Significance

Loss of dystrophin in Duchenne muscular dystrophy results in a secondary disruption of muscle nitric oxide (NO) signaling thought to contribute to exaggerated muscle fatigue and cardiac dysfunction in this disease. How muscle NO synthesis is regulated, and how dystrophin and the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex participate, are poorly understood. Using isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes as a model of striated muscle, we provide evidence for a mechanism in which the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex functions as a mechanosensor to activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which then phosphorylates NOS to increase NO production in response to direct mechanical stimulation. This paper also provides proof-of-concept evidence for acute pharmacologic AMPK activation as a therapy to restore NO synthesis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Keywords: cardiomyocyte, stretch, dystrophin, nNOS, AMPK

Abstract

Patients deficient in dystrophin, a protein that links the cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix via the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC), exhibit muscular dystrophy, cardiomyopathy, and impaired muscle nitric oxide (NO) production. We used live-cell NO imaging and in vitro cyclic stretch of isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes as a model system to investigate if and how the DGC directly regulates the mechanical activation of muscle NO signaling. Acute activation of NO synthesis by mechanical stretch was impaired in dystrophin-deficient mdx cardiomyocytes, accompanied by loss of stretch-induced neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) S1412 phosphorylation. Intriguingly, stretch induced the acute activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in normal cardiomyocytes but not in mdx cardiomyocytes, and specific inhibition of AMPK was sufficient to attenuate mechanoactivation of NO production. Therefore, we tested whether direct pharmacologic activation of AMPK could bypass defective mechanical signaling to restore nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. Indeed, activation of AMPK with 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside or salicylate increased nNOS S1412 phosphorylation and was sufficient to enhance NO production in mdx cardiomyocytes. We conclude that the DGC promotes the mechanical activation of cardiac nNOS by acting as a mechanosensor to regulate AMPK activity, and that pharmacologic AMPK activation may be a suitable therapeutic strategy for restoring nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient hearts and muscle.

The muscular dystrophies are a group of muscle wasting disorders characterized by progressive weakening and degeneration of striated muscle. The most common form is Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked disorder caused by genetic disruption of dystrophin (1) that affects 1 in 3,500–5,000 males (2, 3). DMD and several other types of muscular dystrophy result from disruption of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC), a structure that spans the sarcolemma and forms a mechanical linkage between the cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix via the association of dystrophin with subsarcolemmal γ-actin and the binding of α-dystroglycan to laminin (4). The generally accepted role for this complex is to act as a molecular shock absorber and stabilize the plasma membrane during muscle contraction. Disruption of the DGC’s linkage between the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix, such as occurs in DMD (1, 5–7) or with the disruption of α-dystroglycan–laminin binding in glycosylation-deficient muscular dystrophies (8, 9), leads to destabilization of the plasma membrane, rendering skeletal muscle fibers and cardiomyocytes susceptible to stretch- or contraction-induced injury and cell death (10–14).

In addition to this structural role, a signaling function for the DGC has been proposed based on its association with several signaling proteins including Grb2-Sos1 (15), MEK and ERK (16), heterotrimeric G protein subunits (17, 18), archvillin (19), and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) (20–22). The current dogma is that the DGC serves as a passive scaffold for these molecules, anchoring them near sites of action or important partners, with genetic disruption of the DGC leading to mislocalization, destabilization, or ineffective recruitment of these molecules to the complex (23).

In healthy skeletal muscle, nNOS binds to the DGC via direct physical interactions with dystrophin and α-1 syntrophin (20, 22, 24) and is thus anchored near the sarcolemma. During muscle contraction, nitric oxide (NO) produced from nNOS is thought to signal in a paracrine fashion to the vascular smooth muscle of arterioles that supply the skeletal muscle with blood, thereby locally counteracting vasoconstriction induced by increased sympathetic tone during exercise (25, 26). In DMD, genetic loss of dystrophin results in secondary mislocalization of nNOS from the skeletal muscle sarcolemma (20, 21), and impaired muscle NO production is observed. Disrupted muscle NO signaling impairs muscle blood flow regulation in dystrophin-deficient mice (27) and results in markedly exaggerated fatigue after exercise (28). Severe muscle fatigue is also a prominent feature of human DMD, and its improvement is considered an important clinical outcome for therapies, such that the 6-min walk test is an important endpoint for clinical trials in DMD (29). Despite growing appreciation of the physiological implications of disrupted muscle NO production, it remains unclear whether impaired nNOS activation in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle is a consequence of disrupted scaffolding of nNOS to the DGC, or whether the DGC acts as a mechanosensor in a mechanosignaling pathway that regulates nNOS activity. Furthermore, mechanical stimulation enhances nNOS and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity in cardiac muscle (30, 31), but whether such mechanosensitive cardiac NOS signaling occurs via one of these two possible mechanisms or depends on dystrophin is unknown.

Two reports have suggested that dystrophin-deficient hearts (32) and cardiomyocytes (33) exhibit impaired nNOS activity. Despite this apparent similarity of the effect of dystrophin deficiency on cardiac and skeletal muscle NOS signaling, another recent study has demonstrated that in contrast to skeletal muscle, nNOS is not physically associated with the DGC in cardiac muscle (34). These interesting observations suggest that dystrophin and the DGC’s impact on NO signaling might not result from a purely scaffolding function of the DGC for nNOS in striated muscle. Therefore, we hypothesized that dystrophin and the DGC act as a mechanosensor to couple the muscle cell’s mechanical activity to a biochemical signaling pathway leading to NO production, independent of a direct physical interaction between NOS and the DGC.

We used cardiomyocytes as a model for striated muscle, and performed in vitro mechanical stretching to investigate the direct involvement of dystrophin in mechanically activated muscle NO signaling and the potential role of the DGC as a mechanosensor. Here we report that acute mechanical activation of NO production is impaired in dystrophin-deficient mouse cardiomyocytes, and identify disrupted mechano-AMPK-nNOS signaling as a key component of altered NO production in these cells. These findings suggest that dystrophin and the DGC play more than a passive structural role in striated muscle, and rather may be active participants in mechanotransduction. Finally, we demonstrate that acute pharmacologic activation of AMPK is sufficient to restore nNOS activity and NO production in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes, and propose that this may be a suitable strategy for bypassing disrupted mechanical signaling and restoring NO production in dystrophin-deficient striated muscle.

Results

Mechanical Stretch Activates NO Production in Adult Mouse Cardiomyocytes.

