Abstract

Mutations in MYBPC3, the gene encoding cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C), account for ~40% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) cases. Most pathological MYBPC3 mutations encode truncated protein products not found in tissue. Reduced protein levels occur in symptomatic heterozygous human HCM carriers, suggesting haploinsufficiency as an underlying mechanism of disease. However, we do not know if reduced cMyBP-C content results from, or initiates the development of HCM. In previous studies, heterozygous (HET) mice with a MYBPC3 C’-terminal truncation mutation and normal cMyBP-C levels show altered contractile function prior to any overt hypertrophy. Therefore, this study aimed to test whether haploinsufficiency occurs, with decreased cMyBP-C content, following cardiac stress and whether the functional impairment in HET MYBPC3 hearts leads to worsened disease progression. To address these questions, transverse aortic constriction (TAC) was performed on three-month-old wild-type (WT) and HET MYBPC3-truncation mutant mice and then characterized at 4 and 12 weeks post-surgery. HET-TAC mice showed increased hypertrophy and reduced ejection fraction compared to WT-TAC mice. At 4 weeks post-surgery, HET myofilaments showed significantly reduced cMyBP-C content. Functionally, HET-TAC cardiomyocytes showed impaired force generation, higher Ca2+ sensitivity, and blunted length-dependent increase in force generation. RNA sequencing revealed several differentially regulated genes between HET and WT groups, including regulators of remodeling and hypertrophic response. Collectively, these results demonstrate that haploinsufficiency occurs in HET MYBPC3 mutant carriers following stress, causing, in turn, reduced cMyBP-C content and exacerbating the development of dysfunction at myofilament and whole-heart levels.

Keywords: Cardiac myosin binding protein-C, Haploinsufficiency, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, MYBPC3, Mouse Models

1. Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease that results in pathological enlargement of the heart and has been shown to be caused primarily by mutations in genes encoding sarcomere proteins [1, 2]. Mutations in the MYBPC3 gene, which encodes the sarcomeric transverse-filament protein cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C), account for approximately 40% of identified HCM-associated mutations [3, 4]. Additionally, most MYBPC3 variants known to cause HCM have been predicted to encode mutant proteins with C’-terminal truncations that prevent protein incorporation into the sarcomere [5, 6]. The vast majority of MYBPC3 truncation mutations studied have not resulted in the identification of mutant protein in cardiac tissue from affected HCM patients [7-11]. This means that the truncated protein is either not expressed or is rapidly degraded, suggesting that the pathology could be caused by haploinsufficiency of the MYBPC3 gene, which occurs when a single functional copy of a gene is insufficient to achieve a normal phenotype. In support of this mechanism, tissue samples from human symptomatic heterozygous carriers of MYBPC3 truncation mutations have shown reduced cMyBP-C levels compared to samples from donor hearts [12]. In addition, heterozygous (HET) mouse models of several MYBPC3 truncation mutations have shown various changes in cMyBP-C, ranging from normal content to almost 50% reductions in cMyBP-C level [13-16]. These models have also shown variable phenotypes, including mild hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction and altered Ca2+ sensitivity of force development [13-18]. These findings from human tissue and mouse models suggest that haploinsufficiency does occur in MYBPC3 truncation mutation carriers. However, since it is difficult to collect tissue samples from asymptomatic human carriers of these mutations, it remains unclear if reduced cMyBP-C stoichiometry causes the development of symptomatic cardiomyopathy, or if hypertrophic remodeling presages this reduction.

Heterozygous carriers of these mutations often have incomplete penetrance and variable onset of disease [19], suggesting that other genetic or environmental factors modify the phenotype and influence the development of disease [20]. This view has been supported by studies of models of HCM-causing mutations in MYBPC3 and other genes that have been shown to be altered by genetic modifiers [20-22] and external stress [23], contributing to dysfunction and affecting the course of disease. Establishing how specific gene mutations with a common mechanism of action (i.e. haploinsufficiency) are influenced by modifiers such as stress will inform our understanding of the susceptibility to the development of HCM and heart failure (HF) in human mutation carriers.

In order to study the effects of stress on haploinsufficiency of MYBPC3 we used a mouse model generated by McConnell et al. (1999) of a MYBPC3 truncating mutation (MYBPC3(t/t)) encoding an undetected protein product containing novel C’ amino acids which prevent cMyBP-C incorporation into the sarcomere [13, 24, 25]. These homozygous mice have previously been described as having a null cMyBP-C background, but remain viable, exhibiting myocardial hypertrophy and decreased contractility at a young age [13, 26]. We recently reported that this HET mouse has reduced cardiomyocyte force generation and diastolic dysfunction, whileexhibiting no changes in Ca2+ sensitivity and maintaining normal cMyBP-C stoichiometry in the absence of hypertrophy [18]. However, the effect of cardiac stress on the development of HCM phenotype in HET mice remains unknown. In the current study, we used this HET mouse model and a pressure-overload surgical approach to determine 1) the impact of hypertrophic remodeling on cMyBP-C stoichiometry and 2) the predisposition for developing hypertrophy in response to cardiovascular stress. Our results demonstrate that cardiac stress in heterozygous MYBPC3 truncation mutant carriers causes alterations in the levels of cMyBP-C and worsens contractile function, leading to a more severe pathological phenotype.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animal Models and Surgical Procedure

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Loyola University Chicago and followed the policies described in the Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. HET mice carrying an MYBPC3 truncating mutation were bred from a homozygous line originally generated in the Seidman lab [13]. Wild-type (WT) and HET mice used in this experiment were both in the FVB/N background and were between 10 and 12 weeks of age when transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery was performed. These mice carry a knock-in mutation that causes skipping of exon 30 and a frame shift that results in the inclusion of a premature stop codon. The predicted protein from this gene is not detectable, consistent with many human MYBPC3 truncation mutations [4]. TAC was performed to induce pressure-overload hypertrophy in both WT and HET genotypes, along with a sham surgical control as previously described [27]. Briefly, surgery was performed using 5% isoflurane for induction and during the early phases of the procedure, including intubation and any steps where bone was cut, followed by a steady level of anesthesia using 2% isoflurane. Mice were mechanically ventilated (Mini-Vent, Hugo Sachs 845), and a partial midline thoracotomy to the level of the third rib was performed to expose the aortic arch. The aorta was isolated and constricted by tying a saline-soaked 7-0 silk suture around the transverse aorta against a blunted 27 gauge needle, followed by removal of the needle and closure of the chest.

2.2 Echocardiography analysis

All echocardiography data were acquired using a VisualSonics Vevo 2100 (Fuji Film, Toronto) with a MS-550D 22-55 MHz transducer as described previously [18], with the exception of transverse aortic blood flow measurements which were made using a MS-250 13-24 MHz transducer. Mice were kept sedated using 1.5% – 2.0% isoflurane in 100% oxygen. Proper placement of the aortic band was verified using power-Doppler to measure peak blood flow velocity across the transverse aorta. Cardiac remodeling and function were measured by M-mode taken from the parasternal long axis at the mid-papillary level. Diastolic parameters were measured by power-Doppler and tissue-Doppler using an apical four-chamber view of the heart.

