Significance

Signals emanating from the B-cell receptor (BCR) promote survival of malignant B cells, such as the activated B-cell–like subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Although there is evidence that many lymphoid cancers arise from antigen selected B cells, it is not known whether these malignant cells require ongoing antigenic engagement of the BCR for their survival. In activated B-cell–like DLBCL, we identified key determinants of self-antigen recognition by the BCR that are required to augment the relative viability of these malignant cells. Our findings imply that similar mechanisms may contribute to other B-cell malignancies and suggest precision medicine strategies to identify patients whose cancers may respond to BCR pathway inhibitors, such as ibrutinib.

Keywords: lymphoma, cancer biology, B-cell receptor

Abstract

The activated B-cell–like (ABC) subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) relies on chronic active B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling. BCR pathway inhibitors induce remissions in a subset of ABC DLBCL patients. BCR microclusters on the surface of ABC cells resemble those generated following antigen engagement of normal B cells. We speculated that binding of lymphoma BCRs to self-antigens initiates and maintains chronic active BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL. To assess whether antigenic engagement of the BCR is required for the ongoing survival of ABC cells, we developed isogenic ABC cells that differed solely with respect to the IgH V region of their BCRs. In competitive assays with wild-type cells, substitution of a heterologous V region impaired the survival of three ABC lines. The viability of one VH4-34+ ABC line and the ability of its BCR to bind to its own cell surface depended on V region residues that mediate the intrinsic autoreactivity of VH4-34 to self-glycoproteins. The BCR of another ABC line reacted with self-antigens in apoptotic debris, and the survival of a third ABC line was sustained by reactivity of its BCR to an idiotypic epitope in its own V region. Hence, a diverse set of self-antigens is responsible for maintaining the malignant survival of ABC DLBCL cells. IgH V regions used by the BCRs of ABC DLBCL biopsy samples varied in their ability to sustain survival of these ABC lines, suggesting a screening procedure to identify patients who might benefit from BCR pathway inhibition.

Theory and indirect evidence have supported the notion of antigenic stimulation in the pathogenesis of human B-cell lymphomas for the past half century (1). Human B-cell lymphomas selectively retain expression of the B-cell receptor (BCR) even in the face of frequent chromosomal translocations that disrupt the Ig heavy chain (IgH) locus, suggesting that the signaling pathways emanating from the BCR may sustain the survival of malignant B cells (2). Foreign antigens have been implicated in certain lymphomas, including the hepatitis C virus in splenic marginal zone lymphoma (3) and Helicobacter pylori in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas (4). However, no discernible foreign antigen is present in the majority of lymphoma cases, suggesting a possible role for self-antigens in lymphoma etiology.

Examination of the Ig variable (V) regions has lent further support to the concept of antigen-dependent BCR signaling in lymphoid malignancies. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia, for example, a small subset of germ-line–encoded IgH variable gene (VH) segments are rearranged recurrently (5). The same observation has been made in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), although the recurrent VH segments in these lymphomas are not fully concordant with those in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (6). Nearly one-third of CLL cases use “stereotyped” BCR sequences in which malignant cells from different patients have almost identical IgH V sequences, including the third complementarity determining region (CDR3) that is diversified during VH-DH-JH (VDJ) joining (5). This observation suggests that CLL BCRs may bind to an antigens because CDR regions typically dictate antibody reactivity. Indeed, CLL BCRs can react with many different self-antigens (7), including antigens released by apoptotic cells (8, 9). Additionally, BCRs derived from CLL patients can bind to a conserved epitope within the second framework region (FR2) of their own IgVH (10). Because a large component of the germ-line IgVH repertoire can form antibodies with self-reactivity (11), these findings might merely reflect the derivation of malignant B cells from self-reactive B cells. An alternative, nonmutually exclusive hypothesis is that a self-reactive BCR is essential to maintain the malignant phenotype in an ongoing fashion. This hypothesis has not yet been tested because of the absence of an appropriate model system.

Chronic active BCR signaling drives NF-κB signaling in cell line models of the activated B-cell–like (ABC) subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is essential for their viability (12). Unlike “tonic” BCR signaling (13), which is presumed to be antigen-independent, chronic active BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL has the hallmarks of antigen-dependent BCR signaling in normal B cells (14), including prominent clustering of the BCR on the cell surface (12). Moreover, ∼20% of DLBCL patients have gain-of-function mutations affecting the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) signaling motifs of the BCR subunits CD79A and CD79B, providing genetic evidence that BCR signaling is integral to the pathogenesis of ABC DLBCL (12). Although these mutations increase the amplitude of BCR signaling, they cannot initiate BCR signaling de novo (12), leading us to consider a role for antigen in initiating and maintaining chronic active BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL.

This possibility was supported by a clinical trial in relapsed/refractory DLBCL of ibrutinib, an inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, which links BCR activity to the NF-κB pathway (15). In ABC DLBCL, ibrutinib produced responses in 37% of patients, lengthening their survival. Although ABC DLBCL tumors with CD79A or CD79B mutations responded more frequently to ibrutinib, responses were also observed in 30% of cases without these mutations, suggesting that the BCR activity of these tumors may depend on a nongenetic process, such as self-antigen engagement of the BCR (15). Moreover, ibrutinib has also proved effective in other B-cell malignancies, such as CLL (16), in which no genetic mechanisms of BCR activity have been reported. In the present study, we sought to provide experimental evidence that the IgVH regions of ABC DLBCL BCRs are required for their survival and to elucidate the role of self-antigens in this process.

Results

Restricted IgVH Repertoire in ABC DLBCL.

We first investigated the nature of the rearranged IgVH segments in ABC DLBCL tumors and compared them to those in the other prominent DLBCL subtype, germinal center B-cell–like (GCB) DLBCL, and in normal human B cells. IgVH sequences in DLBCL tumors were assembled from high throughput RNA sequencing data, and classified by ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT)/High V-quest (www.imgt.org/HighV-QUEST) (Dataset S1). Use of IgVH gene segments in normal human B cells was taken from a previous report (17). Remarkably, among 281 ABC DLBCL samples, over 30% used a single IgVH segment, VH4-34. In contrast, the expression of this IgVH segment was significantly less prevalent among 117 GCB DLBCL samples (9%; P < 0.0001), and normal B cells (4%; P = 0.0014) (Fig. 1A). Previous studies also found an enrichment for VH4-34 in limited sets of DLBCL (18) or non-GCB DLBCL cases (19, 20). Besides VH4-34, the only IgVH that was more prevalent in ABC DLBCL than in GCB DLBCL and normal B cells was VH3-7, which was expressed in 7.8% of ABC DLBCL cases (Fig. 1A). Together, the two ABC-enriched IgVH segments, VH4-34 and VH3-7, constitute ∼39% of all cases, demonstrating that these tumors have a remarkably restricted IgVH repertoire and suggesting shared antigenic reactivity. Of note, VH4-34 and VH3-7 are among the IgVH segments that are overrepresented in CLL (5), suggesting that ABC DLBCL and CLL may derive from B cells with similar specificity. In contrast, GCB DLBCL samples were only modestly enriched for three IgVH segments (VH3-30, VH3-48, and VH4-59) compared with ABC DLBCL and normal B cells, consistent with the fact that this subtype does not typically engage NF-κB through chronic active BCR signaling (12), and seldom responds to ibrutinib (15).

Fig. 1.

IgH analysis of DLBCL tumors. (A) The IgVH repertoire in ABC and GCB DLBCL samples compared with normal naïve B cells. (B) Percentage of IgVH bases mutated in ABC and GCB tumors. (C) IgH constant region isotypes in ABC and GCB DLBCL samples. (D) IgH constant region isotypes in ABC DLBCL cases expressing the indicated VH segments.