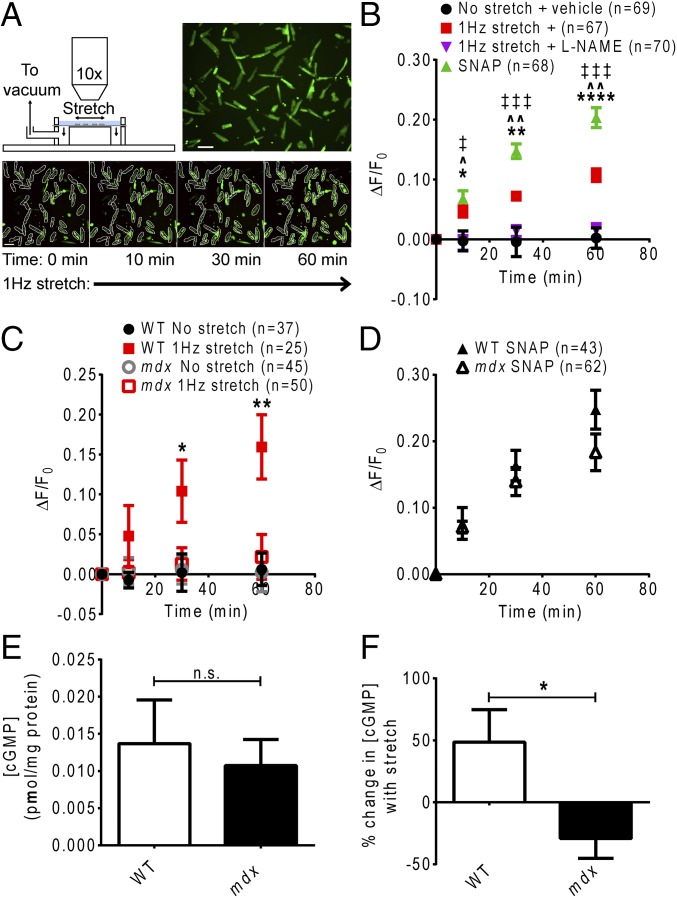

To investigate mechanically activated muscle NO signaling, we established an assay using the NO-sensitive dye 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM-DA) to monitor cellular NO production during in vitro cyclic stretch of isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes. On entering cells, DAF-FM-DA is cleaved to form 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein (DAF-FM), which increases in fluorescence on irreversible binding with NO oxide (35), and thus can be used to assess cumulative cellular NO production over time. Cyclic 1-Hz stretch of wild-type (WT) cardiomyocytes elicited a significant increase in DAF-FM dye fluorescence over the course of 1 h compared with nonstretched cells (Fig. 1 A and B). This stretch-induced increase in DAF-FM fluorescence was abolished by incubation of the cardiomyocytes with the general NO synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine-methyl-ester (l-NAME), verifying that the stretch-induced increase in dye fluorescence was due to increased NO production (Fig. 1B). DAF-FM fluorescence was also increased by treating cells with the exogenous NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Stretch-dependent NO signaling is impaired in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. (A) Experimental setup. Adult mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with DAF-FM are visualized under 10x magnification using an epifluorescence microscope throughout 1 h of 1-Hz stretch. (Scale bar: 100 µm.) DAF-FM fluorescence in each rod-shaped, nonfibrillatory cardiomyocyte is quantified throughout the protocol. (B) Validation of NO imaging assay. Stretch of WT cardiomyocytes induces a significant increase in DAF-FM fluorescence (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, stretch vs. no stretch + vehicle). Incubation with the NOS inhibitor L-NAME abolishes the stretch-induced increase in DAF-FM fluorescence (^P < 0.001, ^^P < 0.0001, stretch + vehicle vs. L-NAME). Treatment with the NO donor SNAP yields a significant increase in DAF-FM fluorescence (‡P < 0.01, ‡‡‡P < 0.0001, SNAP vs. no stretch + vehicle). (C) The increase in DAF-FM fluorescence during stretch is significantly lower in mdx cardiomyocytes compared with WT cardiomyocytes (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, WT vs. mdx stretch). (D) Treatment with SNAP after stretch yields similar increases in DAF-FM fluorescence in WT and mdx cardiomyocytes. (E) There is no significant difference in cGMP concentration between WT and mdx cardiomyocytes before stretch (n = 8 mice). (F) The change in cGMP concentration downstream of NO in response to stretch is significantly altered in mdx cardiomyocytes vs. WT cardiomyocytes (n = 8 mice) (*P < 0.05).

Stretch-Dependent NO Signaling Is Disrupted in Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyocytes.

We then used this assay to test whether dystrophin is required for mechanically activated NO signaling in cardiac muscle. Under resting conditions, we detected no difference in changes in DAF-FM dye fluorescence between WT and dystrophin-deficient mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1C); however, the increase in DAF-FM dye fluorescence during stretch was significantly attenuated in mdx cardiomyocytes compared with WT cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1C), suggesting that dystrophin is required for appropriate mechanical activation of NO production in cardiac muscle. Treatment with SNAP after the stretch period produced a significant increase in DAF-FM fluorescence in both WT and mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1D). This finding verifies that mdx cardiomyocytes did effectively retain the dye, and that the diminished increase in dye fluorescence during stretch of these cells was indeed attributable to impaired NO production, rather than an artifact of the dye leaking out of the excessively permeable or damaged plasma membranes characteristic of dystrophic cardiomyocytes (14, 36). Measurement of cellular cGMP content downstream of NO production revealed no differences between WT and mdx cardiomyocytes at rest (Fig. 1E). One hour of 1-Hz stretch increased cGMP content in WT cardiomyocytes, but this effect was abrogated in mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1F). These data further support the idea that the loss of dystrophin disrupts mechanically activated cardiac NO production and may have physiologically relevant consequences on downstream signaling.

Stretch-Induced nNOS Phosphorylation Is Impaired in Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyocytes.

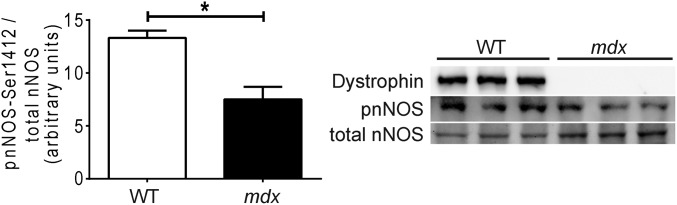

This defect in mechanically activated NO signaling prompted us to investigate the mechanism coupling dystrophin to cardiac NOS activity. Given that mRNA and protein content of the constitutively expressed NO synthases, nNOS and eNOS, is not reduced in mdx hearts (33), we hypothesized that impaired mechano-NO production in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes was related to misregulation of posttranslational modification required for NOS activity. The enzymatic activity of both nNOS and eNOS is under multiple levels of regulatory control that includes phosphorylation of several stimulatory or inhibitory residues (37, 38). Biochemical analysis revealed a significantly reduced ratio of serine 1412-phosphorylated to total nNOS in mdx heart lysates compared with WT heart lysates (Fig. 2). Interestingly, phosphorylation at this site increases nNOS activity (39).

