Abstract

The recessive wellhaarig (we) mutations, named for the wavy coat and curly whiskers they generate in homozygotes, have previously been mapped on mouse Chromosome 2. To further limit the possible location of the we locus, we crossed hybrid (C57BL/6 x AKR)F1, we4J/+ females with AKR, we4J/we4J mutant males to create a large backcross family that was typed for various microsatellite markers and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that distinguish strains AKR and B6. This analysis restricted the location of we4J between sites that flank only one gene known to be expressed in skin: epidermal-type transglutaminase 3 (Tgm3). To test Tgm3 as a candidate for the basis of the wellhaarig phenotype we took two approaches. First, we sequenced all Tgm3 coding regions in mice homozygous for four independent, naturally-occurring wellhaarig alleles (we, weBkr, we3J and we4J) and found distinct defects in three of these mutants. Second, we crossed mice homozygous for an induced mutant allele of Tgm3 (Tgm3Btlr) with mice heterozygous for one of the wellhaarig alleles we possess (we4J or weBkr) to test for complementation. Because the progeny inheriting both a recessive we allele and a recessive Tgm3Btlr allele displayed wavy hair, we conclude that the classic wellhaarig mutations result from defects in Tgm3.

Keywords: Positional candidate approach, Complementation testing, Intraspecific backcross mapping, Hair morphology

1. Introduction

The recessive wellhaarig mutations in mice (abbreviated we) generate curly vibrissae and a first hair-coat with a striking wavy texture (see Figure 1). The original we variant arose as a spontaneous mutation in the stocks of Agnes Bluhm (1862–1943, a physician and researcher at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute, Berlin, Germany) but wellhaarig’s description and assignment to Linkage group V were first reported by Peter Hertwig [1] who obtained the inbred line from Bluhm in 1936. This original mutation has been joined by the “wellhaarig; Bunker” allele (weBkr, named for its discoverer, Helen P. Bunker), which spontaneously arose at The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) in 1964 and was later shown not to complement we [2]. Two more spontaneous remutations were subsequently discovered (also at The Jackson Laboratory), “wellhaarig; wellhaarig 3 Jackson” (we3J)[3] and “wellhaarig; wellhaarig 4 Jackson” (we4J)[4], although the we3J variant is no longer extant. While we was used extensively as a phenotypic marker in early mapping studies of Linkage Group V [5,6], its position on the physical map of Chromosome (Chr) 2 is not well defined and its molecular basis has not been determined.

Figure 1.

The classic wellhaarig phenotype. 16-day-old siblings are shown. The mouse on the left is a we4J/we4J mutant, the mouse on the right is a +/we4J heterozygote.

In order to assign the mutant wellhaarig phenotype to a specific genetic cause, we have fine-mapped the we4J mutation with respect to various microsatellite and single-nucleotide polymorphisms on mouse Chr 2. This analysis has identified a small number of co-localizing candidate genes, one of which has been found to harbor distinct mutations in we, weBkr and we4J mutant mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

All animals were housed and fed according to Federal guidelines, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at CCSU approved of all procedures involving mice. Mice from the standard inbred strain C57BL/6J (Jax Stock Number 664), inbred AKR/J-we4J/J mice (Jax Stock Number 3656, homozygous we4J), and B10.129-weBkr/CyJ mice (Jax Stock Number 475, homozygous for weBkr) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Inbred C57BL/6J-Tgm3m2Btlr/Mmmh mice, carrying the “tortellini” mutation, an EtNU-induced point mutation in the Tgm3 gene produced by Bruce Beutler and colleagues [7] (herein designated Tgm3Btlr), were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center at the University of Missouri (Columbia, MO USA). The Tgm3Btlr mutation is a G to A transition at position 2:130024585 that destroys the splice donor site at the 5’ end of Intron 3–4, and is predicted by Won, Moresco and Buetler [7] to cause the splicing of Exon 2 with Exon 4, eliminating the 80 amino acids (61–140) encoded by Exon 3. These wellhaarig and tortelinni mutants were reliably identified by the presence of curly vibrissae that appear shortly after birth, and persist throughout the life span. The first coat of hair in these mutants also grows in with a wavy texture that is most striking at about 10 days to 3 weeks of age (see Figure 1 for a we4J/we4J mutant), but becomes less marked in subsequent hair coats.

