Significance

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug, and its consumption constitutes a serious health concern. The psychoactivity of the plant is exerted by its cannabinoid constituents, especially Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which acts by engaging CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Despite the large knowledge accumulated on how THC affects the adult brain, its molecular and functional impact on neuronal development remains obscure. This study demonstrates that remarkable detrimental consequences of embryonic THC exposure on adult-brain function, which are evident long after THC withdrawal, are solely due to the impact of THC on CB1 receptors located on developing cortical neurons. Our findings thus delineate the risk of cannabis consumption during pregnancy and contribute to identify precise neuronal lineages targeted by prenatal THC exposure.

Keywords: cannabis, CB1 cannabinoid receptor, corticospinal, neurodevelopment, seizures

Abstract

The CB1 cannabinoid receptor, the main target of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the most prominent psychoactive compound of marijuana, plays a crucial regulatory role in brain development as evidenced by the neurodevelopmental consequences of its manipulation in animal models. Likewise, recreational cannabis use during pregnancy affects brain structure and function of the progeny. However, the precise neurobiological substrates underlying the consequences of prenatal THC exposure remain unknown. As CB1 signaling is known to modulate long-range corticofugal connectivity, we analyzed the impact of THC exposure on cortical projection neuron development. THC administration to pregnant mice in a restricted time window interfered with subcerebral projection neuron generation, thereby altering corticospinal connectivity, and produced long-lasting alterations in the fine motor performance of the adult offspring. Consequences of THC exposure were reminiscent of those elicited by CB1 receptor genetic ablation, and CB1-null mice were resistant to THC-induced alterations. The identity of embryonic THC neuronal targets was determined by a Cre-mediated, lineage-specific, CB1 expression-rescue strategy in a CB1-null background. Early and selective CB1 reexpression in dorsal telencephalic glutamatergic neurons but not forebrain GABAergic neurons rescued the deficits in corticospinal motor neuron development of CB1-null mice and restored susceptibility to THC-induced motor alterations. In addition, THC administration induced an increase in seizure susceptibility that was mediated by its interference with CB1-dependent regulation of both glutamatergic and GABAergic neuron development. These findings demonstrate that prenatal exposure to THC has long-lasting deleterious consequences in the adult offspring solely mediated by its ability to disrupt the neurodevelopmental role of CB1 signaling.

Recreational cannabis consumption during pregnancy can exert deleterious consequences in the progeny, including anxiety, depression, psychosis risk, and cognitive and social impairments (1, 2). In the last two decades, important advances in our understanding of the endocannabinoid system have paved the way to elucidate the particular neurobiological substrates responsible for some cannabinoid-induced neurological alterations in adult animals and humans (3). The currently accepted scenario is that the CB1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1R), the main target of marijuana-derived cannabinoids, is located presynaptically and, upon engagement by endocannabinoids [2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide], can act as a key neuromodulatory and plasticity-tuning signaling platform at many different mature synapses (4). In fact, CB1R constitutes one of the most abundant and functionally relevant G protein-coupled receptors in several regions of the adult mammalian brain (3, 4).

Manipulation of CB1R function in animal models, either directly or indirectly, by modulating 2-AG or anandamide levels through the main endocannabinoid-synthesizing [diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL) α/β] or degrading enzymes [monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH)], influences key processes of forebrain development, including (i) progenitor cell expansion and neurogenesis, (ii) neuronal and glial specification, and (iii) axonal pathfinding (5–7). Alterations of these developmental processes may conceivably underlie the functional deficits observed in the offspring upon prenatal exposure to THC. A crucial role has been assigned to CB1R in the development of long-range axonal connectivity by regulating corticofugal axon navigation and fasciculation (8, 9). In particular, CB1R is essential for subcerebral projection neuron development, as it regulates the appropriate balance between the transcription factors Ctip2 and Satb2 (10), which is responsible for corticospinal motor neuron (CSMN) specification (11).

In this study, we modeled prenatal cannabis consumption in mice to identify the particular neurodevelopmental substrates responsible for cannabinoid-induced functional alterations that remain overt in adult animals. Administration of THC was conducted during a restricted embryonic time window, coinciding with the active period of glutamatergic neuron generation in the telencephalon (11). To unequivocally assess the role of CB1R signaling in THC-induced alterations, we used CB1R-deficient mice, which were resistant to THC-induced developmental effects. Next, by using a Cre-mediated, lineage-specific, CB1R expression-rescue strategy in a CB1R-null background, we were able to selectively rescue the deficits in CSMN development of CB1R-deficient mice and, in turn, fully restore the susceptibility to THC-induced motor alterations in adulthood. We also found that embryonic THC exposure induced an increase in seizure susceptibility that was mediated by CB1R present in developing dorsal telencephalic pyramidal neurons and forebrain GABAergic neurons. Hence, targeting CB1R with the most prominent marijuana-derived psychoactive compound in a particular neuronal population and time frame during embryonic development can evoke remarkable long-lasting neurological alterations.

Results

Prenatal THC Exposure Interferes with Cortical Projection Neuron Development.

