Abstract

Background/Aims

We evaluated whether colonic transit time (CTT) can predict the degree of bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation undergoing scheduled colonoscopy in order to assist in the development of better bowel preparation strategies for these patients.

Methods

We analyzed the records of 160 patients with chronic constipation from March 2007 to November 2012. We enrolled patients who had undergone a CTT test followed by colonoscopy. We defined patients with a CTT ≥30 hours as the slow transit time (STT) group, and patients with a CTT <30 hours as the normal transit time (NTT) group. Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) scores were compared between the STT and NTT groups.

Results

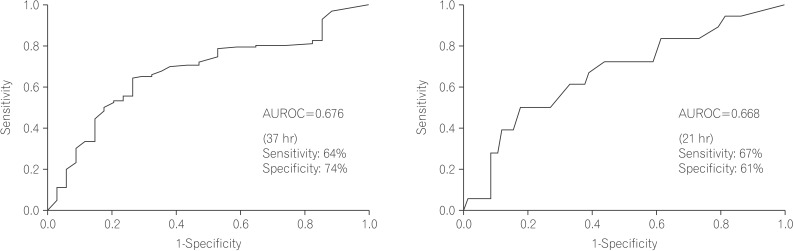

Of 160 patients with chronic constipation, 82 (51%) were included in the STT group and 78 (49%) were included in the NTT group. Patients with a BBPS score of <6 were more prevalent in the STT group than in the NTT group (31.7% vs. 10.3%, P=0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that slow CTT was an independent predictor of inadequate bowel preparation (odds ratio, 0.261; 95% confidence interval, 0.107-0.634; P=0.003). The best CTT cut-off value for predicting inadequate bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation was 37 hours, as determined by receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis (area under the ROC curve: 0.676, specificity: 0.735, sensitivity: 0.643).

Conclusions

Patients with chronic constipation and a CTT >30 hours were at risk for inadequate bowel preparation. CTT measured prior to colonoscopy could be useful for developing individualized strategies for bowel preparation in patients with slow CTT, as these patients are likely to have inadequate bowel preparation.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Bowel preparation, Colon transit time, Constipation

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, colonoscopy has been widely used and highlighted as a screening tool for colorectal cancer.1,2,3 Proper bowel preparation is an essential prerequisite for high-quality colonoscopy, because inadequate bowel preparation can result in difficulties during polypectomy. Inadequate bowel preparation can also lead to missed polyps, resulting in interval colorectal cancers.4 Moreover, inadequate bowel preparation causes difficulties with colonoscope insertion and increases complication rates.5,6,7

Factors known to be associated with inadequate bowel preparation include increased body weight, male sex, high BMI, age >60 years, previous abdominal surgery, liver cirrhosis, Parkinson's disease, underlying diseases (such as diabetes), and constipation.8,9,10,11 Bowel preparation can sometimes take longer in patients with chronic constipation than in those with normal bowel movement patterns.

The prevalence of chronic constipation has increased by 16.5% in Korea, Europe, and the United States. This is especially true in elderly patients, who represent a population who frequently undergo colonoscopies.12 A method of predicting the level of bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation leading to proper bowel preparation would be very useful for increasing the rates of successful colonoscopy. The factors affecting bowel preparation have been assessed in many studies.8,9,10,11 However, there are few reports of measurable or reproducible predictors of bowel preparation.11,13 In particular, there have been no studies on the prediction of bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation with a history of poor bowel preparation.

The colonic transit time (CTT) test, one of the basic methods of assessing the motor function of the large intestine, is widely used for patients with chronic constipation. This test can easily measure the transit time of each segment of the entire colon, provide objective information regarding abnormal bowel function, help in designing appropriate treatment plans, and determine disease classification based on the pathophysiology of chronic constipation.14,15 We hypothesize that deceased bowel movements could lead to less effective wash out of bowel preparation solution followed by inadequate bowel preparation. We conducted this study to assess if CTT measured prior to scheduled colonoscopy can predict the degree of bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation.

