Introduction

The prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients is a significant healthcare problem with implications for patient outcomes 1-5. Malnutrition appears to be an independent predictor of outcome and is associated with a higher rate of infectious and non-infectious complications, increased mortality, longer length of hospital stay and increased hospital costs 5. Malnutrition in hospitalized children is associated with altered physiological responses, increased resource utilization and influences outcome during critical illness 9, 10. Among, critically ill children, the prevalence of malnutrition has remained unchanged over the past three decades 7, 8. Critical illness itself may increase metabolic demand on the host in the early stages of the stress response and nutrient intake may be limited. Thus, children admitted to the PICU are at a risk of worsening nutritional status and anthropometric changes that may be associated with morbidity 11.

Despite its high prevalence and consequences, medical awareness of malnutrition is lacking. Only a small fraction of hospitalized patients are assessed for nutritional status or referred for nutrition support 12. Careful nutritional evaluation at admission to the PICU is essential for identification of children at risk for further nutritional deterioration and may allow interventions to optimize nutrient intake with a potential for improving outcomes. The epidemiology and etiology of malnutrition in critically ill children are described here. The importance of nutritional assessment and measures to prevent nutritional deterioration of children in the PICU are discussed in this manuscript.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Malnutrition in the PICU

One in every five children admitted to the PICU suffers from acute and/or chronic malnutrition 3, 7, 8. Due to the lack of systematic nutrition assessment at many centers, the true extent of the problem of malnutrition in the PICU population may not be appreciated. The correlation between nutritional status and outcomes is complex and probably bidirectional 13. On one hand, underlying disease state and the duration of pre-PICU illness may influence the severity of malnourishment and predispose some children to critical illness. On the other hand, the increased energy demands from the metabolic stress response during critical illness, erratic prescription of nutrients and failure to administer adequate nutrients are factors responsible for the subsequent worsening of nutritional status in children admitted to the PICU. Indeed, acute and chronic malnutrition have been shown to worsen at discharge from the PICU 7.

Some critically ill children may be at an increased risk of protein energy malnutrition (PEM). Infants have a high basal metabolic rate and limited energy reserves, and are particularly at risk of developing nutritional deficiencies during illness. Children with congenital heart disease (CHD) have a high incidence of protein energy malnutrition, which contributes to poor outcome in this cohort 14. Common reasons for caloric deficits in children with CHD include, decreased intake, increased energy expenditure (due to cardiac failure or increased work of breathing) and malabsorption (due to increased right-side heart pressure, lower cardiac output, and/or altered gastrointestinal function) 15-18. In a retrospective review of newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome who underwent the traditional Norwood procedure, we have reported a high incidence of PEM manifested by low weight-for-age Z scores 60. Following initial hospitalization in the first month of life, weight for- age Z scores and weight-for-length Z scores decreased over time, and half the infants were severely underweight when readmitted for major cardiac surgery. Longer length of hospital or PICU stay, and frequency of readmissions were significantly correlated with poor nutritional status in this cohort. In children with severe burns, the hypermetabolic stress response and poor intake results in energy deficits, and the negative effects on nutritional status have been shown to persist for months after injury. Decrease in lean body mass was shown for up to a year after the burn, with delayed linear growth reported up to 2 years after injury 19, 20. In other groups of critically ill children, recovery of nutritional status has been more encouraging 7. Duration of PICU-stay is an important factor associated with the development of cumulative energy and protein deficits in critically ill children 11. The development of deficits is most rapid during the first few days after admission. Duration of mechanical ventilation and need for surgical intervention are other factors associated with development of cumulative energy deficits, independent of PICU-stay.

Etiology of Malnutrition N Critically Ill Children

The etiology of malnutrition developing during critical illness is multifactorial, and common factors contributing to the protein and caloric deficits during the PICU course include; (A) increased energy demands secondary to the metabolic stress response, (B) failure to accurately estimate energy expenditure and (C) inadequate substrate delivery at the bedside.

(A). The Metabolic Stress Response

The profound and stereotypic metabolic response to critical illness in children is not always predictable, and varies in intensity and duration between individuals. The caloric burden imposed by the metabolic response to injury, surgery or inflammation may be proportional to the severity and duration of the stress but cannot ne accurately estimated. Nutritional support cannot reverse or prevent the metabolic stress response. However, failure to provide optimal calories and protein during the acute stage of illness could result in exaggeration of existing nutritional deficiencies or result in new onset malnutrition. The large energy imbalances secondary to both under and overfeeding in critically ill children must be avoided 21. This requires an individualized nutritional regimen that must be tailored for each child and reviewed regularly during the course of illness. A basic understanding of the metabolic events that accompany critical illness and surgery is essential for planning appropriate nutritional support in critically ill children.

The unique hormonal and cytokine profile manifested during critical illness is characterized by an elevation in serum levels of insulin, glucagon, cortisol, catecholamines, and proinflammatory cytokines 28. Increased serum counter-regulatory hormone concentrations induce insulin and growth hormone resistance, resulting in the catabolism of endogenous stores of protein, carbohydrate, and fat to provide essential substrate intermediates and energy necessary to support the ongoing metabolic stress response 28.

