Abstract

Objectives

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently added medication adherence to antihypertensives, antihyperlipidemics, and oral antihyperglycemics to its Medicare STAR quality measures. These CMS metrics exclude patients with <2 medication fills (i.e. “early non-adherence”) and patients concurrently taking insulin. This study examined the proportion of diabetes patients prescribed cardiovascular disease (CVD) medications excluded from STAR adherence metrics, and assessed the relationship of both STAR-defined adherence and exclusion from STAR metrics with CVD risk factor control.

Study Design

Cross-sectional, population-based analysis of 129,040 diabetics ≥65 in 2010 from three Kaiser Permanente regions.

Methods

We estimated adjusted risk ratios to assess the relationship between achieving STAR adherence, and exclusion from STAR adherence metrics, with CVD risk factor control(A1c<8.0%, LDL-C<100mg/dL, systolic blood pressure (SBP)<130mmHg) in diabetics.

Results

STAR metrics excluded 27% of diabetes patients prescribed oral medications. STAR-defined non-adherence was negatively associated with CVD risk factor control (RR=0.95, 0.84, 0.96 for A1c, LDL-C, and SBP control; p<0.001). Exclusion from STAR metrics due to early non-adherence was also strongly associated with poor control (RR=0.83, 0.56, 0.87 for A1c, LDL-C, and SBP control; p<0.001). Exclusion for insulin use was negatively associated with A1c control (RR=0.78; p<.0001).

Conclusion

Medicare STAR adherence measures underestimate the prevalence of medication non-adherence in diabetes, and exclude patients at high risk for poor CVD outcomes. Up to 3 million elderly diabetes patients may be excluded from these measures nationally. Quality measures designed to encourage effective medication use should focus on all patients treated for CVD risk.

Introduction

The Medicare STAR program was designed by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to monitor health care quality in health plans with Medicare enrollees1,2. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) authorized CMS to provide significant monetary and enrollment incentives to Medicare Advantage plans that perform well on these Medicare STAR measures, covering domains ranging from clinical outcomes to patient-reported quality of life1,2. In 2012, CMS introduced 3 new metrics to the Medicare STAR portfolio: medication adherence to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARBs) to control hypertension; statins to control LDL-cholesterol (LDL-c); and oral antihyperglycemics to control HbA1c levels. These novel quality measures emphasize the responsibility of health care plans to monitor and improve medication adherence in their patients2; prior to 2012, most health plans did not systematically measure medication adherence at the population level or report adherence externally. Since diabetes patients account for almost all antihyperglycemic use, and comprise a significant portion of patients prescribed antihypertensives and statins3–5, it is important to understand the impact of this new quality measurement initiative on the diabetes population.

The CMS-defined specifications for the Medicare STAR adherence metric explicitly require at least two prescription fills in the measurement year to calculate adherence6. Patients who never fill an ordered prescription or obtain only a single fill in the measurement year are therefore excluded from the STAR metric. These excluded patients, who are exhibiting evidence of ‘early non-adherence’ to medications7–9, may be at high risk of failure to attain treatment goals and optimal clinical outcomes7–9. The Medicare STAR oral antihyperglycemic adherence measure also excludes all patients who are taking oral antihyperglymemic medications from their oral medication adherence measure if they are also taking insulin concurrently. These patients who are intensively treated with both oral and injected medications may also be at high risk for poor cardiovascular (CVD) outcomes10. Since CMS has not published the specific justifications for these exclusions, it is important to understand the ramifications of these specifications for both quality measurement and quality improvement.

While some studies have linked higher adherence to cardiometabolic medications with improved CVD risk factor control and clinical outcomes in diabetes patients7,8,11–19, these studies are largely based on younger populations. The relationship between performance on the new STAR adherence metrics and risk factor control in the Medicare population, and the relationship between exclusion from the STAR metrics and CVD risk factor control, is unknown.

