Finding the silent skipped beat: Predicting arrhythmia-causing drugs using a high-throughput hybrid heart simulator.

Keywords: Heart Simulator, drug screening, Cardiotoxicity, finite element method, Torsade de pointes

Abstract

To save time and cost for drug discovery, a paradigm shift in cardiotoxicity testing is required. We introduce a novel screening system for drug-induced arrhythmogenic risk that combines in vitro pharmacological assays and a multiscale heart simulator. For 12 drugs reported to have varying cardiotoxicity risks, dose-inhibition curves were determined for six ion channels using automated patch clamp systems. By manipulating the channel models implemented in a heart simulator consisting of more than 20 million myocyte models, we simulated a standard electrocardiogram (ECG) under various doses of drugs. When the drug concentrations were increased from therapeutic levels, each drug induced a concentration-dependent characteristic type of ventricular arrhythmia, whereas no arrhythmias were observed at any dose with drugs known to be safe. We have shown that our system combining in vitro and in silico technologies can predict drug-induced arrhythmogenic risk reliably and efficiently.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrhythmias are serious side effects of commonly used drugs. Torsade de Pointes (TdP) is a rare but potentially lethal type of ventricular arrhythmia often caused by inhibition of the repolarizing potassium current of cardiac myocytes (1). The historical incidence of drug-related sudden cardiac death led to the establishment of regulatory requirements for cardiotoxicity testing, which include the measurement of repolarizing potassium current through hERG potassium current, an in vivo QT assay in an animal model, and the examination of QT interval in healthy volunteers (a thorough QT study) in 2005 (2). The practice of these guidelines has been successful in preventing arrhythmia-related accidents. However, pharmaceutical companies, regulatory agencies, and academic institutions all recognize the limitations of these costly tests in accurately predicting the arrhythmogenic risk. Accordingly, in 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and related organizations presented a drastic paradigm shift in cardiotoxicity testing (3–5). This proposal is based on incorporation of novel technologies involving computational integration of multiple ion channel assays using cell models of cardiac electrophysiology and electrophysiological tests of stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes. Indeed, in silico assessment of the arrhythmogenic risk has been widely attempted using various types of cell or tissue models of cardiac electrophysiology. However, most of these studies only provide surrogate markers of arrhythmia such as action potential duration, QT prolongation of pseudo-electrocardiogram (ECG), and QT dispersion, rather than the occurrence of clinically observed TdP (6–8). Although development of a standardized method is scheduled for 2016, herein we present the results of a novel assay system using our multiscale, multiphysics heart simulation technology coupled with multi-ion current assays developed on expressed human ion channels (Fig. 1).

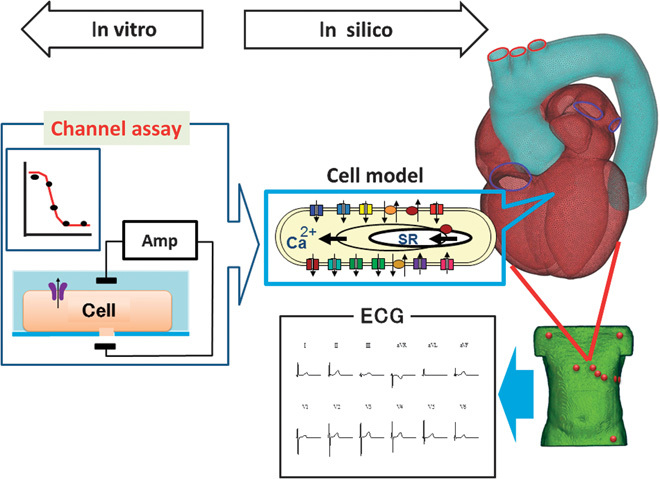

Fig. 1. Diagram of the assay system.

Dose-inhibition curves of drugs were determined for six ion channels from in vitro experiments using the automated patch clamp system. On the basis of these data, conditions of the in silico heart model under specific drug concentrations were simulated by modulating the channel parameters in cell models of cardiac electrophysiology to yield the 12-lead ECG.

Our heart simulator, UT-Heart, is a finite element method (FEM)–based human heart model that can reproduce all fundamental activities of the working heart, including propagation of excitation, contraction and relaxation, and generation of blood pressure and flow, based on the molecular mechanisms of excitation-contraction coupling (9–13). For the detailed analysis of ECG, we coupled the heart model with the FEM model of the human torso and solved the bidomain equations with a novel solving technique (14, 15). This feature of the system may potentially replace the thorough QT assay beyond the limits of cell models of electrophysiology.

