IFN-γ-regulated macrophage antileishmanial mechanism that acts independently of iNOS and phox was identified in the context chemotherapy (1,11), we first tested IRG-deficient mice for responsiveness to treatment. Two weeks after infection (day +14), mice were injected once with optimal-dose Sb which did not enhance IRG gene expression in WT mice (Table S2). Irgm1−/− mice appeared to respond normally to Sb since 91% of amastigotes had been eradicated by day +21 (Table 1). (The small number of available Irgm1−/− mice [see Methods], however, limited testing to 2 experiments in which we had to forego the day +21 time point in untreated mice except for one [which showed high level infection -- 6621 LDU]. Without complete data for day +21, it remains possible that liver parasite killing in treated Irgm1−/− mice reflected an effect other than an intact response to Sb. However, we believe this possibility is unlikely, especially in view of the extent of infection on day 14 (see Figure 5F). In contrast, Irgm3 was required for Sb’s full effect since drug-induced parasite killing was reduced by nearly one-half in Irgm3−/− vs. WT mice (52% vs. 95% killing).

Additional testing in three-week infected Irgm3−/− and WT mice demonstrated that (a) relative mRNA expression of IFN-γ, iNOS and phox (as judged by expression of gp91, gp67, p47 and p40 subunits) in liver tissue, (b) serum IFN-γ activity, and (c) IFN-γ secretion by antigen-stimulated spleen cells were similar (2 experiments for each assay, n = 7–8 mice per group, data not shown). These results, coupled with previous reports of intact IFN-γ and iNOS activities in Irgm3−/− mice (16,25,26), suggest an IFN-γ-induced, iNOS- and phox-independent, chemotherapy-enabling action for Irgm3. This optimizing action was specific for Sb in that Irgm3−/− mice responded fully to an alternative antileishmanial agent, amphotericin B (1), showing 98 ± 1% parasite killing on day +21 (2 experiments, n = 8 mice, data not shown). While Sb’s leishmanicidal efficacy requires T cells, IFN-γ and activated macrophage mechanisms (iNOS and phox act in concert to regulate ~ 50% of Sb’s intracellular killing effect), (7,11,27), amphotericin B’s initial antleishmanial efficacy requires none of these host factors (1).

3.3 Irgm3 is not required for posttreatment cure

Sb-hyporesponsive Irgm3−/− mice were also examined 10 weeks after drug injection for evidence of persistent infection. At week 12, long after Sb’s effect had waned, however, liver parasite burdens were barely measureable (17 ± 5 LDU) as was the case in treated WT mice (2 ± 1 LDU) (2 experiments, 6–7 mice per group). This result suggested that Irgm3’s role in the L. donovani-infected liver might be limited, prompting testing in untreated mice to gauge effects that Irgm3 may have in addition to promoting the initial response to Sb chemotherapy.

