A novel experiment supports quantum computation using photonic circuits to greatly increase quantum device speed.

Keywords: Boson Sampling, Integrated quantum photonics, Quantum information processing, Quantum walk, Quantum simulations, Quantum optics, Quantum supremacy, Multiphoton quantum interference, Bosonic coalescence

Abstract

Boson sampling is a computational task strongly believed to be hard for classical computers, but efficiently solvable by orchestrated bosonic interference in a specialized quantum computer. Current experimental schemes, however, are still insufficient for a convincing demonstration of the advantage of quantum over classical computation. A new variation of this task, scattershot boson sampling, leads to an exponential increase in speed of the quantum device, using a larger number of photon sources based on parametric down-conversion. This is achieved by having multiple heralded single photons being sent, shot by shot, into different random input ports of the interferometer. We report the first scattershot boson sampling experiments, where six different photon-pair sources are coupled to integrated photonic circuits. We use recently proposed statistical tools to analyze our experimental data, providing strong evidence that our photonic quantum simulator works as expected. This approach represents an important leap toward a convincing experimental demonstration of the quantum computational supremacy.

INTRODUCTION

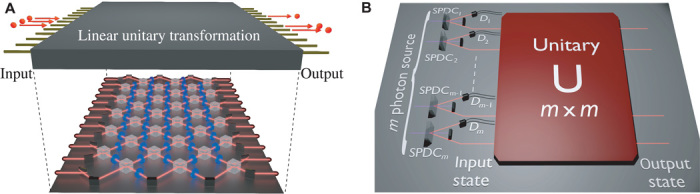

Theory has shown that quantum computers should be able to markedly outperform conventional, classical computers in specific tasks (1). In practice, however, no quantum computer has yet solved a problem instance which is hard to solve classically. With the goal of rigorously establishing what was called quantum supremacy, in 2010 Aaronson and Arkhipov provided strong theoretical evidence that a simpler, specialized quantum computer could solve a classically hard computational task (2). The so-called boson sampling problem consists of sampling from the output distribution of n indistinguishable photons entering different input modes of a given m-mode random interferometer (see Fig. 1A). The complex multiphoton interference within the device was shown, under mild computational assumptions, to yield an output distribution that is hard to sample using classical computers. The difficulty has been traced back to the known intractability of calculating the permanent function of a matrix (3). Indeed, each output’s probability amplitude is given by the permanent of a different n × n matrix obtained from the m × m unitary matrix U describing the interferometer (2, 4, 5).

Fig. 1. Boson sampling and its scattershot configuration.

(A) Conceptual scheme of boson sampling with n bosons undergoing an arbitrary m-mode unitary transformation. The problem is to sample from the output distribution of the n-bosons over the m-modes. This task can be efficiently performed by a specialized quantum computer performing n-photon interference in an m-mode linear interferometer implementing the chosen unitary transformation. (B) Scattershot configuration for boson sampling with randomly chosen inputs. m heralded single-photon sources, one for each input port, are coupled to the interferometer. During a given time period, n photons (n < m) are probabilistically injected into the interferometer. Each detected n-photon event at the interferometer’s output can be assigned to its corresponding input state by the heralding detectors. Boson sampling is thus performed with random, but heralded, inputs (33, 34).

Because a photonic boson sampling computer does not use adaptive measurements, it falls short of the requirements (6, 7) for a universal quantum computer capable, for example, of factoring integers efficiently (8). On the other hand, its comparatively simple design has prompted a number of small-scale implementations using the interference of three photons injected over different modes in integrated interferometers with up to 13 modes (9–15). First estimates have shown that 30 photons evolving in an interferometer with about 100 modes would already be extremely demanding to simulate classically, providing strong experimental evidence for the quantum computational supremacy. Moreover, boson sampling is an experimental platform suitable for addressing important intermediate challenges for the field of quantum computation, such as benchmarking and certification of medium-scale devices (14–17). There have been recent theoretical investigations on allowable error tolerances (18, 19), as well as a recent proposal for an implementation using phonons in ion traps (20, 21). The technologies enabling a boson sampling computer are useful also for other photonic applications such as quantum cryptography (22) and universal photonic quantum computation (7, 23).

One of the main difficulties in scaling up the complexity of boson sampling devices is the requirement of a reliable source of many indistinguishable photons. Despite recent advances in photon generation (24) using atoms (25), molecules (26, 27), color centers in diamond (28), and quantum dots (29, 30), currently, the most widely used method remains parametric down-conversion (PDC) (31, 32). This approach requires pumping a nonlinear crystal with an intense laser to generate pairs of identical photons. The main advantages of PDC sources are the high photon indistinguishability, collection efficiency, and relatively simple experimental setups. This technique, however, suffers from two drawbacks. First, because the nonlinear process is nondeterministic, so is the photon generation, even though it can be heralded. Second, the laser pump power, and hence the source’s brilliance, has to be kept low to prevent unwanted higher-order terms in the photon generation process. These two characteristics have, so far, restricted PDC implementations of boson sampling experiments to proof-of-principle demonstrations with three photons only in the original spirit of boson sampling (one photon per mode, injected over different modes).

