Abstract

Defects in DCLRE1C, PRKDC, LIG4, NHEJ1, and NBS1, involving the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway, result in radiation-sensitive severe combined immunodeficiency (RS-SCID). Results of hematopoietic cell transplantation for RS-SCID suggest that minimizing exposure to alkylating agents and ionizing radiation is important for optimizing survival and minimizing late effects. However, use of pre-conditioning with alkylating agents is associated with a greater likelihood of full T and B cell reconstitution compared to no conditioning or immunosuppression alone. A reduced intensity regimen using fludarabine and low dose cyclophosphamide may be effective for patients with LIG4, NHEJ1 and NBS1 defects although more data are needed to confirm these findings and characterize late effects. For patients with mutations in DCLRE1C (Artemis-deficient SCID), there is no optimal approach that uses standard dose alkylating agents without significant late effects. Until non-chemotherapy agents, e.g., anti-CD45 or anti-CD117 become available, options include minimizing exposure to alkylators, e.g., single agent low dose targeted Busulfan or achieving T cell reconstitution followed several years later with a conditioning regimen to restore B cell immunity. Gene therapy for these disorders will eventually remove the issues of rejection and GvHD. Prospective multi- center studies are needed to evaluate these approaches in this rare but highly vulnerable patient population.

Keywords: SCID, radiation sensitivity, hematopoietic cell transplantation, non-homologous end joining, DNA repair

Argument for and against conditioning

Several DNA repair pathways have evolved to recognize and repair non-programmed DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) resulting from ionizing radiation, alkylating agents and/or replication errors [1]. DSBs activate ATM (Ataxia-Telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3) kinases which phosphorylate as many as 700 proteins that transduce the DNA damage signal, arrest the cell cycle and start DNA repair or, if the damage cannot be repaired, activate apoptosis [2,3]. Unlike most other DNA damage, DNA DSBs directly threaten genomic integrity; thus, these repair processes are essential for preserving genomic structure, and reducing mutagenic risk and oncogenesis. Additionally, abnormal repair of DSBs can result in localized sequence abnormalities and loss of genomic information. More damaging is the joining of the wrong pair of DNA ends resulting in deletions, translocations or inversions.

Two pathways have evolved to repair DNA DSBs: homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [1]. HR functions primarily in dividing cells and S phase, and requires a homologous template to maintain replication accuracy. NHEJ can operate in dividing or non-dividing cells regardless of the cell cycle phase, but is particularly employed during phases of the cell cycle when a homologous template is not present. Unlike HR, NHEJ is an error-prone process with some loss of DNA information at the site of the DSB.

NHEJ also operates to repair damaged DNA following programmed DNA DSBs, critical for development of B and T lymphocyte receptor diversity associated with V(D)J recombination [4]. During T and B lymphocyte development DSBs are introduced during lymphocyte antigen receptor development, immunoglobulin class switch recombination, and somatic hypermutation. V(D)J recombination is initiated by enzymes coded by the recombination activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG1/2) which form a complex that randomly introduces nicks in DNA by recognizing highly conserved sequences of DNA, recombination signal sequences (RSSs), that flank all V, D, and J coding regions (Figure 1). Defects in RAG1 or RAG2 result in failure to initiate the V(D)J recombination process with subsequent failure to generate T and B lymphocytes and cause one variant of the most severe primary immunodeficiencies: T negative B negative NK positive severe combined immunodeficiency (T−B−NK+ SCID). There are 5 other genes involved in V(D)J recombination and which are in the NHEJ pathway, mutations in which cause T−B−NK+ SCID: DCLRE1C which codes for an endonuclease (Artemis), PRKDC which codes for a phosphokinase (DNA-PKcs), LIG4 which codes for DNA ligase 4, NHEJ1 which codes for Cernunnos, and NBS1 which codes for Nibrin and is part of the MRE11 complex which has a role in the end processing step in NHEJ along with Artemis and several other proteins [4–8]. The major distinction between RAG1/2-defective SCID and SCID associated with defects in the NHEJ pathway is that the NHEJ enzymes are ubiquitously found in all nucleated cells, such that fibroblasts and induced pluripotent stem cells from affected patients display general susceptibility to alkylating agents and ionizing radiation commonly used in conditioning regimens prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while defects in RAG1/2 result in T−B−NK+ SCID without increased susceptibility to alkylating agents and ionizing radiation [9–11].

