Abstract

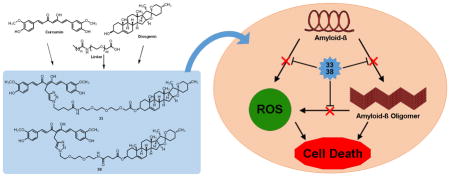

In an effort to combat the multifaceted nature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression, a series of multifunctional, bivalent compounds containing curcumin and diosgenin were designed, synthesized, and biologically characterized. Screening results in MC65 neuroblastoma cells established that compound 38 with a spacer length of 17 atoms exhibited the highest protective potency with an EC50 of 111.7 ± 9.0 nM. A reduction in protective activity was observed as spacer length was increased up to 28 atoms and there is a clear structural preference for attachment to the methylene carbon between the two carbonyl moieties of curcumin. Further study suggested that antioxidative ability and inhibitory effects on amyloid-β oligomer (AβO) formation may contribute to the neuroprotective outcomes. Additionally, compound 38 was found to bind directly to Aβ, similar to curcumin, but did not form complexes with the common biometals Cu, Fe, and Zn. Altogether, these results give strong evidence to support the bivalent design strategy in developing novel compounds with multifunctional ability for the treatment of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, bivalent strategy, natural products, curcumin, diosgenin, caprospinol

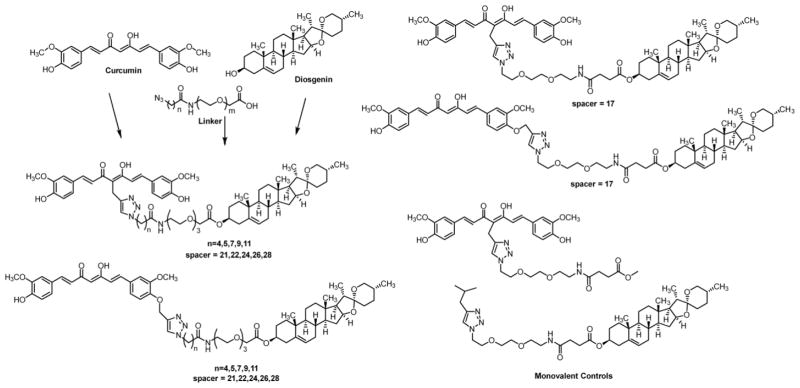

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by an accelerated decline in memory and cognitive function and is also the leading cause of dementia. Currently, an estimated 5.3 million Americans and up to 30 million people worldwide are diagnosed with AD.[1] Unfortunately, current FDA-approved AD treatments only offer symptomatic relief and are unable to delay or cure the disease. Many pathogenic factors have been implicated in the progression of AD including the amyloid-β protein (Aβ), tau protein, neuroinflammation, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and biometal dyshomeostasis.[2–5] Despite significant advances in the understanding of AD pathology, however, the exact etiology is still not fully elucidated. Additionally, the multifactorial nature of AD also makes drug development efforts in providing effective disease-modifying agents a challenging and unmet task.[6, 7]

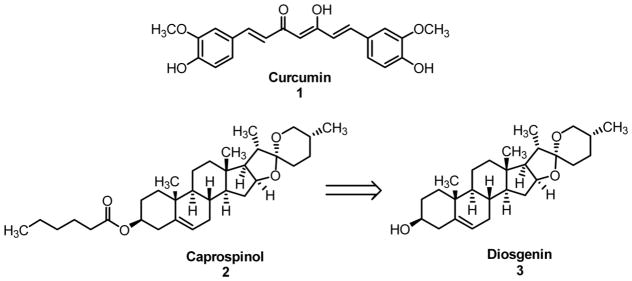

The bivalent strategy approach is defined by its use of two distinct, active molecular species linked together via a spacer in order to target two or more molecular targets typically within close proximity of one another. Recently, we have successfully employed this concept in the creation of two series of bivalent, multifunctional compounds as potential neuroprotectants for AD in our laboratory.[8–10] These compounds included curcumin (1) as the multifunctional inhibitor “warhead” connected to a steroid moiety, acting as a lipid raft/membrane (LR/M) anchor. The key concept here is to localize the beneficial effects of the multifunctional “warhead” to the lipid rafts, where Aβ oligomer (AβO) and ROS production is known to occur, thus improving the efficiency.[11–13] Our previous studies incorporated cholesterol and cholesterylamine as more traditional LR/M anchors. Caprospinol (2), a derivative of the steroid diosgenin (3), is a natural product found in the Gynura japonica plant, and has recently been shown to retain the protective functions of 22R-hydroxycholesterol in Aβ-induced toxicity models.[14] Notably, in contrast to 22R-hydroxycholesterol, 2 was devoid of any steroidogenic activity.[15] Aβ monomer scavenging, decrease in plaque formation, and preservation of respiratory chain function in mitochondria have all been proposed as potential mechanisms of action for 2.[14] Taken together, diosgenin (3) may represent a good candidate as a steroidal moiety in our bivalent compounds against AD pathology, and it might also add additional layers of benefit to the ultimate neuroprotection, given the demonstrated biological activities of 2. Herein, we report the synthesis and biological characterization of a series of bivalent compounds containing curcumin (1) and diosgenin (3) as the multifunctional effector and steroid portion, respectively.