2.3 Steady-state force measurements

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from frozen tissue and detergent-skinned using Triton X-100 as previously described [18]. Following detergent skinning cardiomyocytes were attached to a force transducer and a high-speed piezo translator (Thor Labs, Newton, NJ). Buffers containing varying Ca2+ concentrations (pCa 10.0 – pCa 4.5) were perfused into the cell chamber and corresponding force generation was measured. To assess changes in length-dependency of Ca2+ sensitivity of force development, cardiomyocytes were evaluated at sarcomere lengths (SL) of 1.9 μm and 2.3 μm. SL was measured using a Leica DM IRB microscope with a 40× objective and processed with custom-made LabView software (National Instruments, Austin, TX) with fast Fourier transform analysis of cardiomyocyte images. A modified Hill equation was used to fit the force-pCa curves: P/PO = [Ca2+]n/(kn+[Ca2+]n), where n is the Hill-slope and k is the pCa50. Measurements were not used if total force run-down was greater than 20% of initial maximal force after the final maximal activation at either SL.

2.4 Analysis of mRNA levels

Total RNA was isolated by homogenizing tissue using TriZol and a Mini-Beadbeater (Biospec), followed by chloroform precipitation and purification using an RNA binding column (BioRad 732-6830). Purified RNA was used to make cDNA with 1μg of RNA template using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad 170-8891). Samples were used for qPCR using SybrGreen and primers against MYBPC3 (IDT Mm.PT.53a.2930640), MYH7 (Mm.PT.56a.17465550.g), and NPPA (Mm.PT.56a.10008284.g), with a TaqMan GAPDH (Applied Biosystems Mm00486742m1) primer set used as a reference gene. A Bio-Rad CFX96 thermocycler was used for qPCR analysis with a cycle protocol of 10 minutes at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. Normalized gene expression was calculated using an amplification efficiency-corrected ΔΔCq equation [28].

2.5 RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) Analysis

RNA-Seq was performed on cDNA samples made from isolated RNA, as described for qPCR. Samples from three mice per group were pooled for analysis. cDNA libraries were generated from these samples, which were sequenced followed by read alignment as previously described [20, 29]. The number of reads were normalized per million. Changes were studied in genes that differed between groups with ≥ 1.5-fold up-regulation or ≤ 0.6-fold down-regulation.

2.6 Analysis of protein level

Frozen mouse hearts were homogenized for total protein or myofilament-enriched fractions. All buffers used for protein isolation contained protease inhibitors (Roche 4693159001) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma P5726 and P0044). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on either 10% polyacrylamide or 4-15% polyacrylamide gradient gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 4°C at 300mA for 3 hours in Tris glycine with 10% methanol. Membrane blocking and antibody incubations were performed using Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 1% Tween-20 with blocking buffer (Roche 11921681001). Antibodies recognizing cardiac-specific N’-terminal regions of cMyBP-C (Santa Cruz 137180), actin (Sigma A2172), and phospho cTnI (Cell Signaling 4004) were used for Western blot with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies for detection (Santa Cruz SC-2004 and SC-2314). ECL Prime (GE Life Sciences RPN2232) reagent was used for detection and blots were imaged using ChemiDoc+ (Bio-Rad). Myosin heavy chain isoforms were separated as previously described [18], and gels were stained with SYPRO-Ruby (Bio-Rad 170-3138). Protein levels from all blots and gels were quantified using ImageJ.

2.7 Statistical Analysis

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. All comparisons were made using Two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-hoc test, unless otherwise noted. Significance was established as P < 0.05. RNA-Seq samples were compared using a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate test with significance defined as P < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1 Heterozygous hearts show increased hypertrophy following TAC

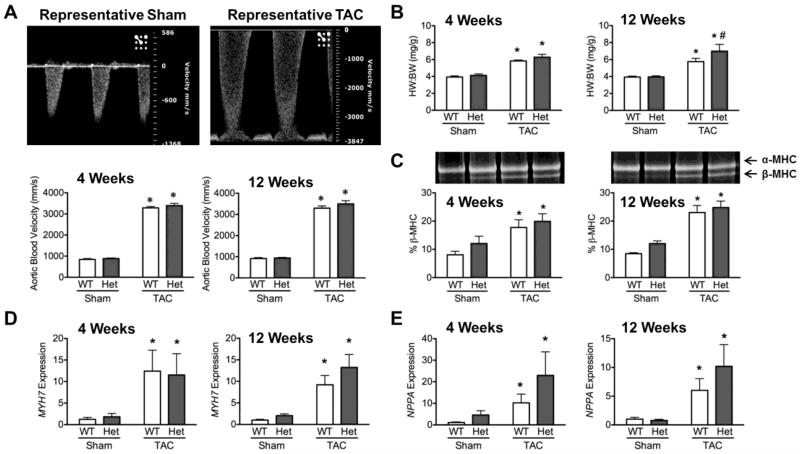

In order to determine whether HET mice develop more severe hypertrophy following stress, TAC surgery was performed on three-month old WT and HET mice. To measure the severity of the constriction, blood flow velocity across the transverse aorta was used as an inclusion criterion, with velocities of ≥3000mm/s (≥36mmHg) defined as the mark for successful and persistent TAC. As expected, this parameter was significantly increased in both WT and HET mice following TAC when compared to sham controls, and remained the same between 4 and 12 weeks (Fig.1A). Importantly, this value was not significantly altered between WT-TAC and HET-TAC mice at either 4 or 12 weeks. Despite equal pressure-overload stress between WT and HET mice, HET-TAC mice showed significantly increased HW:BW ratios compared to WT-TAC mice at 12 weeks (Fig. 1B), indicating that HET mice were more affected by pressure-overload stress. As expected, expression of the hypertrophic remodeling markers MYH7 and NPPA, as assessed by qPCR, showed significant up-regulation in WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups compared to sham controls (Fig. 1D & E). Elevation of β-MHC was confirmed at the protein level by separating α and β myosin isoforms. This revealed a significant increase of β-MHC in WT-TAC and HET-TAC hearts compared to sham controls (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

TAC-induced pressure-overload causes more severe hypertrophy in HET hearts compared to WT. (A) Representative pulse-wave Doppler of blood-flow velocities across the transverse aorta following sham and TAC procedures. Quantification of transverse aortic blood flow velocities shows significant increases in both WT and HET mice following TAC compared to sham controls. (B) Hypertrophy as assessed by the ratio of heart weight to body weight shows significant increases in HET hearts following TAC compared to WT-TAC controls. (C) SYPRO-Ruby-stained SDS-PAGE shows separation of myosin heavy chain isoforms. Elevated β-MHC indicates hypertrophic remodeling in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC hearts. (D & E) Gene expression levels of the hypertrophic markers MYH7 and NPPA relative to GAPDH show significant increase in expression of both genes in WT-TAC and HET-TAC hearts compared to sham controls. * P < 0.05 compared to sham control; # P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

