Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a leading cause of foodborne illnesses around the world. Since C. jejuni is microaerophilic and sensitive to oxygen, aerotolerance is important in the transmission of C. jejuni to humans via foods under aerobic conditions. In this study, 70 C. jejuni strains were isolated from retail raw chicken meats and were subject to multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis. In the aerotolerance testing by aerobic shaking at 200 rpm, 50 (71.4%) isolates survived after 12 h (i.e., aerotolerant), whereas 20 (28.6%) isolates did not (i.e., aerosensitive). Interestingly, further aerobic cultivation showed that 25 (35.7%) isolates still survived even after 24 h of vigorous aerobic shaking (i.e., hyper-aerotolerant). Compared to aerosensitive strains, the hyper-aerotolerant strains exhibited increased resistance to oxidative stress, both peroxide and superoxide. A mutation of ahpC in hyper-aerotolerant strains significantly impaired aerotolerance, indicating oxidative stress defense plays an important role in hyper-aerotolerance. The aerotolerant and hyper-aerotolerant strains were primarily classified into MLST clonal complexes (CCs)-21 and -45, which are known to be the major CCs implicated in human gastroenteritis. Compared to the aerosensitive strains, CC-21 was more dominant than CC-45 in aerotolerant and hyper-aerotolerant strains. The findings in this study revealed that hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni is highly prevalent in raw chicken meats. The enhanced aerotolerance in C. jejuni would impact human infection by increasing possibilities of the foodborne transmission of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions.

Keywords: Campylobacter jejuni, aerotolerance, chicken isolates, MLST-genotyping, oxidative stress

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the leading bacterial causes of gastroenteritis (Altekruse et al., 1999), annually causing approximately 400–500 million infection cases worldwide (Ruiz-Palacios, 2007). C. jejuni is a commensal bacterium in a wide range of animals and is zoonotically transmitted to humans mainly by the consumption of contaminated animal products (Nielsen et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2008). Particularly, high colonization levels of C. jejuni in the poultry intestines often result in the contamination of poultry products during processing, and contaminated poultry is the major source of transferring C. jejuni to humans (Silva et al., 2011). In Canada, 62% of retail raw chicken legs are contaminated with Campylobacter (Bohaychuk et al., 2006). In UK and US, similarly, Campylobacter is found in 76 and 57.3% of retail oultry products, respectively (Cui et al., 2005; Little et al., 2008). The transmission of Campylobacter is also caused by contamination through food handlers and cross-contamination involving contaminated kitchen equipment (Medeiros et al., 2008; Kennedy et al., 2011). Campylobacter is also isolated from various environmental sources, such as wildlife, sewage, and manure, which may work as vehicles to disseminate Campylobacter in food production systems and to humans (Whiley et al., 2013). In both foodborne and environmental routes of C. jejuni transmission to humans, C. jejuni should overcome harsh environmental conditions, particularly high oxygen tensions in atmosphere, which may directly impact the viability of C. jejuni.

As a thermotolerant and microaerophilic bacterium, C. jejuni grows optimally at 42°C under low oxygen environments (Young et al., 2007). Although C. jejuni is sensitive to high oxygen tensions in atmosphere, it exhibits a certain level of aerotolerance to survive under oxygen-rich conditions (Kaakoush et al., 2007; Luber and Bartelt, 2007). Aerotolerance is closely related to oxidative stress defense, since aerobic exposure results in the accumulation of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may give damage to proteins and lipids in C. jejuni (Oh et al., 2015). A few genes of oxidative stress defense have been shown to affect aerotolerance in C. jejuni. For instance, a mutation of fdxA encoding the ferredoxin FdxA significantly reduces aerotolerance in C. jejuni (van Vliet et al., 2001). A double mutation of bacterioferritin comigratory protein (i.e., Bcp) and thiol peroxidase (i.e., Tpx) impairs the aerotolerance of C. jejuni (Atack et al., 2008). Recently, we reported that alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) plays a more important role in the aerotolerance of C. jejuni than other key ROS-detoxification enzymes, such as catalase (KatA) and superoxide dismutase (SodB; Oh et al., 2015).