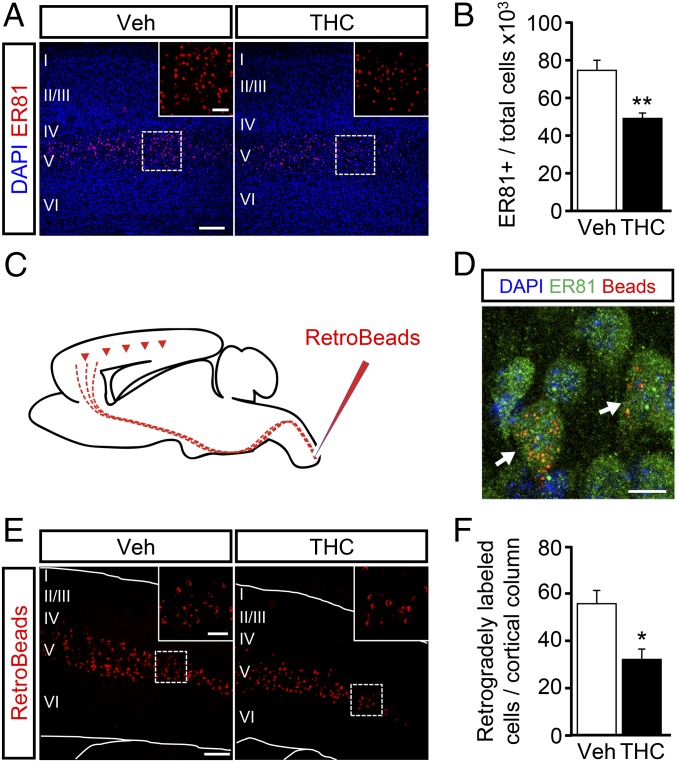

To investigate the impact of prenatal THC exposure on cortical development and to avoid the confounding influence that the cannabinoid could exert during very early gestational stages (12, 13), we administered one daily i.p. injection of THC or its vehicle to pregnant wild-type mice from E12.5 to E16.5. To minimize potential CB1R off-targets, a low dose of THC (3 mg/kg) was used. Of note, maternal and neonate body weight was unaffected by THC treatment, thus indicating that the dose used did not induce deleterious effects on general physical status. As the CB1R is essential for CSMN specification (10), the effects of embryonic THC exposure on the developing cortex were first assessed by quantifying the generation of subcerebral projection neurons. Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of Ets-related protein 81 (ER81), a bona fide marker of subcerebral projection neurons (11), was performed in the treated offspring at P20. ER81+ neurons were decreased in THC-exposed animals compared with their vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1 A and B). The impact of THC on CSMN development was also analyzed at the level of corticospinal axon projections. For this purpose, we performed fluorescent retrograde labeling (Red RetroBeads) from the cervical spinal cord to unequivocally identify CSMNs (14) (Fig. 1C). Red-labeled somata in deep cortical layer V were shown to express ER81, thus confirming the validity of ER81 as an appropriate marker of CSMNs (Fig. 1D). We also found a significant reduction in the number of labeled CSMN somata in THC-treated mice compared with their controls, pointing to an alteration of CSMN development and subcerebral connectivity (Fig. 1 E and F).

Fig. 1.

Embryonic THC exposure impairs subcerebral projection neuron development. (A) Subcerebral projection neurons in embryonically vehicle- and THC-administered mice at P15 were stained with an anti-ER81 antibody (n = 7 and 5, respectively). (B) ER81+ cell number was quantified and referred to the total cell number (DAPI) per cortical column. (C) CSMNs were labeled by injecting retrogradelly transported red fluorescent beads (RetroBeads) in the cervical spinal cord at P10. (D) Representative image showing RetroBead colocalization with the subcerebral projection neuron marker ER81. (E) Representative images of retrogradelly labeled somata in cortical layer V at P15. (F) RetroBead-labeled somata per cortical column were quantified in vehicle- and THC-exposed mice (n = 5 and 4, respectively). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated mice. [Scale bar, (A and E) 200 µm (Insets, 60 µm) and (D) 10 µm.]

Prenatal THC Exposure Induces Long-Lasting Alterations in Skilled Motor Function and Seizure Susceptibility.

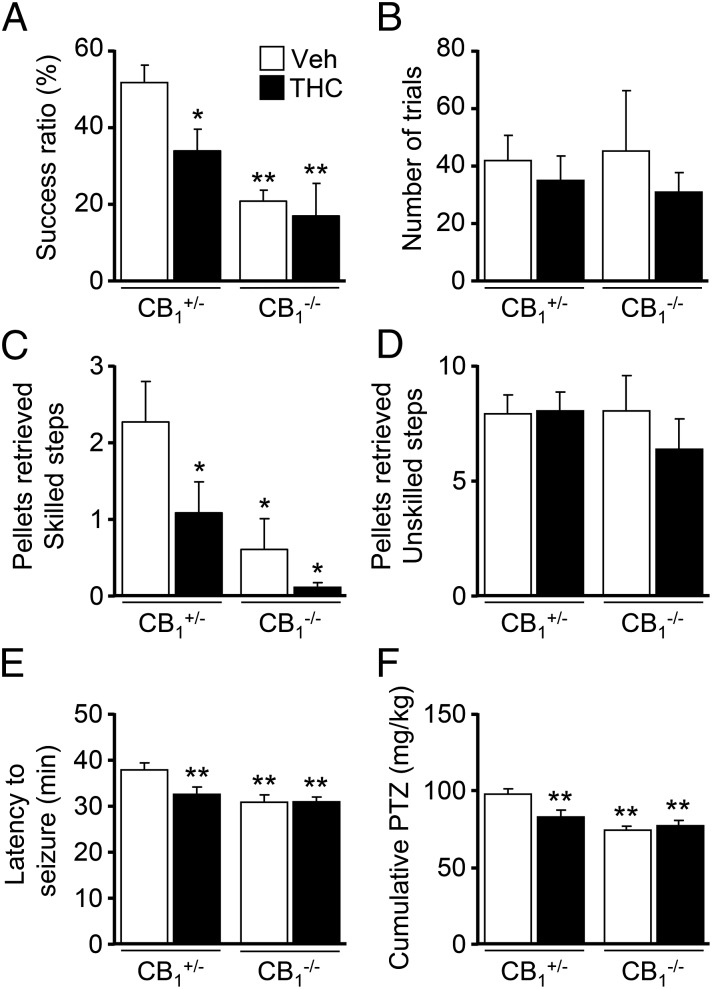

To examine the functional consequences of the impaired subcerebral projection neuron development induced by prenatal cannabinoid exposure, we first used the skilled reaching test, which allows the dissection of CSMN-dependent motor function as reflected by the ability to retrieve a pellet of palatable food with a forelimb through a narrow slit (15). To rule out potential unspecific developmental alterations in the offspring owing to maternal care induced by THC administration (16), we used CB1−/− females, devoid of the behavioral impact of THC, which were mated with heterozygous CB1+/− males. Therefore, we analyzed skilled motor function in the CB1+/− and CB1−/− offspring. CB1+/− mice have been shown to exhibit an increased efficacy of agonist-induced G protein-coupled receptor signaling, which becomes comparable to that of wild-type CB1+/+ mice, thus supporting the validity of this experimental approach (17). THC-exposed CB1+/− animals showed a significant impairment in skilled motor function compared with their vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 2A). Remarkably, CB1−/− mice, which consistently with our previous report showed an impairment in this task compared with their vehicle-treated CB1+/− littermates (10), did not suffer from any worsening in their skilled motor performance upon THC exposure (Fig. 2A). Importantly, neither the number of trials (Fig. 2B) nor the success in unskilled conditions was changed among groups, ruling out generalized motivational or unspecific motor alterations in the observed skilled motor deficits. Corticospinal function was also assessed with the staircase test, and again, a decreased performance was evident in THC-exposed CB1+/− mice compared with their vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 2C). In addition, CB1−/− control mice performed worse than their CB1+/− littermates, and THC treatment did not significantly worsen their ability to reach the pellets. Control quantifications of unskilled reaching did not show significant differences among groups (Fig. 2D). Altogether, these data demonstrate the CB1R dependency of embryonic THC-evoked motor alterations.

