Abstract

Cannabis is an increasingly popular and controversial drug used worldwide. Cannabis use often begins during adolescence, a highly susceptible period for environmental stimuli to alter functional and structural organization of the developing brain. Given that adolescence is a critical time for the emergence of mental illnesses before full-onset in early adulthood, it is particularly important to investigate how genetic insults and adolescent cannabis exposure interact to affect brain development and function. Here we show for the first time that a perturbation in Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) exacerbates the response to adolescent exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), a major psychoactive ingredient of cannabis, consistent with the concept that gene-environment interactions may contribute to the pathophysiology of psychiatric conditions. We found that chronic adolescent treatment with Δ9-THC exacerbates deficits in fear-associated memory in adult mice that express a putative dominant-negative mutant of DISC1 (DN-DISC1). Synaptic expression of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) is down-regulated in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, critical brain regions for fear-associated memory, by either expression of DN-DISC1 or adolescent Δ9-THC treatment. Notably, elevation of c-Fos expression evoked by context-dependent fear memory retrieval is impaired in these brain regions in DN-DISC1 mice. We also found a synergistic reduction of c-Fos expression induced by cue-dependent fear memory retrieval in DN-DISC1 with adolescent Δ9-THC exposure. These results suggest that alteration of CB1R-mediated signaling in DN-DISC1 mice may underlie susceptibility to detrimental effects of adolescent cannabis exposure on adult behaviors.

Introduction

Most psychiatric illnesses, including schizophrenia, have complex etiologies involving multiple genetic risk factors that may interact with detrimental environmental factors across the lifespan (Caspi and Moffitt, 2006). Accumulating evidence indicates that adolescence is a susceptible period during which environmental stimuli alter developing functions and structures of maturing neural circuitry, contributing to the onset of psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia in early adulthood (Insel, 2010; Jaaro-Peled et al., 2009).

Cannabis use during adolescence is one such environmental factor for the development of psychosis (Bossong and Niesink, 2010; Rubino and Parolaro, 2008; Saito et al., 2013). Cannabis users during adolescence have an increased risk for psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, in comparison to non-cannabis consumers (Andreasson et al., 1987; Arseneault et al., 2002; Henquet et al., 2005; van Os et al., 2002). In addition, the prevalence of first break psychosis and prodromal symptoms of psychosis is higher for adolescent cannabis users (Di Forti et al., 2009; Leeson et al., 2012; Miettunen et al., 2008). Notably, with the decriminalization and even legalization of marijuana in several countries, including the United States, usage has become more commonplace, outpacing even tobacco consumption among adolescents (Johnston et al., 2014). Nonetheless, not all cannabis users develop psychosis, suggesting that there may be a genetic predisposition interacting with adverse effects of cannabis. Consistently, preclinical studies showed that mice with genetic mutation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and neuregulin 1, genetic risk factors for psychiatric conditions, exhibited greater responses to adverse effects of cannabinoids in cognitive behaviors (Long et al., 2013; O’Tuathaigh et al., 2010).

Here we extend this line of research to evaluate for the first time the role of another genetic risk factor, disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) (Brandon and Sawa, 2011; Kamiya et al., 2012). We assessed the effect of chronic administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the main psychoactive component of cannabis, during adolescence in a transgenic mouse model of DISC1. In this mouse model, a putative dominant negative mutant form of DISC1 (DN-DISC1) is expressed under the control of the αCaMKII promoter in forebrain pyramidal neurons (Hikida et al., 2007), including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus (HPC), and amygdala (AMG), critical brain regions for cognition and emotion (Gilmartin et al., 2014; Marek et al., 2013; Tronson et al., 2012), which are regulated by the endocannabinoid system (Laviolette and Grace, 2006; Saito et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2014). Previous studies demonstrated the possible synergistic effects of DISC1 and several environmental factors, such as neonatal immune activation through Poly I:C injection, adolescent isolation stress, and exposure to the environmental neurotoxicant, lead (Abazyan et al., 2014; Ibi et al., 2010; Niwa et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the interaction of cannabis exposure and DISC1 remains to be elucidated. Thus, we aim to investigate whether chronic treatment with Δ9-THC during adolescence in the DN-DISC1 mouse model impairs endocannabinoid signaling, and exacerbates behavioral deficits in adulthood.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Dominant-negative C-terminal-truncated disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DN-DISC1) mice were generated and developed in the pure C57BL/6N background as previously described (Hikida et al., 2007; Jaaro-Peled et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2013). Expression of DN-DISC1 is controlled by the αCaMKII promoter in glutamatergic neurons of the forebrain, including the PFC and HPC (Hikida et al., 2007). After weaning at postnatal day 21 (P21), animals were housed in groups of five in a controlled temperature (21 ± 1 °C) on a 12-hour light-dark cycle and controlled humidity settings with ad libitum access to food and water. In order to avoid any effect of sex, we performed all behavioral experiments with male age-matched homozygous DN-DISC1 mice and wild type control mice (Johnson et al., 2013), according to the University’s Animal Care and Use Committee’s guidelines in the Johns Hopkins University Brain Science Institute’s Behavioral Core. All tests were conducted by using our previously published methods with minor modifications (Niwa et al., 2010; Zoubovsky et al., 2011).