Presumably due to our traditional notion that C. jejuni is sensitive to oxygen, aerotolerance has not been investigated extensively in C. jejuni isolates from poultry. To examine the level of aerotolerance in C. jejuni, in the present study, we isolated 70 C. jejuni strains from retail chicken meats in Edmonton, Alberta, and analyzed their aerotolerance, revealing that aerotolerant and hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni strains are highly prevalent in chicken. Moreover, most hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni isolates belong to the clonal complexes (CCs) of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) that are frequently implicated in human infection and outbreaks.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of C. jejuni from Retail Chicken Meats

Chicken meats of different brands and products were purchased from seven different retail stores in Edmonton, Canada. C. jejuni was isolated as described by Chon et al. (2012) with some modifications. Briefly, the chicken meats were submerged in buffered peptone water (Oxoid, UK) at 37°C overnight and then inoculated in Bolton Campylobacter selective broth (Oxoid) at 42°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2). Aliquots (100 μl) were serially diluted and spread on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates supplemented with Preston Campylobacter selective supplements (Oxoid). Cultures were incubated at 42°C for 48 h under microaerobic conditions. C. jejuni colonies were confirmed by multiplex PCR as described previously (Wang et al., 2002). The primer sequences were described in Table 1. All C. jejuni strains were grown on MH media at 42°C under microaerobic conditions. Occasionally, culture media were supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Target gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni hipO | Jejuni_F Jejuni_R |

ACTTCTTTATTGCTTGCTGC GCCACAACAAGTAAAGAAGC |

Wanget al., 2002 |

| C. coli glyA | Coli_F Coli_R |

GTAAAACCAAAGCTTATCGTG TCCAGCAATGTGTGCAATG |

Wang et al., 2002 |

| C. lari glyA | Lari_F Lari_R |

TAGAGAGATAGCAAAAGAGA TACACATAATAATCCCACCC |

Wang et al., 2002 |

| aspA | aspA_F aspA_R |

AGTACTAATGATGCTTATCC ATTTCATCAATTTGTTCTTTGC |

Dingle et al., 2001 |

| glnA | glnA_F glnA_R |

TAGGAACTTGGCATCATATTACC TTGGACGAGCTTCTACTGGC |

Dingleet al., 2001 |

| gltA | gltA_F gltA_R |

GGGCTTGACTTCTACAGCTACTTG CCAAATAAAGTTGTCTTGGACGG |

Dingle et al., 2001 |

| glyA | gly_F gly_R |

GAGTTAGAGCGTCAATGTGAAGG AAACCTCTGGCAGTAAGGGC |

Dingleet al., 2001 |

| tkt | tkt_F tkt_R |

GCAAACTCAGGACACCCAGG AAAGCATTGTTAATGGCTGC |

Dingle et al., 2001 |

| pgm | pgm_F pgm_R |

TACTAATAATATCTTAGTAGG CACAACATTTTTCATTTCTTTTTC |

Dingle et al., 2001 |

| uncA | uncA_F uncA_R |

ATGGACTTAAGAATATTATGGC ATAAATTCCATCTTCAAATTCC |

Dingle et al., 2001 |

| ahpC | mahpC-F mahpC-R |

CATGATAGTTACTAAAAAAGCTTTAG GTTAAAGTTTAGCTTCGTTTTTGCC |

Oh and Jeon, 2014 |

MLST Analysis

MLST analysis of C. jejuni isolates was performed based on the method outlined in pubMLST (pubmlst.org) and a previous report (Dingle et al., 2001) by using seven housekeeping genes, including aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt, and uncA (Table 1). Overnight culture of C. jejuni on MH agar plates was harvested in 1 ml of PBS, and then 10 μl of C. jejuni suspension was mixed with 90 μl of PBS and boiled for 10 min. After centrifugation, pellets were removed, and supernatant was used as template. PCR was carried out with ExTaq polymerase (Takara, Japan). PCR amplicons were commercially sequenced by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea), and the sequences were analyzed in the Campylobacter PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/).

Aerotolerance Test

Aerotolerance test was carried out according to our previous report (Oh et al., 2015). Briefly, C. jejuni strains were grown on MH agar at 42°C for 18 h under microaerobic conditions. C. jejuni strains were resuspended in fresh MH broth and diluted to an OD600 of 0.07, and then bacterial suspensions were incubated at 42°C with shaking at 200 rpm under aerobic conditions. Samples were taken after 0, 12, and 24 h for serial dilution and CFU counting.