3.2 In vivo systolic function is significantly impaired in HET-TAC hearts

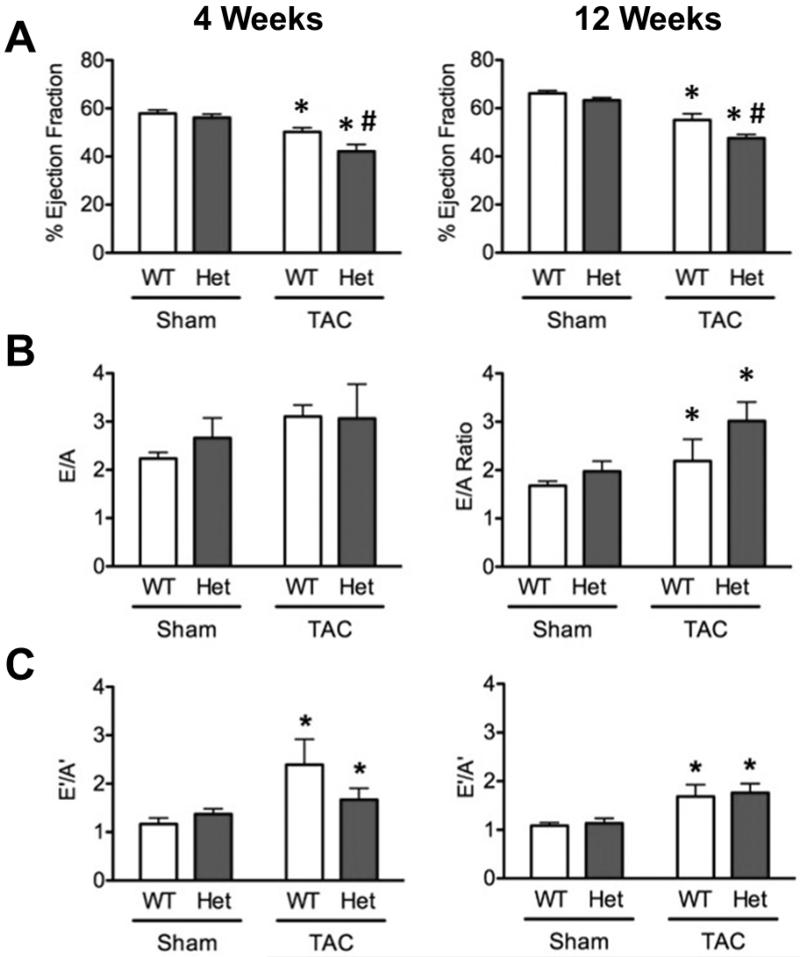

Echocardiography was used to assess in vivo functional and morphological consequences of TAC on WT and HET hearts. Analysis of M-mode echocardiography images showed significantly increased wall thicknesses in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups at 4 weeks and 12 weeks compared to sham controls, consistent with hypertrophic remodeling (Supplemental Table 1 and 2). Systolic function was significantly impaired at 4 and 12 weeks in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups compared to sham controls. Moreover, HET-TAC hearts also showed significantly reduced ejection fraction compared to WT-TAC at both 4 and 12 weeks post-surgery (Fig. 2A), demonstrating a worsened response to TAC in the HET mice. The diastolic functional parameters measuring left-ventricular filling via blood flow (E/A) and tissue motion (E’/A’) showed significantly elevated ratios in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups compared to sham controls (Fig. 2B & C).

Fig. 2.

Heterozygous mice have systolic deficits compared to WT following TAC. (A) Systolic function derived from parasternal long axis M-mode imaging shows significantly reduced ejection fraction in HET-TAC mice compared to WT-TAC mice at 4 and 12 weeks following surgery. As expected, both TAC groups show significantly impaired systolic function compared to sham controls. (B & C) Diastolic parameters E/A measured by pulse-wave Doppler and E’/A’ showed significant alterations in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC hearts. * P < 0.05 compared to sham control; # P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

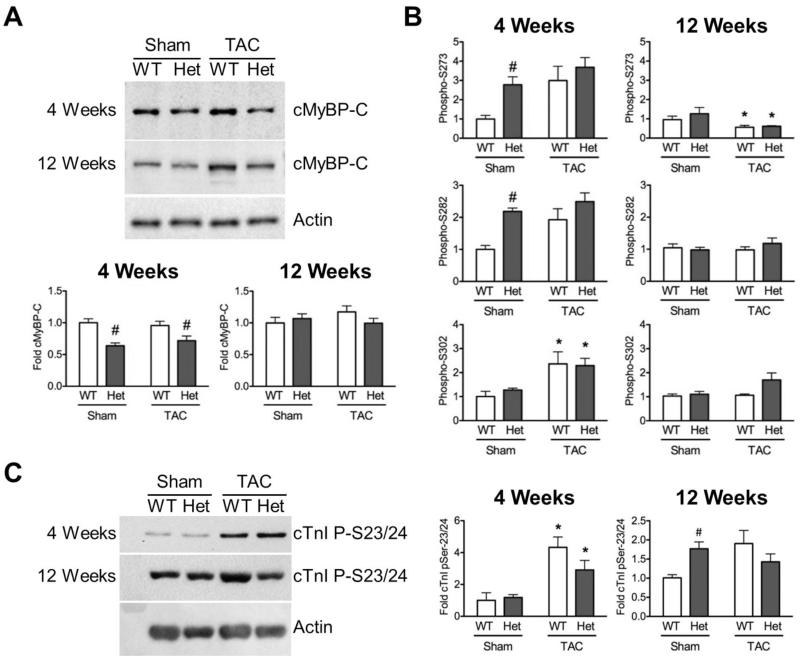

3.3 Levels of cMyBP-C are transiently decreased in HET hearts following surgery

Following the observations of increased hypertrophy and deficits in systolic function in HET hearts post-TAC, the effect of cardiac stress on cMyBP-C stoichiometry was interrogated using myofilament protein fractions and Western blot analysis. Levels of MYBPC3 transcript were consistently reduced to approximately 60% in all HET animals, consistent with previous reports [13, 18, 26]. Levels of total cMyBP-C normalized to actin loading showed significantly reduced cMyBP-C content in sarcomeres from HET-TAC samples compared to WT-TAC (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, compared to naïve HET mice at baseline [18], levels of cMyBP-C were also reduced in HET-sham myofilaments compared to WT-sham. Reduced levels of cMyBP-C were only observed at 4 weeks post-surgery, with no significant differences in cMyBP-C levels observed at 12 weeks between any of the groups. Also, no changes were observed in cMyBP-C level between WT-sham and WT-TAC groups at either time point.

Fig. 3.