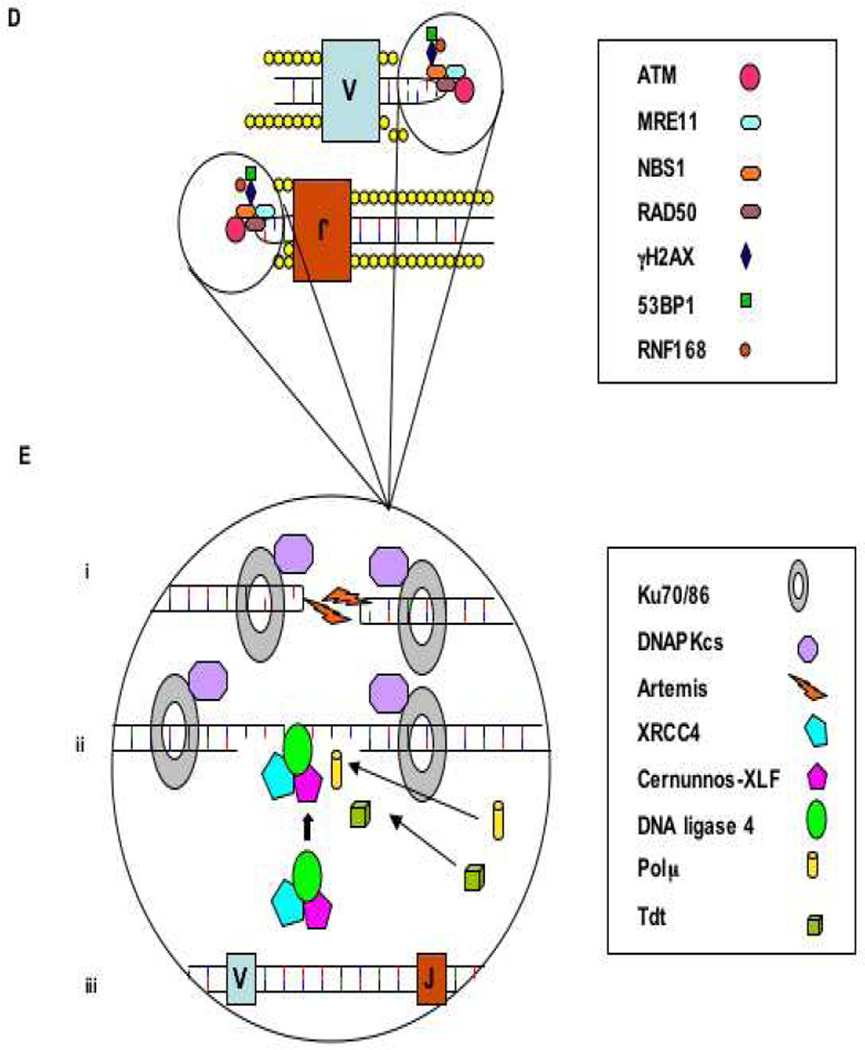

Figure 1.

A.

A. DNA is uncoiled at transcription “factories” within the cell, where the associated recombination and repair proteins co-localize.

B. The lymphoid specific recombinase activating gene 1 and 2 (RAG1/2) proteins recognize and bind the recombination signal sequences (RSS) that flank the V(D)J gene segments, and introduce site-specific DNA-DSBs.

C. The phosphorylated blunt signal ends and the covalently sealed hairpin intermediate of the coding end are held together by the RAG complex.

B.

D. The MRN complex binds the broken DNA ends and activates ATM which initiates cell cycle arrest and attraction of the repair proteins. H2AX, 53BP1 and RNF168, and with other proteins stabilize the damaged chromatin.

Ei. Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds the coding ends and recruits DNA-PKcs and Artemis, which is required to open the hairpin intermediates. The covalently sealed hairpin intermediate is randomly nicked by the DNA-Pkcs/Artemis complex, which generates a single stranded break with 3’ or 5’ overhangs. Eii. XRCC4, DNA ligase 4 and cernunnos-XLF (C-XLF) co-associate and are recruited to the ends. The signal ends are directly ligated by the XRCC4/DNALIG4/ C-XLF complex. The opened hairpin intermediate is modified by polymerases, exonucleases and the lymphoid-specific terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), before

Eiii. being repaired and ligated by the XRCC4/DNA-LIG4/C-XLF complex

Patients with Ataxia-Telangiectasia develop progressive neurodegeneration, combined T and B cell immunodeficiency, and have an elevated incidence of malignancy and increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation [12]. While some improvement in the phenotype has been reported in Atm-deficient mice following HCT [3] there is very limited experience with HCT in affected children although there is at least one case report of a child with AT and ALL surviving in remission for at least 3.5 years post matched sibling HCT [13].

Controversy remains as to whether or not chemotherapy conditioning is required for normal immunoreconstitution following HCT for SCID [14]. When an HLA matched sibling donor is used, the likelihood of T and B cell reconstitution even without conditioning is high regardless of the type of SCID [15–17] although depending on the study and SCID genotype this can vary from 47–81% of patients [16,18]. When an HLA matched sibling is not available, alternative donors such as haplocompatible relatives or unrelated volunteers or cord blood donors are used. When closely matched unrelated donors are used without conditioning, depending on the SCID genotype/phenotype, T cell rather than B cell reconstitution is more likely although GVHD is a significant risk factor with unrelated donors especially when serotherapy is not used [18]. T and B cell reconstitution can also vary with genotype. For example, patients with γc- or JAK3-SCID easily engraft with related haplocompatible T cell depleted (TCD) grafts fully reconstituting T but often without B cell immunity [17,19] while 60–70% of patients with RAG-deficient or RS-SCID reject these grafts when no conditioning is used and maternal chimerism is not present at the time of HCT [19,20].

For the group of patients who have maternal cells present at the time of HCT, it appears that use of the mother as the donor if an HLA matched sibling or unrelated donor is not available can successfully reconstitute at least T cell immunity without conditioning although the data are limited [19]. In one center’s unpublished experience with T−B−NK+ Artemis- or RAG-deficient SCID 1/5 unconditioned recipients without maternal chimerism engrafted with a maternal donor while 8/8 patients with maternal cells present engrafted with the mother as the donor resulting in T but not B cell reconstitution although the degree of T cell reconstitution varied and often was incomplete (MJ Cowan, personal communication). Interestingly, the ART-SCID patient who engrafted without maternal chimerism present was treated with Alemtuzumab as the only conditioning agent [21]. The mechanism for the engraftment of maternal cells in the presence of maternal chimerism pre-HCT has not been evaluated although a possible explanation may be that the KIR receptor expression between the mother (donor) and child (recipient) favors engraftment.

