Abstract

Transcription factor CTIP2 (COUP-TF-interacting protein 2), also known as BCL11B, is expressed in hair follicles of embryonic and adult skin. Ctip2-null mice exhibit reduced hair follicle density during embryonic development. In contrast, conditional inactivation of Ctip2 in epidermis (Ctip2ep−/− mice) leads to a shorter telogen and premature entry into anagen during the second phase of hair cycling without a detectable change in the number of hair follicles. Keratinocytes of the bulge stem cells niche of Ctip2ep−/− mice proliferate more and undergo reduced apoptosis than the corresponding cells of wild-type mice. However, premature activation of follicular stem cells in mice lacking CTIP2 leads to the exhaustion of this stem cell compartment in comparison to Ctip2L2/L2 mice, which retained quiescent follicle stem cells. CTIP2 modulates expression of genes encoding EGFR and NOTCH1 during formation of hair follicles, and those encoding NFATC1 and LHX2 during normal hair cycling in adult skin. The expression of most of these genes is disrupted in mice lacking CTIP2 and these alterations may underlie the phenotype of Ctip2-null and Ctip2ep−/− mice. CTIP2 appears to serve as a transcriptional organizer that integrates input from multiple signaling cues during hair follicle morphogenesis and hair cycling.

Introduction

The hair follicle (HF) is a complex appendage of epidermis and its formation is regulated by epithelial-mesenchymal interaction (Botchkarev and Paus, 2003; Millar, 2002). Cross-talk between epithelium and mesenchyme initiates thickening of the epidermis to form the hair placode (Botchkarev and Paus, 2003; Millar, 2002), which gives rise to hair germ and then the bulbous hair peg(Paus et al., 1999). A mature HF consisting of the hair shaft, root sheaths and dermal papilla arise from the bulbous hair peg (Botchkarev and Paus, 2003; Millar, 2002; Paus et al., 1999). The mature HF undergoes cyclic changes of catagen (regression phase), telogen (quiescent phase), and anagen (active growth phase) (Muller Rover et al., 2001). Hair cycling homeostasis is maintained by a subset of multipotent, HF stem cells (HFSCs) residing in the bulge region of the HF (Tiede et al., 2007; Waters et al., 2007). HFSCs also have an important role in epidermal regeneration after injury (Ito et al., 2005).

Cell signaling pathways regulate every aspect of HF development and function. The WNT/β catenin, sonic hedgehog (SHH), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), NOTCH1, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathways regulate HF formation and cycling (Andl et al., 2002; Botchkarev et al., 1999; Chiang et al., 1999; Crowe et al., 1998; Crowe and Niswander, 1998; Doma et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 1997; Huelsken et al., 2001; Lee and Tumbar, 2012; Lin et al., 2011; Lyons et al., 1990; Murillas et al., 1995; Nakamura et al., 2013; St Jacques et al., 1998; Uyttendaele et al., 2004; Vauclair et al., 2005).

Bulge SC activation and homeostasis is regulated by the β catenin/TCF/LEF1 pathway and downstream proteins (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Merrill et al., 2001; Nguyen et al., 2006). LIM Homeobox 2 (LHX2) is an important factor in follicular organogenesis and cycling (Rhee et al., 2006; Tornqvist et al., 2010), whereas NFATC1 and SOX9 regulate HFSCs during hair cycling in the adult (Gafter-Gvili et al., 2003; Horsley et al., 2008; Vidal et al., 2005).

The transcriptional regulator CTIP2 is a C2H2 zinc finger protein (Avram et al., 2000; Avram et al., 2002) that is highly expressed in neonatal and adult skin and plays a significant role in murine skin morphogenesis and homeostasis (Golonzhka et al., 2007). Germline deletion of Ctip2 in mice leads to impaired epidermal proliferation, differentiation, and delayed EPB formation (Golonzhka et al., 2009). Epidermal-specific ablation of Ctip2 triggers atopic dermatitis-like skin inflammation with concurrent infiltration of T lymphocytes, mast cells and eosinophils in adult mice (Wang et al., 2012).

CTIP2 is expressed in both developing and adult HFs (Golonzhka et al., 2007). It is co-expressed with SC markers, such as K15 and CD34, in HF bulge region (Golonzhka et al., 2007). Ablation of Ctip2 in the epidermis delays wound healing and induces abnormal expression of HFSC markers (Liang et al., 2012). However, CTIP2 expression during postnatal follicle establishment and cycling has not been studied extensively and it is also unknown whether CTIP2 controls HFSCs during embryonic follicle development and/or hair cycling. We observed that CTIP2 has a distinct pattern of expression during follicular maturation and cycling. Moreover, CTIP2 regulates HF formation and control NOTCH1 and EGFR signaling pathways during embryonic HF development. In this study, we have also demonstrated that CTIP2 plays a critical role in maintaining the bulge SC reservoir and directly regulates NFATC1 and LHX2 expression during postnatal hair cycling. Our results establish CTIP2 as a top-level regulator of hair follicle morphogenesis and cycling.

Results

Impaired HF morphogenesis and dysregulated expression of key players of HF morphogenesis in Ctip2-null mice

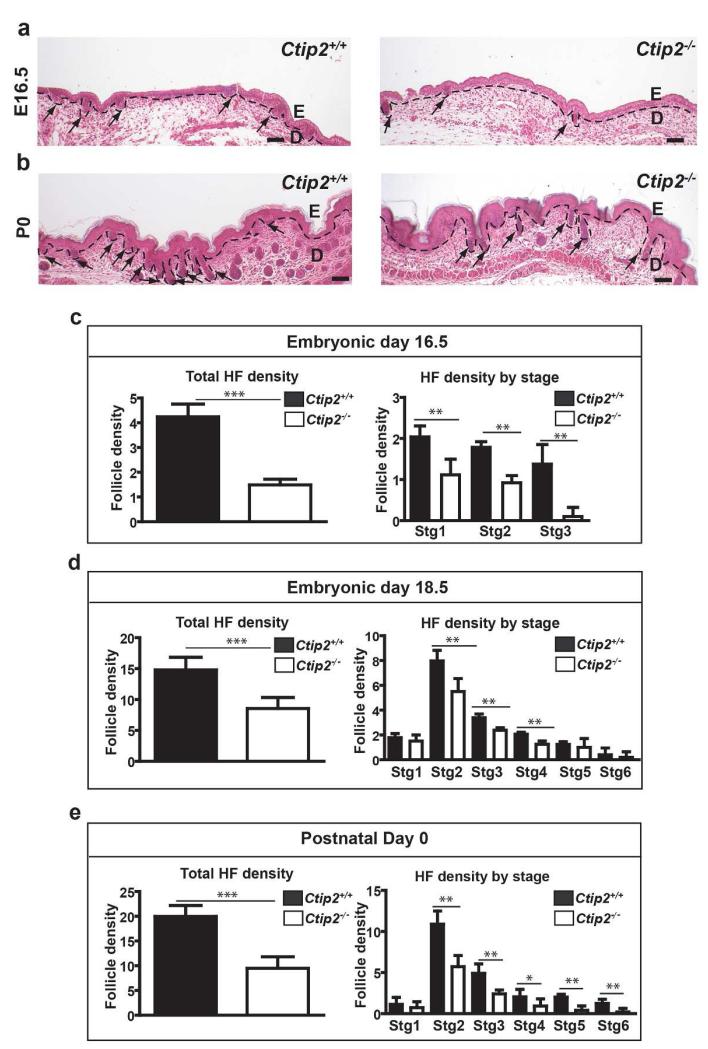

HF progenitors proceed through eight stages of development that are distinguished by basal to apical length (Paus et al., 1999). CTIP2 is expressed in all stages of HF morphogenesis (Golonzhka et al., 2007). In order to elucidate the role of CTIP2 in HF morphogenesis, we quantified HFs in wild-type and Ctip2-null skin from E14.5 to P0. The number of HFs in the mutant skin was indistinguishable from that of wild-type mice at E14.5 (Figure S1a and S1b). In contrast, HFs was less abundant in Ctip2-null skin from E16.5 through P0 (Figure 1a and 1b). Dorsal skin of E16.5 Ctip2−/− embryos also produced fewer hair follicles in stages 1 – 3 (Figure 1c). The reduction in HF density in the mutants was more striking at E18.5 and P0 (Figures 1d and e), when Ctip2−/− skin displayed fewer HFs at Stages 2-4 (Figure 1d and e). Ctip2−/− mice exhibited a reduced number of HFs in Stage 5 and Stage 6 at P0 (Figure 1e). Unlike the abnormality in hair follicle numbers, hair follicles structure was unaltered in Ctip2−/− skin. These results suggest that CTIP2 plays an important role in morphogenesis of the HF during skin development.