Levels of cMyBP-C are transiently reduced in HET hearts. (A) Western blot analysis of myofilament fractions showed significantly reduced cMyBP-C at 4 weeks post-surgery in both HET-sham and HET-TAC groups with this alteration not observed at 12 weeks. (B) Phosphorylation of cMyBP-C at Ser-302, as assessed by antibodies that recognize site-specific phosphorylated serines, shows significant increase in cMyBP-C phosphorylation at 4 weeks in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups, as well as HET-sham in Ser-273 and Ser-282 sites. By 12 weeks, phosphorylated cMyBP-C levels were significantly lower at Ser-273 in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups. (C) The phosphorylation status of cTnI serine 23/24 was assessed by Western blot and revealed significant hyperphosphorylation at 4 weeks in both TAC groups compared to sham controls. At 12 weeks, HET-sham showed significantly elevated cTnI phosphorylation. * P < 0.05 compared to sham control; # P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

The phosphorylation status of cMyBP-C is known to be a key regulator of sarcomere function [30, 31]. Therefore, we assessed cMyBP-C phosphorylation by Western blot using three site-specific antibodies that recognize phosphorylated Serine 273, 282, and 302 [32, 33]. To correct for alteration in cMyBP-C content, levels of phospho-cMyBP-C were normalized to total cMyBP-C levels. At 4 weeks post-surgery, both TAC groups had increased phosphorylation levels. However, because of significant hyper-phosphorylation of HET-sham at Ser 273 or 282 at these residues, the increase in phosphorylation observed in the TAC groups did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3B). By 12 weeks post-surgery, phosphorylated cMyBP-C had fallen to non-significant levels in the TAC groups with the exception of Ser-273, which showed significantly reduced phosphorylation levels. Reduced phosphorylation at this time point is consistent with cMyBP-C hypo-phosphorylation observed during the development of HF [34].

Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) is another key signaling target in the sarcomere, where increased PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-22/23 (Ser-23/24 in human) causes decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development [35, 36]. To assess changes in the levels of phosphorylated cTnI, Western blotting with a site-specific antibody against phosphorylated Ser-22/23 was performed. This revealed significant hyper-phosphorylation in both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups compared to respective sham controls at 4 weeks. At 12 weeks, a statistically non-significant elevation was observed in both TAC groups, compared to WT sham. The lack of significance of this increase at 12 weeks results from a significant increase in cTnI phosphorylation in HET-sham compared to WT-sham, which was not detected at 4 weeks (Fig. 3C).

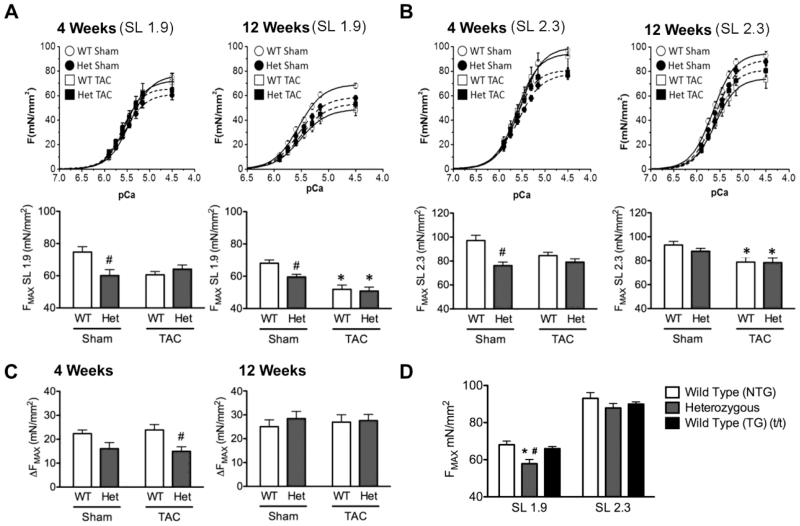

3.4 Heterozygous cardiomyocytes show deficits in force development and length-dependent activation

Alterations in cMyBP-C stoichiometry and changes in myofilament phosphorylation levels have been shown to affect sarcomere contractility [17, 37, 38]. To assess functional changes at the cellular level, detergent-skinned cardiomyocytes were evaluated for maximal force generation and Ca2+ sensitivity of force development at short (1.9μm) and long (2.3μm) SL (Fig. 4A & B). At 4 weeks post-surgery, HET-sham cardiomyocytes showed significantly reduced force generation compared to WT-sham at both short and long SL (Fig. 4A & B). At 12 weeks post-surgery, HET-sham cardiomyocytes still showed significant deficits in maximal force development at SL 1.9μm, and both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups showed significant impairment of force development at both SLs compared to sham controls (Fig. 4A & B). Length-dependent increases in force development were significantly blunted in the HET genotype at 4 weeks, with HET-TAC showing significantly impaired length-dependent increase in force compared to WT-TAC (Fig. 4C). This deficit was not observed at 12 weeks post-surgery, by which time no significant changes could be observed between any of the groups. Force development at pCa 5.75 (diastolic Ca2+ levels) was also altered in HET mice 4 weeks post-TAC, with significantly elevated force development compared to WT-TAC, whereas this effect was not observed at 12 weeks (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 4.

Heterozygous cardiomyocytes show reduced force development and blunted length-dependent changes in force and calcium sensitivity. (A & B) Force-pCa curves generated at SL 1.9μm and SL 2.3μm. HET-sham cardiomyocytes showed a significant deficit in force development. At 12 weeks, both WT-TAC and HET-TAC groups showed impaired function. Two-way ANOVA at both SL detected significant genotype-specific effects at 12 weeks. (C) Length-dependent increase in force development was attenuated in HET-TAC compared to WT-TAC, as well as a significant genotype-specific effect at 4 weeks. This effect was not observed at 12 weeks. (D) Maximal force was not attenuated in WT(t/t) cardiomyocytes compared to non-transgenic WT controls, whereas HET cardiomyocytes showed dysfunction as reported previously. * P < 0.05 compared to sham control; # P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

Table 1.

Summary of force-pCa experiments four weeks post-surgery.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four Week Post-Surgery | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Sham | TAC | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Wild Type | Heterozygous | Wild Type | Heterozygous | ||

| 1.9 | FpCa 5.75 (mN/mm2)† | 17.3 ± 0.6 | 18.3 ± 1.5 | 15.1 ± 0.9 | 22.1 ± 2.2# |

| FMAX (mN/mm2) | 74.7 ± 3.4 | 60.1 ± 3.7# | 60.6 ± 2.0 | 64.1 ± 2.6 | |

| pCa50† | 5.45 ± 0.03 | 5.56 ± 0.02# | 5.52 ± 0.01* | 5.62 ± 0.03*# | |

|

|

|||||

| 2.3 | FpCa 5.75 (mN/mm2) | 33.8 ± 3.2 | 28.1 ± 2.6 | 29.4 ± 1.8 | 32.2 ± 2.5 |

| FMAX (mN/mm2) | 97.1 ± 4.4 | 76.2 ± 2.9# | 84.5 ± 2.9 | 79.1 ± 2.8 | |

| pCa50 † | 5.57 ± 0.02 | 5.61 ± 0.01 | 5.62 ± 0.01* | 5.67 ± 0.02*# | |

|

|

|||||

| ΔFMAX (mN/mm2) † | 22.4 ± 1.5 | 16.0 ± 2.6 | 23.9 ± 2.2 | 15.0 ± 1.9# | |

| ΔpCa50 † | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.02# | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | |

P < 0.05 compared to sham control

P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

Significance difference in genotype by 2-way ANOVA.