When reduced-intensity (RIC) or myeloablative (MAC) conditioning is used the likelihood of T and B cell reconstitution is increased significantly regardless of the donor as shown in a study of 240 patients with SCID transplanted in North America from 2000 through 2009 [16]. In this study there were 136 infants surviving 2–5 years post HCT of whom 54% had ceased gammaglobulin therapy. For those who were treated with RIC or MAC there was an 84% (CI 69–93%) chance of ceasing gammaglobulin supplementation vs a 41% (CI 31–52%) chance for patients who received no conditioning or immunosuppression alone (p<0.001). A similar observation was made regarding reconstitution of T cell immunity as defined by a CD3 count >1000/mm3, i.e., 89% (CI 75–97) for recipients of RIC or MAC vs 62% (CI 51–73) for recipients of none or immunosuppression alone (p=0.007). It should be noted, however, that even with conditioning a not insignificant percent of SCID patients will still fail to fully reconstitute T and/or B cell immunity.

Exposure of infants to RIC or MAC is associated with some risk not only for potential late effects but also with repect to survival, in particular, those SCID patients who are infected at the time of HCT and for those receiving a mismatched related donor (MMRD) with conditiniong regardless of infection at the time of HCT. In the North American study age and infection at time of transplant were critical determinants of 5 year survival [16]. For those transplanted at <3.5 months of age there was no significant difference in 5 year survival regardless of donor type, cell source or conditioning versus no conditioning regimen. However, patients who were infected at the time of HCT the outcome was significantly better for recipients of haplocompatible grafts who did not receive conditioning for their transplant compared to those who did. Regardless of the SCID genotype, age or infection status, recipients of HLA matched sibling bone marrow grafts had the best outcome with the majority receiving no conditioning prior to HCT. Late effects of conditioning were not evaluated in this study.

The presence of a defect in NHEJ with increased sensitivity to alkylators and ionizing radiation adds another dimension to the debate regarding conditioning prior to HCT. Not only are affected children generally young (<1 year old) at the time of transplant, but some of these NHEJ defects are associated with other abnormalities including microcephaly, developmental delay, and poor growth. Exposure to alkylators or even low dose total body irradiation (TBI) may worsen the CNS damage inherent from their underlying defect, and further retard growth potential. With newborn screening for SCID becoming commonplace in North America [22] and soon to be introduced in Europe and elsewhere, the issue of damage from exposure to chemotherapy in these very young babies becomes potentially even more critical. However, to date there have been no detailed studies to address the effect on longterm morbidity and mortality of a single course of high dose alkylating chemotherapy in infants with SCID in contrast to patients with malignancy exposed to repeated courses.

Issues to consider when thinking about treatment for these patients include survival from the initial procedure, the quality of engraftment and long-term durability of T and B lymphocyte function, as well as the potential short- and long-term effects of chemotherapy. Broadly, 2 groups of patients could be considered, those that have a defect due to enzymes involved in the ligation pathway of a DNA DSB repair defect, i.e., patients with Ligase IV, Cernunnos-XLF or to a lesser extent Nibrin deficiencies, and patients who have Artemis or DNA-PKcs deficiencies, which are involved in stabilizing the initial break.

Results of HCT for radiation sensitive SCID

There is scarce information available for patients with Ligase IV, Cernunnos- XLF, or Nibrin deficiencies who have undergone HCT and therefore care must be taken in the interpretation of the available data. Given that the DNA DSB repair pathway interacts with those pathways involved in defects leading to Fanconi anemia, the relative risk of using chemotherapy may be similar, although a direct comparison of the ex vivo sensitivity of cells from Artemis-deficient patients to DNA damaging agent, mitomycin C, demonstrated decreased sensitivity compared to cells from patients with Fanconi anemia and Xeroderma Pigmentosum [10]. As these patients have NK cells present and often a low number rather than complete absence of T lymphocytes, some conditioning is likely to be needed. Because of the inherent susceptibility of all cells to damage by alkylators, poor tolerance to systemic toxicity possibly including the tissue response to GvHD may be anticipated.

Very few reports of patients with these disorders following HCT have been published and there are only a limited number of unpublished patient experiences. Furthermore, patients have had a variety of underlying reasons for transplantation (marrow failure, infection, immunodeficiency), undergone different RIC or MAC conditioning regimens, and have had different donors resulting in variable outcomes. However, by piecing together published and unpublished data, some general conclusions can be drawn (Table 1). For DNA Ligase IV deficiency, information is available on 12 patients (10 published [7,23–29]) who have undergone transplantation: four patients died (two from multi-organ failure during the conditioning period, one from Epstein Barr virus-driven post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and one from hepatic veno-occlusive disease), all of whom received Busulfan and cyclophosphamide; six patients have survived, three received RIC, two received Busulfan and cyclophosphamide, and one in whom the conditioning regimen is unknown. In two patients neither the conditioning regimen nor the outcome is known. For patients with Cernunnos- XLF, there have been five published transplants [30–32], and a further case known to the authors. One patient, who had received RIC, died from acute graft versus host disease and disseminated cytomegalovirus. Three patients survived, one of whom received RIC, and two who received a non-conditioned infusion. For two patients there are no details available on conditioning regimen or outcome.