The IgVH regions in GCB and ABC DLBCL tumors have typically undergone somatic hypermutation (21), in accord with their putative derivation from germinal center and postgerminal center B cells, respectively (22). In the present set of ABC and GCB tumors, somatic hypermutation altered 8.7% and 9.8% of the IgVH bases, respectively (P = 0.084) (Fig. 1B). However, a substantial number of ABC cases (28 of 281; 10%) had IgVH sequences that diverged by <2% from the nearest germ-line IgVH sequence, which we defined as “nonmutated.” Among these nonmutated ABC cases there was an overutilization of the VH1-69 segment (5 of 16; 31.2%) compared with the remainder of ABC DLBCLs (24 of 265; 9.1%). Of note, VH1-69 is frequently used in the Ig-unmutated form of CLL (5), perhaps indicating a shared origin and BCR reactivity of CLLs and ABC DLBCLs with VH1-69.

The enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase that mediates somatic hypermutation is also responsible for switch recombination from IgM to one of the other IgH classes in germinal center B cells (23). Despite their putative origin from postgerminal center B cells, 80% of ABC DLBCL tumors expressed IgM compared with 34% of the GCB DLBCL tumors (Fig. 1C). This finding is consistent with previous work demonstrating that ABC but not GCB DLBCL tumors have genetic lesions that disrupt the switch μ region of the IgH locus that is necessary for Ig class-switch recombination (19, 24). Of note, the frequency of IgM BCRs among VH4-34+ ABC samples was nearly 90%, which was higher than in VH3-7+ samples (77%) and in all other ABC samples (75%) (Fig. 1D). In normal B cells, IgM and IgG BCRs deliver qualitatively different signals, with IgG-BCR signaling promoting terminal plasmacytic differentiation (25–27). Thus, utilization of the IgM constant region in ABC DLBCL tumors, especially those with VH4-34+ BCRs, may be necessary to block terminal differentiation and favor pathological proliferation.

ABC DLBCL Viability Depends on IgH Variable Region Specificity.

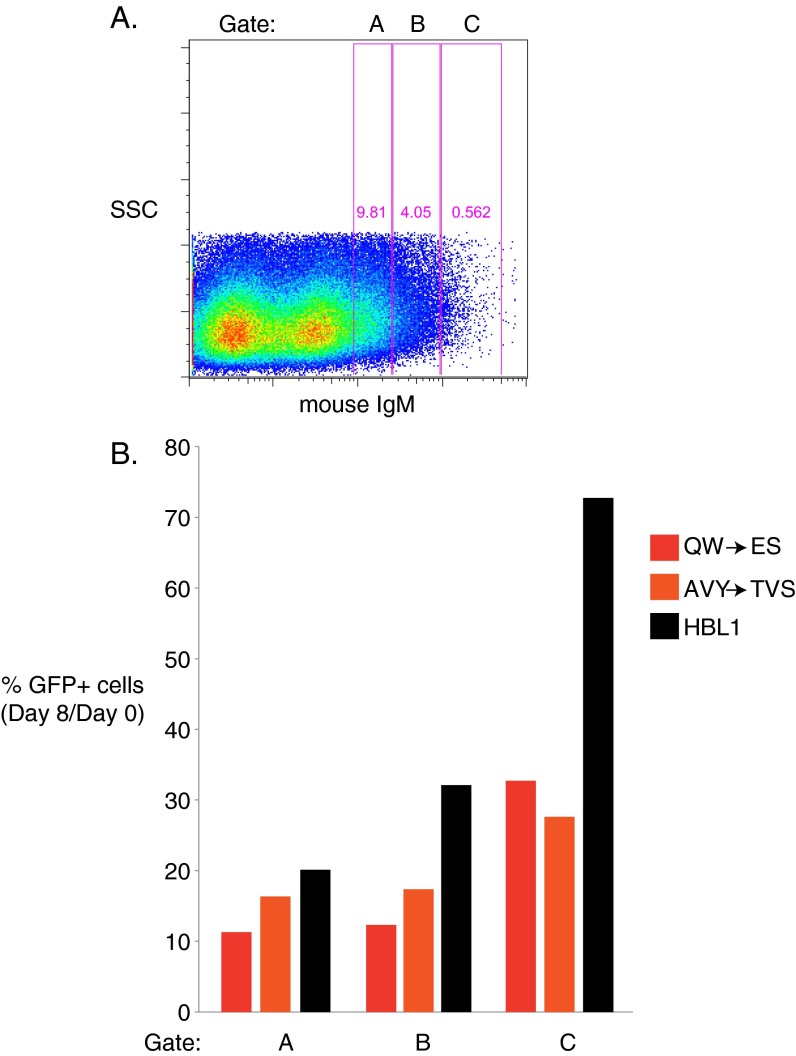

Previous results demonstrated that most ABC lines are dependent on BCR signaling for survival, but the origins of this signaling have been unclear (12). To test the possibility that these lines use the BCR to interact with self-antigens, we developed a knockdown-rescue strategy to create isogenic cell populations with BCRs that differ only in their IgH V regions (Fig. 2A). To do this, ABC lines were concurrently transduced with two vectors, one that coexpresses a doxycycline-inducible small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting human IgM (shIgM) along with GFP, and a “rescue” vector that coexpresses a mouse IgM constant region fused to a human IgH V sequence along with an LYT2 (CD8a) surface marker. Following shRNA induction for 2 d, the proportion of viable, transduced mouse IgM+/GFP+ cells was scored over time by flow cytometry, which evaluates the relative degree of cell death and proliferation of the transduced versus untransduced cells. Previous studies revealed that BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL engages the NF-κB pathway, which primarily functions to inhibit apoptosis but also promotes cell cycle progression (28, 29). For this analysis, we gated on cell populations with equivalent cell surface expression of the transduced murine IgM chains. Because pairing of Ig heavy and light chains is required for cell surface expression of the BCR, this gating ensures that the ectopic mouse IgM chain effectively pairs with the endogenous human Ig light chain. Furthermore, by gating on equivalent surface BCR expression, any functional differences between rescue constructs can be attributed to differences in V-region specificity and not merely to differences in BCR surface abundance. In establishing this system, we noted that the degree of survival of transduced cells was proportional to the level of ectopic mouse IgM expression (Fig. S1), demonstrating the value of gating on defined surface BCR levels in our survival assays.

Fig. 2.

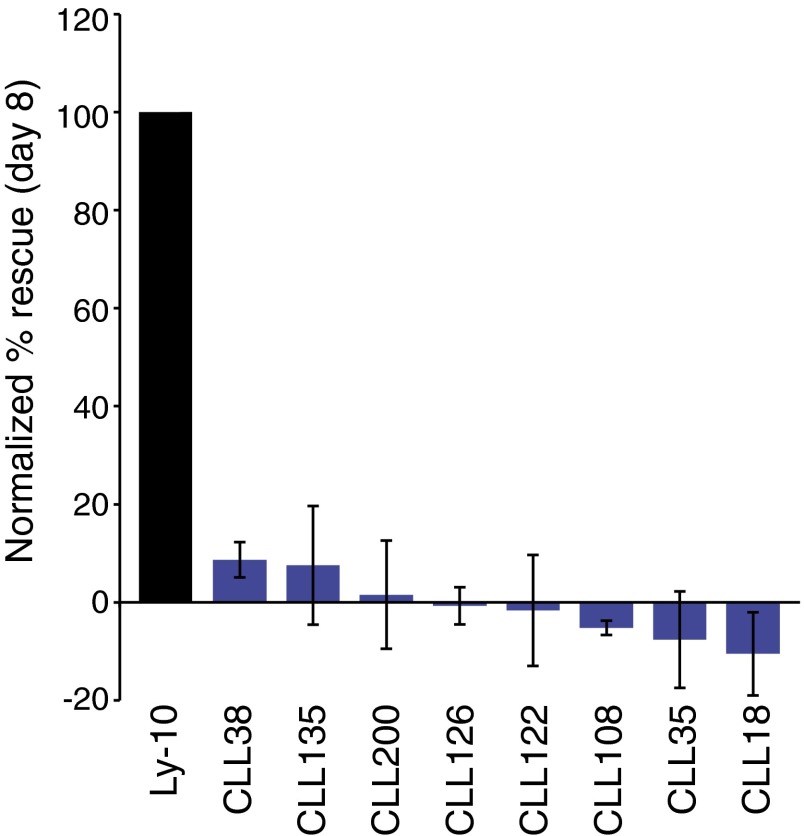

Ectopic expression of IgH chains to determine the role of IgH V regions in maintaining the viability of ABC DLBCL cell lines. (A) A knockdown-rescue strategy to create isogenic ABC cell lines that express different IgH V regions. See Results for details. (B) Ability of the indicated IgH V regions to sustain viability of ABC cell lines following knockdown of endogenous IgM expression. For each indicated ABC cell line, ectopic re-expression of the endogenous IgH V region was most efficient at sustaining survival (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 8). (C) Data from B plotted as the percent rescue of survival at 8 d after shIgM induction: 100% is scaled to the degree of rescue by re-expression of the endogenous IgH V region and 0% is scaled to the degree of rescue by an empty vector.