As benchmark test chemicals, we selected the following 12 drugs recognized to have varying degrees of TdP risk: quinidine, d,l-sotalol, amiodarone, E-4031, cisapride, astemizole, terfenadine, bepridil, moxifloxacin, verapamil, dofetilide, and ranolazine (7, 16, 17). Pharmacological characterization of these drugs was made by measuring their inhibitory effects on the following six ion currents/channels expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells over a wide range of concentrations: rapid delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr/hERG), sodium current (INa/Nav1.5), L-type calcium current (ICa/Cav1.2), slow delayed rectifier current (IKs/KCNQ1 + KCNE1), inward rectifier potassium current (IK1/Kir2.1), and transient outward current (Ito/Kv4.3 + KChIP2). The effect of the drugs under various plasma concentrations was reproduced by changing the parameters of each channel model in the heart simulator according to the obtained dose-inhibition relationship. The list of abbreviation is shown in table S2.

RESULTS

Characterization of drugs

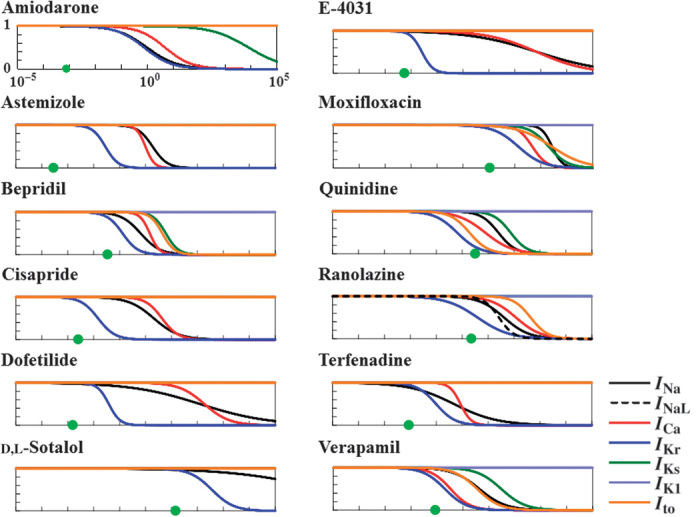

The results of the in vitro evaluation of the inhibitory effects of 12 drugs on six ion currents tested are summarized in Fig. 2 (see also table S1 for detail). Median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values normalized by the free effective therapeutic plasma concentration (ETPCunbound) varied considerably among the drugs; for hERG channels, the hERG IC50/ETPCunbound ranged from 0.197 (quinidine) to 975 (amiodarone). In the following in silico drug testing, we simulated cases in which the heart is exposed to each drug at concentrations 0 (control), 1, 3, 5, 10, 30, 50, 100, 300, 500, and 1000 times of ETPCunbound. If the arrhythmia event occurred, we also tested the concentration between these levels to narrow down the arrhythmia threshold.

Fig. 2. Dose-inhibition relation of drugs on ion currents.

Left column (top to bottom): amiodarone, astemizole, bepridil, cisapride, dofetilide, and d-sotalol. Right column (top to bottom): E-4031, moxifloxacin, quinidine, ranolazine, terfenadine, and verapamil. In each graph, relative activities of ion currents are plotted as a function of drug concentration in logarithmic scale. Black line, INa; black dotted line, INaL; red line, ICa; dark blue line, IKr; green line, IKs; light blue line, IK1; orange line, Ito; green circle, ETPCunbound.

In silico preclinical analysis of cardiotoxicity

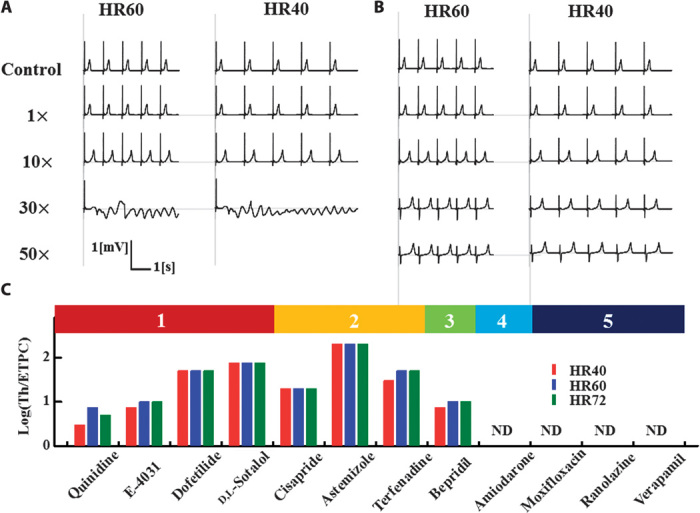

Drug effects at each specific dose were simulated by introducing the current inhibition of six channels to all the cell models (22,750,008 cells modeled) included in the heart simulator. Simulations were performed by coupling the heart model with the torso at either 1 Hz [60 beats per minute (bpm)] or 2/3 Hz (40 bpm) to reflect the standard 12-lead ECG used for the thorough QT test (Fig. 1, movie S1, and fig. S1). The simulation results at 1.2 Hz (72 bpm) are also available in fig. S2. Cisapride is a drug used for the treatment of dyspepsia and was withdrawn from the market because of the risk of TdP (16). When this drug was applied to the model, the QT interval was prolonged in a dose-dependent manner, and TdP was observed at 30 times of ETPCunbound [Fig. 3A, heart rate (HR) = 60 bpm (left) and 40 bpm (right)]. By contrast, verapamil, which is recognized as a safe drug with no published reports of TdP in humans (16), exhibited a similar, dose-dependent QT interval prolongation, but never induced TdP even at 50 times ETPCunbound [Fig. 3B, HR = 60 bpm (left) and 40 bpm (right)]. Above this dose (100 times ETPCunbound), the membrane excitation did not propagate owing to the inhibition of Na current. The arrhythmogenic thresholds of the 12 drugs at both HRs are shown in Fig. 3C (the ECG responses of the 12 drugs are shown in fig. S2). We did not observe TdP even at higher doses for amiodarone, moxifloxacin, or verapamil.