METHODS

This retrospective study was performed by reviewing the records of 160 patients who had visited Wonju Severance Christian Hospital from March 2007 to November 2012 for chronic constipation evaluations. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Wonju Severance Hospital. Chronic constipation was diagnosed according to the ROME II diagnostic criteria, and all patients underwent colonoscopy and a CTT test.16

1. CTT Measurement

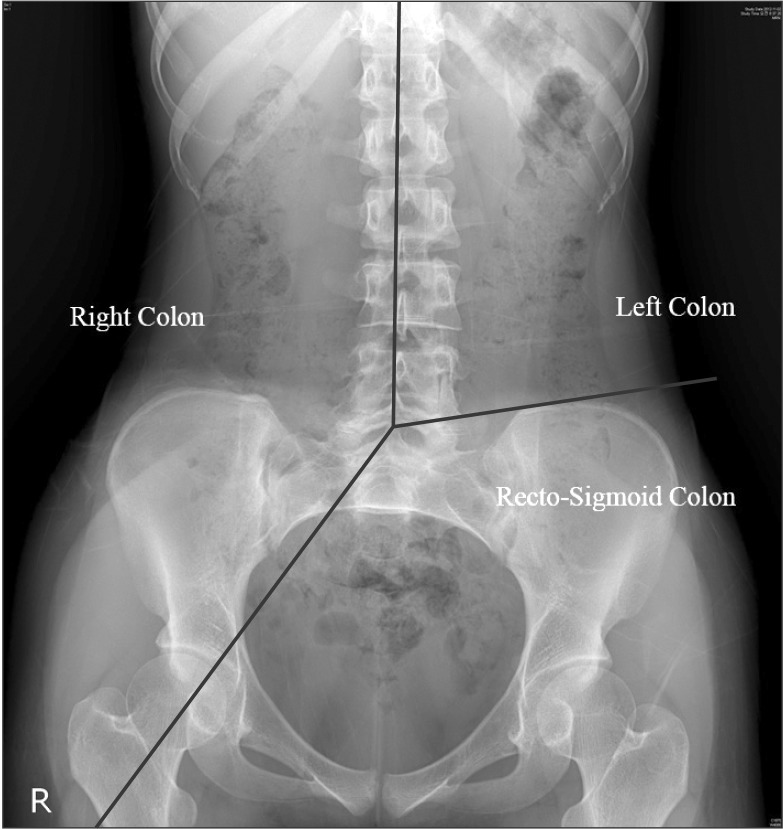

CTT was measured on days 4 and 7 using multiple radioopaque markers. Bowel preparation state was predicted by measuring markers on days 4 and 7. A single tablet of Kolomark™ (M. I. Tech, Pyeongtaek, Gyeonggi, Korea) containing 20 small rings was taken with water once per day for 3 days at 9 AM, and simple abdominal radiographs were taken at 9 AM on days 4 and 7. The right colon was identified on simple abdominal radiographs using two guidelines: one that connected all the spinous processes of the vertebrae and another that crossed from the 5th lumbar vertebral body to the right pelvic outlet. To identify the left colon, a line was drawn to connect all of the spinous processes, and the second line was drawn from the 5th lumbar vertebral body to the left anterior superior iliac spine. The portion of the colon within this plane was determined to be the left colon. A plane below these two lines, composed of a line that connected the right pelvic outlet and a second line that crossed the left anterior superior iliac spine, was determined to be the location of the rectum and sigmoid colon (Fig. 1).17 CTT was assessed by counting the number of radio-opaque markers on a plain radiogram on day 4. These numbers were multiplied by 1.2 and added to the number of radio-opaque markers counted on day 7.18 An average CTT has not been clearly determined for the Korean population, and previous studies have used various standards. However, recent studies have settled on a mean CTT of 30 hours.5,19,20

Fig. 1. Each segment of colonic transit time. Segments of colon were divided as right, left and rectosigmoid colon by black lines.