Table 2.

Summary of force-pCa experiments 12 weeks post-surgery.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twelve Week Post-Surgery | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Sham | TAC | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Wild Type | Heterozygous | Wild Type | Heterozygous | ||

| 1.9 | FpCa 5.75 (mN/mm2) | 20.7 ± 2.0 | 17.2 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.5 | 15.3 ± 1.7 |

| FMAX (mN/mm2) | 67.5 ± 2.1 | 57.9 ± 2.3# | 48.1 ± 4.4* | 52.8 ± 3.0* | |

| pCa50 † | 5.56 ± 0.02 | 5.55 ± 0.02 | 5.54 ± 0.02 | 5.52 ± 0.02 | |

|

|

|||||

| 2.3 | FpCa 5.75 (mN/mm2) | 37.8 ± 2.1 | 32.1 ± 1.6 | 26.6 ± 2.8 | 26.7 ± 2.6 |

| FMAX (mN/mm2) † | 91.1 ± 2.6 | 87.9 ± 2.4# | 73.1 ± 6.9* | 80.5 ± 4.1* | |

| pCa50 | 5.66 ± 0.02 | 5.61 ± 0.01 | 5.62 ± 0.02* | 5.59 ± 0.02* | |

|

|

|||||

| ΔFMAX (mN/mm2) | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 30.0 ± 3.2 | 25.0 ± 3.5 | 27.7 ± 2.4 | |

| ΔpCa50 † | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01# | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | |

P < 0.05 compared to sham control

P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

Significance difference in genotype by 2-way ANOVA.

3.4 Overexpression of MYBPC3 eliminates force deficits in the presence of the truncated allele

It has been proposed that MYBPC3 truncation mutations express small amounts of mutant protein, which despite being undetected, are able to exert a dominant-negative effect. To test this mechanism we used a well-characterized mouse line that has transgenic copies of WT MYBPC3 with an α-myosin heavy chain promoter expressed in the homozygous MYBPC3 truncation background (t/t), a model known as WT(t/t) [32]. This model shows a 4-fold increase in the level of MYBPC3 transcript compared to non-transgenic (NTG) WT mice and 100% cMyBP-C stoichiometry [32]. If truncated alleles do confer force deficits, then the WT(t/t) model would be expected to suffer a similar reduction in force compared to HET cardiomyocytes based on the presence of two truncated alleles. Measurements of maximal force generation in NTG naïve WT mice and HET mice, as have been used throughout this study, as well as the naïve transgenic WT(t/t) mouse, show no impaired force development in the WT(t/t) group (Fig. 4D), even though HET cardiomyocytes exhibited dysfunction, as demonstrated previously [15].

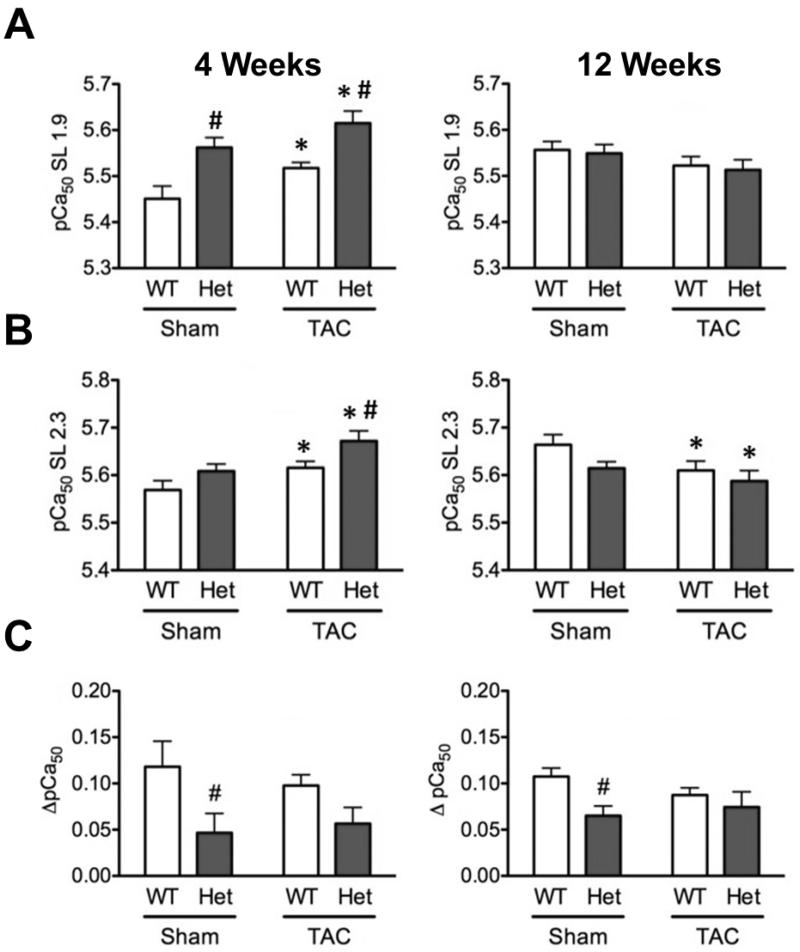

3.5 Heterozygous cardiomyocytes show increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development

Other models of HET MYBPC3 truncation mutations have shown increase in Ca2+ sensitivity of force development [39]. In the present study, force-pCa analysis showed a significant increase in Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in HET-sham compared to WT-sham at 4 weeks, as well as a significant increase in HET-TAC compared to WT-TAC (Fig 5A & B), with both TAC groups showing significantly increased Ca2+ sensitivity compared to sham controls. These effects were not observed at SL 1.9 at 12 weeks and, indeed, were reversed at SL 2.3 at 12 weeks, with both TAC groups showing significant desensitization. Also, length-dependent Ca2+ sensitization was significantly blunted in HET-sham compared to WT-sham at both 4 and 12 weeks (Fig. 5C), and a significant difference in the genotype factor between WT and HET by two-way ANOVA showed that HET groups had significantly blunted length-dependent Ca2+ sensitization at 4 weeks.

Fig. 5.

Calcium sensitivity of force development was significantly increased in both HET-sham and HET-TAC groups at 4 weeks, with HET-TAC showing significant sensitization compared to WT TAC. (A & B) Calcium sensitivity of force development at short SL (A) and long SL (B) was increased in HET-sham compared to WT-sham at 4 weeks, with significant genotype-specific effects observed at both time points, including significant desensitization at 12 weeks at long SL in both TAC groups compared to sham control. This effect was not observed at 12 weeks (C). * P < 0.05 compared to sham control; # P < 0.05 compared to genotype control.