Figure 1. Impaired HF formation in Ctip2-null mice during development.

(a-b) H&E stained skin sections of Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− mice at E16.5 (a) and P0 (b). The dotted black line demarcates the epidermal-dermal boundary and the black arrows indicate HFs. E-Epidermis; D-Dermis. Scale Bar: 200μm. (c) Graph showing reduced number of HFs (Left) and number of HFs at each developmental stage (Right) at E16.5 in Ctip2−/− skin compared to Ctip2+/+ skin. (d) Bar graph shows reduced number of the total HFs (Left) and number of follicles in stages 1-6 (Right) in E18.5 Ctip2−/− skin section. (e) Bar graph representing total number of HFs and HFs in different stages at P0 skin. (*p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p<0.005)

The reduced hair follicle density in the Ctip2−/− mice during hair formation prompted us to investigate whether loss of CTIP2 alters expression of signaling cues that are important in HF formation. We observed down regulation of NOTCH1 and EGFR in Ctip2−/− HFs, particularly at E18.5 (Figure S1c and S1d), when the difference in HF density between Ctip2−/− and Ctip2+/+ was most striking (Figure 1d). In contrast, expression of Tcf3 and Lhx2 were up-regulated at E18.5 in Ctip2−/− skin (right panel of Figure S1e). Expression of Sox9, which plays an important role in HF cycling but not development (Vidal et al., 2005), was upregulated in Ctip2−/− skin at E18.5 (Figure right panel of S1e), whereas there was no change in expression of NFATC1, a transcription factor regulating only HF cycling (S1f-h). Expression of other key regulators, such as Bmp, Shh and Wnt were unaltered (Figure S1f). These results suggest that CTIP2 controls HF development by modulating expression of specific factors and signaling molecules involved in HF development.

Deregulated hair cycling in adult Ctip2ep−/− mice

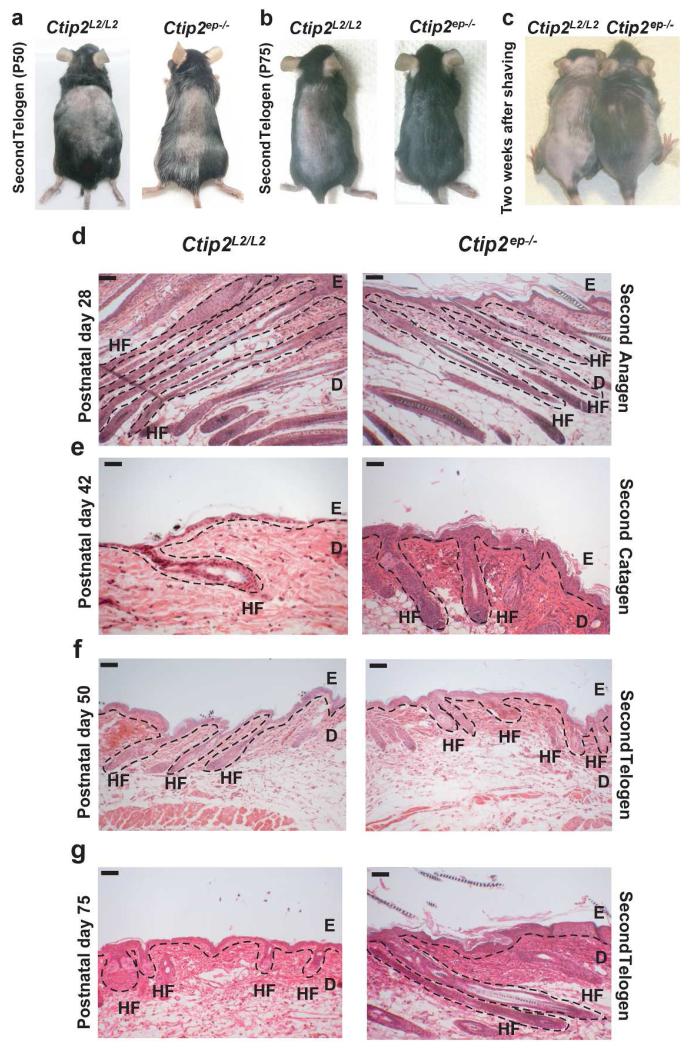

We analyzed the expression of CTIP2 during postnatal HF establishment and also at different phases of natural hair cycling (Figure S2a and S2b). The expression of CTIP2 was uniform throughout the HF at all stages (Figure S2b). CTIP2 expressions were also detected during depilation-induced hair cycling, with highest expression in anagen and comparably lower levels of expression in catagen and telogen (Liang et al., 2012). CTIP2 co-localizes with HFSC markers CD34 and K15 within the HF bulge region (Golonzhka et al., 2007), suggesting that CTIP2 may play a role in hair cycling of adult skin. Because Ctip2-null mice die shortly after birth, we used Ctip2ep−/− mice, selectively lacking Ctip2 in the epidermis (Golonzhka et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012) for all subsequent studies. HF formation and the first postnatal hair cycling were similar in Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin at P0, P7 and P21 (Figure S3a-c). During the second hair cycling, the pink coat color of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin at P50 confirmed that all the HFs were in telogen (Figure 2a). However, at P75 when Ctip2L2/L2 follicles were still in telogen, Ctip2ep−/− follicles had already entered anagen, as indicated by the black color of the Ctip2ep−/− skin (Figure 2b). Mutant mice grew hair much faster than Ctip2L2/L2 mice two weeks after shaving (Figure 2c), but the anagen-catagen-telogen transition progressed normally in Ctip2ep−/− mice at P28, P42 and P50 (Figure 2d, 2e and 2f). However, Ctip2ep−/− mice exhibited long anagen HFs compared to the short, resting HFs in the Ctip2L2/L2 mice at P75 (Figure 2g). To explore the role of CTIP2 in hair cycling further, we analyzed induced hair-cycling post depilation in 8 weeks old Ctip2ep−/− and Ctip2L2/L2 mice. The anagen-catagen-telogen transition proceeded normally in both groups of mice post-depilation (Figure S4a, S4c-e). However, after entering into telogen, Ctip2ep−/− HFs spontaneously entered anagen at day 28 post-depilation, whereas Ctip2L2/L2 HFs remained in telogen (Figure S4b and S4f, compare left and right panels). Based on the above results, we conclude that CTIP2 plays a key role in maintenance of natural and depilation induced hair cycling in adult skin.

Figure 2. Epidermal-specific deletion of Ctip2 alters hair cycling in adult skin.

(a-b) Macroscopic images of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice dorsal skin in second telogen at P50 (a) and P75 (b). Pink skin color in Ctip2L2/L2 mice indicates telogen phase and black skin color in Ctip2ep−/− mice indicates anagen phase. (c) Rapid dorsal hair growth in 8 week old Ctip2ep−/− mice compared to the Ctip2L2/L2 mice two weeks after shaving, (d-g) Hematoxylin and Eosin stained skin sections of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin at different stages of hair cycling, (d) P28 (Second Anagen), (e) P42 (Second Catagen), (f) P50 (Early Second Telogen) and (g) P75 (Late Second Telogen). HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis. Scale Bar: 200 μm.