Susceptibility to Oxidative Stress

Campylobacter jejuni strains were inoculated in MH broth at 42°C for 8 h with agitation under microaerobic conditions, and then bacterial cultures were exposed for 1 h to oxidants, including 100 μM of cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), 1 mM of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 100 μM menadione (MND; a superoxide generator). The viability was determined by serial dilution and CFU counting.

Construction of ahpC Mutants

A suicide plasmid for an ahpC mutation in C. jejuni was described in our previous study (Oh and Jeon, 2014). The ahpC suicide vector was introduced to C. jejuni strains by electroporation, and ahpC mutants were selected by growing on MH agar supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml). The ahpC mutation was also confirmed by PCR with mahpC-F and mahpC-R primers (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, inc., USA). Statistical significance of differences between the groups was compared by using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The frequency distribution was determined as described elsewhere (Callicott et al., 2008) by performing the Mann–Whitney test followed by one-way ANOVA. n.s.: P > 0.5, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Results

MLST Analysis of C. jejuni Isolates from Retail Chicken Meats

We isolated 70 C. jejuni strains from 19 raw chicken meats from seven different retail stores in Edmonton, Alberta. The majority (77.1%) of C. jejuni strains was isolated from whole chicken samples, and 18.6% from drumsticks, and 4.3% from thighs (Table 2). The MLST results showed that the 70 strains were distributed in six different CCs. The major CCs were 21 and 45 that constituted 42.86 and 21.43% of C. jejuni isolates from chickens, respectively (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 2.

Clonal complexes of C. jejuni isolates from raw chicken meats.

| Clonal complex | ST no. | Isolate number | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 13 | 66 | Whole chicken |

| 21 | 23 | Whole chicken | |

| 24 | Whole chicken | ||

| 32 | Whole chicken | ||

| 33 | Whole chicken | ||

| 34 | Whole chicken | ||

| 36 | Whole chicken | ||

| 37 | Whole chicken | ||

| 43 | 29 | Thigh | |

| 44 | Whole chicken | ||

| 50 | 25 | Whole chicken | |

| 30 | Whole chicken | ||

| 31 | Whole chicken | ||

| 35 | Whole chicken | ||

| 38 | Whole chicken | ||

| 806 | 62 | Whole chicken | |

| 63 | Whole chicken | ||

| 64 | Whole chicken | ||

| 65 | Whole chicken | ||

| 1086 | 8 | Whole chicken | |

| 43 | Whole chicken | ||

| 2375 | 13 | Whole chicken | |

| 2377 | 68 | Drumstick | |

| 3794 | 10 | Whole chicken | |

| 4663 | 15 | Drumstick | |

| 16 | Drumstick | ||

| 4681 | 11 | Whole chicken | |

| 12 | Whole chicken | ||

| 4911 | 67 | Whole chicken | |

| 6261 | 7 | Whole chicken | |

| UAa | 1698 | 48 | Drumstick |

| 49 | Drumstick | ||

| 50 | Drumstick | ||

| 69 | Drumstick | ||

| 70 | Drumstick | ||

| 934 | 54 | Whole chicken | |

| 158 | 28 | Drumstick | |

| 1352 | 55 | Thigh | |

| 45 | 45 | 52 | Whole chicken |

| 53 | Whole chicken | ||

| 56 | Whole chicken | ||

| 57 | Whole chicken | ||

| 58 | Whole chicken | ||

| 137 | 2 | Whole chicken | |

| 4 | Whole chicken | ||

| 659 | 1 | Whole chicken | |

| 998 | 27 | Drumstick | |

| 1818 | 21 | Whole chicken | |

| 22 | Whole chicken | ||

| 6193 | 26 | Drumstick | |

| 59 | Whole chicken | ||

| 60 | Whole chicken | ||

| 61 | Whole chicken | ||

| 362 | 587 | 3 | Whole chicken |

| 14 | Whole chicken | ||

| 39 | Whole chicken | ||

| 40 | Whole chicken | ||

| 41 | Whole chicken | ||

| 42 | Whole chicken | ||

| 353 | 452 | 6 | Whole chicken |

| 9 | Whole chicken | ||

| 3484 | 45 | Whole chicken | |

| 354 | 2359 | 5 | Whole chicken |

| 48 | 142 | 51 | Thigh |

| NTb | 17 | Whole chicken | |

| 18 | Whole chicken | ||

| 19 | Whole chicken | ||

| 20 | Whole chicken | ||

| 46 | Drumstick | ||

| 47 | Drumstick |

aUA: isolates that were unassigned to any CC defined.

bNT: not typable.

