Abstract

Water that is bound to bone’s matrix is implied as a predictor of fracture resistance; however, bound water is an elusive variable to be measured nondestructively. To date, the only nondestructive method used for studying bone hydration status is magnetic resonance variants (NMR or MRI). For the first time, bone hydration status was studied by short-wave infrared (SWIR) Raman spectroscopy to investigate associations of mineral-bound and collagen-bound water compartments with mechanical properties. Thirty cortical bone samples were used for quantitative Raman-based water analysis, gravimetric analysis, porosity measurement, and biomechanical testing. A sequential dehydration protocol was developed to replace unbound (heat drying) and bound (ethanol treatment) water in bone. Raman spectra were collected serially to track the OH-stretch band during dehydration. Four previously identified peaks were investigated: I3220/I2949, I3325/I2949 and I3453/I2949 reflect status of organic-matrix related water (mostly collagen-related water) compartments and collagen portion of bone while I3584/I2949 reflects status of mineral-related water compartments and mineral portion of bone. These spectroscopic biomarkers were correlated with elastic and post-yield mechanical properties of bone. Collagen-water related biomarkers (I3220/I2949 and I3325/I2949) correlated significantly and positively with toughness (R2=0.81 and R2=0.79; p<0.001) and post-yield toughness (R2=0.65 and R2=0.73; p<0.001). Mineral-water related biomarker correlated significantly and negatively with elastic modulus (R2=0.78; p<0.001) and positively with strength (R2=0.46; p < 0.001). While MR-based techniques have been useful in measuring unbound and bound water, this is the first study which probed bound-water compartments differentially for collagen and mineral-bound water. For the first time, we showed an evidence for contributions of different bound-water compartments to mechanical properties of wet bone and the reported correlations of Raman-based water measurements to mechanical properties underline the necessity for enabling approaches to assess these new biomarkers noninvasively in vivo to improve the current diagnosis of those who may be at risk of bone fracture due to aging and diseases.

Keywords: Water, Bone, Raman Spectroscopy, Mechanical Properties, Collagen, Mineral

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal fragility due to the aging and disease (i.e., osteoporosis, osteopetrosis and osteopenia) is a major social-health problem affecting the lives of millions of people.(1) Accurate assessment of fracture risk would help timely inception of therapy or help avoid unnecessary treatments. Bone mineral density (BMD)-based diagnosis cannot assess bone fragility with high accuracy (2, 3) and there is a need for more accurate diagnostic techniques. To address this need, a refined assessment of fracture risk independently of BMD would be valuable. Recent years have seen the elucidation of the water portion of bone in terms of its effects on bone’s fracture resistance.(4-9) In this perspective, clear understanding the involvement of water to bone’s mechanical integrity could be central to this effort and would contribute to the improvement fracture risk assessment.

Water is an abundant component of bone, up to 20% of trabecular bone (10) and approximately 10% of cortical bone’s wet weight is water.(11) Water in bone mainly exists in three different forms: (i) structural (molecular) water as part of the collagen and mineral structure; (ii) unbound water within the microscopic pores (Haversian canals, canaliculi, and lacunae spaces)(12), and (iii) water that is bound to the collagen (13, 14) and mineral (15) surfaces of bone. While only about 20% of the total water in bone exists in the unbound state, the majority of the water is bound to bone matrix.(16, 17) Distribution of unbound and bound water amount is a function of gender, disease, and age; and is also associated with collagen cross-linking, in the degree of mineralization of bone, and porosity as well.(10, 18-20) While total water content shows an inverse relationship with mineral content of bone (8, 11), bone matrix density is associated with bound water concentration.(21, 22)

Despite known effects of dehydration on dried bone mechanical properties (4, 23, 24), the exact function and contribution of different water compartments to bone mechanical integrity is not fully understood since bound water is an elusive variable to be measured nondestructively. The only nondestructive method used for studying bone hydration status is magnetic resonance variants (NMR or MRI). The assignment of the data obtained from MR-based techniques to specific water compartments of bone is phenomenological and implicit. NMR-based techniques require ultrahigh-quality NMR data for accurate estimation of the water compartments in bone.(7) MR-based techniques mostly detect signal from water bound to organic matrix (e.g., collagen) and unbound water (5-7), but they do not provide information on water that is bound to mineral exclusively. These techniques are not also able to distinguish among the bound water compartments that have various energy levels.(6) Few studies investigated the effects of unbound and bound water on bone mechanical properties using MR-based techniques.(5-9) To date, the correlations of bound water to bone mechanical properties have not been investigated by a secondary method other than MR-based techniques. Furthermore, the contribution of water bound to mineral or water compartments which are bound to collagen with different energy levels are not investigated. Therefore, a broader range of methods are needed to infer the status of water compartments that may independently a role in contributing to bone mechanical properties.

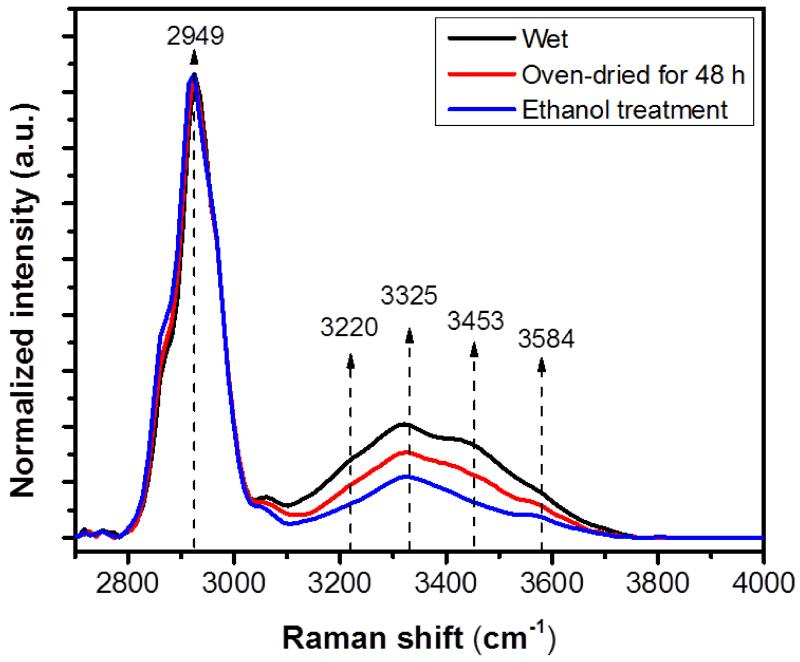

Raman spectroscopy is one of the few nondestructive modalities to assess the hydration status in bone. Raman spectroscopy can provide unique information on the type of water with various energy levels and the moiety to which water molecules are bound to (25). Raman spectroscopy has not been used to study the OH-stretch band in bone since the commercial Raman systems lack sensitivity into the OH-stretch range. Recently, we developed a custom designed short-wave infrared (SWIR) Raman spectroscopy system to identify the water compartments of bone with the moiety to which water molecules are bound to.(25) Using SWIR Raman spectroscopy, we previously identified four peaks in OH-stretch band of bone that were sensitive to sequential dehydration (25): the first peak is at 3220 cm−1 and belongs to solely organic matrix-related water (mostly collagen-related water), the second peak at 3325 cm−1 belongs to NH groups in collagen (backbone of collagen) beside organic matrix-related water (mostly collagen-related water), the third one at 3453 cm−1 belongs to OH of hydroxyproline (Hyp) beside mostly collagen-related water, and the last one at 3584 cm−1 belongs to OH of mineral and mineral-related water (Fig. 1). Among these four peaks, we found that 3325 and 3584 cm−1 were more tightly bound to the matrix than the remaining bands based on the rate at which they were replaced by deuterium oxide (D20). Using these four peaks, we developed four new spectroscopic biomarkers: I3220/I2949, I3325/I2949 and I3453/I2949 reflect status of mostly collagen-related water compartments and collagen portion of bone while I3584/I2949 reflects status of mineral-related water compartments and mineral portion of bone. This knowledge lent itself to the investigation of the association of these peak ratio intensities with bone mechanical properties. The purpose of the current study was to assess the association between these new spectroscopic biomarkers and bone mechanical properties as a potential predictive of bone quality in terms of bone hydration. Specifically, using these new spectroscopic biomarkers, we aimed to assess contributions of different water compartments in bone to elastic and post-yield mechanical properties of bone.

Figure 1.

Average Raman intensity changes of bone during sequential dehydration in an oven for 48 h followed by ethanol treatment. There was a gradual decline in the Raman intensities of bone’s OH-stretch band during sequential drying. Every spectral trace provided in this figure is the average of 90 spectra. The standard deviation is within 9 % of the intensity and not shown in the graph for the sake of clarity. Spectra are normalized with respect to the CH-stretch intensity that is representing the amount of protein in bone.