Based on the results of these studies, we classified patients with a CTT of >30 hours as the slow transit time (STT) group, and those with a CTT of <30 hours as the normal transit time (NTT) group. Furthermore, no standard transit time has been determined for cases of pelvic outlet obstruction, which delays passage through the sigmoid colon and rectum. Based on the mean CTT in each segment, we used 20 hours as the mean right and left CTT, and 10 hours as the mean transit time for the rectum and sigmoid colon. Slow transit constipation was diagnosed in people with a >20-hour delay in transit time in both right and left colons. Those with a transit time postponed by >10 hours in the rectum and sigmoid colon were defined as having pelvic outlet obstruction.

2. Bowel Preparation

All patients were instructed to avoid fiber-rich foods, fruits with seeds, and some grains for 3 days. They also took 4 L of PEG as a split dose: 2 L of solution in the evening before the procedure, and 2 L of solution the next morning at 8 am. Colonoscopies were performed within 5-7 hours after the end of bowel preparation. We enrolled patients who had finished their bowel preparation on schedule. To determine a bowel preparation scale without bias, all recorded colonoscopic images were reevaluated by one experienced physician (>5,000 colonoscopies). The medical record of each patient was also reviewed, and previous medical histories, previous colonoscopy reports, and pathologic findings were investigated.

The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) was used to evaluate the extent of bowel preparation. The scale splits the colon into three segments: the right, left, and transverse colons. Bowel preparation was measured on a scale from 0 to 3 in each segment. A part of the colon in which the mucosa cannot be observed on colonoscopy was given 0 points. When the mucosa could be clearly observed throughout the colon, the segment was given 3 points. Scores from each segment were added together, and the mean score was 6. Using a score of 6 as a reference, patients who received >6 points were classified as having proper bowel preparation, and patients who had <6 points in total or <2 points for one of any three segments were classified as having inadequate bowel preparation.20

3. Statistics

SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Demographics and medical histories were assessed using a descriptive statistics method. The frequencies and ratios of categorical variables were determined and analyzed using Pearson's chi-square or Fisher's exact test. The mean, minimal, and maximal values of continuous variables were described, and values were analyzed using Student's t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlations between BBPS and CTT. A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn to determine which BBPS scores could best predict bowel preparation quality.

RESULTS

1. Patient Characteristics

We analyzed a total of 160 patients with chronic constipation. There were 82 patients in the STT group (≥30-hour CTT), and 78 patients were classified in the NTT group (<30-hour CTT). Sixty-six percent of all patients were female, but no statistical differences in sex distributions (percentages of female patients) were observed between the two groups (STT vs. NTT, 63% vs. 69%; P=0.437). The mean patient age was 62±14 years. There were no differences in patient age between the two groups (STT vs. NTT, 64±15 years vs. 61±13 years; P=0.150). The proportions of patients with hypertension (STT vs. NTT, 27% vs. 33%; P=0.370) or diabetes (STT vs. NTT, 18% vs. 15%; P=0.623) determined from medical histories were not significantly different between the two groups. The proportions patients with neurovascular diseases including Parkinson's disease (STT vs. NTT, 10% vs. 4%; P=0.212), thyroid diseases including thyroid cancer (STT vs. NTT, 2% vs. 5%; P=0.434), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (STT vs. NTT, 5% vs. 1%; P=0.368), and history of abdominal surgery did not show any statistically significant differences between the two groups. Adenoma was identified in 32 patients (20%), but adenoma detection rate showed no significant difference between the two groups (STT vs. NTT, 21% vs. 19%; P=0.812). During colonoscopy, colon cancer was found in one patient from each group (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Colonoscopy-Related Data of Both Colonic Transit Time (CTT) Groups.

| Characteristic | Total | CTT ≥30 | CTT <30 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 160 | 82 | 78 | |

| Female gender, n (%) | 106 (66) | 52 (63) | 54 (69) | 0.437 |

| Age (yr, mean±SD) | 62±14 | 64±15 | 61±13 | 0.150 |

| Hypertension (%) | 30 | 27 | 33 | 0.370 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17 | 18 | 15 | 0.623 |

| Cerebral disease (%) | 7 | 10 | 4 | 0.212 |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0.434 |

| COPD (%) | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0.368 |

| Operation history (n) | 3 | 0 | 3 | n.c |

| Adenoma detection (%) | 20 | 21 | 19 | 0.812 |

| Cancerous lesion (n) | 1 | 1 | 0 | n.c |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; n.c., not comparable.