Fig. 3. In silico risk assessment of drug-induced arrhythmogenesis.

(A and B) Two-lead ECGs with varying doses of drugs (control, 1×, 10×, 30×, 50× of ETPCunbound) are shown for cisapride (A) and verapamil (B) at HR = 40 bpm (left column) and HR = 60 bpm (right column). For both drugs, a dose-dependent prolongation of QT intervals was observed, although TdP was only observed for cisapride. (C) Threshold values relative to ETPCunbound are shown for each drug categorized as high risk (1, 2, and 3) or safe (4 and 5). TdP was not observed for drugs in categories 4 and 5. ND, not detected.

We evaluated the predictability of our simulation by comparing the obtained TdP threshold values with the actual risk reported in the literature. For this purpose, we used the risk categories by Redfern and Lawrence (7, 16, 17) with three modifications. First, E-4031, which is not included in these studies, was categorized as 1 because it is a pure hERG blocker developed as an anti-arrhythmic drug, although a proarrhythmic effect has also been reported (movie S2 and fig. S1B) (18). Second, ranolazine, which was also not included in these studies, was categorized as 5 according to the literature (19). Third, we recategorized amiodarone as 4 (drugs for which there have been isolated reports of TdP in humans) because the incidence of TdP is quite low for this drug in clinical trials (20). Further, a meta-analysis on 6500 patients revealed that the prophylactic use of amiodarone reduces the risk of arrhythmia/sudden cardiac death in high-risk patients with recent myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure (21). Amiodarone was excluded from the list of category 1 drugs by Lawrence et al. (17), whereas in the analysis by Mirams et al. (7), amiodarone was the only drug that resulted in a large prediction error (false negative). Finally, although we are also aware of recent reports of arrhythmogenicity of moxifloxacin, we used the original categorization by Redfern and Lawrence in this study (16, 17). The threshold values relative to ETPCunbound are shown for each drug in each category in Fig. 3C. The threshold values did not differ appreciably between the three HR, although TdP was induced at lower threshold values by some drugs, reproducing the reported arrhythmogenic risk of bradycardia by prolongation of ventricular repolarization (1). Although the number of drugs tested was small, all drugs in categories 1 and 2 have relatively low threshold values. Most importantly, TdP was not observed with drugs in categories 4 and 5. Thus, our analysis produced no false positives.

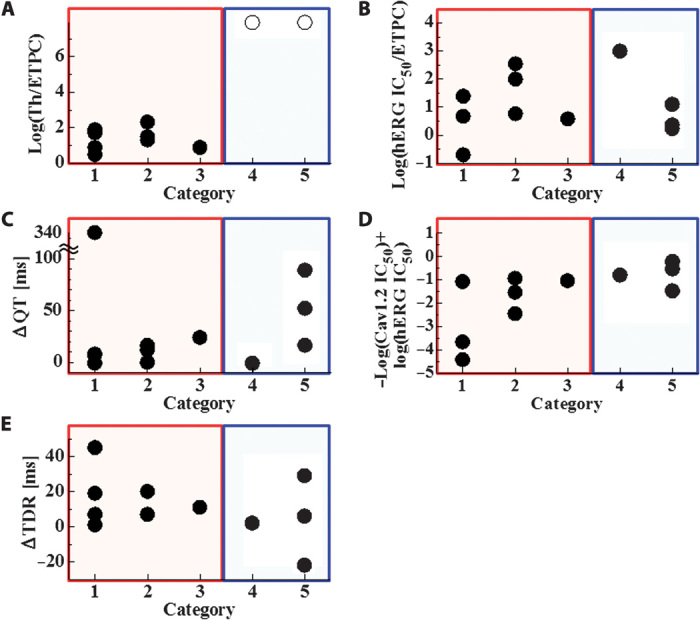

Comparison with other biomarkers for TdP risk

Because the multiscale simulation provides us with various parameters from the molecular to the organ level simultaneously, we compared the predictability of the present method (Fig. 4A) with other biomarkers including hERG IC50 (Fig. 4B), corresponding to the hERG test, and QT interval prolongation (Fig. 4C), corresponding to the thorough QT test, both recommended in the current guidelines. We also examined the MICE model that compares the inhibitory effects of a drug on the major depolarizing current ICa/Cav1.2 and repolarizing current IKr/hERG during the action potential plateau (22) [Fig. 4D, evaluated as −log(Cav1.2 IC50) + log(hERG IC50)], as well as the transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) (Fig. 4E). TDR was measured by the difference between the maximum and minimum action potential durations under maximum tolerable concentration without arrhythmia. Simulations were performed at HR = 60 bpm. In clear contrast to the present method, the hERG IC50, QT interval prolongation, the MICE model (22), and TDR could not discriminate the low-risk drugs (categories 4 and 5: blue rectangle) from the high-risk drugs (categories 1 to 3: red rectangle).