METHODS

2.1. Bone sample preparation

Five mature bovine femurs were obtained from a local slaughterhouse and cleaned of soft tissue. Femurs were wrapped in water soaked tissue paper, vacuum sealed into plastic bags and stored frozen at −20° C until used. Cortical bone samples were cut longitudinally from the four quadrants of the mid-diaphysis of bovine femurs using a low speed diamond blade saw (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL). Samples were then progressively polished (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL) with 600, 800, 1200 grade polishing paper and fine alumina powder (0.3 μm). Polishing and cutting debris was removed by sonication (Model 8890, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). The final dimensions of bone beams (N=30) were 30 mm in length, 3 mm in width and 1.1 mm in thickness. Samples were stored wrapped in distilled water soaked Kimwipes and stored at −20 °C. Samples were thawed completely prior to the analyses.

2.2. Biomechanical testing

The cortical bone beams were subjected to three-point bending test by TestResources Servo-All-Electric™ mechanical testing system (TestResources 800L, Shakopee, MN). The span across the support rollers for the three-point bending test was 25 mm. The rate of vertical displacement of the load point was 1 mm/second. Hydration was maintained by wrapping the samples with distilled water soaked Kimwipes except the center portion of samples and dripping distilled water on the sample during the test. All tests were performed at room temperature. The applied load and actuator displacement were recorded to construct load and displacement curves. Yield point was determined using the 0.2% offset method. These curves were then processed by using a custom Microsoft Excel macro to calculate elastic and post-yield mechanical properties: modulus of elasticity (E), maximum flexural strength (σmax), toughness and post-yield toughness (PYT). Mechanical properties were determined from each stress-strain curve (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The modulus of elasticity (E) was determined by the slope of the linear portion of the stress-strain curve (Fig. S1). Maximum flexural strength (σmax) was calculated as reported before.(4) Toughness was calculated as the total area under the stress-strain curve. PYT was reported as the area under the post-yield region of the curve.

Cortical porosity is an important factor which affects bone mechanical properties(26, 27). The effect of porosity on mechanical properties were adjusted by applying the porosity to moment of inertia ‘I’ as follows (28):

| (1) |

where p was the percentage of porosity, b was sample width and h was sample thickness. The measurement of porosity will be explained later. The porosity adjusted moment of inertia was used to calculate porosity adjusted mechanical properties which were termed as adjusted toughness, adjusted maximum flexural strength, adjusted modulus and adjusted PYT in the text. In this way, we eliminated porosity as a structural level variable to bring out effects of hydration on fabric level of mechanical integrity.

2.3. Serial dehydration and gravimetric measurement of water loss

Contributions of different water compartments were probed by a sequential dehydration process: 1) low energy dehydration at room temperature following by oven-drying at 40 °C for 48 h to remove unbound water, 2) partial replacement (e.g., loosely bound water) of remaining bound water by ethanol for 36 h, 3) removing of the remnant ethanol under vacuum for 40 h.(25) Completeness of evaporation was verified by measuring the changes in weight at 8, 24, 36, 38 and 40 h. Gravimetric measurements were performed to observe water loss by weight (Model XS64, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH).

The percent water loss was calculated as:

| (2) |

where Ww was the initial wet weight of bone and Wd was the weight after each dehydration step. In parallel with gravimetric measurements, Raman spectra of samples were collected immediately after each drying episode. The samples were kept in a sealed plastic bag except when gravimetric and Raman analyses were carried out to avoid rehydration by the moisture in air. Each sample was also weighted before and after Raman analysis. The changes between these two measurements were within 0.06%.

2.4. SWIR Raman Spectroscopy and Data processing

A refined analysis of the water in biological tissues is challenging with standard Raman systems because of protein related background fluorescence. Furthermore, the CCDs of most commercial Raman systems lack sensitivity in the OH- stretch range since the Raman scattered photons of the OH range shift deeper into the infrared region. Therefore, a custom short-wave infrared (SWIR) Raman system was built to survey the OH-stretch range while accommodating the background fluorescence. The custom SWIR system involved excitation at 847 nm (Axcel Photonics) at ~50 mW on the sample and signal collection using a shortwave InGaAs IR spectrometer (BaySpec, Inc., CA, USA) optimized for 1000-1400 nm wavenumber range that is suited for OH-stretch vibrations. The wavelength was calibrated by third order polynomial fitting using the argon source. The spectral resolution of the custom Raman system was about 9 cm−1. The numerical aperture (NA) of the objective was about 0.40.

Three Raman spectra were taken from three regions at a 100 μm spot size. Measurement locations were positioned equidistantly to cover the region of interest. Raman spectra were collected in the vicinity of the surface (~150-200 μm away from the fracture line) where tensile fracture occurred. Measurement locations were initially marked with a pencil as reference points and Raman spectra were collected from the same locations immediately after each step of dehydration episode to record the reductions in OH-band intensities. Signal collection time was set at 10 s with an accumulation of 30 scans. The Raman spectra were analyzed using OriginLab software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) to determine the position and intensity of the peaks. Briefly, the fluorescent background was removed by subtracting the fitted fluorescence baseline from the raw spectra using piecewise linear segments. No smoothing process was applied to the Raman spectra. The intensities of peaks were calculated from the fluorescent background-corrected spectra. Representative spectra for any given treatment condition were obtained by taking the average of the three spectra collected from 30 bone samples (totally 90 Raman spectra) (Fig.1). Intensity ratios (IOH/ICH) of the OH peaks from the spectra in the range of 3100-3800 cm−1 were qualified in terms of correlation with several mechanical properties of bone.

2.5. Porosity measurement

Following Raman measurements, sections were taken in a plane perpendicular to the longer axes of samples and in immediate adjacency to the fracture surface. The local cortical porosity of each sample was measured in the vicinity of the surface which experienced maximum tensile stressed and also where the failure initiated. Two digital images covering most of the surface (~ 2.5 × 1 mm) were captured (BX51, Olympus America) from each sample. The images were converted to binary form and filtered by user-defined threshold approaches using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.46r) such that a region of interest was determined and a constant threshold value was defined to identify the black pores (i.e., vascular and lacunar porosity) on the surface of the samples (4) (Fig. S2 in the supplementary material). Once defined, the same threshold was applied to all images. The total area of the pores was then normalized by the total area of the region of interest.

The local porosity was used to adjust the effect of porosity on mechanical properties to bring out effects of hydration on fabric level (i.e., porosity-independent) of mechanical integrity as discussed previously. The porosity was also used to estimate the contribution of unbound water (4) to total Raman intensity because unbound water is richly located in the microscopic pores (29) and there is about 20% unbound water contribution to the total Raman intensities of wet bone (25). Porosity adjusted Raman intensity was calculated for each biomarker as follows:

| (3) |

where Itot was total intensity and p was the percentage of the porosity. In this way, the contribution of unbound water to the total Raman intensities of wet bone was significantly eliminated in order to bring out the contribution of bound water to the total Raman intensities of wet bone.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 16 statistical software (Minitab, Inc., State College, PA). Linear regression analyses were conducted to study associations between mechanical properties and Raman OH peaks and bound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis. Non-linear regression analyses were conducted between Raman OH peaks and unbound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis. Two outlier data points were identified by large standardized residual values and these two points were eliminated from the statistical analysis, and data from the remaining n = 28 samples are presented for the correlation among gravimetric water loss, Raman biomarkers and mechanical properties. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for the resulting R2 value.

RESULTS

The results section firstly presents the associations of gravimetrically measured water content with Raman-based water measurement and porosity to show the reliability of newly proposed Raman biomarkers in quantifying different water compartments of bone. Second section of the results presents the correlations between water content (measured by gravimetric and Raman-based method) and the mechanical properties. Next, the correlations between Raman spectroscopic biomarkers and porosity adjusted mechanical properties were presented to bring out effects of hydration on bone mechanical integrity at fabric level (i.e., porosity-independent). Last, the correlations of porosity adjusted Raman intensities with the mechanical properties were presented to demonstrate that unbound water contributions to total water content in Raman intensities can be accounted for.

Reliability of newly proposed biomarkers

The presented spectra in Figure 1 were the average of three Raman spectra taken at different locations from 30 bone samples (totally 90 Raman spectra). The spectral range of 2700–3100 cm−1 manifests CH-stretch that is associated with the organic matrix (~ 90% collagen) of bone whereas the OH-stretch extends across 3100–3800 cm−1. The spectra were scaled to obtain the same intensity at the CH-stretch peak at 2949 cm−1. Therefore, changes in the Raman intensities of the each OH band were normalized by organic matrix amount (mostly collagen) which is independent of dehydration. Our results showed that there was a gradual decline in the Raman intensities of four peaks in OH-stretch band during the sequential dehydration (Fig. 1).

