Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate PSA levels and kinetic cutoffs to predict positive bone scans for men with non-metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) cohort.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 531 bone scans of 312 clinically CRPC patients with no known metastases at baseline treated with a variety of primary treatment types in the SEARCH database. The association of patients’ demographics, pathological features, PSA levels and kinetics with risk of a positive scan was tested using generalized estimating equations.

Results

A total of 149 (28%) scans were positive. Positive scans were associated with younger age (OR=0.98; P=0.014), higher Gleason scores (relative to Gleason 2-6, Gleason 3+4: OR=2.03, P=0.035; Gleason 4+3 and 8-10: OR=1.76, P=0.059), higher pre-scan PSA (OR=2.11; P<0.001), shorter pre-scan PSA doubling time (PSADT; OR=0.53; P<0.001), higher PSA velocity (OR=1.74; P<0.001) and more remote scan year (OR=0.92; P=0.004). Scan positivity was 6%, 14%, 29% and 57% for men with PSA <5, 5-14.9, 15-49.9 and ≥50ng/mL, respectively (P-trend <0.001). Men with PSADT ≥15, 9-14.9, 3-8.9 and <3 months had a scan positivity of 11%, 22%, 34% and 47%, correspondingly (P-trend <0.001). Tables were constructed using PSA and PSADT to predict the likelihood of a positive bone scan.

Conclusions

PSA levels and kinetics were associated with positive bone scans. We developed tables to predict the risk of positive bone scans by PSA and PSADT. Combining PSA levels and kinetics may help select patients with CRPC for bone scans.

Keywords: Disease-Free Survival, Metastasis, Mortality, Prostate Cancer, Prostatectomy, Prostate Specific Antigen

Introduction

With the recent advances in hormonal-, chemo-, and immunotherapies for metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), early detection of metastasis has become more and more important as these patients may benefit from early interventions.1-3 For example, asymptomatic patients with metastatic CRPC have been shown to benefit from new therapies such as sipuleucel-T,4 abiraterone,5 and enzalutamide.6 Given these treatments have been shown to benefit CRPC patients with metastasis before the development of symptoms, a strategy to detect metastases early, when symptoms are still absent, is crucial. Bone scans are routinely used to detect bone metastasis in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients; however, to date it remains unclear when screening for metastasis should start, how often bone scans should be performed and whether the scans should be done at regular time intervals or triggered by changes in clinical and/or biochemical variables.7-10 In a previous study, we showed, among prostate cancer (PCa) patients with rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) after radical prostatectomy, PSA levels and PSA kinetics (such as PSA doubling time [PSADT] and PSA velocity [PSAV]) were predictive of metastatic disease.11 However, there are limited studies evaluating how PSA levels and PSA kinetics can be used alone or in concert to estimate the risk of a positive scan specifically among CRPC patients. Therefore, we examined PSA levels and PSA kinetic cutoffs to predict a positive bone scan among men with CRPC within the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) cohort.