2.2. DNA analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from 2 mm tail-tip biopsies taken from two to three-week-old mice using Nucleospin® Tissue kits distributed by Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Mountain View, CA, USA), as directed. DNA samples from standard inbred strains that we do not routinely maintain in our colony—including NX129-10/Ty-we3J (homozygous for we3J), which are no longer extant—were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory’s Mouse DNA Resource before it ceased operations in December 2013.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in 13 ul reactions using the Titanium PCR kit from Clontech Laboratories, as directed. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were designed and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA, USA), based on sequence information available online [8,9]. To score PCR product sizes for dimorphic microsatellite markers, reactions plus 2 ul loading buffer were electrophoresed through 3.5% NuSieve® agarose (Lonza, Rockland, ME, USA) gels. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under ultraviolet light. In addition to nine standard microsatellite markers [10] on Chr 2 (see Supplementary Figure S1), four DNA markers based on single nucleotide polymorphisms previously-reported to differ between strains AKR and C57BL/6J [8,9] were also scored. These markers (herein designated SNP A–D) are described in detail in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. For sequence analysis, about 1.5 μg of individual PCR amplimers were purified and concentrated into a 30 μl volume using QIAquick® PCR Purification kits (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD, USA). Amplimers were shipped to SeqWright DNA Technology Services (Houston, TX, USA) for primer-extension sequence analysis. Carriers of the recessive Tgm3Btlr allele were identified by primer-extension DNA sequence analysis of a 187 bp PCR product directed by a forward primer (5’ AAAGCCAACAGTGGCAATAATC 3’) that anneals within Exon 3, and a reverse primer (5’CCAACCAGATCTAAGCCCATAC 3’) that anneals within Intron 3–4.

2.3. mRNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from skin samples taken from 1-month-old mutant and wild type mice using the Nucleospin® RNA Midi kit by Macherey-Nagel (Bethlehem, PA, USA). From these total RNA samples poly A+ mRNA was purified using the NucleoTrap® mRNA kit, also by Macherey-Nagel, and cDNA was generated using the SMARTer® RACE 5’/3’ kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). To detect Tgm3- or Actb-specific sequences, primer pairs that flanked exon-junction boundaries were used to direct standard PCR amplifications of these cDNAs, and the resulting products were visualized in 3% NuSieve® agarose gels. For primer-extension sequencing, these products were purified and concentrated (as described above) and shipped to SeqWright DNA Technology Services.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic mapping of we4J

While we has been used extensively as a phenotypic marker for genetic mapping on mouse Chr 2 [5,6] , its location has not been well defined with respect to molecular markers except by Zuberi and coworkers [11,12] who found one crossover that placed we centromeric to Itpa [for inosine triphosphatase (nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphatase)]. To verify and further refine this location, we produced a 1035-member backcross (N2) family by crossing (C57BL/6J x AKR/J-we4J/J)F1 females with AKR/J-we4J/J mutant males. These N2 mice were typed for their hair phenotype, and DNA isolated from each mouse was characterized for nine PCR-scorable microsatellite markers (see Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) that lie throughout the we-critical region identified by Zuberi et al. This analysis located we4J between markers D2Mit304 and D2Mit78, and very near markers D2Mit135 and D2Nds3 (from which we4J was never meiotically separated) (Figure 2A).