This study is designed to improve our understanding of these novel CMS quality measures by assessing the proportion of Medicare patients with diabetes who are excluded from the Medicare STAR medication adherence metrics due to early non-adherence and insulin use; and by quantifying the relationship between Medicare STAR adherence, early non-adherence, and concurrent insulin use with CVD risk factor control.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

The population for this study was derived from the Surveillance, Prevention, and Management of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) study, a multi-center project to create a data resource for comparative effectiveness, epidemiology, and health services research20. The current study utilized data from three SUPREME-DM sites: Kaiser Permanente (KP) Northern California, KP Colorado, and KP Northwest. These KPs are non-profit, integrated, group-model health care delivery systems collectively serving 4.1 million members in a 13-county area of Northern California, the state of Colorado, Northwest Oregon, and Southwest Washington. The SUPREME-DM DataLink accesses electronic health record (EHR) data as well as other clinical and administrative database information from participating sites20. Data include patient age, birth year, sex, race/ethnicity, census block group socioeconomic status (SES) data, enrollment data; laboratory results (including HbA1c and LDL-C levels); prescription data (including medication orders, fills, dose, days’ supply, NDC codes, and if the medication order was written for an outside-KP pharmacy); and systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements from 2005–2011. Patients were eligible for the current study if they had diabetes in 2010, and were eligible for Medicare (65 years of age or older as of January 1, 2010). Patients were defined as having diabetes if they had two or more outpatient diabetes ICD-9 diagnosis codes (250.xx) within a two year window since the start of 2000.21–23 The small number of patients who had prescription orders for medications to be filled outside of KP in 2010 (~1%) were excluded from the analysis.

Medicare STAR Medication Adherence

We calculated the Medicare STAR adherence metrics following exact CMS specifications to obtain the Medicare STAR Proportion of Days’ Covered (PDC) adherence measure in 2010 for all diabetes patients for each of the three therapeutic groups covered by the measures: ACEI/ARBs, statins, and oral diabetes medications6. These therapeutic groupings are specified for use in calculating the STAR adherence measure by CMS, following recommendations made by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance6. Per CMS specifications, all patients taking these medications are potentially eligible to be included in the measures with no upper age limit or restrictions due to health status (e.g. nursing home residence). CMS bases the Medicare STAR adherence measures on PDC method for calculating adherence6,24, defined as the percent of days in the measurement period “covered” by prescription fills for the same medication or medications in the same therapeutic category. CMS specifies that the measurement period for 2010 begins with patients’ first fill in 2010, and continues through 12/31/2010. As outlined above, the PDC is only calculated for patients with two or more fills in the measurement period: those with fewer than two fills in that period are excluded by CMS and therefore by our calculations as well. This ‘two or more fills’ criteria within a therapeutic grouping to treat a CVD risk factor captures patients who switched medications to address that risk factor within that year, but excludes those who discontinue medications to treat a risk factor after only one fill. The PDC can range from 0–100%; the Medicare STAR adherence measure considers patients to be ‘adherent’ if their PDC is >= 80%.

Medicare STAR Exclusions from the Adherence Metrics

The KP pharmacy ordering and refill systems were used to identify those patients who had a prescription ordered by their clinician in one of the three therapeutic groups in 2010 who never filled it (0 fills), or obtained only a single fill. We then assessed the prevalence of these patients excluded by CMS from the STAR measure due to “early non-adherence”: those with an order but no fills are considered “primary non-adherent”, and those with only one fill but no subsequent fills are considered “early non-persistent.”7 We also created a category for the additional patients excluded from the Medicare STAR oral antihyperglycemic medication category who had two or more fills of an oral antihyperglycemic during the measurement period, but were excluded by CMS specifications due to concurrent insulin use.

Statistical Analyses

To assess the relationship of poor adherence based on the Medicare STAR adherence metric with CVD risk factor control, adjusting for differences in age, race/ethnicity, and other confounding factors also associated with CVD risk factor control, we performed three separate Poisson regression models25 using being in good control for A1c, LDL-c, and SBP (defined as A1c < 8.0%; LDL-c < 100 mg/dL; and SBP < 130 mm/Hg respectively) at the last recorded measurement in 2010 as the dependent variable, and non-adherence of PDC< 80% (compared with PDC >=80%) as the main independent variable. Modified Poisson regressions directly estimate risk ratios when outcomes are common; in these cases, it is not appropriate to report odds ratios from logistic regressions.25–27 To assess the relationship between early non-adherence (i.e. patients excluded by Medicare STAR adherence measures) with CVD risk factor control, we performed three separate Poisson regression models using being in good control for A1c, LDL-c, and SBP at the last recorded measurement in 2010 as the dependent variable, and excluded patients with 0 or 1 fill (compared with patients with PDC >=80%) as the main independent variable. We examined the relationship between A1c control and exclusion from the oral antihyperglycemic measure based on insulin use concurrent with two or more fills of oral diabetes medications (compared with patients who were not using insulin and a PDC >=80% for their diabetes medications) using a separate, similar Poisson regression model. These regression analyses controlled for patient age, gender, race/ethnicity, medication burden (as measured by the overall number of medications a patient was taking at the start of 2010), length of enrollment in the health plan during 2010, and mean days’ supply of medications in each therapeutic grouping corresponding to the risk factor control of interest as predictor variables.

