Abstract

Background

The value of American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification has been questioned. We evaluated the association of interventional cardiology (ICARD) certification with in-hospital outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in 2010.

Methods and Results

We identified physicians who performed ≥10 PCIs in 2010 in the CathPCI Registry and determined ICARD status using ABIM data. We compared in-hospital outcomes of patients treated by certified and non-certified physicians using hierarchical multivariable models adjusted for differences in patient characteristics and PCI volume. Primary endpoints were all-cause in-hospital mortality and bleeding complications. Secondary endpoints included emergency coronary artery bypass grafting, vascular complications, and a composite of any adverse outcome. With 510,708 PCI procedures performed by 5,175 physicians, case mix and unadjusted outcomes were similar among certified and non-certified physicians. The adjusted risks of in-hospital mortality (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02-1.19) and emergency CABG (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.12-1.56) were higher in the non-ICARD certified group, but the risks of bleeding, vascular complications, and the composite endpoint were not statistically significantly different between groups.

Conclusions

We did not observe a consistent association between ICARD certification and the outcomes of PCI procedures. Although there was a significantly higher risk of mortality and emergency CABG in patients treated by non-ICARD certified physicians, the risks of vascular complications and bleeding were similar. Our findings suggest that ICARD certification status alone is not a strong predictor of patient outcomes, and indicate a need to enhance the value of subspecialty certification.

Keywords: angioplasty, registry, revascularization, board certification

Introduction

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) was founded nearly 80 years ago in an effort to establish uniform standards for internists1. ABIM certification indicates “that internists have demonstrated – to their peers and to the public – that they have the clinical judgment, skills and attitudes essential for the delivery of excellent patient care.”1 Over time, ABIM certification has evolved to include both recertification and, more recently, maintenance of certification requirements2-3. Certification status plays a central role in many hospitals’ credentialing processes4, may influence patients’ choice of a physician5, and could be used to inform payment policies6. Although there is strong evidence for the internal validity of the testing process and the correlation of certification with other measures of physician quality such as program director’s ratings, the findings of studies examining the association of certification with patient outcomes have been mixed7-13.

Board certification is of particular interest in the field of interventional cardiology (ICARD) where it is a relatively new development. Certification was first offered in 1999 in an effort to standardize a rapidly expanding field14-15. Since then, there has been wide acceptance of the importance of ICARD certification. The current clinical competence statement for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) from the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions strongly recommends that physicians performing PCI hold active ICARD ABIM certification16. Nevertheless, although ICARD certification has been in place for 16 years, the association between ICARD certification and the outcomes of patients undergoing PCI has not been evaluated. Critically assessing the certification process is essential, as physicians have challenged the certification process in both the lay and research press, citing time and financial pressures as well as a perceived lack of value of the process17-19.

To address this gap in knowledge, we linked data regarding physician certification in ICARD from the ABIM database with patient outcomes data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s (NCDR) CathPCI Registry. Specifically, we examined the association of ABIM physician certification in ICARD with patterns of care and outcomes of patients undergoing PCI. It is important to emphasize, however, that this study addresses certification status of the performing physician at the time of the procedure, and not maintenance of certification or recertification.

Methods

Data Sources

The CathPCI Registry was established as a mechanism to promote quality improvement efforts at hospitals performing diagnostic and interventional cardiac procedures20. Hospitals voluntarily submit data to the registry using standardized definitions regarding patient demographics, medical history, risk factors, hospital presentation, initial cardiac status, procedural details, unique operator ID, medications, laboratory values and in-hospital outcomes of the PCI procedure. Data are entered by hospital personnel, and the data are only included in the analytic file if the hospital achieves >95% completeness of specified data elements. Currently, more than 1,600 sites submit data to the CathPCI Registry, which account for approximately 90% of catheterization labs performing PCI nationwide21-22. Previous data quality reviews have supported the accuracy of the data submitted to the CathPCI Registry23.

The ABIM database contains data on all physicians certified in internal medicine and each of its subspecialties. This includes demographic data, training dates, and certification status for internal medicine (IM), cardiovascular disease (CV), and ICARD.