Table 1.

Outcomes of transplants for defects in NHEJ proteins.

| Defect | Number Published (unpublished) |

Conditioning Survived (unpublished) |

Conditioning Died (unpublished) |

Outcome Unknown |

References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIC | MAC | None | UK | RIC | MAC | Unknown | ||||

| DNA Ligase IV | 10 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 7,23–29 | |||

| Cernunnos-XLF | 5 (1) | 1 | 2 | (1) | 2 | 30–32 | ||||

| Nibrin | 8 (1) | 7 (1) | 1 | 33–35 | ||||||

Abreviations: RIC = reduced intensity conditioning; MAC = myeloablative conditioning; UK = unknown.

A total of eight patients with Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome who underwent HCT have been reported, and a further case is known to the authors [33–35]. Eight have survived all of whom received RIC. The patient who received Busulfan and cyclophosphamide died pre-engraftment from bacterial sepsis [34].

In summary, 12 of 13 (92%) patients with Ligase IV, Cernunnos- XLF, or Nibrin deficiencies who received RIC are alive, whereas 2 of 5 (40%) who had a non RIC regimen survived while only one of six who received MAC survived. Two patients who received an unconditioned HCT survived. In five other patients there is no specific detailed information, although at least one was alive at the time of publication. No long-term follow up regarding quality of engraftment, immune function, quality of life and late effects are available.

While only one patient with DNA-PK deficiency has been reported to have undergone unconditioned HCT, much more information is available for patients with ART-SCID. In O’Marcaigh et al [36], 14 patients with ART-SCID were transplanted (while 16 were reported in the paper, two siblings were subsequently found to have RAG rather than Artemis deficiency); five of the 14 received no conditioning or ATG alone, five received cyclophosphamide and ATG, and four received cyclophosphamide and Busulfan or TBI with ATG. Seven had HLA matched sibling donors and seven underwent T-depleted haplocompatible parental marrow transplants. No patient developed GvHD greater than grade 2. Nine of 14 are alive. All five patients who died received cyclophosphamide with ATG or cyclophosphamideand Busulfan or TBI and ATG. The one recipient of an HLA matched sibling graft conditioned with cyclophosphamide developed multiple episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage at 5 years post HCT that lead to chronic lung disease and death at 19 years of age. Three patients required boost infusions but the large majority of patients developed T lymphocyte function with CD4+ and CD8+ CD45RA+ cells (M Cowan, personal communication). Only three of 14 developed B lymphocytes, all of whom had been conditioned. There were significant adverse events in patients who received conditioning with alkylators including growth retardation and dental abnormalities. Interestingly, one of the three who is independent of gammaglobulin supplementation received an HLA matched sibling graft with cyclophosphamide pre-conditioning and has also delivered twins (M Cowan, personal communication).

It should be noted that the patients in this report [36] were Athabascan-speaking Native Americans and presented early (≤3 months of age). While these affected Native Americans have an immunophenotype comparable to other patients with ART-SCID, the possibility that they are not representative of other Artemis-deficient patients has been addressed. In the large study of ART- vs RAG-SCID by Schuetz et al [20] it was found that compared to other Artemis-deficient patients, the Athabascan-speaking Native Americans had more frequent orogenital ulcers at presentation than non-Athabascan ART-SCID patients (53% vs 14%, respectively, p<0.05) and less frequent viral infections prior to HCT (p<0.01) while other features were comparable including abnormal dental development when exposed to alkylators (100% in both subcohorts). Also, a single-center study with a median of 14 years follow-up found a striking difference in event-free survival between patients with non-Athabascan ART-SCID and SCID due to other defects including RAG mutations [15].

Mazzolari et al. [37] described two patients with ART-SCID who were 11 and 13 years post transplant. Both received cyclophosphamide-based conditioning and had a matched sibling or unrelated donor. One patient developed grade 3 GvHD, which resolved, but both patients had normal T lymphocyte numbers, evidence of thymopoiesis, B lymphocyte engraftment and off gammaglobulin replacement. Both patients have full or mixed tri-lineage donor chimerism. One patient has ataxia, hypotonia, and epilepsy and requires continuous treatment with antiepileptic drugs as the consequence of encephalitis that occurred early after HSCT, while no abnormalities were reported for the other patient.

Cavazzano-Calvo et al. [38] evaluated two Artemis-deficient patients who received maternal T lymphocyte depleted marrow with no conditioning. At 13 years follow up, they had low TREC numbers with poor thymopoiesis, recipient myeloid cells and remained on gammaglobulin replacement.