Fig. 4. Comparison of the predictability of currently proposed biomarkers for arrhythmogenic risk for drugs in each category.

(A) Threshold (Th) for TdP (current method). For drugs not inducing TdP, an ○ value is assigned at HR = 60. (B) hERG inhibition quantified by hERG IC50/ETPCunbound. (C) Prolongation of QT interval at the ETPC. (D) MICE model evaluated as −log(Cav1.2 IC50) + log(hERG IC50). d,l-Sotalol was not evaluated for the MICE model because Cav1.2 IC50 could not be identified. (E) TDR measured by the difference between maximum and minimum action potential durations under maximum tolerable concentration without arrhythmia. Concentrations are 100 (amiodarone), 100 (astemizole), 5 (bepridil), 10 (cisapride), 30 (dofetilide), 50 (d,l-sotalol), 5 (E-4031), 100 (moxifloxacin), 1 (quinidine), 20 (ranolazine), 10 (terfenadine), and 50 (verapamil) times ETPC. Except for the present method, values of biomarkers were distributed evenly among the categories.

Sensitivity analysis

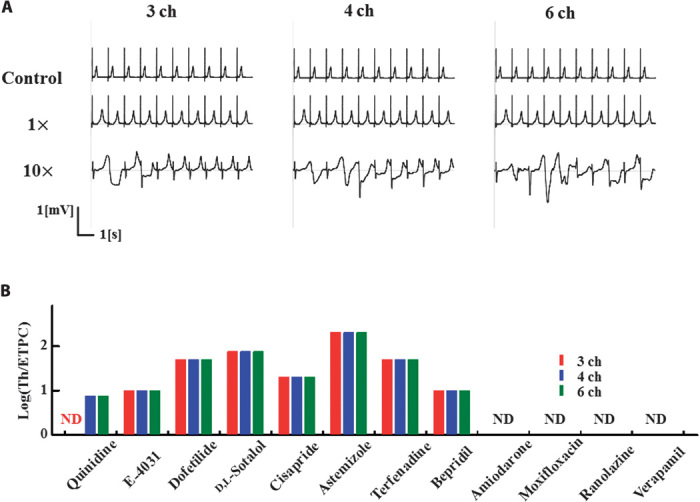

Although the automated patch clamp technique coupled with the in vitro ion channel expression system has enabled the high-throughput screening of drug toxicity, multiple channel assays are still time-consuming and expensive. Accordingly, we examined how the reduction in the number of analyzed channels affects the predictability for TdP risk. We repeated the simulations using the results for four channels (IKr/hERG, INa/Nav1.5, ICa/Cav1.2, and IKs/KCNQ1 + KCNE1) and three channels (IKr/hERG, INa/Nav1.5, and ICa/Cav1.2), and compared the results with those using six channels. In Fig. 5B, the obtained threshold values were compared among the simulations using a different number of channels. We found that a reduction in the number of channels from six to four did not alter the TdP threshold for any of the drugs tested. However, a further reduction to three channels disabled the detection of TdP for quinidine (Fig. 5A). Thus, at least for the drugs tested in this study, assays on four channels are necessary.

Fig. 5. Effect of the number of channels assayed on risk prediction.

(A) Drug effect of quinidine on ECG simulated using the data on six (left), four (middle), and three (right) channels (ch). When using the data on only three channels, arrhythmogenicity was not reproduced. (B) Relative threshold values for TdP of each drug examined using the data on three (red), four (blue), and six (black) channels. A difference was detected in quinidine.

Next, we assessed the efficacy of the six channels assayed in this study for accurate risk assessment. We tested the TdP risk of hypothetical multichannel blockers created by adding 50% inhibition of the five ion currents not investigated in this analysis one by one to the pharmacological characteristics of verapamil under 50 times ETPCunbound. We also examined the effect of IK1 inhibition because none of the drugs tested in this study displayed an inhibitory action on this channel. We found that the addition of IK1 inhibition introduced a minor rhythm disturbance (fig. S3), confirming the significance of assaying this channel. Together, for high-throughput screening of TdP risk, combinations of four to six of the channels selected in this study are recommended, depending on the affordability and time. Of course, inclusion of other ion currents mediated by sodium/potassium pumps, calcium pumps, and sodium-calcium exchangers would potentiate the power of predictability.

