The term “CRISPR” has gained a lot of attention recently as a result of a debate among scientists about the possibility of genetically modifying the human germ line and the ethical implications of doing so. However, CRISPR is not just a method to edit the genomes of embryonic cells, as the public discussion might have implied; it is a powerful, efficient, and reliable tool for editing genes in any organism, and it has garnered significant attention and use among biologists for a variety of purposes. Thus, in addition to the discussion about human germ line editing, CRISPR raises or revives many other ethical issues, not all of which concern only humans, but also other species and the environment.

“… CRISPR raises or revives many other ethical issues, not all of which concern only humans, but also other species and the environment”

CRISPRs are short DNA sequences with unique spacer sequences that, along with CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins, constitute an adaptive immune system in many bacteria and archaea against invading bacteriophages 1. By using short RNA molecules as a template, Cas makes highly sequence-specific cuts in DNA molecules that can be exploited to insert genes or to precisely modify the nucleotide sequence at the cut site. CRISPRs were first identified in the 1980s, but it is only during the past few years that scientists realized their potential to edit the genomes of any organism, from microorganisms to plants to human cells and, most controversially, human embryos. The CRISPR/Cas system is not a breakthrough technology in the sense that it enables genome editing; biologists have been using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) to edit genomes for some time. However, those technologies are expensive, technically challenging, and time-consuming, as they require protein engineering to target specific DNA sequences. CRISPR/Cas, in contrast, recognizes its target sequence via guide RNA molecules that can be cheaply and easily synthesized. A standard molecular biology laboratory can now edit genes or whole genomes of many organisms, as CRISPR/Cas does not require sophisticated knowledge or expensive equipment.

This has rekindled the ethical debate about modifying the human germ line. Notwithstanding the talk about “designer babies,” CRISPR/Cas offers new possibilities to render humans immune to a range of diseases, or to repair fatal gene defects in a human embryo. Prominent researchers have therefore called for a voluntary moratorium on germ line genome modification in humans until scientists and ethicists have jointly analyzed the implications of doing so 2. The debate boils down to two sides in a “go/no-go” standoff. One group insists that research on human germ line editing should advance in order to reap the scientific and clinical benefits, while the other camp argues that editing the human germ line is too unsafe, or crosses an inviolable ethical line 3.

“… there is a danger that CRISPR’s affordability and efficiency could run roughshod over long-standing and valid concerns about the generation and release of […] GMOs.”

However, rather than the use or not of CRISPR to edit human germ cells and embryos, there are more immediate ethical concerns that need to be addressed. CRISPR is already being used to modify insects, animals, plants, and microorganisms and to produce human therapeutics 4. Since such work has been going on for years—or even decades—the CRISPR technology may not appear to create new ethical problems in these contexts. However, there is a danger that CRISPR’s affordability and efficiency could run roughshod over long-standing and valid concerns about the generation and release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The recent characterization of a new type 2 CRISPR system from Francisella novicida demonstrates that the toolbox of genome editing technologies is ever-expanding 5. Consequently, there is an urgent need for effective, global regulations that govern the testing and environmental release of GMOs.

Current national and international regulations provide inadequate guidance and oversight for these applications. As such, they do not foster public trust in the safety of CRISPR-edited organisms or the regulatory agencies charged with monitoring them. The concern is that public misunderstanding and mistrust of GMOs will hinder scientific progress and valid uses of CRISPR. Thinking through—and getting right—the regulations and research ethics for these applications of CRISPR might also help to create an ethical framework for human germ line editing.

In the USA, the regulation of genetically modified animals and insects is done by a number of regulatory agencies that comprise the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology, which was created in 1986 to facilitate inter-agency regulation of biotechnology. Its scope and regulatory approach has not been revisited since 1992 6, but individual agencies within the Coordinated Framework—the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—have issued their own guidelines on particular applications.

“The concern is that public misunderstanding and mistrust of GMOs will hinder scientific progress and valid uses of CRISPR”

FDA guidance issued in 2009 states that the genetic modification of an animal, regardless of the animal’s use, meets the criteria for veterinary medicine and is thus regulated by the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Genetically modified animals used to study human diseases and drug testing are regulated by the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. The Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAP) and the USDA are brought in if the effects of a proposed modification will affect processes or products that they oversee—for example, food safety or pest control, respectively. There are potential roles for the EPA, the Department of the Interior and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, on a case-by-case basis.