2. Comparison of CTT and BBPS

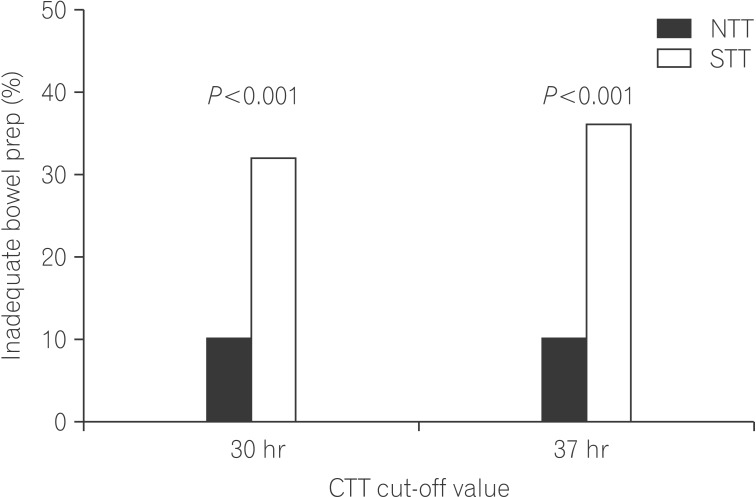

With reference values set to a mean CTT of 30 hours and a mean BBPS score of 6, the proportions of patients with a BBPS <6, reflecting inadequate bowel preparation, were 10.3% and 31.7% in the NTT and STT groups, respectively. The rate was 3-times higher in the STT group, and this difference was statistically significant (P=0.001) (Fig. 2). There was also a significant difference in the mean values of BBPS scores between the two groups (STT vs. NTT, 6.1±1.5 vs. 7.0±1.2; P<0.001). Although age, sex, history of diabetes, neurovascular diseases including Parkinson's, thyroid diseases, and CTT (reference, 30 hours) were found to be related to inadequate bowel preparation in other studies, this study showed that CTT was the only factor associated with inadequate bowel preparation(OR, 0.261; 95% CI, 0.107-0.634; P=0.003). Using ROC curve analysis, we found that a cut-off CTT of 37 hours could predict inadequate bowel preparation with 0.735 specificity and 0.643 sensitivity. This method was a more effective predictor of bowel preparation than CTT (area under the ROC curve: 0.676) (Fig. 2A). When the reference value for CTT was changed to 37 hours, the inadequate bowel preparation rates were 10.0% in the NTT group and 35.7% in the STT group, representing a larger difference (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Receiver operator characteristic graphs for the prediction of bowel preparation. A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) graph (A) showing the entire colon transit time (CTT), and a ROC graph (B) showing the left to right CTT for the prediction of inadequate bowel preparation. AUROC, Area under receiver operating characteristic.

Fig. 3. Based on the both cut-off values of 30 and 37 hours, proportions of inadequate bowel preparation were significantly higher in slow transit time (STT) than that in normal transit time (NTT). Cut-off values of colonic transit time (CTT) and inadequate bowel preparation.