Recently, a new scheme has been proposed to make the best use of PDC sources for photonic boson sampling, greatly enhancing the rate of n-photon events (33, 34). This approach has been named scattershot boson sampling in Aaronson’s blog (34) and involves connecting k (k > n) PDC heralded single-photon sources to different input ports of the interferometer (see Fig. 1B). Suppose each PDC source yields a single photon with probability ϵ per pulse. By pumping all k PDC crystals with simultaneous laser pulses, n photons will be simultaneously generated in a random (but heralded) set of input ports with probability ϵn, which, for k ≫ n, represents an exponential improvement in generation rate with respect to usual, fixed-input boson sampling with n sources. The scattershot boson sampling problem, naturally solvable by this setup, is to sample from the output distribution of a given, random interferometer for random sets of input modes. Note that the pump laser power does not need to be increased k-fold because the laser can sequentially pump each PDC source with very little loss to down-converted photons. In this way, the ratio between one-pair production rate and higher-order terms can be kept low. Another interesting feature of this scheme is the possibility of recording events corresponding to different numbers of injected photons. All these characteristics suggest that the scattershot approach to boson sampling will be decisive in future, larger experiments designed to reach the quantum supremacy regime.

RESULTS

Here, we report experimental results of scattershot boson sampling experiments using a 13-mode integrated photonic chip. We use up to six PDC photon sources to obtain data corresponding to two- and three-photon interference, and validate the device’s functioning using recently proposed statistical tests (14, 17). Additional results on a different nine-mode chip are also presented and certified, thus showing the robustness of the scattershot approach. Finally, we use numerical calculations to discuss the complexity of boson sampling simulation and certification, and to estimate a benchmark for quantum supremacy.

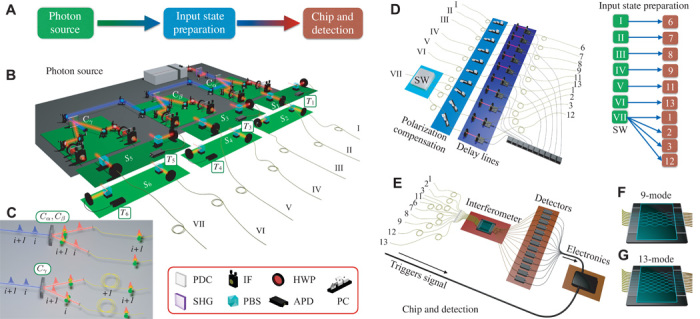

Scattershot boson sampling experiment

A photonic scattershot boson sampling experiment involves a few experimentally demanding steps (see Fig. 2A). First, k > n PDC sources are used to generate n indistinguishable photons in a heralded, but random, set of modes. The input state must then be prepared (introducing time delays and polarization compensation) to be injected into the m-mode integrated interferometer. We must then detect n-fold coincident photon counts at the chip’s output modes, all the while maintaining synchronization so that we have true n-photon interference in the chip. Finally, it is necessary to analyze the output data to validate the correct functioning of the device.

Fig. 2. Experimental layout for the implementation of boson sampling with multiple inputs.

(A) Overall conceptual scheme of the experiment. (B) In each of the three BBO crystals (Cα, Cβ, and Cγ), photon pairs are generated via type II PDC process. The two possible polarization combinations for the two generated photons, HV and VH, constitute two equal PDC sources enfolded in the same crystal, each one exciting a different trigger (photon V) and a different input mode (photon H). The only exception is given by source S2, whose outputs (I and III in the figure) are both injected in the chip. Sources are also time-multiplexed, because pulses generating photons in crystal Cγ are produced before the ones generating photons in Cα and Cβ. (C) Schematic visualization of the six time- and space-multiplexed photon sources; i is an index of the pump pulse number. (D) For the nine-mode device, the input state is varied manually by changing the input fibers. For the 13-mode device, the input state is varied by the multiple source configuration and by the photon switcher, as described in the main text. Top right inset: Map of the connections between sources and interferometer’s inputs. (E) The photons are then injected into the interferometer by means of a single-mode fiber array and then collected at the output via a multimode fiber array, connected to a set of avalanche photodiodes for detection. (F and G) Internal waveguide design of the 9-mode (F) and 13-mode (G) interferometers. Directional couplers have transmittivity = 0.5, whereas the interferometer’s structure presents static phase shifts with a random pattern. SHG, second harmonic generation; HWP, half wave plate; IF, interference filter; PBS, polarizing beam splitter; APD, avalanche photodiode; PC, polarization controller; SW, fiber switcher.