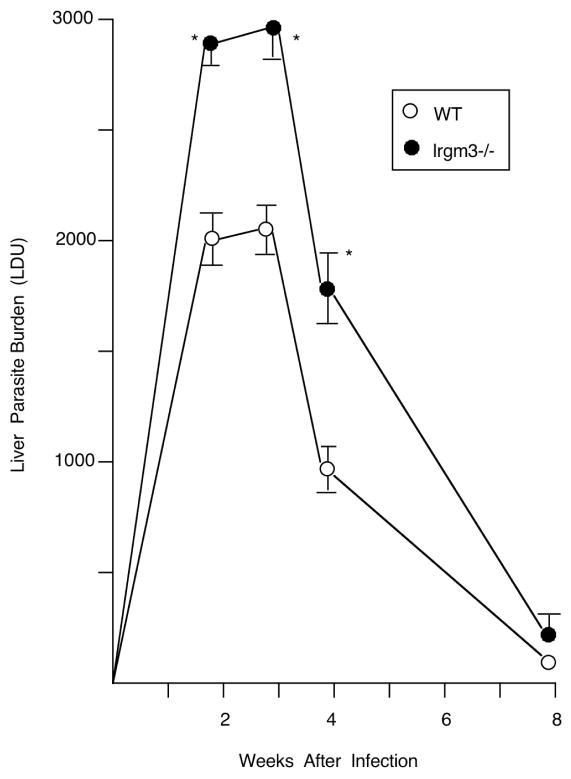

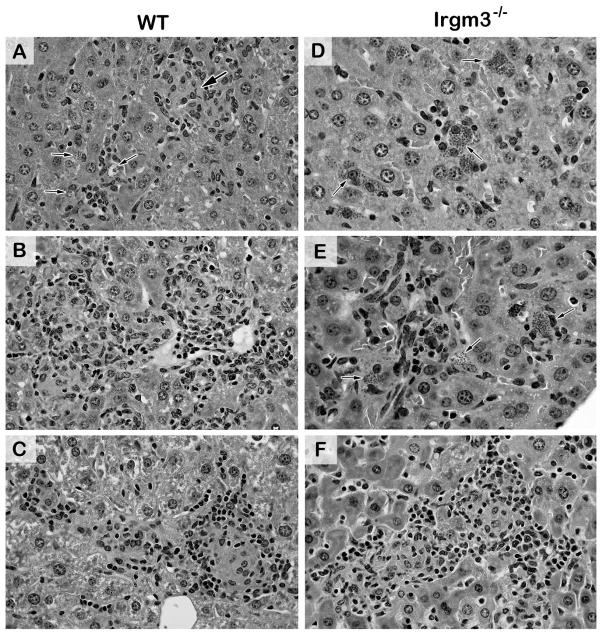

3.4 Kinetics of infection in the liver and tissue inflammatory response in untreated IRG-deficient animals

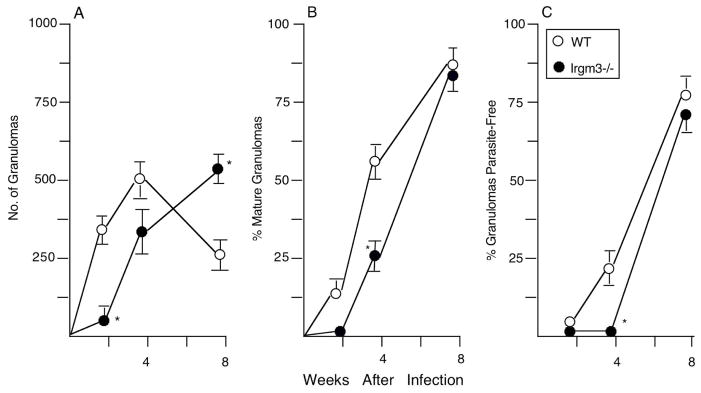

As shown in Figure 2, Irgm3−/− mice failed to properly control parasite replication during the initial stage of infection, indicating an early antileishmanial action. At week 2, increased liver burdens were accompanied by the failure to generate a mononuclear cell inflammatory response at most parasitized liver foci (Figures 3, 4 and S1). By week 4, however, parasite killing was underway in Irgm3−/− mice along with some developing tissue inflammation, and by week 8, mature granulomas were fully-established coinciding with expression of the self-cure phenotype.

Figure 2.

Course of L. donovani infection in livers of WT and Irgm3−/−. Results, from 3 experiments, indicate mean ± SEM values for 10–16 mice per group at each time point. *p <.05 vs. the corresponding WT liver parasite burden (LDU).

Figure 3.

Histologic reaction to L. donovani in livers of WT (A–C) and Irgm3-deficient mice (D–F) 2–8 weeks after infection. In WT mice, infected foci show inflammatory responses ranging from little or none (arrows) to developing granulomas (large arrow) at week 2 (A), mature and coalescing granulomas at week 4 (B), and residual mature and involuting granulomas at week 8 (C). In contrast, in Irgm3−/− mice, few of numerous heavily-infected Kupffer cells (arrows) have attracted mononuclear cells at week 2 (D), developing granulomas have emerged at some foci but all remain heavily-parasitized (arrows) at week 4 (E), but by week 8, the granulomatous response is fully-expressed and most granulomas are parasite-free (F). Original magnification, x400. See Figure S1 for corresponding low-power photomicrographs.

Figure 4.

Liver granuloma assembly (A), maturation (B) and antileishmanial function (C) after L. donovani challenge in WT and Irgm3−/− mice. Results are from 2 experiments, and show mean ± SEM values for 6–7 mice per group at each time point. *p <.05 vs. corresponding WT result.

In early-stage infection in Irgm1−/− mice, liver parasite burdens at week 2 were significantly increased vs. WT mice (Table 1, p <.05); histologic sections showed widespread infection along with exaggerated perivascular accumulations of mononuclear cells (Figure 5). However and pointing to a defect in additional cell recruitment or migration noted in other models (22,28), there was little inflammatory and no granulomatous reaction at more distant parasitized parenchymal foci. These parenchymal foci were mostly comprised of infected Kupffer cells alone, distended by large numbers of replicating amastigotes (Figure 5F).

Since breeding efforts were largely unproductive in Irgm1−/− mice, we first used homozygous-deficient mice to address the discrete question of Irgm1’s role in the response to chemotherapy (Table 1). We prioritized our remaining mice to determine if at week 8 liver parasite burdens were high or the self-cure phenotype was expressed. However, in this final experiment, five of six untreated Irgm1−/− (but no WT) mice died unexpectedly without necropsy during week 5 after infection. The liver burden in the single survivor at week 8 was high (4459 LDU), and we suspect that these animals died from overwhelming infection, as reported in Irgm1−/− mice challenged with other intracellular organisms (12,13). However, it is worth noting that despite similarly high liver parasite burdens (7,10), IFN-γ−/− and iNOS/phox DKO mice seldom die from L. donovani infection.