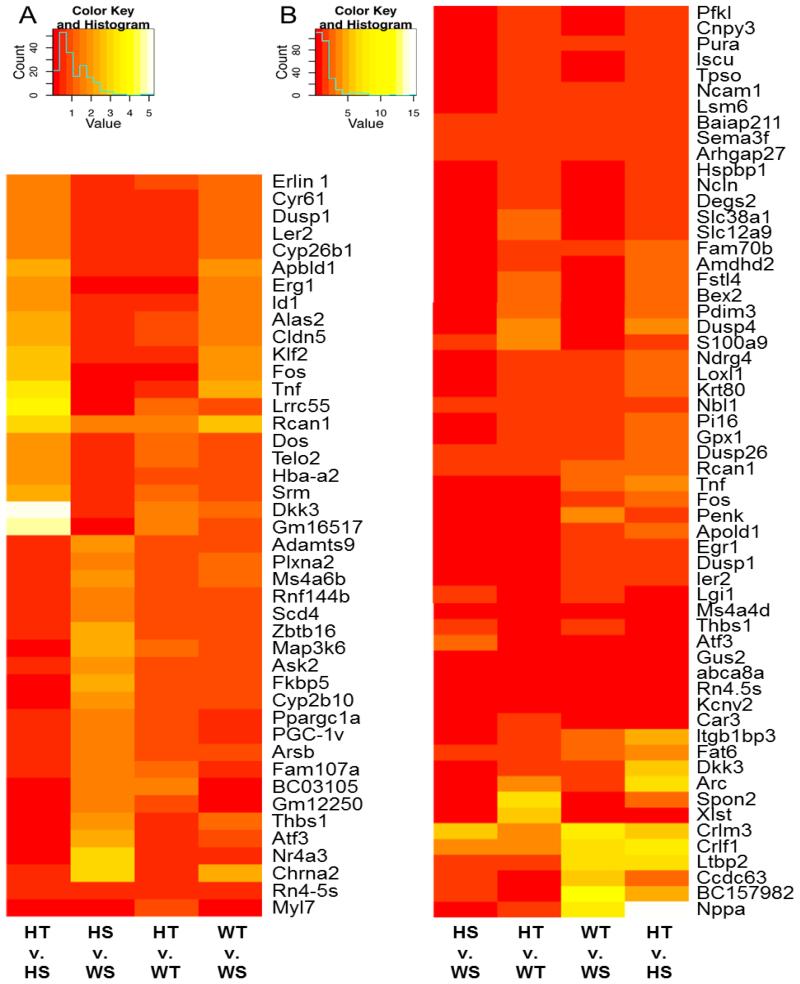

3.6 RNA-Seq identifies gene expression differences between WT and HET hearts

Other mouse models of HET MYBPC3 truncation mutations have had large-scale gene expression analysis performed in an effort to identify novel pathways that provide an explanation for the molecular dysfunction observed in HCM. In order to extend this approach and characterize differences in gene expression in the HET model reported in this work, RNA-Seq was performed on samples isolated from WT and HET mice 12 weeks following sham and TAC surgery. Significantly altered genes were found in HET-sham compared to WT-sham (Supplementary Table 3 & 4), as well as changes between HET-TAC and WT-TAC (Supplementary Table 5 & 6). These differentially regulated genes show changes in several transcription factors, kinases and phosphatases, and components of hypertrophic signaling pathways (Fig. 6). Additionally, the HET group showed some common up- or down-regulated genes, including up-regulation of anti-hypertrophic factor calcipressin-1 and down-regulation of Fos, which is required for AP-1 signaling.

Fig. 6.

RNA-Seq shows clusters of genes that are differentially regulated in HET hearts after sham or TAC surgery. Heat maps representing normalized fold-change gene expression per million reads are illustrated between groups for the genes significantly altered in HET-sham (HS) versus WT-sham (WS) (A) and in HET-TAC (HT) versus WT-TAC (WT) (B). The fold change, up or down, is represented in the keys for the respective panels.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that mice carrying a HET MYBPC3 truncation mutation exhibit transient decreases in cMyBP-C content following surgical stress and develop a severe disease phenotype following pressure overload. When HET mice are stressed with TAC surgery they develop greater cardiac hypertrophy compared to WT controls. As supported by evidence in the present study, HET hearts undergo more severe hypertrophic remodeling and transient reduction in cMyBP-C levels, show impaired length-dependency of force and Ca2+ sensitivity, and have significantly impaired systolic function following TAC compared to WT mice. The conclusions drawn from these experiments are that 1) HET mice are predisposed to severe HF and 2) insufficient expression of cMyBP-C plays a role in the development of HF in HET mice. These observations demonstrate that cardiac stress has a more severe effect on carriers of HCM-causing MYBPC3 mutations and provides further rationale for studying the underlying molecular mechanisms of HCM in patients with MYBPC3 mutations.

We previously reported that this HET mouse showed subtle deficits in cardiomyocyte force generation and diastolic function, while still maintaining normal levels of cMyBP-C [18]. In the present study, one unexpected observation was the transient reduction of cMyBP-C levels in HET mice following sham surgery, suggesting that this transient reduction is related to stress generally and not to hypertrophic remodeling specifically. Since sham surgery consists of prolonged ventilation and large surgical incision, it is not surprising that this alone would be stressful for an animal. However, taking these data and the dysfunction this model exhibits under baseline conditions [18], together with observations from other HET mouse models that exhibit decreased cMyBP-C content [15, 17], it is possible that the mouse strain in our current experiments may only barely maintain normal cMyBP-C levels under baseline conditions [18]. Increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development has been identified as an early sign of dysfunction prior to hypertrophic remodeling in other HET MYBPC3 truncation mutation mouse models [39]. This sensitization is also interesting in this study, as it occurs in HET mice irrespective of the phosphorylation status of cTnI. In another study, the HET MYBPC3 mouse showed no significant increases in Ca2+ sensitivity under baseline conditions [18]. However, in the present study, these HET mice did show Ca2+ sensitization following both sham and TAC surgery, respectively, with unaltered and increased cTnI phosphorylation.

In addition to transiently reduced protein levels, following sham surgery HET mice show a number of differences from their baseline state [18], including increased phosphorylation levels of cMyBP-C and increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development, with blunted length-dependent increases in force development and Ca2+ sensitization. The reason for the observed increase in cMyBP-C phosphorylation in these mice may be an alteration in signaling caused by additional dysfunction following surgery. However, since the levels of PKA-specific Ser22/23 sites on cTnI are unaltered, it is unlikely that increased PKA signaling is responsible for the increase in cMyBP-C phosphorylation in the HET-sham hearts. Dysfunction in the HET mouse following sham surgery is also interesting because it demonstrates that a non-cardiac-specific stress considerably less severe than TAC was able to cause perturbations compared to WT. This reinforces the hypothesis that carriers of these types of mutations are more susceptible to starting down the path towards cardiomyopathy by a variety of stressors, the study of which may explain the variable penetrance of HCM in these patients. These findings demonstrate that mice with HET MYBPC3 truncating mutations maintain normal phenotypes; however, in response to cardiac stress, they have increased susceptibility to HF.