Fig. S1.

Levels of ectopic mouse IgM expression determine rescue of human IgM knockdown. (A–E) HBL1 cells were cotransduced with a vector expressing shIgM, marked by GFP, and the HBL1 IgH V region fused to mouse IgM. Cells were gated on increasing levels of surface mouse IgM. The amount of GFP+ cells was analyzed on day 0 and day 8, and the percentage of GFP+ cells on day 8, relative to day 0, is shown. Higher levels of surface mouse IgM correlated to increased rescue from toxicity induced by IgM knockdown.

The IgH rescue system was used to evaluate the IgVH dependence of three IgM+ ABC DLBCL lines: HBL1 (VH4-34+), OCI-Ly10 (VH3-7+), and TMD8 (VH3-48+). In cells receiving a control empty rescue vector, shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous IgM expression was toxic, as expected (Fig. 2B). The viability of each cell line was fully or partially rescued by ectopic provision of a mouse IgM chain bearing the V region that is naturally produced by that cell line. Mouse heavy chains bearing different V regions rescued viability less well, or not at all. To quantify these differences, we normalized the data such that the viability of cells at day 8 following transduction with a vector expressing the endogenous IgH V region was set to 100%, and the viability of cells at day 8 following transduction with an empty vector was set to 0% (Fig. 2C). From this representation, it is clear that the OCI-Ly10 cell line has a pronounced preference for the OCI-Ly10 IgH V region. In the HBL1 and TMD8 lines, the self IgH V region was also preferred, whereas some heterologous IgH V regions partially rescued viability and others were inactive. Hence, the mere presence of a BCR on the cell surface is insufficient to sustain survival of these ABC cell lines, implying that the BCR signaling in these ABC cell lines is unlikely to represent “tonic” signaling, which requires the presence of a BCR on the cell surface but not strong antigenic engagement (13).

Self-Antigen Recognition by VH4-34+ BCRs in ABC DLBCL.

VH4–34 is the most frequently used IgH V gene segment in ABC DLBCL (Fig. 1A) and is also prevalent in other BCR-dependent malignancies, including CLL (5, 30) and MCL (6). The ABC cell line HBL1 is BCR-dependent (12) and expresses a VH4-34+ IgH (Fig. 3A). We generated mutants targeting the CDRs of the HBL1 IgH and tested their ability to sustain viability of HBL1 cells using the rescue assay outlined above. Although reversion of the HBL1 CDR1 to the germ-line–encoded VH4-34 sequence had no effect on its ability to rescue viability, reversion of the HBL1 CDR2 to its germ-line sequence caused a moderate (20%) but reproducible impairment, as did reversion of both CDR1 and CDR2 (Fig. 3B). The CDR2 mutation in HBL1 disrupts a motif for N-linked glycosylation (N52H53S54), which is often mutated in normal memory B cells, presumably to improve antigen-binding affinity (31). This motif is frequently altered among VH4-34+ ABC DLBCL tumors, with 59% of IgM cases and 100% of IgG cases acquiring mutations (Fig. 3D). Finally, to probe the function of the HBL1 CDR3 region, we mutated its arginine and aspartic acid residues to alanine. Mutation of all three aspartic acid residues, the arginine alone, or all charged residues had a partial (30–40%) effect on rescue ability in this assay.

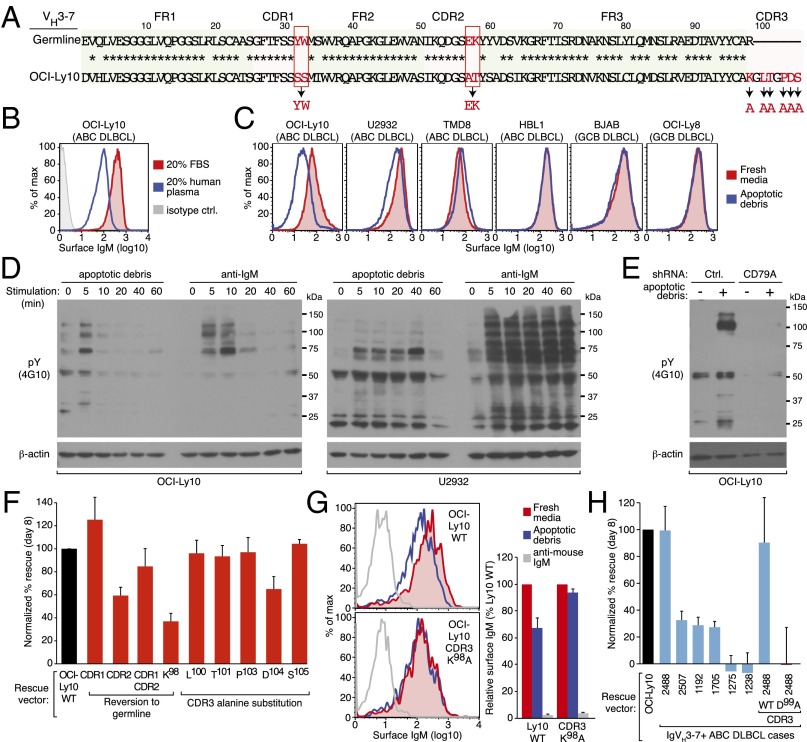

Fig. 3.

Reactivity of VH4-34+ BCRs with self-antigens in ABC DLBCL. (A) The HBL1 IgH V region sequence compared with the germ-line VH4-34 sequence. Mutations introduced in this study are highlighted in red. (B) Substitutions of CDR residues in the HBL1 IgH V region affect HBL1 viability (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (C) Ability of VH4-34+ V regions derived from ABC DLBCL biopsies to sustain HBL1 survival (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (D) Frequency of mutations in ABC DLBCL biopsies targeting the Q6W7 and A24V25Y26 FR1 motifs and the N52H53S54 CDR2 motif in the germ-line VH4-34 gene segment, for ABC cases using either an IgM or IgG constant region. (E) Mutation of the FR1 Q6W7 and A24V25Y26 motifs in the HBL1 IgH V region fail to sustain viability of HBL1 cells (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (F) Mutation of the FR1 Q6W7 motif in a VH4-34+ ABC DLBCL biopsy impairs rescue of HBL1 cells (mean ± SEM, n = 2). (G) FACS analysis of a soluble human IgG1 antibody bearing the HBL1 V region binding to the surface of the indicated ABC DLBCL cell lines. The IgH V region of the recombinant antibody was either identical to the HBL1 IgH V region (WT) or was mutated in the FR1 Q6W7 motif (representative data from three experiments).

The fact that mutations within the CDRs of the HBL1 BCR did not yield a more dramatic impairment in cell survival suggested the possibility that an invariant aspect of VH4-34 might contribute to BCR signaling. Consistent with this possibility, several distinct VH4-34+ sequences derived from ABC DLBCL patient biopsy samples were able to rescue the viability of HBL1 cells (Fig. 3C). The germ-line–encoded VH4-34 sequence confers intrinsic autoreactivity, which is directed against self-antigens on the surface of red blood cells in cold agglutinin disease (32), or B cells in systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) (33). This autoreactivity requires two motifs within the FR1, Q6W7 and A24V25Y26, which in other VH4 family members are instead E6S7 and T24V25S26, respectively (33) (Fig. 3A). Among VH4-34 sequences from IgM+ ABC DLBCL cases, this AVY motif is mutated in only 7% of cases compared with 40% in IgG+ cases (Fig. 3D) (P = 0.056). Similarly, the FR1 QW motif is only mutated in 2% of IgM+ VH4-34+ ABC DLBCL cases (Fig. 3D). This finding implies that the autoreactive potential of VH4-34 is retained in the majority of IgM+ ABC DLBCL cases. Expression of HBL1 heavy-chain constructs in which either of these autoreactive FR1 motifs was mutated to the consensus VH4 family sequence failed to rescue HBL1 survival efficiently (Fig. 3E). The superiority of the wild-type HBL1 IgVH sequence over these FR1 mutant sequences was evident at each level of ectopic mouse IgH expression (Fig. S2). Moreover, mutation of the QW motif in the context of a patient-derived VH4-34 heavy chain completely abrogated its ability to sustain HBL1 viability (Fig. 3F).