When viewed together, our results in early-stage liver infection in gene-deficient mice, suggest that both Irgm1 and Irgm3 restrain parasite replication and promote tissue inflammation. Irgm1−/− mice are recognized as pan-susceptible (sometimes markedly so) to infection caused by diverse intracellular pathogens (12,13). Irgm3−/− mice show a more narrow spectrum of susceptibility (e.g., to Toxoplasma gondii, Chlamydia sp. and L. major (unpublished)) (12,13) to which early-stage L. donovani infection can now be added (Figure 2). Whether Irgm1 and Irgm3 also regulate antileishmanial events in other L. donovani-infected organs, including spleen and bone marrow, remains to be clarified.

In addition, Irgm3, but apparently not Irgm1, also regulated the intracellular efficacy of Sb chemotherapy. The requirement for IFN-γ in the expression of Sb’s in vivo leishmanicidal effect (7) may well be explained, then, by its capacity to induce multiple mechanisms in the activated macrophage – iNOS and phox which act in concert (11) and Irgm3 which presumably acts separately. If this idea is correct and if triple-deficient mice, deficient in iNOS, phox and Irgm3, were available and tested, one would predict no leishmanicidal response to Sb treatment similar to IFN-γ−/− mice (7). However, it is possible that iNOS/phox and Irgm3 are not independent factors, but are linked in facilitating the intracellular killing action of Sb. For example, members of a related family of GTPases, the guanylate binding proteins, have been reported to assemble and activate phox to promote macrophage oxidative antimicrobial activity (14,29). Such an effect, however, has not been described for an IRG nor for iNOS. Another idea worth also considering in future studies is that within the cytoplasm of the IFN-γ-activated macrophage, Irgm3 along with iNOS/phox promotes the optimal environment for drug metabolism – in the case of pentavalent Sb, conversion of SbV, thought to be a pro-drug, to SbIII, its active leishmanicidal trivalent form (30,31).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Low-power photomicrographs of livers of WT (A–C) and Irgm3−/− mice. (D–F) 2–8 weeks after L. donovani infection. In comparison to WT mice, the tissue inflammatory reaction in Irgm3−/− mice is minimal at week 2 (D), but developing at week 4 (E) and fully-established with granulomas at week 8 (F). Original magnification, x100.

Table S1. Primer Sequences Used for RT-PCR.

Table S2. Gene Expression in L. donovani-Infected Livers.*

Highlights.

IFN-γ induces expression of immunity-related GTPases (IRG) in Leishmania donovani infection in the liver

In liver, both Irgm1 and Irgm3 promote early intracellular resistance and granuloma assembly

Irgm3, but not Irgm1, optimizes macrophage parasite killing induced by antimony chemotherapy