Fig. 2.

Embryonic THC exposure impairs corticospinal motor function. (A and B) The skilled pellet-reaching test was evaluated in adult CB1+/− and CB1−/− littermates prenatally exposed to vehicle or THC from E12.5 to E16.5. The success ratio of pellets retrieved in the skilled paradigm (A) and the total number of trials performed (B) were quantified [n = 11 and 8 (CB1+/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 6 and 4 (CB1−/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively)]. (C and D) Mice were subjected to the staircase pellet-reaching test, and the sum of pellets retrieved from skilled steps (from four to eight) was compared between vehicle- and THC-administered mice (C). As a control, the number of pellets reached in unskilled steps 1–3 was calculated (D) [n = 8 and 12 (CB1+/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 5 and 3 (CB1−/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively)]. (E and F) THC- and vehicle-treated CB1+/− and CB1−/− mice were subjected to a PTZ administration paradigm. Latency to tonic-clonic seizure appearance after the first PTZ injection (E) and the cumulative dose of PTZ required (F) were calculated [n = 15 and 18 (CB1+/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 13 and 11 (CB1−/− vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively)]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated CB1+/− mice.

Developmental THC administration induces alterations in synaptic connectivity and plasticity (18, 19), but its long-lasting functional consequences remain largely unknown. Therefore, we analyzed whether seizure susceptibility was affected in the adult offspring of THC-administered pregnant mice by using a pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) administration paradigm. Of note, latency to seizures was significantly decreased in prenatally THC-exposed CB1+/− mice compared with their vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 2E; 31.8 ± 1.4 and 37.0 ± 1.3 min, respectively; P < 0.01). Consequently, a reduced PTZ cumulative dose was required to induce generalized seizures in the THC-treated offspring (Fig. 2F; THC vs. vehicle, 81.3 ± 4.1 and 96.0 ± 3.5 mg/kg, respectively; P < 0.01). This effect of prenatal cannabinoid administration was reminiscent of the adult CB1−/− mice phenotype, which displays increased seizure susceptibility in the kainic acid model (20, 21). Importantly, we found no further enhancement of PTZ susceptibility in THC-treated CB1−/− mice with respect to their vehicle-treated counterparts, thus confirming the CB1R specificity of THC action (Fig. 2F; THC vs. vehicle, 30.2 ± 0.7 and 30.1 ± 1.0 min, respectively). Overall, the neuronal and functional analyses of prenatally THC-administered mice showed a similar phenotype to CB1R-null mice, thus indicating that embryonic THC exposure interferes with the neurodevelopmental role of CB1R signaling.

Prenatal THC Exposure Transiently Impairs CB1R Signaling.

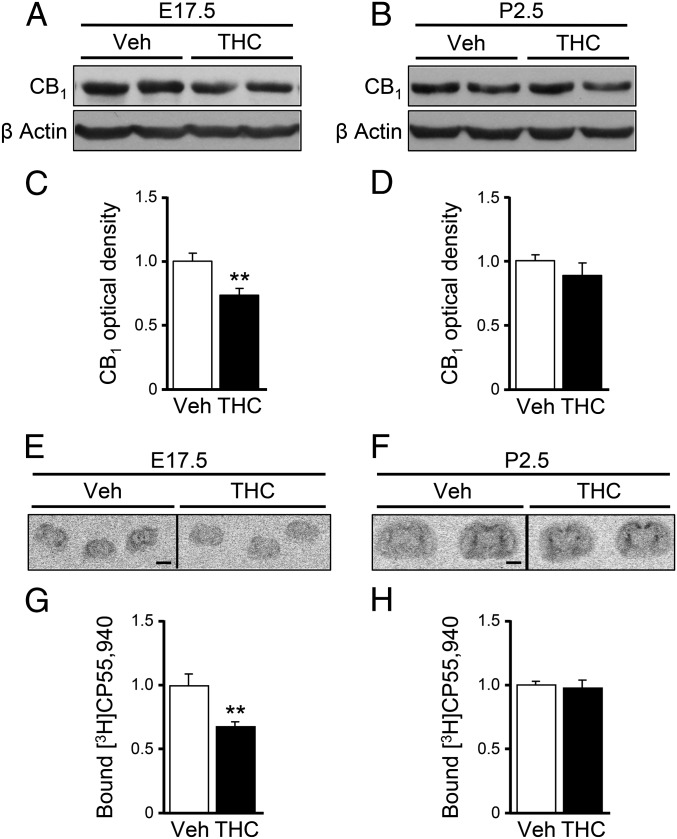

We next analyzed the consequences of prenatal THC administration on CB1R expression. CB1R protein levels, as determined by Western blot, were significantly down regulated in THC-treated embryonic brains at E17.5 compared with controls (Fig. 3 A and C). Notably, at a perinatal stage (P2.5), CB1R levels returned to those of the vehicle condition (Fig. 3 B and D), indicating that CB1Rs are altered only transiently in our embryonic THC-exposure paradigm. The presence of functional plasma membrane-exposed CB1R was next analyzed by the binding of the radioactively labeled CB1R agonist [3H]CP-55,940. A reduced cannabinoid binding was observed in the brains of THC-treated embryos at E17.5 (Fig. 3 E and G), and its values recovered to the level of vehicle-treated animals at P2.5 (Fig. 3 F and H). Overall, these findings support that embryonic THC administration transiently disrupts appropriate CB1R function in the developing brain.