Fig. S2.

The wild-type HBL IgVH sequence rescues better than FR1 mutant HBL1 IgVH sequences at all levels of ectopic mouse IgH expression. HBL1 cells were cotransduced with shIgM, marked by GFP, and mouse IgM with a human V region of either wild-type HBL1, HBL1 FR1 QW mutated to ES, or HBL1 FR1 AVY mutated to TVS. (A) Gates were placed on increasing levels of surface mouse IgM. (B) The percentage of GFP+ cells on day 8, relative to day 0, was plotted for each construct in each of the three gates.

The FR1 region of the VH4-34 IgH chain is thought to bind to cell surface glycoproteins that bear the n-acetyl-lactosamine Ii blood group determinant (34). To determine if the HBL1 BCR can bind antigens on the surface of malignant B cells, we prepared a soluble human IgG1 antibody bearing the HBL1 V region, either with or without the IgH FR1 mutation of QW to ES. The HBL1-IgG bound to the surface of three different ABC DLBCL cell lines, including HBL1 itself (Fig. 3G). In contrast, the HBL1-IgG with a mutation disrupting the FR1 QW motif had little if any ability to bind to the surface of these lines. These data indicate that the HBL1 VH4-34 BCR uses its unique FR1 elements to recognize antigens expressed on its own cell surface.

A VH3-7 BCR in ABC DLBCL Recognizes an Antigen Present in Apoptotic Cell Debris.

In addition to VH4-34, the VH3-7 gene segment is used more often in ABC than in GCB DLBCL cases or in normal B cells (Fig. 1A). The ABC cell line OCI-Ly10 is dependent on a VH3-7 IgM-BCR for its survival (Fig. 2B). A serendipitous clue that the OCI-Ly10 BCR binds a self-antigen came from observing its cell surface expression under different culture conditions. OCI-Ly10 cells are typically cultured in 20% (vol/vol) human plasma but can be adapted to grow in 20% (vol/vol) FBS. We detected substantially lower levels of BCR expression on the surface of OCI-Ly10 cells cultured in human plasma compared with those cultured in FBS, suggesting the possibility that human plasma may contain an autoantigen that induces BCR internalization (Fig. 4B). Given that plasma contains debris from apoptotic cells, especially in patients with SLE (35), and that autoantigens from apoptotic cells can bind some BCRs in CLL (9), we tested whether the OCI-Ly10 BCR reacts to antigens present in apoptotic debris, created as described previously (9). Provision of apoptotic debris to OCI-Ly10 cells reduced surface BCR expression after overnight incubation, which was also true for the ABC cell line U2932, but not for other ABC lines (HBL1, TMD8) or for two GCB cell lines (Fig. 4C).

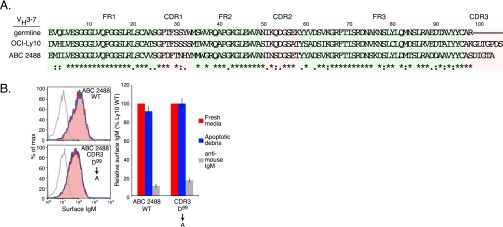

Fig. 4.

Reactivity of ABC DLBCL BCRs to antigens present in apoptotic debris. (A) Sequence of the OCI-Ly10 IgH V region compared with the germ-line VH3-7 sequence. Mutations introduced in this study are highlighted in red. (B) FACS analysis of surface IgM in OCI-Ly10 cells cultured in FBS or human plasma. (C) FACS analysis of surface IgM expression in the indicated DLBCL cell lines cultured with or without apoptotic cell debris (see SI Materials and Methods for details). (D) Western blot analysis of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (pY 4G10) in OCI-Ly10 (Left) and U2932 (Right) following stimulation with apoptotic debris or anti-IgM (0.5 μg/mL) for the indicated times. (E) Western blot analysis of pY in OCI-Ly10 cells exposed to apoptotic debris as indicated. Cells expressed either an shRNA targeting CD79A or a control shRNA, as indicated. (F) Substitutions of CDR residues affect rescue of OCI-Ly10 viability (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (G) FACS analysis of OCI-Ly10 cells ectopically expressing mouse IgM fused to either the OCI-Ly10 IgH V region (WT) or this V region with a K98A substitution, in the indicated culture conditions (Left); relative mean fluorescence intensity is plotted (Right) (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (H) Rescue by VH3-7+ V regions derived from ABC DLBCL biopsies in OCI-Ly10 cells (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Right two bars indicate the degree of rescue by ABC DLBCL case 2488 (WT) compared with this V region with a D99A substitution in its CDR3 region (mean ± SEM, n = 3).

We next investigated whether apoptotic debris induces BCR signaling by examining tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (p-Tyr) in OCI-Ly10 and U2932 ABC cells. In both lines, exposure to apoptotic debris stimulated brisk tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins, most of which were also phosphorylated upon anti-IgM–induced BCR cross-linking (Fig. 4D). To verify that the apoptotic debris increased p-Tyr levels by engagement of the BCR, we used an shRNA to knock down the expression of the BCR component CD79A in OCI-Ly10 cells, thereby preventing BCR surface expression and signaling (12). In contrast to cells induced to express a control shRNA, CD79A knockdown prevented the increase in p-Tyr levels by apoptotic debris (Fig. 4E). Hence, one or more autoantigens in apoptotic debris appear to interact with the BCR, causing it to signal and internalize.

To determine if the survival of OCI-Ly10 cells depends on the ability of its BCR to bind an antigen, we made a series of mutations in the CDRs of the OCI-Ly10 IgH V region (Fig. 4A). Expression of an OCI-Ly10 IgH in which CDR1 was reverted to the VH3-7 germ-line sequence modestly increased its ability to rescue OCI-Ly10 cells following IgM knockdown (Fig. 4F). In contrast, mutation of the OCI-Ly10 CDR2 to its germ-line configuration significantly reduced its ability to sustain OCI-Ly10 viability, suggesting that this sequence element may contribute to antigen binding (Fig. 4F). Expression of an OCI-Ly10 IgH with both the CDR1 and CDR2 sequences reverted to germ line had an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 4F). We next performed alanine mutagenesis of several residues in the OCI-Ly10 CDR3 region. Mutation of either of the two charged residues within the CDR3 substantially reduced the ability of this heavy chain to maintain OCI-Ly10 survival. Alteration of K98 at the border of CDR3 and FR2, which was likely created by junctional diversification during VDJ recombination, had the greatest effect, reducing rescue efficiency by over 60% (Fig. 4F). These data suggest that nongerm-line–encoded amino acids in the OCI-Ly10 IgH chain may have been selected to sustain chronic active BCR signaling.

Because the OCI-Ly10 IgH construct bearing the CDR3 lysine to alanine substitution was unable to sustain OCI-Ly10 viability, we speculated that it would also be unable to interact with autoantigens present in apoptotic debris. To investigate this, we engineered OCI-Ly10 cells to express mouse heavy chains bearing either the wild-type or K98A mutated IgH V regions. Following shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous IgM expression, cells were incubated overnight with fresh media, apoptotic debris, or anti-mouse IgM antibodies as a positive control. Both the wild-type and mutant OCI-Ly10 BCRs were internalized following anti-mouse IgM cross-linking. In contrast, the wild-type OCI-Ly10 BCR was down-modulated upon provision of apoptotic debris while the K98A isoform was unresponsive (Fig. 4G).