Fig. 2.

Stimulatory nNOS phosphorylation is impaired in dystrophin-deficient hearts in vivo. The ratio of phospho-Ser1412-nNOS to total nNOS is significantly reduced in mdx hearts vs. WT hearts (n = 3 mice) (*P < 0.05).

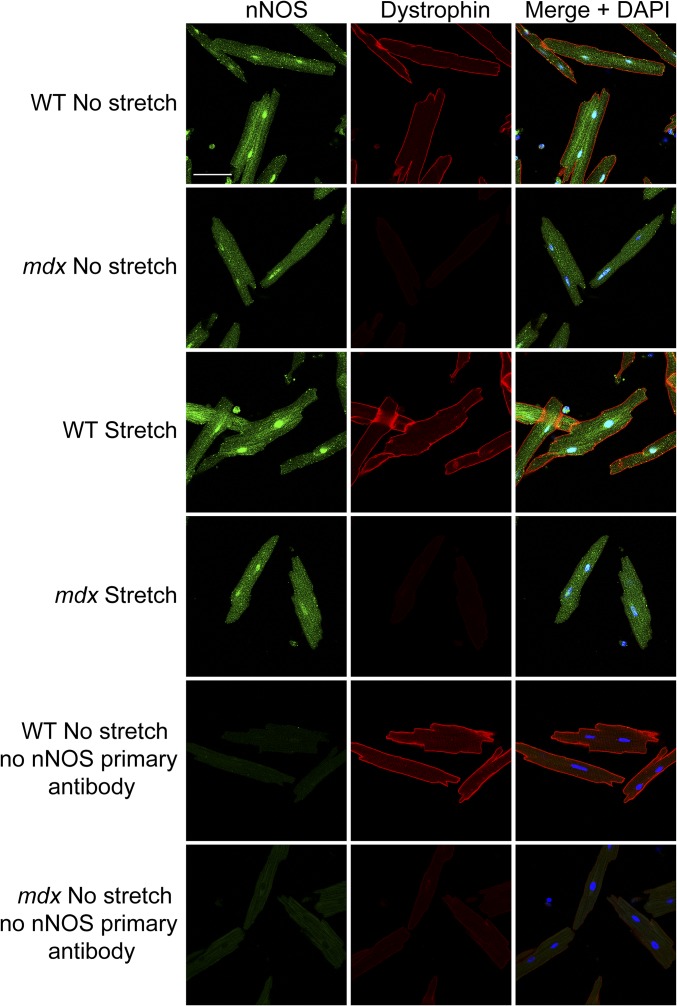

To investigate whether decreased nNOS phosphorylation in dystrophin-deficient hearts in vivo was due to disrupted mechanical signaling, we compared the impact of stretch on the nNOS-serine 1412 phosphorylation state in WT and mdx cardiomyocytes in vitro. Phosphorylation of this residue increased significantly over basal levels within 10 min of 1-Hz stretch in WT cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3A). Incubation of WT cardiomyocytes with the nNOS-specific inhibitor vinyl-l-NIO attenuated the stretch-induced increase in NO production (Fig. 3B), verifying that increased nNOS-serine 1412 phosphorylation during stretch was indeed associated with increased nNOS activity. Intriguingly, stretch failed to elicit an increase in nNOS-serine 1412 phosphorylation in mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence labeling revealed that nNOS was localized in the cytoplasm, in a striated pattern, and in the nucleus and was not specifically enriched at the sarcolemma of WT or mdx cardiomyocytes at rest (Fig. S1), in agreement with previous reports (33, 34). Moreover, stretch did not lead to membrane recruitment of nNOS or otherwise discernibly alter nNOS localization in either WT or mdx cells (Fig. S1). Collectively, these results suggest that the loss of dystrophin impairs the mechanical activation of cardiac nNOS not by disrupting a physical interaction between nNOS and the DGC, but rather by disrupting the mechanical signaling that regulates nNOS phosphorylation state and activity.

Fig. 3.

Stretch-induced nNOS and AMPK activation are impaired in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. (A) Acute stretch of WT cardiomyocytes elicits increased phosphorylation of nNOS at the stimulatory residue serine 1412, increased activating phosphorylation of AMPKα at threonine 172, and increased phosphorylation of ACC at serine 79 (*P < 0.05 vs. WT control). These effects are attenuated in mdx cardiomyocytes (#P < 0.05 vs. WT stretch) (n = 6 mice). (B) The increase in DAF-FM fluorescence during stretch of WT cardiomyocytes is significantly reduced in cells incubated with the nNOS-selective inhibitor vinyl-l-NIO (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, stretch + vehicle vs. vinyl-l-NIO). (C) The increase in DAF-FM fluorescence during stretch of WT cardiomyocytes is significantly reduced in cells incubated with the AMPK inhibitor Compound C (*P < 0.05, stretch + vehicle vs. Compound C).

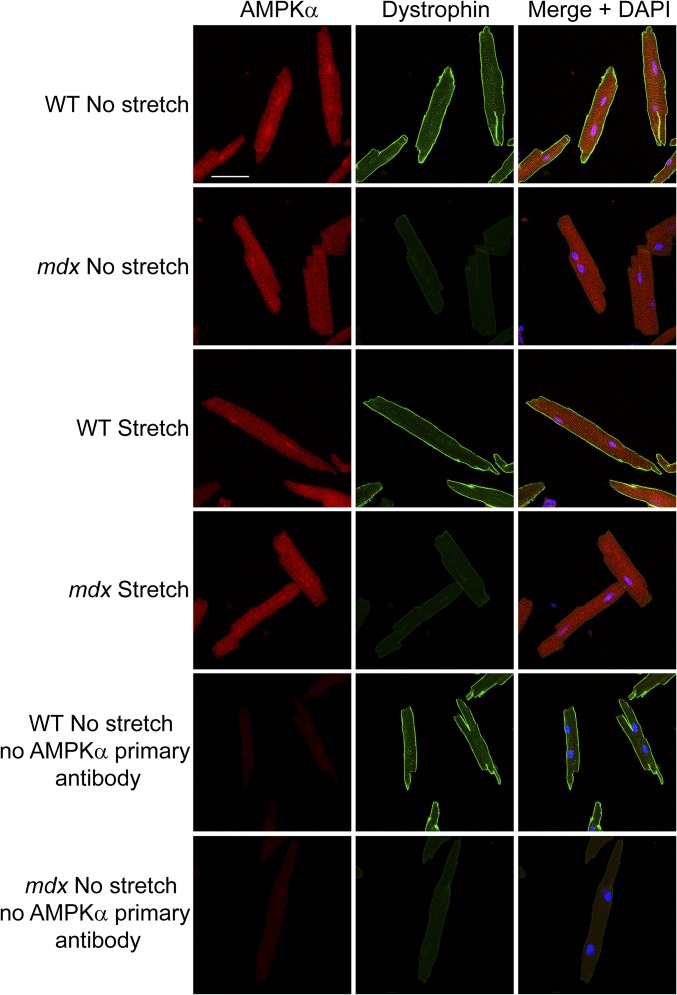

Fig. S1.

nNOS localization. WT and mdx cardiomyocytes exhibit cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of nNOS (green) at rest. nNOS is not specifically enriched at the sarcolemma and does not colocalize with dystrophin (red). Cyclic stretch (1-Hz) does not lead to a discernible change in nNOS localization in either WT or mdx cardiomyocytes. (Scale bar: 50 µm.)