Methods

Study population

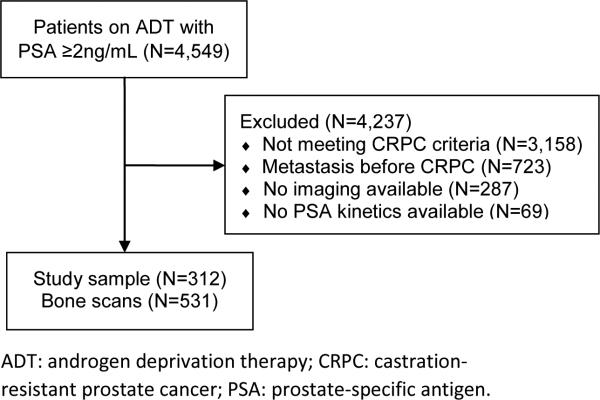

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, data from PCa patients treated at two Veteran Affairs Medical Centers (San Diego, CA and Durham, NC) with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) between 1991 and 2013 with PSA levels ≥2ng/mL after starting ADT were combined into the study database.12 The database included information on patient age at time of bone scan, race, height, weight, PSA, biopsy tumor grade, bone scans and primary and secondary treatments for PCa. A total of 4,549 subjects on ADT for PCa with PSA levels ≥2ng/mL after ADT were entered in the database. Of these, 1,391 (31%) had documented CRPC as defined by the PCa working group 2 definition: a 25% or greater increase in PSA and an absolute increase of 2ng/mL or more from the post-ADT nadir while receiving continuous ADT (either gonadotropin-release hormone agonist, antagonist or bilateral orchiectomy).13 As our goal was to study men with no known metastases, 723 (52%) men who had documented metastatic disease at or before the time of CRPC diagnosis were excluded. Of the remaining 668 patients, a total of 381 (57%) had one or more bone scans available for review and were included in the study. Patients without data on PSA levels and/or kinetics (namely PSADT and PSAV) were excluded, resulting in a final study sample of 312 (82%) patients (Figure 1). Among these patients, a total of 531 bone scans were reviewed and included in the study. Bone scans performed after the first positive scan were not included. Supplemental figure S1 shows the number of scans per patient. The number and interval of bone scans, primary and secondary treatments for PCa were at the discretion of the patient and treating physician. Bone scans were read by nuclear medicine radiologists. Radiologists were not blinded to patient's demographics, laboratory, radiologic or pathologic results. Bone scans were coded by trained personnel as positive or negative based upon the radiology report (equivocal scans, given they usually do not prompt a change in management, were considered negative unless confirmed positive by a secondary imaging modality or biopsy).

Figure 1.

Diagram of study sample

Statistical analysis

PSADT was calculated by the natural log of two divided by the slope of the linear regression of the natural log of PSA over time in months.14 Subjects with calculated PSADT <0 or >120 were assigned 120 months for ease of analysis. PSAV was calculated as the slope of the linear regression of PSA over time in years. All available PSA levels prior to the bone scan but after CRPC diagnosis were used to calculate pre-scan PSA kinetics. Subjects with ≥2 PSA values over at least three months had PSA kinetics calculated. Results are presented in counts and percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. The unity of measure in the study was bone scan, as opposed to patients. Given the repeated measures nature of the data, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to compare patients’ demographics, pathological features, PSA levels and kinetics between negative and positive scans, grouping by patient. The variables analyzed included: age at CRPC (years), self-identified race (black or non-black), biopsy Gleason score (<=6, 3+4 or 4+3 and 8-10)15, primary treatment (watchful waiting or ADT, radical prostatectomy ± radiation, radiation alone, other), time from ADT to CRPC (months), PSA at CRPC (log[ng/mL]), time from CRPC to scan (months), number of previous post-CRPC negative bone scans (0, 1, 2, ≥3), time from previous scan (in months), pre-scan PSA (log[ng/mL]), pre-scan PSADT (log[months]), pre-scan PSAV (log [ng/ml/year]) and year of scan. Multivariable analyses were also performed using GEE and included all covariates above, given they were associated with metastasis in present study or previously. As PSAV and PSADT were collinear, only PSADT was included in the multivariable model. PSA levels were then broken down into four groups based on quartiles: 0.0-4.9, 5.0-14.9, 15.0-49.9 and ≥50.0ng/mL. Similarly, PSADT was divided into four groups: ≥15, 8.9-14.9, 3.0-8.9 and <3 months based upon a prior paper showing these cut-points risk stratified patients for PCa death, albeit in men with castrate-sensitive disease.16 Bar plots were used to demonstrate the relative prevalence of positive bone scans by PSA and PSADT groups. A table of point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for probability of bone scan positivity by PSA and PSADT groups was estimated from the GEE including PSA levels and PSADT as categorical variables. The area under the curve (AUC) of the predicted risk by the table and scan positivity was calculated. All statistical analyses were two-tailed and performed using Stata 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R 3.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The median (IQR) age at bone scan of our sample was 74 years (66-81). A total of 172 (37%) scans were done in black patients. The median (IQR) PSA at CRPC diagnosis and pre-scan PSA were, respectively, 3.9 (2.8-7.5) and 17.1ng/mL (6.5-52.5). The median (IQR) pre-scan PSADT and pre-scan PSAV were 11.4 months (5.0-26.7) and 6.8ng/mL/year (1.6-25.7), correspondingly. At diagnosis, low (<=6), intermediate (3+4), high-grade (4+3 and 8-10) and unknown Gleason scores were present in 93 (18%), 88 (17%), 178 (34%) and 172 scans (32%), respectively. The median (IQR) time from ADT to CRPC and CRPC to bone scan were 44 (24-73) and 20 months (11-35), correspondingly. The primary PCa treatment was watchful waiting or ADT in 216 (41%) scans, radical prostatectomy ± radiation in 138 (26%) scans, radiation alone in 166 (32%) and other in 3 (1%) scans (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics by bone scan positivity