For our experiments, we fabricated two integrated photonic chips implementing random multimode interferometers (with 9 and 13 modes), using a femtosecond laser writing technique (35–38) described in the Methods section. For the nine-mode chip, the input state was created by a four-photon PDC source (crystal Cα in Fig. 2B), with one of the photons used as a trigger. Our preliminary experiment involved simulating the statistics of a scattershot boson sampling experiment in the 9-mode chip by manually connecting 20 different sets of input modes to the source, via a fiber array, and uniformly mixing the data corresponding to different input states.

We used the 13-mode chip to implement scattershot boson sampling experiments with a total of six PDC sources (S1 to S6 in Fig. 2B). We simplified the implementation by enfolding two equal sources in each crystal, corresponding to the two possible vertical/horizontal polarization combinations for the photon pair generated. Hence, the six sources S1 to S6 are created using only the three crystals Cα, Cβ, and Cγ. Each PDC source ideally produces two indistinguishable photons. One such source (source S2) prepares photons I and III, which enter the interferometer in fixed modes 6 and 8, respectively. The other five PDC sources produce random, but heralded, single photons, which are coupled to different input ports of the chip via a polarization correction stage, delay lines, and a single-mode fiber array, according to the map in Fig. 2D. Note that we further increased the input variability by distributing photon VII randomly among four different input ports via an optical fiber switcher with switching rate comparable to the obtained experimental count rate. This raises from five to eight the number of possible input sets, allowing us validation procedure tests on data sampled from a larger number of input-output configurations.

For both chips, the output photons are collected by a multimode fiber array, and multiphoton coincidences are detected by avalanche photodiodes, coordinated by an electronic data acquisition system capable of registering events with an arbitrary number of photons. We then analyzed data corresponding to two- and three-photon interference inside the chip. Synchronizing up to six PDC sources distributed over 10 input modes is a technically difficult step; once that was achieved, the controllable, relative delays between photons allowed us to adjust their degree of distinguishability. Further details about synchronization procedures and indistinguishability between photons of different sources are given in the Supplementary Materials.

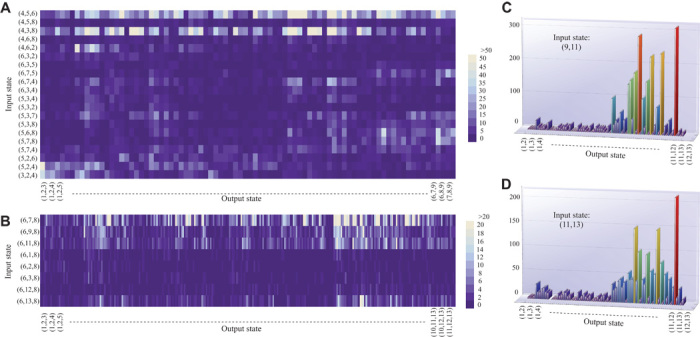

The observed numbers of events corresponding to each input-output combination for the 9- and 13-mode chips are shown in Fig. 3, A and B, respectively. Note the sparseness of the data set, because only a few events corresponding to each input-output combination are observed (if any). This is an expected feature of more complex boson sampling experiments whose number of possible input-output combinations may far exceed the number of observed events. Furthermore, in Fig. 3 (C and D), we show the results for two-photon experiments, in which each input is a doubly heralded two-photon state.

Fig. 3. Multiple input boson sampling in a 9-mode device and scattershot boson sampling in a 13-mode device.

(A) Density plot of the number ni,j of events detected for each of the 1680 input (i) and output (j) combinations used in our boson sampling experiments with the nine-mode chip. (B) Density plot of the number ni,j of events detected for each of the 2288 input (i) and output (j) combinations used in our scattershot boson sampling experiment with the 13-mode chip. (C and D) Number ni,j of events detected for a two-photon scattershot experiment with the 13-mode chip for input states (9,11) (C) and (11,13) (D).

Another route to more complex boson sampling experiments is time multiplexing (39–43), that is, exploiting interference of photons created by different pump pulses on the same PDC source. Ultrafast optical switchers can be used to distribute the photons generated by subsequent pump pulses to different input ports of the photonic chip after suitable synchronization delays. This type of time multiplexing increases the n-photon generation, using a fixed number of PDC sources. Our experiments with the 13-mode chip feature a first proof-of-principle demonstration of interference among photons generated by different pulses. This was done by introducing appropriate delays so that photons from sources S5 and S6 are produced by a different pump pulse than those generated by all the other sources (see Fig. 2C).