In the largest retrospective three center study (University of California San Francisco Benioff Children's Hospital, Hopital Necker-Enfants Malades, Paris, France, and the Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, University Medical Center Ulm, Germany) of early and late outcomes following HCT of patients with T−B−NK+ SCID with or without increased sensitivity to alkylating agents and ionizing radiation, Schuetz et al [20] evaluated 69 patients with ART-SCID versus 76 patients with RAG-SCID, a number of whom had previously been reported [15,20]. The two groups were comparable with respect to donor type and exposure to alkylating agent therapy and a variety of other transplant characteristics. Overall survival was similar in each group (Artemis 67%, RAG 63%) and there was no difference in survival depending on the donor type between the two groups. Early toxicity was noted equally in both groups particularly mucositis and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Acute GvHD was noted in both groups as well as systemic infection. Death was experienced in both RAG-SCID and ART-SCID patients and factors associated with mortality included viral infection prior to transplantation, an age of greater than 3 months prior to diagnosis, presence of chronic GvHD, and necessity of re-transplantation. However, factors which were not associated with mortality were Omenn Syndrome, use of a haploidentical donor or the type of conditioning regimen, including alkylating agents.

Importantly, a sub-cohort of 92 patients with either ART- or RAG-SCID who were at least two years post-transplant was also studied for outcome, complications and quality of immune reconstitution with a follow up of 2 to 28 years (median 8.5 years). There were 47 patients with ART-SCID and 45 with RAG-SCID. There was no difference between the groups in the numbers of patients that received alkylating therapy, nor in immunologic reconstitution with similar numbers of patients having low numbers of CD4 T lymphocytes or naive T lymphocytes or remaining on gammaglobulin. Significantly more patients with RAG-SCID had full donor myeloid chimerism although more of those patients received MAC. There was significantly improved immunoreconstitution at two years post-transplant in recipients of myeloablation both with respect to T lymphocyte numbers and freedom from immunoglobulin replacement (p<0.001). However, late complications were significantly more common (P<0.001) in patients with ART- SCID and included infections, immunodysregulation, noninfectious/nonautoimmune endocrinologic dysfunction, growth problems and permanent teeth abnormalities. Twenty-one percent of the 47 ART-SCID patients versus 0% of the RAG-SCID patients had dental abnormalities including abnormal roots and failure to develop permanent teeth. Factors predictive of poor growth in the Artemis-deficient patients included MAC and the use of alkylating agents. Among patients >5 years of age at the time of the study who had received alkylators, 86% of Artemis and only 12% of RAG-deficient patients had growth deficiency. Boys with ART-SCID following alkylator therapy had the greatest loss in height (p<0.0001) versus males not receiving alkylators.

In summary, MAC prior to HCT is associated with better engraftment, long term thymopoiesis and B lymphocyte function in patients with radiosensitive SCID associated with Artemis-deficiency and with no significant increase in immediate complications or mortality. Unfortunately, there is a significant increase in the risk of long-term morbidity following alkylator chemotherapy in this patient population, particularly with respect to growth, endocrine, dental and nutritional problems. This is in contrast to patients with other radiosensitive disorders, including DNA Ligase 4, Cernunnos and Nibrin deficiency (Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome) in which myeloablative therapy does not appear to be essential and appears to be associated with increased early mortality. The data are too limited to comment on patients with DNA-PKcs abnormalities. While they may behave like those patients with ART-SCID there is one report of DNA-PKcs-deficiency with severe developmental delay which may indicate broader adverse effects beyond the immune system [39]. Further experience with HCT for these patients will help to clarify this issue.

How to resolve the dilemma?

The dilemma for transplant physicians and immunologists treating these patients is that the use of myeloablative conditioning prior to HCT for patients with SCID results in increased donor chimerism and a greater likelihood of normal T and B lymphocyte reconstitution. However, in those patients with active infection at the time of HCT the 5 year outcome is significantly better in patients who do not receive any conditioning [16]. With the increase in universal newborn screening for SCID, this issue may become less relevant as patients will be less likely to be infected. However, the long-term outcome and late effects associated with exposure of young infants to high dose alkylators has not been studied in any detail to date in a heterogeneous cohort of patients with SCID, and is of great concern and remains to be determined.

For the radiation-sensitive SCID patients the dilemma is even more profound. While for some genotypes, i.e., DCLRE1C, early side effects and survival do not appear to be significantly affected by exposure to alkylator therapy, other genotypes (LIG4, NHEJ1, and NBS1) appear to be associated with decreased survival following MAC, and the late effects of exposure to RIC and MAC remain to be determined for all of these disease types.

What to do?

Currently, what are the least toxic regimens that avoid or minimize exposure to alkylating agents and TBI that induce DNA DSBs which these patients have significant difficulty in repairing? Firstly, radiotherapy is not required to successfully engraft these patients, and should be avoided. Secondly, for those with DNA Ligase 4, Cernunnos or Nibrin abnormalities RIC seems to be well-tolerated, with good engraftment and immediate survival. In fact, a regimen modified from that used for Fanconi’s anemia, with the use of serotherapy, fludarabine and very low dose cyclophosphamide (total of 20mg/kg) (http://esid.org/layout/set/print/content/download/365/1635/file/BMT_Guidelines_2011.pdf) as published by the ESID/EBMT Inborn Errors Working Party, has been well tolerated with 10 of 12 (83%) patients surviving (A Gennery, personal communication). However, the long-term effects of such a regimen are unknown and careful long-term follow-up of these patients will be required. Because these patients often present with marrow failure syndromes (with or without severe immunodeficiency) and therefore appear to have abnormal hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) it is possible that very low doses of cyclophosphamide may be sufficient to obtain robust multilineage engraftment with T and B lymphocyte reconstitution without the need for Busulfan to open marrow niches. Also, it should be emphasized that patients with marrow failure syndromes who are being considered for HCT should be evaluated for possible radiation sensitivity and associated defects even without a history of infections.