| Variables | Positive bone scan | Negative bone scan | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Number of scans, N (%) | 149 (29) | 382 (72) | - | - | - | - |

| Age at CRPC (years), median (Q1, Q3) | 72 (65, 78) | 75 (66, 82) | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 0.014 | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) | 0.096 |

| Race, N (%) | ||||||

| Non-black | 97 (65) | 262 (69) | ref. | - | ref. | - |

| Black | 52 (35) | 120 (31) | 1.17 (0.80-1.72) | 0.428 | 0.84 (0.51-1.38) | 0.492 |

| Biopsy Gleason score, N (%) | ||||||

| <=6 | 19 (13) | 74 (19) | ref. | - | ref. | - |

| 3+4 | 30 (20) | 58 (15) | 2.03 (1.07-3.86) | 0.035 | 2.86 (1.28-6.38) | 0.010 |

| 4+3, 8-10 | 55 (37) | 123 (32) | 1.76 (0.98-3.16) | 0.059 | 1.51 (0.74-3.08) | 0.257 |

| Unknown | 45 (30) | 127 (33) | 1.37 (0.74-2.51) | 0.305 | 1.46 (0.71-3.00) | 0.299 |

| Primary treatment, N (%) | ||||||

| Watchful Waiting or ADT | 61 (41) | 155 (41) | ref. | - | ref. | - |

| Radical Prostatectomy ± Radiation | 42 (28) | 96 (25) | 1.11 (0.70-1.76) | 0.658 | 0.47 (0.12-1.79) | 0.269 |

| Radiation Alone | 44 (30) | 122 (32) | 0.90 (0.58-1.41) | 0.649 | 0.54 (0.15-1.94) | 0.343 |

| Other | 2 (1) | 9 (2) | 0.57 (0.14-2.34) | 0.470 | 0.46 (0.13-1.65) | 0.231 |

| Time from ADT to CRPC (months), median (Q1, Q3) | 46 (21, 73) | 43 (26, 74) | 1.09 (0.88-1.35) | 0.471 | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 0.104 |

| PSA at CRPC (ng/mL), median (Q1, Q3)‡ | 3.8 (2.8, 7.5) | 3.9 (2.7, 7.5) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 0.127 | ¥ | - |

| Time from CRPC to scan (months), median (Q1, Q3) | 19 (12, 34) | 20 (10, 35) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.780 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.355 |

| # Previous post-CRPC negative bone scans, N (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 78 (52) | 234 (61) | ref. | - | ref. | - |

| 1 | 44 (30) | 95 (25) | 1.84 (1.25-2.71) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.60-2.14) | 0.687 |

| 2 | 12 (8) | 35 (9) | 1.76 (0.96-3.21) | 0.067 | 0.82 (0.30-2.23) | 0.700 |

| ≥3 | 15 (10) | 18 (5) | 5.43 (2.60-11.37) | <0.001 | 1.38 (0.39-4.81) | 0.616 |

| Time from previous scan (months), median (Q1, Q3) | 12 (7, 12) | 12 (7, 12) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.538 | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.989 |