Some but not all VH3-7+ IgH chains derived from ABC DLBCL patient biopsies could sustain OCI-Ly10 viability (Fig. 4H). In the case of one patient-derived IgH V region (ABC 2488) that was particularly efficient in rescuing OCI-Ly10 survival, mutation of an aspartate acid residue in its CDR3 region to alanine abrogated rescue, again suggesting that BCR V region specificity is essential for ABC DLBCL cell survival. However, the CDR3 of ABC 2488 differs substantially from the CDR3 of OCI-Ly10 cells in that it contains no positively charged amino acids (Fig. S3). The cell surface expression of the ABC 2488 BCR was not modulated by apoptotic debris (Fig. S3), suggesting that this V region may sustain the viability of OCI-Ly10 cells by recognizing a different autoantigen than is recognized by the OCI-Ly10 BCR.

Fig. S3.

BCRs containing the VH3-7 ABC 2488 IgH V region rescues do not respond to antigens present in apoptotic debris. (A) Alignment of the germ-line VH3-7 sequence with IgH V region sequences from OCI-Ly10 cells and the ABC 2488 biopsy sample. (B) FACS analysis of IgM expression on the cell surface in OCI-Ly10 cells engineered to express an IgH V region derived from the ABC 2488 biopsy sample or the same V region with a D99A substitution in its CDR3 region. Binding was evaluated in fresh media plus or minus apoptotic debris, or following BCR cross-linking with anti-mouse IgM antibodies. (Left) Representative data from three experiments. (Right) Relative mean fluorescent intensity (error bars indicated SEM).

Anti-Idiotype Reactivity in ABC DLBCL.

Although many ABC DLBCL cases express the VH4-34 or VH3-7 V gene segments, the majority of ABC cases express a nondominant V gene segment yet may nonetheless rely on antigen-dependent BCR signaling for their survival. We therefore examined antigen specificity in the ABC line TMD8, which uses a nondominant VH3-48 IgH V gene segment and relies on BCR signaling for survival (Fig. 5 A and B). Reversion of CDR2 in the TMD8 V region to the VH3-48 germ-line sequence resulted in a slight loss of its ability to rescue TMD8 survival after IgM knockdown (Fig. 5B). In contrast, mutation of charged residues in the CDR3 region to alanine substantially affected its ability to rescue survival, particularly when the sole aspartic acid was mutated to alanine (D99A) (Fig. 5B). Thus, the CDR portions of the TMD8 BCR are critical to its function, suggesting that BCR signaling in TMD8 requires antigen binding.

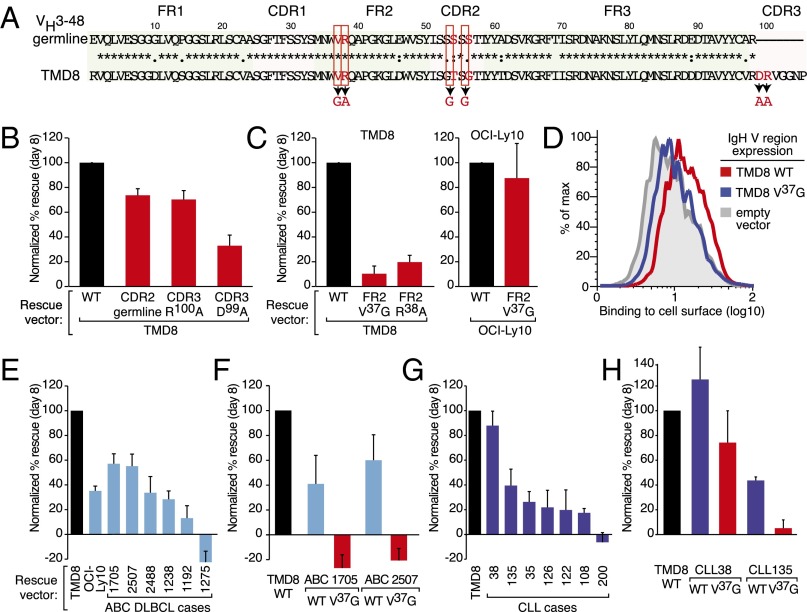

Fig. 5.

Anti-idiotypic reactivity of ABC DLBCL BCRs. (A) Sequence of the TMD8 IgH V region compared with the germ-line VH3-48 sequence. Mutations introduced in this study are highlighted in red. (B) Substitutions of CDR residues in the TMD8 IgH V region affect TMD8 viability (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (C, Left) Substitutions of FR2 residues in the TMD8 IgH V region fail to sustain TMD8 viability. (Right) Substitution of a FR2 residue in the OCI-Ly10 IgH V region maintains OCI-Ly10 viability (mean ± SEM, n = 5). (D) Surface binding of a soluble human IgG1 antibody bearing the TMD8 V region to HBL1 cells transduced with either the IgH V region from TMD8 cells (WT), the TMD8 FR2 V37G, or empty vector, as indicated (FACS plots representative of three experiments). (E) Rescue by VH3-7+ V regions derived from ABC DLBCL biopsies and OCI-Ly10 in TMD8 (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (F) Rescue by ABC DLBCL biopsies with the FR2 V37G substitutions in TMD8 (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (G) Rescue by IgH V regions derived from CLL patient samples in TMD8 (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). (H) Effect of a FR2 V37G substitution in two CLL patient samples on rescue in TMD8 (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3).

Recent work demonstrated that BCRs of CLL cells bind to a V37R38Q39 epitope in their own FR2 domain (10), effectively an idiotope/anti-idiotope interaction (36). TMD8 IgH V regions with mutations targeting this FR2 idiotope (V37G or R38A) were severely crippled in their ability to sustain TMD8 survival (Fig. 5C, Left), implicating a similar mechanism in ABC DLBCL. In contrast, introduction of the V37G mutation into the OCI-Ly10 V region did not affect its ability rescue survival of OCI-Ly10 cells (Fig. 5C, Right). This finding suggests that the V37G mutation does not cause gross misfolding of the IgH chain and is consistent with the fact that the OCI-Ly10 V region recognizes a different antigen in apoptotic cell debris. To show directly that the TMD8 BCR can bind to itself through the V37R38 idiotope, we transduced HBL1 cells with vectors expressing mouse IgM fused to either the wild-type or V37G isoform of the TMD8 V region. After knockdown of endogenous HBL1 IgM, we labeled cells with a soluble TMD8-IgG1 antibody. The TMD8-IgG antibody bound to cells expressing the wild-type TMD8 V region but not to cells expressing the V37G isoform or to cells transduced with an empty vector. These data establish that the TMD8 BCR binds directly to its own FR2 region, thus demonstrating that the TMD8 BCR functions as its own self-antigen.

To determine if ABC DLBCL patient cases use the V37R38 FR2 idiotope as a self-antigen, we assayed seven IgH V regions derived from VH3-7+ ABC patient biopsies for their ability to sustain TMD8 survival. Only two of these IgH V regions rescued TMD8 survival by more than 50% compared with rescue by the TMD8 V region (Fig. 5E). Introduction of the V37G FR2 mutation into these two IgH chains abrogated their ability to rescue viability, demonstrating that this anti-idiotypic mechanism is active in some ABC cases. Because it has been reported that many CLL BCRs signal through this anti-idiotypic mechanism in a mouse pre–B-cell system (10), we tested whether CLL-derived IgH V regions would sustain the viability of ABC cell lines. Among seven VH3-7+ V regions from CLL cases (30), six were able to maintain TMD8 viability, to varying degrees (Fig. 5G), whereas none were able to maintain the viability of OCI-Ly10 cells (Fig. S4). Introduction of the V37G mutation into the two most potent CLL V regions (CLL38 and CLL135) reduced their ability to rescue the viability of TMD8 cells, suggesting that these V regions signal via the anti-idiotypic mechanism (Fig. 5G). However, the V37G isoform of CLL 38 retained substantial activity, perhaps indicating that anti-idiotypic reactivity is not the only way in which this V region promotes BCR signaling.

Fig. S4.

Ability of IgH V regions derived from CLL patient samples to sustain OCI-Ly10 survival (error bars indicate SEM of three experiments).