Fig. 3.

Embryonic THC exposure transiently down-regulates CB1Rs. (A–D) CB1R protein levels were determined by Western blot in brain samples at E17.5 (A and C) and P2.5 (B and D) after THC or vehicle administration from E12.5 to E16.5. The optical density of the CB1R band was quantified and normalized to β-actin [n = 9 and 6 (E17.5 vehicle- and THC-treated brain samples, respectively); n = 7 and 7 (P2.5 vehicle- and THC-treated brain samples, respectively)]. (E–H) Radiolabeled CP-55,940 binding was quantified in coronal brain sections at E17.5 (E and G) and P2.5 (F and H) [n = 4 and 6 (E17.5 vehicle- and THC-treated brains, respectively); n = 8 and 8 (P2.5 vehicle- and THC-treated brains, respectively)]. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated mice. (Scale bar, 2 mm.)

Neuronal Lineage-Specific CB1R Reexpression Selectively Rescues the Behavioral Traits of Embryonic THC Exposure.

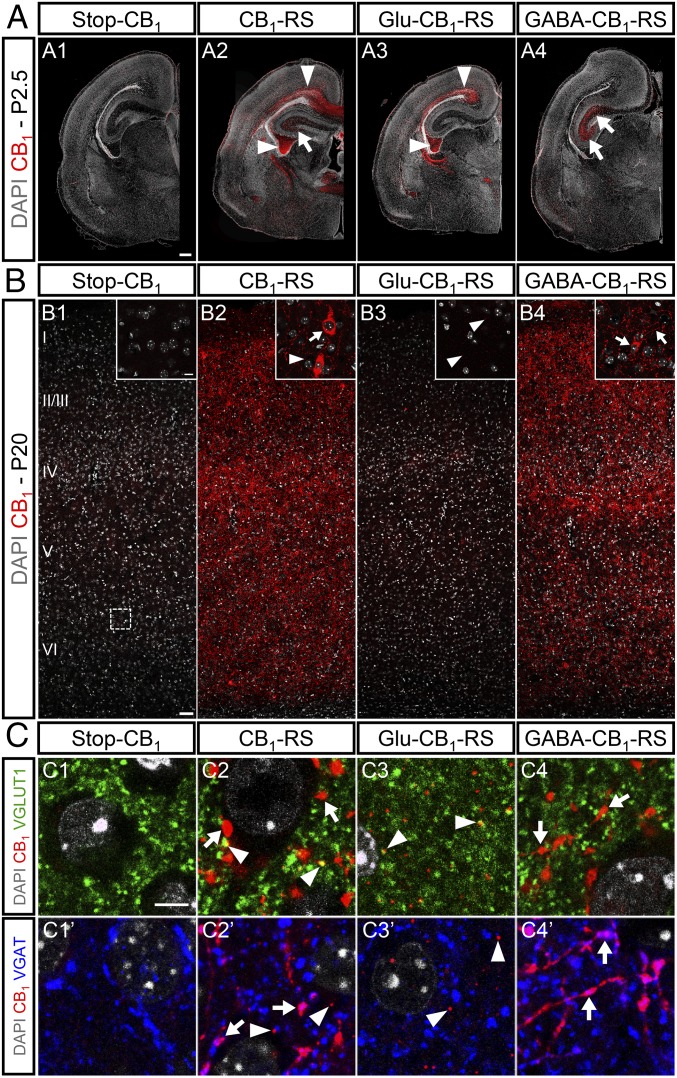

To unequivocally determine the neuronal identity of embryonic THC-exposure actions, we made use of a Cre-mediated, lineage-specific, embryonic CB1R expression-rescue strategy in a CB1R-null background (Stop-CB1 mice) (21). The selective expression of CB1R in dorsal telencephalic glutamatergic neurons (Glu-CB1-RS mice) was achieved by expressing Cre under the regulatory elements of the Nex gene (21). In addition, we rescued CB1R expression in forebrain GABAergic neurons (GABA-CB1-RS mice) by using the Dlx5/6-Cre mouse line (20). As a control, a global CB1R expression rescue approach driven by EIIa-Cre (CB1-RS) was also used (21). Characterization of CB1R expression by immunofluorescence was performed in the different mouse lines. In a Stop-CB1 mice-only background, a nonspecific signal was detected, whereas in Glu-CB1-RS and GABA-CB1-RS animals, CB1R immunoreactivity was observed with a distinctive pattern of expression (Fig. 4 A–C). Glu-CB1-RS mice at P2.5 revealed a significant CB1R expression in descending corticofugal axons, whereas in GABA-CB1-RS mice a prominent CB1R expression was observed in the immature hippocampal formation (Fig. 4 A, A1–A4). Cortical CB1R expression at P20 in Glu-CB1-RS mice appeared as scarce immunopositive puncta, in agreement with the low expression of the receptor in mature projection neurons (4), whereas most CB1R expression corresponded to GABAergic neurons (Fig. 4 B, B1–B4). Double immunofluorescence with VGLUT1 and VGAT, presynaptic markers of glutamatergic and GABAergic terminals, respectively, confirmed the selectivity of the CB1R expression-rescue strategy (Fig. 4C). Thus, in Glu-CB1-RS mice, the small puncta of CB1R did not colocalize with VGAT immunoreactivity, in agreement with their presynaptic location in glutamatergic neurons (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of selective CB1R expression rescue in dorsal glutamatergic neurons and forebrain GABAergic neurons. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of CB1R reexpression driven by Nex (Glu-CB1-RS) (A3), Dlx5/6 (GABA-CB1-RS) (A4), or EIIa (CB1-RS) (A2) promoters in Stop-CB1 mice (A1) was performed in P2.5 coronal brain sections. (B) Cortical CB1R expression analysis in the same mouse strains was performed at P20 (B1–B4). (C) Double immunofluorescence was performed with anti-CB1 antibody combined with anti-VGLUT1 (C1–C4) or anti-VGAT (C1’–C4’) antibodies. Arrowheads point to the glutamatergic CB1R signal, which is abundant in pyramidal neuron fibers at P2.5 (A) and to scarce immunopositive puncta corresponding to glutamatergic (VGLUT1-positive) terminals at P20 (B and C). Arrows point to the abundant CB1R signal corresponding to GABAergic (VGAT-positive) neurons within the hippocampal formation at P2.5 (A) and the mature cortex at P20 (B and C). [Scale bars, (A) 200 µm, (B) 50 µm (Inset, 10 µm), and (C) 5 µm.]