Chronic Δ9-THC exposure

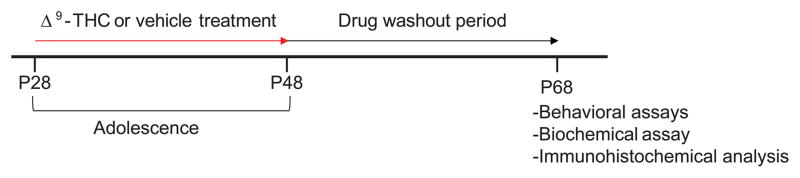

Animals were treated by a previously published paradigm (O’Tuathaigh et al., 2010). Animals were given subcutaneous (SC) injections of 8 mg/kg of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) each day for 21 days from postnatal day 28 (P28) to P48, to simulate chronic Δ9-THC exposure during adolescence (Fig. 1). Δ9-THC solution was prepared with saline and Cremophor (18:1, saline:Cremophor). A control cohort was treated by injection of a matched saline and Cremophor (Vehicle) mixture. After chronic Δ9-THC treatment and prior to behavioral and biochemical assessment, a drug washout period of 20 days was used, to minimize any direct effects from Δ9-THC treatment.

Fig. 1.

Experimental timeline for chronic adolescent Δ9-THC exposure. Age-matched male DN-DISC1 mice and wild type control mice were treated chronically with Δ9-THC via subcutaneous (SC) injections of 8 mg/kg for 21 days during the adolescent period from postnatal day 28 (P28) to P48. To determine whether adolescence is a critical period for Δ9-THC exposure to affect adult brain function, this was followed by a drug washout period of 20 days to exclude direct effects, after which behavioral and biochemical assays were performed.

Behavioral tests

Y-Maze Test

The Y-Maze consists of three arms of equal length interconnected at 120 degrees. During the first trial, all three arms of the maze are open. Each mouse was placed in the end of one arm (alternating pseudo randomly) and allowed to explore freely for 5 minutes. The sequence of arm entries was recorded. Spontaneous alternation behavior is calculated as the number of triads (entries into three different arms consecutively, ABC or BAC, etc.) that contain entries into all three arms divided by the number of possible triads (the total number of visits subtracted by 2).

Novel Object Recognition Test

The novel object recognition test was performed in a Plexiglas open-field arena (25 cm × 25 cm). Each mouse was individually habituated to the arena by allowing it 10 minutes of exploration without objects each day for 3 consecutive days (habituation phase). On Day 4, two identical novel objects were secured on the floor of the arena in adjacent corners, and each animal was allowed to explore the arena for 10 minutes (training phase). Time spent exploring each object was recorded. Twenty-four hours after the training (Day 5), one of the familiar objects used during training was replaced by a novel object similar but not identical in size and color. Each mouse was placed back into the arena and allowed to explore for 5 minutes and the time spent exploring each object was recorded (retention phase). A ratio of the amount of time spent exploring any one of the two objects during the training session, or the novel object during the retention session, over the total time spent exploring both objects was used to measure long term object recognition memory.

Fear Conditioning

Mice were individually placed into a sound-attenuated conditioning chamber with grid floor (18 cm × 18 cm × 30 cm; Coulborn Instruments, PA). On the training day (Day 1), subjects were habituated to the chamber for 180 seconds, before the onset of a tone (2000 Hz) that lasted for 20 seconds (CleverSys, Inc., VA), which co-terminated with a footshock (0.5 mA) lasting for 2 seconds. On Day 2, contextual conditioning was assessed by recording freezing behavior (CleverSys, Inc) during a 300-second exposure to the fear conditioning chamber without any stimulus. On Day 3, cued conditioning was analyzed by recording freezing behavior for 300 seconds in a novel context consisting of a white box cleaned with acetic acid instead of ethanol, with altered cage dimensions, color, and smell, by exposing the animals to the tone presented for 180 seconds starting at 120 seconds. Freezing was defined as a complete lack of movement except for respiration. Contextual fear conditioning prior to c-Fos immunohistochemistry followed the method described above with the following modifications. On Day 1, mice were habituated to the conditioning chambers for 5 minutes, with no tone or shock presented. On Day 2, no tone was presented, and a single footshock (0.5 mA) lasting for 2 seconds was given at 198 seconds. Mice were in the chamber for a total of 5 minutes. Day 3 assessed contextual fear by measuring freezing behavior for 5 minutes in the chamber with no presentations of shock or tone. Cued fear conditioning prior to c-Fos immunohistochemistry followed the method described above with the following modifications. On Day 1, mice were habituated to the conditioning chambers for 5 minutes, with no tone or shock presented. On Day 2, a tone was presented at 180 seconds, lasting for 20 seconds and co-terminating with a footshock (0.5 mA) lasting for 2 seconds. Mice were in the chamber for a total of 5 minutes. On Day 3, cued conditioning was analyzed by recording freezing behavior for 300 seconds in a novel context, with altered cage dimensions, color, and smell, by exposing the animals to the tone presented for 180 seconds starting at 120 seconds.

Hargreaves Plantar Test

The Hargreaves Plantar Test was used to verify proper nociception in our animal models by testing latency of reaction to thermal stimulation. Thermal tests were conducted with a Plantar Analgesia Meter Model 390G from IITC (Woodland Hills CA) equipped with a glass platform. Mice were placed on a glass platform maintained at 32°C and acclimatized to their environment for 30 minutes for 1 day. On the testing day, mice were habituated for 15 minutes on the glass platform before testing. A focused thermal heat stimulus was delivered from a light source to the plantar surface of the paw for up to 30 seconds. A full leg raise specifically at the site where the heat stimulus was directed was considered a reaction to the thermal stimulus. The average of five tests was used as latency for each mouse, and paws were rotated for each trial.