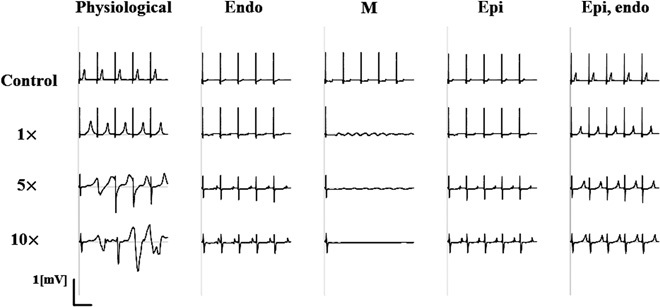

Importance of realistic, three-dimensional simulation

In the analysis presented above, inclusion of IKs inhibition (switch from three-channel effects to four-channel effects, Fig. 5) caused TdP by quinidine at as low as 7.5 times ETPCunbound, although the inhibitory effect at this concentration (about 30% of IKs IC50) was at most 20%. Of course, the interplay with other ion currents plays a significant role. However, we hypothesized that the inhibition of the IKs channel could amplify the TDR originating from the heterogeneous expression of this channel species to increase the TdP propensity (23). To test this hypothesis, we repeated the simulation with the heart model in which the whole ventricles consisted of either epicardial, midmyocardial (M), or endocardial cells, as well as with the two-layered model consisting of epicardial and endocardial cells. As shown in Fig. 6, TdP was not observed in those models with nonphysiological cell distributions, whereas with homogeneous distributions, especially in the model with M cells, sustained depolarization was observed. Sustained depolarization is caused by early after depolarization, which is a sign of arrhythmia. However, its appearance at ETPCunbound does not recapitulate the real risk of this drug. Together, these data suggest that only the three-dimensional heart simulation with physiological cell distribution enables the accurate prediction of TdP risk, whereas risk assessment based on only the cell model of electrophysiology may be misleading.

Fig. 6. Significance of the three-dimensional heart model with realistic tissue structure for the accurate prediction of arrhythmogenic risk.

Effects of varying doses of quinidine up to 10 times of ETPCunbound on ECG were evaluated using the model with three types of ventricular myocytes (endocardial, M, and epicardial cells) arranged transmurally (physiological), endocardial cell only (endo), M cell only (M), epicardial cell only (epi), and two-layered model with epicardial and endocardial cells (epi, endo). Arrhythmia was observed only in the physiological model, suggesting the importance of three-dimensional heart simulation with realistic tissue structure in which inhibition of IKs augmented the TDR.

DISCUSSION

Various methods have been proposed for the accurate assessment of the TdP risk of drugs (7, 8, 16, 17, 22, 24). In particular, in silico studies are expected to facilitate drug development by saving on the time and cost inherent to animal experiments. However, most in silico studies examining the drug effect on multiple ion channels only evaluate surrogate markers including the relative inhibitory actions on the major ion currents dominating the repolarization phase of the myocardium (22), the hERG IC50 relative to ETPCunbound (16), or the action potential duration of the cell model of cardiac electrophysiology (7), rather than directly assessing the TdP occurrence. The use of whole heart experiments allows direct assessment of TdP risk but requires repeated measurement to compensate for biological variability, requiring considerable time and cost. To overcome these problems, researchers have attempted multiscale heart simulations that can directly assess the TdP risk based on cellular and molecular electrophysiology (8, 25, 26). To our knowledge, however, this is the first report of in silico TdP risk assessment based on a realistic heart model producing a realistic standard ECG.

Although we could successfully identify safe drugs from a limited data set, there are multiple problems to be solved for accurate quantitative risk assessment. First, in this study, we only used the conduction block model based on the steady-state inhibitory effect of drugs, and ignored their state- or voltage-dependent binding and unbinding. Indeed, as discussed by Mirams et al. (7), the time scale of binding and unbinding is much longer than the time scale of channel transition. The impact of this phenomenon should be examined in future studies, as well as the effect of changes of the detailed kinetic parameters in the gating processes. Second, although this simulation model is based on the detailed mechanisms of cardiac electrophysiology, it cannot reproduce the effect on channels not evaluated experimentally. To address this problem of unknown drug effects, we simulated the effect of a hypothetical new drug by adding the inhibitory action of other channels to the pharmacological characteristics of verapamil. These studies showed that other channels may have only a minor effect on the arrhythmogenesis.

Although the four to six channels assayed in this study were required for screening purposes, our conclusions remain speculative given the small number of analyzed compounds. Thus, further studies are required, particularly when considering the growing diversity in new drug targets. Finally, we simulated only cases of fixed regular HR in this study. Because TdP is often precipitated by the irregular short-long-short ventricular cycle, we simulated such a sequence under the influence of cisapride, and found that TdP could be induced at a slightly lower drug concentration compared with the regular rhythm (fig. S6). Such a pacing protocol is also clinically important because it corresponds to the provocation test in electrophysiology laboratories. Nevertheless, comprehensive analyses of the effects of basic cycle length and pacing patterns needing a large amount of computation are required in future studies.