| Pre-scan PSA (ng/mL), median (Q1, Q3) ‡ | 55.5 (25.7, 144.1) | 12.9 (5.3, 31.4) | 2.11 (1.77-2.53) | <0.001 | 1.85 (1.50-2.30) | <0.001 |

| Pre-scan PSADT (months), median (Q1, Q3) ‡ | 5.4 (2.9, 10.7) | 9.1 (3.0, 18.2) | 0.53 (0.44-0.64) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.55-0.98) | 0.035 |

| Pre-scan PSAV (ng/mL/year), median (Q1, Q3) | 24.8 (8.8, 83.5) | 4.3 (0.8, 13.9) | 1.74 (1.49-2.04) | <0.001 | ¥ | - |

| Year of scan, median (Q1, Q3) | 2007 (2004, 2010) | 2008 (2005, 2011) | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | 0.004 | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) | 0.056 |

ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy; BCR: biochemical recurrence; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; PSADT: PSA doubling time; PSAV: PSA velocity; ref: reference group; Q1: 25th percentile; Q3: 75th percentile.

Log-transformed variable was used in this analysis.

indicates the variable was excluded from the multivariable model due to collinearity

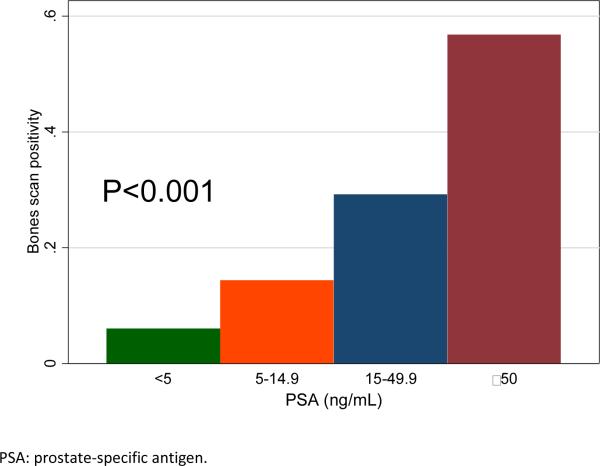

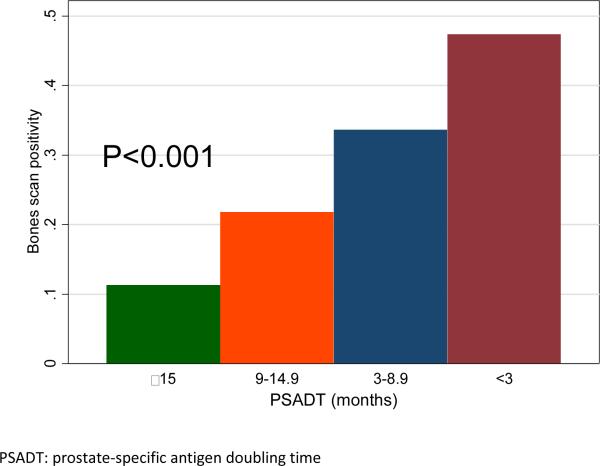

The average number of scans per patient was 1.7. A total of 149 (28%) scans were positive for metastatic disease. In univariable analysis, positive bone scan was significantly associated with younger age (OR=0.98, P=0.014), higher pre-scan PSA levels (OR=2.11, P<0.001), shorter pre-scan PSADT (OR=0.53, P<0.001), higher PSAV (OR=1.74, P<0.001) and more remote year of scan (OR=0.92, P=0.004). Bone scan positivity was unrelated to race, PSA level at CRPC diagnosis, time from previous scan, time from ADT to CRPC and time from CRPC to bone scan (all P>0.05, Table 1). Patients with higher Gleason scores had a higher risk of having a positive scan (relative to Gleason <=6, Gleason 3+4: OR=2.03, P=0.035; Gleason 4+3 and 8-10: OR=1.76, P=0.059). Greater number of prior negative scans was associated with higher scan positivity (relative to no prior scans, 1 scan: OR=1.84, P=0.002; 2 scans OR=1.76, P=0.067; 3 or more scans: OR=5.43, P=<0.001). In multivariable analysis, only pre-PSA (OR=1.87, P=<0.001) and pre-PSADT (OR=0.73, P=0.035) were independently associated with bone scan positivity (Figure 1). In the analysis by PSA groups, the scan positivity was 6%, 14%, 29% and 57% for men with PSA <5, 5-14.9, 15-49.9 and ≥50ng/mL, respectively (P-trend <0.001; Figure 2). Men with PSADT ≥15, 9-14.9, 3-8.9 and <3 months had a scan positivity of 11%, 22%, 34% and 47%, correspondingly (P-trend <0.001; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Bone scan positivity by pre-scan PSA groups