Biochemistry

Extracted brains from adult mice were micro-dissected to obtain whole PFC and HPC regions. To obtain AMG tissue, whole brains were frozen and sectioned with a cryostat (CM 1850 Leica) to isolate the AMG (Anteroposterior (AP): −0.71 mm to −1.31 mm from bregma) in two 200 μm sections, according to a mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). The AMG region was then collected using a 0.5 mm internal diameter punch tool (World Precision Instruments, Inc.). Tissue was lysed in a lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor mixture) and sonicated to extract protein samples. Biochemical fractionation was conducted by following an established method (Dunah and Standaert, 2001). Briefly, dissected PFC and HPC tissue was dounce-homogenized in TEVP buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor mixture) with 320 mM sucrose. Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant fraction was centrifuged again at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes. The pellet was then lysed hypo-osmotically in TEVP buffer with 35 mM sucrose for 90 seconds, centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 1 hour, and the pellet containing the synaptosomal fraction was resuspended in TEVP buffer to provide synaptic samples. Each protein sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal antibody against cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) (Abcam), mouse monoclonal antibody against FLAG-tag (Transgenic Inc.) and synaptophysin (Sigma). Quantitative densitometric measurement of Western blotting was performed using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

c-Fos staining and Quantitative Analyses

Immunohistochemistry of c-Fos was performed by following our published methods with some modifications (Niwa et al., 2010). Briefly, brains extracted from 4% paraformaldehyde (4% PFA)-perfused mice 90 minutes post contextual fear conditioning trials and post cued fear conditioning trials were then fixed with 4% PFA and PFC, HPC, and AMG sections were obtained at 40 μm with a cryostat (CM 1850 Leica). A mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 2007) was used to select brain regions for measurement; prelimbic cortex (PL) (AP: +1.97 mm to +1.77 mm from bregma), CA1 of the HPC (AP: −1.55 mm to −2.79 mm from bregma), and the basolateral amygdala (BLA) (AP: −0.71 mm to −1.31 mm from bregma). Sections were washed with 1X phosphate buffer saline (1X PBS) for 5 minutes, then incubated in sodium citrate (10 mM, pH 6.0) at 70°C for 30 minutes. After washing with 0.05% TritonX-100 in PBS (3 times, 5 minutes each), sections were incubated in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum with 1% BSA and 0.3% TritonX-100 in PBS) at room temperature for 2 hours. Sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody against c-Fos (Millipore) in blocking solution at 4°C overnight and then with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 568 at room temperature for 1 hour. DAPI (Molecular Probes) was used to visualize nuclei. Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer D1, Zeiss) in a blinded manner and the numbers of c-Fos-positive cells/10−1 mm2 were measured in the regions of interest (PL, CA1, and BLA). Three sections per brain were analyzed from each of four animals per condition.

Statistical analyses and unbiased assessment in experimental procedures

Multiple-group comparisons between DN-DISC1 and control animals as well as Δ9-THC and vehicle treatments were performed by using two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni or Dunnett post-hoc tests with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Experiments, including Δ9-THC treatment, behavioral experiments, as well as biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis were performed by multiple investigators. Investigators conducted these assays blinded with regard to genotype or Δ9-THC treatment.

Results

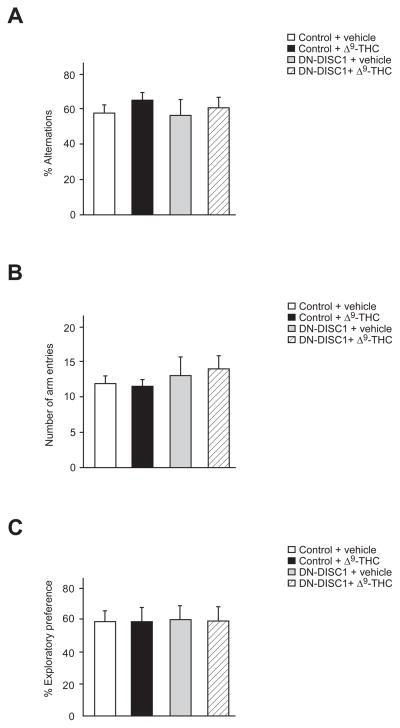

Chronic adolescent Δ9-THC exposure in DN-DISC1 mice does not have a detrimental effect on adult spatial working and object recognition memory

To evaluate cognitive functions in DN-DISC1 mice treated with Δ9-THC chronically during adolescence, we conducted Y-Maze and novel object recognition tests. We found no significant difference in spontaneous alternation due to gene (F = 0.59, df (1, 37), P = 0.6528), treatment (F = 2.48, df (1, 37), P = 0.3581), or interaction (F = 0.17, df (1, 37), P = 0.8065) as assessed in the Y-Maze (Fig. 2A), with no difference in exploratory activity as measured by arm entries (gene (F = 3.15, df (1, 37), P = 0.2982), treatment (F = 0.09, df (1, 37), P = 0.8624), interaction (F = 0.38, df (1, 37), P = 0.7151)) (Fig. 2B). We also found no significant difference in exploratory preference of a novel object among groups as a result of gene (F = 0.01, df (1,41), P = 0.9409), treatment (F = 0.01, df (1,41), P = 0.9477), and interaction (F = 0, df (1,41), P = 0.9701) (Fig. 2C), suggesting that neither DN-DISC1 nor adolescent chronic Δ9-THC exposure had a detrimental effect on proper functioning of long term object recognition memory.

Fig. 2.