Thirdly, for patients with Artemis-deficiency, there is no obvious HSC defect (although unpublished data suggest one, MJ Cowan, personal communication) and thus no reason to believe that the modified ESID/EBMT/IEWP conditioning regimen for Ligase 4, Cernunnos, or Nibrin patients is sufficient to open marrow niches in ART-SCID. In fact, the experience with ART-SCID supports the belief that high dose cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg) alone does not reliably restore B lymphocyte immunity [20,36,40]. Thus, some form of therapy that targets marrow niches is required. Unfortunately, while these patients seem to tolerate marrow ablative alkylating agents in the conditioning regimen in the short-term comparable to RAG-SCID patients [20], there are significant long-term side effects from these agents. While the modified Fanconi anemia approach is unlikely to be effective, studies evaluating low-dose Busulfan with careful targeting of drug exposure using newer pharmacokinetic models are needed [41]. Other approaches to opening marrow niches such as targeting CD117, the cKit receptor on HSC [42] warrants further exploration in these patients if a clinical agent becomes available. Other conditioning regimens using antibody-based (e.g., anti-CD45) minimal intensity conditioning to open marrow niches have been used successfully in patients with primary immune deficiencies but none with radiosensitive SCID and need to be evaluated [43].

There is virtually no reported experience with low-dose cyclophosphamide alone (<200mg/kg) to prevent rejection. In a single Artemis-deficient patient who received a T-cell depleted unrelated donor transplant, 200 mg/kg cyclophosphamide and low dose busulfan conditioning were inadequate to prevent rejection, even after a boost attempt [40] so that this remains a very difficult problem for this patient population. The reported experience with fludarabine is very limited in the setting of haplocompatible donors where NK-mediated graft rejection is a problem. The efficacy of fludarabine, however, in suppressing NK function in vitro appears to be ineffective [44]. In an attempt to suppress NK cells, a limited number of Artemis-deficient patients without maternal chimerism received a TCD haplocompatible parental graft following pre-treatment with Alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody known to target all lymphocytes [21]. Unfortunately, benefit from this therapy was not uniformly seen and T lymphocyte reconstitution was delayed in the engrafted patients.

Finally, there is the option of using ablative doses of Busulfan (or Treosulfan which may be less toxic than Busulfan [45]) in patients with ART-SCID in spite of the increased risks [15,20]. If a higher intensity conditioning regimen using alkylator therapy is considered, it is essential that the transplant physician inform the parents of the potential serious late effects that might develop.

Until effective non-alkylator therapy for opening marrow niches and preventing NK cell-mediated rejection is available for patients with ART-SCID we need prospective multicenter studies that evaluate rational approaches to treating this vulnerable patient population with the least toxic agents available and, if possible, limit the exposure to one alkylating agent. A possible approach, although it needs to be tested, especially for newborns and those with infections at the time of HCT would be a two-step strategy to immune reconstitution: first, reconstitute sufficient T lymphocyte immunity to ensure long term survival using minimal to no conditioning [19,46]. For patients with HLA-matched siblings, or maternal chimerism, engraftment with achievement of T lymphocyte reconstitution should be possible without exposing these infants to alkylator therapy at a time when they are most susceptible. If a patient has a matched unrelated donor it may or may not be possible to achieve T cell engraftment depending on the genotype and the risk of GVHD is not insignificant if serotherapy is omitted pre-transplant [18]. For those patients with no sibling donor or maternal chimerism there is still a chance that some (40%) will engraft without any conditioning using a T lymphocyte depleted haplocompatible donor [19]. However, with alternative donors and no maternal chimerism a transplant with cyclophosphamide may be necessary although preferably at a lower dose although the risk of rejection may be higher [40]. Some of these patients especially those receiving HLA matched grafts may recover B lymphocytes following the initial unconditioned HCT and may not need additional therapy. However, for those who fail to make antibody and/or have poor T lymphocyte immunity after 2–3 years of age, a boost transplant with some form of therapy to open marrow niches, e.g., targeted Busulfan or Treosulfan could then be performed. This would certainly allow time for permanent tooth buds to develop and possibly increase chances for more normal dental development and more normal stature. There is at least one published report of this approach being successful in a patient with ART-SCID [47]. However, this two-stage approach also has inherent risk, including the potential higher risk of infections and greater risk of graft versus host disease associated with older age as well as diminished thymopoiesis with increasing age, although it appears that haplocompatible related transplants can successfully reconstitute T cell immunity and maintain thymopoiesis without conditioning if done sufficiently early in life [48]. Ultimately, the transplantation of gene-corrected autologous CD34+ cells will at least eliminate the need for anti-rejection chemotherapy and the risk of GvHD although the need for opening the marrow niche to achieve B cell reconstitution remains. Currently many of the gene therapy protocols in patients do require chemotherapy, albeit at low doses. Moreover, low dose busulfan or irradiation were required for efficient lentivirus mediated gene therapy in leaky Artemis-deficient mice [49,50].