RESULTS

Compound design and synthesis

Our previous studies have established a spacer length of 17 or 21 atoms being optimal for neuroprotective activity, depending upon the steroid moiety.[8, 9] Therefore, we designed bivalent compounds with spacers of 17 and 21 atoms to evaluate whether the same range will be preferred in this series of bivalent compounds, as well. To further evaluate whether increased spacer length will provide improved neuroprotection, we decided to vary the spacer length from 22 to 28 atoms by 2 atom increments. Furthermore, to evaluate whether the preference of attachment position on the curcumin moiety will be the same as previous bivalent compounds, two series of compounds containing different connection sites were designed. In addition, monovalent control compounds with only the spacer attached to only diosgenin or curcumin were designed to further confirm the importance of the bivalent nature (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed series of bivalent compounds varying spacer length and attachment position. Monovalent controls with just curcumin and spacer, or just diosgenin and spacer are also shown.

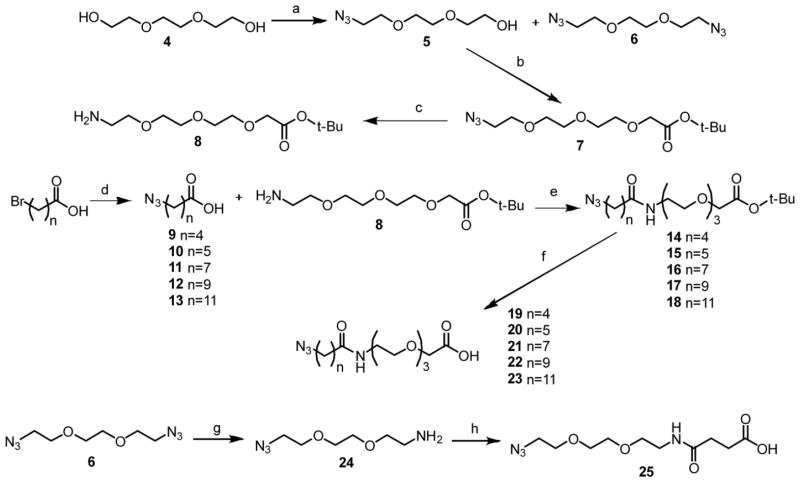

The chemical synthesis of the designed bivalent compounds and control monovalent compounds is outlined in Schemes 1–3. Briefly, 21 to 28 atom spacers were prepared by first reacting triethylene glycol with mesyl chloride followed by sodium azide to afford both the doubly and singly substituted intermediates 5 and 6. Subsequent reaction of 5 with tert-butyl bromoacetate gave intermediate 7. The azide was then reduced by Staudinger reaction to afford 8 in good yield. Azide-substituted carboxylic acids with various aliphatic chain lengths were prepared by reacting the corresponding bromo acid compounds with sodium azide to give intermediates 9–13. The coupling of acids 9–13 with the amine of 8 followed by removal of the tert-butyl group using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) yielded linkers 19–23. The spacer with 17 atoms was synthesized by reducing one azide of the doubly substituted intermediate 6 by Staudinger reaction followed by reaction with succinic anhydride to give 25.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of intermediates 19–23 and 25a

aReagents and conditions: a) i. mesyl chloride, THF, 0 °C; ii. NaN3, TEA, EtOH, reflux; b) tert-butyl bromoacetate, NaH, THF; c) PPh3, THF; d) NaN3, DMF/H2O (4/1); e) EDC, HOBt, TEA, DCM; f) TFA, DCM; g) PPh3, Et2O/EtOAc/5%HCl (1/1/1); h) succinic anhydride, TEA, DCM.

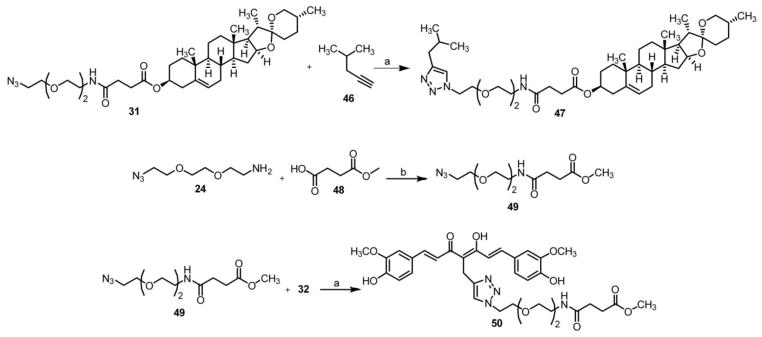

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of control compounds 46 and 48a

aReagents and conditions: a) sodium ascorbate, CuSO4, H2O/THF (1/1); b) EDC, HOBt, TEA, DCM.