No effect of chronic Δ9-THC treatment during adolescence and DN-DISC1 on cognitive functions assessed by Y-maze and novel object recognition tests. No abnormalities due to either chronic Δ9-THC treatment during adolescence or DN-DISC1 expression were observed in percent alternations (A), total number of arm entries (B) during Y-Maze, or novel object preference in novel object recognition test (C). n = 10 per condition. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

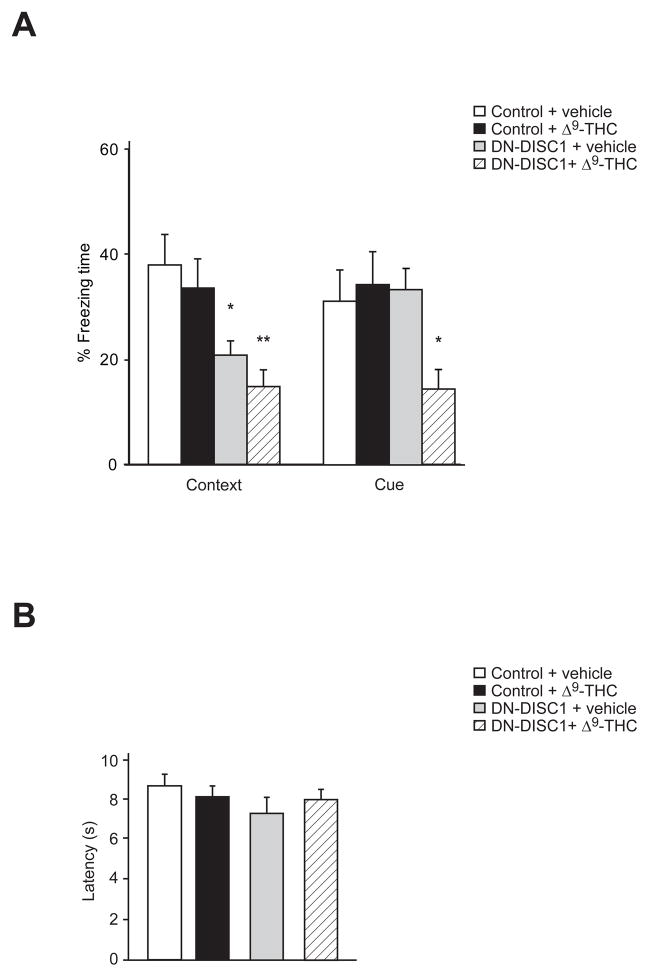

Chronic adolescent Δ9-THC exposure in DN-DISC1 mice impairs adult emotional memory

A growing body of evidence indicates that the endocannabinoid system plays critical roles in multiple aspects of fear regulation (Marsicano et al., 2002; Ruehle et al., 2012; Zanettini et al., 2011). Deficits in fear conditioning in adulthood caused by adolescent treatment with WIN 55,212-2, a CB1R agonist, have been reported (Gleason et al., 2012). To our knowledge, behavioral phenotypes associated with fear memory have not been examined in DN-DISC1 mice. Therefore, we tested the effect of chronic adolescent Δ9-THC exposure on contextual and cued emotional learning in adult DN-DISC1 mice by the fear conditioning test. During the contextual memory test phase, there was a significant effect of gene (F = 17.712, df (1, 36), P = 0.0001), but not treatment (F = 1.139, df (1, 36), P = 0.294) or gene x treatment interaction (F = 0.011, df (1, 36), P = 0.916). Post hoc analyses showed that both Δ9-THC-treated and untreated DN-DISC1 animals displayed significantly decreased freezing behavior, with Δ9-THC-treated DN-DISC1 displaying a slightly lower freezing response when compared with untreated ones (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3A). In the cued memory phase, two-way ANOVA showed a significant gene x treatment interaction (gene (F = 2.455, df (1, 36), P = 0.127), treatment (F = 1.883, df (1,36), P = 0.18, interaction (F = 4.858, df (1,36), P = 0.035)) (Fig. 3A), indicating a synergistic effect of DN-DISC1 and adolescent cannabis exposure on fear memory function in cued conditioning. Note that results of the Hargreaves-Plantar test showed that average latency to removal of a paw under direct focus of a heat source did not differ among groups, confirming proper nociceptive functioning despite gene (F = 8.38, df (1, 33), P = 0.094), treatment (F = 0, df (1, 33), P = 0.981), and gene x treatment (F = 6.88, df (1, 33), P = 0.127) differences (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Convergent effects of chronic exposure to Δ9-THC during adolescence and DN-DISC1 on fear-associated emotional learning and memory. (A) In contextual fear conditioning, significant deficits in contextual freezing were observed in Δ9-THC-treated and untreated DN-DISC1 mice compared with control mice, whereas only Δ9-THC-treated DN-DISC1 mice displayed deficits in freezing behaviors in cued fear conditioning. (B) DN-DISC1 mice and wild type control mice with/without chronic Δ9-THC treatment displayed equal levels of nociception as measured by the Hargreaves-Plantar test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 determined by two-way ANOVA with posthoc test. n = 10 per condition. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

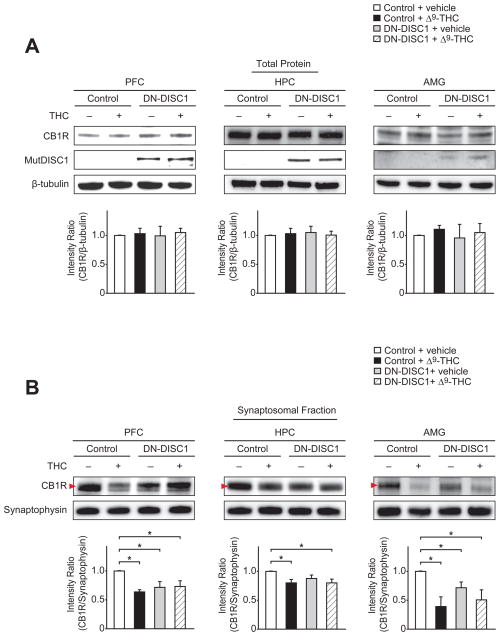

Reduction of synaptic CB1R expression in PFC, HPC, and AMG in adulthood by DN-DISC1 expression and adolescent treatment with Δ9-THC