Validation of experimental boson sampling data

Unlike problems such as integer factoring, the full certification of the correct functioning of a boson sampling device is by itself a hard computational problem (2, 16, 17, 44, 45). There are, however, statistical tests able to provide partial certification against a number of sensible hypotheses about how the device may be failing to sample from the correct, ideal distribution. Boson sampling thus serves as a useful test bench for the more general problem of quantum device certification. We now discuss the results of the application of validation tests designed for standard boson sampling experiments to our scattershot scenario.

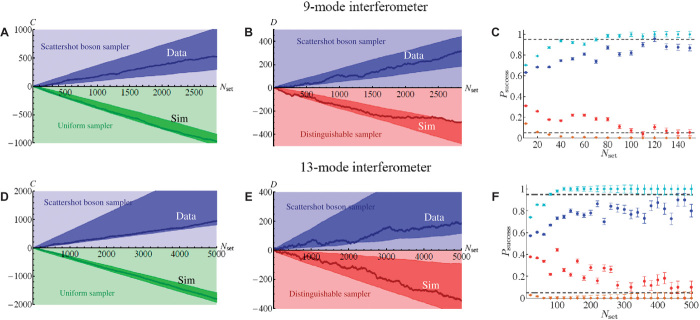

The first test we applied to our data is the scalable statistical test proposed by Aaronson and Arkhipov (17), initially designed to distinguish fixed-input boson sampling events from a uniform distribution over the possible outputs and here extended to the scattershot scenario.

This is achieved by calculating, for each observed event, a discriminator P, which weakly correlates with the boson sampling probability, but which can be calculated efficiently (14). The result for the nine-mode chip is reported in Fig. 4A; at variance with the test performed in (14), instead of a single input, our nine-mode chip experiments allowed for 1680 different input-output combinations. We have also applied the test to data obtained from the 13-mode chip, and the results are reported in Fig. 4D; in this case, there were 2288 different input-output combinations.

Fig. 4. Validation of multiple-input and scattershot boson sampling against various alternative distributions.

(A and D) Application of the Aaronson and Arkhipov test against the uniform distribution (A: for the 9-mode chip; D: for the 13-mode chip). (B and E) Application of the likelihood ratio test against distinguishable sampler (B: for the 9-mode chip; E: for the 13-mode chip). (C and F) Success probability Psuccess of the validation protocol against different alternative distributions as a function of the data set size Nset (C: for the 9-mode chip; F: for the 13-mode chip). Horizontal dashed line: 0.95 and 0.05 thresholds for the success probability Psuccess. (A, B, D, and E) Blue points, scattershot boson sampling experimental data; green points, numerical simulation of a uniform sampler; red points, numerical simulation of distinguishable sampler data; dark blue areas, ±2σ region (A and D) or ±1σ region (B and E) expected for the experimental scattershot data, obtained from a numerical simulation, which includes noise in the implemented unitary corresponding to the fabrication tolerances; dark green areas, ±2σ region expected for the uniform sampler; dark red areas, ±1σ region expected for the distinguishable sampler. (C and F) Cyan points, scattershot boson sampling experimental data against the uniform sampler with the Aaronson-Arkhipov test; blue points, scattershot boson sampling experimental data against the distinguishable sampler; orange points, numerical simulation of uniform sampler data against scattershot boson sampler; red points, numerical simulation of distinguishable sampler data against the scattershot boson sampler.

A second test we performed is an adaptation of a standard likelihood ratio test (46), with the goal of comparing our experimental data with those expected if distinguishable photons were used. For each experimental outcome, the probabilities for indistinguishable and distinguishable photons are compared (more details on the tests are reported in Methods and in the Supplementary Materials). The results of this test for the 9- and 13-mode chips are shown in Fig. 4, B and E, respectively. Note that, again, in both cases, we applied the test to the data set combining all different input states used.

Successful validation could be obtained even with small data sets. This is highlighted in Fig. 4C for the 9-mode chip and in Fig. 4F for the 13-mode chip, where we plot the trend of the test’s success rate against the size of the data set used.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have reported the first experimental implementation of the scattershot approach to photonic boson sampling, recently proposed in (33, 34), a promising way of exponentially scaling up the computational power of the quantum sampler. Our experiments use six PDC sources in parallel to demonstrate the feasibility of nontrivial realizations of this approach. In the experimental implementation, because of non-optimal beam propagation and PDC sources, we observed an increase in the event rate by a factor of 4.5 (3.4) compared to standard boson sampling with a source of average (best) brightness. This value should be compared to the expected value of 5.