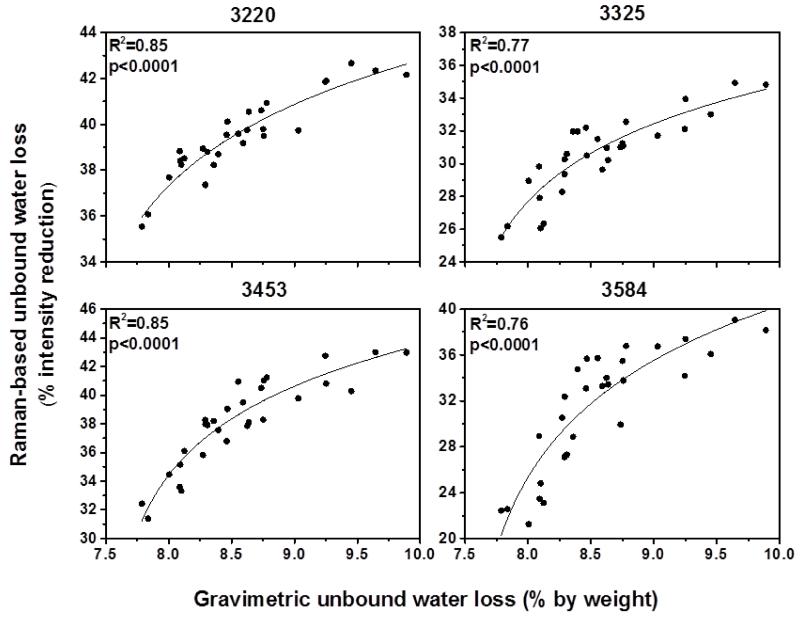

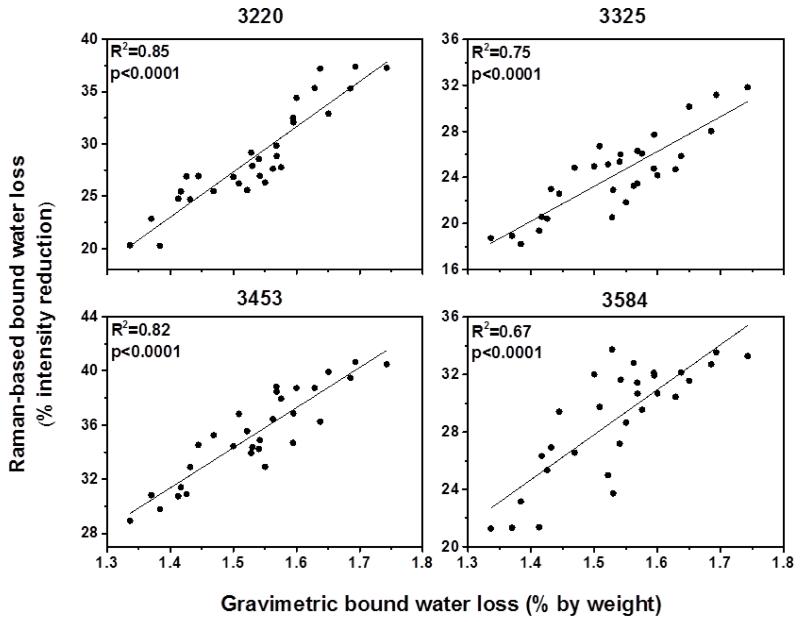

Figure 2 and 3 show the correlation between water loss measured by gravimetric analysis and Raman-based water measurement using the four peaks. The results revealed that the intensity reduction of all four peaks was correlated significantly (R2=0.66-0.85; p<0.0001) with unbound and bound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis, indicating these four peaks are highly sensitive to reflect changes in water content of bone. Especially the peaks at 3220 and 3453 cm−1 were the best (R2 =0.85 and R2=0.82, respectively) among the four peaks in terms of reflecting bound water loss in bone (Fig.3). These results emphasized that the newly proposed biomarkers obtained by using these four peaks can reliably quantify water compartments in cortical bone.

Figure 2.

Correlations between Raman-based unbound water loss and gravimetric unbound water loss. All Raman peaks significantly reflect unbound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis.

Figure 3.

Correlations between Raman-based bound water loss and gravimetric bound water loss. All Raman peaks significantly reflect bound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis.

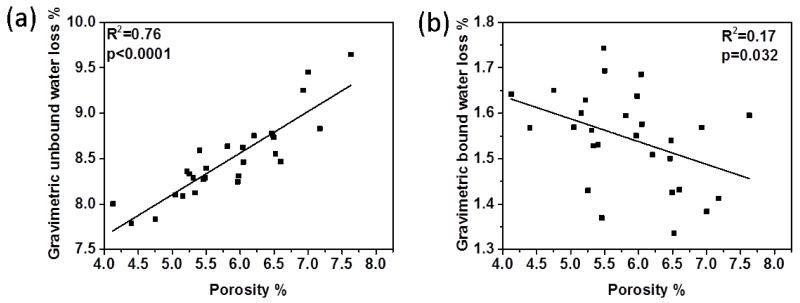

Our results showed that average porosity (i.e., vascular and lacunar void space) of 30 bone samples was equaled to 5.75±1.01%. Figure 4 shows the linear correlations of gravimetrically measured unbound and bound water with the porosity of each corresponding bone sample. The results showed that unbound water compartment was significantly correlated with porosity (Fig.4a) whereas bound water portion displayed weak inverse correlation with porosity (Fig. 4b), suggesting that measurement of porosity is a good estimation of unbound water amount.

Figure 4.

Correlations between gravimetric water loss and porosity. (a) significant inverse correlation exists between porosity and gravimetric unbound water loss, indicating porosity is a good estimate of unbound water amount in bone, (b) gravimetric bound water loss displays weak correlation with porosity.