We next explored whether DN-DISC1 expression and/or adolescent Δ9-THC exposure might alter endocannabinoid signaling, focusing on expression of CB1R which is preferentially expressed in PFC, HPC, and AMG, a major cannabinoid receptor for regulation of cognitive function, including fear-associated memory (Eggan et al., 2009; Tsou et al., 1998). We observed no changes in total CB1R expression in the PFC, HPC, and AMG by either DN-DISC1 expression or adolescent Δ9-THC exposure (Fig. 4A). Synaptic CB1R expression in these brain regions was reduced by adolescent Δ9-THC exposure and synaptic CB1R expression in the PFC and AMG was also decreased in untreated adult DN-DISC1 mice compared with control mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). A similar tendency was observed in the HPC, where synaptic CB1R expression is slightly decreased in DN-DISC1 mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Reduction of synaptic expression of CB1R in adult prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala by DN-DISC1 expression and adolescent treatment with Δ9-THC. (A) Total CB1R expression levels (upper panels) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus (HPC), and amygdala (AMG) were unchanged by either DN-DISC1 expression or chronic treatment with Δ9-THC during adolescence. (B) DN-DISC1 expression reduced synaptic CB1R expression in the PFC and AMG in comparison to wild type controls (arrowhead in upper panels). Chronic Δ9-THC treatment during adolescence decreased synaptic CB1R expression in the PFC, HPC, and AMG of wild type control mice, but had no additional effect on DN-DISC1 mice (arrowhead in upper panels). The densitometry measurement of CB1R signal was normalized to that of β-tubulin (A) or synaptophysin, a synaptic marker protein (B). Bars represent averages of each group in four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 determined by two-way ANOVA with posthoc test. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

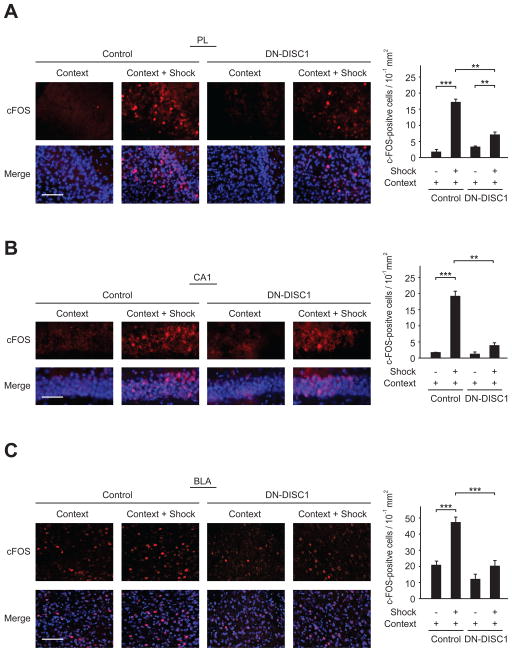

Alterations in neuronal activation via context-dependent fear memory retrieval in DN-DISC1 mice

The expression of c-Fos, an immediate early gene, has been used extensively as a marker for neuronal activation induced by physiological stimuli, including contextual fear conditioning (Frankland et al., 2004; Lemos et al., 2010; Martel et al., 2012; Milanovic et al., 1998; Radulovic et al., 1998). Thus, we examined whether induction of c-Fos expression evoked by context-dependent memory retrieval is impaired in DN-DISC1 mice. When control mice that received a foot shock were re-exposed to the context, we found a marked increase of c-Fos-positive cells in the PL, CA1, and BLA, where c-Fos expression is elevated by contextual stimuli, as previously reported (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A, B, C) (Frankland et al., 2004; Lemos et al., 2010; Milanovic et al., 1998; Radulovic et al., 1998). Notably, reduction of elevation of c-Fos-positive cells induced by re-exposure to the context was observed in these brain regions in DN-DISC1 mice compared to those of control mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5A, B, C).

Fig. 5.

Impairment of contextual fear memory retrieval-mediated neuronal activation induced by DN-DISC1 expression. (A, B, C) Mice were subjected to contextual fear conditioning with or without a footshock (Shock), unconditional stimuli, and were euthanized 60 min after receiving conditional stimuli (Context), in the next day of fear conditioning. Brain sections were stained by anti-c-Fos antibody and the numbers of c-Fos-positive cells (red) in the prelimbic area of the PFC (PL), CA1 region of the HPC (CA1), and basolateral amygdala (BLA) were counted in DN-DISC1 mice and wild type control mice. Memory retrieval induced by Context increased the number of c-Fos-positive cells in the PL compared to both wild type control and DN-DISC1 mice without Shock. In the CA1 region and BLA, the same effect was observed in control mice, whereas elevation of the number of c-Fos-positive cells did not reach statistical significance in DN-DISC1 mice. Memory retrieval-mediated elevation of c-Fos-positive cells of DN-DISC1 was significantly lower than that of wild type control mice in these brain regions. Blue, nucleus. Scale bar, 100 μm (A), 50 μm (B), 100 μm (C). Bars represent averages of each group in three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 determined by two-way ANOVA with posthoc test. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