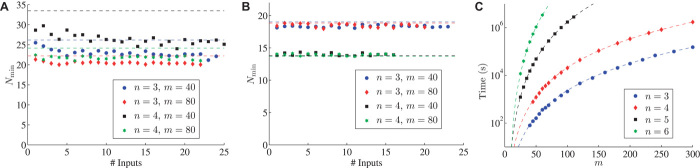

Let us now discuss how scattershot boson sampling may bring within reach an experimental regime approaching quantum supremacy. Let us consider experiments with N = 2000 events, more than sufficient to perform a successful validation of the scattershot boson sampler (see Fig. 5, A and B). In this regime, with high probability, each recorded event is sampled from a different input state, provided that , and assuming the use of one PDC source per input mode. To get an insight into the hardness of calculating the whole output distribution corresponding to each input used, we illustrate the required computational time on a standard laptop in Fig. 5C. Although this brute force calculation is currently the only reported approach for a classical boson sampling simulation, it is likely that more efficient classical sampling algorithms are possible for interferometers chosen uniformly at random, but no description of those has yet been reported in the literature.

Fig. 5. Full simulation of scattershot boson sampling and of its validation.

(A) Minimum data set size to obtain 95% success probability for the validation of scattershot boson sampling data against the uniform sampler as a function of the number of input states, adopting the Aaronson and Arkhipov test. (B) Minimum data set size to obtain 95% success probability for the validation of a scattershot boson sampling experiment against the distinguishable sampler as a function of the number of input states, adopting the likelihood ratio test. (C) Time required with a laptop to calculate N = 2000 boson sampling probability distributions, each one corresponding to a different input configuration, as a function of the number of modes m, for different number of photons n.

The main advantage of the scattershot approach is to markedly decrease the experimental run time with respect to the usual, fixed-input boson sampling setup. Using challenging but feasible experimental parameters for pulse rate (80 MHz), per-pulse generation probability (0.015), triggering efficiency (0.5), and overall photon counting probability (0.15, which takes into account both photon losses in the injection-propagation stage, linearly dependent from the chip size, and detector inefficiencies), we get an estimated run time of ~107 to 108 s for a 2000-event, fixed-input boson sampling experiment with n = 4, m = 100. The corresponding scattershot boson sampling experiment uses k = 100 PDC sources in parallel, resulting in a quantum run time of ~50 s. These estimates clearly illustrate the boost in computational speed provided by the scattershot approach.

Validation of the scattershot boson sampler would still be feasible well into the quantum supremacy regime, because the number of events whose probabilities need to be calculated by a classical computer to certify the proper operation of the quantum device is very low and almost independent of the number of photons and modes involved (see Fig. 5, A and B). This is expected to hold for validation of experiments with up to about 30 photons.

Note that the simulations of Fig. 5 did not take into account errors such as partial photon distinguishability and other experimental imperfections. In larger devices, for example, a spurious but genuine-looking event could result from the loss of l < n triggered photons and simultaneous injection of l untriggered photons. A precise analysis of the effect of incorrectly heralded photons in our experiments is carried out in the Supplementary Materials. These events count as white noise in the validation tests, slightly lowering the test’s efficiency. This particular problem can be overcome by using the heralding detectors to briefly open an optical shutter in the corresponding input mode, as discussed in the Supplementary Materials.

Other photon source schemes, such as collecting larger number of modes from degenerate PDC type I radiation via microlenses (47), as well as novel approaches using time-bin encoding (48), are all promising routes to scale up the complexity of future boson sampling experiments. Further theoretical progresses could also help in this endeavor, such as the development of scalable statistical validation tests against other alternative distributions. Recent proposals along these lines are based on looking at global coalescence effects (15), checking specific output suppressions in interferometers with certain symmetries (45) or performing single-mode homodyne detection (44). Moreover, it has been argued that there are other classes of quantum states that can be used for boson sampling without spoiling its computational complexity (49, 50); future research in this direction could help to simplify the experimental implementation of hard-to-simulate devices.

METHODS

Fabrication of integrated optics devices

Multimode integrated interferometers are fabricated in Eagle2000 (Corning) alumino-borosilicate glass by femtosecond laser direct-writing. Focused ultrashort pulses induce permanent refractive index changes in the focal volume by nonlinear absorption mechanisms. Buried waveguides are directly drawn in the volume of the glass by suitably translating the sample with respect to the writing beam. This direct-write technique allows fast realization of custom integrated optical circuits with large design freedom. A cavity dumped Yb:KYW mode-locked oscillator, producing laser pulses with ~300-fs duration, 1-MHz repetition rate, and 1030-nm wavelength, is used. In particular, irradiation is performed by focusing 220-nJ pulses with a 0.6–numerical aperture microscope objective and by translating the sample at a constant speed of 40 mm/s to obtain single-mode waveguides for 785-nm photons. Average waveguide depth below the sample surface is 170 μm. Interferometers implementing random unitary matrices are obtained by cascading several rows of balanced (50:50) directional couplers, with the layouts in Fig. 2 (F and G), connected by S-bends of slightly different lengths, which induce controlled (though randomly chosen) phase shifts (12). Each directional coupler (including S-bends) is about 5 mm long, whereas input and output waveguides are 127 μm spaced, for a global footprint of the circuits of about 35 mm × 1.1 mm for the 9-mode device and 45 mm × 1.6 mm for the 13-mode device.

