Abstract

Generation 7 (G7) poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers with amine, acetamide, and carboxylate end groups were prepared to investigate polymer/cell membrane interactions in vitro. G7 PAMAM dendrimers were used in this study because higher generation of dendrimers are more effective in permeabilization of cell plasma membranes and in the formation of nanoscale holes in supported lipid bilayers than smaller, lower generation dendrimers. Dendrimer-based conjugates were characterized by 1H NMR, UV/Vis spectroscopy, GPC, HPLC, and CE. Positively charged amine-terminated G7 dendrimers (G7-NH2) were observed to internalize into KB, Rat2 and C6 cells at a 200 nM concentration. By way of contrast, neither negatively charged G7 carboxylate-terminated dendrimers (G7-COOH) nor neutral acetamide-terminated G7 dendrimers (G7-Ac) associated with the cell plasma membrane or internalized under similar conditions. A series of in vitro experiments employing endocytic markers cholera toxin subunit B (CTB), transferrin, and GM1-pyrene were performed to further investigate mechanisms of dendrimer internalization into cells. G7-NH2 dendrimers co-localized with CTB, however, experiments with C6 cells indicated that internalization of G7-NH2 was not ganglioside GM1 dependent. The G7/CTB co-localization was thus ascribed to an artifact of direct interaction between the two species. The presence of GM1 in the membrane also had no effect upon XTT assays of cell viability or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays of membrane permeability.

Keywords: PAMAM, dendrimer, endocytosis, nanoscale hole formation, cell membrane, ganglioside GM1

INTRODUCTION

Polycationic polymers such as poly(lysine)s, poly(ethyleneimine)s, diethylaminoethyl-dextrans, and poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers have demonstrated great potential to be exploited as gene transfer and drug delivery vectors.(1–9) Successful in vitro biomedical applications of the polycationic polymers have triggered a number of research groups to investigate the internalization mechanism of the macromolecules into cells. Efficient cross-membrane transport and membrane disruption were observed with a strong dependence on size (molecular weight) and surface groups of the polymers, as well as composition of model membranes.(10–14) Among those polycationic polymers, PAMAM dendrimers have attracted great scientific interest in the biomedical applications due to their excellent water-solubility and well-defined structure, molecular weight, and surface end groups. Demonstrated utility for practical applications, coupled with excellent monodispersity and chemical versatility, make PAMAM dendrimers an ideal material for exploring polymer-membrane interactions in greater detail.(6, 8–10, 13, 15)

The internalization mechanism of amine-terminated PAMAM dendrimers into cells has been explained as polycation-mediated endocytosis or leaky endocytosis.(10–14) In particular, co-localization studies with using choleratoxin subunit B (CTB) suggested that ganglioside GM1 played a major role in the initial interaction with the cell membrane and the subsequent internalization process for EA.hy 926 cells and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.(16) Furthermore, inhibition of internalization by methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) suggested that a lipid-raft mediated process may be a primary pathway for PAMAM dendrimer internalization into the cells. Subsequent studies with HeLa and HepG2 cells did not show an effect from MβCD but instead increased uptake and transfection efficiency were observed as a function of caveolin 1 expression.(17) These results were particularly interesting in light of other studies that had identified an “adsorptive” endocytosis that might involve a specific membrane component for B16f10 melanoma cells(18) which are also known to contain GM1.(19) However, the generality of a caveolae-based endocytosis mechanism is called into question by studies on Caco-2 cells which support a clathrin-based mechanism, not a caveolae-mediated mechanism.(20) In addition, studies on A549 cells indicate the process is not either clathrin or caveolae based.(21)

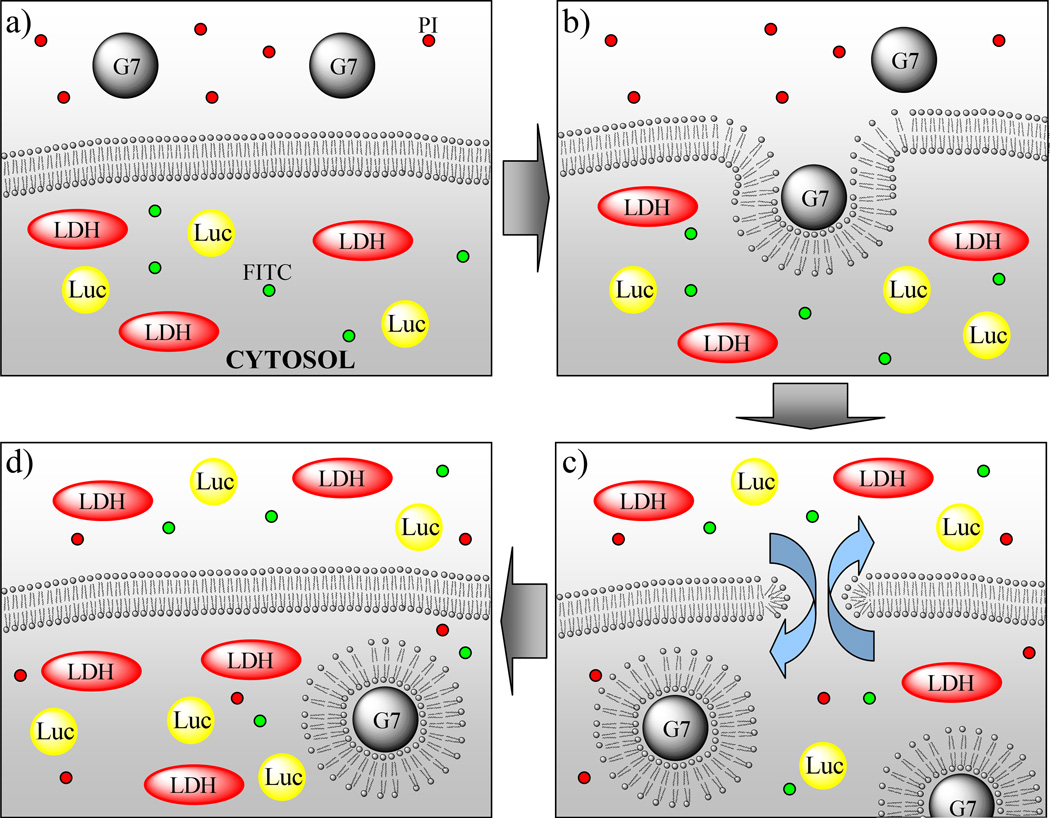

An alternative to endocytic mechanisms of uptake is direct physical disruption of the membrane and the formation of nanoscale holes causing plasma membrane permeability. AFM observations have revealed that polycationic polymers cause nanoscale hole formation, expansion of pre-existing defects, or membrane thinning depending on physical properties of polymers such as structure, size, and terminal groups, as well as membrane composition and phase.(6, 9, 22–25) Particularly, efficiency of hole formation in supported lipid bilayers induced by PAMAM dendrimers was concluded to be proportional to molecular weight (G7 > G5 > G3) as well as terminal end groups (amine > acetamide; i.e. charged > uncharged) of the dendrimers. Recent studies across a broad variety of cationic nanomaterials suggests that surface area is the single best correlate.(26) This observation agrees with in vivo studies carried out by Oberdörster et al.(27) AFM studies using supported lipid bilayers were consistent with our in vitro results exploring cell membrane permeability and dendrimer internalization.(6, 8, 9) Employing two tumor cell lines, KB and Rat2, cytosolic enzyme (LDH and luciferase) leakage, dendrimer internalization, and small molecule diffusion in and out of the cells were observed as a result of incubation with positively charged G7 PAMAM dendrimers as illustrated in Figure 1. We thus concluded that the cellular level data for the interaction of cationic PAMAM dendrimers with cell membranes was consistent with induction of nanoscale hole formation and that this process may be related to the internalization of these materials into the cell and/or the membrane permeability measured by dye diffusion and LDH assays.(6, 8, 9)

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the proposed nanoscale hole formation mechanism induced by positively charged PAMAM dendrimers. The data supporting this schematic summary is presented in this paper as well as in our previous reports.