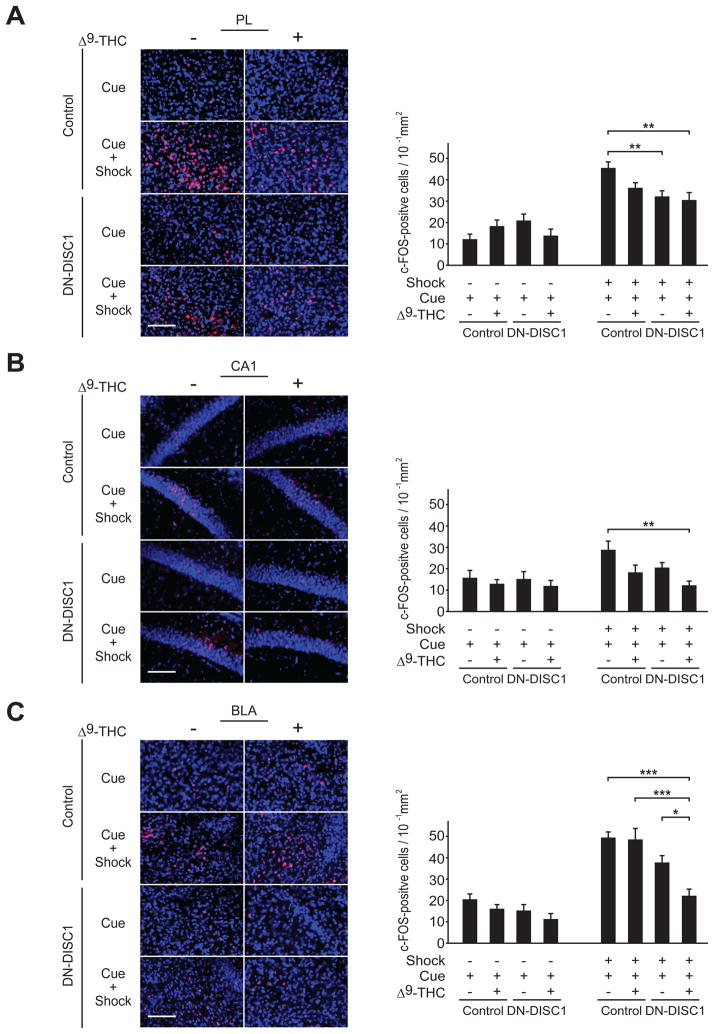

Alterations in neuronal activation via cue-dependent fear memory retrieval in DN-DISC1 mice

We next examined the effect of DN-DISC1 expression and adolescent Δ9-THC exposure on c-Fos expression evoked by cue-dependent memory retrieval. While DN-DISC1 expression suppressed an increase of c-Fos positive cells in the PL induced by re-exposure to the cue (P < 0.01), Δ9-THC treatment has no additional suppressive effect on c-Fos activation (Fig. 6A). We also found that either Δ9-THC treatment or DN-DISC1 expression evokes a slight reduction of c-Fos elevation in the CA1. The effect of Δ9-THC was exacerbated in DN-DISC1 mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). In the BLA, although Δ9-THC treatment has no effect on c-Fos elevation induced by re-exposure to the cue in control mice compared to vehicle-treated mice, Δ9-THC treatment had an exacerbating effect on suppression of c-Fos elevation induced by DN-DISC1 expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Exacerbating effect of adolescent Δ9-THC treatment on impaired cued fear memory retrieval-mediated neuronal activation induced by DN-DISC1 expression. (A, B, C) Mice were subjected to cued fear conditioning with or without a footshock (Shock), and were euthanized 90 min after receiving conditional stimuli (Cue) in the next day of fear conditioning. Brain sections were stained by anti-c-Fos antibody and the numbers of c-Fos-positive cells (red) in the prelimbic area of the PFC (PL), CA1 region of the hippocampus (CA1), and basolateral amygdala (BLA) were counted in DN-DISC1 mice and wild type control mice. In the PL, an increase of c-Fos positive cells induced by re-exposure to the cue was suppressed by DN-DISC1 expression, whereas Δ9-THC treatment has no additional suppressive effect on c-Fos activation. In the CA1, either Δ9-THC treatment or DN-DISC1 expression induces slight trend of reduction of c-Fos elevation by re-exposure to the cue. Suppression of c-Fos elevation caused by Δ9-THC was exacerbated by DN-DISC1 expression. In the BLA, no changes in c-Fos elevation were observed in wild type mice treated with Δ9-THC, compared to the vehicle-treated ones. The expression of DN-DISC1 induces slight trend of reduced c-Fos elevation by re-exposure to the cue, which was exacerbated by Δ9-THC treatment. Blue, nucleus. Scale bar, 100 μm (A), 50 μm (B), 100 μm (C). Bars represent averages of each group in three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 determined by two-way ANOVA with posthoc test. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating synergistic detrimental effects of adolescent cannabis exposure and a predisposing putative DISC1 mutation on cognitive and emotional behaviors. Interestingly, detrimental effects of adolescent cannabis exposure on cognitive behaviors have been reported in mouse models of other genetic risk factors for psychiatric conditions, such as COMT and neuregulin 1 (Long et al., 2013; O’Tuathaigh et al., 2010). In addition, mouse models with a genetic deletion of St8SIA2 exposed to juvenile Δ9-THC treatment displayed a synergistic impairment in learning and memory tasks (Tantra et al., 2014). Thus, cannabis exposure during development in animal models of genetic insults associated with psychiatric conditions is a useful strategy to explore gene-environmental interaction.