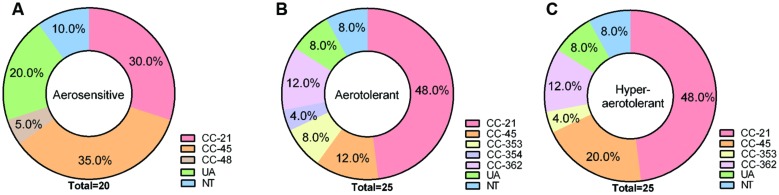

Differential Aerotolerance Levels in C. jejuni Chicken Isolates

The aerotolerance of the 70 C. jejuni isolates from chickens was investigated by growing them aerobically with vigorous shaking at 200 rpm. Depending on the levels of aerotolerance, the 70 isolates were clustered into three groups: (i) the aerosensitive group that lost viability before 12 h (Figure 1A), (ii) the aerotolerant group in which C. jejuni strains maintained viability for 12∼24 h (Figure 1B), and (iii) the hyper-aerotolerant group where C. jejuni strains remained viable even after 24 h of aerobic shaking (Figure 1C). Whereas a total of 20 strains were aerosensitive, most isolates were aerotolerant or hyper-aerotolerant (Figure 1). Interestingly, 25 C. jejuni strains were hyper-aerotolerant and maintained viability even after 24 h of vigorous shaking (at 200 rpm) under aerobic conditions (Figure 2C). The major CCs were CC-45 (35%) and CC-21 (30%) in the aerosensitive group (Figure 2A). However, CC-21 was predominant in both aerotolerant and hyper-aerotolerant groups; 48% in each (Figures 2B,C). No C. jejuni isolates in CC-353 and CC-362 were aerosensitive, but they constituted about 16% of hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni isolates (Figures 2A,C). These data show high prevalence of hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni in retail chicken meats, which clusters mainly in a few major CCs.

FIGURE 1.

The aerotolerance levels of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from raw chicken meats. (A) Aerosensitive strains lost the viability prior to 12 h of aerobic shaking. (B) Aerotolerant strains maintained viability 12∼24 h of aerobic shaking. (C) Hyper-aerotolerant strains remained viable after 24 h of aerobic ∼shaking at 200 rpm. The results show the means and standard deviations of three different experiments. The aerotolerance tests were repeated at least three times, and similar results were observed in all the experiments.

FIGURE 2.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) clonal complexes of C. jejuni isolates in three different aerotolerance groups; (A) aerosensitive, (B) aerotolerant, (C) hyper-aerotolerant groups.