To assess the reestablishment of the neurobiological substrate of THC-induced alterations, we quantified the number of ER81-positive cells in cortical layer V. Remarkably, in vehicle-treated Glu-CB1-RS mice, the number of deep-layer ER81-positive cells per cortical column was significantly rescued compared with Stop-CB1 animals (96.8 ± 6.6 and 71.7 ± 4.9, respectively; P < 0.05), and in concert, Glu-CB1-RS mice gained susceptibility to THC-induced impairment of subcerebral projection-neuron development (73.2 ± 5.5; P < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated Glu-CB1-RS mice).

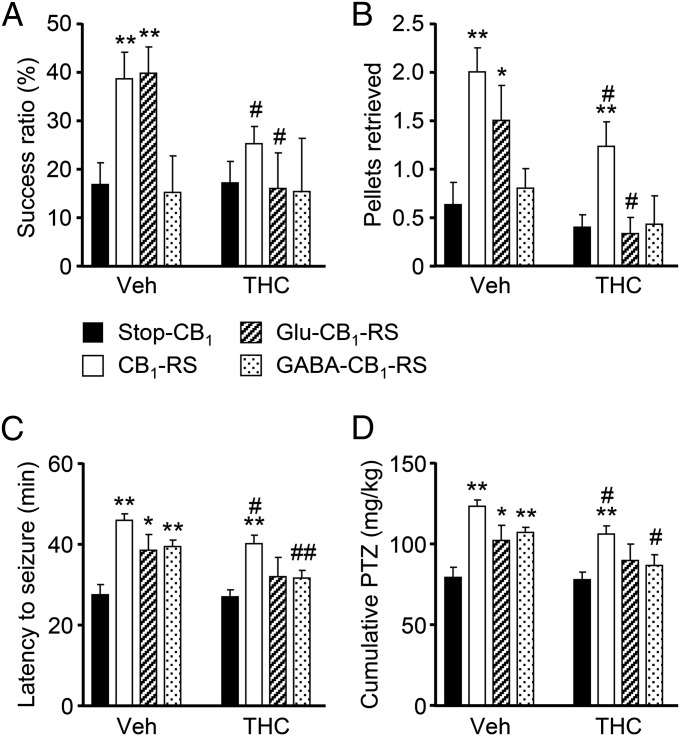

Once the lineage selectivity of the CB1R expression-rescue strategy at the cellular level was proved, we investigated the functional impact of embryonic THC exposure in adulthood. THC or vehicle was administered to pregnant mice coming from crosses of Stop-CB1 with Nex-Cre (Glu-CB1-RS) or Dlx5/6-Cre (GABA-CB1-RS) animals, and their respective offspring were analyzed at an adult age. CB1R reexpression in Glu-CB1-RS mice, but not in GABA-CB1-RS mice, rescued the skilled motor deficits of Stop-CB1 mice as assessed by both the skilled-reaching test (Fig. 5A) and the staircase test (Fig. 5B). Global rescue of CB1R expression in CB1-RS mice also abolished the skilled motor deficits observed in Stop-CB1 mice. Overall, CB1R expression rescue in dorsal telencephalic glutamatergic neurons is necessary and sufficient to confer THC susceptibility to corticospinal motor function.

Fig. 5.

Selective CB1R expression rescue restores functional alterations and reestablishes THC susceptibility in Stop-CB1 mice. (A and B) Skilled motor activity was assessed by the skilled pellet-reaching (A) and staircase (B) tests in adult CB1R-rescued mice [n = 15 and 15 (Stop-CB1 vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 20 and 17 (CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 9 and 6 (Glu-CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 5 and 7 (GABA-CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively)]. (C and D) Seizure susceptibility to subconvulsive doses of PTZ was determined. Latency to seizures (C) and the cumulative dose of PTZ required (D) are shown [n = 13 and 19 (Stop-CB1 vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 18 and 19 (CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 9 and 5 (Glu-CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively); n = 9 and 8 (GABA-CB1-RS vehicle- and THC-treated mice, respectively)]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. corresponding Stop-CB1 mice; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. corresponding vehicle-treated group.

Finally, we also analyzed PTZ-induced seizure susceptibility in the various CB1R expression-rescued mice. Stop-CB1 mice showed a seizure-prone phenotype that was fully restored when the CB1R was expressed systemically in CB1-RS mice, whereas seizure susceptibility was partially restored in both Glu-CB1-RS and GABA-CB1-RS (Fig. 5 C and D; latency to seizures in THC-treated mice, Glu-CB1-RS vs. CB1-RS, 34.0 ± 5.0 and 42.7 ± 2.2 min, respectively, P < 0.05; GABA-CB1-RS vs. CB1-RS, 33.6 ± 2.2 and 42.7 ± 2.2 min, respectively, P < 0.05; cumulative PTZ dose, Glu-CB1-RS vs. CB1-RS, 90.0 ± 10 and 106.6 ± 5.1 mg/kg, respectively, P < 0.05; GABA-CB1-RS vs. CB1-RS, 87.2 ± 6.6 mg/kg and 106.6 ± 5.1 mg/kg, respectively, P < 0.01). Notably, upon THC administration, only CB1-RS mice showed increases in seizure latency and PTZ cumulative dose, whereas no significant differences were found among Stop-CB1, Glu-CB1-RS, and GABA-CB1-RS mice (Fig. 5 C and D). These findings support the notion that prenatal CB1R signaling in both glutamatergic and GABAergic cell lineages is required for the appropriate balance of neuronal activity.