Disruption of Ctip2 in the adult HFs enhances follicular stem cell activity

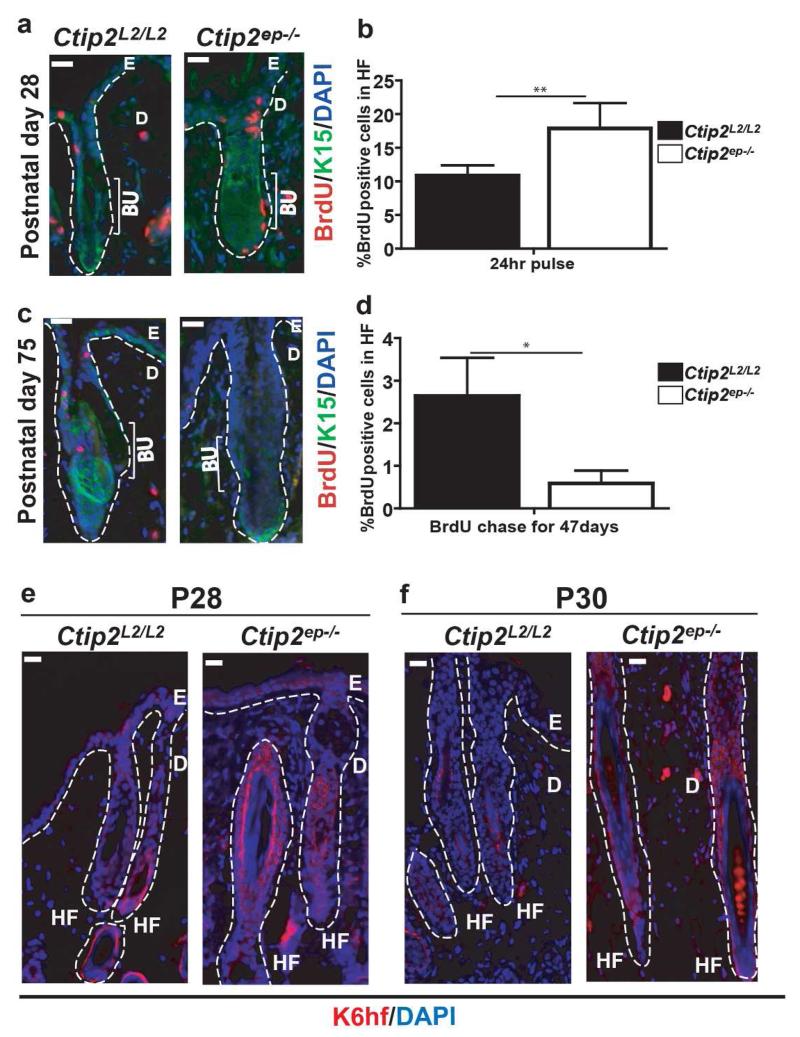

Normal hair cycling homeostasis is maintained by HFSCs and early induction of anagen is linked to altered activity of HFSCs (Cotsarelis et al., 1990; Morris and Potten, 1999; Sun et al., 1991). Premature induction of anagen in Ctip2ep−/− mice suggests a role of CTIP2 in controlling HFSC activity. To detect slow cycling hair follicle stem cells, BrdU pulse chase experiment was performed as described herein(Braun et al., 2003). Although there was no difference in hair morphology at P28, Ctip2ep−/− HFs incorporated more BrdU than Ctip2L2/L2 HFs after a pulse of 24 hrs (Figure 3a and b). However, this finding was reversed after a longer chase period of 47 days. At P75, the percentage of BrdU+ cells which also co-labeled with bulge specific SC marker K15 was significantly reduced in Ctip2ep−/− HFs (Figure 3c and d). These results indicate that loss of Ctip2 increases follicular SC proliferation which may lead to the exhaustion of the bulge stem cells at later stages of hair cycle. Moreover this enhancement of progenitor/stem cell proliferation may lead to their increased differentiation. Therefore we looked at the expression of K6HF,a marker of differentiation that is expressed in companion layer and also in upper matrix cells of hair bulb during anagen (Huelsken et al., 2001; Langbein et al., 1999; Winter et al., 1998). K6hf expression was increased in Ctip2ep−/− HFs at P28 and at P30 indicating accelerated differentiation of HF epithelial cells (Figure 3e and f).

Figure 3. Loss of Ctip2 in HF epithelium alters proliferation and differentiation in the HFs.

(a) Anti-BrdU immunolabeling of P28 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin 24 hrs after BrdU pulse. Sections were co-stained with K15, a bulge-specific marker. (b) Graph represents percentage of BrdU-positive cells in HFs. (c) Immunostaining after BrdU pulse and extended chase shows reduced number of BrdU-positive cells in P75 Ctip2ep−/− HFs. (d) Graphical representation of percentage of label retaining bulge cells in HFs. (e-f) Expression of K6hf was determined by immunostaining of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice skin at stages P28 (e) and P30 (f) using anti-K6hf antibody. Bu-Bulge; HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis; Scale Bar: 100μm

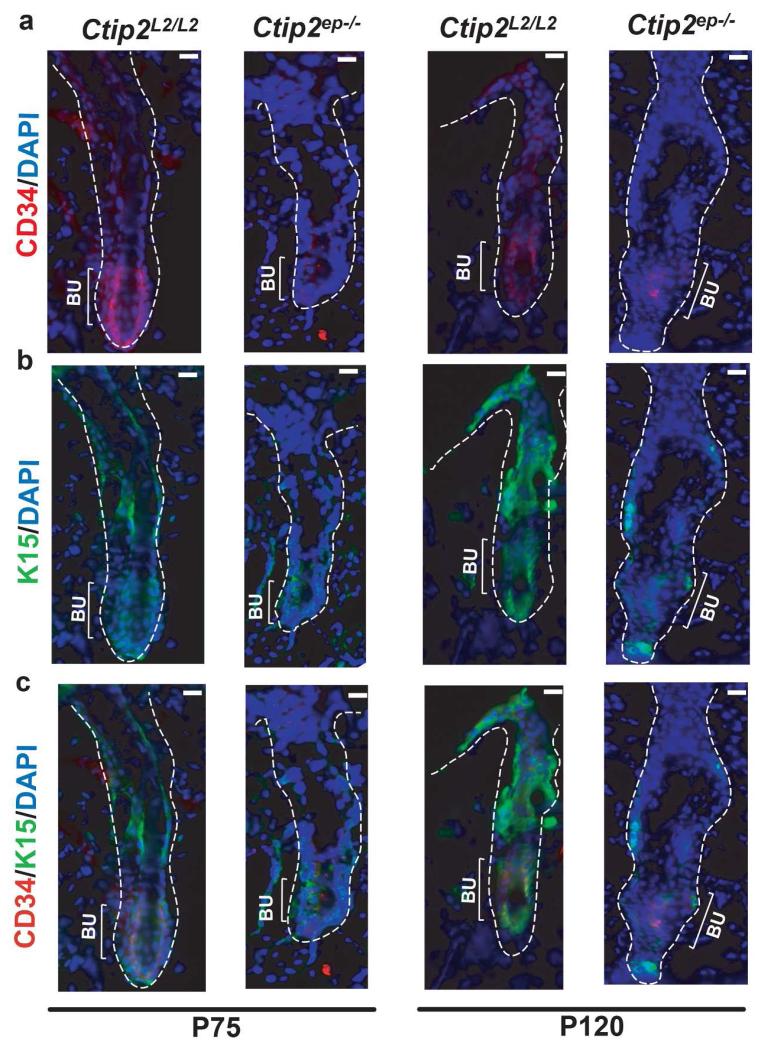

Since we observed a loss of BrdU+ label retaining cells in Ctip2ep−/− HFs at later time point we performed immunohistochemical analysis for expression of HF bulge specific stem cell markers CD34 and K15. Expression of both CD34 and K15, was significantly reduced at P75 in Ctip2ep−/− HFs compared to the Ctip2L2/L2 HFs (Figure S6a and Figure 4a, b and c). Similar downregulation of CD34 and K15 expression was observed in Ctip2ep−/− HFs at P120 (Figure 4a, b and c) when Ctip2ep−/− mice displayed a significant loss of dorsal hair (Figure S7a). Although, the total number of HFs between Ctip2ep−/− and Ctip2L2/L2 mice were unaltered at that stage (Figure S7b).