Experimental details

Single photons were generated in six equal PDC sources, implemented in three crystals. The three-photon input state for the nine-mode chip was obtained by PDC generation from the first crystal, with one of the four emitted photons used as a trigger. The input states were then changed manually by connecting a fiber array to 20 different sets of input modes of the chip. The 13-mode chip was then used to implement the complete scattershot version of the boson sampling experiment. The three crystals reproduced six PDC sources: The first one belonging to the first crystal was adopted to inject two fixed input modes of the chip (numbers 6 and 8), whereas another photon was injected shot by shot coming from one of the five remaining PDC sources. At the output of both chips, multimode fibers were connected to single-photon counting detectors and an electronic data acquisition system allowed to register events with an arbitrary number of photons.

Validation of the experimental data

The validation against the hypothesis that the data are sampled according to a uniform distribution is performed by adopting the scalable Aaronson and Arkhipov test (17) experimentally verified in Spagnolo et al. The validation test against the hypothesis that the data are sampled with distinguishable photons works as follows. For each experimental outcome i, the certifier calculates the associated probabilities for indistinguishable photons and for distinguishable photons. A counter variable D is increased (decreased) by 1 if . After analyzing all events, D > 0 (D < 0) indicates that the hypothesis of indistinguishable (distinguishable) photons is more likely to hold. The probabilities pi and qi are calculated using the permanent formula, taking into account the partial photon distinguishability of the source and the chip’s theoretical design parameters. For the nine-mode interferometer, the data were collected separately by manually changing the input state. Then, the recorded events before the validation procedure are mixed uniformly to represent a set of data collected with a random input state.

The same validation procedure was carried out for the two-photon data, which were collected simultaneously to the three-photon ones. In particular, photons from inputs 11 and 13 are generated from two different laser pulses. We obtained an average success probability Psuccess >95% of the validation process after a data set size of Nset ~150 against the uniform distribution and of Nset ~50 against the distribution with distinguishable photons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge extremely useful and stimulating discussion with S. Aaronson. We acknowledge technical support from S. Giacomini and G. Milani. Funding: This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant 3D-QUEST (3D-Quantum Integrated Optical Simulation; grant agreement no. 307783): http://www.3dquest.eu, by the PRIN project Advanced Quantum Simulation and Metrology (AQUASIM), by the H2020-FETPROACT-2014 Grant QUCHIP (Quantum Simulation on a Photonic Chip; grant agreement no. 641039), by the Brazilian National Institute for Science and Technology of Quantum Information (INCT-IQ/CNPq), and by the project of Ateneo Sapienza award: PhotoAnderson. D.J.B. was supported in part by Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Author contributions: M.B., N.S., C.V., F.F., P.M., E.F.G., R.O., and F.S. conceived the experimental implementation of the scattershot boson sampling. A.C., R.R., and R.O. fabricated and characterized the integrated devices using classical optics. C.V., M.B., N.S., F.F., N.V., and F.S. carried out the quantum experiments. N.S., M.B., C.V., F.F., and F.S. elaborated the data. N.S., M.B., L.L., C.V., F.F., D.J.B., E.F.G., and F.S. carried out the numerical simulation. All the authors discussed the experimental implementation and results, and contributed to writing the paper.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/3/e1400255/DC1

Fig. S1. Characterization of the sources photon indistinguishability by Hong-Ou-Mandel interference in a symmetric beam splitter.

Fig. S2. Synchronization of single photons belonging to the same source obtained by PDC.

Fig. S3. Scheme to exploit stimulated emission for the synchronization of photons generated from different crystals.

Fig. S4. Synchronization of single photons belonging to different sources obtained by amplification of coherent states.

Fig. S5. Dependence of the variation distance d as a function of the sample size.

Fig. S6. Contour plot of distribution of pairs [d(data, A), d(data, B)] of variation distances between the output distribution associated with an incorrectly heralded event and either the hypothesis of correct heralded input (A) or the hypothesis of correct input but using distinguishable photons (B).

Fig. S7. Numerical simulation of a validation test of simulated experimental data against the hypotheses of correct boson sampling data (D > 0), and the hypothesis that photons are distinguishable (D < 0).