Although the incidence of TdP is extremely low after drug marketing, its occurrence is often precipitated by confounding factors including hypokalemia, liver dysfunction, female gender, preexisting heart diseases, and genetic polymorphism in potassium channels modifying functions or sensitivity to drugs (1, 27, 28). As an example, we simulated a case of a common polymorphism with slight alterations of current (reduced by 25% and increased by 25%), but with retention of the sensitivity to cisapride similar to the wild-type channel (28). This apparently silent change in channel function decreased the threshold value for TdP and thus increased arrhythmia propensity (fig. S4). Concomitant use of other drugs may also modify the arrhythmogenic risk. We tested the combination of amiodarone and clarithromycin assuming a synergistic (multiplicative) interaction between them, and found that the concomitant use of macrolide antibiotics induces TdP with this safe drug (fig. S5), as previously reported (29). With further improvement, the simulation power of our model will enable us to evaluate the effects of other factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro current assay

Ion currents were recorded in CHO or Chinese hamster lung (CHL) cells expressing either hERG (IKr), Nav1.5 (INa), Cav1.2/b2/a2-d (ICa), KCNQ1 + KCNE1 (IKs), Kir2.1 (IK1), or Kv4.3 + KChIP2 (Ito) channels using the Sophion QPatch HTX system and software (QPatch Assay Software 5.0, Biolin Scientific) using the following cell lines, assay buffers, and voltage protocols.

Cell lines

hERG (KCNH2 gene) channels were stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells. Nav1.5 (SCN5A gene, hNav1.5 channel) channels were stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells. Cav1.2 (CACNA1C/CACNB2/CACNA2D1 genes) channels were stably expressed in CHO cells. IKs (KCNQ1/KCNE1 genes) channels were stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells. IK1 (KCNJ2 gene) channels were stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells. Ito (KCND3/KChIP2 genes) channels were stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells. hERG, Nav1.5, IKs, and IK1 cell lines were established in Eisai. The Ito cell line was established by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University. The Cav1.2 cell line was purchased from ChanTest Corporation.

Assay buffers

For IKr, IK1, and Ito: extracellular solution and internal solution containing 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and 120 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KOH/EGTA, 4 mM Na2-ATP (adenosine triphosphate), 10 mM Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. For INa: extracellular solution and internal solution containing 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and 135 mM CsF, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. For ICa: extracellular solution and internal solution containing 137 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and 80 mM l-aspartic acid, 130 mM CsOH, 5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM Na2-ATP, 0.1 mM (tris)guanosine triphosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with l-aspartic acid. For IKs: extracellular solution and internal solution containing 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and 110 mM K-gluconate, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 4 mM Na2-ATP, 10 mM Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH.

Voltage protocols

IKr was induced by the application of depolarizing step pulses to +20 mV with 2000-ms duration, followed by step pulses to −50 mV with 2000-ms duration from a holding potential of −80 mV every 15 s. The inhibition ratio of the tail current at −50 mV was calculated as hERG inhibition. INa was induced by the application of 30 repetitive depolarizing pulses to −10 mV with 50-ms duration from a holding potential of −90 mV at 2 Hz. The inhibition ratio of peak inward current at the 30th pulse was calculated as INa inhibition. For ranolazine, the inhibitory effect on the late component of INa was also included using the previously reported parameters (30, 31). ICa was induced by the application of depolarizing step pulses to 0 mV with 150-ms duration from a holding potential of −40 mV every 5 s. The inhibition ratio of peak inward current was calculated as ICa inhibition, except for ranolazine in which the late component was evaluated (30). IKs was induced by the application of depolarizing step pulses to +40 mV with 2000-ms duration, followed by step pulses to −50 mV with 500-ms duration from a holding potential of −80 mV every 5 s. The inhibition ratio of tail current at −50 mV was calculated as IKs inhibition. IK1 was induced by the application of hyperpolarizing step pulses to −120 mV with 500-ms duration, followed by ramp pulses to +40 mV with 2500-ms duration from a holding potential of 0 mV every 15 s. The inhibition ratio of current amplitude at steady phase at −120 mV was calculated as IK1 inhibition. Ito was induced by the application of depolarized potential to +20 mV with 500-ms duration from a holding potential of −80 mV every 15 s. The inhibition ratio of current amplitude at 100 ms of depolarizing step pulses was calculated as Ito inhibition.

Drug concentrations were varied up to 200 times of ETPCunbound. Drug effects were analyzed for each channel by normalizing the current by its maximum value obtained in the absence of the drug and fit to the Hill equation, where x and h represent the drug concentration and Hill constant, respectively.