Patient Population

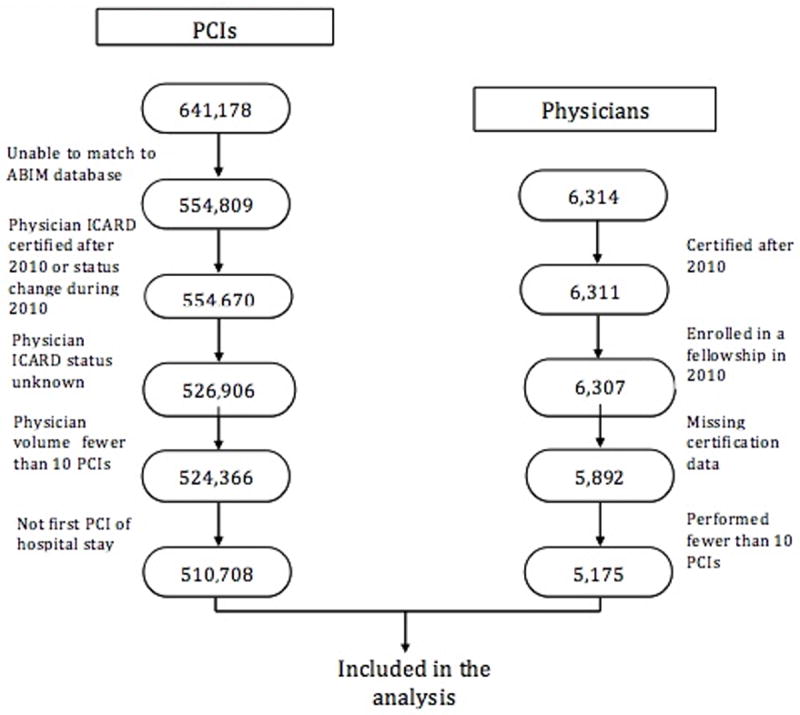

A flow chart of patient and physician selection is shown in Figure 1. All patients who underwent a PCI procedure reported to the CathPCI Registry performed between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010, were eligible to be included in the analysis, which included 641,178 PCIs. We excluded PCIs that could not be linked to a physician and patients who were younger than eighteen years of age at the time of the procedure. We considered only the first PCI performed during a hospitalization. After these exclusions were applied, a total of 510, 708 PCIs were linked to 5,175 associated physicians.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient and physician selection.

Physician Population

All physicians who performed at least 10 PCI procedures in 2010 as captured in the CathPCI Registry were eligible to be included in the analysis. We identified physicians in the CathPCI Registry using their National Provider Identifier (NPI) number. NPIs are voluntarily submitted by participating hospitals. There were 6,314 physicians with an NPI number recorded who performed a PCI in 2010. However, physicians were listed in the ABIM database using both NPI and unique physician identification numbers (UPINs). Accordingly, we used a NPI/UPIN crosswalk supplemented by manual searches to identify all physicians within the ABIM database. We excluded physicians who could not be linked with the ABIM data, had missing certification information in the ABIM database, or performed fewer than 10 PCIs in 2010. The final analysis included 5,175 physicians.

Physician Certification

For the primary analysis, physicians were divided into two groups: “certified” and “not certified” based on their ABIM ICARD certification status on January 1, 2010. In secondary analyses, we further stratified physicians by the year that they completed their CV fellowship training. We used CV fellowship as a marker across physician groups as it is a prerequisite for ICARD training. Those physicians who performed PCI prior to the formalization of ICARD training will not have interventional fellowship training dates recorded, but will have CV fellowship training dates available. Physicians who performed PCIs prior to the formation of accredited fellowship training programs were eligible for ICARD certification using the ABIM’s “practice pathway,” which required certification in CV and either a total of 500 lifetime PCIs or 150 PCIs in the previous two years. The first group included physicians who held ICARD certification in 2010 and had finished CV fellowship prior to 1999 (the first year of the ABIM ICARD certification; n = 2,200); the second group included physicians who held ICARD certification in 2010 and finished CV fellowship in 1999 or later (n = 1,466); the third group included physicians who had never held ICARD certification and who finished CV fellowship prior to 1999 (n = 1,044); the fourth group included physicians who never held ICARD certification and who finished CV fellowship in 1999 or later (n = 149); the fifth group included physicians who had previously held ICARD certification but whose certification had lapsed (n = 316).

Outcomes

The CathPCI Registry captures information about complications occurring during or following the PCI procedure up until hospital discharge22. Our two pre-specified primary endpoints were all-cause in-hospital mortality and bleeding complications. Bleeding complications consisted of suspected or confirmed bleeding events within 72 hours of the PCI associated with any of the following: a hemoglobin drop of ≥3 g/dl, transfusion of red blood cells, and/or an intervention at the bleeding site to reverse of stop the bleeding. Pre-specified secondary endpoints included need for emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), vascular complications requiring therapy (any access site occlusion, peripheral embolization, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, or AV fistula requiring intervention), and a composite endpoint of any outcome (death, bleeding, vascular complications, and emergency revascularization). These outcomes represent clinically significant, well-defined outcomes that have frequently been used in analyses of the CathPCI Registry.

Discharge Medications

In order to examine the association of ICARD certification with processes of care, we compared patterns of discharge medications- aspirin, statin therapy, and thienopyridines. We excluded patients with a contraindication to the medication. Furthermore, we excluded patients who did not undergo stent implantation from our assessment of thienopyridines.

Appropriate Use Criteria

In a secondary analysis, we examined differences in PCI procedural appropriateness as characterized by the 2012 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization (AUC)23. Procedures were characterized as either appropriate, of uncertain appropriateness, inappropriate, or unmappable24-25. Because prior analyses have shown that almost all acute PCIs were classified as appropriate26, we excluded patients undergoing PCI in the setting of an acute coronary syndrome from AUC analysis.