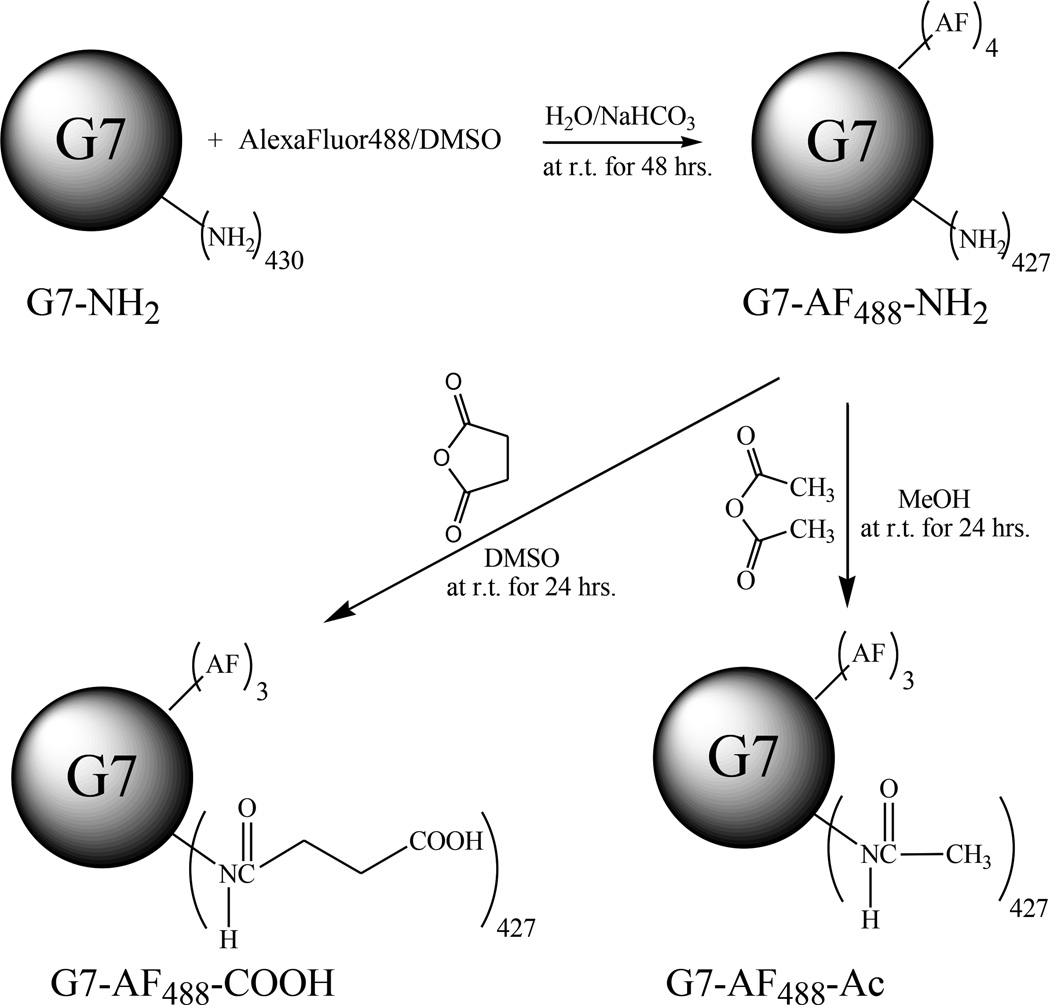

Considering the recent reports on endocytic internalization(16–21) and nanoscale hole formation,(6, 8, 9, 26) we decided to investigate the role of GM1 in the interaction of PAMAM dendrimers with cells. Experiments were designed probing the roles of GM1 in endocytosis and/or nanoscale hole formation. Experiments to test other key hypothesis such as clathrin pathways were also explored. For this study, G7 PAMAM conjugates were chosen because of their effectiveness in terms of both endocytosis and cell membrane disruption and because they had been observed to cause membrane permeability even at 4 °C.(6, 8, 9, 28, 29) Three different types of G7 PAMAM dendrimer-AlexaFluor®488 conjugates (amine, acetamide, and carboxylate terminated) were synthesized and characterized (Figure 2). The conjugates were then tested in vitro to explore dendrimer/cell interactions. The key findings in this paper are: 1) no evidence is found for a GM1 dependence of G7 PAMAM dendrimer with respect to internalization via endocytosis or nanoscale hole formation 2) the presence of GM1 in the membrane does not play a role in cell viability assays as measured by XTT 3) the presence of GM1 in the membrane does not play a role in plasma membrane permeability assays as measured by LDH.

Figure 2.

Synthetic routes for G7 PAMAM dendrimer conjugates with various surface end groups.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

G7 and G5 PAMAM dendrimers were synthesized at the Michigan Nanotechnology Institute for Medicine and Biological Sciences and purified using ultrafiltration and dialysis before use. Alexa Fluor®488 carboxylated, succinimidyl ester (AF488) was supplied by Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and used without further purification. Tranferrin from human serum labeled by AlexaFluor®546 (TF-AF546), recombinant cholera toxin subunit B-Alexa Fluor®647 conjugate (CTB-AF647), and LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (LysoTracker) were provided by Molecular Probes. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), and GM1-pyrene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used without further purification. Materials for native PAGE were obtained from Invitrogen. All other chemicals were acquired from Aldrich and used as received. Water used in this work was purified by Milli-Q Plus 185 system and had a resistivity higher than 18.0 MΩ/cm.

Preparation of PAMAM Dendrimer Conjugates and Their Surface Modification

Two milligrams of AF488 (6.20 µM, 5 times excess to G7) dissolved in 400 µL DMSO were conjugated to 68 mg of the purified G7 PAMAM dendrimers (1.25 µM) under the presence of 2 mL of 1 M NaHCO3 at room temperature for 48 hrs. The resulting reaction mixture was then dialyzed in water for 2 days and lyophilized for 2 days, followed by 5 times of ultrafiltration with water using an 80,000 molecular weight cut-off membrane at 21 °C, 5000 rpm for 30 min each. Sixty milligrams of a yellowish powder (G7-AF488-NH2) were finally obtained (yield: 86%). The average number of AF488 dye molecules present was determined by 1H NMR and/or GPC. The materials used in these studies varied from 2.4 – 4 AF488 per dendrimer. Twenty-two milligrams of G7-AF488-NH2 were allowed to react with 12 µL of acetic anhydride (50% mol excess to the conjugate) in 1.5 mL MeOH as a solvent at room temperature for 24 hrs. The reaction mixture was then purified by ultrafiltration at the same condition above with PBS (w/o Ca2+, Mg2+) and water subsequently 5 times for each. After lyophilization for 2 days, 16.25 mg of a yellowish powder (G7-AF488-Ac) was obtained (yield: 63%). Twenty milligrams of G7-AF488-NH2 were also allowed to react with 11 mg succinic anhydride (50% excess to the conjugate) in 1.5 mL DMSO at room temperature for 24 hrs followed by ultrafiltration and lyophilization at the same condition used for preparation of G7-AF488-Ac. A yellowish powder (18.8 mg) was obtained (G7-AF488-COOH, yield: 67%). The synthetic routes for the three different conjugates are summarized in Figure 2. In addition, G5 PAMAM dendrimers used in the XTT assay (Figure 3) were also conjugated with 6-carboxy-tetramethylrhodamine (6-TAMRA) followed by acetylation as described earlier.(30)

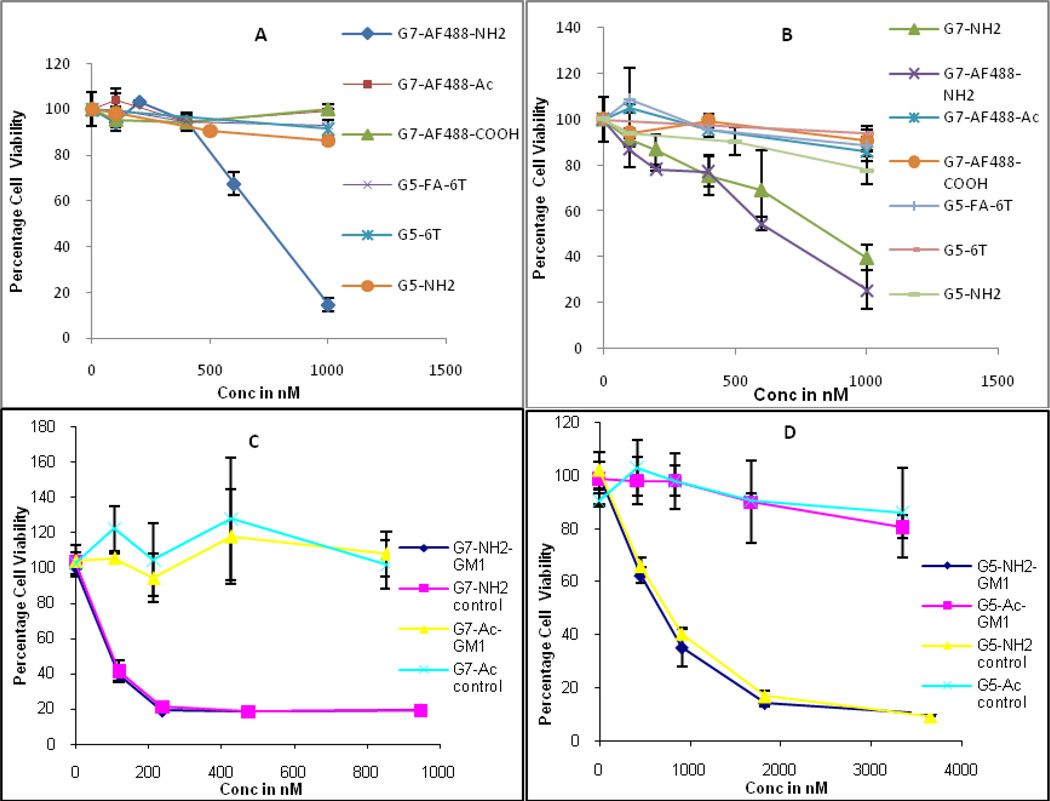

Figure 3.