All analyses were performed using Stata v10.1. The lead author (Dr. Schmittdiel) designed the study and wrote the manuscript; Ms. Wendy Dyer (third author) analyzed the data. This study was approved by each KP region’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Among the 129,040 eligible patients in the sample, close to 25% of the sample were ages 80 and above; 49.4% were female; and 58.8% were white (Table 1). 73.9% of patients had at least one ACEI/ARB prescription order or fill in 2010, while 80.4% had an order or fill for a statin, and 61.0% had an order or fill for an oral diabetes medication. In general, patients excluded from the STAR metrics were older, less likely to be non-Hispanic white, and have a higher level of comorbidity burden (Table 1b.)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | 129,040 | 100% |

| Age | ||

| 65–69 | 38,298 | 29.7% |

| 70–74 | 32,823 | 25.4% |

| 75–79 | 26,475 | 20.5% |

| 80–84 | 18,442 | 14.3% |

| 85+ | 13,002 | 10.1% |

| Female | 63,689 | 49.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 444 | 0.3% |

| Asian | 13,306 | 10.3% |

| Black | 10,063 | 7.8% |

| Hispanic | 16,492 | 12.8% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 633 | 0.5% |

| White | 75,880 | 58.8% |

| Race Missing/Unknown | 12,222 | 9.5% |

| Enrolled for 12 months | 119,777 | 92.8% |

| Anxiety | 6,295 | 4.9% |

| Arthritis | 31,650 | 24.5% |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 13,114 | 10.2% |

| COPD | 11,879 | 9.2% |

| Depression | 16,655 | 12.9% |

| Heart Failure | 15,309 | 11.9% |

| Poorly Controlled Hyperlipidemia (LDL≥100) | 23,104 | 17.9% |

| Poorly Controlled Hypertension (SBP≥130) | 47,611 | 36.9% |

| Poorly Controlled Hyperglycemia (A1c≥8%) | 14,539 | 11.3% |

| Insulin Use | 27,945 | 21.7% |

| Fills or Orders in 2010 for ACEI/ARB | 95,395 | 73.9% |

| Fills or Orders in 2010 for Statin | 103,808 | 80.4% |

| Fills or Orders in 2010 for Oral Diabetes Drug | 78,743 | 61.0% |

| Mean Number of Medications at Study Start (Std Dev) | 5.32 (3.49) | |

| Mean Days Supply of ACEI/ARB (Std Dev) | 91.28 (17.91) | |

| Mean Days Supply of Statins (Std Dev) | 89.15 (17.22) | |

| Mean Days Supply of Oral DM Drugs (Std Dev) | 89.83 (18.82) |

| Table 1b. Patient Characteristics by Whether Included in Medicare STAR Medication Adherence Metric | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ACEI/ARB Fills or Orders in 2010 (n=95,395) |

Patients with Oral Diabetes Drug Fills or Orders in 2010 (n=78,743) |

Patients with Statin Fills or Orders in 2010 (n=103,808) |

|||||||

| Adherent: PDC≥80% |

Non- adherent: PDC<80% |

Excluded | Adherent: PDC≥80% |

Non- adherent: PDC<80% |

Excluded | Adherent: PDC≥80% |

Non- adherent: PDC<80% |

Excluded | |

| n (%) | 69,402 (73%) | 16,718 (17%) | 9,275 (10%) | 46,406 (59%) | 10,223 (13%) | 22,114 (28%) | 73,582 (71%) | 19,694 (19%) | 10,532 (10%) |