Analysis

We summarized physician and patient characteristics including physician demographics, certification attributes, and baseline patient characteristics. To assess the relationship between certification status and outcomes, we used methods appropriate for clustered data27-28. We used χ2 tests, adjusted for clustering by physician, to compare patient characteristics and outcomes across physician groups28. Then, to account for physician and patient characteristics, we estimated for each outcome a hierarchical generalized linear model with a logistic link function and a random intercept across physicians28. Each model was adjusted for physician PCI volume, years since their initial certification in cardiovascular medicine (as a proxy for years of experience), the PCI volume of the hospital where the physician performed most of his or her PCIs, as well as patient characteristics. Physician and hospital PCI volume were calculated using procedures performed in 2010. Physician volume was included as a dichotomous variable in the model (less than 50 procedures, and 50 or greater procedures). To account for the fact that some physicians perform procedures at more than one hospital, we performed automated and manual abstraction of CathPCI data to identify operators who performed cases at more than one hospital submitting data to the CathPCI Registry. We included the hospital at which the provider performed the majority of his or her procedures. We also included in each model patient risk factors previously shown to be significantly associated with our outcomes of interest (including death, bleeding, emergency CABG, and vascular complications). For each model we reported the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the effect of certification status (or, for the secondary outcomes, certification group) on the outcome. To improve the interpretation of multilevel model results we used recycled predictions to express effects as absolute differences in outcome rates; this method uses the model results to predict the outcome for all patients as if they were in each exposure group, and summarizes the differences29. In a secondary analysis, we included pairwise interaction terms between physician annual volume, hospital volume category, and ICARD status in the model. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp 2013, College Station TX). Analyses were approved by the Yale University School of Medicine’s Human Investigation Committee.

Results

Among the 6,314 eligible physicians, 717 were excluded because they performed fewer than 10 PCIs in 2010, 4 were excluded because they were enrolled in a fellowship program in 2010, 3 were excluded who received ICARD certification after 2010, and 415 had missing certification information. The remaining 5,175 interventional cardiologists performed a total of 510,708 PCI procedures between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010. The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1 based on certification status of the performing physician. Overall, patient characteristics were similar across the certification status groups. Of note, the ICARD certified group had a slightly higher proportion of patients with heart failure (11.8% vs 11.1%), ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (16.3% vs 15.5%), and acute coronary syndrome (70.2% vs 68.0%). The non-ICARD certified group had a higher proportion of patients with prior PCI (41.7% vs 40.3%), and patients undergoing elective PCI (48.9% vs 44.2%). Physician characteristics are shown in Table 2. Only 161 (3.2%) were female, and the mean age was 49.9 years. The mean age of noncertified physicians was 54.8 years compared with 48.0 in the certified group (P<0.001). A total of 3,666 (70.8%) held ICARD certification on January 1, 2010. ICARD certified physicians performed the majority of procedures (399,153 procedures; 78.2%). Among patients for whom information about practice type was available, a higher percentage of ICARD certified physicians practiced in an academic setting (7.8% vs 0.9%). On average, ICARD certified physicians performed more PCI in 2010 than non-ICARD certified physicians (111.8 PCI vs 75.8 PCI), and a higher proportion performed at least 50 PCI (77.6% vs 55.6, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Physician Certification

| Patient Characteristic | ICARD* certified, n (%) | Non-ICARD certified n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total PCI | 399,153 | 111,555 | |

| Age (years, mean (SD)) | 64.7 (12.1) | 64.8 (12.0) | 0.048 |

| Female | 129,966 (32.6) | 36,752 (32.9) | 0.114 |

| White | 354,014 (88.7) | 99,008 (88.8) | 0.965 |

| Black | 31,483 (7.9) | 8,686 (7.8) | 0.965 |

| Prior heart failure | 47,160 (11.8) | 12,332 (11.1) | 0.002 |

| Prior valve surgery | 5,723 (1.4) | 1,569 (1.4) | 0.585 |

| Prior CV† disease | 48,999 (12.3) | 13,227 (11.9) | 0.030 |

| Prior PCI‡ | 160,969 (40.3) | 46,526 (41.7) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 327,368 (82.0) | 91,047 (81.6) | 0.174 |

| Current hemodialysis | 9,347 (2.3) | 2,331 (2.1) | 0.002 |

| Chronic lung disease | 60,097 (15.1) | 17,257 (15.5) | 0.132 |

| Diabetes | 142,938 (35.8) | 40,136 (36.0) | 0.182 |

| STEMI§ | 65,128 (16.3) | 17,260 (15.5) | 0.026 |

| NSTEMI∥ | 185,517 (46.5) | 48,536 (43.5) | <0.001 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 280,277 (70.2) | 175,849 (68.0) | 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 7,628 (1.9) | 1,845 (1.7) | 0.001 |

| NYHA# class I/II | 16,167 (4.1) | 3,656 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 23,678 (5.9) | 5,187 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Pre-procedure TIMI flow | <0.001 | ||