Percentage viability as measured by XTT assay when cells are treated with various G5 and G7 PAMAM dendrimers: a) KB cells, b) RAT-2 cells, c) C6 cells, and d) C6 cells. FA = folic acid. 6T = 6-Tamra.

Characterization of the Prepared PAMAM Based Conjugates: UV/Vis and 1H NMR Spectroscopy

UV/Vis spectra of the G7 PAMAM conjugates were measured on Perkin Elmer UV/Vis spectrometer Lambda 20 (Wellesley, MA). Molar extinction coefficients of the dendrimer conjugates were also calculated by plotting maximum absorbance values against conjugate concentrations at 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL using the Lambert-Beer law (Table 1). 1H NMR spectra were also taken in D2O and were used to provide integration values for structural analysis using a Bruker AVANCE DRX 500 instrument.(31)

Table 1.

Molar extinction coefficients, molar masses, and polydispersity indices of the G7 conjugates

| Conjugates | Molar extinction coeff. (M−1cm−1)a |

Theoretical Molar Massb |

Molar Mass (Mn)c |

Polydispersity (Mw/Mn) |

HPLC Peak Width at Half-heightc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G7-NH2 | N/A | 97,020 | 97,000 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 0.52 |

| G7-AF488-NH2 | 171,100 | 99,137 | 99,600 | 1.38 ± 0.03 | 0.62 |

| G7-AF488-Ac | 147,130 | 116,903 | 116,300 | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 0.49 |

| G7-AF488-COOH | 122,520 | 141,437 | 138,500 | 1.08 ± 0.02 | 0.57 |

Molar extinction coefficients were obtained from Lambert-Beer equation by plotting λmax against corresponding concentrations of a conjugate (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL). R2 values of the linear regressions were 0.9966 – 0.999. The coefficients were calculated based on the UV characteristic peaks of conjugated AF488 at 497 nm.

Calculated from the measured molecular weight of starting G7-NH2 by assuming that the G7 PAMAM dendrimers have 4 AF488 moieties per dendrimer and 427 surface terminal groups according to the previously reported curve fit.(30)

Measured by GPC (Mn Number average molecular weight, Mw Weight average molecular weight).

Obtained from HPLC chromatograms (Figure 4).

Characterization of the Prepared PAMAM Based Conjugates: GPC and HPLC

The molar mass moments and molar mass distribution of each polymer sample were measured using gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The number average molecular weight (Mn) and polydispersity index (PDI), a commonly used measure of the breadth of the molar mass distribution defined as the ratio of the weight and number average molecular weights (Mw/Mn), of individual samples are listed in Table 1. GPC experiments were performed using an Alliance Waters 2690 separation module (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) equipped with a Waters 2487 UV absorbance detector (Waters Corp.), a Wyatt Dawn DSP laser photometer (Wyatt Technology Corp., Santa Barbara, CA), an Optilab DSP interferometric refractometer (Wyatt Technology Corp.), and TosoHaas TSK-Gel Guard PHW 06762 (75×7.5 mm, 12 µm), G 2000 PW 05761 (300 × 7.5 mm, 10 µm), G 3000 PW 05762 (300 × 7.5 mm, 10 µm), and G 4000 PW (300 × 7.5 mm, 17 µm) columns. A detailed procedure of the GPC measurement was described elsewhere.(9, 31)

The reverse-phase (RP) HPLC system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) consisting of a System GOLD 126 solvent module, a model 507 autosampler equipped with a 100 µL loop, and a model 166 UV detector were used in this study as well. A Jupiter C5 silica-based RP-HPLC column (250 × 4.6 mm, 300 Å) was purchased from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). Two Phenomenex Widepore C5 safety guards (4 × 3 mm) were also installed ahead of the Jupiter column. The mobile phase for elution of G7-AF488 dendrimer conjugates with different terminal groups was a linear gradient beginning from 100:0 (v/v) water/acetonitrile (ACN) to 50:50 (v/v) water/ACN at a flow rate of 1 mL/min for 40 min. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 0.14 wt % concentration in water as well as in ACN was used as counter-ions to make the dendrimer surfaces hydrophobic. All the samples were dissolved into the aqueous mobile phase (water containing 0.14% TFA) at the concentration of 1 mg/mL. The detection of eluted samples was performed at 210 nm. The analysis was performed using Beckman's System GOLD Nouveau software.(32)

Characterization of the Prepared PAMAM Based Conjugates: Capillary Electrophoresis (CE)

An Agilent Technologies (Waldbronn, Germany) CE instrument was used in this work. Unmodified quartz capillaries were purchased from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ, USA). The voltage was kept at 20 kV. On-capillary UV diode-array detection was used, operating at wavelengths of 210 nm, 250 nm, 280 nm and 495 nm. Samples were introduced by hydrodynamic injection at a pressure of 50 mbar.

For analysis of G7-AF488 conjugates with amino and acetamide terminal groups, silanized capillaries (i.d. 100 µm) with total length of 48.5 cm and effective length of 40 cm were employed following previous literature.(33) G7-AF488-NH2 and G7-AF488-Ac conjugates were dissolved in pH 2.5 phosphate buffer and the sample solutions were adjusted to pH 2.5 using 0.1 M phosphoric acid to give a concentration of 1 mg/ml. All the conjugates contained 0.05 mg/mL 2,3-diaminopyridine (2,3-DAP) as an internal standard.

For analysis of G7-AF488 conjugate with carboxyl terminal groups, bare silica capillaries (i.d. 75 µm) with total length of 64.5 cm and effective length of 56 cm were used for the characterization of G7-AF488-COOH conjugates. The capillary temperature was maintained at 20 °C. Before use, the uncoated silica capillary was pretreated by rinsing with 1 M NaOH (15 min), deionized water (Purchased from Agilent) (15 min) and running buffer (15 min).(33) Before each injection, the capillary was rinsed with a similar sequence of each eluent. 20 mM borate buffer (pH 8.3) was used as the running buffer. G7-AF488-COOH conjugates were dissolved in the running buffer and the sample’s pH was adjusted to 8.3 with 20 mM sodium tetraborate solution to get a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. 4-Methoxybenzyl alcohol (MBA) (0.05 mg/mL) was used as a neutral marker.

Cell Lines

The KB, Rat2, and C6 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and grown continuously as a monolayer at 37 °C, and 5% CO2. The KB cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). The Rat2 and C6 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany). The RPMI 1640 and DMEM media were supplemented with penicillin (100 units/mL), streptomycin (100 µg/mL), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine calf serum (FBS) before use.

XTT Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity of the dendrimer conjugates used in this study was assessed by the overall activity of mitochondrial dehydrogenase by 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) assay (Cell Proliferation Kit II, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). KB, Rat2, and C6 cell lines (at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/well) were prepared as monolayers in 96 well plates, followed by incubation with dendrimers in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with Ca2+ and Mg2+ at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 4.5 hrs (2 h for C6 cells). Polymer solutions (supernatants) were then removed, followed by washing with PBS twice. Mitochondrial activities of the cells were spectrophotometrically measured at 492 nm using a Spectra Max 340 ELISA Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cell viability was then calculated based on optical density (OD) from untreated cells.

LDH Membrane Permeability Assay

Membrane permeability was tested via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage using the LDH assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The activity of LDH in extracellular media is taken as a measure of membrane porosity. C6 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 96 well plates for overnight incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Dendrimers diluted in 100 µL PBS (w/ Ca2+, Mg2+) was added at specified concentrations into the 96 well plates and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 hrs after which the supernatant was removed and 50 µL was taken for the LDH assay (throughout the experiment boundary wells were not used). LDH activity was spectrophotometrically measured at 490 nm using an ELISA reader.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

A concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL of KB and Rat2 cells was seeded on MatTek glass bottom petri dishes (35 mm) and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 24 hrs. The cell culture medium was removed and 2 mL of each dendrimer-AF488 conjugates in PBS (w/ Ca2+, Mg2+) solution was added into the appropriate dish. The dishes were incubated with added solutions either at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 hr or at 4 °C. For the low temperature experiment, cells were pre-incubated at 4 °C for 10 min before adding the dendrimer solutions. The conjugate-containing solutions were removed and the resulting cell monolayer was washed with PBS at least three times. Cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde in the PBS (w/ Ca2+, Mg2+) at room temperature for 10 min, followed by washing with PBS twice.

For co-localization studies of dendrimers with CTB and transferrin on KB and Rat2 cells, dendrimer solutions were pre-mixed with markers, resulting in final concentrations of 200 nM, 10 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL for G7-AF488-NH2, CTB-AF647, and TF-AF546, respectively. The mixed solutions were then added to KB and Rat2 cells and the cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 hr.