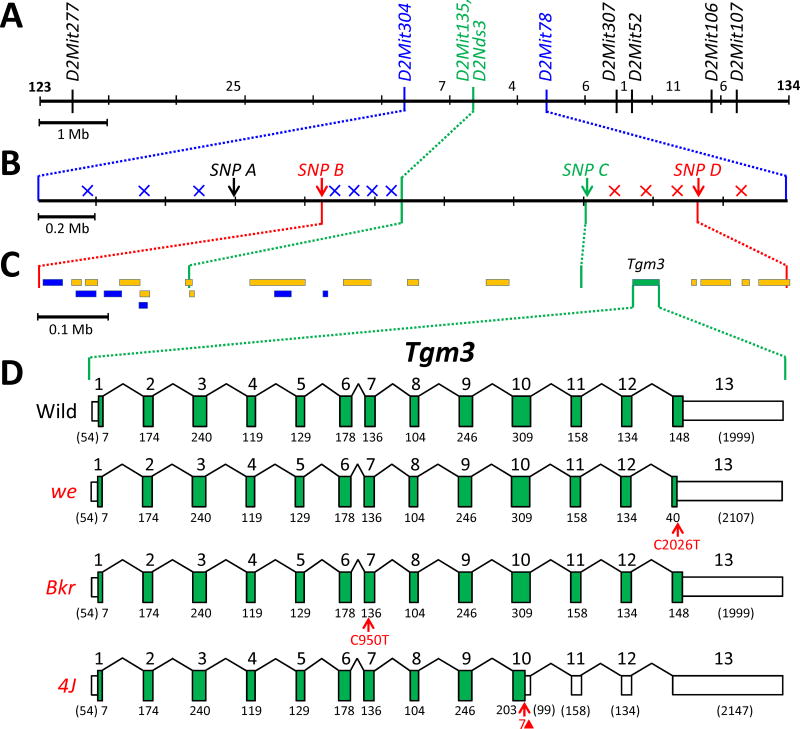

Figure 2.

Physical maps of the “we-critical” region of mouse Chr 2. (A) The relative positions of the nine microsatellite markers typed within the backcross panel are shown, with a 1 Mb scale bar. The number of crossovers found in each marker-defined interval is shown. D2Mit135 and D2Nds3 (shown in green) were never meiotically separated from we4J in this backcross panel. (B) The relative positions of four SNP markers are shown for the 2.1 Mb region that is flanked by D2Mit304 and D2Mit78 (a 0.2 Mb scale bar is shown). Crossovers that fell to the left of (centromeric to) we4J are depicted by blue x’s (drawn arbitrarily within the SNP-defined interval where they were mapped); crossovers that fell to the right of (telomeric to) we4J are shown in red. Therefore, we4J must lie between SNP B and SNP D (shown in red). SNP C (shown in green) was never separated from we4J in this backcross panel. (C) The interval from SNP B to SNP D is expanded (a 0.1 Mb scale bar is shown), and the extent of known genes (in yellow) and processed transcripts (in blue) are depicted by colored rectangles. Of these potential candidates, only Tgm3 (in green) is known to be expressed in skin. (D) The Tgm3 gene is expanded to show the 13 exons it comprises. Tall green boxes represent coding regions and shorter white boxes indicate the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions. The number below each coding segment is its length in base pairs; the base-pair lengths of noncoding segments are in parentheses. The mutant we transcript shows a nonsense mutation in Exon 13 that is predicted to truncate the mutant protein (also see Supplementary Figure S3, Panel A). The mutant weBkr transcript is drawn to show the position of a missense mutation in Exon 7 that is predicted to substitute a highly-conserved, polar serine with a non-polar leucine residue (also see Supplementary Figure S3, Panel B). The we4J transcript is drawn to show the position of the 7-bp deletion we define here (shown as a red triangle) that is predicted to result in an early translational stop (also see Supplementary Figure S3, Panel C)

To more precisely locate we4J, the eleven mice recombinant between D2Mit304 and D2Mit78 were typed for four single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that lie within that interval (and are described in detail in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). This analysis, summarized in Figure 2B, identified four crossovers that positioned we4J telomeric of SNP B and three crossovers that placed we4J centromeric of SNP D (very near SNPC which was never separated from we4J). This small, 1.1-Mb region contains 21 genes or processed transcripts (see Figure 2C), only one of which, Tgm3 (for transglutaminase 3, E polypeptide; also known as epidermal-type transglutaminase), is known to be expressed in skin [13].