Stretch-Induced AMPK Phosphorylation Is Impaired in Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyocytes.

We next sought to determine the mechanosensitive signaling pathway that couples dystrophin to stretch-induced activation of nNOS. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylates nNOS-serine 1412 in multiple cell types, including skeletal muscle (40–43), and can be activated by mechanical stimulation of cardiac muscle (44, 45). Therefore, we investigated the involvement of AMPK in dystrophin-dependent mechano-nNOS signaling in cardiomyocytes. Western blot analysis demonstrated that stretch of WT cardiomyocytes increased phosphorylation of the catalytic alpha subunit of AMPK at threonine 172 (Fig. 3A), a modification that reflects increased AMPK activity (46). Stretch of WT cardiomyocytes also increased phosphorylation of the classical AMPK substrate acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) at serine 79 (Fig. 3A), reinforcing the idea that stretch activates AMPK. Incubation with the AMPK inhibitor Compound C attenuated the stretch-induced increase in DAF-FM fluorescence in WT cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3C), confirming that AMPK activation contributes to mechanically induced NO production in these cells. Notably, a 1-Hz stretch of mdx cardiomyocytes failed to increase phosphorylation of AMPKα-threonine 172 and ACC-serine 79 (Fig. 3A), indicating that dystrophin is required for appropriate mechanical activation of AMPK.

The foregoing findings further imply that impaired mechanoactivation of AMPK contributes to impaired mechanoactivation of nNOS in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Similar to nNOS, AMPK displayed striated cytoplasmic and nuclear staining and was not associated with the sarcolemma in WT or mdx cardiomyocytes either at rest or after stretch (Fig. S2), raising the possibility that additional intermediate signaling factors couple the DGC to the regulation of AMPK.

Fig. S2.

AMPKα localization. WT and mdx cardiomyocytes exhibit cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of AMPKα (red) at rest. AMPKα is not specifically enriched at the sarcolemma and does not colocalize with dystrophin (green). Cyclic stretch (1-Hz) does not lead to a discernible change in AMPKα localization in either WT or mdx cardiomyocytes. (Scale bar: 50 µm.)

Pharmacologic AMPK Activation Restores nNOS Activity in Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyocytes.

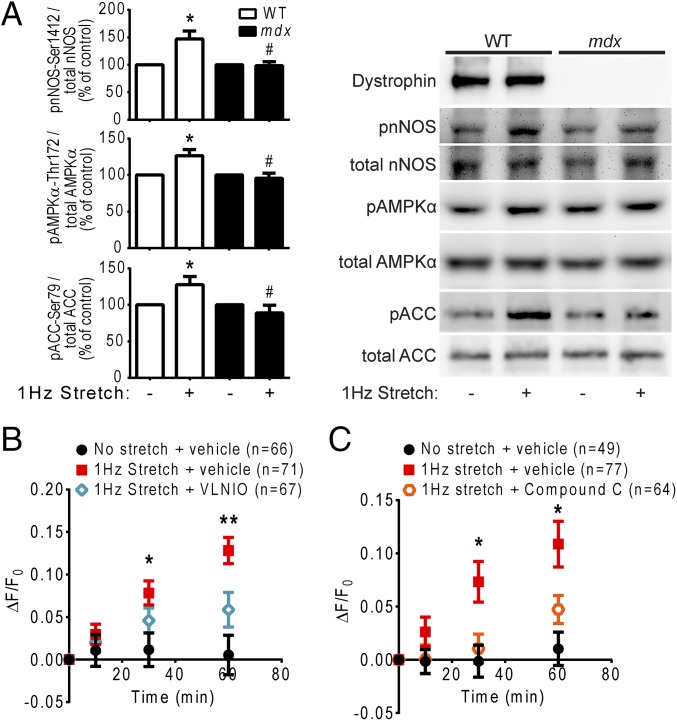

There is increasing interest in using AMPK activation as a therapeutic strategy to improve muscle pathology in DMD. Chronic activation of AMPK with administration of the AMP analog 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR) (47) in mdx mice has been shown to promote a slow oxidative muscle phenotype, increase utrophin expression, and enhance sarcolemmal stability in skeletal muscle (48), and to reduce ongoing muscle damage and increase skeletal muscle strength (49, 50). Whether any of these effects depends on increased NO production, and whether AMPK activation can enhance NO production in the dystrophic heart, are unclear. Therefore, we tested whether acute pharmacologic activation of AMPK is sufficient to restore nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. Indeed, treatment with AICAR or with the AMPK-activating drug salicylate (51) significantly increased DAF-FM dye fluorescence in mdx cardiomyocytes compared with vehicle controls and at levels similar to treated WT cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4 A and C). Inhibition of nNOS with vinyl-l-NIO attenuated AICAR- and salicylate-induced increases in DAF-FM fluorescence in mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4 B and D). Consistent with these data, acute 60-min treatment with AICAR or salicylate increased the activating phosphorylation of AMPKα-threonine 172 and increased stimulatory phosphorylation of nNOS-serine 1412 in both WT and mdx cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5 A and B). Taken together, these results indicate that AMPK stimulates NO production in cardiomyocytes, and that acute pharmacologic AMPK activation is sufficient to restore nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes.