| Age | |||||||||

| 65–69 | 32% | 30%*** | 30%*** | 33% | 31%* | 35%*** | 30% | 32%*** | 31% |

| 70–74 | 27% | 26%** | 24%*** | 27% | 25%*** | 27% | 27% | 26% | 25%*** |

| 75–79 | 21% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 19%** | 21% | 20%*** | 19%*** |

| 80–84 | 13% | 14%*** | 14%*** | 13% | 14%*** | 12%*** | 14% | 14% | 14% |

| 85+ | 7% | 10%*** | 12%*** | 7% | 10%*** | 7%* | 8% | 9%** | 11%*** |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 60% | 56%*** | 55%*** | 56% | 52%*** | 59%*** | 61% | 54%*** | 52%*** |

| Hispanic | 12% | 15%*** | 14%*** | 13% | 15%*** | 15%*** | 12% | 15%*** | 15%*** |

| Asian | 11% | 11% | 12%* | 13% | 11%*** | 10%*** | 11% | 11% | 12% |

| Race Missing/Unknown | 10% | 9%** | 10% | 11% | 11% | 8%*** | 9% | 10% | 11%*** |

| Black | 7% | 9%*** | 9%*** | 7% | 10%*** | 8%*** | 7% | 10%*** | 10%*** |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1%* | <1%* |

| Female | 49% | 51%** | 48%** | 48% | 51%*** | 48% | 48% | 52%*** | 51%*** |

| Anxiety | 4% | 5%*** | 5%** | 4% | 5%*** | 4%** | 4% | 6%*** | 5%*** |

| Arthritis | 24% | 25% | 23%*** | 23% | 24%* | 23% | 25% | 25% | 23%*** |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 9% | 10%** | 11%*** | 8% | 8% | 10%*** | 10% | 9%** | 9%** |

| COPD | 8% | 10%*** | 11%*** | 7% | 9%*** | 10%*** | 9% | 10%*** | 9% |

| Depression | 12% | 14%*** | 14%*** | 10% | 12%*** | 15%*** | 12% | 15%*** | 13%*** |

| Heart Failure | 10% | 14%*** | 15%*** | 8% | 9%*** | 14%*** | 11% | 13%*** | 13%*** |