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that the ongoing, malignant survival of B lymphoma cells can depend critically on the ability of their BCRs to bind self-antigens. Previously, various types of indirect evidence pointed to a potential role for autoreactivity in B-cell malignancies, including the restricted use of particular V regions (5, 6, 30) and the autoreactivity of antibodies derived from malignant B cells (10). However, such data cannot distinguish between autoreactivity that is continuously required for malignant cell survival and autoreactivity that is merely a vestigial remnant of the normal B cell from which the lymphoma arose. By creating isogenic ABC DLBCL cells that differ only in their utilization of particular IgH V regions, we have demonstrated directly that interaction of the BCR with a self-antigen is essential for the survival of these lymphomas cells. We can now understand the previously reported BCR microclusters in the plasma membrane of ABC DLBCL cells (12) as the consequence of self-antigen binding. The present work also illuminates clinical trials that have shown activity of the BCR pathway inhibitor ibrutinib in ABC DLBCL and other B-cell malignancies.

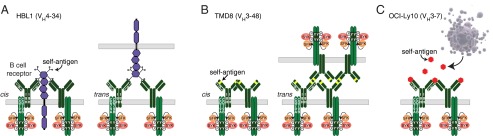

The self-antigens recognized by ABC DLBCL BCRs are diverse and theoretically could either be coexpressed by the same cell as the BCR (“cis” model) or by a neighboring cell (“trans model”) (Fig. 6). In the three ABC lines tested, each IgH V region dictates binding to a different self-antigen (Fig. 6), which is perhaps not surprising given the diversity of autoantibodies that are potentially encoded by germ-line VH segments (11), or acquired somatically during VDJ joining or activation-induced cytidine deaminase-dependent somatic hypermutation (37). Two of the lymphoma BCRs recognized apparently distinct antigens present on their own cell surface. The VH4-34+ BCR of HBL1 cells recognizes a cell surface antigen using FR1 residues that have previously been implicated in binding to n-acetyl-lactosamine chains, suggesting that the self-antigen may be one or more glycoproteins (Fig. 6A). VH4-34+ V regions from patient samples also sustained HBL1 survival in a manner that depended on motifs in the FR1 that confer this autoreactivity. These FR1 motifs are not encoded in other germ-line VH segments, potentially accounting for the fact that nearly one-third of all ABC DLBCL tumors use VH4-34. The cell surface antigen recognized by the BCR of TMD8 cells is the BCR itself: survival of TMD8 cells depended upon an idiotope in the FR2 of the IgH V region, and cells bearing BCRs in which this idiotope was disrupted were not bound by a soluble antibody designed to match the TMD8 BCR (Fig. 6B). This anti-idiotypic mechanism was shared by other IgH V sequences from other ABC DLBCL cases and some, but not all CLL cases, as previously described (10). Chronic active BCR signaling in OCI-Ly10 is apparently driven by yet another self-antigen that is present in apoptotic debris (Fig. 6C). This observation is reminiscent of the autoreactivity to antigens expressed on the surface of apoptotic cells or in their debris that has been described in CLL (8, 9). Histologically, most malignant lymphomas contain evident apoptotic cells, most likely as a byproduct of their disordered regulatory biology, and this dead cell debris could furnish self-antigens that react with some lymphoma BCRs.

Fig. 6.

Models of self-antigen–dependent survival signaling in ABC DLBCL. (A) HBL1 (VH4-34) recognizes self-antigens expressed on the surface of malignant B cells, either in a cis or trans fashion. Binding to self-antigens is potentially mediated through IgH FR1 and CDR3 interactions with n-acetyl-lactosamine glycans attached to cell surface proteins. (B) TMD8 (VH3-48) binds to an idiotope in the IgH FR2 region of its BCR, either in a cis or trans fashion. (C) The OCI-Ly10 (VH3-7) BCR binds to self-antigens released from apoptotic cells.

The interaction of lymphoma BCRs with self-antigens relies in part on the intrinsic autoreactivity encoded in the germ-line VH repertoire. The frequent utilization of VH4-34 in ABC DLBCL cases is consistent with previous work demonstrating an enrichment for VH4-34 among DLBCL cases classified as “non-GCB” by immunostaining (20). Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a type of DLBCL that has an ABC phenotype (38) and acquires several of the pathognomonic mutations of ABC DLBCL (39–42). VH4-34 is used in 55% of PCNSL cases, an enrichment that suggests that this VH segment confers a selective advantage in PCNSL, as in nodal ABC DLBCL. To a lesser extent, VH4-34 use is enriched in CLL (8.9% of cases) and MCL (14.6% of cases) (5, 6), suggesting that the intrinsic autoreactivity of VH4-34 could play a role in these malignancies as well. Although ∼5–10% of naïve B cells have VH4-34+ BCRs, these B cells do not often progress through the germinal center reaction to generate memory B cells and plasma cells (43). The intrinsic autoreactivity of VH4-34+ antibodies to n-acetyl-lactosamine moieties on glycoproteins is presumed to anergize these B cells, potentially accounting for their relative inability to enter productive immune responses. Of the VH4-34+ B cells that do make it into the memory B-cell pool in healthy individuals, 43% acquire mutations that disrupt the FR1 AVY motif that is essential for autoreactivity, presumably as one mechanism to escape anergy (31). In contrast, 93% of the VH4-34 sequences from IgM+ ABC DLBCLs were wild-type for this FR1 motif. Autoreactivity of VH4-34 also requires the FR1 QW motif, which is retained in 98% of VH4-34 sequences from IgM+ ABC DLBCL cases. Together, these findings suggest that most VH4-34+ BCRs in ABC DLBCL retain autoreactivity. Consistent with this notion, experimental mutation of either the AVY or QW motif in the FR1 diminished the ability of the VH4-34+ IgM chains to sustain HBL1 viability and blocked autoreactive binding to the surface of lymphoma cells. Patients with SLE have an increased risk of DLBCL (44, 45), which is notable because the autoreactive potential of VH4-34 antibodies contributes substantially to disease flares in SLE (46). SLE epidemiological studies to date have not distinguished between the ABC and GCB DLBCL subtypes, but our studies would predict that patients with SLE would have a particular predisposition to ABC DLBCL, given the importance of VH4-34 to both diseases.

Lymphoma BCRs also rely on acquired/altered autoreactivity that is a consequence of somatically generated residues in IgH V regions. The activity of the HBL1 VH4-34+ BCR is influenced by a somatic mutation in CDR2 that disrupts an NHS motif for N-linked glycosylation. Attachment of carbohydrate chains to the V region can impair antigen binding, presumably because of steric hindrance (31). Notably, the CDR2 NHS motif is mutated in 60% of IgM+ ABC DLBCL cases, suggesting that this is a frequent mechanism to increase antigen binding by lymphoma BCRs. Consistent with this view, this motif is also mutated in 72% of VH4-34+ PCNSL tumors (47). The phenomenon we observe here appears to be different from the reported increase in BCR signaling attributed to the somatic acquisition of N-linked glycosylation sites in the IgVH sequences from follicular lymphoma (48). The HBL1 BCR also requires charged residues in CDR3 for optimal activity, either to promote reactivity to the same antigens as are recognized using the FR1 motifs or to other antigens. These charged residues are generated by the DH and JH segments and by N-region addition during VDJ joining. In the TMD8 BCR, charged residues in CDR3 are also important for activity, especially D100, which is also generated by junctional diversification during VDJ joining. Finally, the OCI-Ly10 BCR acquired somatic mutations altering residues in CDR2 (A57I58) and in CDR3 (K98), which are required for its ability to promote OCI-Ly10 survival and, in the case of K98, for its ability to interact with self-antigens in apoptotic debris. Thus, in each case, full BCR function requires contributions from somatically generated CDR residues that should be present in only a small minority of normal B cells.

From this perspective, somatically acquired changes in the IgH V regions of B cells could be viewed as one of the earliest genetic events in multistep lymphomagenesis. In some cases, the first oncogenic “hit” may occur in the bone marrow as a result of junctional diversification during VDJ joining and in other cases, the necessary genetic alteration of the V region may occur in the periphery as a result of somatic hypermutation. Thus, although many mature B cells are autoreactive (11), leading to clonal anergy (49), we speculate that only a minority of B cells acquire the particular strength or quality of autoreactivity that is necessary to promote malignant B-cell survival.