| TIMI** -1 | 65,157 (16.3) | 17,678 (15.8) | |

| TIMI-2 | 31,872 (8.0) | 12,101 (10.8) | |

| TIMI-3 | 72,883 (18.3) | 23,676 (21.2) | |

| TIMI-4 | 227,190 (56.9) | 57,426 (51.5) | |

| Pre Procedure LVEF†† | 0.636 | ||

| < 30 | 16,518 (4.1) | 4,229 (3.8) | |

| 31 – 45 | 47,215 (11.8) | 12,693 (11.4) | |

| > 45 | 228,944 (57.4) | 65,048 (58.3) | |

| Missing | 106476 (36.7) | 29,686 (26.5) | |

| PCI Status | <0.001 | ||

| Elective | 176,542 (44.2) | 54,516 (48.9) | |

| Urgent | 151,753 (38.0) | 38,207 (34.2) | |

| Emergent | 69,330 (17.4) | 18,446 (16.5) | |

| Salvage | 1,292 (0.3) | 342 (0.3) | |

| Discharge prescriptions | |||

| Aspirin | 375,937 (94.2) | 103,527 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 343,705 (86.1) | 93,091 (83.4) | <0.001 |

| Thienopyridine | 351,137 (88.0) | 96,597 (86.6) | <0.001 |

interventional cardiology;

cardiovascular disease;

percutaneous coronary intervention;

ST segment elevation myocardial infarction;

non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction;

New York Heart Association;

thrombolysis in myocardial infarction;

left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 2.

Physician Characteristics (n = 5,175)

| Non-ICARD* certified | ICARD certified | Total | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Total # of Physicians | 1509 (29.2) | 3666 (70.8) | 5175 (100.0) | |

| Gender | 0.373 | |||

| Male | 1466 (97.2) | 3544 (96.7) | 5010 (96.8) | |

| Female | 43 (2.8) | 122 (3.3) | 165 (3.2) | |

| Type of Practice | <0.001 | |||

| Teaching | 14 (0.9) | 287 (7.8) | 301 (5.8) | |

| Solo or Group | 455 (30.2) | 1946 (53.1) | 2401 (46.4) | |

| HMO/Other | 29 (1.9) | 177 (4.8) | 206 (4.0) | |

| Hospital Practice | 99 (6.6) | 604 (16.5) | 703 (13.6) | |

| Missing | 912 (60.4) | 652 (17.8) | 1564 (30.2) | |

| Volume category | <0.001 | |||

| <50 | 670 (44.4) | 822 (22.4) | 1492 (28.8) | |

| 50+ | 839 (55.6) | 2844 (77.6) | 3683 (71.2) | |

| PCI volume | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (sd) | 75.8 (75.8) | 111.8 (85.3) | 101.3 (84.3) | |

| Certification Status | ||||

| Yes | 3,666 (70.8) | |||

| Yes, CV < 1999 | 2,200 (42.5) | |||

| Yes, CV ≥ 1999 | 1,466 (28.3) | |||

| No, CV < 1999 | 1,044 (20.2) | |||

| No, CV ≥ 1999 | 149 (2.9) | |||

| Lapsed | 316 (6.1) | |||

| Years since CV† fellowship‡ | <0.001 | |||

| 0-5yrs | 52 (3.4) | 555 (15.1) | 607 (11.7) | |

| 6-10yrs | 81 (5.4) | 762 (20.8) | 843 (16.3) | |

| 11-15yrs | 185 (12.2) | 730 (19.9) | 915 (17.7) | |

| 16-20yrs | 284 (18.8) | 578 (15.8) | 862 (16.7) | |

| 21-30yrs | 659 (43.7) | 897 (24.5) | 1556 (30.1) | |

| 30+yrs | 247 (16.4) | 144 (3.9) | 391 (7.6) | |

| Hospital PCI Volume | 0.016 | |||

| 1-199 | 129 (8.5) | 283 (7.7) | 412 (8.0) | |

| 200-399 | 286 (19.0) | 588 (16.0) | 874 (16.9) | |

| 400+ | 1094 (72.5) | 2795 (76.2) | 3889 (75.1) | |

| Age (yrs) on 1/1/2010 | <0.001 | |||

| mean (sd) | 54.8 (7.3) | 48.0 (8.0) | 49.9 (8.4) |

interventional cardiology;

cardiovascular disease;

years since end date of general cardiovascular disease fellowship.