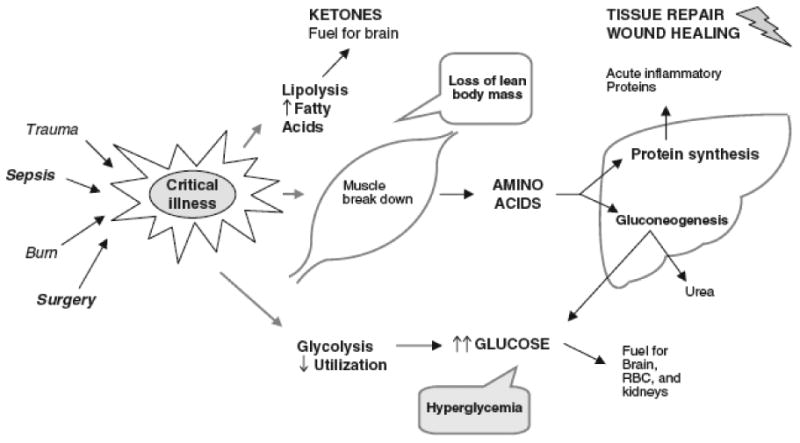

Figure 1 illustrates the basic pathways involved in the metabolic stress response. In general, the net increase in muscle protein degradation, characteristic of the metabolic stress response, results in a large amount of free amino acids in the circulation. Free amino acids are used as the building blocks for the rapid synthesis of proteins that act as inflammatory response mediators and are used for tissue repair. Remaining amino acids not used in this way, are channeled through the liver, where their carbon skeletons are utilized to create glucose through gluconeogenesis. Although, the provision of optimal dietary protein does not eliminate the overall negative protein balance associated with the catabolic response to injury, it may slow the rate of net protein loss 6. Carbohydrate turnover is simultaneously increased during the metabolic response, with significant increase in glucose oxidation, and gluconeogenesis 16. However, the administration of exogenous glucose does not blunt the elevated rates of gluconeogenesis, and net protein catabolism continues unabated 14. A combination of dietary glucose and protein may improve protein balance during critical illness, primarily by enhancing protein synthesis. The stress response is also characterized by increased rates of fatty acid oxidation 93. As seen with the other catabolic changes associated with stress response, the provision of dietary glucose does not decrease fatty acid turnover in times of illness. The increased demand for lipid utilization in the setting of limited lipid stores puts the metabolically stressed neonate or previously malnourished child at high risk for the development of essential fatty acid deficiency 95, 96. Preterm infants are most at risk for developing essential fatty acid deficiency after a short period fat-free nutritional regimen 97.

Figure 1.

Basic pathways of the metabolic stress response to injury

The metabolic alterations during critical illness may be dynamic and change during the course of illness. A wide range of metabolic states have been observed in mechanically ventilated children with an average early tendency towards hypermetabolism 29. Children with severe burn injury demonstrate extreme hypermetabolism in the early stages of injury 30. The standard equations used for estimating energy requirements may underestimate the resting energy expenditure and lead to underfeedin. The failure to provide adequate calories during this phase may lead to the loss of critical lean body mass and worsening of existing malnutrition. Stress or activity correction factors have been traditionally factored into basal energy requirement estimates to adjust for the nature of illness, its severity and the activity level of hospitalized subjects 31, 32. However, decreased activity, decreased insensible fluid losses and transient absence of growth during the acute illness may predispose some critically ill children to the risk of overfeeding 33. The application of a uniform stress correction factor to equation estimated energy requirement in critically ill children may be too simplistic, likely to be inaccurate and increase the risk of overfeeding. Overfeeding is associated with deleterious effects in the critically ill patient 24, 25. It increases ventilatory work by increasing carbon dioxide production and can potentially prolong the need for mechanical ventilation 26. Overfeeding may also impair liver function by inducing steatosis and cholestasis, and increase the risk of infection secondary to hyperglycemia. To account for these dynamic alterations in energy metabolism secondary to an unpredictable stress response, measured resting energy expenditure (REE) values remain the only true guide for energy intake in critically ill children.