For co-localization studies of CTB and G7-NH2 dendrimers on C6 cells, cells were seeded in Fisherbrand 2 well microscope cover glass # 1.5 at 2.5 × 105 cells/mL density, with 1 mL complete media in each well. Cells were allowed to attach to the surface for 4 hrs after which wells were washed with PBS (w/ Ca2+, Mg2+) and then overnight incubated with media (w/o serum) containing GM1-pyrene. Cells were then treated with 5 µg/mL CTB-AF647 for 1 hr or 500 nM G7-AF488-NH2- for 2 hrs, washed with PBS, and imaged in PBS solution.

For co-incubation of KB cells with G7-AF488-NH2 and fully acetylated G5 PAMAM-6-TAMRA conjugates (G5-6T-Ac),(34) KB cells were incubated with 100, 200, and 400 nM G7-AF488-NH2 at 37 °C for 30 min followed by addition of 1 µM G5-6T-Ac with additional incubation for 30 min.

Confocal and differential interference contrast (DIC) images were taken on an Olympus FV-500 confocal microscope using either a 60X, 1.5 NA or a 100X, 1.4 NA oil immersion objective. For the confocal images using three different AlexaFluors, the 488 nm line of an argon ion laser (for dendrimer conjugates), 543 nm line of a HeNeG laser (for transferrin and LysoTracker), or 633 nm line of a HeNeR laser (for cholera toxin) was used for excitation and the emission was filtered at 505–525, 560–600, 660 IF nm, respectively. Percentages of overlapping between two markers in the confocal images were quantified using Metamorph offline software version 6-3r7 provided by Molecular Devices (Downingtown, PA).

RESULTS

Synthesis and Characterization of G7 PAMAM/AlexaFluor 488 Conjugates with Various Surface End Groups

G7 PAMAM dendrimers were conjugated with AF488 dye to allow confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) studies. AF488 was chosen for this study because this fluorophore is known to exhibit brighter fluorescence and greater photostability than other spectrally similar fluorophores (300% more photostable than fluorescein (FITC) at 90 sec. exposure) as well as greater pH insensitivity between pH 4.0 and 10.0.(35) The synthesis scheme for the conjugates is illustrated in Figure 2. 1H NMR spectra for all three conjugates are provided in the supplementary material (Figure S1). After conjugation with AF488, characteristic peaks for the conjugated dyes molecules appear in the range of δ 6.8–8.4 ppm. The 1H NMR spectrum of G7-AF488-Ac (Figure S1c) is consistent with the previously published spectra using G5 PAMAM.(31) UV/Vis spectra reveal that maximum absorbance of AF488 shifted from 495 to 497 nm after conjugation with the dendrimer. Calculated molar extinction coefficients decrease with the increase of molecular weights of the conjugates providing a rough guide when the surface modification from primary amine end groups to acetamide and carboxylate end groups is successfully performed (see Table 1).

HPLC chromatograms of the prepared G7 PAMAM dendrimer conjugates are provided in supplementary materials (Figure S2). All the conjugates exhibit a single peak and it is notable that no peak is present for free AF488 in the chromatograms. The peak widths at half-height of all the dendrimers are ranged from 0.49 to 0.62 min indicate that the dendrimer conjugates are relatively monodisperse compared to other types of condensation polymers with molecular weights of > 100,000 g/mol. This is consistent with GPC results presented in Table 1.(32) In order to provide an even more stringent assessment of polymer homogeneity, the same materials were characterized using CE.(9, 33, 36–38) The G7-NH2 dendrimer exhibits multiple peaks which persists, with a change in relative magnitude, after conjugation with AF488 (Figure S3b). After surface modification with acetamide and carboxylate groups is performed, the dendrimer conjugates produce sharper peaks although a multiple peak structure is still apparent for G7-AF488-Ac.

Cytotoxicity of Dendrimer Conjugates as Measured by XTT Assays

The cytotoxicity of the G7 PAMAM conjugates on KB, Rat2, and C6 cells in vitro was explored using XTT assay (Figure 3). The KB cell line, a variant of the human HeLa line, and the Rat2 cell line, a dermal fibroblast from Fisher Rat, were selected because they are adherent and robust cell lines enabling us to employ various biological techniques. The C6 cell line was selected because it contains caveolin-1 but lacks GM1 in the plasma membrane.

Amine terminated G7 PAMAM dendrimers show a degree of cytotoxicity (~20% toxicity) starting at a concentration of ~400 nM whereas G5 PAMAMs are not cytotoxic at a concentration as high as 1 µM in both KB and Rat2 cells. These results are consistent with our previous report which concluded the cytotoxicity of the PAMAM dendrimers is highly dependent on size of the macromolecules.(9) Surface modification of the starting dendrimers dramatically reduces their cytotoxicity. As shown in Figure 3a and 3b, G7-AF488-Ac, G7-AF488-COOH, G5-6T-FA (cancer cell targeting dendritic nanodevices), and G5-6T-Ac do not show any significant toxic effect on the both cell lines at the concentration range used in the experiment. The effect of the presence of GM1 in the cell plasma membrane on cytotoxicity was explored using the C6 cell line (Figure 3, panel C and D). The C6 cells exhibited a greater sensitivity to G5-NH2 and G7-NH2 exposure but no differential effect was observed as a function of the presence of GM1 in the membrane.

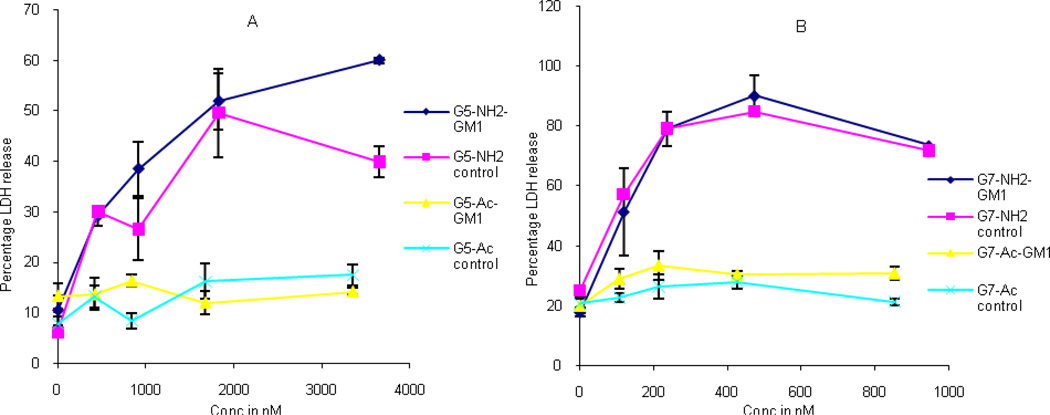

The Induction of Membrane Permeability as Measured by LDH assays

The effect of GM1 on the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was explored using C6 cells (Figure 4). LDH release was independent of the presence of GM1 in the cell plasma membrane for exposure to G5-NH2 and G7-NH2. By way of contrast, the acetylated forms of the dendrimer, G5-Ac and G7-Ac, did not exhibit a concentration dependent release of LDH.

Figure 4.

Percentage LDH release of C6 cells when treated with a) G5 and b) G7 PAMAM dendrimers.