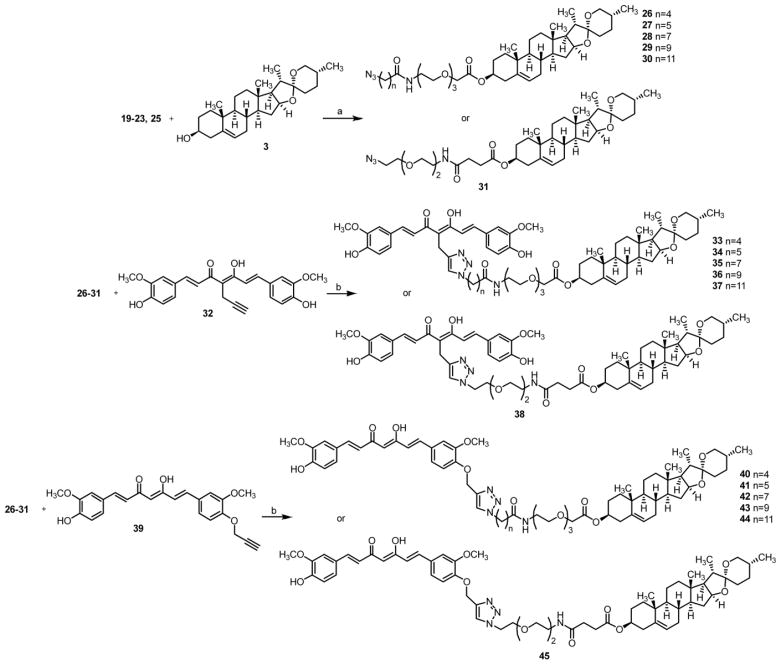

These fully formed linkers were coupled with diosgenin to provide the azido intermediates 26–31. Click reaction of 32 or 39, previously synthesized, with an installed alkyne handle at either the α-carbon in the middle of the diketone (the ‘M’ position) or off the hydroxyl phenolic oxygen of one of the rings (the ‘P’ position) with 26–31 afforded the completed series 33–38 and 40–45, shown in Scheme 2.[8] Control compounds 47 and 50 were created in a similar fashion (Scheme 3) to rule out the effects of the spacer alone on biological activity and to further validate the essential role of the bivalent nature of these compounds.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of target compounds 33–38 and 40–45a

aReagents and conditions: a) DCC, DMAP, DCM; b) Sodium ascorbate, CuSO4, THF/H2O (1/1).