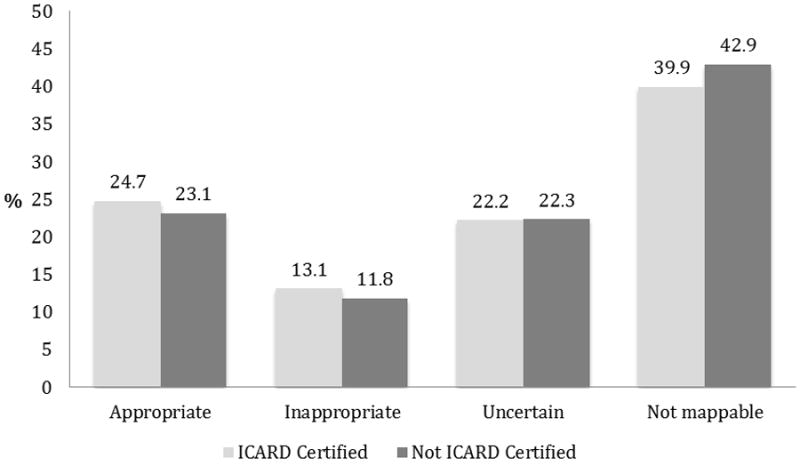

The proportions of patients discharged on aspirin, thienopyridines, and statins following the PCI procedure are also shown in Table 1. There were relatively small but statistically significant differences such that patients treated by certified physicians were more likely to be discharged on each medication. The proportions of appropriate procedures by certification status are shown in Figure 2. A higher proportion of PCIs performed by non-ICARD certified physicians were not mappable compared with PCIs performed by ICARD certified physicians (42.9% vs 39.9%, p=0.002). Among procedures that were mappable, higher proportions of PCI performed by ICARD certified physicians were classified as inappropriate (13.1% vs 11.8%, p=0.002) and appropriate (24.7% vs 23.1%, p=0.038). The proportions of procedures classified as uncertain were similar (22.2% vs 22.3%, p=0.934).

Figure 2.

Procedural Appropriateness of Non-acute PCI Stratified by Physician Certification.

In the secondary analysis that stratified physicians based on when they finished CV training, Table 2 shows that 20.2% of physicians had never been ICARD certified and finished CV fellowship prior to 1999. These physicians performed 14.2% (72,566 procedures) of all PCIs included in the analysis. A smaller proportion of PCIs (11,849 procedures; 2.3%) were performed by the 148 physicians (2.9%) who had never been ICARD certified and had finished CV fellowship in 1999 or later. Only 309 physicians (6.1%) had a lapsed certification during 2010, and these physicians performed 27,140 procedures (5.3% of the total number of procedures included in the analysis). There were modest differences in patient characteristics and discharge medications across these five physician categories.

Outcomes

Overall, the crude outcomes of patients treated by ICARD certified physicians were almost identical to those of non-ICARD certified physicians (Table 3). However, in multivariable analyses, the risks of both mortality and emergency CABG were statistically significantly higher for patients treated by non-ICARD board certified physicians (Table 4). As estimated by recycled predictions, this corresponded to absolute increases in mortality and emergency CABG of 0.08% and 0.03% respectively. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the adjusted risks of bleeding, vascular complications, and the composite endpoint of any adverse outcome. In a secondary analysis including interaction terms between physician annual volume category, hospital volume category, and ICARD status, only emergency CABG remained statistically significant.

Table 3.

Crude Outcomes of Primary and Secondary Analyses

| Outcome | Non-ICARD* n, (%) | ICARD n, (%) | ICARD, CV†<1999 n (%) | ICARD, CV≥1999 n (%) | Non-ICARD, CV<1999 n (%) | Non-ICARD, CV≥1999 n (%) | Lapsed n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111,555 (21.8) | 399,153 (78.2) | 242,452 (47.5) | 156,701 (30.7) | 72,566 (14.2) | 11,849 (2.3) | 27,140 (5.3) | |

| In-hospital death | 1,509 (1.4) | 5,436 (1.4) | 3,245 (1.3) | 2,191 (1.4) | 1,016 (1.4) | 173 (1.5) | 320 (1.2) |

| Bleeding | 1,878 (1.7) | 7,116 (1.8) | 4,321 (1.8) | 2,795 (1.8) | 1,232 (1.7) | 190 (1.6) | 456 (1.7) |

| Vascular complication | 475 (0.4) | 1,851 (0.5) | 1,084 (0.4) | 767 (0.5) | 296 (0.4) | 57 (0.5) | 122 (0.4) |

| Emergency CABG‡ | 255 (0.2) | 707 (0.2) | 405 (0.2) | 302 (0.2) | 174 (0.2) | 32 (0.3) | 49 (0.2) |

| Composite§ | 3,740 (3.4) | 13,659 (3.4) | 8,156 (3.4) | 5,503 (3.5) | 2,473 (3.4) | 408 (3.4) | 859 (3.2) |

interventional cardiology;

cardiovascular disease fellowship;

coronary artery bypass graft;

composite endpoint of any adverse event (including in-hospital death, bleeding, vascular complication, and emergency CABG).

Table 4.