p-value <.05,

p-value<.01,

p-value<0.001

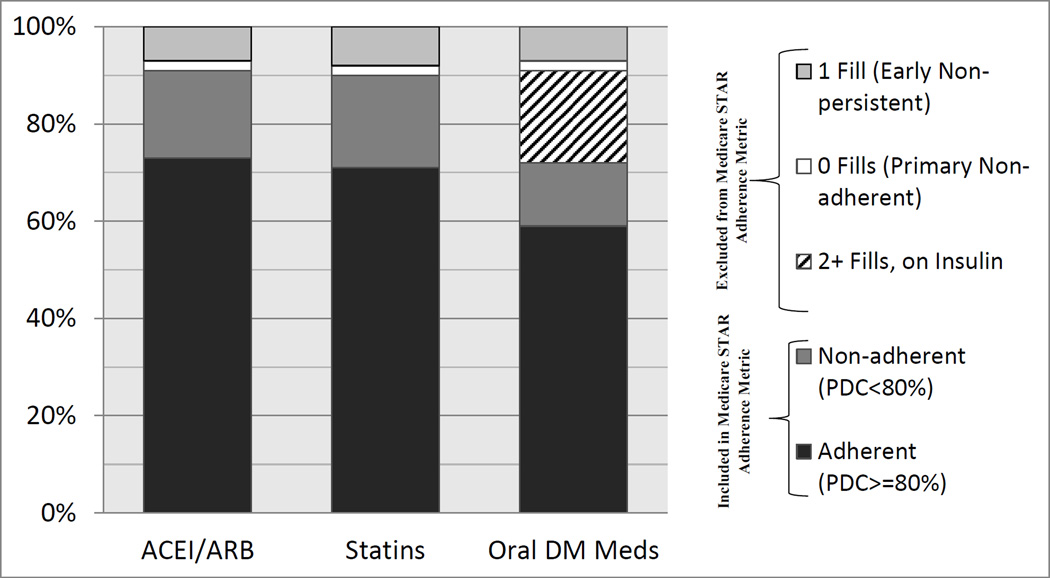

Figure 1 shows the percent of patients who were adherent based on the Medicare STAR metric, and those with evidence of a cardiometabolic medication prescription in 2010 who were excluded from the Medicare STAR adherence metric based on the CMS measurement specifications. Among all individuals receiving an order or prescription, 73%, 71%, and 59% of patients were adherent based on STAR criteria to ACEI/ARBs, statins, and oral diabetes medications respectively. When the patients excluded by Medicare STAR are not included in the adherence calculations, 80.6%, 78.9%, and 81.9% of patients were adherent to ACEI/ARBS, statins, and oral diabetes medications respectively (data not shown.) A total of 9% of patients prescribed a medication in the ACEI/ARB therapeutic grouping were considered “primary non-adherent” and did not fill their medication at all (2%) or were “early non-persistent” and filled only once (7%) (and were therefore excluded by CMS); among those patients on a statin, 10% were excluded (2% for having 0 fills of an ordered medication, and 8% for having 1 fill.)

Figure 1.

Patients with Medication Orders Or Fills in 2010

Twenty-eight percent of patients who were ordered an oral diabetes medication were excluded: 2% due to never filling an ordered medication; 7% for filling only once; and 19% because they had filled the oral medication at least twice in 2010 but also had at least one fill for insulin. A total of 34,514 unique patients (27%) of the patients in our diabetes cohort were excluded from all medication adherence monitoring by the STAR measures, based on CMS criteria.

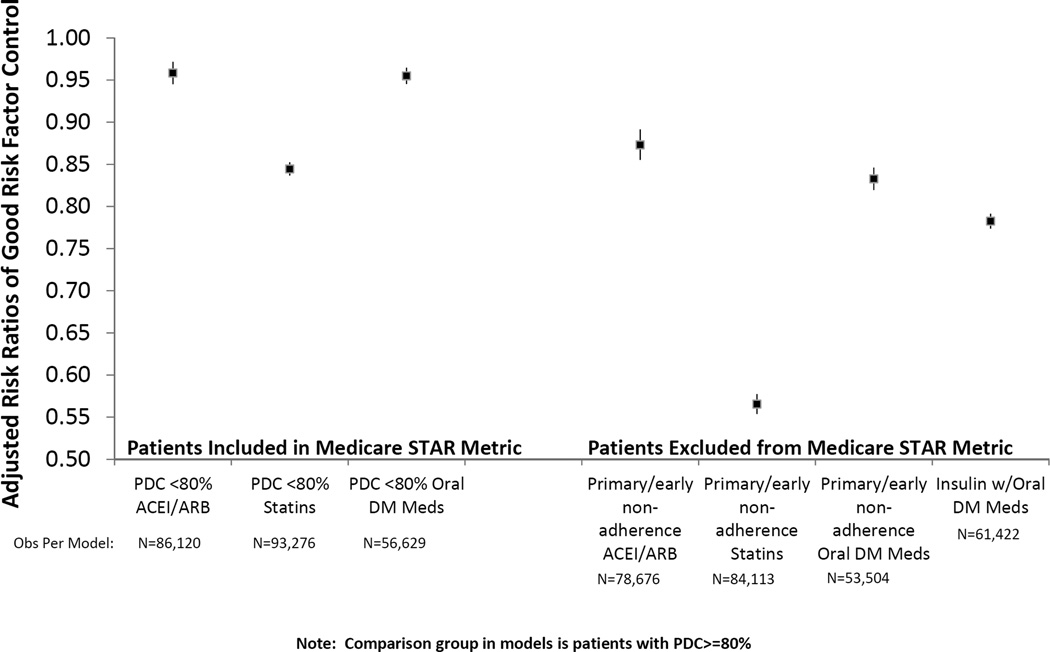

Patients who were adherent to medications based on the Medicare STAR metric had higher CVD risk factor control than either those who were non-adherent based on the STAR metric, and those who were excluded from the STAR metric, in all three therapeutic groupings of CVD risk factor medications (Table 2). After adjustment, non-adherence based on the STAR metric was associated with suboptimal CVD risk factor control: (RR=0.95 (95% CI=0.94,0.96), RR=0.84 (CI=0.83,0.85), and RR=0.96 (CI=0.95,0.96) for A1c, LDL-C, and SBP control respectively (Figure 2). Exclusion from the STAR metric based on early non-adherence was also negatively associated with risk factor control: RR=0.83 (CI=0.82,0.85), RR=0.56 (CI=0.55,0.58), RR=0.87 (CI=0.86,0.89) for A1c, LDL-C, and SBP control respectively. Exclusion from the STAR metric for concurrent insulin use was negatively associated with A1c control among patients ordered or filling oral diabetes medications: RR=0.78, CI=(0.77,0.79).