The EU has a more centralized regulatory scheme in which the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) conducts risk assessments, while final approval of a genetically modified animal or plant falls to the European Commission (EC). Analogous to the USA, human therapeutic applications are regulated and approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Other countries with intense biomedical research programs likewise have their own regulatory and oversight schemes. Internationally, there is no unified guidance for the modification of non-human organisms other than the Biological and Chemical Weapons Convention, which seeks to prevent research into and development of biological weapons.

Some applications of CRISPR in animals improve current standard practices in the biomedical sciences. For example, some research projects require animal lines that are specifically bred for certain mutations. Using CRISPR to generate these lines produces less genetic variability than standard breeding techniques and helps researchers to introduce mutations that more accurately represent the human genetic defects they study 7. Though there are standing ethical issues implicated by this practice, such as animal welfare, using CRISPR for this purpose does not challenge existing regulations of laboratory animals.

Other applications in animals, however, pose novel ethical concerns. In particular, CRISPR could be used to replace expensive TALENs, ZFNs, and other methods of genetic modification to improve food for human consumption. For example, CRISPR could be used to increase the muscle mass of animals, render farmed animals less susceptible to disease, enhance nutritional content, or create hornless cattle that are easier to handle 4. Research groups and private biotech companies are currently assessing whether such genome edits are feasible and safe. So far, no genetically modified animal has ever been approved for human consumption; the approval of genetically modified salmon for human consumption has been pending at the FDA for years. But it is not clear what criteria the FDA—or any other agency involved—uses for assessing the safety of genetically edited animals for human consumption. These regulatory processes must be more transparent and accountable.

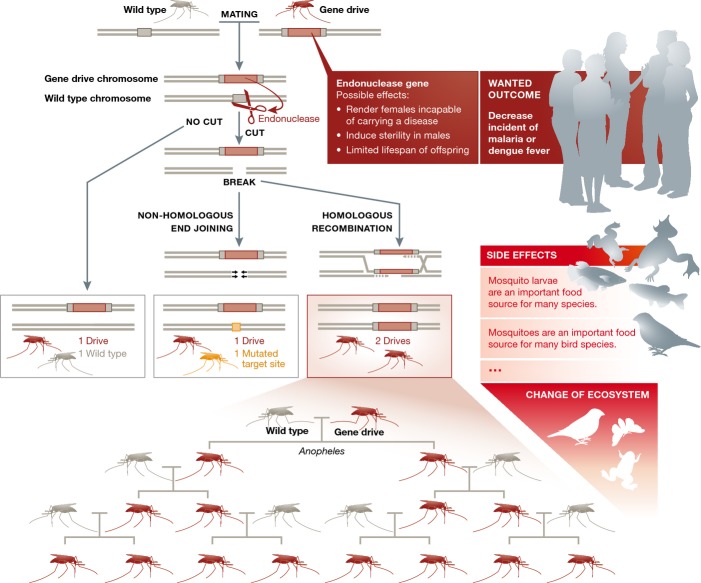

There is another, potentially much more dangerous and controversial, application of CRISPR, namely to potentially eradicate disease by eradicating disease vectors and invasive species 8. This involves research with the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which transmits dengue fever, and certain subspecies of the Anopheles mosquito that carry the Plasmodium parasite. Researchers at academic centers and private biotech firms are exploring so-called gene drives to block disease transmission by editing the female mosquito so as to render it incapable of carrying the disease. Others aim to induce sterility in male mosquitos to prevent reproduction, or limit the lifespan of their offspring. Such methods could effectively destroy an entire species and could have significant environmental consequences.

Gene drive is a powerful tool that makes it more likely that the edited trait will be passed on to offspring through sexual reproduction. When genetically modified organisms are introduced into the environment and mate with wild-type organisms, their offspring generally have a 50% chance of inheriting the modified genes (Fig 1). The introduction of a few edited mosquitos or animals is therefore unlikely to have much of an effect. However, gene drive actively copies a mutation made by CRISPR on one chromosome to its partner chromosome and thereby ensures that all offspring and subsequent generations will inherit the edited genome. Over generations, this would lead to a noticeable effect: for example, in lowering transmission rates of dengue fever or malaria. The use of gene drives, though, also poses a much larger risk to the environment, as they have the potential to decimate an entire species, eliminate a food source for other species, or promote the proliferation of invasive pests.