Figure 3.

Bone scan positivity by pre-scan PSADT groups

Given pre-scan PSA and PSA kinetics were the only two independent predictors of bone scan positivity, we developed a table estimating bone scan positivity by pre-scan PSA levels and pre-scan PSADT (Table 2). In subjects with PSADT ≥15 months and PSA levels <5ng/mL the estimated bone scan positivity was only 6% (95% confidence interval [CI]=4-8%) compared to 67% (95% CI=64-69%) among patients with PSADT <3 months and PSA levels ≥50ng/mL. The accuracy (AUC) of the table to predict a positive scan was 77.3%.

Table 2.

Predicted risk of positive scan by PSA and PSADT groups

| PSA (ng/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSADT (months) | <5 | 5-14.9 | 15-49.9 | ≥50 |

| ≥15 | 6 (4-8) | 11 (9-14) | 22 (18-28) | 47 (40-54) |

| 9-14.9 | 6 (4-10) | 12 (10-14) | 24 (22-26) | 49 (46-52) |

| 3-8.9 | 8 (5-14) | 16 (13-18) | 30 (27-33) | 57 (53-60) |

| <3 | 12 (8-19) | 22 (19-25) | 40 (37-42) | 67 (64-69) |

Cells represent the average estimate (95% confidence intervals in parenthesis)

Discussion

For non-metastatic CRPC patients, the recently published American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines recommend observation with continued ADT.17 Chemo- or immunotherapy are contraindicated for these patients outside of a clinical trial context. However, for patients with asymptomatic metastatic CRPC, the AUA guidelines recommend active treatment with abiraterone plus prednisone, docetaxel or sipuleucel-T.17 Moreover, there is evidence to suggest early treatment translates into better response to sipuleucel-T2 and docetaxel.3 Thus, as earlier treatment of metastatic CRPC may lead to better outcomes, it is critical to identify metastasis as early as possible. In order to identify CRPC patients at risk for metastatic disease early, we evaluated the predictors of a positive bone scan among men with non-metastatic CRPC. We found positive bone scans were most strongly associated with higher PSA levels and adverse PSA kinetics (shorter PSADT and faster PSAV). Thus, we combined PSA and PSADT to create a table stratifying CRPC patients according to the risk of having a positive bone scan. This table may help physicians select patients for metastatic screening with bone scans. It may also help select patients for clinical trials based on bone metastasis risk.

In our previous study evaluating PCa patients with rising PSA after radical prostatectomy, we found PSA levels and PSA kinetics were associated with the risk of metastatic disease.11 Likewise, in the current study we found higher PSA levels and adverse PSA kinetics were associated with a greater chance the bone scan would show metastatic disease. Secondary analysis of clinical trials evaluating time from CRPC to metastasis also came to the same conclusions that PSA variables correlate with risk of future metastasis.18-20 For example, Smith et al, in a secondary analysis of 201 patients in an aborted clinical trial, found a three-fold increase in the hazards of metastatic disease for each 10ng/mL increase in PSA levels. They also found a 40% increase in the hazards of metastatic disease for each one-unit increase in the log of PSA velocity.18 In another study, Smith et al, found a two-fold increase in the hazards of metastatic disease when the PSA level was above 13 compared to less than 13 ng/mL.19 In both of these studies, other variables associated with disease aggressiveness such as Gleason score were not consistently associated with the development of metastasis. In contrast to the clinical trials, our study reflects the clinical practice, not scans done per protocol. Moreover, the clinical trials only included men with negative baseline scans which is a selected group of men. Regardless of these differences, combined findings support the use of PSA levels and kinetics as the best currently available variables to stratify patients according to their risk of metastatic disease. Moreover, these variables may be used in concert to select patients for bone scans potentially reducing the number of negative scans.