While our knowledge of these complex radiation-sensitive disorders is incomplete, accumulating data suggest that they do not tolerate the same conditioning regimens used for patients with other types of SCID. We need to develop alternative approaches that spare these children the deleterious effects of alkylating therapy while still achieving full T and B cell reconstitution. By doing so, we will develop approaches that may in fact, benefit all patients undergoing these kinds of procedures.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Office of Rare Disease Research (ORDR) and the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), U54-AI 082973 and R13 AI 094943. The views expressed in written materials or publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

- SCID

Severe combined immunodeficiency

- NHEJ

Non-homologous end joining

- HR

homologous recombination

- RSS

recombination signal sequences

- NK

natural killer

- HCT

hematopoietic cell transplantation

- GvHD

graft versus host disease

- DSB

double strand break

- RIC

reduced intensity conditioning

- MAC

myeloablative conditioning

- ATG

anti-thymocyte globulin

- TBI

total body irradiation

- NBS

Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome

- ART-SCID

Artemis-deficient SCID

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- ATM

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase

- ATR

ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This manuscript is the result of a debate during the 3rd Annual Primary Immune Deficiency Treatment Consortium Scientific Workshop held in Houston, TX, May 2–4, 2013.

References

- 1.Iyama T, Wilson DM., 3rd DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:620–636. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czornak K, Chughtai S, Chrzanowska KH. Mystery of DNA repair: the role of the MRN complex and ATM kinase in DNA damage repair. J Appl Genet. 2008;49:383–396. doi: 10.1007/BF03195638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietzner J, Baer PC, Duecker RP, Merscher MB, Satzger-Prodinger C, Bechmann I, et al. Bone marrow transplantation improves the outcome of Atm-deficient mice through the migration of ATM-competent cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:493–507. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deriano L, Roth DB. Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:433–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moshous D, Callebaut I, de Chasseval R, Corneo B, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, et al. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell. 2001;105:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Burg M, Ijspeert H, Verkaik NS, Turul T, Wiegant WW, Morotomi-Yano K, et al. A DNA-PKcs mutation in a radiosensitive T-B- SCID patient inhibits Artemis activation and nonhomologous end-joining. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:91–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI37141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enders A, Fisch P, Schwarz K, Duffner U, Pannicke U, Nikolopoulos E, et al. A severe form of human combined immunodeficiency due to mutations in DNA ligase IV. J Immunol. 2006;176:5060–5068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, Barraud A, Fondanèche MC, Sanal O, et al. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felgentreff K, Du L, Weinacht KG, Dobbs K, Bartish M, Giliani S, Schlaeger T, et al. Differential role of nonhomologous end joining factors in the generation, DNA damage response, and myeloid differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323649111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musio A, Marrella V, Sobacchi C, Rucci F, Fariselli L, et al. Damaging-agent sensitivity of Artemis-deficient cell lines. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1250–1256. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans PM, Woodbine L, Riballo E, Gennery AR, Hubank M, Jeggo PA. Radiation-induced delayed cell death in a hypomorphic Artemis cell line. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1303–1311. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavin MF. Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;10:759–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ussowicz M, Musiał J, Duszeńko E, Haus O, Kałwak K. Long-term survival after allogeneic-matched sibling PBSC transplantation with conditioning consisting of low-dose busilvex and fludarabine in a 3-year-old boy with ataxia-telangiectasia syndrome and ALL. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:740–741. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haddad E, Leroy S, Buckley RH. B-cell reconstitution for SCID: should a conditioning regimen be used in SCID treatment? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neven B, Leroy S, Decaluwe H, Le Deist F, Picard C, Moshous D, et al. Long-term outcome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation of a single-center cohort of 90 patients with severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 2009;113:4114–4124. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai SY, Logan BR, Griffith LM, Buckley RH, Parrott RE, Dvorak CC, et al. Transplantation outcomes for severe combined immunodeficiency, 2000–2009. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:434–446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckley RH, Win CM, Moser BK, Parrott RE, Sajaroff E, Sarzotti-Kelsoe M. Post-transplantation B cell function in different molecular types of SCID. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:96–110. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvorak CC, Hassan A, Slatter MA, Hönig M, Lankester AC, Buckley RH, et al. Comparison of outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without chemotherapy conditioning by using matched sibling and unrelated donors for treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.021. pii: S0091-6749(14)00886-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dvorak CC, Hung GY, Horn B, Dunn E, Oon CY, Cowan MJ. Megadose CD34(+) cell grafts improve recovery of T cell engraftment but not B cell immunity in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency disease undergoing haplocompatible nonmyeloablative transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuetz C, Neven B, Dvorak CC, Leroy S, Ege MJ, Pannicke U, et al. SCID patients with ARTEMIS vs RAG deficiencies following HCT: increased risk of late toxicity in ARTEMIS-deficient SCID. Blood. 2014;123:281–289. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dvorak CC, Horn BN, Puck JM, Adams S, Veys P, Czechowicz A, et al. A trial of Alemtuzumab adjunctive therapy in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with minimal conditioning for severe combined immunodeficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:609–616. doi: 10.1111/petr.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, Brower A, Andruszewski K, Abbott JK, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States. JAMA. 2014;312:729–738. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunebaum E, Bates A, Roifman CM. Omenn syndrome is associated with mutations in DNA ligase IV. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1219–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Driscoll M, Cerosaletti KM, Girard PM, Dai Y, Stumm M, Kysela B, et al. DNA ligase IV mutations identified in patients exhibiting developmental delay and immunodeficiency. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruhn B, Seidel J, Zintl F, Varon R, Tönnies H, Neitzel H, et al. Successful bone marrow transplantation in a patient with DNA ligase IV deficiency and bone marrow failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buck D, Moshous D, de Chasseval R, Ma Y, le Deist F, Cavazzana-Calvo M, et al. Severe combined immunodeficiency and microcephaly in siblings with hypomorphic mutations in DNA ligase IV. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:224–235. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Burg M, van Veelen LR, Verkaik NS, Wiegant WW, Hartwig NG, Barendregt BH, et al. A new type of radiosensitive T-B-NK+ severe combined immunodeficiency caused by a LIG4 mutation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:137–145. doi: 10.1172/JCI26121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straathof KC, Rao K, Eyrich M, Hale G, Bird P, Berrie E, et al. Haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation with antibody-based minimal-intensity conditioning: a phase 1/2 study. Lancet. 2009;374:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unal S, Cerosaletti K, Uckan-Cetinkaya D, Cetin M, Gumruk F. A novel mutation in a family with DNA ligase IV deficiency syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:482–484. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faraci M, Lanino E, Micalizzi C, Morreale G, Di Martino D, Banov L, et al. Unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Cernunnos-XLF deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:785–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai Y, Kysela B, Hanakahi LA, Manolis K, Riballo E, Stumm M, et al. Nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination require an additional factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2462–2467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437964100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Çağdaş D, Özgür TT, Asal GT, Revy P, De Villartay JP, van der Burg M, et al. Two SCID cases with Cernunnos-XLF deficiency successfully treated by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:E167–E171. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivović V, Ajzenberg D, Djurković-Djaković O. Atypical strain of Toxoplasma gondii causing fatal reactivation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantion in a patient with an underlying immunological deficiency. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2686–2690. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01077-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert MH, Gennery AR, Greil J, Cale CM, Kalwak K, Kondratenko I, et al. Successful SCT for Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:622–626. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woźniak M, Krzywoń M, Hołda MK, Goździk J. Reduced-intensity conditioning umbilical cord blood transplantation in Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Pediatr Transplant. 2015 Mar;19(2):E51–E55. doi: 10.1111/petr.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Marcaigh AS, DeSantes K, Hu D, Pabst H, Horn B, Li L, Cowan MJ. Bone marrow transplantation for T-B- severe combined immunodeficiency disease in Athabascan-speaking native Americans. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:703–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzolari E, Forino C, Guerci S, Imberti L, Lanfranchi A, Porta F, et al. Long-term immune reconstitution and clinical outcome after stem cell transplantation for severe T-cell immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:892–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Carlier F, Le Deist F, Morillon E, Taupin P, Gautier D, et al. Long-term T-cell reconstitution after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in primary T-cell-immunodeficient patients is associated with myeloid chimerism and possibly the primary disease phenotype. Blood. 2007;109:4575–4581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-029090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodbine L, Neal JA, Sasi NK, Shimada M, Deem K, Coleman H, et al. PRKDC mutations in a SCID patient with profound neurological abnormalities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2969–2980. doi: 10.1172/JCI67349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slatter MA, Bhattacharya A, Abinun M, Flood TJ, Cant AJ, Gennery AR. Outcome of boost haemopoietic stem cell transplant for decreased donor chimerism or graft dysfunction in primary immunodeficiency. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:683–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savic RM, Cowan MJ, Dvorak CC, Pai SY, Pereira L, Bartelink IH, et al. Effect of weight and maturation on busulfan clearance in infants and small children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1608–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czechowicz A, Kraft D, Weissman IL, Bhattacharya D. Efficient transplantation via antibody-based clearance of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Science. 2007;318:1296–1299. doi: 10.1126/science.1149726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Straathof KC, Rao K, Eyrich M, Hale G, Bird P, Berrie E, et al. Haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation with antibody-based minimal-intensity conditioning: a phase 1/2 study. Lancet. 2009;374:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson LE, Denny AW, Huh YO, Plunkett W, Keating MJ, Nelson JA. Natural killer cell activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with fludarabine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996;37:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s002800050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burroughs LM, Nemecek ER, Torgerson TR, Storer BE, Talano JA, Domm J, et al. Treosulfan-based conditioning and hematopoietic cell transplantation for nonmalignant diseases: a prospective multicenter trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;12:1996–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Railey MD, Lokhnygina Y, Buckley RH. Long-term clinical outcome of patients with severe combined immunodeficiency who received related donor bone marrow transplants without pretransplant chemotherapy or post-transplant GVHD prophylaxis. J Pediatr. 2009;155:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Burg M, Weemaes CM, Preijers F, Brons P, Barendregt BH, van Tol MJ, et al. B-cell recovery after stem cell transplantation of Artemis-deficient SCID requires elimination of autologous bone marrow precursor-B-cells. Haematologica. 2006;91:1705–1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myers LA, Patel DD, Puck JM, Buckley RH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency in the neonatal period leads to superior thymic output and improved survival. Blood. 2002;99:872–878. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mostoslavsky G, Fabian AJ, Rooney S, Alt FW, Mulligan RC. Complete correction of murine Artemis immunodeficiency by lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16406–16411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benjelloun F, Garrigue A, Demerens-de Chappedelaine C, Soulas-Sprauel P, Malassis-Séris M, Stockholm D, et al. Stable and functional lymphoid reconstitution in artemis-deficient mice following lentiviral artemis gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1490–1499. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]