Evaluation of bivalent compounds in MC65 cells

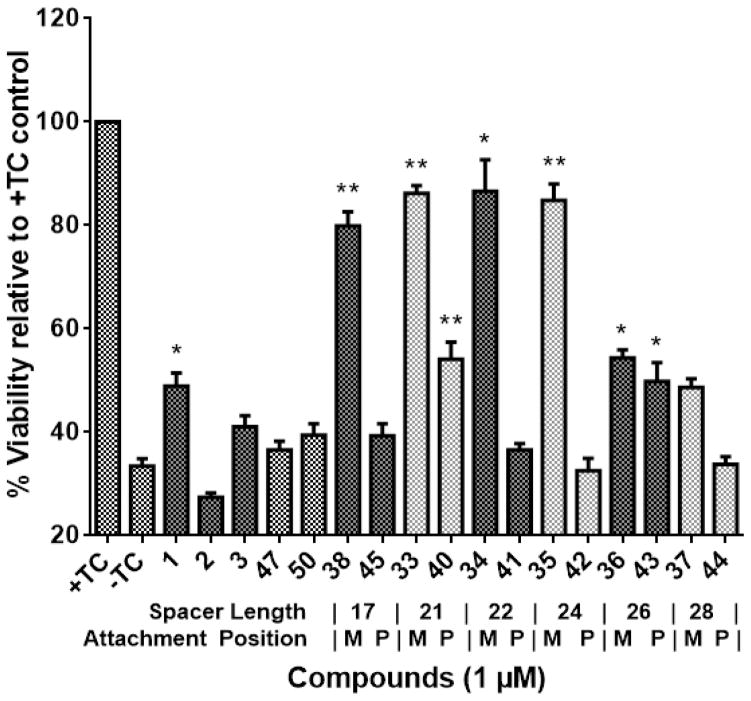

After chemical synthesis, we employed MC65 cells, a cellular AD model that involves multiple factors such as Aβ and oxidative stress in cell death and has been previously utilized in our lab to good effect, to screen these bivalent compounds.[16, 17] For the initial screening, a concentration of 1 μM was chosen to identify active compounds that would potentially display a potency in the submicromolar range, following dose-response assays. As shown in Figure 3, MC65 cell viability dropped almost by 70% upon removal of TC. Curcumin (1) and diosgenin (3) exhibited weak protective abilities, and caprospinol (2) showed no protection at 1 μM in this model. Caprospinol has been shown to be protective in other cellular models of Aβ-induced toxicity, including rat PC12 cells and human SK-N-AS cells, albeit at higher concentrations (30 μM and 10 μM, respectively).[15, 18] However, it has not been previously characterized in MC65 cells, and may not exhibit the same activity or potency in this model due to the difference in Aβ species involved. Notably, for all bivalent compounds, the ‘M’ position attachment exhibited better protection than the ‘P’ position attachment, and this preference is in agreement with our previously reported results, highlighting the importance of the attachment position and overall orientation of the bivalent compounds.[8, 9] Compounds 38, 33, 34, and 35 with spacer lengths of 17, 21, 22, and 24 atoms, respectively, all exhibited strong neuroprotection, rescuing viability to 80% or greater. After increasing the spacer length to 26 atoms or more, however, protective function dropped by about 25%, suggesting that the curcumin and steroid structures may not be able to orientate in a proper fashion with too long of a linker. Furthermore, control compounds 47 and 50, containing linker connected to only diosgenin or only curcumin, respectively, showed no significant protection. This confirms that the inclusion of all three parts of the bivalent structure is essential for biological activity and provides more evidence to support the bivalent design strategy. Further dose-response studies of the ‘M’ attachment series, as shown in Table 1, established EC50s in the nanomolar range with compound 38, having a spacer length of 17 atoms, exhibiting the highest potency with an EC50 of 111.7 ± 9.0 nM. Not surprisingly, these linkers were also of the optimal lengths revealed from our previous reports.[8, 9] Taken together, these results may suggest that upon anchorage to the appropriate membrane site, an ideal spacer length range is required to properly orient the “warhead” moiety to achieve optimal interactions and ultimately, optimal neuroprotective activity. This also suggests that the anchor moiety can be modified to improve the overall physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of the bivalent compounds. Based on these results, compounds 33 and 38 were selected for further biological characterization.

Figure 3.

Protective abilities of bivalent compounds in MC65 cells. MC65 cells were treated with indicated compounds for 72 h under −TC conditions. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay and is represented as percent viability compared to the +TC control. Error bars represent SEM. (* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to −TC control.)

Table 1.

Potency of bivalent compounds with the ‘M’ attachment position. MC65 cells were treated with bivalent compounds over a range of concentrations for 72 h and viability was assessed by MTT assay. The resulting EC50 values are given as concentration ± SEM.