Our results provide a fresh perspective on clinical trials of BCR pathway inhibitors in lymphoid malignancies. A recent clinical trial of the BCR pathway inhibitor ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory DLBCL demonstrated significant activity in the ABC but not GCB subtype (15). Within ABC DLBCL, 37% of patients responded, and those whose tumors had gain-of-function mutations targeting the BCR subunit CD79B responded somewhat more frequently. However, most ibrutinib responses in this trial were observed in patients whose tumors had wild-type CD79B, suggesting a nongenetic mechanism for BCR pathway addiction (15). Our present findings suggest that BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL is typically initiated by autoreactivity of the BCR to a self-antigen, and the ensuing chronic active BCR signaling makes the tumors sensitive to ibrutinib. Indeed, the mutant CD79B isoforms that occur in ABC DLBCL cannot initiate BCR signaling de novo, but rather increase the amplitude of already ongoing BCR signaling (12). Ibrutinib also has clinical activity in CLL and MCL, neither of which are characterized by gain-of-function mutations in CD79B (50–52), suggesting that the type of autoreactivity that we describe here may also initiate BCR signaling and maintain viability in these other lymphoid malignancies. Indeed, some but not all CLL IgH V regions were able to sustain the survival of the TMD8 cell line, and this was a result of their self, anti-idiotypic reactivity. Finally, our findings suggest a potential precision medicine approach to optimize the deployment of BCR pathway inhibitors for the therapy of lymphoid malignancies. Specifically, the model systems we have developed could provide a means to gauge whether the IgH V region expressed in a particular tumor is autoreactive in a fashion that can sustain lymphoma survival. Indeed, patient-derived V regions varied considerably in their ability to sustain the survival of our ABC DLBCL models. In the future, it will be interesting to assess whether the autoreactivity measured by these models systems is able to predict which patients will benefit from ibrutinib and other BCR pathway inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

IgH V gene segment sequences were assembled from RNA-seq data using Trinity (53) and processed by IMGT High V-Quest (54). Patient samples were obtained after informed consent and were treated anonymously during RNA-seq analysis. ABC cell lines were grown in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) with 20% heparinized human plasma, penicillin/streptomycin, l-glutamine, and 2-mercaptoethanol. Knockdown-rescue experiments were performed as previously described (12). Additional details are available in the SI Materials and Methods. A complete list of G-blocks used in this study is in Dataset S2.

SI Materials and Methods

IgH V Gene Segment Assembly for ABC and GCB DLBCL.

The RNA-seq paired-end reads (76–103 bp) obtained on either the GAIIX or HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina) were first aligned to RefSeq (Build 37) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner. The remaining reads that did not map to RefSeq were aligned to germ-line segment sequences for human V, D, J, and C using BLAST, and assembled de novo using Trinity (Version July 17, 2014) with default parameters (55). IMGT High V-Quest (v1.3.1) (53) processed the Trinity transcripts based on the conserved cysteine-104 and tryptophan-118. Transcripts with a productive VDJ recombination with an in-frame amino acid junction and complete framework and complementary determining regions were selected. In the instance of multiple productive transcripts or ties, an in-house program selected the transcript best representative of the RNA-seq data.

IgH V Gene for Normal B-Cell Repertoire.

According to Wang et al. (54), peripheral blood IgH repertoires from 27 donors were analyzed using high-throughput DNA sequencing [454 (Roche) platform using Titanium Chemistry]; 323,285 gDNA and 189,915 cDNA sequences were analyzed.

Cell Lines.

ABC cell lines HBL1, OCI-Ly10, and TMD8, engineered to expresses a tetracycline repressor and ecotropic retroviral receptor (12), were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cell lines were grown in IMDM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 20% heparinized human plasma (NIH Blood Bank), penicillin/streptomycin, l-glutamine, and 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies). When noted, cells were grown in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals) instead of human plasma.

Retroviral Vectors.

The vector pRSMX_PuroGFP coexpressing an shRNA, targeting either human IgM or CD79A, with a GFP reporter was previously described (12).

Human V genes were cloned into a modified version of pBMN-IRES-LYT2 (mouse CD8a), engineered to express a mouse IgM constant region with a StuI cloning site to add a human V gene. Murine IgM was amplified from mouse B-cell cDNA using Prime STAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara) with primers: forward: ATCCATTTAAATTCGAATTCCTGAAGGccttcccaaatgtctttccc; and reverse: CGCCGGCCCTCGAGGtcatttcaccttgaacaggg.

The resulting PCR product was inserted into pBMN-IRES-LYT2 that had been digested with StuI (New England Biolabs) by Gibson Cloning (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s directions. The resulting vector was named pBMN-IL-mouseIgM. DLBCL V genes were synthesized as G-blocks (IDT) from available sequence data and inserted into StuI-digested pBMN-IL-mouseIgM by Gibson Cloning. CLL V gene sequences were found in ref. 30. The following overlaps were used for Gibson cloning: 5′ end: ttaaattcgaattcctgcagg and 3′ end: gagagtcagtccttcccaaatgtctttcccc. A complete list of G-blocks used in this study is in Dataset S2.

Knockdown-Rescue Assay.

Retroviral supernatants were generated as previously described (12). ABC lines were sequentially transduced with pRSMX-PG-shIgM expressing an shRNA against human IgM targeting the 3′ UTR, and pMBN-IL-mouseIGM to express a human V gene fused to a mouse IgM constant region. Two days posttransduction, shIgM expression was induced with addition of 100 ng/mL doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich) for day 0 of the assay. Cells were stained with either Alexa647 goat anti-mouse IgM, μ-chain–specific (minimal cross-reactivity) (Jackson Immunoresearch) or Alexa647 anti-mouse CD8a (Biolegend) at 1:1,000 in PBS with 4% BSA for 20 min on ice and analyzed by FACS on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 posttransduction. For analysis, the frequency of GFP+/shIgM+ cells over time was tracked in cells expressing equivalent levels of ectopically expressed mouse IgM or Alexa647 LYT2 (mouse CD8a) for empty vector. Because of variable expression of mouse IgM, a minimum of 200 cells were collected in each gate for inclusion in the dataset.

Production of Human IgG1 Antibodies and FACS Analysis.

ABC V genes were cloned into a soluble human IgG1 and antibodies were produced in 293 cells, as described previously (56). ABC cell lines were stained on ice for 1 h with 0.5 μg/mL of primary antibody in FACS buffer (1% BSA in PBS). Cells were then washed in FACS buffer and stained for 20 min on ice with 0.5 μg/mL goat anti-human IgG-PE (Southern Biotech). Cells were washed in FACS buffer and analyzed on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Data were evaluated with FlowJo (TreeStar).

Apoptotic Debris and BCR Shift Assay.

Apoptotic debris was produced from Kas6 multiple myeloma cell lines by modifying a previously published protocol (9). In brief, Kas6 cells were seeded at 0.5 × 106 cells in RPMI supplemented with 20% FBS. Cells were grown for 4 d, spun down for 10 min at 2,500 × g, and filtered with a 0.45-μm PVDF filter.

To evaluate surface IgM levels on ABC lines, cells were cultured overnight (16 h) in a 1:1 mixture of RPMI with 20% FBS and Kas6 apoptotic debris. Next, 0.5 × 106 cells were washed 3× with FACS buffer, stained with allophycocyanin (APC) anti-human IgM (clone MHM-88) (BioLegend), and analyzed by FACS. To evaluate ectopically expressed human V genes fused to mouse IgM, OCI-Ly10 cells were first cotransduced with shIgM and the mouse IgM construct, as described in the Knockdown-Rescue Assay. Forty-eight hours of doxycycline-induced knockdown of endogenous IgM and cells were stained (see Knockdown-Rescue Assay, above), but with Alexa647 goat anti-mouse IgM, μ-chain specific (minimal cross-reactivity) (Jackson Immunoresearch).

Cell Stimulations.