Figure 4. CTIP2 is essential for maintaining bulge stem cell pool.

(a) Immunostaining with anti-CD34 antibody (red) shows a decrease in CD34+ cells in HF bulge of Ctip2ep−/− dorsal skin compared to Ctip2L2/L2 at P120. At P75, similar expression of CD34 in HFs of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin was observed. (b) Staining with anti-K15 antibody (green) indicates reduced expression of K15 in hair follicle bulge region of Ctip2ep−/− dorsal skin compared to Ctip2L2/L2 at P120 but not at P75. (c) Co-localization of CD34 and K15 expression at P75 and P120 in HFs from Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice skin. All sections are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Bu-Bulge; Scale Bar: 100μm

In addition we examined HF apoptosis in the mutant mice because apoptosis of HF cells plays an important role in anagen-catagen-telogen transition during hair cycling (Botchkareva et al., 2006; Lindner et al., 1997; Paus et al., 1994). TUNEL assay revealed no difference in the number of apoptotic cells between Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− HFs at P42 (catagen phase) (Figure S5a and b). However, a significant decrease in apoptosis was observed in Ctip2ep−/− skin at P75 (Figure S5c and d). Altogether, our data for altered HFSC proliferation, differentiation and reduced expression of bulge specific stem cell markers indicate that CTIP2 is essential for maintaining bulge SC quiescence during hair cycling in adult murine skin.

CTIP2 regulates expression of NFATC1 and LHX2 in bulge SCs during hair cycling in adult skin

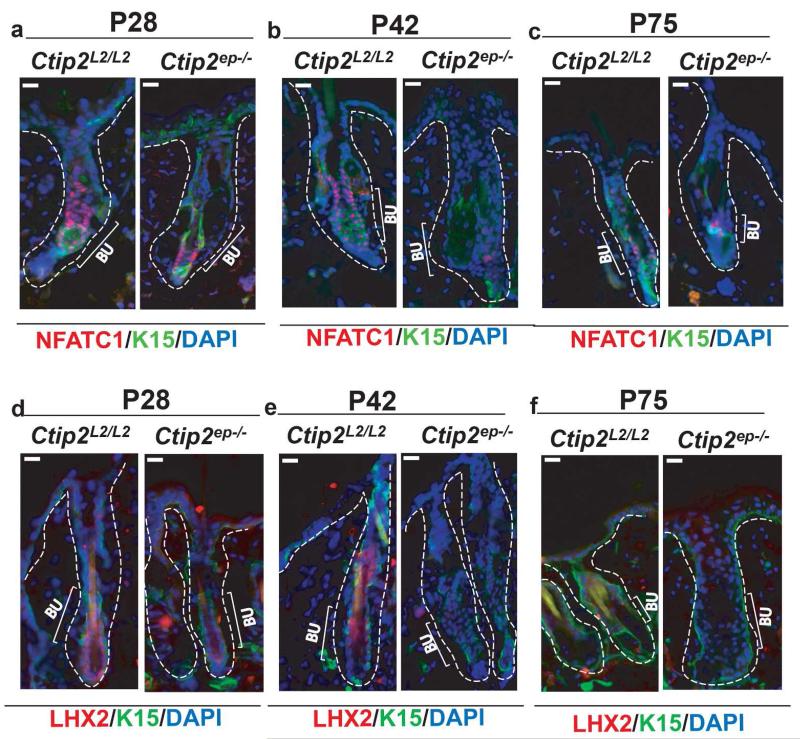

The transcription factors NFATC1 and LHX2 maintain the bulge SC pool in murine HFs (Horsley et al., 2008; Rhee et al., 2006). Grafting of Nfatc1- and Lhx2-null skin onto nude mice results in premature entry into anagen (Horsley et al., 2008; Rhee et al., 2006), which closely resembles the phenotype of Ctip2ep−/− mice (Figure 2b and g). We therefore investigated expression of both LHX2 and NFATC1 in adult Ctip2ep−/− mice throughout the different stages of hair cycling.

Expression of both Nfatc1 (Fig. 5a and b) and Lhx2 (Fig. 5d and e) was down-regulated in the HF bulge at P28 and P42 (see also Figure S6b). Nfatc1 expression continued to be down-regulated at P75 in mutant mice ( Figure 5c and Figure S6b), but the levels of Lhx2 (Fig. 5f) transcripts were indistinguishable and low in Ctip2ep−/− and control skin at this stage (Figure S6b). Expression of NOTCH1 and EGFR was unaltered in HFs of adult Ctip2ep−/− mice at P28 and P75 (Figure S7c, d and e).

Figure 5. Conditional ablation of Ctip2 in adult epidermis leads to altered expression of LHX2 and NFATC1.

(a-c) NFATC1 (red) and K15 (green) co-immunostaining of (a) P28, (b) P42 and (c) P75 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− dorsal skin was performed with anti-NFATC1 and -K15 antibodies (d-e) Immunohistochemical analysis of LHX2 expression in (d) P28 and (e) P42 HFs of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice indicates reduced expression of LHX2 in Ctip2ep−/− HF bulge and hair germ. (f) Immunostaining for LHX2 (red) at P75 on Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− dorsal skin shows no detectable expression in bulge region in both mice. All sections are co-stained with the K15 antibody and DAPI (blue) to stain bulge cells and cell nuclei respectively. Bu-Bulge; Scale Bar: 100μm.

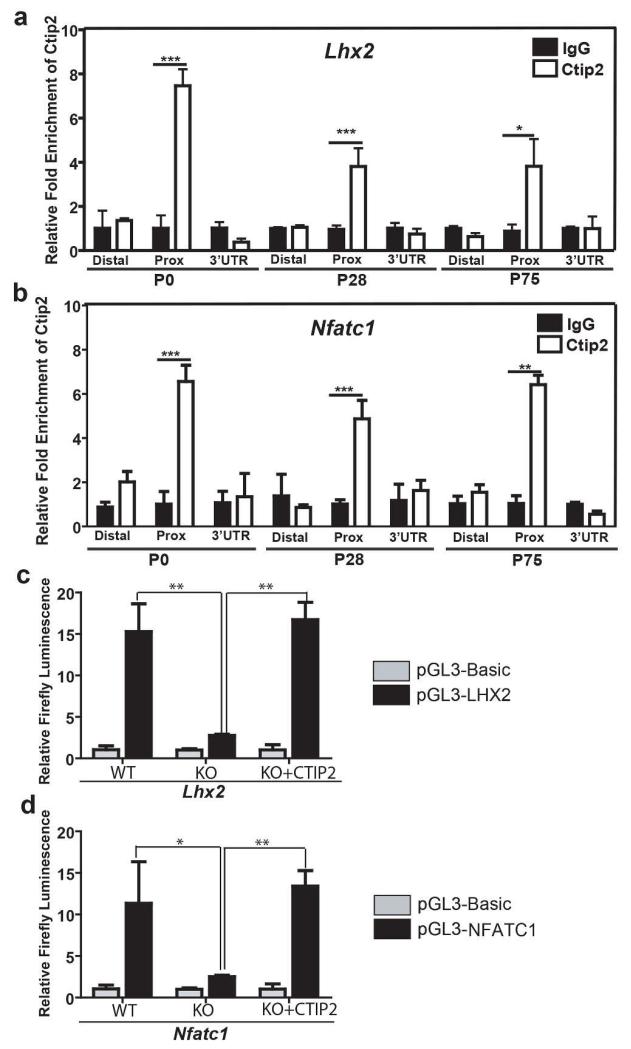

ChIP assays were performed in keratinocytes isolated from the epidermis of newborn (P0) and adult (P28 and P75) mice to determine if CTIP2 interacts with the regulatory regions of the Lhx2 and Nfatc1 loci (see Table S3 and Figure S8a and S8b for details). CTIP2 interacted with the proximal promoter region of both Lhx2 (Figure 6a) and Nfatc1 (Figure 6b) in primary keratinocytes during HF morphogenesis (P0), and adult hair cycling (P28 and P75; Figure 6a and b). Moreover, the corresponding promoter fragments from both genes were sufficient to confer positive transcriptional regulatory activity by CTIP2 using luciferase-based reporter constructs in Ctip2-null keratinocytes (Figure 6c and d). These results suggest that CTIP2 is a direct and positive regulator of Lhx2 and Nfatc1 expression, which may underlie the adult HF phenotype of Ctip2ep−/− mice.