(B) Estimation of Energy Requirement during Critical Illness

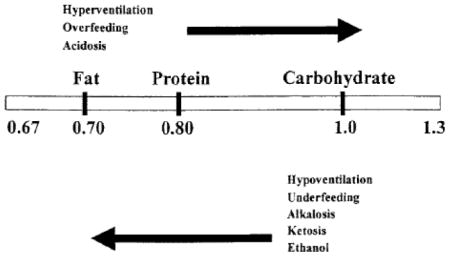

The energy requirements for critically ill children are often derived from commonly used equations based on patient demographics. These equations have been shown to be inaccurate and may underestimate or overestimate the true energy requirements 21, 37-40. Thus, nutrition intake based on estimated requirements often results in both underfeeding and overfeeding. The cumulative effect of inaccurate estimations and suboptimal may result in significant caloric imbalances with potential for affecting outcomes 22, 23. Indirect calorimetry (IC), using a metabolic cart, can be performed at the bedside to measure VO2 (the volume of oxygen consumed) and VCO2 (the volume of CO2 produced). The respiratory quotient (RQ), defined by the ratio VCO2) to VO2, may be affected by extremes of substrate use by the child. Underfeeding, which promotes use of endogenous fat stores, should cause decreases in the RQ, whereas overfeeding, which results in lipogenesis, should cause increases in the RQ 42. However, the use of the respiratory quotient (RQ) as a measure of substrate use in individual patients has a low specificity and cannot be recommended to screen for underfeeding or overfeeding 43. An increasing value of RQ in response to overfeeding has been associated with increased ventilatory demands and respiratory burden and elevation of measured RQ >1.0 may be an indicator of reduced respiratory tolerance of the nutrition regimen 42. A combination of acute phase proteins (CRP) and RQ may reflect transition from the catabolic hypermetabolic to the anabolic state.

To achieve optimal individualized nutrition support, caloric goals should be identified regularly in critically ill children with the help of IC when feasible. With careful attention to its limitations and available expertise with its interpretation, IC can be applied in a PICU and is indeed warranted in children at high risk for underfeeding and overfeeding 31, 32. However, resource constraints and lack of available expertise restricts the regular use of Indirect Calorimetry (IC) in the PICU. In a multicenter study of nutrition practices in the PICU, a majority of European centers have reported the use of estimated equations for energy expenditure when planning energy intake in critically ill children 41. Targeted IC to obtain accurate measurement of resting energy expenditure may allow individualized nutrition therapy in high-risk children in the PICU and prevent cumulative caloric imbalances 23.

(C) Nutrient Intake at the Bedside – Prescription and Delivery

Barriers to nutrition intake in critically ill children have been described across centers all over the world 34-36. Following accurate estimation of energy needs, the actual delivery of requisite nutrients may be challenging and requires a multidisciplinary effort. In the first week of the PICU course, children received less than 60% of their prescribed calories 44, 45. Caloric deprivation in the PICU is prevalent and its etiology is multifactorial 35, 46. In one study, less than half the children in the PICU received nutrition on the first day 44. Delay in initiation of nutrition, suboptimal use of parenteral nutrition and overall failure to prescribe adequate calories and protein were factors responsible for malnutrition during the PICU course of children in this study.

The PICU is a complex environment where routine interventions and procedures are in constant conflict with bedside nutrient delivery. Early institution of EN is associated with beneficial outcomes in animal models and human studies 47, 48, and has been increasingly implemented during critical illness, often using nutritional guidelines or protocols 49, 50. Despite its known benefits, EN is often delayed. Subsequent maintenance of enteral nutrient delivery remains elusive as EN is frequently interrupted in the intensive care setting for a variety of reasons, some of which are avoidable 35, 51. Frequent interruptions in enteral nutrient delivery may affect clinical outcomes secondary to caloric imbalance or reliance on PN 35. In order to realize the potential benefits of EN in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), both early initiation and maintenance of enteral feeds must be assured. We reviewed bedside EN delivery in 112 children in our PICU using a multidisciplinary bedside audit tool. Despite early initiation of EN, feeds were interrupted in many critically ill children admitted to our busy medical and surgical PICU 34. Avoidable EN interruptions were associated with more than 3-fold increase in the use of PN and a significant delay in reaching caloric goals. Fasting for procedures and intolerance to EN were the commonest reasons for prolonged EN interruptions. Interventions aimed at optimizing EN delivery must be designed after examining existing barriers to EN and directed at high-risk individuals who are most likely to benefit from these interventions. Infants, younger children and those requiring mechanical ventilation, were more likely to be fed via the post-pyloric route and had a longer stay in the PICU. Educational intervention and practice changes targeted at these high-risk patients may decrease the incidence of avoidable interruptions to EN in critically ill children.

Clinical practice guidelines, developed by multidisciplinary expert consensus and based on existing evidence may help improve nutrition support practices in the intensive care unit. The Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for nutrition support in critically ill adults provide a model for evidence based consensus-derived generation of practical recommendations, dissemination of recommendations and then systematic evaluation of their impact on patient outcomes. Adherence to these guidelines have been shown to increase EN intake, decrease hospital length of stay and a trend towards decreased mortality 52-55. Implementation of an institutional feeding protocol was associated with early institution of EN, shortened time to reaching caloric goal and decreased interruptions to established EN in a study conducted in PICU population 56. There are no randomized trials examining the effect of such protocols for feeding in the PICU, and their application remains sporadic with mixed effects 57, 58. Guidelines for enteral and parenteral nutrition for the critically ill child were recently revised by the guidelines committee and board of directors of the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) 33.