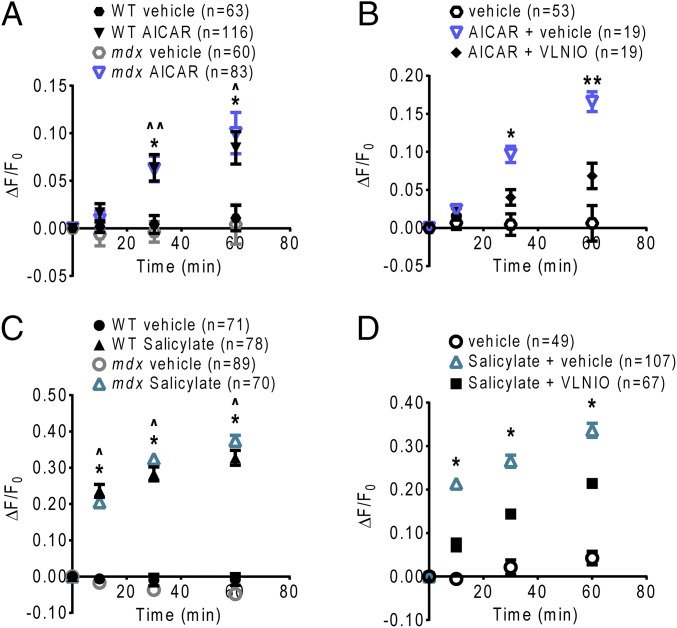

Fig. 4.

Pharmacologic AMPK activation increases nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. (A) Treatment with AICAR elicits a significant increase in DAF-FM fluorescence in both WT and mdx cardiomyocytes (*P < 0.01, WT AICAR vs. vehicle; ^P < 0.01, ^^P < 0.001, mdx AICAR vs. vehicle). (B) nNOS inhibition with vinyl-l-NIO attenuates the increase in DAF-FM fluorescence induced by AICAR in mdx cardiomyocytes (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.0001, AICAR + vehicle vs. AICAR + vinyl-l-NIO). (C) Treatment with salicylate elicits a significant increase in DAF-FM fluorescence in both WT and mdx cardiomyocytes (*P < 0.0001, WT salicylate vs. vehicle; ^P < 0.0001, mdx salicylate vs. vehicle). (D) nNOS inhibition with vinyl-l-NIO attenuates the increase in DAF-FM fluorescence induced by salicylate in mdx cardiomyocytes (*P < 0.0001, salicylate + vehicle vs. salicylate + vinyl-l-NIO).

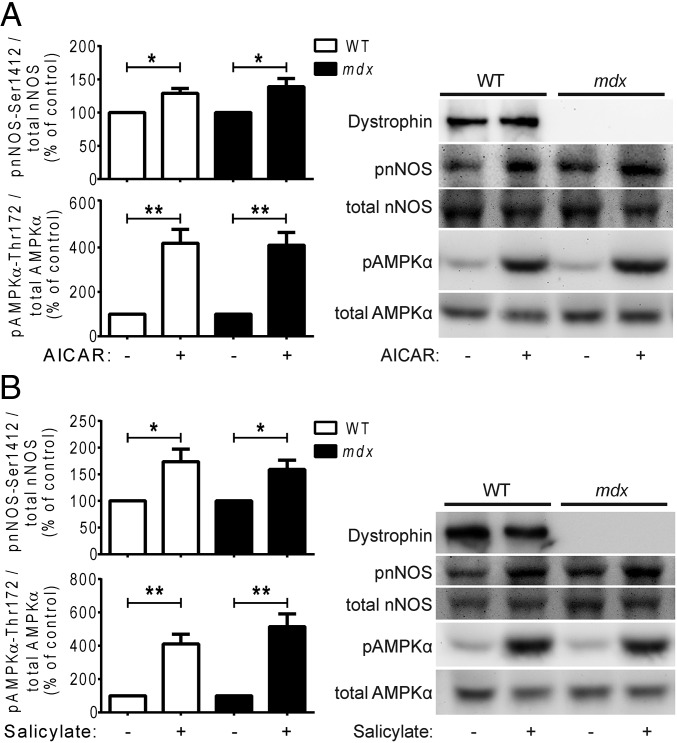

Fig. 5.

Pharmacologic AMPK activation increases stimulatory nNOS phosphorylation in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes. (A) Acute treatment of WT and mdx cardiomyocytes with the AMPK activator AICAR increases activating phosphorylation of AMPKα at threonine 172 and increases stimulatory phosphorylation of nNOS at serine 1412 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control) (n = 6 mice). (B) Acute treatment of WT and mdx cardiomyocytes with the AMPK activator salicylate increases activating phosphorylation of AMPKα at threonine 172 and increases stimulatory phosphorylation of nNOS at serine 1412 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control) (n = 7 mice).

Discussion

Thirty years of research into the molecular mechanisms of the muscular dystrophies supports an important structural role for the DGC in stabilizing the plasma membrane of striated muscle cells. Increasing evidence suggests that the integrity of the DGC has important consequences for cell signaling as well (15–22); however, the passive effects of the DGC to scaffold signaling proteins (23) have not yet been distinguished from the potential for the DGC to participate actively as a mechanosensor to regulate cellular signaling. This question is particularly pertinent to elucidating the mechanisms of muscle NO signaling, considering that whether impaired nNOS function in DMD is a direct structural consequence of disrupted localization of nNOS to the sarcolemma by the DGC, or whether disruption of the DGC leads to altered posttranslational regulation of nNOS activity, remains unclear.

Here we used adult cardiomyocytes as a model of differentiated striated muscle to address the hypothesis that the DGC functions directly as a mechanosensor to regulate NO signaling in muscle. Our observation of impaired mechanically stimulated nNOS-serine 1412 phosphorylation in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes provides direct mechanistic evidence of why nNOS activity is impaired in dystrophin-deficient cardiac muscle. It is also consistent with an earlier report of reduced nNOS activity in total lysates from mdx mouse hearts (32), given that the heart is stimulated mechanically by contraction in vivo. Moreover, the fact that such dystrophin-dependent mechanical nNOS signaling is independent of a physical interaction between nNOS and the cardiac DGC suggests that the DGC is not merely a passive scaffold for nNOS, but rather is an active regulator of a signaling pathway that controls nNOS activity in cardiac muscle, and possibly in skeletal muscle as well. A model in which dystrophin loss results in loss of AMPK-dependent regulation of nNOS also would help explain why deletion of nNOS does not dramatically worsen muscle pathology in mdx mice (52, 53), because the activation of any nNOS expressed in dystrophin-deficient muscle would already be impaired.

AMPK has been considered a potential candidate kinase for regulating nNOS phosphorylation. Our finding that mechanical activation of AMPK contributed to NO production in WT cardiomyocytes and was impaired in mdx cardiomyocytes suggests that impaired stretch-induced activation of nNOS with loss of dystrophin is due to impaired mechanical activation of AMPK. The identification of a dystrophin-AMPK-nNOS mechanical signaling axis in adult striated muscle is particularly interesting given the finding that the activation of AMPK by stretch of alveolar epithelial cells depends on dystroglycan (54), a core component of the muscle DGC.