CLSM Observation: Surface Group Dependence on Dendrimer Internalization

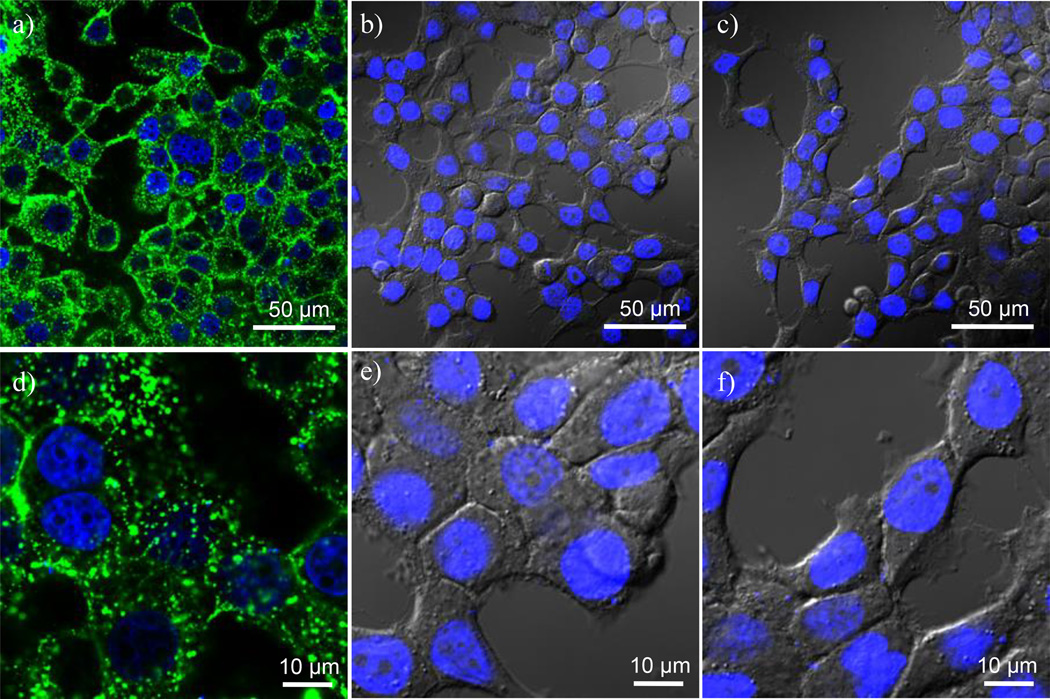

Figure 5 shows confocal images of Rat2 cells after exposure to G7-AF488-NH2, G7-AF488-Ac, and G7-AF488-COOH at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 hr. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI and appear as blue fluorescence in the images. Figure 5d, 5e, and 5f are digitally zoomed-in images of Figure 5a, 5b, and 5c, respectively. As shown in Figure 5a and 5d, and confirmed by z-stack images, G7-AF488-NH2 readily internalizes into the cells resulting in a punctate distribution of strong green fluorescence. On the other hand, surface modified dendrimers (G7-AF488-Ac and G7-AF488-COOH) do not interact with cell membrane or internalize into the cells (Figure 5b, c, e, and f). This is consistent with the XTT and LDH assay results shown in Figures 3 and 4 as well as previously published AFM results indicating that G7-NH2 is the most active with supported lipid bilayers.(24, 25) These results stand in stark contrast to CHARM/MD studies that suggest that all three dendrimers should interact strongly with a lipid bilayer.(39, 40) To clearly show cell morphology, differential interference contrast (DIC) images of the cells incubated with G7-AF488-Ac and G7-AF488-COOH were overlapped with confocal fluorescence images in those images. Similar results were obtained using KB cells as well (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Confocal images of Rat2 cells after exposure to a) G7-AF488-NH2, b) G7-AF488-Ac, and c) G7-AF488-COOH at 37 °C for 1 hr. The concentration of the dendrimer conjugates was at 200 nM. Images e), f), and g) are digitally enlarged images of a), b), and c), respectively. Images b), c), e), and f) are overlays of confocal and DIC images. Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI resulting in blue fluorescence in the images.

CLSM Observation: Effect of Low Temperature on G7-NH2 Internalization

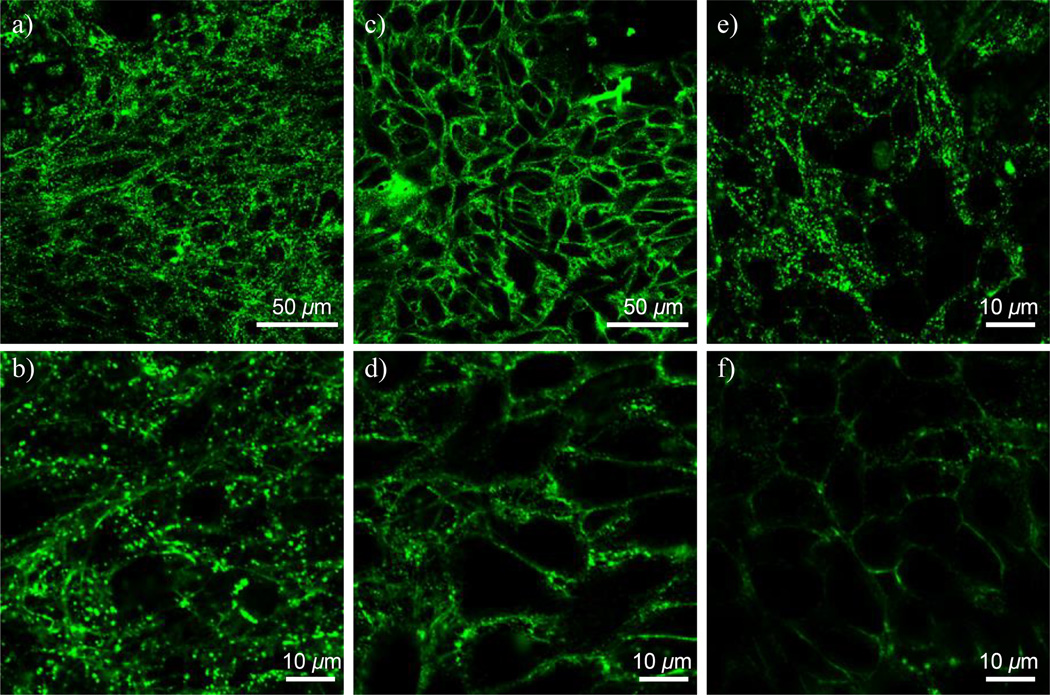

Figure 6 illustrates confocal images of Rat2 cells after incubation with G7-AF488-NH2 and G5-FITC-NH2 at both 37 °C and 4 °C. As shown in Figure 6e and f, G5-FITC-NH2 penetrates into the cells at 37 °C whereas they do not internalize but associate with cell plasma membranes at 4 °C, which is in good agreement with previously published images.(9) Although G7-AF488-NH2 internalization is reduced at the lowered temperature by ~60% as measured by FACS, the dendrimers internalize into the cells not only at 37 °C but also at 4 °C as shown in Figure 6a and 6b. It can be more clearly observed in the zoomed-in image (Figure 6d). Z-stack images of Figure 6d also confirm internalization of the dendrimers (data not shown). The intracellular distribution pattern of fluorescence in Figure 6d is slightly different from that of Figure 6b. Less punctate distribution of the dendrimers in the cytosol is observed in Figure 6d (the low temperature case) as compared intracellular distribution of the dendrimers in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Confocal images of Rat2 cells after incubation with G7-AF488-NH2 at a) 37 °C and c) 4 °C, both for 1 hr. Images b) and d) are enlarged images of a) and c), respectively. Concentration of the dendrimer conjugates were at 200 nM. Note that G7-AF488-NH2 penetrates into the cells even at the low temperature. Controls using G5-FITC-NH2 at e) 37 °C and f) 4 °C.

CLSM Observation: Intracellular Co-localization of G7-NH2 with Endocytic Markers

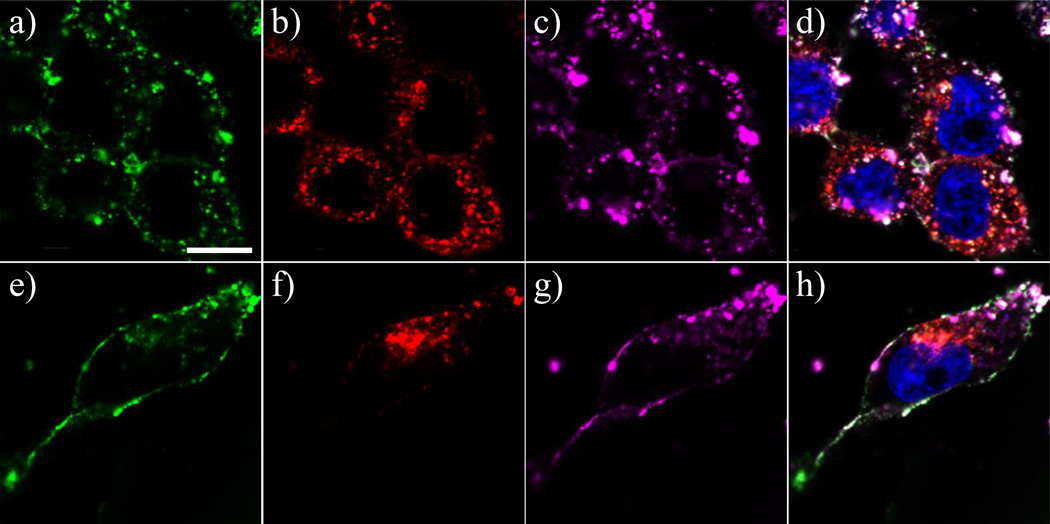

The generally reported endocytic pathways for large molecules such as biomedical polymers and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) include clathrin-dependent and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis.(2, 41) We employed commonly used endocytic markers, transferrin for clathrin dependent pathways and CTB for lipid raft-mediated endocytosis to explore the mechanism of dendrimer uptake.(41, 42) Direct observation of intracellular localization of the markers using CLSM was enabled by employing markers labeled by different AlexaFluors. As shown in Figure 7, G7-AF488-NH2 (green fluorescence) is co-localized with CTB-AF647 (purple fluorescence) whereas intracellular localization of TF-AF546 is different from those of dendrimers and CTB in both KB and Rat2 cells. The quantified pixel counts for overlapped pixels using Metamorph software indicate the co-localization between G7-AF488-NH2 and CTB-AF647 is 88% and 68% for KB and Rat2 cells, respectively. In contrast, co-localization as indicated by quantification of overlapped pixels for G7-AF488-NH2 and TF-AF546 was 10 and 17 % for KB and Rat2 cells, respectively.