| ‘M’ Series | EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|

| 33 | 231.7 ± 15.1 |

| 34 | 380.8 ± 34.1 |

| 35 | 1036.9 ± 14.3 |

| 36 | 309.0 ± 1.5 |

| 37 | 4616.0 ± 658.9 |

| 38 | 111.7 ± 9.0 |

Compounds 33 and 38 reduce ROS production and do not chelate biometals

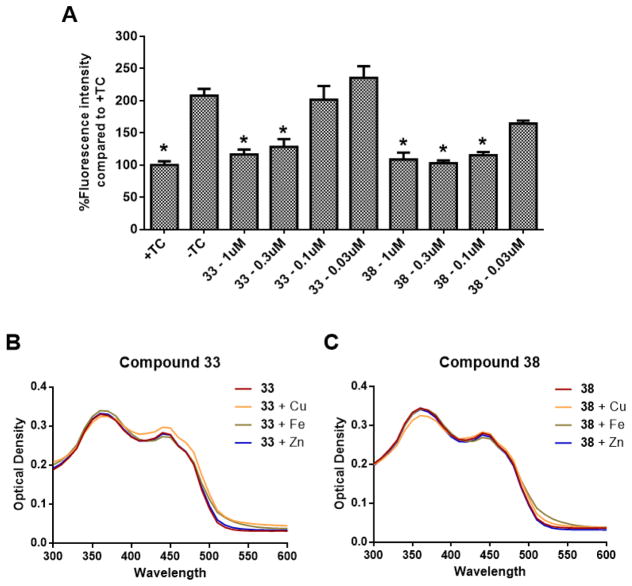

Oxidative stress has been well-documented in the progression of AD and has also been implicated as a contributor to the toxicity of MC65 cells upon the accumulation of intracellular Aβ.[16, 19–21] Additionally, dyshomeostasis of metal ions is known to play a role in the development of AD pathologies, and it has been suggested that metal ions are involved in the assembly and neurotoxicity of Aβ, and may contribute to oxidative stress, as well.[22–24] From our previous studies, we observed that our bivalent compounds retain the antioxidative effects of curcumin, and these effects might be due to interaction with the mitochondria.[10] Furthermore, our previous results also suggested the involvement of all three parts of the bivalent compounds, rather than just the curcumin moiety, are in involved in chelating biometals. Therefore, to examine whether the replacement of the anchor moiety with diosgenin will affect such properties, compounds 33 and 38 were evaluated for their antioxidative function in MC65 cells and biometal binding ability. As shown in Figure 4A, removal of TC led to a significant increase in intracellular oxidative stress compared to the +TC control, as measured by the fluorescence intensity of reduced 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH). This increase in ROS levels was completely ameliorated by both 33 and 38 at concentrations as low as 0.3 μM and 0.1 μM, respectively, which are consistent with the EC50 values from the neuroprotection assays. Because the potencies in rescuing cell viability correlate closely with those for ROS reduction, this may suggest that antioxidative capability could be a major mechanism of protection for these compounds. Interestingly, neither 33 nor 38 were shown to complex with Cu2+, Fe2+, and Zn2+, as shown in Figures 4B and 4C, unlike curcumin and our previous bivalent compounds containing cholesterol or cholesterylamine as anchor moieties.[8, 9] This further confirms the notion that participation of the linker and the membrane anchor moiety is essential in metal binding interactions. The change in metal binding capacity of 33 and 38 could be due to the interaction of the linker or diosgenin (3) with the β-diketone moiety of curcumin (1), thus affecting its keto-enol equilibrium, which plays a role in metal binding.[25] Since both the linker composition and the anchor moiety were changed in this series of bivalent compounds, further studies are warranted to dissect the influence of the linker and anchor on metal binding interactions. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that biometals may be playing a role in the production of ROS. Since our bivalent compounds 33 and 38 are not directly complexing with these metals, their antioxidative properties could be through a different mechanism, such as interaction with mitochondria. This is somewhat consistent with our recent findings using another bivalent compound with cholesterylamine that showed that the anchor moiety and spacer length can affect the cellular localization of these compounds, thus leading to different mechanisms of action with regard to interacting with mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum (unpublished data).[10] Again, this suggests that the bivalent strategy not only provides compounds with multifunctionality similar to the parent molecules, but also with novel mechanisms of action, and this functionality can be fine-tuned by modification of one of the various structural components of these compounds, as well.

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 33 and 38 on ROS production and biometal binding. (A) MC65 cells were treated with 33 or 38 at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. Cells then were incubated with DCFH-DA for 1 h. The amount of ROS is represented as percent fluorescence intensity compared to the +TC control. Error bars represent SEM. (* p < 0.05 compared to −TC control.) (B, C) Compounds 33 and 38 were incubated with CuSO4, FeCl2, or ZnCl2 at room temperature for 10 min. UV-vis spectrum was recorded from 300 nm to 600 nm.

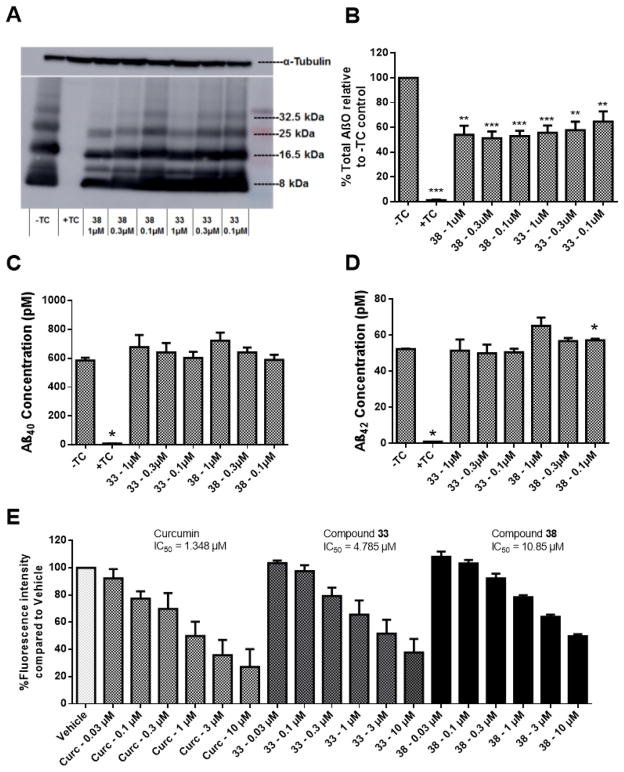

Compounds 33 and 38 have no impact on Aβ production, but can bind to Aβ and prevent oligomerization