To date, no studies evaluated the frequency of bone metastasis screening in patients with CRPC. Clinical trials evaluating medications to delay disease progression in patients with non-metastatic CRPC utilized bone scans every 2 to 4 months.18,19,21 In our study, the risk of a positive bone scan was correlated with PSA levels and PSA kinetics. For example, patients with PSA levels <5ng/mL and PSADT >15 months had less than a 10% chance of a positive scan while those with PSA levels ≥50 ng/mL and PSADT <3 months had greater than a 50% chance of being diagnosed with metastatic disease on a bone scan. These findings indicate the screening strategy for metastasis using bone scan should be tailored to the patient's characteristics such as PSA levels and kinetics, i.e. patients with higher PSA levels and shorter PSADTs should be screened more aggressively compared to those with lower PSA levels and/or longer PSADTs. However, based on the current data we are not able to determine the ideal time interval for bone scans or whether bone scans should be triggered by changes in PSA variables.

The main limitation of the present study is its retrospective nature. Prospective studies are required for level 1 evidence, such a study would be expensive and time consuming. In the absence of such data, retrospective studies can be useful for informing clinical practice until more definitive data are available. First, we were not able to control when and how bone scans were performed. It is plausible that patients with more advanced and aggressive disease at baseline had more and earlier bone scans compared to those with less advanced and aggressive disease for whom the bone scan may have been deferred to a later point in time. If this hypothesis is true, some patients with worse disease were more likely to be diagnosed with metastasis while a number of patients with more favorable disease may have been excluded from the study given they have never had a single bone scan. Likewise, we did not evaluate bone scans done outside the VA or scans done before CRPC diagnosis. Second, we had no control over when and how patients were treated with ADT and/or other therapies. Third, data on other variables such as bone health including alkaline phosphatase, bisphosphonates use was not available for most patients. Moreover, Gleason score was undetermined for a third of our sample and we had no data on lymph node status, extracapsular extension or seminal vesicle invasion (except for some of the patients who underwent radical prostatectomy). Data on testosterone levels and compliance with ADT was not systematically available for all patients. Additionally, close to 20% of our sample had missing PSA levels and/or kinetics and were excluded from the study. Fourth, the frequency of PSA measurements was at the discretion of the treating physician, which can lead to variations in how PSADT is calculated. Although these limitations add noise and unwanted variability to the study, they reflect the current clinical practice in the management of CRPC patients. Despite this limitation, PSADT was a very strong predictor of a positive scan suggesting that in an idealized setting, PSADT may be an even stronger predictor of bone scan results than observed in the current study. Fifth, our study encompassed more than two decades and we were unable to determine and account for temporal changes in clinical practice and technology. Finally, although bone scans are very sensitive to detect metastasis, false positives and negatives do occur, but we were unable to identify them given confirmatory imaging and/or biopsies were not available for all patients in our sample.

In conclusion, among non-metastatic CRPC patients undergoing bone scans for metastasis detection, PSA levels and PSA kinetics were the strongest predictors of positive bone scans. Based on this, we developed tables to predict the risk of a positive bone scan by PSA and PSADT. A combination of PSA levels and PSA kinetics may help select patients for bone scans potentially reducing the number of negative and unnecessary scans in low-risk men, while detecting metastatic disease at an earlier stage in high-risk men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research support: Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institute of Health R01CA100938 (WJA), NIH Specialized Programs of Research Excellence Grant P50 CA92131-01A1 (WJA), the Georgia Cancer Coalition (MKT), NIH K24 CA160653 (SJF) and Amgen.