Table 2.

Risk Factor Control Rates† for Patients with Medication Fills or Orders in Relevant Therapeutic Category (TC) in 2010

| SBP < 130 (TC= ACEI/ARB) |

A1c < 8% (TC= Oral DM) |

LDL < 100 (TC=Statins) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Included in Medicare STAR Adherence Metric: | |||

| Adherent (PDC≥80%) | 64% | 87% | 87% |

| Non-adherent (PDC<80%) | 60% | 80% | 71% |

| Excluded from Medicare STAR Adherence Metric: | |||

| 0 Fills (Primary Non-adherent) | 52% | 69% | 43% |

| 1 Fill (Early Non-persistent) | 55% | 69% | 48% |

| 2+ Fills, on Insulin | n/a | 69% | n/a |

Based on last recorded measurement in 2010

Figure 2.

Good Risk Factor Control Least Likely Among Patients Excluded from Medicare STAR Metric

Note: Comparison group in models is patients with PDC>=80%

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the levels of medication adherence in Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes based on the new CMS Medicare STAR adherence metrics, and to assess the proportion of patients excluded from these metrics. In a cohort of 129,040 patients age 65 or older, we found that between 59% and 71% of patients who had evidence their physician had put them on a medication were considered adherent by the CMS metric depending on therapeutic grouping. However, between 9% and 28% of these patients were excluded from the STAR adherence measures by CMS. The CMS specifications excluded 27% of our overall diabetes cohort of patients aged 65 and up from being covered by any of these measures. Since current government estimates find that up to 10.8 million Americans age 65 and above have diabetes28–29, our study suggests that up to 2.93 million Medicare-aged diabetes patients may be excluded from these measures nationally. It is unclear why CMS chose these particular exclusion criteria; for example, while measuring insulin adherence might require different data and methods, the oral diabetes medication adherence for those patients concurrently taking insulin can be measured using the current PDC-based methodology. Further discussion with CMS as to the rationale for excluding these patients, and finding a path towards monitoring the quality of CVD risk factor management in these exclude patients, has the potential to improve care for millions of diabetes patients.

Adherence to medications is a process measure for assessing the quality of health care, since it does not measure clinical outcomes directly30. The most meaningful process measures of health care quality should be ‘tightly linked’ to clinical outcomes31; in this case, attempts to measure the process of taking CVD risk factor medications appropriately should be strongly correlated with CVD risk factor control. Our study shows that the Medicare STAR adherence metrics do achieve this linkage with CVD risk factor control among patients covered by the measure. However, our study also demonstrates that exclusion from the metric based on early non-adherence is also strongly associated with poor CVD risk factor control. These findings add to the evidence base suggesting that the underuse of cardiometabolic medications is a significant barrier to CVD risk factor control in diabetes patients32, and suggest that the current STAR measures underestimate medication non-adherence in the diabetes population. Currently, the difference between a 5-star rating for adherence to oral antidiabetes medications and a 3-star rating for Medicare Advantage plans is less than 5% (>=79% adherent vs. <75.7% adherent)6. While changes to the way CMS measures adherence that would account for early non-adherence could temporarily lower health plan ratings on these measures, considering the importance of high STAR ratings to health plans33 these changes would likely encourage plans to address early non-adherence among their enrollees. Quality measures focused on adherence should also take underuse of medications due to not starting or not refilling a prescribed medication into account.

The new STAR adherence metrics place an important and innovative emphasis on holding health plans accountable for appropriate medication adherence. As a response to this mandate, CMS and health plans caring for Medicare enrollees should focus on implementing and disseminating system-level interventions to help patients successfully start medications, as well as encourage ongoing medication persistence in those who have achieved 2 fills or more2,8,17,34. Research suggests that effective interventions to improve medication starts and ongoing medication adherence are available; for example, one recent study showed that automated outreach to early non-adherent patients can successfully improve statin starts and refill rates.33 These types of interventions, when cost-effective, have great potential as health care systems move towards greater integration and meaningful use of electronic health information36–38.