Figure 6. CTIP2 positively regulates Lhx2 and Nfatc1 expression in skin keratinocytes in vitro.

(a and b) ChIP assays were performed on epidermal keratinocytes from P0, P28 and P75 mice using anti-CTIP2 antibody and the results were analyzed by primer sets indicated in Table S3. Rat IgG was used as the control. CTIP2 interacts with the proximal promoter regions of (a) Lhx2 and (b) Nfatc1. (c and d) CTIP2 positively regulates Lhx2 (a) and Nfatc1 (b) promoter in cultured keratinocytes. Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− keratinocytes were transfected with either promoter-less pGL3-basic construct or pGL3-basic construct harboring respective promoter regions with or without CTIP2 expression vector. For normalization renilla luciferase was co-transfected. Bars represent relative expression levels of firefly luciferase. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s un-paired t-test (*p<0.05;**p<0.01).

Discussion

The HF is considered a model system in stem cell (SC) biology because of its occupancy by multipotent SCs that underlie its self-renewal properties (Tiede et al., 2007; Waters et al., 2007). Here, we have investigated the role of transcription factor CTIP2 in HF morphogenesis and cycling. We show that CTIP2 regulates HF development during embryogenesis likely by regulating the NOTCH1 and EGFR signaling pathways. Expression of CTIP2 in the epithelium is important for maintaining postnatal hair cycle homeostasis. Epidermal-specific ablation of Ctip2 results in inappropriate activation of follicular SCs and subsequent, premature depletion of this niche. CTIP2 interacts with the promoter region of Lhx2 and Nfatc1, and positively regulates expression of the corresponding genes, suggesting that each is a bona fide target gene of this transcription factor. These findings are highly relevant because both LHX2 and NFATC1 are necessary for maintenance of hair cycling and HFSCs in adult skin.

Epithelial–mesenchymal interaction is required for formation of a mature hair follicle with hair shaft, root sheaths, and dermal papilla (Botchkarev and Paus, 2003; Millar, 2002). Loss of Ctip2 from both epidermal and dermal compartment in the skin of Ctip2-null mice results in reduced numbers and reduced conversion of HF progenitors from one stage to another stage during morphogenesis. This finding implies that CTIP2 plays an important role in HF formation. The hair formation defect evident in Ctip2-null mice was due to the aberrant expression of components of signaling pathways that underlie embryonic hair development. CTIP2 interacts with the NOTCH1 and EGFR promoters and positively regulates expression of both genes in the epidermis at E14.5 and E16.5 (Zhang et al., 2012). Similarly, both NOTCH1 and EGFR are down-regulated in HFs of Ctip2−/− mice at E18.5, which may contribute to the HF developmental phenotype of these mice. Notably, Egfr−/− mice also exhibit delayed HF development (Doma et al., 2013) and the NOTCH pathway plays an important role in follicular patterning during embryogenesis (Millar, 2002). Mis-expression of DELTA1, a ligand of NOTCH pathway, in epidermis promotes expression of NOTCH1 and accelerates placode formation (Crowe et al., 1998; Crowe and Niswander, 1998). This may explain, at least in part, the link between down-regulation of NOTCH1 and the delay in HF morphogenesis in Ctip2−/− mice. We have also observed up-regulation of Tcf3, Sox9 and Lhx2 expression in Ctip2−/− HFs. Tcf3 induction in skin maintains an undifferentiated state and arrests downward growth of HF (Nguyen et al., 2006). Therefore, Tcf3 overexpression may contribute in the delayed down-growth of HF progenitors in Ctip2−/− mice during development. However, the role(s) of over-expressed Sox9 and Lhx2 on the HF developmental phenotype in Ctip2−/− mice is unclear. SOX9 (Vidal et al., 2005) is thought to play no role in HF development. Although, we show that CTIP2 binds to Nfatc1 and Lhx2 promoter regions and increases expression of heterologous reporter constructs harboring these regions, Nfatc1 transcript levels were unaltered, while Lhx2 transcript was only modestly up-regulated in the embryonic Ctip2−/− skin, suggesting that other cis-acting regulatory elements or trans-acting factors may regulate expression of both genes during skin organogenesis and can compensate for loss of CTIP2. During osteoclastogenesis, it has been shown that co-stimulation of Fc receptor common γ chain (FcRγ) and DNAX-activating protein (DAP) 12 by RANKL drive phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) leading to calcium-mediated regulation of NFATC1 expression (Kim et al., 2012; Koga et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2006). Regulation of NFATC1 by these factors during hair formation and cycling has not been reported. It is possible that NFATC1 expression during embryogenesis can be predominantly regulated by these factors, without input from CTIP2.

To circumvent the postnatal lethality of Ctip2-null mice, we used Ctip2ep−/− mice to study the entire process of HF formation, establishment, and postnatal hair cycling. In contrast to the Ctip2-null mice, Ctip2ep−/− mice did not show differences in HF number or morphology during formation or the first postnatal hair cycling, suggesting that CTIP2 in dermis plays an essential role in HF morphogenesis through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Ctip2ep−/− mice exhibited a defect in the second phase of hair cycling with short telogen and early entry into anagen. This defect in hair cycling can be a synergy of the deletion of Ctip2 in keratinocytes of hair follicles and also from the paracrine signaling produced by the infiltrating cells in dermis due to inflammation in Ctip2ep−/− mice. Therefore both both cell and non-cell autonomous effects can contribute in abnormal hair cycling in Ctip2ep−/− mice. Moreover, genetic disruption of the transcriptional coactivator complex Med1 or of genes encoding transcription factors, such as Foxp1, Lhx2 and Nfatc1 generate phenotypically similar mice (Horsley et al., 2008; Leishman et al., 2013; Nakajima et al., 2013; Rhee et al., 2006; Tornqvist et al., 2010).These observations suggest that CTIP2 may genetically interact with these factors, regulate their expression and may also be involved in signaling pathway(s) which modulate hair cycling.

Activation of the bulge SCs is required for induction of anagen during normal hair cycling (Cotsarelis et al., 1990; Morris and Potten, 1999; Sun et al., 1991). Bulge SCs proliferate and give rise to transient amplifying cells, which in turn migrate towards secondary hair germ to initiate anagen (Cotsarelis et al., 1990; Sun et al., 1991).

Premature induction of anagen in Ctip2ep−/− mice is consistent with over-activation of bulge SCs and also an increase in HFSC differentiation. Enhanced SC activity appears to deplete the numbers of bulge SCs following ablation of Ctip2. This over-activation and eventual exhaustion of HFSCs may explain the loss of hair coat in Ctip2ep−/− mice at P120. In spite of the loss of hair coat, the number of HFs was not altered, suggesting that the loss of hair in mutant mice is most likely due to the loss of hair shaft or lack of shaft formation. Reduced expression of the bulge SC markers (CD34 and K15) in the Ctip2ep−/− HFs further indicates a role of CTIP2 for maintenance of the bulge stem cell quiescence and survival.