Taken together, these observations indicate that DGC-AMPK signaling may be an important component of mechanosensing across multiple cell and tissue types. AMPK expressed in cardiac muscle did not appear to colocalize with dystrophin at the sarcolemma. Thus, in future studies it will be important to determine the mechanism by which the DGC regulates AMPK activity, such as through regulation of the putative AMPK kinases liver kinase B1 or calcium-calmodulin–activated protein kinase kinase-β, or perhaps by preventing the excessive production of reactive oxygen species during stretch (55).

AMPK has been identified as an important therapeutic target in various disorders, including diabetes and aging, and plays an important role in long-term adaptation of muscle to exercise. We demonstrate that acute, direct pharmacologic AMPK activation by either AICAR or salicylate mechanistically targets altered nNOS regulation and is sufficient to restore nNOS activity in dystrophin-deficient cardiac muscle. Several other strategies to boost NO and downstream cGMP signaling in the dystrophin-deficient heart have been tested, including transgenic myocardial expression of an nNOS transgene (56) and chronic administration of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (57). Such studies have yielded mixed results in animal models, with modest improvements in cardiac function and pathology. Furthermore, human trials have offered little evidence of a beneficial cardiac effect of sildenafil treatment in adults with DMD or Becker muscular dystrophy (58, 59). In light of our findings, it is possible that the shortcomings of these previous studies reflect the existence of other functional targets of muscle-derived NO, or additional targets of altered AMPK regulation, that contribute to dysfunction in dystrophic muscle (43, 60, 61). This possibility warrants further investigation into whether acute AMPK activation can yield therapeutic benefit to dystrophic patients through the restoration of heart or skeletal muscle NO signaling.

Taken together, our data support a model in which dystrophin or an intact DGC is required as a mechanosensor for the appropriate activation of AMPK by mechanical stimulation in cardiac muscle. Dystrophin-dependent mechanical activation of AMPK then triggers stimulatory phosphorylation of nNOS-serine 1412, leading to increased cellular NO production. Loss of dystrophin expression in DMD uncouples mechanical stimulation from the activation of AMPK, ultimately leading to failure to appropriately activate nNOS and resulting in impaired mechano-NO production. Further study is needed to clarify the contributions of disrupted mechano-AMPK-NO signaling to cardiac dysfunction in DMD and to determine whether disrupted mechano-AMPK signaling similarly contributes to the disease phenotype, including nNOS impairment, in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Importantly, AMPK signaling may provide a new pharmacologic target for restoring defective NO regulation in striated muscle and for improving cardiac and skeletal muscle blood flow in muscular dystrophy and other diseases in which muscle blood flow is compromised.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Control WT C57 and dystrophin-deficient mdx mice were used at 8–25 wk, before the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy (57). All animals were housed at the University of Michigan’s Unit for Laboratory Medicine, and all procedures were approved by the University of Michigan’s Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Cardiomyocyte Isolation and General Plating Conditions.

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from adult mouse hearts as described previously (62). After isolation, cardiomyocytes were resuspended in plating medium (Table S1) and plated for 2 h as described below.

Table S1.

Plating medium composition

| Reagent | Final concentration |

| MEM (Gibco 1157–032) | |

| FBS | 5% (vol/vol) |

| Penicillin G sodium salt | 100 U/mL |

| Glutamine | 2 mM |

| BSA | 0.2% |

| NaHCO3 | 4 mM |

| Hepes | 10 mM |

In Vitro Cardiomyocyte NO Imaging.

Cardiomyocytes were plated on individual 35-mm-diameter FlexCell membranes (FlexCell International) coated with 50 ug/mL mouse laminin (Invitrogen; 23017–015) at 30,000 cells/membrane. After plating, cardiomyocytes were switched to culture medium (plating medium without serum) and then loaded with the NO-sensitive dye DAF-FM-DA (Molecular Probes; D-23842). Cardiomyocytes on FlexCell membranes were incubated in imaging buffer (Table S2) containing 20 µM DAF-FM-DA for 40 min in the dark at 37 °C. Cardiomyocytes were then washed in fresh imaging buffer without DAF-FM-DA for 20 min in the dark at 37 °C, then washed again for 5 min at room temperature. In experiments using enzyme inhibitors, inhibitors or appropriate vehicle controls were added to buffer during this 5-min wash.

Table S2.

Imaging buffer composition (pH 7.4)

| Reagent | Final concentration, mM |

| NaCl | 113 |

| KCl | 4.7 |

| MgSO4 | 1.2 |

| KH2PO4 | 0.6 |

| NaH2PO4 | 0.6 |

| Hepes | 10 |

| NaHCO3 | 1.6 |

| Taurine | 30 |

| Glucose | 20 |

| CaCl2 | 1.2 |

| l-arginine HCl | 0.01 |

Membranes were then loaded into a StageFlexer Jr. stretch chamber connected to a FX-4000T Flexercell Tension Plus system (FlexCell International) and covered with fresh imaging buffer. The stretch chamber was secured on the stage of an Olympus BX51 upright epifluorescence microscope and a 10× field of view was visualized under the FITC channel using a 6% neutral density filter. Images of the same field of view were recorded at 0, 10, 30, and 60 min of 12% 1-Hz stretch or drug treatment.

After imaging, the fluorescence of all rod-shaped, nonfibrillatory cardiomyocytes was quantified using ImageJ, with background fluorescence subtracted. Changes in cellular DAF-FM fluorescence intensity over the 1-h imaging period were expressed as the change in fluorescence over initial (0-min) fluorescence (ΔF/F0). The following inhibitors and other reagents were used in these studies: l-NAME (100 µM; Enzo; ALX- 105–003), SNAP (100 µM; Calbiochem; 487910), vinyl-l-NIO hydrochloride (100 µM; Cayman Chemical; 80330), Compound C (10 µM; Cayman Chemical; 11967), AICAR (2 mM; Cayman Chemical; 10010241), and sodium salicylate (10 mM; Sigma-Aldrich; S2679).

In Vitro Stretch Protocol.

Cardiomyocytes were plated on six-well BioFlex culture plates (FlexCell International) coated with laminin at 30,000 cells/well in plating medium supplemented with 25 µM blebbistatin (Toronto Research Chemicals; B592500).

Stretch for Western Blot Analysis.

After plating, cardiomyocytes were changed to culture medium containing 25 µM blebbistatin and serum-starved for 4 h. BioFlex plates were loaded into a baseplate housed within a tissue culture incubator and connected to a FX-4000T Flexercell Tension Plus system (FlexCell International). Cardiomyocytes were subjected to 15% cyclic stretch at 1 Hz for 0–60 min as described previously (14).

Stretch for cGMP Analysis.