3. Comparison Between the Groups and Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed in the STT group. Those with a >20-hour delay in the transit times of the right and left colons were classified as the slow transit constipation group, and those with a >10-hour delay in the rectum and sigmoid CTT were classified as the pelvic outlet obstruction group. The slow transit constipation group included 82 patients, while the pelvic outlet obstruction group contained 57 patients. The number of patients with both slow transit constipation and pelvic outlet obstruction was 46. Because most pelvic outlet obstruction patients had mixed-type constipation, 11 were diagnosed with pelvic outlet obstruction only. All patients were then further divided into three groups: group A (only slow CTT), group B (only pelvic outlet obstruction), and group C (mixed constipation types). When each group was compared with the NTT group, the relationship between CTT and inadequate bowel preparation revealed statistically significant differences for groups A and C, which included patients with slow transit constipation (group A vs. NTT group, 26.0% vs. 9.4%; P=0.027) (group C vs. NTT group, 30.4% vs. 9.4%; P=0.008). However, group B showed no statistically significant relationship between inadequate bowel preparation and CTT (group B vs. NTT group, 18.0% vs. 9.4%; P=0.593).

DISCUSSION

Inadequate bowel preparation decreases the effectiveness of colonoscopy due to difficulties in colonoscope insertion and retrieval, and by increasing the chances of missing small and large colorectal polyps.6,18,21 Additional testing due to inadequate bowel preparation leads to significantly increased national healthcare costs.21 Inadequate bowel preparation rates have been reported at between 20% and 30%, but this number may differ depending on the standards used.8,9,10,11,22 In the present study, inadequate bowel preparation was reported in 21.3% of cases, and this rate was similar to the results of previous studies.

Although previous studies have demonstrated factors causing inadequate bowel preparation, predicting the exact state of bowel preparation by these factors alone still has limitations. In particular, inadequate bowel preparation is frequently observed in patients with chronic constipation. However, there are no measurable and efficient tools to predict bowel preparation quality appropriately prior to colonoscopy.8 Hassan et al. reported that using a model incorporating a combination of factors, it is possible to predict the degree of bowel preparation with 60% sensitivity and 59% specificity.10 However, it is doubtful whether these factors could be uniformly applied to patients of all races and genders. Fatima et al. reported that it is possible to predict inadequate bowel preparation using a description of the patient's last stool, but this method depends entirely on the patient's personal description and may not be objective.13 Therefore, we tried to determine an accurate and objective method of predicting inadequate bowel preparation in patients with chronic constipation (those who are most likely to experience inadequate bowel preparation).

In this study, we focused on CTT as a predictor of inadequate bowel preparation in chronic constipation patients. Delayed CTT was shown to be the best predictor of inadequate bowel preparation in these patients. There is no standard reference CTT because this metric shows wide variations according to age, sex, ethnicity, and environment. In general, CTT is longer in women than in men, and in Western than in Eastern patient populations.5,19 Ina domestic study, the average CTT in healthy adults was found to be 20.5-30.3 hours.23

In this study, we used 30 hours as a reference to classify normal and delayed CTT. The sensitivity and specificity of using 30 hours as the standard for predicting inadequate bowel preparation were 74% and 56%. ROC curve analysis determined that the best specificity and sensitivity (74% and 64%, respectively) were obtained at 37 hours.

Patients with delayed CTT were divided into two groups: patients with delayed left to right movement within the colon (slow transit group),and patients with delayed transit in the recto-sigmoid colon (pelvic outlet obstruction group). Inadequate bowel preparation was significantly associated with the slow transit group, but was not related to the pelvic outlet group even though the test was performed in a small number of patients. This means that in patients with slow transit constipation, the main physiological characteristic of inadequate bowel preparation is slow CTT. It also shows that constipation due to pelvic outlet obstruction is not the cause of inadequate bowel preparation. In the case of patients with slow transit constipation, left to right CTT can predict inadequate bowel preparation, and showed the best specificity and sensitivity (61% and 67%) at 21 hours under ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2B).

Studies have shown that some drugs, such as magnesium hydroxide24 and bisacodyl, could be helpful for bowel preparation in patients with constipation, especially those with slow CTT.25,26 Therefore, we suggest that these medications could be helpful for bowel preparation in patients with slow CTT.