NFATC1 and LHX2 are known to regulate the switch between HFSC maintenance and activation (Horsley et al., 2008; Rhee et al., 2006). Loss of LHX2 leads to exhaustion of HFSCs and failure in anchorage of HFs (Folgueras et al., 2013). Moreover LHX2 plays a significant role in repithelialization after injury by regulating SOX9, TCF4 and LGR5 (Mardaryev et al., 2011). In our present study, we observed down-regulation of LHX2 and NFATC1 in Ctip2ep−/− HFs during hair cycling, and direct regulation of the corresponding promoters by CTIP2. Down-regulation of both of those genes may lead to enhanced SC activity and later depletion of HFSCs in Ctip2ep−/− mice. The difference in LHX2 and NFATC1 expression patterns observed between Ctip2-null embryonic skin and Ctip2ep−/− adult skin might be due to the temporal regulation of those genes by CTIP2 during development and in adulthood. These findings, along with our previously published data, demonstrate that CTIP2 is a top level transcription factor that performs a variety of functions, ranging from control of HF development, cycling and EPB formation, suppression of inflammation, maintenance of homeostasis and regeneration in skin. The pivotal role of CTIP2 in a variety of developmental processes makes it an ideal target for treatment of dermatological diseases, such as alopecia, chronic wounds and atopic dermatitis (eczema).

Materials and Methods

Mice

Ctip2−/− and Ctip2ep−/− mice were previously described (Golonzhka et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2L2/L2 mice were used as controls. Six to eight mice from multiple litters were used in each group and at each time point. Mice are maintained in a specific pathogen free environment with constant temperature control. Animal work was approved by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hair cycle stages

Dorsal skin samples were harvested from mice from E14.5 to P0 for hair follicle morphogenesis studies as described (Paus et al., 1999). First hair cycle (P9, P16 and P19) and second hair cycle (P28, P42, P49 and P75) samples were similarly collected. Depilation was performed on 8-week old mice and skin biopsies were taken on day 7 (anagen), day 17 (catagen), day 21 (telogen) and day 28 after depilation.

A detailed description of histology, immunohistochemistry, BrdU labeling and detection, TUNEL assays, qRT PCR, ChIP, luciferase assays and statistics are available in the Supplementary Materials and Methods section.

Supplementary Material and Methods

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Dorsal skin samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Deparaffinization and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining was performed for histological analysis. For immunohistochemical (IHC) study, antigen unmasking with citrate buffer was performed as described (Golonzhka et al., 2009; Hyter et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum and primary antibody was added after blocking. Subsequently, sections were incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with Cy3 or Cy2, and DAPI for nuclei staining. Images were taken at 20X and 40X magnification using Leica DMRA fluorescent microscope and Hamamatsu C4742-95 digital camera and were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS3. IHC data were quantified using Adobe Photoshop CS3 and Image J software. Table S1 shows the details of antibody used for immunohistochemistry.

BrdU labeling and detection

Groups of mice were injected with 100 μg/g BrdU (Sigma) and dorsal skin samples were collected after 24 hrs for short-pulse analyses. Long-chase animals were injected with 50 μg/g of BrdU every 12 hours for a total four injections and skin biopsies were taken after a 47-day chase period (Braun et al., 2003). Anti-BrdU staining (Serotec, Raleigh, NC, 1:200) was performed on paraffin sections to detect proliferating S-phase cells. Additional detail on BrdU staining is described in the Histology and Immunohistochemistry section.

TUNEL assay

Dorsal skin samples were fixed in 4% PFA and deparaffinized slides were subjected to TUNEL staining using the fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega, no. TB235). The detailed protocol has been previously described in (Hyter et al., 2013).

Statistics

Statistical significance between the two groups was analyzed by Graphpad Prism software (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA) using unpaired Student t-test. The TUNEL- or BrdU-positive cells were counted and represented as a percentage of DAPI-positive cells. Multiple sections were analyzed for each genotype and for time point. Data from each group for each time point were combined for calculating the mean data and SEM and significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t-test.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the epidermis of mouse skin and cDNA was synthesized from extracted RNA as described (Indra et al., 2005b). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system using SYBR Green methodology (Indra et al., 2005a; Indra et al., 2005b). Using HPRT as an internal control, relative gene expression of the RT-qPCR data was analyzed. The mean threshold cycle (Ct) for individual reactions was determined by using the ABI sequence analysis software. Primer sequences for qPCR are indicated Table S2. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP studies were performed on epidermal tissue from newborn and adult mice. Cells from epidermis were isolated from newborn mice as described (Zhang et al., 2012) and from adult mice (Nowak and Fuchs, 2009). Successively cells were processed for ChIP as we previously described (Hyter et al., 2010) using appropriate antibodies. Recovered DNA was amplified by qPCR using primers specific for the distal or proximal regions of the promoters of Lhx2 and Nfatc1, as well as primer sets for 3′ UTR (untranslated regions) of each gene. Proximal region is considered as 1.5 kb in and around the transcriptional start site (TSS). Distal region is indicated as sequences 2kb or beyond upstream of TSS. Primers used for individual ChIP assay are indicated in Table S3.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

Lhx2 and Nfatc1 promoter reporter constructs were prepared by inserting respective sequences from region as described in Table S4 into the promoterless luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-Basic (Promega). Correct insertions were verified by sequence analysis. Primary keratinocytes were isolated from P0 pup skin as described (Zhang et. al., 2012). Approximately 5 × 104 cells were individually transfected with 200ng of Lhx2 and Nfatc1 reporter constructs, 20ng of pcDNA3 containing Ctip2 (or empty vector) and 8ng of renilla luciferase construct using the Neon transfection system (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were plated in collagen-coated, 96-well plate. Dual luciferase reporter assay was performed 48hrs after transfection using kit from Promega and synergy HT Multi-Mode microplate reader.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Histological analysis and expression of factors involved in HF morphogenesis in Ctip2-null skin. (a) Hematoxylin and Eosin stained Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin sections at E14.5. Black arrows indicate HFs. (b) Bar graph representing total number of HFs at E14.5. (c-d) NOTCH1 (c) and EGFR (d) immunostaining in E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. (e) RT-qPCR analysis of Sox9, Lhx2 and Tcf3 expression in E14.5 and E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. (f) RT-qPCR analysis of BMP2, NFATC1, SHH and WNT in E14.5 and E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. The mean-threshold cycle for individual reactions was normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01). (g-h) Immunohistochemical analysis of NFATC1 expression in Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin at E18.5 (g) and P0 (h) stages. DAPI is used as counterstain. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 2. CTIP2 expression during follicular morphogenesis and hair cycling. (a) Schematic diagram showing the different stages of hair cycling at which skin samples were collected from Ctip2L2/L2 mice for IHC analysis of CTIP2 distribution. (b) CTIP2 immmunostaining using anti-CTIP2 antibody reveals CTIP2 expression throughout the hair follicle during morphogenesis (P7 and P14) and hair cycling (P14 to P81). Sections were also co-stained with K15, a bulge-specific marker. DAPI (blue) counterstaining was performed to label cell nuclei. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 3. Hair follicle defects were not observed during follicular establishment and during first hair cycling phase in Ctip2ep−/− mice (a-c) H&E staining of dorsal skin sections from Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice at (a) P0, (b) First anagen (P7) and (c) First Telogen (P21). E-Epidermis; D-Dermis. Scale Bar: 200 μm

Supplementary Figure 4. Ctip2 has a role in depilation induced hair cycling in adult mice (a-b) Macroscopic images of dorsal skin of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice (a) 21 days and (b) 28 days after depilation. Note the dorsal skin color of Ctip2ep−/− mice was black indicating anagen compared to the pink skin color of Ctip2L2/L2 indicating telogen at day 28. (c-e) H&E stained skin sections of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice at (c) Day7, (d) Day17, (e) Day 21 and (f) Day 28 after depilation. On Day 28 post-depilation, the hair follicles in Ctip2ep−/− mice have entered anagen compared to Ctip2L2/L2 mice, which are still in telogen (f). HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis; Scale Bar: 200 μm

Supplementary Figure 5. Ablation of Ctip2 from epidermis and hair follicle lead to altered cell survival specifically in HF (a-d) TUNEL assay was performed on P42 (a) and P75 (c) Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin and graph represents the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in HFs of P42 (b) and P75 (d) skin. (*p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01). E-Epidermis, D-Dermis and HF-Hair Follicle. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 6. Expression of genes encoding stem cell markers and regulators of hair cycling in adult mice skin (a) RT-qPCR analyses of CD34 and K15 mRNA levels at P75 and P120. (b-d) P28, P42 and P75 dorsal skin was harvested from Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice for RT-qPCR analyses of Lhx2 and Nfatc1. For RT-qPCR bar represents mean expression of levels of indicated genes normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT. The mean threshold cycle (Ct) for individual reactions was determined by using the ABI sequence analysis software. (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01).