Figure 7.

Confocal images of KB cells incubated for 1 h with a) 200 nM G7-AF488-NH2, b) 50 µg/mL transferrin-AlexaFluor 546 (TF-AF546), and c) 10 µg/mL cholera toxin subunit B-Alexa Fluor 647 (CTB-AF647) conjugates, and b) a merged image of those. Green, red, and purple fluorescence respectively represent G7-AF488-NH2, TF-AF546, and CTB-AF647. Images e), f), g), and h) are a data set of Rat2 cells at the same condition with KB cells. Note that dendrimers are co-localized intracellularly with CTB in the both cell lines. Bar: 10 µm.

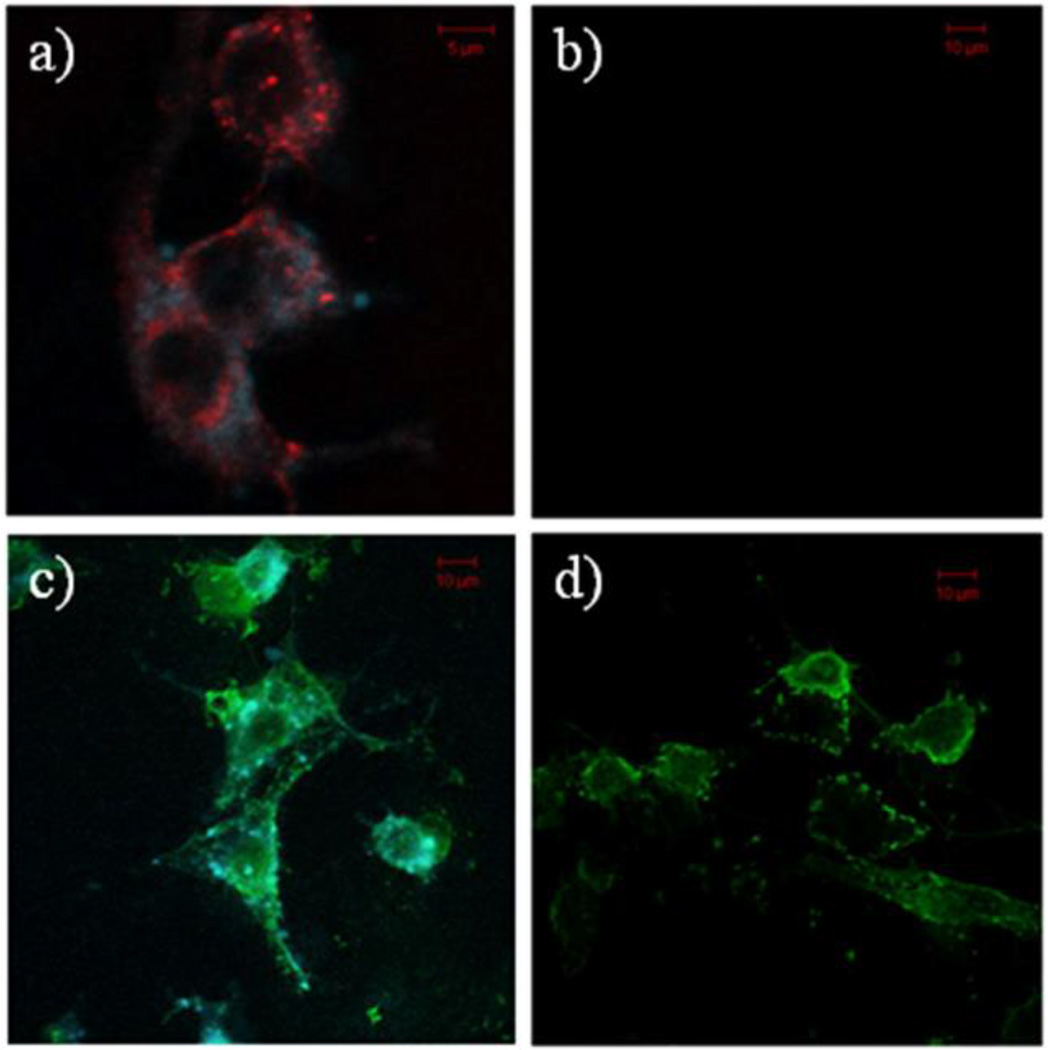

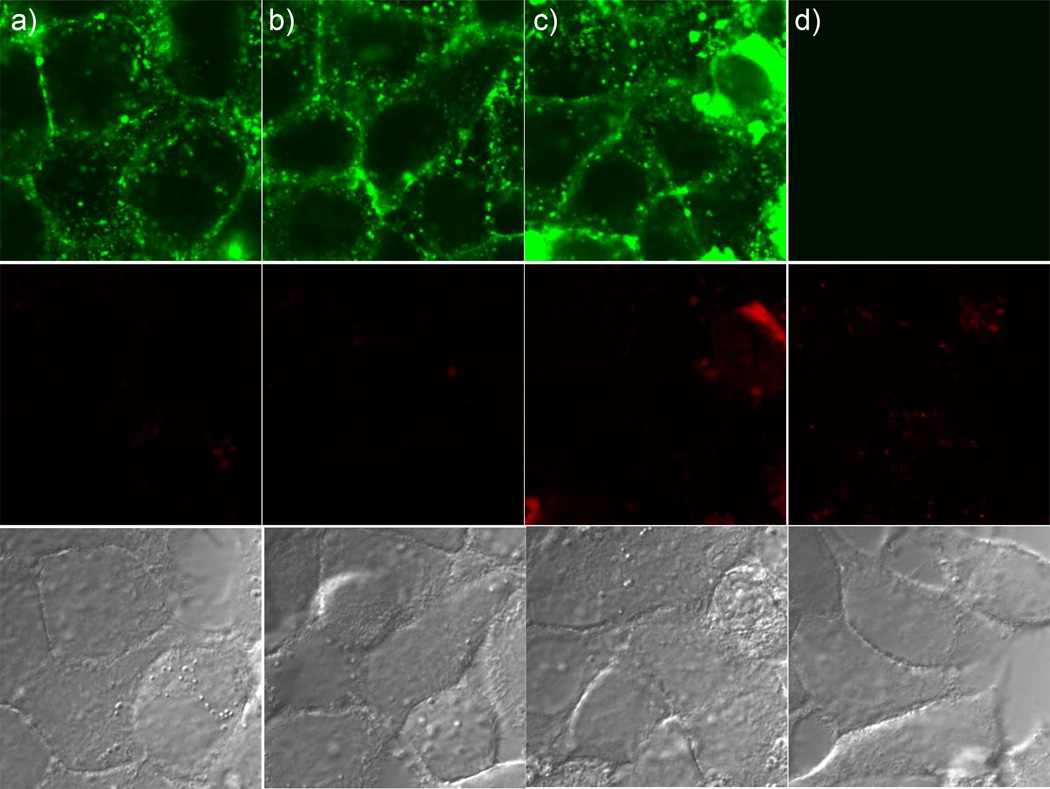

Co-localization with CTB is commonly taken as evidence for GM1 interactions and a raft mediated endocytosis mechanism.(41) In order to directly test this hypothesis, internalization of CTB and G7-NH2 was tested using C6 cells. In their native state, these cells contain little GM1 in the plasma membrane. However, GM1 can be added to the membrane via incubation. Consistent with previous reports in the literature,(43) CTB only internalized into C6 cells that had been pre-incubated with GM1. However, G7-NH2 internalized independent of the presence of GM1 in the plasma membrane (Figure 8). Recall that the results of both the XTT and LDH assays were independent of the presence of GM1 in the C6 cell plasma membrane (Figures 3 and 4). The interaction of G7-NH2 dendrimer and CTB was explored using native poly(acrylamide) gel electrophoresis employing Coommassie blue staining. The band associated with CTB was no longer present upon mixing the dendrimer with the CTB at ratios from 1:5 to 5:1.

Figure 8.

Confocal images of a) C6 cells having GM1-pyrene (blue) treated with Cholera toxin subunit B (CTB)-AF647(red), b) C6 cells without GM1 treated with CTB, c) C6 cells having GM1–pyrene (blue) treated with G7-NH2-AF488 (green) PAMAM dendrimer, and d) C6 cells without GM1 treated with G7 dendrimer. All incubations were for 1 h. CTB is internalized only when GM1 is present in the cell membrane. G7-NH2 dendrimer is internalized independent of the presence of GM1 in the cell membrane.

CLSM Observation: Diffusion of neutral dendrimers into cell?

Neutral dendrimers (G7-Ac and G5-Ac) do not interact with the cell membrane or internalize into the cell as indicated by LDH and XTT assays (Figures 3 and 4) and CLSM experiments (Figure 5). However, if holes of 5–25 nm were created in the membrane, G5-Ac might be expected to enter the cell via passive diffusion processes. Our previous studies have shown that LDH (135–140 kDa, ~4.3 nm diameter), propidium iodide, and fluorescein all diffusion across the membrane.(6) However, as illustrated in Figure 9, 100 nM G7-NH2 is sufficient to give substantial internalization of dendrimer but 1 µM G5-6T-Ac still gives no detectable internalization. Previous studies indicate the G7-NH2 should be about 8 nm in diameter and the G5-6T-Ac should be about ~ 4–7 nm in diameter.(24, 44)

Figure 9.