Cardiomyocytes were stretched for 60 min as described above. Stretched cardiomyocytes and nonstretched controls were then washed in DPBS and lysed in 0.1 M HCl for 20 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were stored at −80 °C until use. cGMP concentration in cardiomyocyte lysates was analyzed using a cGMP EIA kit (Cayman Chemical; 581021) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and was normalized to protein concentration based on the DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad; 500-0116).

Drug Treatments for Western Blot Analysis.

Cardiomyocytes were plated on 60-mm tissue cultures dishes coated with laminin in plating medium supplemented with 25 µM blebbistatin. After plating, cardiomyocytes were switched to culture medium containing 25 µM blebbistatin and serum-starved for 4 h. Cardiomyocytes were treated with AICAR or sodium salicylate for 0–60 min.

Cardiomyocyte Lysis for Western Blot Analysis.

After stretch or drug treatment, cardiomyocytes were washed in DPBS and then lysed in ice-cold Triton-X lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Table S3). Lysates were sonicated for 10 s and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 2 min at 4 °C. Lysate supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C until use.

Table S3.

Triton-X lysis buffer composition

| Reagent | Final concentration |

| NaCl | 150 mM |

| Tris pH 7.5 | 50 mM |

| Triton X-100 | 1% |

| EDTA | 1 mM |

| Benzamidine | 0.6 mM |

| PMSF | 0.4 mM |

| Pepstatin | 0.5 μg/mL |

| Aprotinin | 2 KIU/mL |

| Leupeptin | 1 μg/mL |

| NaF | 50 mM |

| Sodium orthovanadate | 1 mM |

| Sodium pyrophosphate | 10 mM |

Heart Collection and Tissue Preparation for Western Blot Analysis.

Hearts were collected from anesthetized mice. The atria and large vessels were removed, and the ventricles were drained of blood, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Approximately 50 mg of tissue per heart was added to ice-cold Triton-X lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, minced with scissors, homogenized, and then sonicated twice for 10 s. Heart lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Lysate supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C until use.

Western Blot Analysis.

Protein concentration in lysates was quantified using the DC Protein Assay. For this, 100 µg protein of each sample was separated on 3–15% (wt/vol) gradient polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore; IPVH00010). Membranes were then blocked in 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk or 5% (wt/vol) BSA (Fisher; BP1600) in Tris-buffered saline + 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at room temperature with the appropriate primary antibody. Primary antibodies included rabbit polyclonal antibodies dystrophin (Abcam; ab15277), phospho-nNOS-serine 1412 (Abcam; ab5583), nNOS (Cell Signaling; 4234), and AMPKα (Cell Signaling; 2532), along with rabbit monoclonal antibodies phospho-AMPKα-threonine 172 (Cell Signaling; 2535), phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase-serine 79 (Cell Signaling; 11818), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Cell Signaling; 3676).

After incubation with primary antibodies, blots were washed three times for 10 min each in TBST and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 111–035-144). Membranes were washed three times for 10 min each in TBST, then exposed using SuperSignal West Pico or Dura chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher; 34080 and 34075). Images of blots were recorded with an Alpha Innotech Western blot documentation system, and band intensities were quantified using AlphaEaseFC software.

Statistics.

All data are presented as mean ± SE. Significance was determined by the Student t test and was set at P < 0.05.

SI Materials and Methods

For immunofluorescence experiments, WT and mdx cardiomyocytes were plated on six-well BioFlex culture plates and stretched for 0–10 min as described for Western blot analysis. After stretching, the cells were fixed for 15 min in 3% paraformaldehyde, washed three times for 5 min each in PBS, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C in block solution consisting of 1× PBS, 5% BSA, 0.5% Triton-X, and 50 mM ammonium chloride. After blocking, the FlexCell membranes with attached cardiomyocytes were excised from wells of the BioFlex culture plates with a scalpel and placed on glass slides. The excised membranes were then incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with the appropriate primary antibodies diluted in block solution without ammonium chloride. Primary antibodies included rabbit polyclonal antibodies nNOS (Cell Signaling; 4234) and AMPKα (Cell Signaling; 2532) and mouse monoclonal MANDRA1 dystrophin (Sigma-Aldrich; D8043).

After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were washed three times for 5 min each in PBS and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies diluted in block solution without ammonium chloride containing DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; D9564). Secondary antibodies were as follows: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen; A-11034), Cy3-conjugated rat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 415–165-166), Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 111–165-144), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 115–546-062).