The overproduction of Aβ and the formation of AβOs is central to the development and progression of AD.[2, 26, 27] Because of this, one of the potential functions of the designed ligands is the prevention of Aβ oligomerization. To evaluate the effects of compounds 33 and 38 on the formation of AβOs, MC65 cells were examined by western blot upon treatment with 33 and 38. As expected, inclusion of TC to the cell medium completely abolished the expression of Aβ, and removal of TC significantly increased the production of AβOs (Figure 5A). Notably, both 33 and 38 dose-dependently suppressed the levels of AβOs at similar concentrations to those that can reduce ROS (Figure 5B). This clearly suggests a correlation between AβO formation and ROS production in this cellular model, consistent with previous reports in the literature.[16, 17] To rule out the possibility that the decrease of AβOs is not simply due to inhibition of Aβ production, total Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were measured by ELISA. Consistent with the western blot studies, the presence of TC completely blocked Aβ production and its removal led to a sharp increase. Treatment with 33 or 38 had no significant impact on total Aβ40 or Aβ42 concentrations, thus supporting their inhibitory effects on the process of Aβ oligomerization (Figure 5C and 5D). To further confirm the direct binding interaction of these compounds with Aβ, 33 and 38 were tested in the aggregation of synthetic Aβ42 by ThT assay. Curcumin was also tested as a positive control. As shown in Figure 5E, both 33 and 38 dose-dependently inhibited Aβ aggregation with IC50s of 4.79 μM and 10.85 μM, respectively. Curcumin is slightly more potent than 33 and 38 under the same assay conditions. However, curcumin only moderately protects MC65 cells, suggesting that the direct inhibition of Aβ oligomerization may be partially contributing to the observed protective activities in protecting MC65 cells along with other factors. Our recent studies also demonstrated that our bivalent compounds not only localize into the cell membrane, but also to intracellular organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, and exert their neuroprotection via a multi-target mechanism.[10] In addition, our results demonstrated that the ‘P’ attachment compounds can also bind to Aβ42 (data not shown), thus further suggesting that the observed protective activities originate from multiple factors. Taken together, the results echo and reassure our previous conclusion that the bivalent nature of these compounds is essential for their biological outcomes, and this strategy not only provides multifunctionality but also compounds with novel mechanisms of action.

Figure 5.

Compounds 33 and 38 bind Aβ and reduce AβO formation, but have no effect on Aβ production. (A) Representative western blot. Cells were treated were lysed, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to a PVDF membrane, blots were probed with the 6E10 antibody. (B) Quantification of total Aβ oligomers from western blotting. Error bars represent SEM. (n=6; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to −TC control.) (C, D) Cells were treated with 33 or 38 at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. The conditioned media was collected and the Aβ40 (C) and Aβ42 (D) concentrations were measured by ELISA assay. Error bars represent SEM. (* p < 0.05 compared to −TC control.) (E) Curcumin (Curc) and compounds 33 and 38 were incubated at the indicated concentrations with Aβ42 for 48 h. ThT was then added, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using wavelengths of 446 nm (excitation) and 490 nm (emission). Error bars represent SEM.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have designed and synthesized a new series of bivalent compounds containing curcumin and diosgenin to further explore our design approach in developing multifunctional compounds as potential AD treatments. Biological characterization of these compounds for protective activity in MC65 cells confirmed a preference for the ‘M’ position over the ‘P’ position, consistent with our previous series. Extension of spacer lengths to more than 24 atoms led to a loss of neuroprotective activity. This highlights the importance of these structural features for biological activity and stresses their need for consideration when designing new compounds. Bivalent compounds 33 and 38 demonstrated the best protective profiles in MC65 cells with spacer lengths of 21 and 17 atoms, respectively. Further biological studies of these compounds revealed antioxidative and anti-oligomerization ability, which may be responsible for their protective activity in MC65 cells. Compared with our previous bivalent compounds containing cholesterol and cholesteylamime as the anchor moieties, these compounds exhibited similar potencies in protecting MC65 cells from TC removal-induced toxicity.[8, 9] Notably, they also share the same optimal spacer range with our previously reported bivalent compounds. This may suggest that diosgenin could serve as an optimal anchor moiety, given its non-steroidogenic activity along with other reported beneficial effects.[14, 15] Furthermore, in this series of bivalent compounds, spacers with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) structure were employed, which are different from our previously published bivalent compounds. One of the reasons for this incorporation was to modify solubility properties and to impart flexibility for the longer spacer lengths.