Nonlinear least square fits were solved by GraphPad Prism version 6.02 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Electrophysiology simulation and ECG analysis

Simulation of drug effects on human cardiac electrophysiology was performed using the healthy adult model of the UT-Heart (10, 14). Cell models specific for the ventricular myocyte (32) and conduction system (33) were implemented to each FEM node to reproduce the physiological distribution of different cell species (endocardial, M, and epicardial cells) in the ventricular wall (10, 23). The propagation of excitation was solved with the bidomain formulation (34, 35) using the parallel multilevel technique we previously developed (14). To achieve the physiological speed of propagation, a minor modification of the activation gate parameters was necessary in the ventricular cell model (32). To save computational time, only the ventricles were used, and the stimulus was applied to the root of the conduction system at 1.2, 1, and 2/3 Hz to mimic the regular sinus rhythm. In most cases, we calculated five beats, although the duration was extended when necessary. From the body surface potential data, we obtained the 12-lead ECG according to the standard lead locations and measured the QT intervals in limb lead II. Computation was performed with a parallel computer system [Intel Xeon E5-2670 (2.6 GHz), 254 cores] and the computational time was 3 hours for a single beat. All the program codes were written in-house.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through its Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST Program). Author contributions: J.O. wrote program codes, carried out computations, drafted the manuscript, and participated in the design of the study. T.Y. and J.K. carried out experiments and participated in the design of the study. T.W. wrote program codes and carried out computations. T.F. and K.S. conceived the study and participated in its design. S.S. participated in the study design and helped to draft the manuscript. T.H. helped to write the program codes and participated in the design and coordination of the study. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: The following cell lines were obtained under a material transfer agreement: Ito (CHO-K1) cell line stably overexpressing the KCND3/KChIP2 genes (J.K.); hERG cell line (CHO-K1) stably expressing the KCNH2 gene, Nav1.5 cell line (CHL) stably expressing the SCN5A gene, Iks cell line (CHO-K1) stably expressing the KCNQ1/KCNE1 genes, and Iks cell line (CHO-K1) stably expressing the KCNJ2 gene (K.S. and T.Y.).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/4/e1400142/DC1

Fig. S1. Simulated 12-lead ECG.

Fig. S2. Drug effects on two-lead ECG.

Fig. S3. Effect of hypothetical multichannel blockers on ECG.

Fig. S4. Effect of cisapride for a subject carrying a common polymorphism of hERG channel.

Fig. S5. Effect of concomitant use of clarithromycin on the arrhythmogenicity of amiodarone.

Fig. S6. Effect of irregular heartbeats.

Table S1. Inhibitory actions of 12 drugs on six ion channels.

Table. S2. Abbreviations.

Movie S1. Simulation of regular heartbeat.

Movie S2. Simulation of drug-induced arrhythmia.