Correlations of water compartments with the mechanical properties

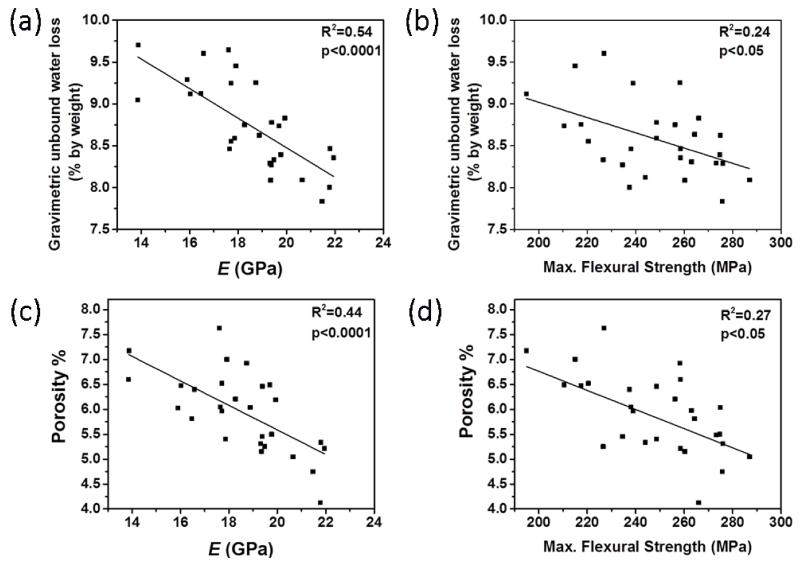

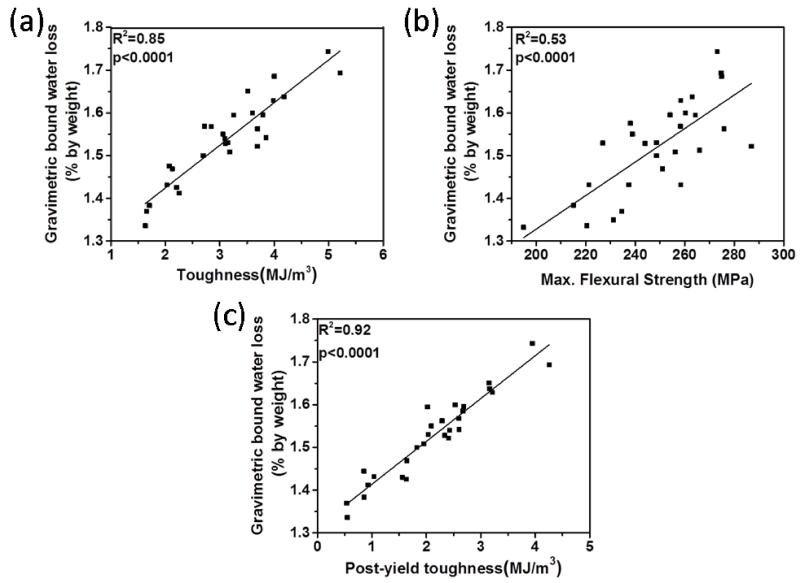

Figure 5a and 5b show that gravimetrically measured unbound water portion (8.65 ± 0.62 % by weight) of bone was negatively correlated with elastic modulus (R2=0.54, p<0.0001) and maximum flexural strength (R2=0.24, p<0.05). Such correlation also existed between porosity and same mechanical properties (i.e., elastic modulus (R2=0.44, p<0.0001) and max. flexural strength(R2=0.27, p<0.05)) (Fig. 5c and 5d). On the other hand, partial bound water portion (1.53 ± 0.09 % by weight) of bone had strong positive correlations with toughness (R2=0.85; p<0.0001), PYT (R2=0.92; p<0.0001) and maximum flexural strength (R2= 0.53; p<0.0001) (Figure 6). Gravimetrically measured total water amount was also significantly and positively correlated with toughness (R2=0.40; p<0.001) and the strength (R2=0.33; p<0.05), whereas it was inversely correlated with the modulus (R2=0.39; p<0.001) (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Correlations of unbound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis and porosity with mechanical properties. Significant inverse correlation exists between unbound water and (a) the modulus and (b) max. flexural strength as the correlation between porosity and (c) the modulus, and (d) max. flexural strength, indicating that the existing correlation of unbound water with mechanical properties may dominantly reflect the association between porosity and mechanical properties.

Figure 6.

R2 pairwise correlations between bound water loss measured by gravimetric analysis and (a) toughness, (b) max. flexural strength, and (c) PYT, indicating bound water compartments are more intimately related to post-yield mechanical properties of bone

Table 3.

The summary of regressions between MR-based water measurement and mechanical properties reported in the literature. Tabulated values are R2 values obtained by regression analysis.

| Toughness (T), Resilience (R) or Post-yield toughness (P) |

Strength or ultimate (peak) stress |

Modulus | Sample size | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gravimetric

analysis |

Total water | ~ 0.76 (T)+ | ~ 0.43+ | ~ 0.42+ | N=36 | (4) |

|

Gravimetric

analysis |

Total water | 0.40 (T) | 0.33 | −0.39 | N=28 | Present study |

| Bound water | 0.85 (T), 0.92 (P) | 0.53 | NS | |||

| Unbound water | NS | −0.24 | −0.54 | |||

|

Raman

Spectroscopy |

Collagen-bound water |

0.81 (T), 0.73 (P) | 0.51 | NS | N=28 | Present study |

| Mineral-bound water |

NS | 0.48 | −0.78 | |||

| Total water | 0.37 (T), 0.32 (P) | 0.47 | 0.48 | |||

| Collagen-bound water# |

0.52 (T), 0.44 (P) | 0.32 | NS | |||

| Mineral-bound water# |

NS | 0.50 | 0.44 | |||

| NMR | Bound water | ~ 0.40 (T) | ~ 0.36 | NS | N=18 | (6) |

| Unbound water | NS | ~ −0.21 | ~ −0.25 | |||

| NMR | Bound water | 0.57 (R) | 0.68 | 0.48 | N=40 | (9) |

| Unbound water or Lipid |

−0.49 (R) | −0.61 | −0.49 | |||

| Total water | NS | NS | NS | |||

| MRI | Bound water* | 0.30 (T) | −0.22 | NA | N=44 | (7) |

| Unbound water* |

0.17 (T) | 0.14 | NA | |||

| Total water | −0.10 (T) | 0.25 | NA | |||

mechanical properties were measured from dried bone samples.

calculated from porosity adjusted Raman intensities of wet bones.

assigned based on T2 relaxation time: Short T2= bound water, Long T2 = unbound water, NS=not significant and NA=not applicable.

Negative values indicate inverse correlation.

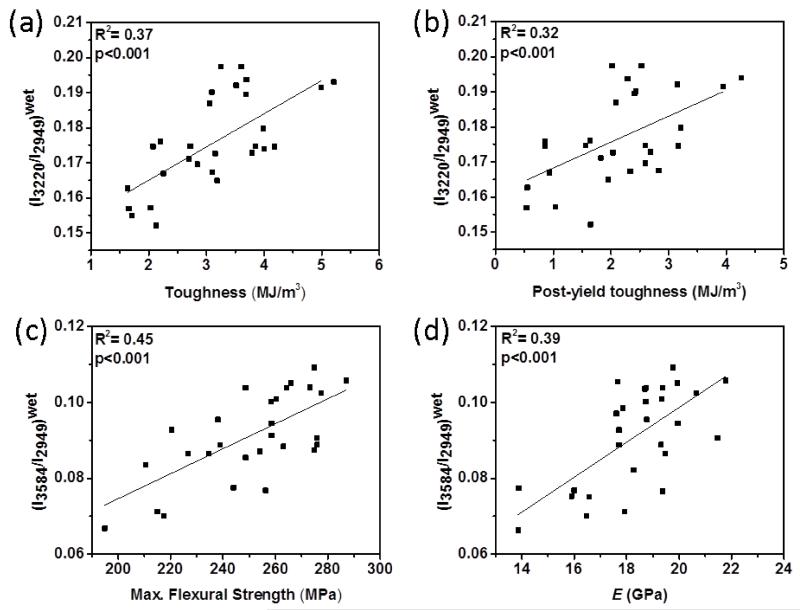

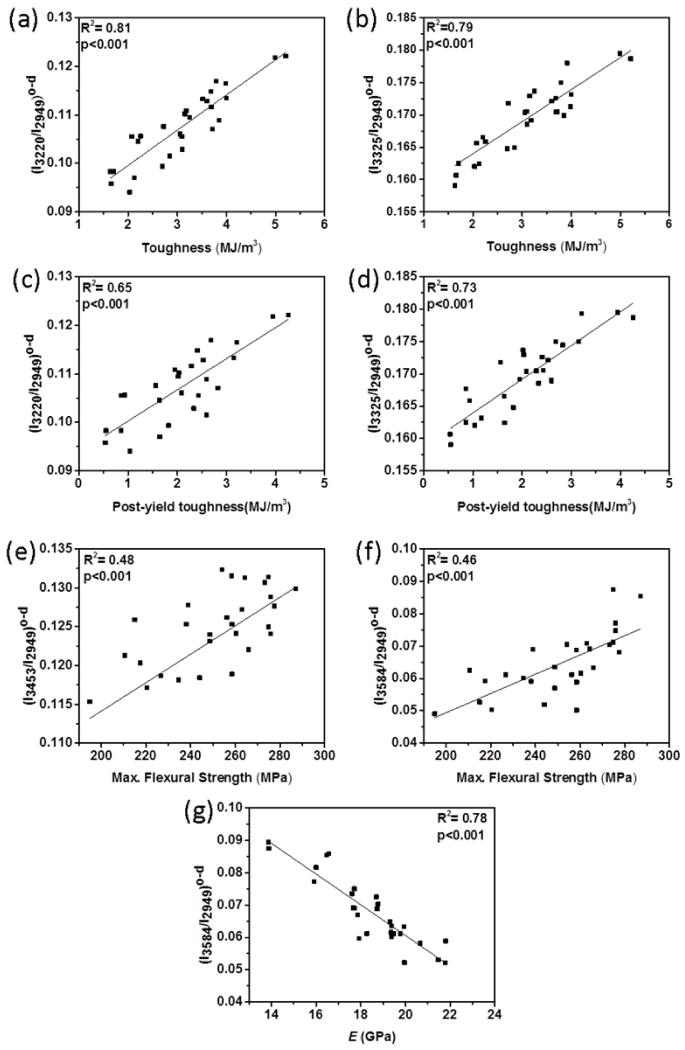

The results showed that all four spectroscopic biomarkers had different extents of correlations with mechanical properties (Table 1). The spectroscopic biomarkers related to collagen-water (I3220/I2949, I3325/I2949 and I3453/I2949) obtained from wet bone (i.e., contributions of both bound and unbound water) were significantly and positively correlated with toughness (up to R2=0.37; p < 0.001) and PYT (up to R2=0.32; p < 0.001) (Fig. 7a and 7b). The spectroscopic biomarker of mineral-water (I3584/I2949) was significantly and positively correlated with the strength (R2=0.45; p < 0.001) and the modulus (R2=0.39; p < 0.001) (Fig 4c and 4d). There was no significant correlation between toughness, PYT and mineral water-related biomarker (Table 1). Following the removal of unbound water portion by oven-drying at 40 °C, the correlations of collagen water-related biomarkers improved. Especially, I3220/I2949 and I3325/I2949 had highest positive correlation with toughness (R2=0.81 and 0.79; p<0.001, respectively) (Fig. 8a and 8b) and PYT (R2=0.65 and 0.73; p<0.001) (Fig. 8c and 8d). I3584/I2949 had highest negative correlation with elastic modulus (R2=0.78; p<0.001) and positive correlation with strength (R2=0.46; p < 0.001) (Fig. 8f, Fig. 8g and Table 1). Following the ethanol treatment for partially removing bound water, all correlations were still significant, but to a lesser extent.