OCI-Ly10 and U2932 cells were either uninfected or retrovirally transduced and puro-selected for 2 d at 1 μg/mL to uniformly express shCD79A or control shRNA and induced for shRNA expression for 1 d. All cells were passed into fresh RPMI supplemented with 20% FBS overnight. The following morning, cells were spun down (4 min at 1,000 × g) and resuspended in warm RPMI with 20% FBS for 1 h. Cells were again spun down and resuspended in warm RPMI (without FBS) at 2 × 107 cells/mL and placed in Eppendorf tubes in a 37 °C heat block. Cells were then mixed 1:1 with apoptotic debris (50% apoptotic debris final concentration) or 0.5 μg/mL goat anti-human IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch) (final concentration 0.25 μg/mL) for the times listed. At a given time-point, 106 cells were harvested and immediately placed on ice to preserve p-Tyr signal, then spun down at 4 °C for 4 min at 1,000 × g. Supernantants were decanted, cell pellets resuspended in 100 μL of Laemmeli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and stored at −20 °C for later Western blot analysis.

Western Blotting.

For Western blot analysis, 2.5 × 105 cell equivalents of the above lysates were run on a 10% SDS PAGE (Bio-Rad) and transferred to an Immobilon 0.45-μm PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked in 4% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and probed with 4G10 anti-pTyr-HRP (Millipore) in 1% BSA:TBST for 1 h at room temperature, washed in TBST, and developed with Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). Membranes were then stripped with 0.2% NaOH for 10 min and reprobed with anti–β-actin-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) in 1% BSA:TBST for 30 min at room temperature, then developed as before.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study used the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and Center for Cancer Research; and the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung für Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe) (R.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514944112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dameshek W, Schwartz RS. Leukemia and auto-immunization—Some possible relationships. Blood. 1959;14:1151–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Küppers R. Mechanisms of B-cell lymphoma pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(4):251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrc1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinn ER, et al. The B-cell receptor of a hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma binds the viral E2 envelope protein, implicating HCV in lymphomagenesis. Blood. 2001;98(13):3745–3749. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wotherspoon AC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342(8871):575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agathangelidis A, et al. Stereotyped B-cell receptors in one-third of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A molecular classification with implications for targeted therapies. Blood. 2012;119(19):4467–4475. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-393694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadzidimitriou A, et al. Is there a role for antigen selection in mantle cell lymphoma? Immunogenetic support from a series of 807 cases. Blood. 2011;118(11):3088–3095. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hervé M, et al. Unmutated and mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemias derive from self-reactive B cell precursors despite expressing different antibody reactivity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1636–1643. doi: 10.1172/JCI24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catera R, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells recognize conserved epitopes associated with apoptosis and oxidation. Mol Med. 2008;14(11-12):665–674. doi: 10.2119/2008-00102.Catera. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu CC, et al. Many chronic lymphocytic leukemia antibodies recognize apoptotic cells with exposed nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA: Implications for patient outcome and cell of origin. Blood. 2010;115(19):3907–3915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dühren-von Minden M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is driven by antigen-independent cell-autonomous signalling. Nature. 2012;489(7415):309–312. doi: 10.1038/nature11309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301(5638):1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis RE, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;463(7277):88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam KP, Kühn R, Rajewsky K. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90(6):1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolar P, Hanna J, Krueger PD, Pierce SK. The constant region of the membrane immunoglobulin mediates B cell-receptor clustering and signaling in response to membrane antigens. Immunity. 2009;30(1):44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson WH, et al. Targeting B cell receptor signaling with ibrutinib in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):922–926. doi: 10.1038/nm.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrd JC, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd SD, et al. Individual variation in the germline Ig gene repertoire inferred from variable region gene rearrangements. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6986–6992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu FJ, Levy R. Preferential use of the VH4 Ig gene family by diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1995;86(8):3072–3082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruminy P, et al. The isotype of the BCR as a surrogate for the GCB and ABC molecular subtypes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25(4):681–688. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sebastián E, et al. Molecular characterization of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Antigen-driven origin and IGHV4-34 as a particular subgroup of the non-GCB subtype. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(5):1879–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lossos IS, et al. Ongoing immunoglobulin somatic mutation in germinal center B cell-like but not in activated B cell-like diffuse large cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(18):10209–10213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright G, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(17):9991–9996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732008100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Molecular mechanism of class switch recombination: Linkage with somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:165–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenz G, et al. Aberrant immunoglobulin class switch recombination and switch translocations in activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2007;204(3):633–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin SW, Goodnow CC. Burst-enhancing role of the IgG membrane tail as a molecular determinant of memory. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(2):182–188. doi: 10.1038/ni752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horikawa K, et al. Enhancement and suppression of signaling by the conserved tail of IgG memory-type B cell antigen receptors. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):759–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dogan I, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(12):1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U, Staudt LM. Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(12):1861–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam LT, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of IkappaB kinase are selectively toxic for subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma defined by gene expression profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(1):28–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fais F, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(8):1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabouri Z, et al. Redemption of autoantibodies on anergic B cells by variable-region glycosylation and mutation away from self-reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(25):E2567–E2575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406974111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter KN, et al. Molecular characterization of a cross-reactive idiotope on human immunoglobulins utilizing the VH4-21 gene segment. J Exp Med. 1993;178(4):1419–1428. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson C, et al. Molecular basis of 9G4 B cell autoreactivity in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2013;191(10):4926–4939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappione AJ, Pugh-Bernard AE, Anolik JH, Sanz I. Lupus IgG VH4.34 antibodies bind to a 220-kDa glycoform of CD45/B220 on the surface of human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4298–4307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perniok A, Wedekind F, Herrmann M, Specker C, Schneider M. High levels of circulating early apoptic peripheral blood mononuclear cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1998;7(2):113–118. doi: 10.1191/096120398678919804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jerne NK. Towards a network theory of the immune system. Ann Immunol (Paris) 1974;125C(1-2):373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A, Wolfowicz CB, Rothstein TL, Weigert MG. The role of clonal selection and somatic mutation in autoimmunity. Nature. 1987;328(6133):805–811. doi: 10.1038/328805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Camilleri-Broët S, et al. A uniform activated B-cell-like immunophenotype might explain the poor prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphomas: Analysis of 83 cases. Blood. 2006;107(1):190–196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braggio E, et al. Genome-wide analysis uncovers novel recurrent alterations in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(17):3986–3994. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura T, et al. Recurrent mutations of CD79B and MYD88 are the hallmark of primary central nervous system lymphomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/nan.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vater I, et al. The mutational pattern of primary lymphoma of the central nervous system determined by whole-exome sequencing. Leukemia. 2015;29(3):677–685. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada S, Ishida Y, Matsuno A, Yamazaki K. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of central nervous system exhibit remarkably high prevalence of oncogenic MYD88 and CD79B mutations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(7):2141–2145. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.979413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pugh-Bernard AE, et al. Regulation of inherently autoreactive VH4-34 B cells in the maintenance of human B cell tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(7):1061–1070. doi: 10.1172/JCI12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smedby KE, et al. Autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma by subtype. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(1):51–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernatsky S, et al. Lymphoma risk in systemic lupus: Effects of disease activity versus treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):138–142. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tipton CM, et al. Diversity, cellular origin and autoreactivity of antibody-secreting cell population expansions in acute systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(7):755–765. doi: 10.1038/ni.3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montesinos-Rongen M, Purschke F, Küppers R, Deckert M. Immunoglobulin repertoire of primary lymphomas of the central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2014;73(12):1116–1125. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radcliffe CM, et al. Human follicular lymphoma cells contain oligomannose glycans in the antigen-binding site of the B-cell receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(10):7405–7415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quách TD, et al. Anergic responses characterize a large fraction of human autoreactive naive B cells expressing low levels of surface IgM. J Immunol. 2011;186(8):4640–4648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quesada V, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations of the splicing factor SF3B1 gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2012;44(1):47–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beà S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations and clonal evolution in mantle cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(45):18250–18255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314608110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, et al. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2497–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li S, et al. IMGT/HighV QUEST paradigm for T cell receptor IMGT clonotype diversity and next generation repertoire immunoprofiling. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2333. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang C, et al. Effects of aging, cytomegalovirus infection, and EBV infection on human B cell repertoires. J Immunol. 2014;192(2):603–611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(8):1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiller T, et al. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329(1-2):112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.