This study was funded by Amgen and Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institute of Health R01CA100938 (WJA), NIH Specialized Programs of Research Excellence Grant P50 CA92131-01A1 (WJA), the Georgia Cancer Coalition (MKT), NIH K24 CA160653 (SJF).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Views and opinions of, and endorsements by the author(s) do not reflect those of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

Conflict of interest:

Disclosures:

Alexander Liede is employed by Amgen.

Supplementary information is available at Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases

References

- 1.Derleth CL, Yu EY. Targeted therapy in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncology. 2013;27(7):620–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schellhammer PF, Chodak G, Whitmore JB, Sims R, Frohlich MW, Kantoff PW. Lower baseline prostate-specific antigen is associated with a greater overall survival benefit from sipuleucel-T in the Immunotherapy for Prostate Adenocarcinoma Treatment (IMPACT) trial. Urology. 2013;81(6):1297–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelius T, Reiher F, Lindenmeir T, Klatte T, Rau O, Burandt J, et al. Characterization of prognostic factors and efficacy in a phase-II study with docetaxel and estramustine for advanced hormone refractory prostate cancer. Onkologie. 2005;28(11):573–578. doi: 10.1159/000088297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E, Autio K, Ryan CJ, Mulders P, Shore N, Kheoh T, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: patient-reported outcome results of a randomised phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology. 2013;14(12):1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):424–433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slovin SF, Wilton AS, Heller G, Scher HI. Time to detectable metastatic disease in patients with rising prostate-specific antigen values following surgery or radiation therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11(24 Pt 1):8669–8673. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okotie OT, Aronson WJ, Wieder JA, Liao Y, Dorey F, De KJ, et al. Predictors of metastatic disease in men with biochemical failure following radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2260–2264. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127734.01845.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dotan ZA, Bianco FJ, Jr., Rabbani F, Eastham JA, Fearn P, Scher HI, et al. Pattern of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) failure dictates the probability of a positive bone scan in patients with an increasing PSA after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1962–1968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeb S, Makarov DV, Schaeffer EM, Humphreys EB, Walsh PC. Prostate specific antigen at the initial diagnosis of metastasis to bone in patients after radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 2010;184(1):157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreira DM, Cooperberg MR, Howard LE, Aronson WJ, Kane CJ, Terris MK, et al. Predicting bone scan positivity after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy in both hormone-naive men and patients receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: results from the SEARCH database. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allott EH, Abern MR, Gerber L, Keto CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, et al. Metformin does not affect risk of biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2013;16(4):391–397. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1148–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton RJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Presti JC, Jr., Amling CL, et al. Limitations of prostate specific antigen doubling time following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. The Journal of urology. 2008;179(5):1785–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.040. discussion 1789-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright JL, Salinas CA, Lin DW, Kolb S, Koopmeiners J, Feng Z, et al. Prostate cancer specific mortality and Gleason 7 disease differences in prostate cancer outcomes between cases with Gleason 4 + 3 and Gleason 3 + 4 tumors in a population based cohort. The Journal of urology. 2009;182(6):2702–2707. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, et al. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294(4):433–439. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cookson MS, Roth BJ, Dahm P, Engstrom C, Freedland SJ, Hussain M, et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2013;190(2):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MR, Kabbinavar F, Saad F, Hussain A, Gittelman MC, Bilhartz DL, et al. Natural history of rising serum prostate-specific antigen in men with castrate nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2918–2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MR, Cook R, Lee KA, Nelson JB. Disease and host characteristics as predictors of time to first bone metastasis and death in men with progressive castration-resistant nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(10):2077–2085. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith MR, Saad F, Oudard S, Shore N, Fizazi K, Sieber P, et al. Denosumab and bone metastasis-free survival in men with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: exploratory analyses by baseline prostate-specific antigen doubling time. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(30):3800–3806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis NB, Ryan CW, Stadler WM, Vogelzang NJ. A phase II study of nilutamide in men with prostate cancer after the failure of flutamide or bicalutamide therapy. BJU international. 2005;96(6):787–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.