3.2. Sequence analysis of Tgm3 in four independent wellhaarig alleles

With one obvious candidate, we next sequenced the exons (both coding and untranslated regions) of the Tgm3 gene in genomic DNA from we, weBkr, we3J and we4J mutants, and from control C57BL/6J and AKR/J mice. DNA defects predicted to cause protein-level alterations were found in three of these four wellhaarig variants: a C to T nonsense mutation in Exon 13 would shorten the we mutant’s Tgm3 product by 36 amino acids, a C to T missense mutation in Exon 7 would replace a polar serine with a nonpolar leucine in the weBkr mutant, and a 7-base-pair deletion in Exon 10 would terminate translation of the we4J mutant’s Tgm3 product at R512 (out of the usual 693 amino acids)(as summarized in Figure 2D). The details of these changes are displayed in Supplementary Figure S3. Notably, DNA isolated from two additional strains said to carry the original we allele (B6C3Fe a/a-we Pax1un at/J and B6CBACa Aw-J/A-we a Mafbkr/J) were shown to encode the same DNA alteration we described for the we allele carried by strain B10.UW-H3b we Pax1un at/SnJ (see Figure 3A). Using additional DNA tests described in Figure 3B and C we also demonstrated that the Tgm3 defects assigned to we4J and weBkr are specific to these variants.

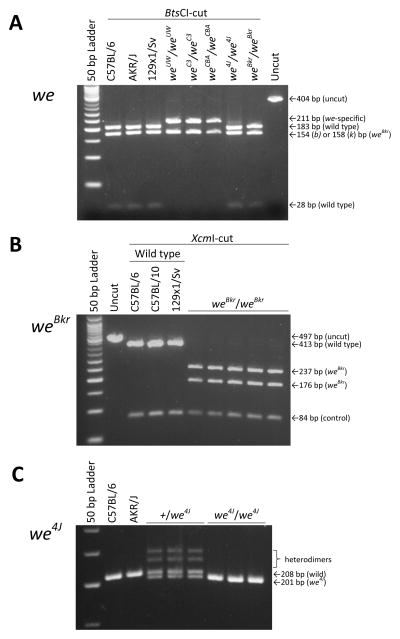

Figure 3.

DNA tests that distinguish three wellhaarig-associated mutations in Tgm3 from the wild-type sequence. (A) 404 or 408 bp amplimers (from C57BL/6-derived Tgm3b templates or from AKR-derived Tgm3k templates, respectively) directed by primers shown in Supplementary Figure S3, Panel A, were cut with restriction endonuclease BtsCI. Amplimers based on wild type templates cut twice, while templates from three inbred mouse strains (B10.UW-H3b we Pax1un at/SnJ, B6C3Fe a/a-we Pax1un at/J and B6CBACa Aw-J/A-we a Mafbkr/J) that are homozygous for the original we mutant allele (distinguished in the figure as weUW, weC3 and weCBA, respectively) cut only once, yielding a 211 bp mutant-specific fragment. Distinct wellhaarig alleles with defects in other regions of the Tgm3 gene (including we4J and weBkr, shown here) exhibit the wild-type cutting pattern. (B) 495 bp wild-type amplimers directed by primers that flank Tgm3, Exon 6 (see Supplementary Figure S3, Panel B) were cut once with endonuclease XcmI, while amplimers based on mutant weBkr templates were cut twice. Digestions were limited to 45 minutes to avoid star activity. (C) Primers located within Tgm3, Exon 10 (see Supplementary Figure S3, Panel C) were used in a standard PCR to amplify a 201 bp product from we4J templates and a 208 bp product from wild-type templates. These products were readily distinguished by electrophoresis through 3.5 % NuSieve agarose gels. Two (fainter) slower-moving bands were generated only from heterozygous templates and presumably result from heterodimer PCR products with retarded migration rates.