Interestingly, these compounds were unable to bind biometals, in contrast to the parent compound curcumin. This could be due to the linker composition or inclusion of the diosgenin steroid and suggests the impact these structures might have on function, given the fact that the spacer contains a PEG component with multiple oxygen atoms, as well as an NH moiety. The change from more traditional cholesterol/cholesterylamine to diosgenin may also influence the overall conformation of the bivalent structures, thus changing the metal chelating properties. To elucidate the role of the spacer’s participation in the overall pharmacology, compounds containing identical spacers with differing steroid anchors are necessary, and the synthesis and biological characterization of such are currently being undertaken in our laboratory. Despite this lack of biometal chelation, these compounds retain their protective activity signifying that reduction in ROS and AβO formation may be more pertinent in this cell model, and further supporting the use of multifunctional, bivalent compounds as a viable strategy in developing effective AD treatments. Based on these results, development and optimization of 33 or 38 is warranted and may lead to more potent neuroprotective agents.

METHODS

MC65 Cell Culture and Reagents

MC65 cells (kindly provided by Dr. George M. Martin at the University of Washington, Seattle) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) (Invitrogen), 1 μg/mL Tetracycline (TC) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.2 mg/mL G418 (Invitrogen). All assays were carried out in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a fully humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cell controls were prepared in Opti-MEM with or without TC (+TC or −TC).

MC65 Viability

MC65 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 96-well plates (4×104 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C under +TC or −TC conditions for 72 h. Then, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added and the cells were incubated for another 4 h. Cell medium was then removed, and the remaining formazan crystals produced by the cellular reduction of MTT were dissolved in DMSO. Absorbance at 570 nm was immediately recorded using a FlexStation 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). Values are expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in the +TC controls.

ROS Production

MC65 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 6-well plates (2×106 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C under +TC or −TC conditions for 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, then suspended in PBS and incubated with DCFH-DA (25 μM) in dark for 1 h. Fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry using a Millipore Guava easyCyte flow cytometer. Values are expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in −TC controls.

Biometal Chelation

Compounds (50 μM) and CuSO4, FeCl2, or ZnCl2 (50 μM) in deionized water were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and then UV absorption was recorded from 200 nm to 600 nm on a Flexstation 3 plate reader.

Aβ Western blot

MC65 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 6-well plates (2×106 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C under +TC or −TC conditions for 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, and then lysed by sonication in a Tricine buffer solution. Protein samples were collected from the supernatant after centrifugation at 12,000×g for 5 min, and then quantified using the Bradford method. Equal amounts of protein (20.0 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a Tris-Tricine gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked with a 5% milk in TBS-Tween 20 (0.1% Tween) (TBST) solution at room temperature for 1 h, and then probed with the 6E10 antibody (Signet, Dedham, MA) overnight at 4 °C. Blots were washed twice in TBST for 15 min, and then incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. After washing twice in TBST for 15 min, the proteins were visualized by a Western Blot Chemiluminescence Reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). Blots were also probed with antibodies against α-tubulin to ensure equal loading of proteins.

Aβ ELISA

MC65 cells were cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 96-well plates (4×104 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C under +TC or −TC conditions for 48 h. The conditioned media was then added to ELISA plates precoated with BNT77 antibody (Wako, Richmond, VA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were then washed and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were added, BA27 for Aβ40 or BC05 for Aβ42, and plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After washing again, TMB was added to initiate the HRP reaction, and plates were incubated in dark at room temperature for 30 min. Stop solution was then added to terminate the reaction. Absorbance at 450 nm was immediately recorded using a FlexStation 3 plate reader. Values are expressed in pM and were calculated using calibration curves generated with Aβ standard proteins.

Thioflavin T Aβ Aggregation

A thioflavin T (ThT)-binding assay, used to measure Aβ aggregation, was conducted following published methods.[28] Aβ42 was obtained from American Peptide, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Compound solutions were prepared in DMSO (0.01 μM to 100 μM) and 1 μL was added to corresponding wells in a 96-well plate. Each concentration was prepared as independent triplicates, and a solvent control was included. To each well, 9 μL of 25 μM Aβ42 in PBS (pH 7.4) was added, and plates were then incubated in dark at room temperature for 48 h. Next, 200 μL of a 5 μM ThT in 50 mM glycine solution (pH 8.0) was added to each well. Fluorescence was immediately recorded using a FlexStation 3 plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 446 nm and an emission wavelength of 490 nm. Fluorescence readings of each concentration without ThT were also measured and subtracted to remove background signals.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Bivalent compounds are composed of the natural product curcumin 1 and the natural steroid diosgenin 3.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. George M. Martin at the University of Washington, Seattle for kindly providing the MC65 cells. The work was supported in part by the NIA of the NIH under award number R01AG041161 (S.Z.) and the VCU Lowenthal Award (J.C.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AβO

amyloid-β oligomer

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- DCC

N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DCFH

2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

- DCFH-DA

2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- LR

lipid raft

- MTT

(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide)