Discussion

The present study reveals that embryonic THC exposure exerts long-lasting consequences in the offspring owing to a transient disruption of CB1R signaling that impedes the adequate temporally and spatially confined function of the receptor in cortical neuron development. Remarkably, the deleterious consequences of prenatal THC exposure in the progeny are independent of the classical neuromodulatory role of CB1R signaling in the adult brain and emerge exclusively as a consequence of the transient disruption of physiological CB1R signaling during prenatal development, when synaptic neuronal activity is not yet established. These findings provide previously unidentified preclinical evidence for the risk of cannabis consumption during pregnancy. Cannabis is, by far, the most commonly consumed illicit drug during pregnancy in Western countries, and therefore its use constitutes a considerable public health issue (1, 2, 16). Over the last few decades, longitudinal studies on human cohorts (1, 2), as well as research using animal models (22), have addressed the impact of early cannabinoid exposure in adulthood. The majority of these studies suggest that early cannabinoid exposure sensitizes the CNS to cognitive impairments, increases the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and anxiety, induces motor alterations, and enhances drug-addiction susceptibility (23–25). Our findings show that exposure to low doses of THC in a narrow temporal window during prenatal development negatively impacts mouse cortical development, and this, in turn, has long-term functional consequences on the mature offspring. Specifically, we unequivocally identify the pool of CB1R located on developing cortical glutamatergic neurons as the sole reason for the deficits in corticospinal function induced by embryonic THC exposure.

The CB1R plays a pivotal neurodevelopmental role by transducing information from the endocannabinoid ligands present in the neurogenic niche into the coordination of the intrinsic developmental program of developing neurons (6, 26). In agreement, early developmental exposure of chicken embryos to a THC analog (27) and genetic manipulation of the CB1R-interacting protein CRIP1 (28) have been shown to disrupt the appropriate balance of transcription factors that intrinsically drive neuronal development. Thus, CB1R signaling refines the molecular, laminar, and hodological identity of projection neurons in the pre- and postnatal cerebral cortex (5, 6). The present findings support that THC can act as a functional suppressor of CB1R signaling, as restricted exposure to THC interferes with developmental CB1R function in a transient but functionally impacting manner. Therefore, prenatal cannabinoid exposure recapitulates the long-term structural and functional deficits in corticospinal connectivity previously demonstrated in CB1R-knockout mice (10). The susceptibility of axonal connectivity to embryonic CB1R loss of function (present report) may persist at later developmental stages in critically susceptible areas, as it has been demonstrated that THC consumption in adolescents can also result in axonal connectivity deficits (29). Nevertheless, in another study, daily marijuana consumption did not induce volumetric changes in several brain areas (30).

Our findings are in partial agreement with a previous study reporting that chronic prenatal THC administration alters neuronal connectivity by disrupting cytoskeletal dynamics in motile axons. Specifically, prolonged THC administration (E5.5 to E17.5) was shown to disrupt cannabinoid signaling by interfering with 2-AG–metabolizing enzymes, MAGL, and DAGL, but did not induce CB1R desensitization (18). In that study, the functional consequences of chronic prenatal THC administration on axonal projections were not determined. Manipulation of endocannabinoid levels in perinatal stages by chronic pharmacological inhibition of FAAH, the main anandamide-degrading enzyme, induced depressive and cognitive impairment traits, despite the fact that no specific neuronal development alterations could be demonstrated (9). On the other hand, pharmacological inhibition of MAGL increased 2-AG levels and induced axon fasciculation alterations by interfering with Slit2/Robo1 signaling, but the functional consequences of these actions remain unknown (31). Other studies have also shown that perinatal cannabinoid administration induces cognitive deficits that can be linked to neuronal transmission adaptations, particularly plasticity of glutamatergic neuron activity (19, 25, 32, 33) and aberrant synaptic organization (18, 34). In humans, prenatal cannabis exposure interferes with executive function (2) and increases children’s depressive symptoms when excluding identified covariate factors such as maternal tobacco use, education, and child composite IQ (35). Moreover, prenatal cannabis exposure interferes with prefrontal cortex-mediated response inhibition as revealed by functional MRI, which may reflect delayed cortical maturation (36). Thus, whereas it is already known that postnatal cannabinoid exposure has negative consequences on neurological functions in the adult brain (1), this study unveils long-lasting functional neuronal alterations induced by restricted prenatal cannabinoid administration that can be unequivocally ascribed to specific developing neuronal lineages. Notably, our findings reveal a direct impact of THC exposure on the developing embryo that does not rely on indirect consequences of maternal programming and that is evident without the requirement of a second hit, as proposed for cannabis-induced risk of psychosis (16). In any case, translating the long-term implications of developmental cannabis exposure into humans requires a very stringent control of confounding factors (37, 38), and this is more important when analyzing cognitive and psychiatric traits than merely determining plastic adaptations of neuronal activity or drug abuse sensitivity.

In addition to corticospinal motor function alterations, embryonic THC exposure increased seizure susceptibility in adult mice, even when CB1Rs return to normal levels shortly after cessation of THC exposure. The neuromodulatory role of CB1R in the mature brain exerts overall an anticonvulsant action (4). In addition, great interest has recently emerged in the potential application of cannabis preparations enriched in cannabidiol for the management of pediatric epilepsy disorders such as Dravet and Gaston–Leroux syndromes (39). However, results presented herein demonstrate that THC interferes with the developmental role of CB1R signaling and induces a proepileptogenic neural circuitry configuration independently of its neuromodulatory role in the adult brain. Our CB1R expression-rescue experiments show that the THC-induced increase in PTZ-evoked seizure susceptibility relies on alterations not only of projection neurons but also of GABAergic neurons. Further investigations are required to underscore the potential contribution of these and perhaps other neuronal lineages targeted by prenatal cannabinoid exposure. In any event, our preclinical observations support that although cannabis preparations can exert anticonvulsive actions in children and adults, they can also enhance the risk of seizures by suppressing CB1R signaling in the developing brain, thus raising a note of caution that might be considered when the potential therapeutic uses of cannabinoid-based medicines are defined and regulated for pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

THC Administration.

Ultrapure THC (≥99% HPLC; THC Pharm) was administered i.p. to pregnant female mice at a final dose of 3 mg/kg for 5 consecutive days from E12.5 to E16.5.

Cellular Analyses and Behavioral Determinations.

CSMN immunofluorescence and retrograde labeling analyses were performed at P20. Skilled motor function (skilled-reaching and staircase) tests were carried out in 2-month-old mice prenatally exposed to THC or its vehicle. Seizure susceptibility was assessed by injecting PTZ (22.5 mg/kg) every 10 min until generalized seizures occurred.