Table 1.

The summary of regressions between Raman biomarkers and mechanical properties. The values inside brackets indicate the R2 values between Raman biomarkers and porosity adjusted (adj.) mechanical properties. Porosity adjusted mechanical properties improved R2 values for the strength and modulus only. Gray highlighted cells indicate p < 0.001, white cells indicate p<0.05, and blank cells are not significant, p>0.05.

| Raman Intensity Ratios | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wet bone | Oven-dried bone | Oven-dried and ethanol treated bone | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| I3220/I2949 | I3325/I2949 | I3453/I2949 | I3584/I2949 | I3220/I2949 | I3325/I2949 | I3453/I2949 | I3584/I2949 | I3220/I2949 | I3325/I2949 | I3453/I2949 | I3584/I2949 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Toughness | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.43 | ||

|

(Adj.

Toughness) |

(0.35) | (0.23) | (0.23) | (0.80) | (0.79) | (0.23) | (0.49) | (0.48) | (0.40) | (0.44) | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

Post-Yield

Toughness(PYT) |

0.32 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.47 | ||

| (Adj. PYT) | (0.30) | (0.16) | (0.18) | (0.65) | (0.73) | (0.18) | (0.44) | (0.48) | (0.40) | (0.48) | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

Elastic

modulus |

0.39 | −0.78 | ||||||||||

|

(Adj. Elastic

modulus) |

(0.48) | (−0.76) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

Max. flexural

strength |

0.23 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.15 | |||

|

(Adj. Max.

flexural strength) |

(0.25) | (0.17) | (0.21) | (0.47) | (0.39) | (0.27) | (0.51) | (0.48) | (0.14) | |||

Figure 7.

R2 pairwise correlations between mechanical properties and Raman intensity ratios obtained from wet bone samples. Significant correlations exist between (a) (I3220/I2949)wet and toughness, (b) (I3220/I2949)wet and PYT, (c) (I3584/I2949)wet and the strength, and (d) (I3584/I2949)wet and the modulus.

Figure 8.

R2 pairwise correlations between mechanical properties and Raman spectroscopic biomarkers from oven-dried bone samples. Significant correlations exist between (a) (I3220/I2949)o-d and toughness, (b) (I3325/I2949)o-d and toughness, (c) (I3220/I2949)o-d and PYT, and (d) (I3325/I2949)o-d and PYT, (e) (I3453/I2949)o-d and max. flexural strength, (f) (I3584/I2949)o-d and max. flexural strength, and (g) (I3584/I2949)o-d and the modulus.

Effects of Porosity Adjustment on the Correlations

The correlations of spectroscopic biomarkers with the adjusted (i.e., porosity-independent) mechanical properties are summarized in Table 1 (the values inside the brackets). The results showed that porosity adjustment of mechanical properties increased R2 values for the modulus markedly whereas the adjustment process slightly decreased the R2 values for toughness and PYT in wet condition, indicating the modulus is more sensitive to porosity than toughness and PYT (Table 1). Also, the results suggested that different water compartments in bone determined by these new biomarkers are important determinants of bone mechanical properties independently of porosity.

Correlations of adjusted spectroscopic biomarkers with the mechanical properties

Raman intensity of wet bone is mostly contributed by bound water (up to ~72% of total intensity) and unbound water (~20%) compartments.(25) Therefore, the isolation of unbound water from the total Raman intensities of wet bone is required to obtain better correlations between the Raman biomarkers of wet bone and the mechanical properties. Since porosity is directly proportional to amount of unbound water (Fig. 4a), the contribution of unbound water can be eliminated from the total Raman intensity to a significant extent by using porosity adjustment approach. Figure S3 (in supplementary material) shows the correlation between porosity adjusted Raman intensity obtained from wet bone (Iadj) and the Raman intensities obtained from oven-dried bone samples (Io-d) (i.e., predominantly bound water intensities)(25). The porosity adjusted biomarkers were significantly correlated with the biomarkers of oven-dried bone samples, suggesting that porosity adjustment approach can eliminate the unbound water’s contribution into the total intensity to a great extent. The results measured from wet bones also suggest that the contribution of unbound water compartment to the peak at 3584 cm−1 is limited due to the lack of high correlation between Iadj3584 and Io-d3584 (Fig. S3)

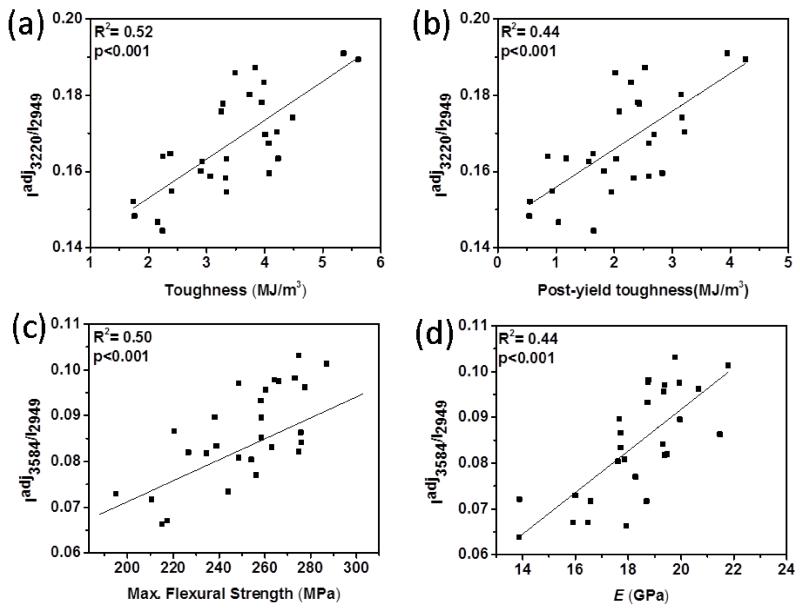

Adjustment of the spectroscopic biomarkers of wet bone by porosity also improved their correlations to the mechanical properties as summarized in Table 2. Especially, Iadj3220/I2949 was significantly correlated with toughness (R2=0.52; p<0.001) and PYT (R2=0.44; p<0.001) (Fig. 9a-b) whereas Iadj3584/I2949 was significantly correlated with the strength (R2=0.50; p<0.001) and the modulus (R2=0.44; p<0.001) of wet bone (Fig. 9c-d).

Table 2.

The summary of regressions between mechanical properties and porosity adjusted Raman biomarkers. Gray highlighted cells indicate p < 0.001, white cells indicate p<0.05, blank cells are not significant, p>0.05.

| Raman Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity Adjusted Raman Intensity of Wet Bone | ||||

|

| ||||

| Iadj3220/I2949 | Iadj3325/I2949 | Iadj3453/I2949 | Iadj3584/I2949 | |

|

| ||||

| Toughness | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.27 | |

|

| ||||

| Post-yield toughness | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.22 | |

|

| ||||

| Elastic modulus | 0.44 | |||

|

| ||||

| Max. flexural strength | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

Figure 9.

R2 pairwise correlations between mechanical properties and porosity adj. Raman spectroscopic biomarkers. Significant correlations exist between (a) Iadj3220/I2949 and the toughness, (b) Iadj3220/I2949 and PYT, (c) Iadj3584/I2949 and the strength, and (d) Iadj3584/I2949 and the modulus.

DISCUSSION

Decades of studies showed that dehydration increases the stiffness (23, 24, 30-34), tensile strength (24, 30, 31), and hardness of bone (30, 31, 34) while decreasing the strain at fracture (30, 31) and energy to fracture (i.e., toughness).(31, 32) However, the effects of hydration in these studies were considered as changes in total amount of water content in bone without differentiating the effects of bound and unbound water (6, 12, 13, 15). While MR has been useful in measuring unbound and bound water compartments, SWIR Raman spectroscopy is the only published method (25) thus far which is able to classify bound water further to the moieties that water molecules are attached to (i.e. mineral vs. collagen). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first thorough study to investigate association between different water compartments in bone and bone’s mechanical properties.