IFN-γ-induced IRGs exert regulatory antileishmanial effects

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants 5R01AI083219 (HWM, XM) and R01AI57831 (GAT) and a VA Merit Review grant (GAT). We also thank Yunhua Zhang for her technical assistance and Dr. Yan Zhang for assistance with the PCR analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Murray HW. Prevention of relapse after chemotherapy in a chronic intracellular infection: mechanisms in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2005;174:4916–4923. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray HW. Progress in treatment of a neglected disease: visceral leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2004;2:279–292. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray HW, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Raman VS, Reed SG, Ma X. Regulatory actions of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 in Leishmania donovani infection in the liver. Infect Immun. 2013;81:2318–2326. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01468-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaye PM, Svensson M, Ato M, Maroof A, Polley R, Stager S, Zubairi S, Engwerda CR. The immunopathology of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:239–253. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley AC, Engwerda CR. Balancing immunity and pathology in visceral leishmaniasis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:138–147. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb7100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R, Nylen S. Immunobiology of visceral leishmaniasis. Frontiers Immunol. 2012;3:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray HW, Delph-Etienne S. Role of endogenous gamma interferon and macrophage microbicidal mechanisms in host response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:288–293. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.288-293.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray HW. Tissue granuloma structure-function in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2001;82:249–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2001.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beattie L, Peltan A, Maroof A, Kirby A, Brown N, Coles M, Smith DF, Kaye PM. Dynamic imaging of experimental Leishmania donovani-induced hepatic granulomas detects Kupffer cell-restricted antigen presentation to antigen-specific CD8 T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(3):e1000805. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray HW, Nathan CF. Macrophage microbicidal mechanisms in vivo: reactive nitrogen vs. intermediates in the killing of intracellular visceral Leishmania donovani. J Exp Med. 1999;189:741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray HW, Xiang Z, Ma X. Responses to Leishmania donovani in mice deficient in both phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1013–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor GA, Feng CG, Sher A. p47 GTPases: regulators of immunity to intracellular pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:100–109. doi: 10.1038/nri1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunn JP, Feng CG, Sher A, Howard JC. The immunity-related GTPases in mammals: a fast-evolving cell-autonomous resistance system against intracellular pathogens. Mamm Genome. 2011;22:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9293-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacMicking JD. Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:367–382. doi: 10.1038/nri3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim B-H, Shenoy AR, Kumar P, Bradfeild CJ, MacMicking JD. IFN-inducible GTPases in host cell defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor GA, Collazo CM, Yap GS, Nguyen K, Gregorio TA, Taylor LS, Eagleson B, Secrest L, Southon EA, Reid SW, Tessarollo L, Bray M, McVicar DW, Komschlies KL, Young HA, Biron CA, Sher A, Vande Woude GF. Pathogen-specific loss of host resistance in mice lacking the IFN-γ-inducible gene IGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:751–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collazo CM, Yap GS, Sempowski GD, Lusby KC, Tessarollo L, Woude GF, Sher A, Taylor GA. Inactivation of LRG-47 and IRG-47 reveals a family of interferon-γ-inducible genes with essential, pathogen-specific roles in resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 2001;194:181–188. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi X, Liu L, Xiang Z, Mitsuhashi M, Wu R, Ma X. Gene expression analysis in interleukin-12-induced suppression of mouse mammary carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:570–578. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khadem F, Mou Z, Liu D, Varikuti S, Satoskar A, Uzonna JE. Deficiency of p110 isoform of the phosphoinositide 3 kinase leads to enhanced resistance to Leishmania donovani. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6):e2951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrar MA, Schreiber RD. The molecular cell biology of interferon-gamma and its receptor. Ann Rev Immunol. 1993;11:571–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halonen SK, Taylor GA, Weiss LM. Interferon-gamma induced inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii in astrocytes is mediated by IGTP. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5573–5578. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5573-5576.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng CG, Collazo-Custodio CM, Eckhaus M, Hieny S, Belkaid Y, Elkins K, Jankovic D, Taylor GA, Sher A. Mice deficient in LRG-47 display increased susceptibility to mycobacterial infection associated with the induction of lymphopenia. J Immunol. 2004;172:1163–1168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henry SC, Traver M, Daniell X, Indaram M, Oliver T, Taylor GA. Regulation of macrophage motility by Irgm1. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:333–343. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bafica A, Feng CG, Santiago HC, Aliberti J, Cheever A, Thomas KE, Taylor GA, Vogel SN, Sher A. The IFN-inducible GTPase LRG-47 (Irgm1) negatively regulates TLR4-triggered proinflammatory cytokine production and prevents endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2007;179:5514–5522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacMicking JD, Taylor GA, McKinney JD. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-γ-inducible LRG-47. Science. 2003;302:654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1088063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butcher BA, Greene RI, Henry SC, Annecharico, Weinberg JB, Dnekers EY, Sher A, Taylor GA. P47 GTPases regulate Toxoplasma gondii survival in activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3278–3286. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3278-3286.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray HW, Oca MJ, Schreiber RD. Requirement for T cells and effect of lymphokines in successful chemotherapy for an intracellular infection. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1253–1257. doi: 10.1172/JCI114009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry SC, Daniell, Indaram M, Whitesides JF, Sempowski GD, Howell D, Oliver T, Taylor GA. Impaired macrophage function underscores susceptibility to Salmonella in mice lacking Irgm1 (LRG-47) J Immunol. 2007;179:6963–6972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim B-H, Shenoy AR, Kumar P, Das R, Tiwari S, MacMicking JD. A family of IFN-γ-inducible 65-kD GTPases protects against bacterial infection. Science. 2011;332:717–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frezard F, Demicheli C, Ribeiro RR. Pentavalent antimonials: new prespectives for old drugs. Molecules. 2009;14:2317–2336. doi: 10.3390/molecules14072317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts WL, Berman JD, Rainey PM. In vitro antileishmanial properties of tri- and pentavalent antimonial preparations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1234–1239. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Low-power photomicrographs of livers of WT (A–C) and Irgm3−/− mice. (D–F) 2–8 weeks after L. donovani infection. In comparison to WT mice, the tissue inflammatory reaction in Irgm3−/− mice is minimal at week 2 (D), but developing at week 4 (E) and fully-established with granulomas at week 8 (F). Original magnification, x100.

Table S1. Primer Sequences Used for RT-PCR.

Table S2. Gene Expression in L. donovani-Infected Livers.*