Nutritional Assessment during Critical Illness

The nutritional assessment of critically ill children may be challenging from both scientific and practical aspects. After admission, weights are infrequently obtained during the PICU course and acute changes in nutrition status may be missed or detected late 22. Failure to weigh children in the PICU is due to the perceived problems of moving critically ill patients and the low priority amongst healthcare workers for nutritional assessment. In a review of hospitalized adults outside the intensive care unit, weights on admission were obtained in less than half the patients 12. The overall lack of enthusiasm for weighing critically ill children results in failure to estimate the true incidence of malnutrition in this cohort. A weight-for-age Z score of -2.0 corresponds to a weight that is 2 standard deviations below the mean for a given age and sex. Z scores are preferred to percentiles when analyzing anthropometric data from populations with a high incidence of undernutrition 59. A weight-for-age Z score lower than -2.0, which is two standard deviations below the mean for age and sex, is termed as undernourished.

Anthropometric Assessment

Arm anthropometry (mid-upper arm circumference and triceps skinfold), body weights, lengths and body mass index (BMI) are commonly used to assess the nutritional status of these children. Hulst et al observed a correlation between energy deficits and deterioration in anthropometric parameters such as mid arm circumference and weight in a mixed population of critically ill children 11. The anthropometric abnormalities accrued during the PICU admission returned to normal by 6 months after discharge 7. Using reproducible anthropometric measures, Leite et al reported a 65% prevalence of malnutrition on admission with increased mortality in this group. 10 On follow up, a significant portion of children with protein energy malnutrition had further deterioration in nutritional status.

Body Composition

Emerging literature supports the concept that body composition is a primary determinant of health and a predictor of morbidity and mortality in children. Preservation and accrual of lean body mass during illness has been shown to be an important predictor for clinical outcomes in a variety of settings, including patients with sepsis, cystic fibrosis, and malnutrition 61-63. Although bedside anthropometric methods are inexpensive, they are sporadically applied in hospitalized children, may be insensitive in the setting of critical illness and limited by significant inter-observer variability. Weight changes and other anthropometric measurements in critically ill children should be interpreted in the context of edema, fluid therapy, volume overload and diuresis. In the presence of ascites or edema, ongoing loss of lean body mass may not be evident using weight monitoring. A variety of techniques of body composition measurement, including body densitometry by underwater weighing, neutron activation analysis, total body potassium determination or dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) have been described in the literature 64-67. Most of these methods are not practical for application in the clinical management of a critically ill child. DXA is a radiographic technique that can determine the composition and density of different body compartments (fat, lean tissue, fat free mass, and bone mineral content) and their distribution in the body. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) has been used extensively in pediatric practice for determining fat free mass, fat mass, lean mass and is recognized as a reference method for body composition research 68. Its results correlate well with direct chemical analyses, and there is good agreement between percentage body fat estimated by hydrodensitometry and by DXA 69. However, the application of DXA in the PICU is impractical. Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA), in contrast, is a bedside technique that can be applied to pediatric patients without exposure to radiation and with ease. Electrical current is conducted by body water, and impeded by other body components. BIA estimates the volumes of body compartments, including extracellular water (ECW), and total body water (TBW). TBW measures can be used to estimate lean body mass by applying age-appropriate hydration factors 69. BIA has not been validated in critically ill populations and hence its use outside clinical trials is not recommended in the PICU. The search for an ideal bedside body composition measurement technique in critically ill patient continues and some of these promising new methods require validation.

Biochemical Assessment

Nutritional assessment can also be achieved by measuring the visceral (or constitutive) protein pool, the acute-phase protein pool, nitrogen balance and resting energy expenditure. Albumin, which has a large pool and much longer half-life (14 – 20 days), is not indicative of the immediate nutrition status and may be skewed by changes in fluid status. Serum albumin concentrations may be affected by albumin infusion, dehydration, sepsis, trauma and liver disease, and independent of nutritional status. Thus, its reliability as a marker of visceral protein status is questionable. Pre-albumin, (also known as transthyretin or thyroxine binding prealbumin) is a stable circulating glycoprotein synthesized in the liver. It binds with retinol binding protein and is involved in the transport of thyroxine as well as retinol. Prealbumin, so named by its proximity to albumin on an electrophoretic strip, has a half-life of 24-48 hours and reflects more acute nutritional changes. Pre-albumin concentration is diminished in renal and liver disease. Prealbumin is readily measured in most hospitals and is a good marker for the visceral protein pool 70, 71. In children with burn injury, serum acute-phase protein levels rise within 12 to 24 hours of the stress, because of hepatic reprioritization of protein synthesis in response to injury 72. The rise is proportional to the severity of injury. Many hospitals are capable of measuring C-reactive protein (CRP) as an index of the acute-phase response. When measured serially (once a day during the acute response period), serum prealbumin and CRP are inversely related (i.e., serum prealbumin levels decrease and CRP levels increase with the magnitude proportional to injury severity and then return to normal as the acute injury response resolves). In infants after surgery, decreases in serum CRP values to less than 2 mg/dL have been associated with the return of anabolic metabolism and are followed by increases in serum prealbumin levels 73. Interleukin 6 (IL-6), a proinflammatory cytokine recognized as an early marker of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in several disease models, might be used to determine whether the inflammatory response is intact. Serum concentrations of IL-6 may be useful in identifying patients at risk of nutritional deterioration.