Previously, Nyman et al. (4) showed that gravimetrically measured total water loss was significantly correlated with toughness, strength and stiffness. In their study, samples were dehydrated (at 21, 50, 70 and 110° C), and then the mechanical properties of control and dried bone samples at different temperature were measured. They found a significant correlation between total water loss and the mechanical properties of dehydrated bone without distinguishing between bound and unbound water compartments in these correlations (Table 3). The correlations of total water loss with the mechanical properties in the current study were slightly different than that of the previous study (4) (Table 3). For example, unlike the previous study, the correlation between total water loss and toughness was moderate in the current study (Table 3). This difference may emerge from the methodology of the previous study(4) that the mechanical properties were measured from dehydrated bone samples. In the previous study, the samples were dried at higher temperature (i.e., 70 and 110°C) which may have denatured collagen that significantly affects toughness of bone (35). Therefore, the displayed high correlation may not have solely emerged from total water loss and may also reflect collagen quality. In the current study, the mechanical properties were measured from wet bone samples followed by a sequential dehydration process to distinguish between correlation of bound and unbound water with the mechanical properties. In this manner, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first gravimetric evidence for association of bound and unbound water compartments in bone with mechanical properties of wet bone. The overall gravimetric results herein showed that greater amount of bound water indicates increased toughness (Fig. 6a-c) and strength (Fig. 6b) whereas greater amount of unbound water indicates decreased elastic modulus and strength (Fig. 5a-b). The moderate correlation between unbound water and mechanical properties (Fig. 5a-b) may emerge from the porosity because the existing correlations of unbound water with mechanical properties were similar to that of the porosity (Fig. 5c and 5d) and unbound water amount is closely associated with the porosity (Fig.4a). Thus, the existing moderate correlation may dominantly reflect the association between porosity and mechanical properties as porosity effects the modulus and the strength (Fig. 5c and 5d), indicating unbound water is a surrogate measure of porosity as discussed elsewhere (29). On the other hand, the correlation between bound water and porosity was weak (R2=0.17, p=0.032) (Fig. 4b), indicating bound water is not associated with porosity strongly. Furthermore, bound water displayed strong correlation with post-yield mechanical properties (Fig. 6). Therefore, the overall results suggested that bound water compartments are more intimately related to post-yield mechanical properties of bone, whereas unbound water compartment is related to elastic properties of bone (Fig. 5 and 6).

MR-derived water content measurements are correlated with mechanical properties to varying degrees (Table 3). In this study, we showed that Raman-based water content measurement using the novel spectroscopic biomarkers from oven-dried bone samples robustly reflects the significant correlations between bound water and the mechanical properties (e.g., R2=0.81 for toughness) (Fig. 8 and Table 1). Furthermore, these correlations of the biomarkers for wet bone samples are comparable with that of the MR-derived water content (Table 3). Therefore, Raman-based water measurement offers an alternative method to study different water compartments in bone, and uniquely allows classification of bound water to the moieties that water molecules are attached to (i.e. mineral vs. collagen).

The overall results of Raman analyses showed that the bound water layer that was partially removed by ethanol treatment appears to be critical for bone mechanics since R2 values between mechanical properties and the Raman biomarkers mostly peaked after oven dried and decreased after ethanol treatment (Table1). Previous studies showed that water in bone interacts with collagen at two different levels: (i) hydrogen bonding on collagen molecules due to hydroxyl group of hydroxyproline (Hyp), and (ii) hydrogen bonding between collagen fibrils due to polar side chains (hydrophilic residues) of collagen.(36-38) In fact, it was previously reported that five different water regimes were observed around collagen structure in which characterized by increasing water concentration, reportedly ranging from 0–0.010 g/g (regime I) to > 0.5 g/g (regime V).(36) In agreement with previous studies, we identified three bound water compartments around collagen in our previous study (25) as shown by three different peaks (3220, 3325 and 3453 cm−1) in the OH-stretch band (Fig.1). Among these three peaks, the shoulder at 3220 cm−1 seems to be associated with loosely bound water or physically more accessible bound water due to the its quick replacement by D20.(25) Our result herein showed that this peak exhibited the highest correlation with toughness of both wet and oven-dried bone samples (Fig 7a and Fig 8a). Therefore, the results indicated that the loosely bound or physically more accessible bound water layer around the collagen appears to be more intimately associated with toughness.

It was observed that the collagen-water related biomarkers have different degrees of correlations with different mechanical properties of bone (Table 1). For example, collagen-water related biomarkers ((I3220/I2949)o-d and (I3325/I2949)o-d) had stronger correlation with toughness and PYT (Fig.8) than strength (Table 1); and they had no significant association with modulus (Table 1). Therefore, our results corroborate the notion that collagen of bone determines the ductility and post-yield regime of bone.(35, 39) (Fig 8) Another wide-spread notion is that mineral contributes to stiffness and strength predominantly.(40, 41) While this notion is well-supported, our results also show that all of the three collagen-related biomarkers display low-moderate significant correlations with strength (R2=0.23 for wet bone and R2=0.48 for oven-dried bone) (Table 1), suggesting that collagen-bound water and collagen itself also significantly contribute the strength of bone along with toughness. Especially, the biomarker of (I3453/I2949)o-d resulting from the peak at 3453 cm−1 of oven-dried bone samples significantly correlated (R2=0.48) with the strength which is almost comparable with that of the mineral-related biomarker of (I3584/I2949)o-d (Fig 8e and 8f).

Previous SWIR Raman analysis and molecular dynamics simulations from our group showed that the peak at 3453 cm−1 is associated with hydroxyproline (Hyp) and water bound to Hyp.(25) Significant correlations between this peak intensity and strength support the vital role of Hyp plays by binding water molecules as a sheath around the collagen molecule.(42) Taking all into consideration, our results suggest that greater amount of bound water around collagen with the involvement of Hyp may provide greater stabilization of the collagen network, increasing bone strength.

The previous studies using gravimetric or MR-based techniques have only shown an evidence for association of either total amount of water or total amount of unbound or bound water with mechanical properties.(5-7, 9) (Table 3) However, this decade of studies have supported the notion that mineral-bound water and collagen-bound water compartments may contribute to mechanical integrity of bone together (43, 44) or independently each other.(8, 42, 45-48) Especially, it was indicated in previous studies that water bound to mineral and structural water in mineral crystals may affect bone mechanical integrity (12, 45, 47, 49) independently of collagen. The previous studies showed that there are at least two different water compartments in and around bone mineral crystallites with the existence of the structural OH content in bone mineral.(12, 15, 50, 51) First water compartment is strongly bound to the surface of bone mineral and surrounds the crystal as a hydration layer.(12, 15) This hydrated layer creates an environment which exchanges ions with the stable apatitic core during the growth of bone mineral. Therefore, the hydrated layer decreases as a result of mineral maturation.(52-54) More recently, it was also found that the hydration layer mediates the orientation of mineral crystals along the c-axis direction (collagen fibrils direction).(45) Second water compartment is the crystal-structural water (49, 55, 56) located in the mineral lattice that provides local structural stability through creating hydrogen bonding bridges between surrounding ions (12, 56, 57). This tightly bound water cannot be removed even with drying at 100 °C. (50, 51) However, to date, there is no evidence for association between mineral-related water in bone and bone mechanical properties. In this perspective, the biomarker of I3584/I2949 provides unique information about the status of mineral-related water to study on its possible contribution to bone mechanics since it is known that stiffness and strength of bone are predominantly associated with mineral moiety of bone.(40, 41) In agreement, our results herein showed that (I3584/I2949)o-d had a strong positive correlation with the strength (R2=0.46) (Fig 8f) and strong negative correlation with the modulus (R2= 0.78) (Fig 8g). This strong negative correlation between mineral-bound water and the modulus suggested that the lower amount of bound water indicated increased modulus (or stiffness). This outcome can be explained by earlier reports that bound water around the mineral crystals decreases as a result of mineral maturation.(52, 53) Taking all into consideration, the results suggest that lesser amount of bound water may indicate matured mineral crystals and matured mineral crystals in bone may provide greater the modulus to bone. Overall, our results revealed the first evidence between mineral-bound water and modulus (stiffness). Furthermore, we also found a strong correlation between mineral-bound water and the strength for wet and oven-dried bone samples and this correlation was decreased after ethanol treatment, indicating that bound water around mineral may also contribute to bone strength (Table 1).