We report that chronic treatment with Δ9-THC during adolescence exacerbates deficits in adult cue-dependent fear memory in DN-DISC1 mice. Deficits in contextual fear memory were also observed in DN-DISC1 mice without adolescent exposure to Δ9-THC. In order to determine whether adolescence is particularly vulnerable to cannabis exposure, it would be of interest to test potential effects of adult Δ9-THC treatment on fear-associated memory in DN-DISC1 mice. Emotional dysfunction has been considered a hallmark of schizophrenia dating back to early days of research. Emotional disturbances in brain circuits, especially the amygdala, plays a key part in symptoms of schizophrenia (Aleman and Kahn, 2005). Many studies demonstrate a lack of activation of the amygdala during exposure to fearful or aversive stimuli, or after priming for negative affect in comparison to controls (Aleman and Kahn, 2005). Further research has shown a lack of recruitment of amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex response to threatening faces when compared to controls, as measured by fMRI (Satterthwaite et al., 2010). These findings suggest dysfunctional processing of threat-related signals in the environment may exacerbate impairments in emotional cognition in schizophrenia.

We demonstrated no effect of chronic adolescent Δ9-THC exposure on object recognition memory in adulthood in control mice. Interestingly, different outcomes in these cognitive aspects have been reported by acute and chronic treatment with not only Δ9-THC, but also other cannabinoid receptor agonists, such as Win55-212-2 and HU-210 (Zanettini et al., 2011). This may result from different experimental designs, such as dose and timing of pharmacological administration with drugs that have different binding affinity and efficacy at cannabinoid receptors (Felder et al., 1995). Notably, in the present study, animals had a washout period after chronic Δ9-THC administration, which allowed us to exclude direct acute effects of Δ9-THC on adult neuronal functions. A washout period is critical for examining long lasting effects of Δ9-THC treatment in adulthood, which causes alterations in neuronal circuit maturation during adolescence. In this study, we measured novel object recognition after a 24 hour delay. It should be considered that different outcomes could result from shorter or longer delays between phases 1 and 2 in the novel object exploration test. Although multiple psychological domains are impaired in mental disorders, memory function is in particular interesting to specifically test the gene and environment interaction, as many studies report deficits in memory function in cannabis users, as well as in patients with schizophrenia (Bossong et al., 2014; Gur and Gur, 2013; Kraguljac et al., 2013; Solowij and Michie, 2007; Wible, 2013).

A display of deficits in context-dependent fear memory, with no such deficits in other memory paradigms that are also HPC dependent, is curious. Previous studies exploring behavioral tasks associated with memory circuits influenced by the HPC have also shown variation. For example, genetic deletion of Glutamate delta-1 causes reduced expression of hippocampal glutamate receptors and disruption in contextual fear conditioning, yet not in spontaneous alternations during Y-Maze task nor in novel object recognition tasks (Yadav et al., 2013). Thus, hippocampal memory circuitry varies depending on the specific memory task (Jarrard, 1993; Warburton and Brown, 2015).

The effect of adolescent Δ9-THC exposure and DN-DISC1 expression on the endocannabinoid system was demonstrated by showing a reduction of synaptic CB1R expression in the PFC, HPC, and AMG. We also observed that neuronal activation induced by fear memory retrieval is impaired in DN-DISC1 mice. How does Δ9-THC treatment and DN-DISC1 alter synaptic CB1R expression? Is altered synaptic expression of CB1R caused by DN-DISC1 involved in impaired fear-associated memory? There has been substantial progress in understanding the mechanisms of the CB1R-mediated endocannabinoid system in brain development and its role for regulating synaptic plasticity (Harkany et al., 2007; Heifets and Castillo, 2009; Kano et al., 2009; Katona and Freund, 2012). Thus, these questions deserve to be investigated in future studies.

Conclusions

Our study further supports the idea that adolescent cannabis use is an environmental risk to exacerbate cognitive and emotional behavioral abnormalities in individuals with genetic vulnerabilities. As previously mentioned, prior studies demonstrated synergistic effects of DN-DISC1 and other environmental stimuli (Abazyan et al., 2014; Ibi et al., 2010; Niwa et al., 2013), suggesting that the DN-DISC1 mouse model is a useful tool to investigate how genetic insults and environmental risks interact to affect brain development and contribute to cognitive and emotional phenotypes. Thus, despite the etiological complexities of psychiatric conditions, the effect of adolescent cannabis exposure on the convergent mechanisms of the endocannabinoid system and DISC1 warrants further investigation as a model of gene-environment interaction, which may provide us with clues to identify novel drug targets for therapeutic intervention of these devastating conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Pamela Talalay and Koko Ishizuka for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Dean Wong for advice on project planning. This work was supported by R01MH-091230 (A.K.), P50MH-094268 (A.K., A.S., M.P.), R21AT008547 (A.K.), R01DA011322 (K.M.), and K05DA021696 (K.M.).