Micronutrient Deficiency in Critically Ill Children

The antioxidant properties of certain micronutrients have renewed interest in their role during critical illness. Vitamins C and E have important antioxidant properties. Selenium has also been shown to be a critical micronutrient with antioxidant functions in patients with thermal injury and trauma 74. A complex system of special enzymes, their co-factors (selenium, zinc, iron, manganese), sulfhydryl group donors (glutathione) and vitamins (E and C) form a defense system to counter the oxidant stress seen in the acute phase of injury or illness. Critically ill patients may have variable deficiencies of micronutrients in the early phase of illness. Vitamins and trace elements are redistributed from central circulation to tissues and organs during the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) 75, 76. Levels of trace elements such as iron, selenium and zinc, as well as water soluble vitamins are decreased, while copper and manganese levels may be increased 76, 77. In addition, trauma and burn patients are characterized by extensive losses of biologic fluids through wound exudates, drains, and hemorrhage, which cause negative micronutrient balances. The reduced stores of these enzyme cofactors, vitamins and trace elements decrease rapidly after injury and remain at subnormal levels for weeks. Low endogenous stores of antioxidants are associated with an increase in free radical generation, augmented systemic inflammatory response, cell injury, increased morbidity and mortality in the critically ill 78, 79. Recently, there is increased interest in the role of Vitamin D as an antioxidant. Serum levels of vitamin D are decreased in children with severe burns 80. Vitamin D status may be compromised for months after burn injury. The concept of early micronutrient supplementation to prevent the development of acute deficiency, to rectify the oxidant-antioxidant balance and reduce oxidative-mediated injuries to organs has driven recent trials in critically ill patients 81.

Antioxidant research in the critically ill has focused on copper, selenium, zinc, vitamins C, E and the vitamin B group 81. However, most of these studies were performed in relatively small patient populations presenting with nonhomogeneous diseases such as trauma, burns, sepsis, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and thus are underpowered to detect a treatment effect on clinically important outcomes. Heyland et al performed a systematic review of trials supplementing critically ill patients with antioxidants, trace elements, and vitamins with an aim to improve survival 74. The authors concluded that trace elements and vitamins that support antioxidant function, particularly high-dose parenteral selenium either alone or in combination with other antioxidants, are reportedly safe and may be associated with a reduction in mortality in critically ill patients.

Strategies For Prevention Of Malnutrition During Critical Illness

Acknowledge the prevalence of malnutrition in critically ill children

Nutrition support integrated into the critical care team

Nutritional assessment and evaluation of nutrition gals in all critically ill children

Use of a nutrition support algorithm to reach nutrition goals in the PICU

Examine institutional barriers to nutrition support and implement practice change

Assessment of nutritional adequacy and detection of nutritional deterioration with the help of regular anthropometric and biochemical assessments during the PICU course.

Prudent use of targeted IC

Early initiation and maintenance of EN.

Awareness of underfeeding, overfeeding and micronutrient deficiencies in critically ill children

Aim for individually tailored nutritional regimen and serial assessment during the course of critical illness.

Conclusion

Malnutrition is prevalent in children admitted to the PICU and their nutritional status may further deteriorate during the course of critical illness. Both macronutrient and micronutrient malnutrition have been described. Assessment of nutritional status on admission to the PICU will allow identification of those children at high risk of further nutritional deterioration. A basic understanding of the metabolic stress response and accurate assessment of energy expenditure are essential for designing individually tailored nutritional prescription for critically ill children. Both underfeeding and overfeeding are common in the PICU and have significant impact on outcomes from critical illness. Accurate measurement of energy expenditure, availability of nutrition support team, use of nutrition therapy guidelines and protocolized assessment of nutritional parameters at admission and regularly during PICU course are some steps to improve the nutritional state of children admitted to the PICU.

Contributor Information

Nilesh M. Mehta, Instructor, Harvard Medical School, Faculty in Division of Critical Care, Anesthesia, Children's Hospital, Boston MA 02115.

Christopher P. Duggan, Associate Professor of Pediatrics – Harvard Medical School, Director, Clinical Nutrition Service - Children's Hospital, Boston, Division of Gastroenterology/Nutrition, Children's Hospital, Boston MA 02115.