This analysis has a few limitations worth noting. All patients in this study had diabetes; the Medicare STAR adherence measures will also be applied to patients with hypertension or hyperlipidemia who do not have diabetes. The level of adherence based on Medicare STAR measure specifications in these large, integrated delivery systems was generally high, and these systems also achieve consistently high scores on other Medicare STAR metrics39; the level of Medicare STAR adherence and early non-adherence to medications may be different in other health care settings. In addition, currently not all health plans engaged in reporting to CMS have access to electronic health record prescription data. However, since KP system characteristics such as integration and meaningful use of electronic health care data are put forth as models of care by the ACA and other recent legislation36–38, and health plans will be moving to electronic health records based on these requirements, these findings provide a significant benchmark for medication adherence standards moving forward. In addition, we do not have data on why patients may have discontinued medications after only one fill, and were then therefore excluded from the Medicare STAR metric.

We were not able to measure medication adherence for a substantial proportion of patients with diabetes because they had no evidence they were placed on a CVD risk factor control medication by their physician (i.e. no prescription orders or fills in 2010). As shown in Table 1, 19.6% of diabetes patients had no evidence they were prescribed statins; 26.1% had no evidence they were prescribed ACEI/ARBs, and 39.0% showed no evidence they were prescribed oral diabetes medications. Medication adherence metrics would not be appropriate for monitoring quality of care in these patients; however, whether risk factors in these patients were being managed through lifestyle interventions alone, or whether due to age or other comorbidities these medicines were not indicated for CVD risk factor control, is unknown. Future research should focus on developing quality metrics that monitor quality for a wide range of CVD risk factor control efforts in Medicare-aged diabetes patients that take the needs of older patients with multiple comorbidities into account.

Conclusions

While higher STAR-defined adherence is associated with CVD risk factor control, this new measure excludes a significant number of diabetes patients prescribed cardiometabolic medications that are at high risk for poor CVD outcomes. Health care policies that encourage system-level efforts to address the underuse of medications in diabetes patients should focus on decreasing CVD risk for the entire population of Medicare patients, including those now excluded from the new STAR adherence metrics.

Take-Away Points.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently added cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor medication adherence to its Medicare STAR quality measures. These measures exclude patients with <2 medication fills, and diabetes patients concurrently taking insulin. We found:

27% of diabetes patients prescribed oral medications were excluded from the measures.

Excluded diabetes patients were significantly likely to have poor CVD risk factor control.

3 million elderly diabetes patients may be excluded from these measures nationally.

Medicare STAR adherence measures underestimate non-adherence in diabetes.

Quality measures designed to encourage effective medication use should focus on all patients treated for CVD risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the Kaiser Permanente Center for Effectiveness and Safety Research, Contract no. KR021125. This project was supported by grant number R01HS019859 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This activity was also supported by the Health Delivery Systems Center for Diabetes Translational Research (CDTR) [NIDDK grant 1P30-DK092924].

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. Reaching for the Stars: Quality Ratings of Medicare Advantage Plans, 2011. [Accessed October 2, 2012]; Issue Brief. http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8151.pdf.