CB1R Biochemical Characterization.

CB1R levels were analyzed by Western blot as well as binding of radiolabeled CP-55,940 in E17.5- and P2.5-treated brain samples.

Genetic CB1R Rescue.

CB1R expression rescue was performed in Stop-CB1 mice by using Nex-Cre, Dlx5/6-Cre, and EIIa-Cre–driven recombination (20, 21). Immunohistological characterization of different CB1R-rescue mice was performed in P2.5 and P20 brain samples. Corticospinal motor function as well as seizure susceptibility were assessed in THC- and vehicle-treated 2-month-old CB1R-rescue mice.

Animals.

Experimental designs and procedures were approved by the Complutense University Animal Research Committee in accordance with the European Commission regulations. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and their suffering throughout the experiments.

Additional experimental procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

Experimental designs and procedures were approved by the Complutense University Animal Research Committee in accordance with the European Commission regulations. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and their suffering throughout the experiments. Mice were maintained in standard conditions, keeping littermates grouped in breeding cages, at a constant temperature (20 ± 2 °C) on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. The generation and genotyping of CB1−/− mice and their respective wild-type littermate controls have been reported elsewhere and were performed accordingly (20). Rescue of CB1R expression in Stop-CB1 mice was performed as described by using Nex-Cre (21), Dlx5/6-Cre (20), and EIIa-Cre–driven recombination (21). Mouse embryonic tissues were obtained upon timed pregnancy as assessed by vaginal plug observation (E0.5). THC (THC Pharm) was diluted in 0.9% NaCl (saline) solution containing 3% (vol/vol) DMSO and 2% (vol/vol) Tween-80 and administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a final dose of 3 mg/kg to pregnant females for 5 consecutive days, from E12.5 to E16.5. Control mice were injected with vehicle solution.

Behavioral Determinations.

THC or vehicle-exposed CB1−/− and CB1+/− littermates (10 wk of age) were tested for skilled-reaching and staircase tests as previously described (10). Control determinations, including the number of trials and the success ratio in unskilled conditions (i.e., the ability to retrieve a pellet at a tongue-reaching distance), were performed. All tests were video-recorded for subsequent analysis and blind quantification. Results shown correspond to the average of two trials for each test. Additional characterization of general motor activity and exploration was performed with ActiTrack (Panlab), which evidenced an absence of major impairments in global motor function. Seizure susceptibility was analyzed by repeated administration of subconvulsive doses of PTZ (Sigma). PTZ was dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered i.p. to 10-wk-old mice at a concentration of 22.5 mg/kg. Mice were placed in Plexiglas cages, video-recorded, and monitored by an experimenter blind to their treatment and genotype. PTZ was administered every 10 min until generalized seizures occurred and latency time and cumulative dose until occurrences of seizures were scored. There was no statistically significant difference in body weight or sex ratio between the different groups of mice.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy.

Adult coronal brain slices (30-μm thick) and perinatal sections (20-µm thick) were processed as previously described (10). Cortical layers were identified by their discrete cell densities as visualized by DAPI counterstaining. Immunofluorescence was performed, after blockade with 5% (vol/vol) goat serum, by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CB1 (1:500, Af530-1; Frontier Institute), ER81 (1:500, ab81086; Abcam), VGLUT1 (1:1,000, 135303C3; Synaptic Systems), or VGAT (1:1,000, 131003; Synaptic Systems), followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies. The appropriate anti-mouse, guinea pig, and rabbit highly cross-adsorbed AlexaFluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used. Confocal fluorescence images were acquired by using Leica TCS-SP2 software (Wetzlar) and an SP2 microscope with two passes by Kalman filter and a 1024 × 1024 collection box. Immunofluorescence of cortical sections was performed, and labeled cells were quantified in a 300-µm-wide cortical column of equivalent sections from the mediolateral area of the motor/somatosensory cortex. At least five independent cortical columns were analyzed per mice.

CSMN Retrograde Labeling.

Deeply anesthetized mice were injected with 0.5 μL of red fluorescent microspheres (RetroBeads, Lumafluor Inc.) into the dorsal funiculus of the cervical spinal cord at P10 and perfused at P15. Brains were sectioned coronally at 30 μm, and CSMNs in the sensorimotor and lateral sensory cortex were counted on every sixth section, across the entire rostro-caudal extent of the cortex, and referred to a 1-mm-wide cortical column.

Immunoblot Assays.

Embryonic brain tissue was collected at E17.5 (i.e., 1 d after the last THC injection) or at P2.5. Protein samples were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein samples were electrophoretically separated and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-CB1R (1:1,000, Af380-1; Frontier Institute) or anti–β-actin (1:5,000, A5441, Sigma) primary antibodies, and the corresponding secondary antibodies were coupled to horseradish peroxidase. The optical density of the relevant immunoreactive bands was quantified with the gel quantification plugin of ImageJ software. The values for CB1R optical density were normalized to those of β-actin in the same membranes.

CB1R Binding Assays.

Binding analysis was performed as described (21). Briefly, perinatal sections were incubated for 3 h at 30 °C in 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, containing 5% (wt/vol) defatted BSA and 5 nM [3H]CP-55,940 (124 Ci/mmol; Perkin-Elmer). Nonspecific binding was determined by incubating adjacent sections in the presence of 10 µM cold CP-55,940 (Tocris Bioscience). After incubation, sections were washed, briefly dipped in distilled water, and dried overnight. Tritium-sensitive phosphor screens were exposed to slides for 3.5 d and scanned using a Cyclone Plus Storage Phosphor System (Perkin-Elmer). Ligand binding to CB1 was quantified from the standard curve compiled by using a tritium standard (American Radiolabeled Chemicals) and Optiquant software (Perkin-Elmer). A minimum of four sections per mice were quantified after subtraction of nonspecific labeling, and the average density was calculated for each animal. Mean values for each condition were expressed relative to those from vehicle-treated animals.

Data Analyses and Statistics.