Supplementary Figure 7. Loss of hair coat in Ctip2ep−/− mice and expression of factors involved in hair cycling in the Ctip2ep−/− skin (a) Macroscopic images of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice dorsal skin at P120 (b) Hematoxylin- and Eosin-stained skin of P120 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice. (c) RT-qPCR analyses of Notch1 and Egfr were performed on P28 and P75 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin. The mean threshold cycle for individual reactions with respect to HPRT was determined by using the ABI sequence analysis software. (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01). (d-e) Immunostaining was performed on P28 and P75 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin for NOTCH1 (d) and EGFR (e). DAPI was used for staining nuclei. HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis; Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 8. Schematic diagram indicating binding region of CTIP2 on the Lhx2 and Nfatc1 promoters. The CTIP2 binding regions on the Lhx2 (a) and Nfatc1 (b) genome are indicated, as well as the proximal and distal promoter regions. Arrows indicate regions of primer sets. Primers set details are listed in Table S3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Indra lab and the OSU College of Pharmacy, specifically Dr. Mark Zabriskie and Dr. Gary Delander of the OSU College of Pharmacy for continuous support and encouragement. These studies were supported by grants AR056008 (AI) from National Institute of Health and a Medical Research Foundation of Oregon grant (GI).

Abbreviations

- CTIP2

Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP TF)-interacting protein 2, also known as BCL11B

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- NOTCH1

Neurogenic Locus Notch Homolog Protein 1

- LHX2

LIM Homeobox 2

- NFATC1

Nuclear factor of activated T cells cytoplasmic calcineurin-dependent 1

- WNT

Wingless Type MMTV Integration Site Family

- β-catenin

Beta catenin

- LEF1

Lymphoid Enhancer-Binding Factor 1

- TCF3

Transcription Factor 3

- SHH

Sonic Hedgehog

- BMP

Bone Morphogenetic Protein

- Sox9

Sex Determining Region Y-Box 9

- K14

Keratin 14

- LoxP

locus of X-over P1

- K15

Keratin15

- HF

Hair Follicle

- SC

Stem Cell

- BrdU

Bromodeoxyuridine

- qRT PCR

quantitative real time reverse transcription PCR

- EPB

Epidermal Permeability Barrier

- ChIP

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, et al. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Developmental cell. 2002;2:643–53. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram D, Fields A, Pretty On Top K et al. Isolation of a novel family of C(2)H(2) zinc finger proteins implicated in transcriptional repression mediated by chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) orphan nuclear receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:10315–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram D, Fields A, Senawong T, et al. COUP-TF (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor)-interacting protein 1 (CTIP1) is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. The Biochemical journal. 2002;368:555–63. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Roth W, et al. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nature cell biology. 1999;1:158–64. doi: 10.1038/11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Paus R. Molecular biology of hair morphogenesis: development and cycling. Journal of experimental zoology Part B, Molecular and developmental evolution. 2003;298:164–80. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkareva NV, Ahluwalia G, Shander D. Apoptosis in the hair follicle. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2006;126:258–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, et al. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 2003;130:5241–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Swan RZ, Grachtchouk M, et al. Essential role for Sonic hedgehog during hair follicle morphogenesis. Developmental biology. 1999;205:1–9. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 1990;61:1329–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe R, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, et al. A new role for Notch and Delta in cell fate decisions: patterning the feather array. Development. 1998;125:767–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe R, Niswander L. Disruption of scale development by Delta-1 misexpression. Developmental biology. 1998;195:70–4. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doma E, Rupp C, Baccarini M. EGFR-ras-raf signaling in epidermal stem cells: roles in hair follicle development, regeneration, tissue remodeling and epidermal cancers. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:19361–84. doi: 10.3390/ijms141019361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgueras AR, Guo X, Pasolli HA, et al. Architectural niche organization by LHX2 is linked to hair follicle stem cell function. Cell stem cell. 2013;13:314–27. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafter-Gvili A, Sredni B, Gal R, et al. Cyclosporin A-induced hair growth in mice is associated with inhibition of calcineurin-dependent activation of NFAT in follicular keratinocytes. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2003;284:C1593–603. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00537.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonzhka O, Leid M, Indra G, et al. Expression of COUP-TF-interacting protein 2 (CTIP2) in mouse skin during development and in adulthood. Gene expression patterns: GEP. 2007;7:754–60. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonzhka O, Liang X, Messaddeq N, et al. Dual role of COUP-TF-interacting protein 2 in epidermal homeostasis and permeability barrier formation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009;129:1459–70. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LA, Alexander N, Hogan ME, et al. Genetically null mice reveal a central role for epidermal growth factor receptor in the differentiation of the hair follicle and normal hair development. The American journal of pathology. 1997;150:195975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V, Aliprantis AO, Polak L, et al. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. beta-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, et al. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nature medicine. 2005;11:1351–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Kim JH, Moon JB, et al. The transmembrane adaptor protein, linker for activation of T cells (LAT), regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Molecules and cells. 2012;33:401–6. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Inui M, Inoue K, et al. Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature. 2004;428:758–63. doi: 10.1038/nature02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langbein L, Rogers MA, Winter H, et al. The catalog of human hair keratins. I. Expression of the nine type I members in the hair follicle. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:19874–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Tumbar T. Hairy tale of signaling in hair follicle development and cycling. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2012;23:906–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leishman E, Howard JM, Garcia GE, et al. Foxp1 maintains hair follicle stem cell quiescence through regulation of Fgf18. Development. 2013;140:3809–18. doi: 10.1242/dev.097477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Bhattacharya S, Bajaj G, et al. Delayed cutaneous wound healing and aberrant expression of hair follicle stem cell markers in mice selectively lacking Ctip2 in epidermis. PloS one. 2012;7:e29999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Kao CH, Lin KM, et al. Notch signaling regulates late-stage epidermal differentiation and maintains postnatal hair cycle homeostasis. PloS one. 2011;6:e15842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner G, Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, et al. Analysis of apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen) The American journal of pathology. 1997;151:1601–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KM, Pelton RW, Hogan BL. Organogenesis and pattern formation in the mouse: RNA distribution patterns suggest a role for bone morphogenetic protein-2A (BMP 2A) Development. 1990;109:833–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao D, Epple H, Uthgenannt B, et al. PLCgamma2 regulates osteoclastogenesis via its interaction with ITAM proteins and GAB2. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2869–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI28775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardaryev AN, Meier N, Poterlowicz K, et al. Lhx2 differentially regulates Sox9, Tcf4 and Lgr5 in hair follicle stem cells to promote epidermal regeneration after injury. Development. 2011;138:4843–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.070284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill BJ, Gat U, DasGupta R, et al. Tcf3 and Lef1 regulate lineage differentiation of multipotent stem cells in skin. Genes & development. 2001;15:1688–705. doi: 10.1101/gad.891401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SE. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2002;118:216–25. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Potten CS. Highly persistent label-retaining cells in the hair follicles of mice and their fate following induction of anagen. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1999;112:470–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillas R, Larcher F, Conti CJ, et al. Expression of a dominant negative mutant of epidermal growth factor receptor in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking alterations in hair follicle development and skin structure. The EMBO journal. 1995;14:5216–23. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Inui S, Fushimi T, et al. Roles of MED1 in quiescence of hair follicle stem cells and maintenance of normal hair cycling. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2013;133:354–60. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Schneider MR, Schmidt-Ullrich R, et al. Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis, cycling, and/or structure: an update. Journal of dermatological science. 2013;69:6–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Rendl M, Fuchs E. Tcf3 governs stem cell features and represses cell fate determination in skin. Cell. 2006;127:171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Handjiski B, Czarnetzki BM, et al. A murine model for inducing and manipulating hair follicle regression (catagen): effects of dexamethasone and cyclosporin A. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1994;103:143–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12392542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Muller-Rover S, Van Der Veen C, et al. A comprehensive guide for the recognition and classification of distinct stages of hair follicle morphogenesis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1999;113:523–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee H, Polak L, Fuchs E. Lhx2 maintains stem cell character in hair follicles. Science. 2006;312:1946–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1128004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Current biology: CB. 1998;8:1058–68. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TT, Cotsarelis G, Lavker RM. Hair follicular stem cells: the bulge-activation hypothesis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1991;96:77S–8S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12471959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiede S, Kloepper JE, Bodo E, et al. Hair follicle stem cells: walking the maze. European journal of cell biology. 2007;86:355–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornqvist G, Sandberg A, Hagglund AC, et al. Cyclic expression of lhx2 regulates hair formation. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyttendaele H, Panteleyev AA, de Berker D, et al. Activation of Notch1 in the hair follicle leads to cell-fate switch and Mohawk alopecia. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2004;72:396–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07208006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclair S, Nicolas M, Barrandon Y, et al. Notch1 is essential for postnatal hair follicle development and homeostasis. Developmental biology. 2005;284:184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal VP, Chaboissier MC, Lutzkendorf S, et al. Sox9 is essential for outer root sheath differentiation and the formation of the hair stem cell compartment. Current biology: CB. 2005;15:1340–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhang LJ, Guha G, et al. Selective ablation of Ctip2/Bcl11b in epidermal keratinocytes triggers atopic dermatitis-like skin inflammatory responses in adult mice. PloS one. 2012;7:e51262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters JM, Richardson GD, Jahoda CA. Hair follicle stem cells. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2007;18:245–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Langbein L, Praetzel S, et al. A novel human type II cytokeratin, K6hf, specifically expressed in the companion layer of the hair follicle. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1998;111:955–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LJ, Bhattacharya S, Leid M, et al. Ctip2 is a dynamic regulator of epidermal proliferation and differentiation by integrating EGFR and Notch signaling. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:5733–44. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary References

- Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, et al. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 2003;130:5241–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonzhka O, Liang X, Messaddeq N, et al. Dual role of COUP-TF-interacting protein 2 in epidermal homeostasis and permeability barrier formation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009;129:1459–70. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyter S, Bajaj G, Liang X, et al. Loss of nuclear receptor RXRalpha in epidermal keratinocytes promotes the formation of Cdk4-activated invasive melanomas. Pigmen cell & melanoma research. 2010;23:635–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyter S, Coleman DJ, Ganguli-Indra G, et al. Endothelin-1 is a transcriptional target of p53 in epidermal keratinocytes and regulates ultraviolet-induced melanocyte homeostasis. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2013;26:247–58. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra AK, Dupe V, Bornert JM, et al. Temporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis in embryonic surface ectoderm and fetal epidermal keratinocytes unveils two distinct developmental functions of BRG1 in limb morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Development. 2005a;132:4533–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.02019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra AK, Mohan WS, 2nd, Frontini M, et al. TAF10 is required for the establishment of skin barrier function in foetal, but not in adult mouse epidermis. Developmental biology. 2005b;285:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Bhattacharya S, Bajaj G, et al. Delayed cutaneous wound healing and aberrant expression of hair follicle stem cell markers in mice selectively lacking Ctip2 in epidermis. PloS one. 2012;7:e29999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JA, Fuchs E. Isolation and culture of epithelial stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;482:215–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LJ, Bhattacharya S, Leid M, et al. Ctip2 is a dynamic regulator of epidermal proliferation and differentiation by integrating EGFR and Notch signaling. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:5733–44. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Histological analysis and expression of factors involved in HF morphogenesis in Ctip2-null skin. (a) Hematoxylin and Eosin stained Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin sections at E14.5. Black arrows indicate HFs. (b) Bar graph representing total number of HFs at E14.5. (c-d) NOTCH1 (c) and EGFR (d) immunostaining in E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. (e) RT-qPCR analysis of Sox9, Lhx2 and Tcf3 expression in E14.5 and E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. (f) RT-qPCR analysis of BMP2, NFATC1, SHH and WNT in E14.5 and E18.5 Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin. The mean-threshold cycle for individual reactions was normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01). (g-h) Immunohistochemical analysis of NFATC1 expression in Ctip2+/+ and Ctip2−/− skin at E18.5 (g) and P0 (h) stages. DAPI is used as counterstain. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 2. CTIP2 expression during follicular morphogenesis and hair cycling. (a) Schematic diagram showing the different stages of hair cycling at which skin samples were collected from Ctip2L2/L2 mice for IHC analysis of CTIP2 distribution. (b) CTIP2 immmunostaining using anti-CTIP2 antibody reveals CTIP2 expression throughout the hair follicle during morphogenesis (P7 and P14) and hair cycling (P14 to P81). Sections were also co-stained with K15, a bulge-specific marker. DAPI (blue) counterstaining was performed to label cell nuclei. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 3. Hair follicle defects were not observed during follicular establishment and during first hair cycling phase in Ctip2ep−/− mice (a-c) H&E staining of dorsal skin sections from Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice at (a) P0, (b) First anagen (P7) and (c) First Telogen (P21). E-Epidermis; D-Dermis. Scale Bar: 200 μm

Supplementary Figure 4. Ctip2 has a role in depilation induced hair cycling in adult mice (a-b) Macroscopic images of dorsal skin of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice (a) 21 days and (b) 28 days after depilation. Note the dorsal skin color of Ctip2ep−/− mice was black indicating anagen compared to the pink skin color of Ctip2L2/L2 indicating telogen at day 28. (c-e) H&E stained skin sections of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice at (c) Day7, (d) Day17, (e) Day 21 and (f) Day 28 after depilation. On Day 28 post-depilation, the hair follicles in Ctip2ep−/− mice have entered anagen compared to Ctip2L2/L2 mice, which are still in telogen (f). HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis; Scale Bar: 200 μm

Supplementary Figure 5. Ablation of Ctip2 from epidermis and hair follicle lead to altered cell survival specifically in HF (a-d) TUNEL assay was performed on P42 (a) and P75 (c) Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin and graph represents the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in HFs of P42 (b) and P75 (d) skin. (*p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01). E-Epidermis, D-Dermis and HF-Hair Follicle. Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 6. Expression of genes encoding stem cell markers and regulators of hair cycling in adult mice skin (a) RT-qPCR analyses of CD34 and K15 mRNA levels at P75 and P120. (b-d) P28, P42 and P75 dorsal skin was harvested from Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice for RT-qPCR analyses of Lhx2 and Nfatc1. For RT-qPCR bar represents mean expression of levels of indicated genes normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT. The mean threshold cycle (Ct) for individual reactions was determined by using the ABI sequence analysis software. (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01).

Supplementary Figure 7. Loss of hair coat in Ctip2ep−/− mice and expression of factors involved in hair cycling in the Ctip2ep−/− skin (a) Macroscopic images of Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice dorsal skin at P120 (b) Hematoxylin- and Eosin-stained skin of P120 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− mice. (c) RT-qPCR analyses of Notch1 and Egfr were performed on P28 and P75 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin. The mean threshold cycle for individual reactions with respect to HPRT was determined by using the ABI sequence analysis software. (*p< 0.05 and ** p< 0.01). (d-e) Immunostaining was performed on P28 and P75 Ctip2L2/L2 and Ctip2ep−/− skin for NOTCH1 (d) and EGFR (e). DAPI was used for staining nuclei. HF- Hair Follicle; E- Epidermis; D- Dermis; Scale Bar: 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 8. Schematic diagram indicating binding region of CTIP2 on the Lhx2 and Nfatc1 promoters. The CTIP2 binding regions on the Lhx2 (a) and Nfatc1 (b) genome are indicated, as well as the proximal and distal promoter regions. Arrows indicate regions of primer sets. Primers set details are listed in Table S3.