Figure 1. Gene drives can be used to alter population-wide traits.

A gene drive is preferentially inherited by all offspring and would quickly spread itself in the target population. The endonuclease cuts the homologous wild-type chromosome; repairing the break using homologous recombination therefore copies the gene drive onto the wild-type chromosome. Gene-drive technology could be used to eradicate diseases, such as malaria or dengue fever, by targeting wild populations of disease-transmitting mosquitoes but could have unanticipated secondary effects on other species. Figure adapted from 9.

“The use of gene drives, though, also poses a much larger risk to the environment, as they have the potential to decimate an entire species …”

Scientists have already called for strict biosafety measures and public review when it comes to introducing edited animals and insects into the environment 9. Yet, many questions remain unanswered: Can off-target effects of CRISPR—unanticipated mutations leading to undesirable phenotypes—be controlled? What are the effects on animals or humans who eat genetically edited insects or animals? Will wiping out an entire species—albeit invasive, or disease-bearing, such as mosquitos or ticks—upset the ecological balance? Will edited organisms be able to survive in natural environments, and if so, for how long? Addressing these questions requires far more regulatory oversight than currently exists anywhere in the world.

Editing the genomes of crops and trees is not new, and debates over the pros and cons of genetically modified (GM) plants have gone on for decades in the USA and Europe, and, more recently, globally. Agriculturally important plants have been genetically manipulated to make these less susceptible to disease and pests, more productive, and more resilient to changing climates. What makes CRISPR different from other methods of agricultural genetic engineering is that it no longer requires the insertion of foreign DNA into the plant genome using a virus, bacterial plasmid, or other vector system. Various commentators have therefore called for changes in the regulation of GM plants because CRISPR- or TALEN-edited organisms would no longer classify as transgenic organisms in sensu strictu.

In the USA, the Coordinated Framework under the purview of the USDA, the FDA, and the EPA provides guidance on agricultural applications of genome editing, but their regulations only cover “plant pests”—animals, bacteria, fungi, or parasitic plants that can directly or indirectly damage crop plants or parts thereof. This stipulation enters the regulatory process when parts of pest DNA are inserted into a host organism, or when certain viral vectors are used. The plant pest regulations also govern edits to insects that are detrimental to crops, plants, and trees, whereas applications of CRISPR that do not use pests or pest parts to induce genetic edits fall outside current regulations. Since the regulations frame the insertion of DNA as genetic material from a “donor organism,” it is also unclear whether the regulations cover copies of pest DNA that are synthesized in the laboratory.

“Without clear safety and testing guidelines, and public engagement and discussion, the public’s trust in the safety of GE insects and animals will follow the same path as GM food”

The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), an arm of the USDA, reviews applications for research on GM crops. APHIS has indicated that products resulting from CRISPR/Cas that only delete a gene, in most cases, would not be regulated because no new genetic material is integrated into the recipient genome. Substitutions and insertions of genes would be reviewed on a case-by-case basis to determine whether the inserted trait counts as a pest. In recent years, APHIS has seen an increase in requests for non-regulation status by academic centers and biotech companies asking them to affirm that their products do not fall under current regulations, and so do not warrant review for safety and efficacy by federal agencies. The current trend toward deregulation will promote research into a variety of applications of CRISPR, but the wide implementation of those edits without enforceable oversight could be detrimental to ecosystems, biodiversity, and human health.

In contrast to the USA, the European Union (EU) has much stricter regulatory regime for genetically modified crops in agriculture. It requires an extensive risk assessment by EFSA before the EC decides to grant or withhold approval for use in the EU. EU regulation currently considers all genetically modified crops or animals as transgenic—whether this includes the insertion of foreign DNA or direct genome editing—and therefore subject to regulation and risk assessment. However, there is ongoing debate arguing that CRISPR- or TALEN-edited plants without any foreign DNA should not be subjected to the same regulatory regime and risk assessment as transgenics. Since the EU is the largest market for agricultural products in the world, other countries are now waiting to see whether the EC will change its definition of transgenic and its regulations before they move on with marketing edited crop plants.