Reference (36)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Yap Y. G., Camm A. J., Drug induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Heart 89, 1363–1372 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah R. R., Drugs, QTc interval prolongation and final ICH E14 guideline: An important milestone with challenges ahead. Drug Saf. 28, 1009–1028 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamburg M. A., Advancing regulatory science. Science 331, 987 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi K. R., Revolution dawning in cardiotoxicity testing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 565–567 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sager P. T., Gintant G., Turner J. R., Pettit S., Stockbridge N., Rechanneling the cardiac proarrhythmia safety paradigm: A meeting report from the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Am. Heart J. 167, 292–300 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki S., Murakami S., Tsujimae K., Findlay I., Kurachi Y., In silico risk assessment for drug-induction of cardiac arrhythmia. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 98, 52–60 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirams G. R., Cui Y., Sher A., Fink M., Cooper J., Heath B. M., McMahon N. C., Gavaghan D. J., Noble D., Simulation of multiple ion channel block provides improved early prediction of compounds’ clinical torsadogenic risk. Cardiovasc. Res. 91, 53–61 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie K. A., Luscombe C., Williams G., Munoz-Muriedas J., Gavaghan D. J., Cui Y., Mirams G. R., Evaluation of an in silico cardiac safety assay: Using ion channel screening data to predict QT interval changes in the rabbit ventricular wedge. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 68, 88–96 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe H., Sugiura S., Kafuku H., Hisada T., Multiphysics simulation of left ventricular filling dynamics using fluid-structure interaction finite element method. Biophys. J. 87, 2074–2085 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada J., Washio T., Maehara A., Momomura S., Sugiura S., Hisada T., Transmural and apicobasal gradients in repolarization contribute to T-wave genesis in human surface ECG. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301, H200–H208 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washio T., Okada J., Sugiura S., Hisada T., Approximation for cooperative interactions of a spatially-detailed cardiac sarcomere model. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 5, 113–126 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugiura S., Washio T., Hatano A., Okada J., Watanabe H., Hisada T., Multi-scale simulations of cardiac electrophysiology and mechanics using the University of Tokyo heart simulator. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 110, 380–389 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washio T., Okada J., Takahashi A., Yoneda K., Kadooka Y., Sugiura S., Hisada T., Multiscale heart simulation with cooperative stochastic cross-bridge dynamics and cellular structures. SIAM J. Multiscale Model Simul. 11, 965–999 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Washio T., Okada J., Hisada T., A parallel multilevel technique for solving the bidomain equation on a human heart with Purkinje fibers and a torso model. SIAM Rev. 52, 717–743 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada J., Sasaki T., Washio T., Yamashita H., Kariya T., Imai Y., Nakagawa M., Kadooka Y., Nagai R., Hisada T., Sugiura S., Patient specific simulation of body surface ECG using the finite element method. PACE 36, 309–321 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfern W. S., Carlsson L., Davis A. S., Lynch W. G., MacKenzie I., Palethorpe S., Siegl P. K., Strang I., Sullivan A. T., Wallis R., Camm A. J., Hammond T. G., Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: Evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc. Res. 58, 32–45 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence C. L., Bridgland-Taylor M. H., Pollard C. E., Hammond T. G., Valentin J.-P., A rabbit Langendorff heart proarrhythmia model: Predictive value for clinical identification of Torsades de Pointes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 149, 845–860 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchanan L., Kabell G., Brunden M. N., Gibson J. K., Comparative assessment of ibutilide, d-sotalol, clofilium, E-4031, and UK-68,798 in a rabbit model of proarrhythmia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 220, 540–549 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sager P. T., Key clinical considerations for demonstrating the utility of preclinical models to predict clinical drug-induced torsades de pointes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 1544–1549 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darpo B., Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 3, K70–K80 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 21.A. T. M.-A. Investigators , Effect of prophylactic amiodarone on mortality after acute myocardial infarction and in congestive heart failure: Meta-analysis of individual data from 6500 patients in randomised trials. Lancet 350, 1417–1424 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer J., Obejero-Paz C. A., Myatt G., Kuryshev Y. A., Bruening-Wright A., Verducci J. S., Brown A. M., MICE models: Superior to the HERG model in predicting Torsade de Pointes. Sci. Rep. 3, 2100 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antzelevitch C., Cellular basis for the repolarization waves of the ECG. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1080, 268–281 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bottino D., Penland R. C., Stamps A., Traebert M., Dumotier B., Georgiva A., Helmlinger G., Lett G. S., Preclinical cardiac safety assessment of pharmacological compounds using an integrated system-based computer model of the heart. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 90, 413–443 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirams G. R., Davies M. R., Cui Y., Kohl P., Noble D., Application of cardiac electrophysiology simulations to pro-arrhythmic safety testing. Br. J. Pharmacol. 167, 932–945 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zemzemi N., Bernabeu M. O., Saiz J., Cooper J., Pathmanathan P., Mirams G. R., Pitt-Francis J., Rodriguez B., Computational assessment of drug-induced effects on the electrocardiogram: From ion channel to body surface potentials. Br. J. Pharmacol. 168, 718–733 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He F. Z., McLeod H. L., Zhang W., Current pharmacogenomic studies on hERG potassium channels. Trends Mol. Med. 19, 227–238 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anson B. D., Ackerman M. J., Tester D. J., Will M. L., Delisle B. P., Anderson C. L., January C. T., Molecular and functional characterization of common polymorphisms in HERG (KCNH2) potassium channels. Am. J. Physiol. 286, H2434–H2441 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Justo D., Zeltser D., Torsades de pointes induced by antibiotics. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 17, 254–259 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antzelevitch C., Belardinelli L., Zygmunt A. C., Burashnikov A., Di Diego J. M., Fish J. M., Cordeiro J. M., Thomas G., Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation 110, 904–910 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chevalier M., Amuzescu B., Gawali V., Todt H., Knott T., Scheel O., Abriel H., Late cardiac sodium current can be assessed using automated patch-clamp. F1000Res. 3, 245 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Hara T., Virag L., Varro A., Rudy Y., Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: Model formulation and experimental validation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002061 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart P., O. V. Aslanidi, D. Noble, P. J. Noble, M. R. Boyett, H. Zhang, Mathematical models of the electrical action potential of Purkinje fibre cells. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 367, 2225–2255 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henriquez C. S., Simulating the electrical behavior of cardiac tissue using the bidomain model. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 21, 1–77 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth B., How the anisotropy of the intracellular and extracellular conductivities influences stimulation of cardiac muscle. J. Math. Biol. 30, 633–646 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gluais P., Bastide M., Grandmougin D., Fayad G., Adamantidis M., Clarithromycin reduces Isus and Ito currents in human atrial myocytes with minor repercussions on action potential duration. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 17, 691–701 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/4/e1400142/DC1

Fig. S1. Simulated 12-lead ECG.

Fig. S2. Drug effects on two-lead ECG.

Fig. S3. Effect of hypothetical multichannel blockers on ECG.

Fig. S4. Effect of cisapride for a subject carrying a common polymorphism of hERG channel.

Fig. S5. Effect of concomitant use of clarithromycin on the arrhythmogenicity of amiodarone.

Fig. S6. Effect of irregular heartbeats.

Table S1. Inhibitory actions of 12 drugs on six ion channels.

Table. S2. Abbreviations.

Movie S1. Simulation of regular heartbeat.

Movie S2. Simulation of drug-induced arrhythmia.

Reference (36)