References

- Abazyan B, et al. Chronic exposure of mutant DISC1 mice to lead produces sex-dependent abnormalities consistent with schizophrenia and related mental disorders: a gene-environment interaction study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:575–84. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman A, Kahn RS. Strange feelings: do amygdala abnormalities dysregulate the emotional brain in schizophrenia? Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:283–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson S, et al. Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet. 1987;2:1483–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, et al. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325:1212–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossong MG, et al. Acute and non-acute effects of cannabis on human memory function: a critical review of neuroimaging studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2114–25. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossong MG, Niesink RJ. Adolescent brain maturation, the endogenous cannabinoid system and the neurobiology of cannabis-induced schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:370–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon NJ, Sawa A. Linking neurodevelopmental and synaptic theories of mental illness through DISC1. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:707–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:583–90. doi: 10.1038/nrn1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Forti M, et al. High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:488–91. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1 receptor-dependent trafficking of striatal NMDA glutamate receptors to the postsynaptic membrane. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5546–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, et al. Development of cannabinoid 1 receptor protein and messenger RNA in monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;20:1164–74. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, et al. Comparison of the pharmacology and signal transduction of the human cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, et al. The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in remote contextual fear memory. Science. 2004;304:881–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1094804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin BJK, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, et al. Prefrontal cortical regulation of fear learning. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason KA, et al. Susceptibility of the adolescent brain to cannabinoids: long-term hippocampal effects and relevance to schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e199. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Gur RE. Memory in health and in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:399–410. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/rgur. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, et al. The emerging functions of endocannabinoid signaling during CNS development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifets BD, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid signaling and long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:283–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquet C, et al. Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people. BMJ. 2005;330:11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikida T, et al. Dominant-negative DISC1 transgenic mice display schizophrenia-associated phenotypes detected by measures translatable to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibi D, et al. Combined effect of neonatal immune activation and mutant DISC1 on phenotypic changes in adulthood. Behav Brain Res. 2010;206:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:187–93. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro-Peled H, et al. Neurodevelopmental mechanisms of schizophrenia: understanding disturbed postnatal brain maturation through neuregulin-1-ErbB4 and DISC1. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:485–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro-Peled H, et al. Subcortical dopaminergic deficits in a DISC1 mutant model: a study in direct reference to human molecular brain imaging. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1574–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrard LE. On the role of the hippocampus in learning and memory in the rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1993;60:9–26. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AW, et al. Cognitive and motivational deficits together with prefrontal oxidative stress in a mouse model for neuropsychiatric illness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12462–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307925110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2013: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, et al. DISC1 Pathway in Brain Development: Exploring Therapeutic Targets for Major Psychiatric Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:25. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, et al. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:309–80. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Freund TF. Multiple Functions of Endocannabinoid Signaling in the Brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012 doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraguljac NV, et al. Memory deficits in schizophrenia: a selective review of functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) studies. Behav Sci (Basel) 2013;3:330–47. doi: 10.3390/bs3030330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, Grace AA. The roles of cannabinoid and dopamine receptor systems in neural emotional learning circuits: implications for schizophrenia and addiction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1597–613. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson VC, et al. The effect of cannabis use and cognitive reserve on age at onset and psychosis outcomes in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:873–80. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JI, et al. Involvement of the prelimbic prefrontal cortex on cannabidiol-induced attenuation of contextual conditioned fear in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long LE, et al. Transmembrane domain Nrg1 mutant mice show altered susceptibility to the neurobehavioural actions of repeated THC exposure in adolescence. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:163–75. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek R, et al. The amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex: partners in the fear circuit. J Physiol. 2013;591:2381–91. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system controls extinction of aversive memories. Nature. 2002;418:530–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel G, et al. Murine GRPR and stathmin control in opposite directions both cued fear extinction and neural activities of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettunen J, et al. Association of cannabis use with prodromal symptoms of psychosis in adolescence. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:470–1. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic S, et al. Production of the Fos protein after contextual fear conditioning of C57BL/6N mice. Brain Res. 1998;784:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, et al. Adolescent stress-induced epigenetic control of dopaminergic neurons via glucocorticoids. Science. 2013;339:335–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1226931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, et al. Knockdown of DISC1 by in utero gene transfer disturbs postnatal dopaminergic maturation in the frontal cortex and leads to adult behavioral deficits. Neuron. 2010;65:480–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Tuathaigh CM, et al. Chronic adolescent exposure to Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in COMT mutant mice: impact on psychosis-related and other phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2262–73. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic J, et al. Relationship between fos production and classical fear conditioning: effects of novelty, latent inhibition, and unconditioned stimulus preexposure. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7452–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Parolaro D. Long lasting consequences of cannabis exposure in adolescence. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:S108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehle S, et al. The endocannabinoid system in anxiety, fear memory and habituation. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:23–39. doi: 10.1177/0269881111408958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, et al. Endocannabinoid system: potential novel targets for treatment of schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;53:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite TD, et al. Association of enhanced limbic response to threat with decreased cortical facial recognition memory response in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:418–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowij N, Michie PT. Cannabis and cognitive dysfunction: parallels with endophenotypes of schizophrenia? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:30–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H, et al. The role of cannabinoid transmission in emotional memory formation: implications for addiction and schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:73. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantra M, et al. St8sia2 deficiency plus juvenile cannabis exposure in mice synergistically affect higher cognition in adulthood. Behav Brain Res. 2014;275:166–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronson NC, et al. Fear conditioning and extinction: emotional states encoded by distinct signaling pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K, et al. Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;83:393–411. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, et al. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:319–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Brown MW. Neural circuitry for rat recognition memory. Behav Brain Res. 2015;285:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wible CG. Hippocampal physiology, structure and function and the neuroscience of schizophrenia: a unified account of declarative memory deficits, working memory deficits and schizophrenic symptoms. Behav Sci (Basel) 2013;3:298–315. doi: 10.3390/bs3020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R, et al. Deletion of glutamate delta-1 receptor in mouse leads to enhanced working memory and deficit in fear conditioning. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanettini C, et al. Effects of endocannabinoid system modulation on cognitive and emotional behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:57. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoubovsky SP, et al. Working memory deficits in neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice: potential impairments in prefrontal cortex mediated cognitive function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408:707–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]