Multivariable Outcomes of Primary and Secondary Analyses

| Outcome | ICARD* Certified | Non-ICARD (OR, 95% CI)§ | P-value | ICARD, CV†<1999∥ | ICARD, CV≥1999 (OR, 95% CI) | Non-ICARD, CV<1999 (OR, 95% CI) | Non-ICARD, CV≥1999 (OR, 95% CI) | Lapsed (OR, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital death | ref | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 0.018 | ref | 0.94 (0.78, 1.14) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) | 1.17 (0.90, 1.52) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) |

| Bleeding | ref | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 0.322 | ref | 0.88 (0.73, 1.07) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.04) | 0.77 (0.59, 1.02) | 0.96 (0.85, 1.13) |

| Vascular complication | ref | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) | 0.784 | ref | 0.90 (0.68, 1.18) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.08) | 0.87 (0.59, 1.29) | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33) |

| Emergency CABG‡ | ref | 1.32 (1.12, 1.56) | 0.001 | ref | 1.32 (0.91, 1.91) | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) | 1.86 (1.10, 3.09) | 0.97 (0.70, 1.34) |

| Composite endpoint | ref | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.276 | ref | 0.96 (0.84, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.07) |

interventional cardiology;

cardiovascular disease fellowship;

coronary artery bypass graft;

reference group is ICARD certified group in the primary analysis;

reference group is ICARD < 1999 certified group in the secondary analysis.

Findings were similar when we classified physicians into the five categories (Table 3). In multivariable analyses, the risk of death was significantly higher in patients treated by non-ICARD certified physicians who finished CV fellowship prior to 1999, and the risk of emergency CABG was significantly higher for patients treated by both non-ICARD certified groups (Table 4). Again there were no significant differences in the adjusted risks of bleeding, vascular complications, and the composite endpoint of any adverse outcome.

Discussion

In the United States in 2010, interventional cardiologists who did not hold ICARD certification performed a substantial proportion of PCI procedures. This included both physicians who had never been ICARD certified and those who had allowed their certification to lapse. We found that the care and outcomes of patients undergoing PCI procedures were generally similar regardless of the ICARD certification status of the performing physician. After adjusting for patient characteristics and PCI volume, the risks of mortality and emergency CABG were statistically higher among non-ICARD certified physicians compared with ICARD certified physicians. However, the overall event rates were low, and the clinical significance of these differences may be modest.

The requirements for obtaining certification in ICARD are rigorous. Given this rigor, it is notable that the majority of practicing interventional cardiologists have obtained ABIM ICARD certification. This is particularly striking among physicians who completed their CV training since ICARD certification was introduced in 1999. In this group, certification has become the norm, and only 2.9% were not certified in 2010. The reasons why physicians choose to become certified are probably multifactorial, but surveys of physicians suggest that both professional pride and hospital credentialing policies play major roles30. As noted, ABIM certification has been symbolic of professionalism in medicine, and has also been seen as indicative of a commitment to excellence and continued learning on the part of the physician.

In the present study, we did not observe a consistent association between ICARD certification and patient outcomes. Although patients treated by non-ICARD certified physicians were at statistically significantly higher risk of both mortality and emergency CABG, we did not see a similar association for the clinical endpoints of bleeding, vascular complications, and a composite of any adverse outcome. Furthermore, the clinical significance of the mortality and CABG findings is subject to interpretation. The adjusted absolute increase in mortality was 0.08%, which corresponds to 1 additional death for every 1250 patients. Similarly there was 1 additional emergency bypass surgery for every 3333 patients treated by non-certified physicians, when compared with certified physicians. Finally, a smaller proportion of non-acute PCI procedures performed by non-ICARD certified physicians were classified as inappropriate compared with procedures performed by ICARD certified physicians. Collectively, our findings suggest that ICARD certification status alone is not a strong predictor of the quality of care and in-hospital outcomes.

There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, PCI is a much safer and more reliable procedure today than in its early development. As prior studies have demonstrated, the introduction of coronary stents greatly improved procedural success and reduced the need for emergency CABG31-32. Similarly, increasing use of radial access and novel anticoagulant and antithrombotic strategies have likely reduced the risks of periprocedural bleeding and myocardial infarction33-34. In addition, there is increasing recognition that the outcomes of patients undergoing PCI are less attributable to an individual provider and more reflective of the totality of care delivered by the team treating the patient both during and after the PCI procedure35. Collectively, these factors may have had the effect of leveling the playing field, making it possible for interventional cardiologists with different training, knowledge, and technical expertise to achieve comparable results.

Second, the group of non-ICARD certified physicians is heterogeneous, consisting of physicians who did and did not complete an accredited fellowship in ICARD. In our analyses, we did not identify a significant interaction between physician training year and certification status, but we observed that the risks of mortality and emergency CABG were highest among physicians without ICARD certification who completed their CV training after 1999. Further research is warranted to determine whether the differences between ICARD certified and non-ICARD certified physicians will become more apparent over time.