There are a number of limitations to the present study. The study was retrospective in design and included a relatively small number of patients (160). In addition, because of a lack of previous data, we did not include clinical data such as Bristol stool scale scores, frequency of bowel movements, and drug history, which may be important for predicating inadequate bowel preparation. Therefore, the relevant factors known to be associated with inadequate bowel preparation may not be properly reflected in our analysis, and it is possible that these known factors were not fully taken into account due to the small patient population. Furthermore, some bias may be present due to the patient selection method used. In this study, diagnosis of constipation was performed in accordance with the Rome II diagnostic criteria, but some data pertaining to the symptoms of IBS were missing. Therefore, it is possible that IBS was misdiagnosed as chronic constipation in some patients. For these reasons, future large-scale prospective studies are necessary to validate the results of this study, and to create a new model that can more accurately predict the degree of bowel preparation using CTT and several other factors.

In conclusion, despite the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, this study shows that CTT measurement in patients with chronic constipation is a good method of predicting the level of bowel preparation before colonoscopy. CTT measured prior to colonoscopy may be useful for developing individualized strategies for bowel preparation in patients with slow CTT who are likely to experience inadequate bowel preparation.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1220230).

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Walsh JM, Terdiman JP. Colorectal cancer screening: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289:1288–1296. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:169–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnand B, Bochud M, Froehlich F, Dubois RW, Vader JP, Gonvers JJ. 14. Appropriateness of colonoscopy: screening for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic individuals. Endoscopy. 1999;31:673–683. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha JM. Colonoscopy quality is the answer for the emerging issue of interval cancer. Intest Res. 2014;12:110–116. doi: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ell C, Fischbach W, Keller R, et al. A randomized, blinded, prospective trial to compare the safety and efficacy of three bowel-cleansing solutions for colonoscopy (HSG-01*) Endoscopy. 2003;35:300–304. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76–79. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Binderow SR, et al. Prospective, randomized, endoscopic-blinded trial comparing precolonoscopy bowel cleansing methods. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:689–696. doi: 10.1007/BF02054413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim WH, Cho YJ, Park JY, Min PK, Kang JK, Park IS. Factors affecting insertion time and patient discomfort during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:600–605. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, et al. Patient factors predictive of inadequate bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol: a prospective study in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:448–452. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181662442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jun DW, Park HY, Lee OY, et al. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Korean community: prevalence of functional constipation and self-reported constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1471–1477. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fatima H, Johnson CS, Rex DK. Patients' description of rectal effluent and quality of bowel preparation at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1244–1252.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho KO, Jo YJ, Song BK, Oh JW, Kim YS. Colon transit time according to physical activity and characteristics in South Korean adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:550–555. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meir R, Beglinger C, Dederding JP, et al. Age- and sex-specific standard values of colonic transit time in healthy subjects. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1992;122:940–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arhan P, Devroede G, Jehannin B, et al. Segmental colonic transit time. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:625–629. doi: 10.1007/BF02605761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung HK, Kim DY, Moon IH. Effects of gender and menstrual cycle on colonic transit time in healthy subjects. Korean J Intern Med. 2003;18:181–186. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2003.18.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang MS, Kim TO, Seo EH, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability between same-day picosulfate and split-dose polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for afternoon colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Intest Res. 2014;12:53–59. doi: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ER, Rhee PL. How to interpret a functional or motility test -colon transit study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:94–99. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin EK, Park SJ, Kim KJ, et al. Effect of combination pretreatment of polyethylene glycol solution and magnesium hydroxide for colonoscopy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:232–236. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delegge M, Kaplan R. Efficacy of bowel preparation with the use of a prepackaged, low fibre diet with a low sodium, magnesium citrate cathartic vs. a clear liquid diet with a standard sodium phosphate cathartic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1491–1495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verghese VJ, Ayub K, Qureshi W, Taupo T, Graham DY. Low-salt bowel cleansing preparation (LoSo Prep) as preparation for colonoscopy: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1327–1331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]