3.3. Complementation analysis

Two other laboratories have engineered recessive, loss-of-function alleles of Tgm3 [7,14], and these mutants both show abnormal hair morphology similar to the classic wellhaarig phenotype, further supporting Tgm3 as a candidate for the gene disrupted by the various wellhaarig mutations. We obtained mice homozygous for the recessive Tgm3Btlr allele produced by Bruce Beutler and colleagues (UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA), and called “tortellini” by these investigators [7] (and see Materials and Methods). Table 1 summarizes the results of crosses we conducted between tortellini mutants and mice heterozygous for either we4J or for weBkr. Because the progeny inheriting both a recessive Tgm3Btlr allele and a recessive we4J (or weBkr) allele showed curly hair (while siblings inheriting only the Tgm3Btlr allele did not) we conclude that these mutations “fail to complement”. On this basis we suggest that these two wellhaarig mutations (and by extension, all others) result from defects in Tgm3.

Table 1.

Complementation testing among the recessive weBkr, we4J and Tgm3Btlr mutations confirms allelism.

| Wild Type

|

Mutant

|

χ2

|

P

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female

|

Male

|

Female

|

Male

|

|||

| Cross A. | ||||||

| we4J/we4J X +/weBkr | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2.94 | 0.09 |

| +/weBkr X we4J/we4J | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cross B. | ||||||

| weBkr/weBkr X +/we4J | 6 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1.13 | 0.29 |

| +/we4J X weBkr/weBkr | 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cross C. | ||||||

| Tgm3Btlr/Tgm3Btlr X +/we4J | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.35 |

| +/we4J X Tgm3Btlr/Tgm3Btlr | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cross D. | ||||||

| Tgm3Btlr/Tgm3Btlr X +/weBkr | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1.64 | 0.20 |

| +/weBkr X Tgm3Btlr/Tgm3Btlr | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

Combined counts from reciprocal crosses were tested for goodness-of-fit with the 1 wild type:1 mutant ratio expected for non-complementation using the χ2 test. DNA isolated from the progeny of crosses A and D were typed using the test shown in Figure 3B to confirm that all mutant progeny received the weBkr allele, and that all the wild type progeny did not. DNA isolated from the progeny of crosses B and C were typed using the test shown in Figure 3C to confirm that all mutant progeny received the we4J allele, and that all the wild type progeny did not. One mutant and one wild type pup from each cross (A, B, C and D) are shown in Supplementary Figure S4, Panels A, B, C and D, respectively. Mutant phenotypes resulting from crosses A and B formally confirm that weBkr and we4J are alleles of each other, as well as being alleles of the original we mutation, which was previously demonstrated by Graff et al. for weBkr [2] and by Samples et al. for we4J [4]. Mutant phenotypes resulting from crosses C and D demonstrate that these recessive wellhaarig mutations fail to complement Tgm3Btlr, and may therefore be considered alleles of Tgm3.

3.4. mRNA analysis

The Tgm3Btlr mutation is a G to A transition that destroys the splice donor site at the 5’ end of Intron 3–4, and is predicted by Won, Moresco and Buetler [7] to cause the splicing of Exon 2 with Exon 4, eliminating the 80 amino acids encoded by Exon 3 (see Supplementary Figure S5A, B). To test this hypothesis and to determine if the we4J transcript (with its predicted early termination of translation in Exon 10) might be subject to nonsense-mediated decay [15], Tgm3 sequences were amplified between Exons 2 and 5 from cDNA templates based on poly-A+ mRNA isolated from mutant or wild type skin (see Supplementary Figure S5C). Sequencing of the 586 bp product amplified from wild type, we4J/we4J and weBkr/weBkr skin cDNA verified the normal splicing of Exons 2, 3, 4 and 5. Sequencing of the major 346 bp product amplified from tortellini skin demonstrated that the mutant transcript is almost entirely processed to join Exon 2 with Exon 4, as predicted [7]. Furthermore, while the weBkr and Tgm3Btlr transcripts appear as stable as wild type (as expected, since both of these variants are predicted to be fully translated), the we4J transcript appears consistently underrepresented in both homozygotes and in heterozygotes suggesting that this mutant mRNA is unstable, and is likely subject to nonsense-mediated decay.