The RNA-Seq experiment was performed in order to provide novel insights into the relationship between myofilament dysfunction and whole-organ pathology in these HET mice. Both HET-sham and HET-TAC groups showed an up-regulation of calcipressin, a negative regulator of the pro-hypertrophic factor calcineurin. Also interesting is the absence of regulatory disparities in nonsense-mediated RNA decay pathways, or in components of the ubiquitin proteasome system. This is surprising as other mouse models of MYBPC3 truncation mutations have shown alterations in these pathways that have been associated with cardiac dysfunction [16, 40]. Alterations were also observed between HET-sham and WT-sham, including altered expression of extracellular matrix remodeling genes. In particular, upregulation of thrombospondin and disintegrin-like metalloprotease was noted, which suggests tissue remodeling prior to the onset of hypertrophy and supports the involvement of fibroblasts in these processes.

Although some of these pathways may play a role in the worsened disease progression in HET hearts, the exact mechanism underlying the greater dysfunction in HET MYBPC3 mice remains undefined. In order to understand the pathophysiology of MYBPC3 truncation mutations, it is important to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism that explains why 1) HET cardiomyocytes have impaired force development, despite normal cMyBP-C levels, and 2) overexpression of WT cMyBP-C in the homozygous t/t background ameliorates this dysfunction. According to Sorajja, et al. (2000) the poison-polypeptide hypothesis holds that incorporated mutant proteins into the sarcomeres may act in a “dominant-negative” manner to cause myocyte dysfunction leading to compensatory hypertrophy [41]. However, because of the undetectable levels of truncated fragment reported in most of these truncation mutations in mice and humans, a poison-polypeptide mechanism involving a truncated fragment of cMyBP-C is unlikely to be a contributing factor in this dysfunction. Recent experiments by Witayavanitkul et al. have reinforced this notion. In these experiments N’ fragments of cMyBP-C were added to detergent-skinned cardiac myofilaments resulting in reduced myofilament force generation with a half-maximal effect at 4.41μM of cMyBP-C fragment and a maximal effect observed at approximately 30μM [42]. The amount of protein required for this dominant-negative effect is more clearly understood when the total amount of cMyBP-C in the cell, estimated at around 15μM, is taken into account [42]. The amount of N’ cMyBP-C required to affect myofilament function makes it very unlikely that an undetectable amount of mutant fragment could directly cause the cardiomyocyte dysfunction observed in the HET mice in this study.

Therefore, to address the cause of reduced myofilament force with preserved cMyBP-C levels, a potential future direction might be based on the hypothesis that reduced MYBPC3 expression is able to directly regulate cMyBP-C turnover. The HET model used in this study has been shown to express decreased MYBPC3 transcript, which is sufficient to maintain 100% cMyBP-C levels under baseline conditions [13, 18]. However, if the rate of new protein synthesis affects the rate of old protein removal from the sarcomere, then the turnover rate of the protein would be lower than normal, resulting in an older population of cMyBP-C. Several recent reports have identified that cMyBP-C is deleteriously regulated by oxidative modifications [43, 44], which may accumulate over time. This provides a potential role for fresh cMyBP-C to replace oxidized, dysfunctional protein. Testing this hypothesis, in terms of the effect of the rate of protein turnover on oxidative modifications would not be trivial, but could provide a simple mechanistic explanation for the dysfunction observed in these HET mice by showing that gene dosage directly affects protein turnover rate.

5. Conclusion

The high morbidity and mortality associated with cardiomyopathy in the human population emphasizes the need for a better understanding of the underlying molecular events leading to HF in cardiomyopathy [3] [45]. Genetic studies are now beginning to have a major impact on the diagnosis of HCM, as well as in guiding treatment and developing preventative strategies [21, 46]. Although much is known about which genes cause disease, relatively little is known about the molecular steps leading from the gene defect to the clinical phenotype and what factors modify expression of the mutant genes. Therefore, we attempted to analyze the role of exogenous cardiac stress in modulating phenotype development in relatively healthy mice with reduced MYBPC3 expression. As the majority of MYBPC3 truncation mutations in humans are heterozygous, fully elucidating the difference in stress response between WT and HET animals could provide valuable insight into the regulation of HCM development by external factors. As determined by the present study, HET carriers of MYBPC3 truncation mutations with normal cMyBP-C levels present with changes in protein stoichiometry following stress, as well as developing a severe HCM phenotype. Our results show that cMyBP-C levels are indeed altered following pressure overload as well as that surgical stress is sufficient to elicit this effect. Furthermore, HET MYBPC3 truncation mutation carriers show significant dysfunction at the single-cell and whole-heart levels following cardiac pressure-overload. These findings suggest that seemingly asymptomatic carriers of similar mutations may be at a greater risk of developing cardiomyopathy from a variety of environmental stressors, such as high blood pressure, diabetes and alcohol use, due to compounding effects of stress and haploinsufficiency of MYBPC3.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Surgical stress in Het MYBPC3 mice causes reduced cMyBP-C levels.

Decreased cMyBP-C is associated with decreased contractility following TAC.

Haploinsufficiency of cMyBP-C with cardiac stress aggravates HCM.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Michael Zillox of Loyola University Chicago’s Bioinformatics Department for making the RNA-Seq heat maps from the data provided. This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01HL-105826 and K02HL-114749 (to S. Sadayappan), HL-101297, HL-75494, and P01HL62426 (to de Tombe) and American Heart Association Grants 11PRE7240022 (to D. Barefield) and 14GRNT20490025 (to S. Sadayappan).

Abbreviations

- cMyBP-C

Cardiac myosin binding protein-C (referring to the polypeptide)

- cTnI

Cardiac troponin I

- E/A

Early/Atrial diastolic blood filling velocities

- E’/A’

Early/Atrial diastolic tissue motion velocities

- EF

Ejection fraction

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- HF

Heart failure

- HET

MYBPC3 heterozygous truncation mutant mouse

- MYBPC3

Cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene (referring to either genomic sequence or mRNA)

- SL

Sarcomere length

- TAC

Transverse aortic constriction

- WT

Wild-type mouse

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicting interests to disclose in relation to this work.