Membranes were then washed three times for 5 min each in PBS. A glass coverslip was mounted on the top of each membrane using PermaFluor (Thermo Scientific; TA-030-FM). Images were captured using a 60× objective on a Nikon A-1 Spectral confocal microscope.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (Grant 241339, to D.E.M.), the University of Michigan Cardiovascular Research and Entrepreneurship Training Program (to J.F.G.), and the National Institutes of Health (Grant T32 GM008322, to J.F.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1512991112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: The protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51(6):919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery AE. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases: A world survey. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90039-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNally EM, et al. Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy Contemporary cardiac issues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Circulation. 2015;131(18):1590–1598. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J Cell Biol. 1993;122(4):809–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell KP, Kahl SD. Association of dystrophin and an integral membrane glycoprotein. Nature. 1989;338(6212):259–262. doi: 10.1038/338259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohlendieck K, Campbell KP. Dystrophin constitutes 5% of membrane cytoskeleton in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1991;283(2):230–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80595-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, et al. Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 1992;355(6362):696–702. doi: 10.1038/355696a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michele DE, et al. Post-translational disruption of dystroglycan–ligand interactions in congenital muscular dystrophies. Nature. 2002;418(6896):417–422. doi: 10.1038/nature00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muntoni F, Torelli S, Wells DJ, Brown SC. Muscular dystrophies due to glycosylation defects: Diagnosis and therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(5):437–442. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834a95e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller B, Karpati G, Carpenter S. Dystrophin-deficient mdx muscle fibers are preferentially vulnerable to necrosis induced by experimental lengthening contractions. J Neurol Sci. 1990;100(1-2):9–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(8):3710–3714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellorusso C, Crawford RW, Chamberlain JS, Brooks SV. Tibialis anterior muscles in mdx mice are highly susceptible to contraction-induced injury. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2001;22(5):467–475. doi: 10.1023/a:1014587918367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumerson JD, Kabaeva ZT, Davis CS, Faulkner JA, Michele DE. Soleus muscle in glycosylation-deficient muscular dystrophy is protected from contraction-induced injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(6):C1430–C1440. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00192.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabaeva Z, Meekhof KE, Michele DE. Sarcolemma instability during mechanical activity in Largemyd cardiac myocytes with loss of dystroglycan extracellular matrix receptor function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(17):3346–3355. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oak SA, Zhou YW, Jarrett HW. Skeletal muscle signaling pathway through the dystrophin glycoprotein complex and Rac1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39287–39295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spence HJ, Dhillon AS, James M, Winder SJ. Dystroglycan, a scaffold for the ERK-MAP kinase cascade. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(5):484–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou YW, Oak SA, Senogles SE, Jarrett HW. Laminin-alpha1 globular domains 3 and 4 induce heterotrimeric G protein binding to alpha-syntrophin’s PDZ domain and alter intracellular Ca2+ in muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288(2):C377–C388. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00279.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okumura A, Nagai K, Okumura N. Interaction of alpha1-syntrophin with multiple isoforms of heterotrimeric G protein alpha subunits. FEBS J. 2008;275(1):22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spinazzola JM, Smith TC, Liu M, Luna EJ, Barton ER. Gamma-sarcoglycan is required for the response of archvillin to mechanical stimulation in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(9):2470–2481. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenman JE, Chao DS, Xia H, Aldape K, Bredt DS. Nitric oxide synthase complexed with dystrophin and absent from skeletal muscle sarcolemma in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1995;82(5):743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang WJ, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase and dystrophin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(17):9142–9147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenman JE, et al. Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and alpha1-syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell. 1996;84(5):757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constantin B. Dystrophin complex functions as a scaffold for signalling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(2):635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai Y, et al. Dystrophins carrying spectrin-like repeats 16 and 17 anchor nNOS to the sarcolemma and enhance exercise performance in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(3):624–635. doi: 10.1172/JCI36612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas GD, Victor RG. Nitric oxide mediates contraction-induced attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1998;506(Pt 3):817–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.817bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau KS, et al. Skeletal muscle contractions stimulate cGMP formation and attenuate vascular smooth muscle myosin phosphorylation via nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1998;431(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas GD, et al. Impaired metabolic modulation of alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(25):15090–15095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi YM, et al. Sarcolemma-localized nNOS is required to maintain activity after mild exercise. Nature. 2008;456(7221):511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature07414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pane M, et al. Long term natural history data in ambulant boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: 36-month changes. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e108205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dedkova EN, et al. Signalling mechanisms in contraction-mediated stimulation of intracellular NO production in cat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;580(Pt 1):327–345. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petroff MG, et al. Endogenous nitric oxide mechanisms mediate the stretch dependence of Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(10):867–873. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bia BL, et al. Decreased myocardial nNOS, increased iNOS and abnormal ECGs in mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31(10):1857–1862. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramachandran J, et al. Nitric oxide signalling pathway in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice: Up-regulation of l-arginine transporters. Biochem J. 2013;449(1):133–142. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson EK, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals new cardiac-specific dystrophin-associated proteins. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojima H, et al. Fluorescent indicators for imaging nitric oxide production. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38(21):3209–3212. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991102)38:21<3209::aid-anie3209>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasuda S, et al. Dystrophic heart failure blocked by membrane sealant poloxamer. Nature. 2005;436(7053):1025–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature03844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forstermann U, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(7):829–837. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou L, Zhu DY. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase: Structure, subcellular localization, regulation, and clinical implications. Nitric Oxide. 2009;20(4):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rameau GA, et al. Biphasic coupling of neuronal nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation to the NMDA receptor regulates AMPA receptor trafficking and neuronal cell death. J Neurosci. 2007;27(13):3445–3455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4799-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fryer LG, et al. Activation of glucose transport by AMP-activated protein kinase via stimulation of nitric oxide synthase. Diabetes. 2000;49(12):1978–1985. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy BA, Fakira KA, Song Z, Beuve A, Routh VH. AMP-activated protein kinase and nitric oxide regulate the glucose sensitivity of ventromedial hypothalamic glucose-inhibited neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297(3):C750–C758. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00127.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen ZP, et al. AMPK signaling in contracting human skeletal muscle: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase and NO synthase phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279(5):E1202–E1206. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas MM, et al. Muscle-specific AMPK β1β2-null mice display a myopathy due to loss of capillary density in nonpostural muscles. FASEB J. 2014;28(5):2098–2107. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-238972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakinuma Y, Zhang Y, Ando M, Sugiura T, Sato T. Effect of electrical modification of cardiomyocytes on transcriptional activity through 5′-AMP–activated protein kinase. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(Suppl 1):S435–S438. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166318.91623.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hao J, et al. Mechanical stretch-induced protection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury involves AMP-activated protein kinase. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;14(1):1–9. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawley SA, et al. Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(44):27879–27887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA, Hardie DG. 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside: A specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur J Biochem. 1995;229(2):558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ljubicic V, et al. Chronic AMPK activation evokes the slow, oxidative myogenic program and triggers beneficial adaptations in mdx mouse skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(17):3478–3493. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jahnke VE, et al. Metabolic remodeling agents show beneficial effects in the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse model. Skelet Muscle. 2012;2(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pauly M, et al. AMPK activation stimulates autophagy and ameliorates muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse diaphragm. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(2):583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawley SA, et al. The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science. 2012;336(6083):918–922. doi: 10.1126/science.1215327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chao DS, Silvagno F, Bredt DS. Muscular dystrophy in mdx mice despite lack of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Neurochem. 1998;71(2):784–789. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crosbie RH, et al. mdx muscle pathology is independent of nNOS perturbation. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(5):823–829. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Budinger GR, et al. Stretch-induced activation of AMP kinase in the lung requires dystroglycan. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39(6):666–672. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0432OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: Rapid mechano-chemotransduction in heart. Science. 2011;333(6048):1440–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1202768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wehling-Henricks M, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Deng B, Tidball JG. Cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient hearts is prevented by expression of a neuronal nitric oxide synthase transgene in the myocardium. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(14):1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adamo CM, et al. Sildenafil reverses cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(44):19079–19083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013077107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung DG, et al. Sildenafil does not improve cardiomyopathy in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(4):541–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.24214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Witting N, et al. Effect of sildenafil on skeletal and cardiac muscle in Becker muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(4):550–557. doi: 10.1002/ana.24216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Percival JM, Anderson KN, Huang P, Adams ME, Froehner SC. Golgi and sarcolemmal neuronal NOS differentially regulate contraction-induced fatigue and vasoconstriction in exercising mouse skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(3):816–826. doi: 10.1172/JCI40736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinberg GR, et al. Whole-body deletion of AMP-activated protein kinase beta2 reduces muscle AMPK activity and exercise capacity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(48):37198–37209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabaeva Z, Zhao M, Michele DE. Blebbistatin extends culture life of adult mouse cardiac myocytes and allows efficient and stable transgene expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(4):H1667–H1674. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]