The US Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology was created to facilitate a unified approach to biotech regulation, but it is no longer adequate in the age of CRISPR 6. Even the EU’s stricter regulatory regime is not suitable to address all possible risks—in particular with gene drive—as it is designed to regulate transgenic organisms. Moreover, given that CRISPR is cheap, easy to use, and does not require sophisticated equipment or expert knowhow, it has become a popular technology worldwide, which will eventually require international standards for testing genetically edited organisms, releasing them into the environment, and assigning liability for damage. Regulations should set clear requirements for testing the safety and efficacy of edited organisms in carefully controlled environments or contained settings that simulate their natural environments 8. Gene drives in particular should be approved only if the safety and efficacy of desired edits have been rigorously tested. Finally, edited organisms should only be released in typical environments, whether on a farm or in a wild habitat, after public consultation and appropriate consent of potentially affected populations.

Regulations should also require the development of methods to halt the effects of edited insects or animals should they prove harmful to other organisms, the environment, or humans. Such reversal, immunization, and suppression drives would neutralize the effects of already-released gene drives by introducing new genes into the population to counter unwanted effects from previous generations 9. However, these safety mechanisms are limited by the same facts that limit all gene drives. As the species must reproduce through multiple generations for the desired trait to proliferate, the negative environmental impacts caused by the original gene-drive population cannot be immediately halted by a counter gene drive. Furthermore, natural mutations cannot be prevented in the wild and might eliminate an engineered trait—whether the original gene-drive edit or the counter edit—anytime after introduction 9.

One approach to address this problem would be so-called terminator genes or self-limiting genes that limit the lifespan of edited organisms or make engineered organisms more fragile or easy to kill. In addition, edited insects and animals should also be tagged to be able to assign responsibility and liability for damages. It would also enable researchers to better track the flow of gene edits through a population of insects or animals.

These are not merely theoretical scenarios. A private biotech company is developing GE mosquitos in Florida with the aim of lowering the incidence of dengue fever by suppressing the population of A. aegypti mosquitos. To date, the FDA has not approved the trial; environmental review and the public comment period are pending. Some Florida residents strongly oppose the release of the GE mosquitos, citing human safety and environmental concerns. They do have a point, as GE organisms will not always move and behave in predictable ways; GE mosquitos, for instance, even if released on an isolated island, might end up many miles away and have unanticipated effects on the environment such as crossbreeding with related species. Without clear safety and testing guidelines, and public engagement and discussion, the public’s trust in the safety of GE insects and animals will follow the same path as GM food.

“It is not unreasonable to think that, in the wrong hands, CRISPR could be used to make dangerous pathogens even more potent”

CRISPR is now being applied in many academic and industry laboratories around the globe. International treaties and policies are therefore required to govern the release of GE organisms into the environment. The WHO’s “Guidance framework for testing of genetically modified mosquitos” for instance suggests updating the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety 10. Article 17 of the Protocol obligates parties to notify an International Biosafety Clearinghouse and affected nations of releases that may lead to movements of modified organisms with adverse affects on biological diversity or human health. However, the document does not specify who will enforce the treaty, what prior testing ought to have been conducted, what the limits on organism viability should be, what methods should be used to assess effects, or how to estimate damages or mitigate harms. The treaty’s effectiveness is further limited by voluntary participation. Some significant players in the field of genetic engineering, including the USA and South Korea, are not parties to the Cartagena Protocol.

CRISPR is also an enormously powerful tool for synthetic biology to generate microorganisms for a broad range of applications, from the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, or chemicals to the remediation of pollution or disease diagnostics and treatment. Gene editing allows synthetic biologists to design and edit whole genomes of bacteria and viruses with new properties, but it raises the same concerns about accidental or deliberate release of GE microorganisms into the environment.