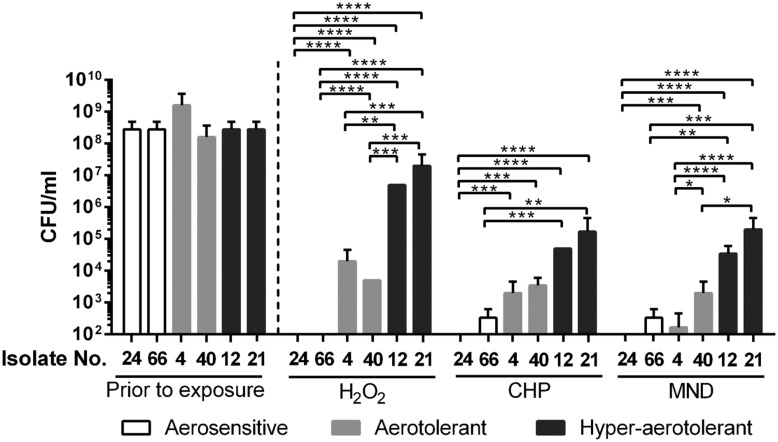

Oxidative Stress Resistance in C. jejuni Isolates

Since oxidative stress defense plays an important role in the aerotolerance of C. jejuni (Oh et al., 2015), oxidative stress resistance was compared between the different aerotolerance groups. Two strains from each aerotolerance group were randomly chosen and exposed to different kinds of oxidants for 1 h for viability testing. The strains from the aerosensitive group easily lost viability by exposure to H2O2, CHP, and menadione (Figure 3). However, two strains from the hyper-aerotolerance group demonstrated significantly enhanced resistance to oxidative stress, both peroxide and superoxide (Figure 3). The strains from the aerotolerant group were more resistant to oxidants than the strains from the aerosensitive group but more susceptible than those from the hyper-aerotolerant group (Figure 3). The results clearly indicate that hyper-aerotolerant strains are more resistant to oxidative stress than aerosensitive strains.

FIGURE 3.

Oxidative stress resistance of C. jejuni isolates from different aerotolerance groups. The results show the CFU levels after 1 h exposure to oxidants, including 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), 100 μM cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), and 100 μM menadione (MND). Statistical significance was analyzed with two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, inc.). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

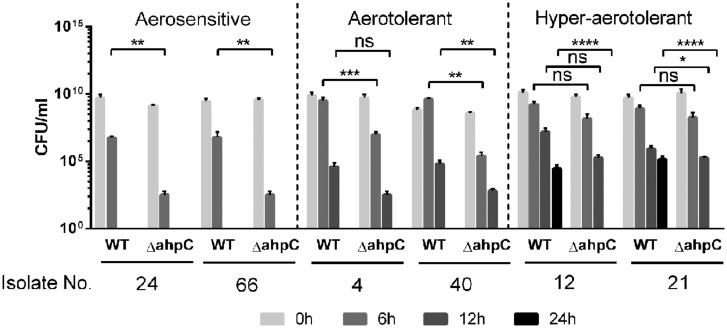

Role of ahpC in the Aerotolerance of Hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni Isolates

Our previous study showed that ahpC plays a key role in C. jejuni survival under aerobic conditions, compared to other ROS-detoxification genes, such as katA and sodB (Oh et al., 2015); thus, we decided to investigate how ahpC contributes to hyper-aerotolerance in C. jejuni. We constructed ahpC knockout mutants of the six C. jejuni strains from the three different aerotolerance groups. The ahpC mutation in the strains from the aerosensitive group resulted in approximately 3 log CFU reduction compared to wild type after 6 h of aerobic culture (Figure 4). Interestingly, ahpC mutants of the hyper-aerotolerant strains did not survive after 24 h, indicating the ahpC mutation reduced the aerotolerance level from hyper-aerotolerance to aerotolerance. These findings clearly showed that oxidative stress defense, particularly ahpC, is critical for the hyper-aerotolerance in C. jejuni.

FIGURE 4.

Growth defects in the ahpC mutants under aerobic conditions. The results show the CFU levels of triplicate samples after 6, 12, and 24 h culture under aerobic conditions with shaking at 200 rpm. The strains were selected from the three different aerotolerance groups. The experiment was repeated at least three times, and similar ∼results were ∼observed in all experiments. Statistical significance was determined with two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, inc.). n.s.: P > 0.5, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Discussion

The poultry intestines provide optimal growth conditions for C. jejuni, such as high body temperature (42°C), high nutrients, and low oxygen levels. However, C. jejuni is exposed to oxygen-rich conditions during food processing and preservation. Thus, oxidative stress is an unavoidable stress that C. jejuni should overcome to survive during its foodborne transmission to humans (Kim et al., 2015). Despite our common perception that C. jejuni is sensitive to oxygen, in this study, we revealed that hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni is highly prevalent in raw chicken meats. Arcobacter sp. are similar to Campylobacter and previously described as an aerotolerant Camplyobacter-like organism. Arcobacter is associated with animals and humans, and is frequently isolated in poultry (Vandamme et al., 1992; Snelling et al., 2006). Therefore, specific identification methods are needed to differentiate between Campylobacter and Arcobacter (Call et al., 2003), and multiplex PCR is often used for this purpose (Mandrell and Wachtelt, 1999). The hipO gene encoding hipuricase is present only in C. jejuni but not in any other Campylobacter sp. and Arcobacter sp. (Wang et al., 2002; Jensen et al., 2005). Whereas C. jejuni preferably grows at 42°C, Arcobacter grows optimally 24∼30°C (Phillips, 2001). In this study, C. jejuni was isolated at 42°C, at which Arcobacter cannot grow (Bhunia, 2008). In addition, the isolates were confirmed by PCR with primers for the hipO gene and classified by the MLST scheme for C. jejuni.