References

- [1].Maron B, Gardin J, Flack J, Gidding S, Kurosaki T, Bild D. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults: echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA study. Circulation. 1995;92:785–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Morita H, Rehm HL, Menesses A, McDonough B, Roberts AE, Kucherlapati R, et al. Shared genetic causes of cardiac hypertrophy in children and adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1899–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Harris SP, Lyons RG, Bezold KL. In the thick of it: HCM-causing mutations in myosin binding proteins of the thick filament. Circ Res. 2011;108:751–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Watkins H, Conner D, Thierfelder L, Jarcho JA, MacRae C, McKenna WJ, et al. Mutations in the cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene on chromosome 11 cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 1995;11:434–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bonne G, Carrier L, Bercovici J, Cruaud C, Richard P, Hainque B, et al. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene splice acceptor site mutation is associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 1995;11:438–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Niimura H, Bachinski L, Sangwatanaroj S, Watkins H, Chudley A, McKenna W, et al. Mutations in the gene for cardiac myosin-binding protein c and late-onset familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1248–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moolman JA, Reith S, Uhl K, Bailey S, Gautel M, Jeschke B, et al. A newly created splice donor site in exon 25 of the MyBP-C gene is responsible for inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with incomplete disease penetrance. Circulation. 2000;101:1396–402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Alcalai R, Seidman J, Seidman C. Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from bench to the clinics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:104–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].van Dijk SJ, Dooijes D, dos Remedios C, Michels M, Lamers JM, Winegrad S, et al. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Marston S, Copeland O, Jacques A, Livesey K, Tsang V, McKenna WJ, et al. Evidence from human myectomy samples that MYBPC3 mutations cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through haploinsufficiency. Circ Res. 2009;105:219–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].van Dijk S, Dooijes D, dos Remedios C, Michels M, Lamers J, Winegrad S, et al. Cardiac Myosin-Binding Protein C Mutations and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Haploinsufficiency, Deranged Phosphorylation, and Cardiomyocyte Dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McConnell B, Jones K, Farkin D, Arroyo L, Lee R, Aristizabal O, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy in homozygous myosin-binding protein-C mutant mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1235–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Harris S, Bartley C, Hacker T, McDonald K, Douglas P, Greaser M, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Cardiac Myosin Binding Protein-C Knockout Mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012222.70819.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carrier L, Knoll R, Vignier N, Keller D, Bausero P, Prudhon B, et al. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy in heterozygous cMyBP-C null mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vignier N, Schlossarek S, Fraysse B, Mearini G, Kramer E, Herve P, et al. Nonsense-Mdediated mRNA Decay and Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Regulate Cardiac Myosin-Binding protein C Mutant Levels in Cardiomyopathic Mice. Circ Res. 2009;105:239–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cheng Y, Wan X, McElfresh T, Chen X, Gresham K, Rosenbaum D, et al. Impaired contractile function due to decreased cardiac myosin binding protein C content in the sarcomere. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H52–H65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00929.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Barefield D, Kumar M, de Tombe PP, Sadayappan S. Contractile dysfunction in a mouse model expressing a heterozygous MYBPC3 mutation associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H807–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00913.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuster DW, Sadayappan S. MYBPC3’s alternate ending: consequences and therapeutic implications of a highly prevalent 25 bp deletion mutation. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 2014;466:207–13. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Christodoulou DC, Wakimoto H, Onoue K, Eminaga S, Gorham JM, DePalma SR, et al. 5′RNA-Seq identifies Fhl1 as a genetic modifier in cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1364–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI70108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dorn GW, 2nd, McNally EM. Two strikes and you’re out: gene-gene mutation interactions in HCM. Circ Res. 2014;115:208–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Blankenburg R, Hackert K, Wurster S, Deenen R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, et al. beta-Myosin heavy chain variant Val606Met causes very mild hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice, but exacerbates HCM phenotypes in mice carrying other HCM mutations. Circ Res. 2014;115:227–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Najafi A, Schlossarek S, van Deel ED, van den Heuvel N, Guclu A, Goebel M, et al. Sexual dimorphic response to exercise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated MYBPC3-targeted knock-in mice. Pflugers Arch. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1570-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00424-014-1570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Berul CI, McConnell BK, Wakimoto H, Moskowitz IP, Maguire CT, Semsarian C, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia vulnerability in cardiomyopathic mice with homozygous mutant Myosin-binding protein C gene. Circulation. 2001;104:2734–9. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McConnell BK, Fatkin D, Semsarian C, Jones KA, Georgakopoulos D, Maguire CT, et al. Comparison of two murine models of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2001;88:383–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McConnell B, Fatkin D, Semsarian C, Jones K, Georgakopoulous D, Maguire C, et al. Comparison of Two Murine Models of Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2001;88:383–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Verma SK, Krishnamurthy P, Barefield D, Singh N, Gupta R, Lambers E, et al. Interleukin-10 treatment attenuates pressure overload-induced hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circulation. 2012;126:418–29. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pfaffl M. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2002–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Christodoulou DC, Gorham JM, Herman DS, Seidman JG. Construction of normalized RNA-seq libraries for next-generation sequencing using the crab duplex-specific nuclease. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0412s94. Chapter 4:Unit4 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Martin LA, Hahn HS, Dorn GW, 2nd, et al. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2005;97:1156–63. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190605.79013.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barefield D, Sadayappan S. Phosphorylation and function of cardiac myosin binding protein-C in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:866–75. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sadayappan S, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Lorenz JN, Sargent M, Molkentin JD, et al. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation is cardioprotective. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16918–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607069103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Barefield D, Cuello F, Avkiran M, et al. A critical function for Ser-282 in cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2011;109:141–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Copeland O, Sadayappan S, Messer AE, Steinen GJ, van der Velden J, Marston SB. Analysis of cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation in human heart muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:1003–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chandra M, Dong WJ, Pan BS, Cheung HC, Solaro RJ. Effects of protein kinase A phosphorylation on signaling between cardiac troponin I and the N-terminal domain of cardiac troponin C. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13305–11. doi: 10.1021/bi9710129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Frazier AH, Ramirez-Correa GA, Murphy AM. Molecular mechanisms of sarcomere dysfunction in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;31:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tong C, Stelzer J, Greaser M, Powers P, Moss R. Acceleration of crossbridge kinetics by protein kinase A phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein C modulates cardiac function. Circ Res. 2008;103:974–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chen P, Patel J, Powers P, Fitzsumons D, Moss R. Dissociation of Structural and Functional Phenotypes in Cardiac Myosin-Binding Protein C Conditional Knockout Mice. Circulation. 2012;126:1194–205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fraysse B, Weinberger F, Bardswell S, Cuello F, Vignier N, Geertz B, et al. Increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and diastolic dysfunction as early consequences of Mybpc3 mutation in heterozygous knock-in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mearini G, Schlossarek S, Willis M, Carrier L. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac dysfunction. Biochim Biophys. 2008;1782:749–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sorajja P, Elliott PM, McKenna WJ. The molecular genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prognostic implications. Europace. 2000;2:4–14. doi: 10.1053/eupc.1999.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Witayavanitkul N, Ait Mou Y, Kuster DW, Khairallah RJ, Sarkey J, Govindan S, et al. Myocardial infarction-induced N-terminal fragment of cardiac myosin-binding protein C (cMyBP-C) impairs myofilament function in human myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:8818–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jeong EM, Monasky MM, Gu L, Taglieri DM, Patel BG, Liu H, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves diastolic dysfunction by reversing changes in myofilament properties. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;56:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Patel BG, Wilder T, Solaro RJ. Novel control of cardiac myofilament response to calcium by S-glutathionylation at specific sites of myosin binding protein C. Front Physiol. 2013;4:336. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dhandapany PS, Sadayappan S, Xue Y, Powell GT, Rani DS, Nallari P, et al. A common MYBPC3 (cardiac myosin binding protein C) variant associated with cardiomyopathies in South Asia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:187–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Fatkin D, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Genetics and disease of ventricular muscle. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a021063. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.