Fig. S8. Ratio between the per-pulse probability of detecting three photons in the trigger apparatus and three photons after the chip without shutters and with shutters, as a function of the number m of sources and modes (g = 0.1, ηT = 0.2, ηD = 0.015).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.J. Preskill, Quantum computing and the entanglement frontier, Proceedings of 25th Solvay Conference on Physics “The Theory of the Quantum World”, Brussels, 19 to 22 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.S. Aaronson, A. Arkhipov, The Computational Complexity of Linear Optics. In Proceedings of the 43rd annual ACM symposium on Theory of Computing, San Jose, 2011 (ACM Press, New York, 2011), pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valiant L. G., The complexity of computing the permanent. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 8, 189–201 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 4.L. Troyansky, N. Tishby, Permanent uncertainty: On the quantum evaluation of the determinant and the permanent of a matrix, in Proceedings of Physics and Computation (PhysComp 96), Boston, MA, 22 to 24 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.S. Scheel, Permanents in linear optical networks, arXiv:quant-ph/0406127 (2004).

- 6.Ladd T. D., Jelezko F., Laflamme R., Nakamura Y., Monroe C., O’Brien J. L., Quantum computers. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knill E., Laflamme R., Milburn G. J., A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature 409, 46–52 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shor P. W., Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1484–1509 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broome M. A., Fedrizzi A., Rahimi-Keshari S., Dove J., Aaronson S., Ralph T. C., White A. G., Photonic boson sampling in a tunable circuit. Science 339, 794–798 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spring J. B., Metcalf B. J., Humphreys P. C., Kolthammer W. S., Jin X.-M., Barbieri M., Datta A.. Thomas-Peter N., Langford N. K., Kundys D., Gates J. C., Smith B. J., Smith P. G. R., Walmsley I. A., Boson sampling on a photonic chip. Science 339, 798–801 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tillmann M., Dakic B., Heilmann R., Nolte S., Szameit A., Walther P., Experimental boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 7, 540–544 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crespi A., Osellame R., Ramponi R., Brod D. J., Galvão E. F., Spagnolo N., Vitelli C., Maiorino E., Mataloni P., Sciarrino F., Integrated multimode interferometers with arbitrary designs for photonic boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 7, 545–549 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spagnolo N., Vitelli C., Sansoni L., Maiorino E., Mataloni P., Sciarrino F., Brod D. J., Galvão E. F., Crespi A., Ramponi R., Osellame R., General rules for bosonic bunching in multimode interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 130503 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spagnolo N., Vitelli C., Bentivegna M., Brod D. J., Crespi A., Flamini F., Giacomini S., Milani G., Ramponi R., Mataloni P., Osellame R., Galvão E. F., Sciarrino F., Experimental validation of photonic boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 8, 615–620 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carolan J., Meinecke J. D. A., Shadbolt P. J., Russell N. J., Ismail N., Worhoff K., Rudolph T., Thompson M. G., O’Brien J. L., Matthews J. C. F., Laing A., On the experimental verification of quantum complexity in linear optics. Nat. Photon. 8, 621–626 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.C. Gogolin, M. Kliesch, L. Aolita, J. Eisert, Boson-sampling in the light of sample complexity, arXiv:1306.3995v2 (2013).

- 17.Aaronson S., Arkhipov A., Bosonsampling is far from uniform. Quantum Inf. Comput. 14, 1383–1423 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohde P. P., Ralph T. C., Error tolerance of the boson-sampling model for linear optics quantum computing. Phys. Rev. A 85, 022332 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leverrier A., Garcia-Patron R., Analysis of circuit imperfections in BosonSampling. Quantum Inf. Comput. 15, 0489–0512 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau H., James D., Proposal for a scalable universal bosonic simulator using individually trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 85, 062329 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen C., Zhang Z., Duan L.-M., Scalable implementation of boson sampling with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 050504 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gisin N., Ribordy G., Tittel W., Zbinden H., Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kok P., Munro W. J., Nemoto K., Ralph T. C., Dowling J. P., Milburn G. J., Linear optical quantum computing with photonic qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 135–174 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisaman M. D., Fam J., Migdall A., Polyakov S. V., Invited review article: Single-photon sources and detectors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 071101 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hijlkema M., Weber B., Specht H. P., Webster S. C., Kuhn A., Rempe G., A single-photon server with just one atom. Nat. Phys. 3, 253–255 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner M., Hartschuh A., Korlacki R., Meixner A. J., Highly efficient, tunable single photon source based on single molecules. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 183122 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lettow R., Rezus Y. L. A., Renn A., Zumofen G., Ikonen E., Götzinger S., San-doghdar V., Quantum interference of tunably indistinguishable photons from remote organic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 123605 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtsiefer C., Mayer S., Zarda P., Weinfurter H., Stable solid-state source of single photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 290–293 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields A. J., Semiconductor quantum light sources. Nat Photon 1, 215–223 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauf S., Stoltz N. G., Rakher M. T., Coldren L. A., Petroff P. M., Bouwmeester D., High-frequency single-photon source with polarization control. Nat Photon 1, 704–708 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnham D. C., Weinberg D. L., Observation of simultaneity in parametric production of optical photon pairs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 25, 84–87 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 32.P.Kwiat, Mattle K., Weinfurter H., Zeilinger A., New high-intensity source of polarization-entangled photon pairs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4337–4341 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lund A. P., Laing A., Rahimi-Keshari S., Rudolph T., J. L. O’Brien, Ralph T. C., Boson sampling from a Gaussian state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 100502 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.S. Aaronson, Scattershot BosonSampling: A new approach to scalable BosonSampling experiments. Shtetl-Optimized, 2013; http://www.scottaaronson.com/blog/?p=1579