Third, in spite of the rigor of the ABIM’s certification requirements, it is possible that the qualities and abilities currently captured by the certification process may not be the same as those needed to discriminate between physicians who perform PCI. For example, the certification exam can be used to assess an individual’s knowledge, but it cannot test for many of the qualities that are associated with highly skilled proceduralists, including the ability to make good decisions under extreme stress, superior manual dexterity, and quickly recognizing and effectively treating procedural complications. One promising approach to better assess this skillset could be the use of simulators, which could be folded into fellowship training and perhaps incorporated into the certification process36. Alternatively, there may be a role for direct observation of procedural skills by interventionalists specifically trained in observation and assessment of procedural skills37.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Our analysis examined only in-hospital outcomes, and it is possible that differences in the procedural quality may only become evident over longer periods of time or when considering other PCI-relevant outcomes including quality of life. We only considered patients who had a PCI, and could not assess whether certification status was associated with differences in the overall management of patients with acute and stable coronary artery disease. Nevertheless, the characteristics and measures of procedural appropriateness were similar across the two groups. The clinical endpoints that we examined are relatively infrequent in occurrence, and therefore may have made it difficult to find variation across operators. In addition, our study reflects the outcomes of patients undergoing PCI in 2010, and it is possible that the underlying associations between ICARD certification status and outcomes may be different in more recent data. However, studies using more recent CathPCI data show similar rates of complications38.

The ABIM identified 6,172 physicians who held ICARD certification in 2010, but we were unable to identify certification status for 16.2% (997) of these physicians in the linked dataset. This likely includes physicians who were practicing at non-NCDR hospitals and physicians for whom the NPI number was not available (as this was not a mandatory field on the NCDR data reporting sheet). Nevertheless, the case mix of physicians who could and could not be matched were comparable, suggesting that our findings are generalizable. Our study was also limited to hospitals that participate in the NCDR CathPCI Registry. The primary goal of the NCDR is to drive quality improvement through measurement and feedback and substantial research has demonstrated the power and importance of feedback for professional development39. It is possible that physician participation in NCDR-related activities may mitigate the association of certification with PCI outcomes. As noted, we assessed only ICARD certification at the time of the procedure, and did not evaluate whether or not participation or completion of the maintenance of certification program impacts PCI outcomes. Finally, the development of ICARD certification was a relatively recent event, and most if not all non-ICARD physicians participated in a training program even if it was not formally recognized. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to other specialties.

In conclusion, we found that the outcomes of patients undergoing PCI were excellent and varied modestly depending on the certification status of the performing physician. Our findings suggest there is an opportunity to enhance the value of subspecialty certification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This research was supported by both the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and by grant U01 HL105270-03 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. The views expressed in this manuscript represent those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCDR or its associated professional societies identified at CVQuality.ACC.org/NCDR. The NCDR had no role in the design or conduct of the study, the management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The manuscript was approved with only minor editorial changes by the CathPCI Registry Research and Publications Committee prior to manuscript submission. CathPCI Registry® is an initiative of the American College of Cardiology with partnering support from The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.

Footnotes

Dr. Curtis and Dr. Fiorilli had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Curtis and Dr. Fiorilli contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Mr. Herrin, Dr. Hess, Dr. Lipner and Dr. Holmboe contributed to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. Mr. Minges, Dr. Brennan, Dr. Messenger, Dr. Nallamothu, and Dr. Ting contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures: Dr. Fiorilli, Dr. Ting, Dr. Nallamothu, Dr. Brennan, Dr. Messenger, Mr. Minges and Dr. Herrin have no conflicts to report. Dr. Lipner is currently employed by ABIM. Drs. Hess and Holmboe were employed by ABIM when the study began. Dr. Hess is currently a consultant for ABIM and is co-inventor on a U.S. patent (No. 08452610) entitled “Method and system for determining a fair benchmark for physicians’ quality of patient care.” Dr. Holmboe receives royalties for a textbook from Mosby-Elsevier. Dr. Curtis receives salary support from the ACC NCDR to provide analytic services and with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to support development of quality measures. Dr. Curtis holds equity interest in Medtronic.

References

- 1.American Board of Internal Medicine. About ABIM. Available at: http://www.abim.org/about/default.aspx. Accessibility verified May 22nd, 2014.