In the USA, the regulation of genetically modified microorganisms is under the purview of various agencies: the FDA, the EPA, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), but they lack sufficient control and monitoring capacity. The NIH has guidelines for the use of recombinant DNA technology, of which CRISPR is one, that require notification and containment procedures based on the organism’s pathogenicity, virulence, communicability, and environmental stability. However, research not funded by the NIH is not subject to these guidelines. The EPA requires notification of new chemical production, which covers some commercial applications of synthetic biology, but the agency relies on voluntary reports and does not perform proactive audits and does not monitor smaller scale operations. The FDA requires that drugs and biologics be proven safe and effective before entering the market, which covers synthetic biology-based human therapeutics, but it does not require specific containment methods to prevent accidental release or design controls such as terminator genes. Only the NIH’s guidance was designed specifically to address genetically modified microorganisms, yet it is also the agency with the least regulatory authority. As CRISPR becomes the primary method of genetic engineering, it would behoove these agencies to require that researchers demonstrate sufficient control mechanisms as a condition of using the CRISPR editing system.

There is yet another aspect of the genetic editing of microorganisms to consider, as CRISPR could also be used to synthesize and manipulate pathogens, including smallpox, the Spanish flu virus, avian H5N1 flu virus, and SARS. It is not unreasonable to think that, in the wrong hands, CRISPR could be used to make dangerous pathogens even more potent.

“Ensuring that CRISPR/Cas does not become touted as a panacea for all genetic illness is crucial for proper application and dissemination of the technology”

The use of technology to increase the pathogenicity of bacterial or viral disease agents falls under the purview of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC), an international treaty designed to prevent the creation and storage of biological weapons. However, the BWC covers state actors—at least those who have signed it—but it was not designed to address private companies or individuals. Moreover, as the tools needed to design and manipulate pathogenic organisms and the exact genetic sequences and instructions to do so become more readily available, the effectiveness of the BWC to prevent the misuse of biological tools and knowledge is increasingly limited.

One way to achieve some control would be to regulate the tools of synthetic biology, notably DNA synthesis. Many companies that offer DNA primers, molecules, or even whole-genome synthesis already monitor orders for specific sequences from pathogenic organisms. While this is an important move by industry to prevent misuse, it does not include all companies; moreover, an increasing number of companies are expanding their customer base beyond academia and industry to private individuals. One possibility to address this problem is to take the industry’s voluntary commitment further and create an international clearinghouse with which genetic sequence producers and sellers must register. It would require all registered companies to monitor their orders and make sure that those who order biological material that could be misused have appropriate credentials, containment facilities, and training.

Much of the discussion about the risks of CRISPR technology has focused on using it to edit the human germ line. Yet, CRISPR has many potential therapeutic applications beyond this specific use, ranging from cancer immunotherapy to treating infectious diseases, to creating stem cell models of disease. These applications constitute genetic editing of human somatic cells and the changes made are therefore not heritable. In cancer immunotherapy, current research focuses on adoptive cell therapies, wherein T cells are harvested from patients, modified ex vivo to increase their potential to destroy tumor cells, expanded in number, and infused back into patients. One particularly promising approach involves chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells, which are engineered to express receptors with the specificity of monoclonal antibodies on their surface. CAR-T therapeutics have proven to be particularly effective in trials against acute lymphoblastic leukemia in both adults and children. As researchers work to elucidate the mechanism by which these therapies achieve a robust response in order to optimize these cells to survive and carry out their effector function in vivo, CRISPR is becoming an attractive option to edit the properties of CAR-T cells. Another therapeutic application of CRISPR might help to cure latent infections with HIV or herpes viruses by targeting and “cutting out” viral DNA in infected human cells.

With the rapid application of CRISPR/Cas in clinical research, it is important to consider the ethical implications of such advances. Pertinent issues include accessibility and cost, the need for controlled clinical trials with adequate review, and policies for compassionate use. Many cell-based therapies come at a considerable cost, particularly patient-specific immunotherapies and stem cell treatments. Adding customized gene editing on top of that will further push the price of such treatments well out of the reach of those with average means and insurance, to say nothing of those who are uninsured, destitute, or rely on national health services to decide what is to be made available to patients. It also raises the issue of educating patients to secure informed consent for research trials and clinical use. CRISPR/Cas can be a tricky concept to explain, especially concerning its subtleties and potential for off-target genome editing.

As excitement over CRISPR grows, so will demand from patients. Balancing requests from patients desperate for novel treatments with the need for rigorous clinical trials is already a challenge for regulators and will not become easier with the advent of CRISPR. US, European, and corporate policies provide some guidance on when and how to allow compassionate use or expanded access to experimental treatments, but these may have to be adapted to address gene editing. Moreover, and as we have seen with stem cell therapies, there are always those willing to promote misinformation or exaggerate in order to profit from desperate patients and their families. Ensuring that CRISPR/Cas does not become touted as a panacea for all genetic illness is crucial for proper application and dissemination of the technology.