- 35.Gattass R.R., Mazur E., Femtosecond laser micromachining in transparent materials. Nat. Photon. 2, 4–219 (225). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall G. D., Politi A., Matthews J. C. F., Dekker P., Ams M., Withford M. J., O’Brien J. L., Laser written waveguide photonic quantum circuits. Opt. Express 17, 12546–12554 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrielli G., Crespi A., Geremia R., Ramponi R., Sansoni L., Santinelli A., Mataloni P., Sciarrino F., Osellame R., Rotated waveplates in integrated waveguide optics. Nat. Commun. 5, 4249 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heilmann R., Gräfe M., Nolte S., Szameit A., Arbitrary photonic wave plate operations on chip: Realizing Hadamard, Pauli-X, and rotation gates for polarisation qubits. Sci. Rep. 4, 4118 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittman T. B., Jacobs B. C., Franson J. D., Single photons on pseudodemand from stored parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rev. A 66, 042303 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeffrey E., Peters N. A, Kwiat P. G, Towards a periodic deterministic source of arbitrary single-photon states. New J. Phys. 6, 100 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Migdall A. L., Branning D., Castelletto S., Tailoring single-photon and multiphoton probabilities of a single-photon on-demand source. Phys. Rev. A 66 053805 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCusker K. T., Kwiat P. G., Efficient optical quantum state engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 163602 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma X., Zotter S., Kofler J., Jennewein T., Zeilinger A., Experimental generation of single photons via active multiplexing. Phys. Rev. A 83, 043814 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.L. Aolita, C. Gogolin, M. Kliesch, J. Eisert, Reliable quantum certification for photonic quantum technologies, arXiv:1407.4817v2 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Tichy M. C., Mayer K., Buchleitner A., Mølmer K., Stringent and efficient assessment of boson-sampling devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020502 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.T. M. Cover, J. A. Thomas, Elements of Information Theory (Wiley-Interscience, New York, ed. 2, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi A., Vallone G., Chiuri A., De Martini F., Mataloni P., Multipath entanglement of two photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 153902 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Motes K. R., Gilchrist A., Dowling J. P., Rohde P.P., Scalable boson sampling with time-bin encoding using a loop-based architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 120501 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohde P. P., Motes K. R., Knott P., Fitzsimons J., Munro W., Dowling J. P., Evidence for the conjecture that sampling generalized cat states with linear optics is hard. Phys. Rev. A 91, 012342 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seshadreesan K. P., Olson J. P., Motes K. R., Rohde P. P., Dowling J. P., Boson sampling with displaced single-photon Fock states versus single-photon-added coherent states: The quantum-classical divide and computational-complexity transitions in linear optics. Phys. Rev. A 91, 022334 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong C., Ou Z., Mandel L., Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2044–2046 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Martini F., Sciarrino F., Non-linear parametric processes in quantum information. Prog. Quantum Electron. 29, 165–256 (2005). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/3/e1400255/DC1

Fig. S1. Characterization of the sources photon indistinguishability by Hong-Ou-Mandel interference in a symmetric beam splitter.

Fig. S2. Synchronization of single photons belonging to the same source obtained by PDC.

Fig. S3. Scheme to exploit stimulated emission for the synchronization of photons generated from different crystals.

Fig. S4. Synchronization of single photons belonging to different sources obtained by amplification of coherent states.

Fig. S5. Dependence of the variation distance d as a function of the sample size.

Fig. S6. Contour plot of distribution of pairs [d(data, A), d(data, B)] of variation distances between the output distribution associated with an incorrectly heralded event and either the hypothesis of correct heralded input (A) or the hypothesis of correct input but using distinguishable photons (B).

Fig. S7. Numerical simulation of a validation test of simulated experimental data against the hypotheses of correct boson sampling data (D > 0), and the hypothesis that photons are distinguishable (D < 0).

Fig. S8. Ratio between the per-pulse probability of detecting three photons in the trigger apparatus and three photons after the chip without shutters and with shutters, as a function of the number m of sources and modes (g = 0.1, ηT = 0.2, ηD = 0.015).