4. Discussion

We have taken a positional-candidate approach to assign the classic wellhaarig mutations in mice to defects in the Tgm3 gene. Finding three different, allele-specific Tgm3 defects in we, weBkr and we4J mutants (a nonsense mutation; a missense mutation; and a small, frame-disrupting deletion) strongly supports this assignment. In addition, the failure of an induced, recessive allele of Tgm3 to complement the we4J or weBkr defects in compound heterozygotes confirms allelism. We therefore recommend that these wellhaarig mutations be formally renamed “transglutaminase 3; wellhaarig” (Tgm3we), “transglutaminase 3; wellhaarig 4 Jackson” (Tgm3we-4J) and “transglutaminase 3; wellhaarig Bunker” (Tgm3we-Bkr). No DNA alteration was found in the (mostly) exonic portions of Tgm3 that we sequenced in DNA isolated from a we3J mutant. While we suspect that the we3J allele likely has a regulatory defect in Tgm3 outside of the regions we sequenced, we were not able to investigate possible changes in transcript expression, processing or stability because this variant is no longer extant.

The spontaneous wellhaarig mutations join two engineered Tgm3 alleles [7,14], providing a collection of five phenotypically similar, but mutationally distinct defects. The we mutation is predicted to remove just the final 36 amino acids (658–693) of Tgm3, which compose the final third of the 2nd β-barrel (amino acids 595–693; SSF49309 [16]). Because we do not maintain any live we mutants in our laboratory, it was not determined if the we nonsense defect might destabilize the mRNA (but since this mutant termination codon lies in Exon 13, downstream of the final exon-exon junction in Tgm3, nonsense-mediated decay, at least, does not seem likely). The we4J mutation is predicted to more severely truncate the protein (eliminating residues 513–693), deleting all of the second β-barrel and most of the first (amino acids 481–594; SSF49309 [16]), and also appears to result in an unstable transcript. In the weBkr allele, a missense mutation is predicted to replace Ser299 with a nonpolar leucine residue. While this amino acid lies in the catalytic core of the protein (amino acids 142–461; SSF54001 [16]), this serine is not part of the catalytic triad (Cys273, His331 and Asp354) nor is it near the cleavage site for zymogen activation at Ser465.

In the skin, epidermal transglutaminase is highly expressed in keratinocytes and corneocytes, where it contributes to the formation of the cell envelope by crosslinking substrates such as loricrin and involucrin [17], and in hair follicles, where it catalyzes the crosslinking of trichohyalin and keratin intermediate filaments to harden the inner root sheath [14]. We propose that mutations of Tgm3 may result in the wellhaarig phenotype due to asymmetric crosslinking of proteins in the hair cortex. Indeed, genetic variants of trichohyalin [18] and of hair keratins [19,20] have been associated with changes in hair morphology. Defects in Tgm3 might also, therefore, be expected to influence hair curvature.

In spite of widespread expression of Tgm3 in skin, its ablation in the mouse does not cause any obvious developmental defects, other than altered hair morphology [14] and contact hypersensitivity to fluorescein isothiocyanate [21]. It is therefore probably not surprising that there are, to our knowledge, no examples of human disorders associated with Tgm3 defects. It does seem likely that some recessive forms of hair curling or brittleness could be due to changes in Tgm3, but their pathology may not be severe enough to draw medical attention. Interestingly, however, epidermal transglutaminase has been identified as the primary autoantigen in the gluten-sensitive disease dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), where IgA directed against Tgm3 in the skin form deposits in the papillary dermis [22]. It might be interesting to learn, for example, if any or all of these murine Tgm3 variants might be resistant to gluten-induced antibodies, compared with wild type mice.