All variables were first tested for normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s). When variables satisfied these conditions, one-way ANOVA and LSD Fisher post hoc tests were used to assess differences between groups. In other cases, the differences were analyzed by nonparametric (Kruskal–Wallis) tests, and post hoc comparisons by means of Mann–Whitney Wilcoxon test were used to assess differences between groups. Significance level was set below 0.05 in all cases. Results are shown as mean ± SEM, and the number of experiments is indicated in every case. All analyses were carried out using Statgraphics Centurion XVII software (Statpoint Technologies Inc.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena García-Taboada and Eva Resel for technical assistance, Abel Sánchez for statistical analyses guidance, Luigi Bellochio for behavioral determinations advice, and the rest of our lab members for a stimulating scientific and intellectual environment. This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III Grant PI12-00919 (to I.G-R.), German Research Foundation Grant SFB-TRR 58 (to B.L.), Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad Grant SAF2012-35759 (to M.G.), Comunidad de Madrid Grant S2011/BMD-2336 (to I.G.-R.), and Fundación Alicia Koplowitz (to I.G.-R.). J.D.-A., A.d.S.-Q., and D.G.-R. are supported by predoctoral fellowships from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deportes Formación del Profesorado Universitario (FPU) Program; and Complutense University, respectively.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514962112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried PA, Smith AM. A literature review of the consequences of prenatal marihuana exposure. An emerging theme of a deficiency in aspects of executive function. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechoulam R, Parker LA. The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltesz I, et al. Weeding out bad waves: Towards selective cannabinoid circuit control in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(5):264–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maccarrone M, Guzmán M, Mackie K, Doherty P, Harkany T. Programming of neural cells by (endo)cannabinoids: From physiological rules to emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrn3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz-Alonso J, Guzmán M, Galve-Roperh I. Endocannabinoids via CB1 receptors act as neurogenic niche cues during cortical development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1607):3229–3241. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisenberg M, Singh PK, Williams G, Doherty P. The diacylglycerol lipases: Structure, regulation and roles in and beyond endocannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1607):3264–3275. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulder J, et al. Endocannabinoid signaling controls pyramidal cell specification and long-range axon patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(25):8760–8765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803545105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C-S, et al. Requirement of cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in cortical pyramidal neurons for appropriate development of corticothalamic and thalamocortical projections. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32(5):693–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Díaz-Alonso J, et al. The CB(1) cannabinoid receptor drives corticospinal motor neuron differentiation through the Ctip2/Satb2 transcriptional regulation axis. J Neurosci. 2012;32(47):16651–16665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0681-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Menezes JR, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(6):427–437. doi: 10.1038/nrn2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galve-Roperh I, et al. Cannabinoid receptor signaling in progenitor/stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52(4):633–650. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: Clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(3):185–199. doi: 10.1038/nrg1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arlotta P, et al. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45(2):207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomassy GS, et al. Area-specific temporal control of corticospinal motor neuron differentiation by COUP-TFI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3576–3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911792107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvigioni D, Hurd YL, Harkany T, Keimpema E. Neuronal substrates and functional consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(10):931–941. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0550-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selley DE, et al. Agonist efficacy and receptor efficiency in heterozygous CB1 knockout mice: Relationship of reduced CB1 receptor density to G-protein activation. J Neurochem. 2001;77(4):1048–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tortoriello G, et al. Miswiring the brain: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol disrupts cortical development by inducing an SCG10/stathmin-2 degradation pathway. EMBO J. 2014;33(7):668–685. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mereu G, et al. Prenatal exposure to a cannabinoid agonist produces memory deficits linked to dysfunction in hippocampal long-term potentiation and glutamate release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(8):4915–4920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537849100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monory K, et al. The endocannabinoid system controls key epileptogenic circuits in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2006;51(4):455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruehle S, et al. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor in dorsal telencephalic glutamatergic neurons: Distinctive sufficiency for hippocampus-dependent and amygdala-dependent synaptic and behavioral functions. J Neurosci. 2013;33(25):10264–10277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4171-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider M. Cannabis use in pregnancy and early life and its consequences: Animal models. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(7):383–393. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szutorisz H, et al. Parental THC exposure leads to compulsive heroin-seeking and altered striatal synaptic plasticity in the subsequent generation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(6):1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonon KE, Richardson GA, Cornelius JR, Kim KH, Day NL. Prenatal marijuana exposure predicts marijuana use in young adulthood. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2015;47:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubino T, et al. Adolescent exposure to THC in female rats disrupts developmental changes in the prefrontal cortex. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;73:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butti E, et al. Subventricular zone neural progenitors protect striatal neurons from glutamatergic excitotoxicity. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 11):3320–3335. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Psychoyos D, Hungund B, Cooper T, Finnell RH. A cannabinoid analogue of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol disrupts neural development in chick. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2008;83(5):477–488. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng X, Suzuki T, Takahashi C, Nishida E, Kusakabe M. cnrip1 is a regulator of eye and neural development in Xenopus laevis. Genes Cells. 2015;20(4):324–339. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zalesky A, et al. Effect of long-term cannabis use on axonal fibre connectivity. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 7):2245–2255. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiland BJ, et al. Daily marijuana use is not associated with brain morphometric measures in adolescents or adults. J Neurosci. 2015;35(4):1505–1512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2946-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alpár A, et al. Endocannabinoids modulate cortical development by configuring Slit2/Robo1 signalling. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4421. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campolongo P, et al. Perinatal exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol causes enduring cognitive deficits associated with alteration of cortical gene expression and neurotransmission in rats. Addict Biol. 2007;12(3-4):485–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonelli T, et al. Prenatal exposure to the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 causes learning disruption associated with impaired cortical NMDA receptor function and emotional reactivity changes in rat offspring. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15(12):2013–2020. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernard C, et al. Altering cannabinoid signaling during development disrupts neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(26):9388–9393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray KA, Day NL, Leech S, Richardson GA. Prenatal marijuana exposure: Effect on child depressive symptoms at ten years of age. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27(3):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AM, Fried PA, Hogan MJ, Cameron I. Effects of prenatal marijuana on response inhibition: An fMRI study of young adults. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26(4):533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogeberg O. Correlations between cannabis use and IQ change in the Dunedin cohort are consistent with confounding from socioeconomic status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(11):4251–4254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215678110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volkow ND, Baler R. Beliefs modulate the effects of drugs on the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(8):2301–2302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500552112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devinsky O, et al. Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55(6):791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]