Most C. jejuni isolates from raw chicken meats belonged to CC-21 (42%) and CC-45 (21%; Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). This is consistent with previous reports from Canada and other countries. The ST-21 and ST-45 complexes are most dominant in a variety of sources around the world, accounting for 39 and 14% C. jejuni isolates deposited in pubMLST, where 76% of isolates in the CC ST-21 and 60% in the CC ST-45 are of human origin, such as stool and blood (Colles and Maiden, 2012). In the UK, CCs ST-21 and ST-45 are commonly detected in veterinary (i.e., cow, pet, sheep, and poultry) and human sources (Manning et al., 2003). CCs 21, 45, 353, and 354 are also highly prevalent in sources from humans and foods in Eastern China (Zhang et al., 2015). According to the results of an MLST analysis of 122 C. jejuni isolates from Danish patients with symptoms of gaostroenteritis, reactive arithritis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome, CCs ST-21, -45, and -22 are highly prevalent, accounting for 64% of all C. jejuni isolates from humans. Whereas ST-22 is significantly linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome, ST-21 and -45 are primarily associated with gastroenteritis (Nielsen et al., 2010). An extensive MLST analysis of 289 C. jejuni isolates in Canada showed that CCs 21, 45, and 353 constitute the major C. jejuni population (CC-21: 26%, CC-45: 18%, and CC-353: 11%) in a variety of sources, including humans, chickens, raw milk, and environmental water. Interestingly, more than 50% of isolates that were classified in CC-21 were from humans (Lévesque et al., 2008), indicating high frequencies of human infection by C. jejuni strains in CC-21. In the US, an MLST analysis of 47 C. jejuni isolates from 12 outbreaks exhibited that CC ST-21 is commonly involved in human epidemics (Sails et al., 2003). Whereas CC-21 and CC-45 were distributed at similar levels in the aerosensitive C. jejuni isolates (CC-21: 30%, CC-45: 35%; Figure 2A), CC-21 is predominant in both aerotolerant (48%) and hyper-aerotolerant (48%) isolates (Figures 2B,C), and the frequencies of CC-21 distribution in aerotolerant and hyper-aerotolerant groups were statistically significant (Supplementary Figure S2).

Hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni strains were more resistant to peroxide (i.e., H2O2 and CHP) and superoxide (i.e., menadione) stresses than aerosensitive strains (Figure 3), suggesting that increased resistance to oxidative stress would contribute to hyper-aerotolerance in C. jejuni. Our previous study showed that ahpC is the most important ROS-detoxification gene in the aerotolerance of C. jejuni (Oh et al., 2015). In this study, we demonstrated that ahpC is also a key player in C. jejuni’s hyper-aerotolerance (Figure 4). Enhanced resistance to oxidative stress may result in hyper-aerotolerance; this enables hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni to survive easily under aerobic conditions during food processing, increasing risks of foodborne transmission to humans. Interestingly, it has been reported that C. jejuni strains in CC-21 from poultry and human clinical samples frequently exhibit hyper-invasiveness than strains in other CCs (Fearnley et al., 2008). C. jejuni strains in CC-21 usually (85.7%) have the sialylated lipooligosaccharide (LOS) class C and are highly invasive than isolates from other CCs (Habib et al., 2009). Taken our findings and these previous reports together, C. jejuni strains in CC-21 are often hyper-aerotolerant and likely to be invasive. Presumably, this would be why CC-21 is frequently involved in human infection and outbreaks (Sails et al., 2003; Nielsen et al., 2010).