Confocal images of KB cells co-incubated for 1 h with a) 100 nM, b) 200 nM, and c) 400 nM G7-AF488-NH2 and 1 µM G5-6T-Ac. Image d) shows KB cells incubated with 1 µM G5-6T-Ac only. Note that red fluorescence should be detected if G7-AF488-NH2 induces diffusion of G5-6T-Ac into the cells. However no noticeable signal from G5-6T-Ac is observed. The first row: green fluorescence channel detecting G7-AF488-NH2, the second row: red fluorescence channel detecting G5-6T-Ac, and the third row: DIC images of each sample. Bar: 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

Dendrimer/membrane Interactions and Dendrimer Internalization

Amine-terminated (positively charged) G7 PAMAM dendrimers (G7-NH2) exhibit cytotoxicity (Figure 3), cause LDH leakage (Figure 4), and internalize into cells (Figures 5–8) at <200 nM concentrations whereas charge neutral and negatively charged G7 PAMAM dendrimers do not. This is interesting because negatively charged PAMAM dendrimers (G7-AF488-COOH), suggested as a potential drug delivery vectors,(45) do not bind or internalize into cells at these concentrations (Figure 5c and f). We previously reported that G7-NH2 PAMAM dendrimers caused more LDH leakage out of cells at 37 °C than G5-NH2 indicating that G7-NH2 is more effective in membrane permeabilization or dendroporation. Furthermore, G7-NH2 induces LDH leakage at 4 °C whereas G5-NH2 does not.(9) Confocal images also illustrate that G7-NH2 internalizes into the cells at 4 °C but G5-NH2 does not (Figure 9). One might argue that the enhanced LDH leakage is caused by cell death since G7-NH2 appears to be more cytotoxic than G5-NH2 (Figure 4). In our concentration range (200 nM), however, G7-NH2 exhibits minimal cytotoxic effects which are ~100% viability for KB and > 80% viability for Rat2. Consequently, the observed LDH assay and confocal data are taken as evidence for membrane permeabilization as opposed to cell death.

Low temperature has been used in a number of studies to investigate energy (or metabolic activities) dependency of proposed internalization mechanisms. Studies have been published for synthetic polymers and for CPPs.(41, 42, 46) The observation of G7-AF488-NH2 internalization at 4 °C can be explained by a number of possible mechanisms. One would be energy independent translocation mechanism as previously proposed for CPP internalization.(47) However, lowering temperature prevents G5-NH2 internalization and partially inhibits G7-NH2 internalization, indicating that dendrimer internalization is an energy dependent process. We will now consider two possible contributors to the energy-dependence of the nanoscale hole formation mechanism. First, the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the dendrimers may be responsible for the observed temperature dependence. Since the incubation temperature (4 °C) is lower than Tg of both G5 and G7 PAMAM dendrimers (14–16 °C),(48) chain flexibility of the dendrimer molecules should be substantially decreased. The decrease in dendrimer flexibility could impact the interaction with the plasma membrane creating a large barrier to micelle formation. Second, a phase change in the cell plasma membrane from the fluid phase (Lα) to low temperature gel phase (L*β)(49) would also inhibit nanoscale hole formation. It has recently been demonstrated using supported lipid bilayers that G7-NH2 dendrimers only cause nanoscale hole formation in fluid phase membranes.(23) This is consistent with other reports indicating the membrane fluidity is related to transport properties in epithelial cells.(50)

There are several energy dependent pathways proposed for polycationic polymers including endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits(51, 52) and endocytosis via lipid rafts or caveolae.(53, 54) For this study we employed transferrin which is a commonly used marker for clathrin-mediated endocytosis and CTB which is a commonly used marker for clathrin-independent lipid raft (or caveolae) mediated endocytosis.(41) G7-AF488-NH2 did not show substantial colocalization with transferrin (10% and 17% overlapping for KB and Rat2, respectively), indicating that G7-AF488-NH2 internalization is not related to the clathrin-dependent pathway. Instead significant colocalization of G7-AF488-NH2 with CTB-AF647 was observed (88% and 68% overlapping for KB and Rat2, respectively). Co-localization with CTB implies that G7-AF488-NH2 localizes in the cell with ganglioside GM1. However, G7-AF488-NH2 internalized into C6 cells independent of the presence of the GM1 and G7-AF488-NH2 did not co-localize with GM1-pyrene. This indicates that the co-localization observed by us and others(16) is probably related to a dendrimer-CTB interaction and is not related to GM1 interactions or a raft mediated endocytosis pathway. The LDH assays for C6 cells show no effect upon the presence or absence of GM1 indicating the GM1 is also not important for the mechanism of membrane permeabilization and nanoscale hole formation.

A substantial literature exists supporting polycationic endocytosis as a mechanism for the uptake of polycationic polymers into cells.(16, 41, 55–58) However, many inconclusive and contradictory experiments can be found in the literature and the details of the internalization mechanisms have remained elusive. In this paper, we provide direct evidence indicating a GM1-dendrimer interaction is not involved in G7-AF488-NH2 internalization. The best evidence supporting raft-mediated endocytosis for dendrimers, co-localization with CTB, is shown to instead result from a CTB-dendrimer interaction. Our results including nanoscale hole formation in supported lipid bilayers,(23–25) enzyme leakage and small molecule diffusion in and out of cells,(6, 9) and G7-AF488-NH2 internalization at 4 °C, do provide an alternative mechanism by which polycationic polymers, and nanoparticles more broadly,(26) may enter cells; the formation of nanoscale holes in the cell plasma membranes.(8) The data presented here, and published elsewhere by ourselves and others, does not indicate that the nanoscale hole mechanism should be considered as a replacement for endocytosis mechanisms. Rather, it suggests a competitive process in which both mechanisms are operative. The nanoscale hole hypothesis does provide a straightforward explanation for data that is inconsistent with the endocytosis mechanism, both in this paper and in polycationic polymer endocytosis literature more generally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by federal funds from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and BioEngineering (R01-EB005028).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