Cortical porosity is one of the major structural variables that affects bone mechanical properties (26, 27) and its effects must be eliminated in order to bring out the effects of hydration on bone mechanical integrity at fabric level (i.e., porosity-independent). Thus, we adjusted the effects of porosity on the mechanical properties by using local porosity measured at the failure region of the tensile face of the bone samples(58). Such local porosity is more relevant to mechanical properties under three-point bending test. After adjustment of mechanical properties by porosity, we observed improved R2 values for the modulus and strength whereas we only observed slightly decreased R2 values for toughness and PYT (Table 1 values inside the brackets). Therefore, water in bone is one of the important determinants of bone mechanical integrity independently of porosity. Porosity is also directly proportional to the amount of unbound water (Fig. 4a). Because Raman intensities of wet bone is confounded by unbound water, the contribution of unbound water to Raman intensity can be adjusted by using porosity, bringing out the contribution of bound water in total water intensity. For instance, the coefficient of determination for the regression of between the Raman biomarker of I3220/I2949 and toughness improves to 0.52 from 0.37 after the porosity adjustment of wet bone’s Raman intensity (Fig. 9, Table 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, adjustment of Raman intensities of OH-peaks by porosity showed significant correlations with the intensities of oven-dried bone samples (Fig. S3), indicating measurement of bound water contribution in wet bone can be improved by porosity adjustment approach.

In the long term, Raman-based water measurement can potentially provide fracture risk assessment in vivo as the recent advances in spatially offset Raman spectroscopy (SORS) (59) and the Raman tomography.(60, 61) One limitation of Raman-based water measurement in vivo is that there is no Raman band that exclusively reflects bound water. However, our previous work (25) revealed that the intensity of sub-bands at wet bone spectra is dominated by bound water (~72% of total intensity) and we showed herein that the Raman biomarkers obtained from wet bone samples without any porosity adjustment was readily correlated to the mechanical properties significantly (Fig. 7 and Table 1) and these biomarkers can be further adjusted by porosity (for instance measured by high resolution peripheral computed tomography-pQCT in vivo), to improve the measurement of bound water in wet bone (Fig. 9 and Table 2) as we elucidated in the previous paragraph. Therefore, these new bone quality biomarkers hold potential for assessing bone quality nondestructively and noninvasively in vivo.

The relationships between the mechanical properties and water compartments can be summarized as follows: Unbound water is inversely associated with elastic modulus and the strength as the porosity’s correlation with the same mechanical properties (Fig. 5) and unbound water amount is significantly correlated with porosity (Fig. 4a), suggesting that unbound water measurement is a surrogate measure of porosity. Greater amount of collagen-bound water indicates an increase in bone toughness and post-yield toughness, indicating collagen-bound water is predominantly associated with post-yield mechanical properties of bone. Collagen-bound water also contributes bone strength in a way that may stabilize collagen mechanical integrity, but collagen-bound water is not associated with elastic modulus of bone (i.e., stiffness). On the other hand, mineral-bound water is predominantly associated with bone strength and the modulus. Especially, mineral-bound water is inversely associated with the modulus and may reflect maturation of bone mineral crystals. Since bound-water is associated with multiple factors (e.g., mineralization, collagen crosslinks, collagen quality, non-collagenous proteins and porosity) which are all interrelated (29), this may be elucidation of high correlation of bound water compartments with multiple mechanical properties. Cumulatively, for the first time, we showed an evidence for contribution of different water compartments in bone to mechanical properties of wet bone.

There are several limitations of the current study. In this study, the porosity was measured locally from the region where the failure occurred (Fig. S2). Since local porosity determines the failure process, it is more relevant to mechanical properties. However, optical microscopy-based local porosity measurement (accounting for vascular and lacunar porosity) may not totally reflect gravimetrically measured unbound water content because the unbound water content emerged from the entire volume of bone including porosity of canalicular network (~1% of bone volume (62)). This may be partially explanation of why we observed 76% R2 value for the correlation between local porosity and gravimetrically measured unbound water content instead of 90% or greater. In this context, micro-CT based measurement of porosity over bone’s volume may have been more accurate. Nonetheless, the association between local porosity and gravimetrically measured unbound water content was acceptably high at R2 = 0.76. Second, we have not measured the degree of mineralization as an additional variable to predict mechanical properties in the current study. However, the literature has shown that the mineral phase is predominantly associated with the elastic properties of bone (27, 40, 41, 63) which unfortunately does not accurately correlate with the fracture risk (2, 3). After decades of work, the focus has shifted to the post-yield region (35, 38, 64) as the determinants of skeletal fragility at the fabric level and mineral content does not play a role in the post-yield region (35, 41, 64). Furthermore, last decade of studies showed that bound water can be predictive of post-yield mechanical properties of bone (4-7). It is possible that adding mineral content as a second variable to the bound water may increase the predictive power; however, we expect this to be marginal in the light of the literature. Third, bone is compositionally and morphologically heterogeneous (41). The Raman-derived water content in the current study was measured locally where the failure occurred. Therefore, it may be better to investigate entire bone surface such as using Raman mapping to bring out possible fluctuations of water content. Using these new biomarkers, further research is needed to quantitatively evaluate possible differences in water distribution over bone’s surface. Nevertheless, the reported correlations in the current study between Raman-based water measurements from the local region and mechanical properties were acceptably high (e.g., R2 = 0.81 for toughness) (Table 1). Last, the Raman peaks of 3220, 3325 and 3453 cm−1 do not exclusively reflect collagen-related water. Non-collagenous proteins also contribute to the intensity of these peaks. However, we expect this contribution to be limited because the organic matrix of bone contains mostly collagen type I (90% of organic matrix).(35, 38) Since the organic matrix is dominated by the collagen that is a good source to provide binding site for water as we discussed in the text, it is logical to think that organic-bound matrix water is also predominated by the collagen-bound water. Therefore, the term of “collagen-bound water” accounts for mostly water bound to collagen along with the contribution of water bound to non-collagenous proteins.

In conclusion, the reported correlations of new spectroscopic biomarkers to bone mechanical properties underline the necessity for enabling approaches to assess these new bone quality biomarkers noninvasively in vivo to improve the current diagnosis of those who may be at risk of bone fracture due to aging and diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Using novel spectroscopic biomarkers, we investigated associations of different water compartments in bone to elastic and post-yield mechanical properties of cortical bone.

Greater amount of collagen-bound water indicates an increase in bone toughness and post-yield toughness.

Collagen-bound water is not associated with the elastic modulus of bone.

Greater amount of mineral-bound water indicates an increase in bone strength and mineral-bound water is inversely associated with the elastic modulus.