- 2.Steiner JF. Rethinking adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Oct 16;157(8):580–585. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wienbergen H, Senges J, Gitt AK. Should we prescribe statin and aspirin for every diabetic patient? Is it time for a polypill? Diabetes Care. 2008 Feb;31(Suppl 2):S222–S225. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson ML, Singh H. Patterns of antihypertensive therapy among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Sep;20(9):842–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konzem SL, Devore VS, Bauer DW. Controlling hypertension in patients with diabetes. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Oct 1;66(7):1209–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Health and Drug Plan Quality and Performance Ratings, 2013 Part C and Part D Technical Notes. 2012 Sep 6; Draft. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Ahmed AT, Schmittdiel JA, Selby JV. New prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptions. Health Serv Res. 2009 Oct;44(5 Pt 1):1640–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams AS, Uratsu C, Dyer W, et al. Health System Factors and Antihypertensive Adherence in a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Cohort of New Users. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Dec 10;:1–8. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raebel MA, Carroll NM, Ellis JL, Schroeder EB, Bayliss EA. Importance of including early nonadherence in estimations of medication adherence. Ann Pharmacother. 2011 Sep;45(9):1053–1060. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder EB, Hanratty R, Beaty BL, Bayliss EA, Havranek EP, Steiner JF. Simultaneous control of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in 2 health systems. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012 Sep 1;5(5):645–653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Karter AJ, et al. Why don't diabetes patients achieve recommended risk factor targets? Poor adherence versus lack of treatment intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 May;23(5):588–594. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Fireman BH, Selby JV. The effectiveness of diabetes care management in managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2009 May;15(5):295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, Thumula V, Pace PF, Banahan BF, 3rd, Wilkin NE, Lobb WB. Predictors of medication nonadherence among patients with diabetes in Medicare Part D programs: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ther. 2009 Oct;31(10):2178–2188. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.10.002. discussion 2150–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiegand P, McCombs JS, Wang JJ. Factors of hyperlipidemia medication adherence in a nationwide health plan. Am J Manag Care. 2012 Apr;18(4):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker EA, Molitch M, Kramer MK, et al. Adherence to preventive medications: predictors and outcomes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2006 Sep;29(9):1997–2002. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, et al. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Dec;26(12):1396–1402. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005 Jun;43(6):521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau DT, Nau DP. Oral antihyperglycemic medication nonadherence and subsequent hospitalization among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004 Sep;27(9):2149–2153. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichols GA, Desai J, Elston Lafata J, et al. Construction of a multisite DataLink using electronic health records for the identification, surveillance, prevention, and management of diabetes mellitus: the SUPREME-DM project. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E110. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care. 2004 May;27(Suppl 2):B10–B21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor PJ, Rush WA, Pronk NP, Cherney LM. Identifying diabetes mellitus or heart disease among health maintenance organization members: sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, and cost of survey and database methods. Am J Manag Care. 1998 Mar;4(3):335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zgibor JC, Orchard TJ, Saul M, et al. Developing and validating a diabetes database in a large health system. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007 Mar;75(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Proportion of Days Covered. [Accessed August 6, 2011]; http://www.pqaalliance.org/files/Proportion%20of%20Days%20Covered%202010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kind AJH, Bartels C, Mell MW, Mullahy J, Smith M. For-profit hospital status and rehospitalizations to different hospitals: an analysis of Medicare data. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Dec 7;153(11):718–727. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-11-201012070-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knol MJ, Le Cessie S, Algra A, Vandenbroucke JP, Groenwold RHH. Overestimation of risk rations by odds ratios in trials and cohort studies: alternatives to logistic regression. CMAJ. 2012 May 15;184(8):895–899. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get the Facts on Diabetes. [Accessed January 15, 2013]; http://www.cdc.gov/features/diabetesfactsheet/.

- 29.United States Department of Commerce. Older Americans Month: May 2012. [Accessed January 15, 2013];2012 http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb12-ff07.html.

- 30.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerr EA, Smith DM, Hogan MM, et al. Building a better quality measure: are some patients with 'poor quality' actually getting good care? Med Care. 2003 Oct;41(10):1173–1182. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000088453.57269.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998 Sep 16;280(11):1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Shrank WH. Association between Medicare Advantage plan star ratings and enrollment. JAMA. 2013 Jan 16;309(3):267–274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.173925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duru OK, Schmittdiel JA, Dyer WT, et al. Mail-order pharmacy use and adherence to diabetes-related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2010 Jan;16(1):33–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derose SFGK, Marrett E, Tunceli K, Cheetham TC, Chiu VY, Harrison TN, Reynolds K, Vansomphone SS, Scott RD. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to chloresterol-lowering medications. Arch Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcotte L, Seidman J, Trudel K, et al. Achieving meaningful use of health information technology: a guide for physicians to the EHR incentive programs. Arch Intern Med. 2012 May 14;172(9):731–736. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rittenhouse DR, Thom DH, Schmittdiel JA. Developing a policy-relevant research agenda for the patient-centered medical home: a focus on outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Jun;25(6):593–600. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1289-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care--two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 10;361(24):2301–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser Permanente. [Accessed January 16, 2013]; https://medicare.kaiserpermanente.org/wps/portal/medicare/promo/ncal?WT.mc_id=112098&WT.srch=1&WT.seg_1=PF-4-sviMcIRva-pcrid-16748236844-kp%20medicare-p. [Google Scholar]