- 2.Glassock RJ, Benson JA, Copeland RB, Godwin HA, Jr, Johanson WG, Jr, Point W, Popp RL, Scherr L, Stein JH, Taunton OD. Time limited certification and recertification: the program of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:59–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Benson JA, Jr, Webster GD. An analysis of the knowledge base of practicing internists as measured by the 1980 recertification examination. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:385–389. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-3-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freed GL, Dunham KM, Gebremariam A. Changes in hospitals’ credentialing requirements for board certification from 2005 to 2010. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:298–303. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Gallup Organization for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Awareness of and Attitudes Toward Board-Certification of Physicians. Princeton, NJ: The Gallup Organization; 2003. Available at: http://www.abim.org/pdf/publications/Gallup_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker GJ, Bosma JL, Burleson J, Borgstede JP. Introduction to value-based payment modifiers. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:718–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Meehan TP, Tate JP, Ho SY, Starkey KS, Lipner RS. Association between maintenance of certification examination scores and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1396–403. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norcini JJ, Kimball HR, Lipner RS. Certification and specialization: do they matter in the outcome of acute myocardial infarction? Acad Med. 2000;75:1193–1198. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200012000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Kimball HR. The certification status of generalist physicians and the mortality of their patients after acute myocardial infarction. Acad Med. 2001;76:S21–S23. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Kimball HR. Certifying examination performance and patient outcomes following acute myocardial infarction. Med Educ. 2002;36:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JP, Luebbert JJ, Wang Y, Rathore SS, Chen J, Heidenreich PA, Hammill SC, Lampert RI, Krumholz HM. Association of physician certification and outcomes among patients receiving an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. JAMA. 2009;301:1661–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp LK, Bashook PG, Lipsky MS, Horowitz SD, Miller SH. Specialty board certification and clinical outcomes: the missing link. Acad Med. 2002;77:534–542. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipner RS, Hess BK, Phillips RL., Jr Specialty board certification in the United States: issues and evidence. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2013 Fall;33(Suppl 1):S20–35. doi: 10.1002/chp.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Board of Internal Medicine. Certification in Interventional Cardiology (Brochure) Philadelphia, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Anonymous; 1998. Program Requirements for Residency Education in Interventional Cardiology. Available at: www.acgme.org/reqs/IM-IC998.HTM. Effective September, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harold JG, Bass TA, Bashore TM, Brindis RG, Brush JE, Jr, Burke JA, Dehmer GJ, Deychak YA, Jneid H, Jollis JG, Landzberg JS, Levine GN, McClurken JB, Messenger JC, Moussa ID, Muhlestein JB, Pomerantz RM, Sanborn TA, Sivaram CA, White CJ, Williams ES. ACCF/AHA/SCAI 2013 update on the clinical competence statement on coronary artery interventional procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:357–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centor RM, Fleming DA, Moyer DV. Maintenance of certification: beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:226–7. doi: 10.7326/M14-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinbrook R. Renewing board certification. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1994–1997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell YL. Interventional community pushes back against complex MOC program. TCTMD.com. Available at: http://www.tctmd.com/show.aspx?id=124117. Accessibility verified: May 22nd, 2014.

- 20.Brindis RG, Fitzgerald S, Anderson HV, Shaw RE, Weintraub WS, Williams JF. The American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR): building a national clinical data repository. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:2240–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. CathPCI: ACC’s Flagship Registry Leading Registry Innovation (Brochure) 2013 e-publication. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. CathPCI Registry data collection. Available at: http://ncdr.com/wedncdr/cathpci/home/datacollection. Accessibility verified May 5, 2014.

- 23.Messenger JC, Ho KKL, Young CH, Slattery LE, Draoui JC, Curtis JP, Dehmer GJ, Grover FL, Mirro MJ, Reynolds MR, Rokos IC, Spertus JA, Wang TY, Winston SA, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA NCDR Science and Quality Oversight Committee Data Quality Workgroup. The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) data quality brief. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American Heart Association, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography; Heart Failure Society of America; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Appropriateness criteria for coronary revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:530–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, Krone RJ, Dehmer GJ, Kennedy K, Nallamothu BK, Weaver WD, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Brindis RG, Spertus JA. Appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;306:53–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. Appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization focused update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donner A, Klar D. Cluster randomization trials in health services research. Arnold; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipner RS, Bylsma WH, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Tooker J, Cassel CK. Who is maintaining certification in internal medicine--and why? A national survey 10 years after initial certification. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:29–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moussa I, Reimers B, Moses J, Di Mario C, Di Francesco L, Ferraro M, Colombo A. Long-term angiographic and clinical outcome of patients undergoing multivessel coronary stenting. Circulation. 1997;96:3873–3879. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimmel SE, Localio AR, Krone RJ, Laskey WK. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:499–504. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang JS, Jin HY, Seo JS, Yang TH, Kim DK, Kim DK, Kim DI, Cho KI, Kim BH, Park YH, Je HG, Kim DS. The transradial versus the transfemoral approach for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:501–10. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I4A78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao SV, Ohman M. Anticoagulant therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.884478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis JP, Minges KE, Cherlin E, Elma MC, Bernheim SM, Messenger J, Ting HH, Berg D, Chen P. A qualitative study of the organizational strategies of high- and low-performing PCI hospitals: insights from TOP PCI. Circulation. 2013;128:A14758. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipner RS, Messenger JC, Kangilaski RW, Baim DS, Holmes DR, Jr, Williams DO, King SB., 3rd Can simulation technology be used to assess physicians’ technical proficiency in interventional cardiology? Simul Healthc. 2010;5:65–74. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181c75f8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, Oerline M, Carlin AM, Nunn AR, Dimick J, Banerjee M, Birkmeyer NJ Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1434–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronow HD, Gurm HS, Blankenship JC, Czeisler CA, Wang TY, McCoy LA, Neely ML, Spertus JA. Middle-of-the-night percutaneous coronary intervention and its association with percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes performed the following day: an analysis from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(1 Pt A):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boud D, Molloy E. Understanding it and doing it well. Routledge; Oxon, UK: 2013. Feedback in Higher and Professional Education. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.