References

- 1.Butterworth CE., Jr Editorial: Malnutrition in the hospital. JAMA. 1974;230:879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bistrian BR, Blackburn GL, Vitale J, Cochran D, Naylor J. Prevalence of malnutrition in general medical patients. JAMA. 1976;235:1567–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merritt RJ, Suskind RM. Nutritional survey of hospitalized pediatric patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:1320–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.6.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chima CS, Barco K, Dewitt ML, Maeda M, Teran JC, Mullen KD. Relationship of nutritional status to length of stay, hospital costs, and discharge status of patients hospitalized in the medicine service. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:975–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00235-6. quiz 9-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:235–9. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(02)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Studley HO. Percentage of weight loss: a basic indicator of surgical risk in patients with chronic peptic ulcer. 1936 Nutr Hosp. 2001;16:141–3. discussion 0-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulst J, Joosten K, Zimmermann L, et al. Malnutrition in critically ill children: from admission to 6 months after discharge. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:223–32. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack MM, Wiley JS, Kanter R, Holbrook PR. Malnutrition in critically ill infants and children. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1982;6:20–4. doi: 10.1177/014860718200600120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack MM, Ruttimann UE, Wiley JS. Nutritional depletions in critically ill children: associations with physiologic instability and increased quantity of care. Jpen. 1985;9:309–13. doi: 10.1177/0148607185009003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leite HP, Isatugo MK, Sawaki L, Fisberg M. Anthropometric nutritional assessment of critically ill hospitalized children. Rev Paul Med. 1993;111:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulst JM, van Goudoever JB, Zimmermann LJ, et al. The effect of cumulative energy and protein deficiency on anthropometric parameters in a pediatric ICU population. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McWhirter JP, Pennington CR. Incidence and recognition of malnutrition in hospital. BMJ. 1994;308:945–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6934.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeejeebhoy KN. Nutritional assessment. Nutrition. 2000;16:585–90. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron JW, Rosenthal A, Olson AD. Malnutrition in hospitalized children with congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:1098–102. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170230052007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton JS, Hindmarsh PC, Scrimgeour CM, Rennie MJ, Preece MA. Energy expenditure in congenital heart disease. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:5–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forchielli ML, McColl R, Walker WA, Lo C. Children with congenital heart disease: a nutrition challenge. Nutr Rev. 1994;52:348–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norris MK, Hill CS. Nutritional issues in infants and children with congenital heart disease. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 1994;6:153–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz SM, Gewitz MH, See CC, et al. Enteral nutrition in infants with congenital heart disease and growth failure. Pediatrics. 1990;86:368–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart DW, Wolf SE, Mlcak R, et al. Persistence of muscle catabolism after severe burn. Surgery. 2000;128:312–9. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutan RL, Herndon DN. Growth delay in postburn pediatric patients. Arch Surg. 1990;125:392–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410150114021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Leavitt K, Duggan C. Cumulative Energy Imbalance in the PICU. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33 doi: 10.1177/0148607108325249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Leavitt K, Duggan C. Severe weight loss and hypermetabolic paroxysmal dysautonomia following hypoxic ischemic brain injury: the role of indirect calorimetry in the intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32:281–4. doi: 10.1177/0148607108316196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Leavitt K, Duggan C. Cumulative Energy Imbalance in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: Role of Targeted Indirect Calorimetry. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0148607108325249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askanazi J, Rosenbaum SH, Hyman AI, Silverberg PA, Milic-Emili J, Kinney JM. Respiratory changes induced by the large glucose loads of total parenteral nutrition. Jama. 1980;243:1444–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grohskopf LA, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL, Garrett DO, et al. A national point-prevalence survey of pediatric intensive care unit-acquired infections in the United States. J Pediatr. 2002;140:432–8. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.122499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW, Jr, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support: a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001;120:375S–95S. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.375s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta N, Jaksic T. The Critically Ill Child. In: Duggan W, Walker, editors. Nutrition in Pediatrics. 4 ed. Hamilton, Ontario: B. C. Decker Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Groof F, Joosten KF, Janssen JA, et al. Acute stress response in children with meningococcal sepsis: important differences in the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis between nonsurvivors and survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3118–24. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coss-Bu JA, Jefferson LS, Walding D, David Y, Smith EO, Klish WJ. Resting energy expenditure and nitrogen balance in critically ill pediatric patients on mechanical ventilation. Nutrition. 1998;14:649–52. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suman OE, Mlcak RP, Chinkes DL, Herndon DN. Resting energy expenditure in severely burned children: analysis of agreement between indirect calorimetry and prediction equations using the Bland-Altman method. Burns. 2006;32:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briassoulis G, Filippou O, Hatzi E, Papassotiriou I, Hatzis T. Early enteral administration of immunonutrition in critically ill children: results of a blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutrition. 2005;21:799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goran MI, Kaskoun M, Johnson R. Determinants of resting energy expenditure in young children. J Pediatr. 1994;125:362–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. Jpen. 2002;26:1SA–138SA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta NM, Hamilton S, McAleer D, et al. Challenges to enteral nutrient delivery in the critically ill child. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers EJ, Gilbertson HR, Heine RG, Henning R. Barriers to adequate nutrition in critically ill children. Nutrition. 2003;19:865–8. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adam SK, Webb AR. Attitudes to the delivery of enteral nutritional support to patients in British intensive care units. Clin Intensive Care. 1990;1:150–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Framson CM, LeLeiko NS, Dallal GE, Roubenoff R, Snelling LK, Dwyer JT. Energy expenditure in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:264–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000262802.81164.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardy CM, Dwyer J, Snelling LK, Dallal GE, Adelson JW. Pitfalls in predicting resting energy requirements in critically ill children: a comparison of predictive methods to indirect calorimetry. Nutr Clin Pract. 2002;17:182–9. doi: 10.1177/0115426502017003182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White MS, Shepherd RW, McEniery JA. Energy expenditure in 100 ventilated, critically ill children: improving the accuracy of predictive equations. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2307–12. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vazquez Martinez JL, Martinez-Romillo PD, Diez Sebastian J, Ruza Tarrio F. Predicted versus measured energy expenditure by continuous, online indirect calorimetry in ventilated, critically ill children during the early postinjury period. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102224.98095.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Kuip M, Oosterveld MJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, de Meer K, Lafeber HN, Gemke RJ. Nutritional support in 111 pediatric intensive care units: a European survey. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1807–13. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClave SA, Lowen CC, Kleber MJ, McConnell JW, Jung LY, Goldsmith LJ. Clinical use of the respiratory quotient obtained from indirect calorimetry. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:21–6. doi: 10.1177/014860710302700121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guenst JM, Nelson LD. Predictors of total parenteral nutrition-induced lipogenesis. Chest. 1994;105:553–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.2.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Neef M, Geukers VG, Dral A, Lindeboom R, Sauerwein HP, Bos AP. Nutritional goals, prescription and delivery in a pediatric intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor RM, Preedy VR, Baker AJ, Grimble G. Nutritional support in critically ill children. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:365–9. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hulst JM, Joosten KF, Tibboel D, van Goudoever JB. Causes and consequences of inadequate substrate supply to pediatric ICU patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:297–303. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000222115.91783.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore FA, Moore EE, Haenel JB. Clinical benefits of early post-injury enteral feeding. Clin Intensive Care. 1995;6:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamaoui E, Lefkowitz R, Olender L, et al. Enteral nutrition in the early postoperative period: a new semi-elemental formula versus total parenteral nutrition. Jpen. 1990;14:501–7. doi: 10.1177/0148607190014005501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore FA, Feliciano DV, Andrassy RJ, et al. Early enteral feeding, compared with parenteral, reduces postoperative septic complications. The results of a meta-analysis Ann Surg. 1992;216:172–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chellis MJ, Sanders SV, Webster H, Dean JM, Jackson D. Early enteral feeding in the pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1996;20:71–3. doi: 10.1177/014860719602000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adam S, Batson S. A study of problems associated with the delivery of enteral feed in critically ill patients in five ICUs in the UK. Intensive care medicine. 1997;23:261–6. doi: 10.1007/s001340050326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Day A, Jain M, Drover J. Validation of the Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients: results of a prospective observational study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2260–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145581.54571.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. Jpen. 2003;27:355–73. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027005355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain MK, Heyland D, Dhaliwal R, et al. Dissemination of the Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2362–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000234044.91893.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin CM, Doig GS, Heyland DK, Morrison T, Sibbald WJ. Multicentre, cluster-randomized clinical trial of algorithms for critical-care enteral and parenteral therapy (ACCEPT) CMAJ. 2004;170:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gurgueira GL, Leite HP, Taddei JA, de Carvalho WB. Outcomes in a pediatric intensive care unit before and after the implementation of a nutrition support team. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2005;29:176–85. doi: 10.1177/0148607105029003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambe C, Hubert P, Jouvet P, Cosnes J, Colomb V. A nutritional support team in the pediatric intensive care unit: changes and factors impeding appropriate nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petrillo-Albarano T, Pettignano R, Asfaw M, Easley K. Use of a feeding protocol to improve nutritional support through early, aggressive, enteral nutrition in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:340–4. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000225371.10446.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waterlow JC, Buzina R, Keller W, Lane JM, Nichaman MZ, Tanner JM. The presentation and use of height and weight data for comparing the nutritional status of groups of children under the age of 10 years. Bull World Health Organ. 1977;55:489–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelleher DK, Laussen P, Teixeira-Pinto A, Duggan C. Growth and correlates of nutritional status among infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) after stage 1 Norwood procedure. Nutrition. 2006;22:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brambilla P, Rolland-Cachera MF, Testolin C, et al. Lean mass of children in various nutritional states. Comparison between dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and anthropometry Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904:433–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sood M, Adams JE, Mughal MZ. Lean body mass in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:836. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.836-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Streat SJ, Beddoe AH, Hill GL. Aggressive nutritional support does not prevent protein loss despite fat gain in septic intensive care patients. J Trauma. 1987;27:262–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohn SH, Ellis KJ, Wallach S. In vivo neutron activation analysis. Clinical potential in body composition studies. Am J Med. 1974;57:683–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnson J, Dawson-Hughes B. Precision and stability of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements. Calcif Tissue Int. 1991;49:174–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02556113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krzywicki HJ, Ward GM, Rahman DP, Nelson RA, Consolazio CF. A comparison of methods for estimating human body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27:1380–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/27.12.