To be the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the prevalence of hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni in chicken meats. Importantly, hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni isolates are distributed mostly in the CCs that are often implicated in human infection, suggesting potential impact of hyper-aerotolerance on food safety and public health. Although we showed oxidative stress defense contributes to hyper-aerotolerance in C. jejuni in this study, there seems to be other unknown factors associated with hyper-aerotolerance since ahpC reduced aerotolerance, but not completely eliminated it (Figure 4). Based on the differential clustering of the LOS class in CC-21 (Habib et al., 2009), possibly some other genetic variations might also be involved in hyper-aerotolerance. Therefore, an extensive future study, such as whole genome sequencing, will be needed to further characterize hyper-aerotolerant C. jejuni and to reveal its implication in human infection.

Author Contributions

Design of the project: EO, LM, and BJ; Performance of the experiments: EO; Data analysis: EO, LM, and BJ; Writing of the manuscript: EO, LM, and BJ.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency (ALMA) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01263

References

- Altekruse S. F., Stern N. J., Fields P. I., Swerdlow D. L. (1999). Campylobacter jejuni–an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5 28–35. 10.3201/eid0501.990104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack J. M., Harvey P., Jones M. A., Kelly D. J. (2008). The Campylobacter jejuni thiol peroxidases Tpx and Bcp both contribute to aerotolerance and peroxide-mediated stress resistance but have distinct substrate specificities. J. Bacteriol. 190 5279–5290. 10.1128/JB.00100-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhunia A. K. (2008). “Campylobacter and arcobacter,” in Foodborne Microbial Pathogens: Mechanisms and Pathogenesis, ed. Bhunia A. K. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bohaychuk V., Gensler G., King R., Manninen K., Sorensen O., Wu J., et al. (2006). Occurrence of pathogens in raw and ready-to-eat meat and poultry products collected from the retail marketplace in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. J. Food Prot. 69 2176–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call D. R., Borucki M. K., Loge F. J. (2003). Detection of bacterial pathogens in environmental samples using DNA microarrays. J. Microbiol. Methods 53 235–243. 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00027-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott K. A., Harðardóttir H., Georgsson F., Reiersen J., Friðriksdóttir V., Gunnarsson E., et al. (2008). Broiler Campylobacter contamination and human campylobacteriosis in Iceland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 6483–6494. 10.1128/AEM.01129-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon J.-W., Hyeon J.-Y., Park J.-H., Song K.-Y., Seo K.-H. (2012). Comparison of 2 types of broths and 3 selective agars for the detection of Campylobacter species in whole-chicken carcass-rinse samples. Poult. Sci. 91 2382–2385. 10.3382/ps.2011-01980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles F., Maiden M. (2012). Campylobacter sequence typing databases: applications and future prospects. Microbiology 158 2695–2709. 10.1099/mic.0.062000-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S., Ge B., Zheng J., Meng J. (2005). Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella serovars in organic chickens from Maryland retail stores. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 4108–4111. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4108-4111.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle K., Colles F., Wareing D., Ure R., Fox A., Bolton F., et al. (2001). Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 14–23. 10.1128/JCM.39.1.14-23.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley C., Manning G., Bagnall M., Javed M. A., Wassenaar T. M., Newell D. G. (2008). Identification of hyperinvasive Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from poultry and human clinical sources. J. Med. Microbiol. 57 570–580. 10.1099/jmm.0.47803-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib I., Louwen R., Uyttendaele M., Houf K., Vandenberg O., Nieuwenhuis E. E., et al. (2009). Correlation between genotypic diversity, lipooligosaccharide gene locus class variation, and Caco-2 cell invasion potential of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from chicken meat and humans: contribution to virulotyping. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 4277–4288. 10.1128/AEM.02269-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A. N., Andersen M., Dalsgaard A., Baggesen D. L., Nielsen E. (2005). Development of real-time PCR and hybridization methods for detection and identification of thermophilic Campylobacter spp. in pig faecal samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99 292–300. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush N. O., Miller W. G., De Reuse H., Mendz G. L. (2007). Oxygen requirement and tolerance of Campylobacter jejuni. Res. Microbiol. 158 644–650. 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J., Nolan A., Gibney S., O’brien S., Mcmahon M., Mckenzie K., et al. (2011). Deteminants of cross-contamination during home food preparation. Br. Food J. 113 280–297. 10.1108/00070701111105349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-C., Oh E., Kim J., Jeon B. (2015). Regulation of oxidative stress resistance in Campylobacter jejuni, a microaerophilic foodborne pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 6:751 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque S., Frost E., Arbeit R. D., Michaud S. (2008). Multilocus sequence typing of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from humans, chickens, raw milk, and environmental water in Quebec. Can. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 3404–3411. 10.1128/JCM.00042-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little C. L., Richardson J. F., Owen R. J., De Pinna E., Threlfall E. J. (2008). Prevalence, characterisation and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter and Salmonella in raw poultrymeat in the UK, 2003–2005. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 18 403–414. 10.1080/09603120802100220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber P., Bartelt E. (2007). Enumeration of Campylobacter spp. on the surface and within chicken breast fillets. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrell R. E., Wachtelt M. R. (1999). Novel detection techniques for human pathogens that contaminate poultry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 10 273–278. 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G., Dowson C. G., Bagnall M. C., Ahmed I. H., West M., Newell D. G. (2003). Multilocus sequence typing for comparison of veterinary and human isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 6370–6379. 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6370-6379.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros D. T., Sattar S. A., Farber J. M., Carrillo C. D. (2008). Occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in raw and ready-to-eat foods and in a Canadian food service operation. J. Food Prot. 71 2087–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E. M., Fussing V., Engberg J., Nielsen N., Neimann J. (2006). Most Campylobacter subtypes from sporadic infections can be found in retail poultry products and food animals. Epidemiol. Infect. 134 758–767. 10.1017/S0950268805005509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L. N., Sheppard S., Mccarthy N., Maiden M., Ingmer H., Krogfelt K. (2010). MLST clustering of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from patients with gastroenteritis, reactive arthritis and Guillain–Barré syndrome. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108 591–599. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04444.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Jeon B. (2014). Role of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) in the biofilm formation of Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS ONE 9:e87312 10.1371/journal.pone.0087312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Mcmullen L., Jeon B. (2015). Impact of oxidative stress defense on bacterial survival and morphological change in Campylobacter jejuni under aerobic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 6:295 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C. (2001). Arcobacter spp in food: isolation, identification and control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 12 263–275. 10.1016/S0924-2244(01)00090-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palacios G. M. (2007). The health burden of Campylobacter infection and the impact of antimicrobial resistance: playing chicken. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 701–703. 10.1086/509936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sails A. D., Swaminathan B., Fields P. I. (2003). Utility of multilocus sequence typing as an epidemiological tool for investigation of outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 4733–4739. 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4733-4739.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J., Leite D., Fernandes M., Mena C., Gibbs P. A., Teixeira P. (2011). Campylobacter spp. as a foodborne pathogen: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2:200 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelling W., Matsuda M., Moore J., Dooley J. (2006). Under the microscope: Arcobacter. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 42 7–14. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Vancanneyt M., Pot B., Mels L., Hoste B., Dewettinck D., et al. (1992). Polyphasic taxonomic study of the emended genus Arcobacter with Arcobacter butzleri comb. nov. and Arcobacter skirrowii sp. nov., an aerotolerant bacterium isolated from veterinary specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42 344–356. 10.1099/00207713-42-3-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet A. H., Baillon M.-L. A., Penn C. W., Ketley J. M. (2001). The iron-induced ferredoxin FdxA of Campylobacter jejuni is involved in aerotolerance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 196 189–193. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Clark C. G., Taylor T. M., Pucknell C., Barton C., Price L., et al. (2002). Colony multiplex PCR assay for identification and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 4744–4747. 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4744-4747.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiley H., Van Den Akker B., Giglio S., Bentham R. (2013). The role of environmental reservoirs in human campylobacteriosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10 5886–5907. 10.3390/ijerph10115886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. J., Gabriel E., Leatherbarrow A. J., Cheesbrough J., Gee S., Bolton E., et al. (2008). Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000203 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. T., Davis L. M., Dirita V. J. (2007). Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5 665–679. 10.1038/nrmicro1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Zhang X., Hu Y., Jiao X.-A., Huang J. (2015). Multilocus Sequence types of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from different sources in Eastern China. Curr. Microbiol. 71 341–346. 10.1007/s00284-015-0853-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.