These new bone quality biomarkers hold potential for assessing bone quality in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is partially supported by the George W. Codrington Charitable Foundation Student Research Fund by means of think [box] at CWRU and the research grant R01AR057812 (OA) from the NIAMS institute of NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank to Shan Yang and Bolan Li for their valuable help to set up our customized SWIR Raman system and thank Cedric Hansen for his help in preparing bone samples. We also thank to the Republic of Turkey, Ministry of National Education (M.E.B) for the scholarship of Mustafa Unal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and Economic Burden of Osteoporosis-Related Fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22(3):465–75. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV. Assessment of fracture risk. European journal of radiology. 2009;71(3):392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.061. Epub 2009/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuit S, Van der Klift M, Weel A, De Laet C, Burger H, Seeman E, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34(1):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyman JS, Roy A, Shen X, Acuna RL, Tyler JH, Wang X. The influence of water removal on the strength and toughness of cortical bone. Journal of biomechanics. 2006;39(5):931–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.01.012. Epub 2006/02/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyman JS, Gorochow LE, Adam Horch R, Uppuganti S, Zein-Sabatto A, Manhard MK, et al. Partial removal of pore and loosely bound water by low-energy drying decreases cortical bone toughness in young and old donors. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2013;22:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.08.013. Epub 2013/05/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyman JS, Ni QW, Nicolella DP, Wang XD. Measurements of mobile and bound water by nuclear magnetic resonance correlate with mechanical properties of bone. Bone. 2008;42(1):193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae WC, Chen PC, Chung CB, Masuda K, D’Lima D, Du J. Quantitative ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI of human cortical bone: correlation with porosity and biomechanical properties. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(4):848–57. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Seara MA, Wehrli SL, Takahashi M, Wehrli FW. Water Content Measured by Proton-Deuteron Exchange NMR Predicts Bone Mineral Density and Mechanical Properties. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(2):289–96. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horch RA, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. Non-invasive predictors of human cortical bone mechanical properties: T2-discriminated 1H NMR compared with high resolution X-ray. PloS one. 2011;6(1):e16359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller KH, Trias A, Ray RD. Bone Density and Composition age-related and pathological changes in water and mineral content. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1966;48(1):140–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson RA, Elliot SR. The Water Content of Bone I. The Mass of Water, Inorganic Crystals, Organic Matrin, and CO2 Space Components in a Unit Volume of Dog Bone. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1957;39(1):167–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson EE, Awonusi A, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Tecklenburg MMJ, Beck LW. Three structural roles for water in bone observed by solid-state NMR. Biophys J. 2006;90(10):3722–31. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarev YA, Grishkovsky BA, Khromova TB, Lazareva AA, Grechishko VS. Bound water in the collagen-like triple-helical structure. Biopolymers. 1992;32(2):189–95. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horch RA, Nyman JS, Gochberg DF, Dortch RD, Does MD. Characterization of 1H NMR signal in human cortical bone for magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;64(3):680–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22459. Epub 2010/09/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson EE, Awonusi A, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Tecklenburg MM, Beck LW. Highly ordered interstitial water observed in bone by nuclear magnetic resonance. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20(4):625–34. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz E, Chung CB, Bae WC, Statum S, Znamirowski R, Bydder GM, et al. Ultrashort echo time spectroscopic imaging (UTESI): an efficient method for quantifying bound and free water. NMR in biomedicine. 2012;25(1):161–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswas R, Bae W, Diaz E, Masuda K, Chung CB, Bydder GM, et al. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) imaging with bi-component analysis: bound and free water evaluation of bovine cortical bone subject to sequential drying. Bone. 2012;50(3):749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson RA. Bone tissue: composition and function. The Johns Hopkins Medical Journal. 1979;145(1):10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranta H, Strömberg L. Growth changes of collagen cross-linking, calcium, and water content in bone. Archives of orthopaedic and traumatic surgery. 1985;104(2):89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00454244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeni YN, Brown CU, Norman TL. Influence of Bone Composition and Apparent Density on Fracture Toughness of the Human Femur and Tibia. Bone. 1998;22(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Ackerman JL, Chesler DA, Graham L, Wang Y, Glimcher MJ. Density of organic matrix of native mineralized bone measured by water-and fat-suppressed proton projection MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2003;50(1):59–68. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao H, Nazarian A, Ackerman JL, Snyder BD, Rosenberg AE, Nazarian RM, et al. Quantitative<sup> 31</sup> P NMR spectroscopy and< sup> 1</sup> H MRI measurements of bone mineral and matrix density differentiate metabolic bone diseases in rat models. Bone. 2010;46(6):1582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans FG. Mechanical properties of bone. Thomas Springfield; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dempster WT, Liddicoat RT. Compact bone as a non-isotropic material. American Journal of Anatomy. 1952;91(3):331–62. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000910302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unal M, Yang S, Akkus O. Molecular spectroscopic identification of the water compartments in bone. Bone. 2014;67:228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCalden R, McGeough J, Barker M. Age-related changes in the tensile properties of cortical bone. The relative importance of changes in porosity, mineralization, and microstructure. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1993;75(8):1193–205. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currey JD. The effect of porosity and mineral content on the Young’s modulus of elasticity of compact bone. Journal of biomechanics. 1988;21(2):131–9. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee PS, Lee J, Shin N, Lee KH, Lee D, Jeon S, et al. Microcantilevers with nanochannels. Advanced Materials. 2008;20(9):1732–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granke M, Does MD, Nyman JS. The Role of Water Compartments in the Material Properties of Cortical Bone. Calcified Tissue Int. 2015:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-9977-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada H, Evans FG. Strength of biological materials. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans FG, Lebow M. Regional differences in some of the physical properties of the human femur. Journal of applied physiology. 1951;3(9):563–72. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1951.3.9.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedlin ED, Hirsch C. Factors affecting the determination of the physical properties of femoral cortical bone. Acta Orthopaedica. 1966;37(1):29–48. doi: 10.3109/17453676608989401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith J, Walmsley R. Factors affecting the elasticity of bone. Journal of anatomy. 1959;93(Pt 4):503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rho J-Y, Pharr GM. Effects of drying on the mechanical properties of bovine femur measured by nanoindentation. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 1999;10(8):485–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008901109705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Bank RA, TeKoppele JM, Agrawal C. The role of collagen in determining bone mechanical properties. Journal of orthopaedic research. 2001;19(6):1021–6. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pineri M, Escoubes M, Roche G. Water–collagen interactions: calorimetric and mechanical experiments. Biopolymers. 1978;17(12):2799–815. doi: 10.1002/bip.1978.360171205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nomura S, Hiltner A, Lando J, Baer E. Interaction of water with native collagen. Biopolymers. 1977;16(2):231–46. doi: 10.1002/bip.1977.360160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyman JS, Reyes M, Wang X. Effect of ultrastructural changes on the toughness of bone. Micron. 2005;36(7):566–82. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burstein AH, Zika J, Heiple K, Klein L. Contribution of collagen and mineral to the elastic-plastic properties of bone. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1975;57(7):956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singer K, Edmondston S, Day R, Breidahl P, Price R. Prediction of thoracic and lumbar vertebral body compressive strength: correlations with bone mineral density and vertebral region. Bone. 1995;17(2):167–74. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(95)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rho J-Y, Kuhn-Spearing L, Zioupos P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med Eng Phys. 1998;20(2):92–102. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bella J, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Hydration Structure of a Collagen Peptide. Structure. 1995;3(9):893–906. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rai RK, Sinha N. Dehydration-Induced structural changes in the collagen–hydroxyapatite interface in bone by high-resolution solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2011;115(29):14219–27. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samuel J, Sinha D, Zhao JC-G, Wang X. Water residing in small ultrastructural spaces plays a critical role in the mechanical behavior of bone. Bone. 2014;59:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Von Euw S, Fernandes FM, Cassaignon S, Selmane M, Laurent G, et al. Water-mediated structuring of bone apatite. Nature materials. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nmat3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masic A, Bertinetti L, Schuetz R, Chang S-W, Metzger TH, Buehler MJ, et al. Osmotic pressure induced tensile forces in tendon collagen. Nature Communications. 2015:6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davies E, Müller KH, Wong WC, Pickard CJ, Reid DG, Skepper JN, et al. Citrate bridges between mineral platelets in bone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(14):E1354–E63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315080111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pálfi VK, Perczel A. Stability of the hydration layer of tropocollagen: A QM study. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31(4):764–77. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pasteris JD, Yoder CH, Wopenka B. Molecular water in nominally unhydrated carbonated hydroxylapatite: The key to a better understanding of bone mineral. American Mineralogist. 2014;99(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson R. Chemical analysis and electron microscopy of bone. Bone as a Tissue. 1960:186–250. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoder CH, Pasteris JD, Worcester KN, Schermerhorn DV. Structural water in carbonated hydroxylapatite and fluorapatite: Confirmation by solid state 2H NMR. Calcified Tissue Int. 2012;90(1):60–7. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cazalbou S, Combes C, Eichert D, Rey C, Glimcher MJ. Poorly crystalline apatites: evolution and maturation in vitro and in vivo. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2004;22(4):310–7. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0488-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rey C, Combes C, Drouet C, Glimcher MJ. Bone mineral: update on chemical composition and structure. Osteoporosis Int. 2009;20(6):1013–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0860-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farlay D, Panczer G, Rey C, Delmas PD, Boivin G. Mineral maturity and crystallinity index are distinct characteristics of bone mineral. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2010;28(4):433–45. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wehrli FW, Fernández-Seara MA. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of bone water. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2005;33(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neuman W, Toribara T, Mulryan B. The Surface Chemistry of Bone. VII. The Hydration Shell1. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1953;75(17):4239–42. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marino AA, Becker RO, Bachman CH. Dielectric determination of bound water of bone. Physics in medicine and biology. 1967;12(3):367. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/12/3/309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cowin SC. Bone mechanics handbook. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matousek P, Draper ER, Goodship AE, Clark IP, Ronayne KL, Parker AW. Noninvasive Raman spectroscopy of human tissue in vivo. Applied spectroscopy. 2006;60(7):758–63. doi: 10.1366/000370206777886955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Esmonde-White FW, Esmonde-White KA, Kole MR, Goldstein SA, Roessler BJ, Morris MD. Biomedical tissue phantoms with controlled geometric and optical properties for Raman spectroscopy and tomography. Analyst. 2011;136(21):4437–46. doi: 10.1039/c1an15429j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Demers J-LH, Davis SC, Pogue BW, Morris MD. Multichannel diffuse optical Raman tomography for bone characterization in vivo: a phantom study. Biomedical optics express. 2012;3(9):2299–305. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.002299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin RB. Porosity and specific surface of bone. Critical reviews in biomedical engineering. 1983;10(3):179–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akkus O, Adar F, Schaffler MB. Age-related changes in physicochemical properties of mineral crystals are related to impaired mechanical function of cortical bone. Bone. 2004;34(3):443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garnero P. The Role of Collagen Organization on the Properties of Bone. Calcified Tissue Int. 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-9996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.