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talso PJ, Miller CE, Carballo AJ, Vasquez I. Exchangeable potassium as a parameter of body composition. Metabolism. 1960;9:456–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elberg J, McDuffie JR, Sebring NG, et al. Comparison of methods to assess change in children's body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:64–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prior BM, Cureton KJ, Modlesky CM, et al. In vivo validation of whole body composition estimates from dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:623–30. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.2.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robinson MK, Trujillo EB, Mogensen KM, Rounds J, McManus K, Jacobs DO. Improving nutritional screening of hospitalized patients: the role of prealbumin. Jpen. 2003;27:389–95. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027006389. quiz 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Measurement of visceral protein status in assessing protein and energy malnutrition: standard of care. Prealbumin in Nutritional Care Consensus Group. Nutrition. 1995;11:169–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dickson PW, Bannister D, Schreiber G. Minor burns lead to major changes in synthesis rates of plasma proteins in the liver. The Journal of trauma. 1987;27:283–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Letton RW, Chwals WJ, Jamie A, Charles B. Early postoperative alterations in infant energy use increase the risk of overfeeding. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1995;30:988–92. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90327-5. discussion 92-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Suchner U, Berger MM. Antioxidant nutrients: a systematic review of trace elements and vitamins in the critically ill patient. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:327–37. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2522-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galloway P, McMillan DC, Sattar N. Effect of the inflammatory response on trace element and vitamin status. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37(Pt 3):289–97. doi: 10.1258/0004563001899429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maehira F, Luyo GA, Miyagi I, et al. Alterations of serum selenium concentrations in the acute phase of pathological conditions. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;316:137–46. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaetke LM, McClain CJ, Talwalkar RT, Shedlofsky SI. Effects of endotoxin on zinc metabolism in human volunteers. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E952–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.6.E952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goode HF, Cowley HC, Walker BE, Howdle PD, Webster NR. Decreased antioxidant status and increased lipid peroxidation in patients with septic shock and secondary organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:646–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199504000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Metnitz PG, Bartens C, Fischer M, Fridrich P, Steltzer H, Druml W. Antioxidant status in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:180–5. doi: 10.1007/s001340050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gottschlich MM, Mayes T, Khoury J, Warden GD. Hypovitaminosis D in acutely injured pediatric burn patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:931–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.020. quiz 1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berger MM. Antioxidant micronutrients in major trauma and burns: evidence and practice. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:438–49. doi: 10.1177/0115426506021005438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Calloway DH, Spector H. Nitrogen balance as related to caloric and protein intake in active young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1954;2:405–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/2.6.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, et al. Energy expenditure and caloric balance after burn: increased feeding leads to fat rather than lean mass accretion. Ann Surg. 2002;235:152–61. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shew SB, Keshen TH, Jahoor F, Jaksic T. The determinants of protein catabolism in neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1086–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90572-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McCowen KC, Friel C, Sternberg J, et al. Hypocaloric total parenteral nutrition: effectiveness in prevention of hyperglycemia and infectious complications--a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3606–11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patino JF, de Pimiento SE, Vergara A, Savino P, Rodriguez M, Escallon J. Hypocaloric support in the critically ill. World J Surg. 1999;23:553–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00012346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39(Suppl 1):5–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seale JL, Rumpler WV. Comparison of energy expenditure measurements by diet records, energy intake balance, doubly labeled water and room calorimetry. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:856–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Daly JM, Heymsfield SB, Head CA, et al. Human energy requirements: overestimation by widely used prediction equation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:1170–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.6.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hunter DC, Jaksic T, Lewis D, Benotti PN, Blackburn GL, Bistrian BR. Resting energy expenditure in the critically ill: estimations versus measurement. Br J Surg. 1988;75:875–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Klaus S, et al. World Health Organization equations have shortcomings for predicting resting energy expenditure in persons from a modern, affluent population: generation of a new reference standard from a retrospective analysis of a German database of resting energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1379–90. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elwyn DH, Kinney JM, Askanazi J. Energy expenditure in surgical patients. Surg Clin North Am. 1981;61:545–56. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tilden SJ, Watkins S, Tong TK, Jeevanandam M. Measured energy expenditure in pediatric intensive care patients. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:490–2. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150160120024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Phillips R, Ott L, Young B, Walsh J. Nutritional support and measured energy expenditure of the child and adolescent with head injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:846–51. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.6.0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chwals WJ, Bistrian BR. Predicted energy expenditure in critically ill children: problems associated with increased variability. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2655–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Coss-Bu JA, Klish WJ, Walding D, Stein F, Smith EO, Jefferson LS. Energy metabolism, nitrogen balance, and substrate utilization in critically ill children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:664–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferrannini E. The theoretical bases of indirect calorimetry: a review. Metabolism. 1988;37:287–301. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]