Other tissues—including the brain; the tongue, esophagus and stomach; and the testes—also display high levels of Tgm3 expression [23–26] and the role of Tgm3 in the development, maintenance and function of these tissues certainly deserves further investigation. We anticipate that the series of five distinct, naturally-occurring and engineered variants of Tgm3 that we have assembled here will help facilitate such studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Genetic mapping identifies a small number of candidates for the mouse we4J mutation.

Sequence analysis of four wellhaarig alleles reveals three distinct Tgm3 mutations.

Complementation testing shows that two wellhaarig mutations are alleles of Tgm3.

Analysis of skin mRNA indicates that the we4J transcript is unstable.

Analysis of skin mRNA indicates that the Tgm3Btlr transcript is aberrantly spliced.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank undergraduates Alex V. Nesta, Kenneth M. Palanza, Ryan Walters, Anna Battye, Rose Vital, Erin Casey, Avery Ratliff and Shaun Ratliff, and high school interns Julia Rivera, Kavesha Thakkar, David Hyuckin Lim and Ariel Gilgeours for help with marker typing; and Mary Mantzaris for excellent animal care. This work was supported by research grants from the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities System, the Dean of the School of Engineering, Science and Technology, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15-AR059572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A. Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material for this article:

Table S1. Description of SNP markers referred to in the Brennan et al. (2015) text;

Table S2. Location of SNP markers referred to in the Brennan et al. (2015) text;

Figure S1. Dimorphic amplimers for each of nine microsatellite DNA markers used in this study;

Figure S2. Segregation of we4J and nine microsatellite markers on mouse Chr 2 among a large backcross family of mice;

Figure S3. Genomic DNA and predicted amino acid sequences at the site of the we, weBkrand we4J mutations;

Figure S4. Representative mutant and wild type pups resulting from complementation testing among the recessive weBkr, we4J and Tgm3Btlr mutations;

Figure S5. Analysis of Tgm3 mRNA from mutant skin shows that the Tgm3Btlr transcript skips Exon 3, and that the we4J transcript is unstable;

can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ymgme.2015.##.###.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hertwig P. Neue mutationen und koppelungsgruppen bei der hausmaus. Z Indukt Abstamm Vererbungsl. 1942;80:220–246. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graff RJ, Simmons D, Meyer J, Martin-Morgan D, Kurtz M. Abnormal bone production associated with mutant mouse genes pa and we. J Heredity. 1986;77:109–113. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet HO, Davisson MT. Remutations at The Jackson Laboratory. Mouse Genome. 1995;93:1030–1034. (Update to Mouse Genome 1993; 91:862–5) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samples RM, Ward-Bailey P, Gagnon L, Donahue LR. Mouse Genome Database Group: The Mouse Informatics website. The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor ME: 2002. A fourth remutation to wellhaarig (we) at The Jackson Laboratory, MGI Direct Data Submission (J:77566) to Mouse Genome Database (MGD) (Available from: http://www.informatics.jax.org) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundberg JP. The wellhaarig (we, weBkr) mutations, Chromosome 2. In: Sundberg JP, editor. Handbook of Mouse Mutations with Skin and Hair Abnormalities: Animal Models and Biomedical Tools. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. pp. 475–478. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MGI mouse Gene Detail – MGI:98947 – wellhaarig. Retrieved from the Mouse Genome Database (MGD) Mouse Genome Informatics, The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, Maine: Mar, 2015. World Wide Web ( http://www.informatics.jax.org/marker/MGI:98947) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Won S, Moresco EMY, Beutler B. In: Record for tortellini, updated Dec 12, 2013. MUTAGENETIX. Beutler B, et al., editors. Center for the Genetics of Host Defense, UT Southwestern Medical Center; Dallas, TX: Mar, 2015. World Wide Web ( http://mutagenetix.utsouthwestern.edu:80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouse Genome Database (MGD), Mouse Genome Database Group. The Mouse Informatics website. The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor ME: 2015. (Available from: http://www.informatics.jax.org) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ensembl Genome Server (EGS) The European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) and the Welcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) Release 78, 2015. (Available from http://www.ensembl.org)