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TBST

tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20

- TC

tetracycline

- TEA

triethylamine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- ThT

thioflavin T

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: implications for therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:479–497. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T, Vitorica J, Ransohoff RM, Herrup K, Frautschy SA, Finsen B, Brown GC, Verkhratsky A, Yamanaka K, Koistinaho J, Latz E, Halle A, Petzold GC, Town T, Morgan D, Shinohara ML, Perry VH, Holmes C, Bazan NG, Brooks DJ, Hunot S, Joseph B, Deigendesch N, Garaschuk O, Boddeke E, Dinarello CA, Breitner JC, Cole GM, Golenbock DT, Kummer MP. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu X, Su B, Wang X, Smith MA, Perry G. Causes of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2202–2210. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush AI. Drug development based on the metals hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:223–240. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Why pleiotropic interventions are needed for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41:392–409. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carreiras MC, Mendes E, Perry MJ, Francisco AP, Marco-Contelles J. The multifactorial nature of Alzheimer’s disease for developing potential therapeutics. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:1745–1770. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenhart JA, Ling X, Gandhi R, Guo TL, Gerk PM, Brunzell DH, Zhang S. “Clicked” bivalent ligands containing curcumin and cholesterol as multifunctional abeta oligomerization inhibitors: design, synthesis, and biological characterization. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6198–6209. doi: 10.1021/jm100601q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K, Gandhi R, Chen J, Zhang S. Bivalent ligands targeting multiple pathological factors involved in Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:942–946. doi: 10.1021/ml300229y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, Chojnacki JE, Wade EE, Saathoff JM, Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Zhang S. Bivalent Compound 17MN Exerts Neuroprotection through Interaction at Multiple Sites in a Cellular Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:1021–1033. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordy JM, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. The involvement of lipid rafts in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:111–122. doi: 10.1080/09687860500496417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen RB, Nunomura A, Lee HG, Casadesus G, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Signal transduction cascades associated with oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:143–152. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SI, Yi JS, Ko YG. Amyloid beta oligomerization is induced by brain lipid rafts. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:878–889. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadopoulos V, Lecanu L. Caprospinol: discovery of a steroid drug candidate to treat Alzheimer’s disease based on 22R-hydroxycholesterol structure and properties. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecanu L, Yao W, Teper GL, Yao ZX, Greeson J, Papadopoulos V. Identification of naturally occurring spirostenols preventing beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Steroids. 2004;69:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sopher BL, Fukuchi K, Kavanagh TJ, Furlong CE, Martin GM. Neurodegenerative mechanisms in Alzheimer disease. A role for oxidative damage in amyloid beta protein precursor-mediated cell death. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1996;29:153–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02814999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maezawa I, Hong HS, Wu HC, Battina SK, Rana S, Iwamoto T, Radke GA, Pettersson E, Martin GM, Hua DH, Jin LW. A novel tricyclic pyrone compound ameliorates cell death associated with intracellular amyloid-beta oligomeric complexes. J Neurochem. 2006;98:57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tillement L, Lecanu L, Yao W, Greeson J, Papadopoulos V. The spirostenol (22R, 25R)-20alpha-spirost-5-en-3beta-yl hexanoate blocks mitochondrial uptake of Abeta in neuronal cells and prevents Abeta-induced impairment of mitochondrial function. Steroids. 2006;71:725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuyama H, Ogawa M, Yamauchi H, Yamaguchi S, Kimura J, Yonekura Y, Konishi J. Altered cerebral energy metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease: a PET study. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee HG, Zhu X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophy Acta. 2014;1842:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manczak M, Anekonda TS, Henson E, Park BS, Quinn J, Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenough MA, Camakaris J, Bush AI. Metal dyshomeostasis and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:540–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu WP, Chang GL, Chen SJ, Kuo YM. Kinetic analysis of beta-amyloid peptide aggregation induced by metal ions based on surface plasmon resonance biosensing. J Neurosci Meth. 2006;154:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baum L, Ng A. Curcumin interaction with copper and iron suggests one possible mechanism of action in Alzheimer’s disease animal models. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:367–377. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6403. discussion 443–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chojnacki JE, Liu K, Yan X, Toldo S, Selden T, Estrada M, Rodriguez-Franco MI, Halquist MS, Ye D, Zhang S. Discovery of 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-oxo-pentanoic acid [2-(5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethyl]-amide as a neuroprotectant for Alzheimer’s disease by hybridization of curcumin and melatonin. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:690–699. doi: 10.1021/cn500081s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.