1H NMR, HPLC, and CE characterization data for dendrimer conjugates. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdallah B, Sachs L, Demeneix BA. Non-viral gene transfer: Applications in developmental biology and gene therapy. Biology of the Cell. 1995;85:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nori A, Kopecek J. Intracellular targeting of polymer-bound drugs for cancer chemotherapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2005;57:609–636. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patri AK, Majoros IJ, Baker JR. Dendritic polymer macromolecular carriers for drug delivery. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2002;6:466–471. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintana A, Raczka E, Piehler L, Lee I, Myc A, Majoros I, Patri AK, Thomas T, Mule J, Baker JR. Design and function of a dendrimer-based therapeutic nanodevice targeted to tumor cells through the folate receptor. Pharmaceutical Research. 2002;19:1310–1316. doi: 10.1023/a:1020398624602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies ER, Frechet JMJ. Dendrimers and dendritic polymers in drug delivery. Drug Discovery Today. 2005;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong S, Bielinska AU, Mecke A, Keszler B, Beals JL, Shi X, Balogh L, Orr BG, Baker JR, Banaszak Holl MM. The Interaction of Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) Dendrimers with Supported Lipid Bilayers and Cells: Hole Formation and the Relation to Transport. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2004;15:774–782. doi: 10.1021/bc049962b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong S, Hessler JA, Banaszak Holl MM, Leroueil PR, Mecke A, Orr BG. Physical Interactions of Nanoparticles with Biological Membranes: The Observation of Nanoscale Hole Formation. Chemical Health and Safety. 2006;13:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leroueil PR, Hong SY, Mecke A, Baker JR, Orr BG, Holl MMB. Nanoparticle interaction with biological membranes: Does nanotechnology present a janus face? Accounts of Chemical Research. 2007;40:335–342. doi: 10.1021/ar600012y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong SP, Leroueil PR, Janus EK, Peters JL, Kober MM, Islam MT, Orr BG, Baker JR, Holl MMB. Interaction of polycationic polymers with supported lipid bilayers and cells: Nanoscale hole formation and enhanced membrane permeability. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2006;17:728–734. doi: 10.1021/bc060077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang SB, Xu YM, Wang B, Qiao WH, Liu DL, Li ZS. Cationic compounds used in lipoplexes and polyplexes for gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;100:165–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain M, Shchepinov MS, Sohail M, Benter IF, Hollins AJ, Southern EM, Akhtar S. A novel anionic dendrimer for improved cellular delivery of antisense oligonucleotides. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;99:139–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jevprasesphant R, Penny J, Attwood D, D'Emanuele A. Transport of dendrimer nanocarriers through epithelial cells via the transcellular route. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;97:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jevprasesphant R, Penny J, Attwood D, McKeown NB, D'Emanuele A. Engineering of dendrimer surfaces to enhance transepithelial transport and reduce cytotoxicity. Pharmaceutical Research. 2003;20:1543–1550. doi: 10.1023/a:1026166729873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopatz I, Remy JS, Behr JP. A model for non-viral gene delivery: through syndecan adhesion molecules and powered by actin. Journal of Gene Medicine. 2004;6:769–776. doi: 10.1002/jgm.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu ZH, Li MY, Cui DF, Fei J. Macro-branched cell-penetrating peptide design for gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;102:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manunta M, Tan PH, Sagoo P, Kashefi K, George AJT. Gene delivery by dendrimers operates via a cholesterol dependent pathway. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:2730–2739. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manunta M, Nichols BJ, Tan PH, Sagoo P, Harper J, George AJT. Gene delivery by dendrimers operates via different pathways in different cells, but is enhanced by the presence of caveolin. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2006;314:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seib FP, Jones AT, Duncan R. Comparison of the endocytic properties of linear and branched PEIs, and cationic PAMAM dendrimers in B16f10 melanoma cells. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;117:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandyba AG, Kozlov AM, Somova OG, Dyatlovitskaya EV. A comparative study of sphingolipids in transplanted melanomas with high and low metastatic activity. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry. 2008;34:230–233. doi: 10.1134/s1068162008020131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitchens KM, Kolhatkar IB, Swaan PW, Ghandehari H. Endocytosis inhibitors prevent poly(amidoamine) dendrimer internalization and permeability across Ceco-2 cells. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2008;5:364–369. doi: 10.1021/mp700089s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perumal OP, Inapagolla R, Kannan S, Kannan RM. The effect of surface functionality on cellular trafficking of dendrimers. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3469–3476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mecke A, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. Membrane thinning due to antimicrobial peptide binding - An AFM study of MSI-78 in DMPC bilayers. Biophysical Journal. 2005;89:4043–4050. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mecke A, Lee D-K, Ramamoorthy A, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. Synthetic and Natural Polycationic Polymer Nanoparticles Interact Selectively with Fluid-Phase Domains of DMPC Bilayers. Langmuir. 2005;21:8588–8590. doi: 10.1021/la051800w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mecke A, Majoros I, Patri AK, Baker JR, Banaszak Holl MM, Orr BG. Lipid Bilayer Disruption by Polycationic Polymers: The Roles of Size and Chemical Functional Group. Langmuir. 2005;21:10348–10354. doi: 10.1021/la050629l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mecke A, Uppuluri S, Sassanella TJ, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A, Baker JR, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. Direct Observation of Lipid Bilayer Disruption by Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 2004;132:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leroueil PR, Berry SA, Duthie K, Han G, Rotello VM, McNerny DQ, Baker JR, Orr BG, Holl MMB. Wide varieties of cationic nanoparticles induce defects in supported lipid bilayers. Nano Letters. 2008;8:420–424. doi: 10.1021/nl0722929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113:823–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karoonuthaisiri N, Titiyevskiy K, Thomas JL. Destabilization of fatty acid-containing liposomes by. polyamidoamine dendrimers. Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces. 2003;27:365–375. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z-Y, Smith BD. High-Generation Polycationic Dendrimers Are Unusually Effective at Disrupting Anionic Vesicles: Membrane Bending Model. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2000;11:805–814. doi: 10.1021/bc000018z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patri AK, Myc A, Beals J, Thomas TP, Bander NH, Baker JR. Synthesis and in vitro testing of J591 antibody-dendrimer conjugates for targeted prostate cancer therapy. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2004;15:1174–1181. doi: 10.1021/bc0499127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majoros IJ, Keszler B, Woehler S, Bull T, Baker JR. Acetylation of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers. Macromolecules. 2003;36:5526–5529. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Islam MT, Shi XY, Balogh L, Baker JR. HPLC separation of different generations of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers modified with various terminal groups. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:2063–2070. doi: 10.1021/ac048383x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi XY, Lesniak W, Islam MT, Muniz MC, Balogh LP, Baker JR. Comprehensive characterization of surface-functionalized poly (amidoamine) dendrimers with acetamide, hydroxyl, and carboxyl groups. Colloids and Surfaces a-Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2006;272:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas TP, Myaing MT, Ye JY, Candido K, Kotlyar A, Beals J, Cao P, Keszler B, Patri AK, Norris TB, Baker JR. Detection and analysis of tumor fluorescence using a two-photon optical fiber probe. Biophysical Journal. 2004;86:3959–3965. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banks PR, Paquette DM. Comparison of 3 Common Amine Reactive Fluorescent-Probes Used for Conjugation to Biomolecules by Capillary Zone Electrophoresis. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1995;6:447–458. doi: 10.1021/bc00034a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi XY, Banyai I, Lesniak WG, Islam MT, Orszagh I, Balogh P, Baker JR, Balogh LP. Capillary electrophoresis of polycationic poly(amidoamine) dendrimers. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2949–2959. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi XY, Majoros IJ, Patri AK, Bi XD, Islam MT, Desai A, Ganser TR, Baker JR. Molecular heterogeneity analysis of poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-based mono- and multifunctional nanodevices by capillary electrophoresis. Analyst. 2006;131:374–381. doi: 10.1039/b515624f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi XY, Patri AK, Lesniak W, Islam MT, Zhang CX, Baker JR, Balogh LP. Analysis of poly(amidoamine)-succinamic acid dendrimers by slab-gel electrophoresis and capillary zone electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2960–2967. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly CV, Leroueil PR, Nett EK, Wereszczynski JM, Baker JR, Orr BG, Holl MMB, Andricioaei I. Poly(amidoamine) dendrimers on lipid bilayers I: Free energy and conformation of binding. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2008;112:9337–9345. doi: 10.1021/jp801377a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly CV, Leroueil PR, Orr BG, Holl MMB, Andricioaei I. Poly(amidoamine) dendrimers on lipid bilayers II: Effects of bilayer phase and dendrimer termination. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2008;112:9346–9353. doi: 10.1021/jp8013783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foerg C, Ziegler U, Fernandez-Carneado J, Giralt E, Rennert R, Beck-Sickinger AG, Merkle HP. Decoding the entry of two novel cell-penetrating peptides in HeLa cells: Lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and endosomal escape. Biochemistry. 2005;44:72–81. doi: 10.1021/bi048330+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV, Lebleu B. Cell-penetrating peptides - A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:585–590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spiegel S. Insertion of Ganglioside GM1 into Rat Glioma C6 Cells Renders Them Susceptible to Growth-Inhibition by the B-Subunit of Cholera-Toxin. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1988;969:249–256. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prosa TJ, Bauer BJ, Amis EJ, Tomalia DA, Scherrenberg R. A SAXS study of the internal structure of dendritic polymer systems. Journal of Polymer Science Part B-Polymer Physics. 1997;35:2913–2924. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiwattanapatapee R, Carreño-Gómez B, Malik N, Duncan R. Anionic PAMAM Dendrimers Rapidly Cross Adult Rat Intestine In Vitro: A Potential Oral Delivery System? Pharmaceutical Research. 2000;17:991–998. doi: 10.1023/a:1007587523543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorén PEG, Persson D, Esbjorner EK, Goksor M, Lincoln P, Norden B. Membrane binding and translocation of cell-penetrating peptides. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3471–3489. doi: 10.1021/bi0360049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction technology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2002;13:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uppuluri S, Morrison FA, Dvornic PR. Rheology of dendrimers. 2. Bulk polyamidoamine dendrimers under steady shear, creep, and dynamic oscillatory shear. Macromolecules. 2000;33:2551–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janiak MJ, Small DM, Shipley GG. Temperature and compositional dependence of the structure of hydrated dimyristoyl lecithin. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:6068–6078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Grimellec C, Friedlander G, Elyandouzi E, Zlatkine P, Giocondi MC. Membrane Fluidity and Transport-Properties in Epithelia. Kidney International. 1992;42:825–836. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vendeville A, Rayne F, Bonhoure A, Bettache N, Montcourrier P, Beaumelle B. HIV-1 Tat enters T cells using coated pits before translocating from acidified endosomes and eliciting biological responses. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15:2347–2360. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmid SL. Clathrin-coated vesicle formation and protein sorting: An integrated process. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1997;66:511–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown DA, London E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parton RG, Richards AA. Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: New insights and common mechanisms. Traffic. 2003;4:724–738. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Apodaca G. Endocytic traffic in polarized epithelial cells: Role of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Traffic. 2001;2:149–159. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fischer R, Kohler K, Fotin-Mleczek M, Brock R. A stepwise dissection of the intracellular fate of cationic cell-penetrating peptides. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:12625–12635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bieber T, Meissner W, Kostin S, Niemann A, Elsasser HP. Intracellular route and transcriptional competence of polyethylenimine-DNA complexes. Journal of Controlled Release. 2002;82:441–454. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.