- 10.Dietrich WF, Miller J, Steen R, Merchant MA, Damron-Boles D, Husain Z, Dredge R, Daly MJ, Ingalls KA, O'Connor TJ. A comprehensive genetic map of the mouse genome. Nature. 1996;380:149–152. doi: 10.1038/380149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuberi AR, Nguyen HQ, Auman HJ, Taylor BA, Roopenian DC. A genetic linkage map of mouse chromosome 2 extending from thrombospondin to paired box gene 1, including the H3 minor histocompatibility complex. Genomics. 1996;33:75–84. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuberi AR, Roopenian DC. High-resolution mapping of a minor histocompatibility antigen gene on mouse chromosome 2. Mamm Genome. 1993;9:516–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00364787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visel A, Thaller C, Eichele G. GenePaint.org: An atlas of gene expression patterns in the mouse embryo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D552–556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John S, Thiebach L, Frie C, Mokkapati S, Bechtel M, Nischt R, Rosser-Davies S, Paulsson M, Smyth N. Epidermal transglutaminase (TGase 3) is required for proper hair development, but not the formation of the epidermal barrier. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e342252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YF, Imam JS, Wilkinson MF. The nonsense-mediated decay RNA surveillance pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:51–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.050106.093909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gough J, Karplus K, Hughey R, Chothia C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: A model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medland SE, Nyholt DR, Painter JN, McEvoy BP, McRae AF, Zhu G, Gordon SD, Ferreira MA, Wright MJ, Henders AK, Campbell MJ, Duffy DL, Hansell NK, Macgregor S, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Montgomery GW, Martin NG. Common variants in the trichohyalin gene are associated with straight hair in Europeans. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGowan KM, Tong X, Colucci-Guyon E, Langa F, Babinet C, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 null mice exhibit age- and strain-dependent alopecia. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1412–1422. doi: 10.1101/gad.979502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean WHI, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, Morley SM, Lane EB, Swensson O, Dopping-Hepenstal PJC, Griffiths WAD, Eady RAJ, Higgins C, Navsaria HA, Leigh IM, Strachan T, Kunkeler L, Munro CS. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nature Genetics. 1995;9:273–278. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bognar P, Nemeth I, Mayer B, Haluszka D, Wikonkal N, Ostorhazi E, John S, Paulsson M, Smyth N, Psztoi M, Buzas EI, Szipocs R, Kolonics A, Temesvari E, Karpati S. Reduced inflammatory threshold indicates skin barrier defect in transglutaminase 3 knockout mice. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2014;134:105–111. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sárdy M, Kárpáti S, Merkl B, Paulsson M, Smyth N. Epidermal transglutaminase (TGase 3) is the autoantigen of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:747–757. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitomi K, Horio Y, Ikura K, Yamanshi K, Maki M. Analysis of epidermal-type transglutaminase (TGase 3) expression in mouse tissues and cell lines. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2001;33:491–498. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitomi K, Presland RB, Nakayama T, Fleckman P, Dale BA, Maki M. Analysis of epidermal-type transglutaminase (transglutaminase 3) in human stratified epithelia and cultured keratinocytes using monoclonal antibodies. J Dermatol Sci. 2003;32:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Zhi HY, Ding F, Luo AP, Liu ZH. Transglutaminase 3 expression in C57BL/6J mouse embryo epidermis and the correlation with its differentiation. Cell Research. 2005;15:105–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckert RL, Kaartinen MT, Nurminskaya M, Belkin AM, Colak G, Johnson GVW, Mehta K. Transglutaminase regulation of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:383–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.