There are specific regulatory challenges and ethical issues pertinent to the various applications of CRISPR technology to edit both somatic and germ line human cells. Far more worrisome, however, is the emerging application of CRISPR to non-human organisms. The ability to design first-generation organisms with desired characteristics might encourage development without sufficient containment mechanisms, or result in the premature environmental release of those organisms and loss of control over their spread. In addition, CRISPR could be co-opted for nefarious purposes, such as bioterrorism or biowarfare. The ease and efficiency of CRISPR raises the concern that anyone with the appropriate equipment could engineer a vaccine-resistant flu virus or invasive species in a crude laboratory. While the new technology has sparked important debate about whether to proceed with human germ line engineering, the risks of the applications described here should serve as a call for discussing domestic and international regulation and guidelines for CRISPR’s use.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sidebar A: Further reading.

On using CRISPR/Cas to edit the human germ line:

Baltimore D, Berg P, Botchan M, Carroll D, Charo RA, Church G, Corn JE, Daley GQ, Doudna JA, Fenner M, Greely HT, Jinek M, Martin GS, Penhoet E, Puck J, Sternberg SH, Weissman JS & Yamamoto KR (2015) Biotechnology. A prudent path forward for genomic engineering and germline gene modification. Science 348: 36–38

Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, Lv J, Xie X, Chen Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Bai Y, Songyang Z, Ma W, Zhou C & Huang J (2015) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell 6: 363–372

On editing plants and animals, in particular mosquitos

Alvarez L (2015) A mosquito solution (more mosquitoes) raises heat in Florida Keys. The New York Times 19 Feb. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/20/us/battle-rises-in-florida-keys-over-fighting-mosquitoes-with-mosquitoes.html

Harris AF, Nimmo D, McKemey AR, Kelly N, Scaife S, Donnelly CA, Beech C, Petrie WD & Alphey L (2011) Field performance of engineered male mosquitoes. Nat Biotechnol 29: 1034–1037

Camacho A, Van Deynze A, Chi-Ham C & Bennett AB (2014) Genetically engineered crops that fly under the US regulatory radar. Nat Biotechnol 32: 1087–1091

Wang S, Zhang S, Wang W, Xiong X, Meng F & Cui X (2015) Efficient targeted mutagenesis in potato by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Cell Rep

Podevin N, DEevos Y, Davies HV, Nielsen KM (2012) Transgenic or not? No simple answer. EMBO Rep 13: 1057–1061

Paarlberg R (2010) GMO foods and crops: Africa’s choice. Nat Biotechnol 27: 609–613”

References

- Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanphier E, Urnov F, Haecker SE, Werner M, Smolenski J. Don’t edit the human germ line. Nature. 2015;519:410–411. doi: 10.1038/519410a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman J. Ethics and germline gene editing. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:879–880. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford H. CRISPR, the disruptor. Nature. 2015;522:20–24. doi: 10.1038/522020a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P, Volz SE, Joung J, van der Oost J, Regev A, et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdren J, Shelanski H, Vetter D, Goldfuss C. Improving transparency and ensuring continued safety in biotechnology. Off Sci Technol Policy. 2015 Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2015/07/02/improving-transparency-and-ensuring-continued-safety-biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Larson C. Genome Editing: the ability to create primates with intentional mutations could provide powerful new ways to study complex and genetically baffling brain disorders. MIT Technol Rev. 2014 Available at: http://www.technologyreview.com/featuredstory/526511/genome-editing/ [Google Scholar]

- Oye KA, Esvelt K, Appleton E, Catteruccia F, Church G, Kuiken T, Lightfoot SB-Y, McNamara J, Smidler A, Collins JP. Biotechnology. Regulating gene drives. Science. 2014;345:626–628. doi: 10.1126/science.1254287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt KM, Smidler AL, Catteruccia F, Church GM. Concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations. Elife. 2014;3:e03401. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] 2014. The Guidance Framework for testing genetically modified mosquitoes. Available at: http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/year/2014/guide-fmrk-gm-mosquit/en/