Abstract

We examined mental health related visits to emergency departments (EDs) among children from 2001 to 2011. We used the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—Emergency Department, 2001–2011 to identify visits of children 6 to 20 years old with a reason-for-visit code or ICD-9-CM diagnosis code reflecting mental health issues. National percentages of total visits, visit counts, and population rates were calculated, overall and by race, age, and sex. ED visits for mental health issues increased from 4.4% of all visits in 2001 to 7.2% in 2011. Counts increased 55,000 visits per year and rates increased from 13.6 visits/1000 population in 2001 to 25.3 visits/1000 in 2011 (p<0.01 for all trends). Black children (all ages) had higher visit rates than white children and 13–20 year olds had higher visit rates than children 6–12 years old (p<0.01 for all comparisons). Differences between groups did not decline over time.

Keywords: Emergency Department, Mental Health, children, trends

Introduction

Concerns have been raised by researchers about lack of capacity in emergency departments (EDs) to appropriately address mental health (MH) problems among children and adolescents, potentially leading to compromised quality of care, and in turn, poor MH outcomes.1 A recent technical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics outlined the current barriers to providing quality MH services to children and adolescents in the ED.2 These included a lack of research on effective ED practice for child and adolescent psychiatric care, need for improved education and training among ED staff, the ED as a sub-optimal setting in which to assess and manage psychiatric patients, a shortage of inpatient pediatric psychiatric beds needed for hospital admission of ED patients, and a scarcity of pediatric psychiatric outpatient services to create adequate follow up for discharged patients.2

Previous studies have shown that between 2%3 and 5%4 of ED visits among children and adolescents less than 19 years of age relate to MH. Trends in MH visits to EDs among children and adolescents in the United States during the 1990’s and up until 2001 have been described.3,5–7 These studies found increases in the number of MH visits, population rates of MH visits, and the percentage of all ED visits that were for MH diagnoses. However, since 2001, national trends in ED visit for MH problems among children and adolescents are unknown.

Further, evidence suggests that children and adolescents from minority populations have less access to needed MH services than those from non-minority populations.8–10 It is unknown whether differences also exist in ED visit rates, and how these might be changing over time.

This study examines trends in MH visits to the ED among 6–20 year old children and adolescents from 2001 to 2011. We examine trends from three perspectives: the percentage of emergency room visits for children and adolescents in this age group that are for MH conditions, the number of visits that are for MH conditions, and the population rate of visits for MH conditions. The first two measures inform the health care system about changes in the needed capacity of the ED to address MH conditions. The third approach may be more valuable to better understand population health needs. Further, we examine the population rates of ED visits for MH conditions by age, race, and sex to determine whether differences exist between these populations.

Methods

This study is a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey-Emergency Department (NHAMCS-ED) from 2001 through 2011. The NHAMCS-ED is a national probability sample survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to estimate characteristics of in-person visits to EDs of nonfederal, short-stay hospitals in the United States with an average stay of < 30 days. The ED’s specialty may be general (medical or surgical) or children’s general. The survey uses a four-stage complex survey design with the four stages made up of geographic primary sampling units (PSUs), hospitals and EDs within PSUs, emergency service areas (ESAs) within EDs, and then patient visits within ESAs. There also is a three stage design specifically for children’s hospitals. Details of the NHAMCS-ED survey can be found elsewhere. 11,12 Unweighted response rates for the survey years ranged from 79.5% in 200713 to 90.8% in 2002.14 The NHAMCS-ED was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board; this study did not require separate institutional review board approval.

Children ages 6 to 20 were selected for this study because of concerns by the authors about the validity of correctly identifying visits requiring psychiatric evaluation in children less than 6 years old. Age 20 was chosen as an upper age limit, as children between 18 and 20 years of age are a group of interest to pediatric ED medical providers (in both pediatric and community hospitals). This is supported both by the American Academy of Pediatrics statement that pediatric responsibility continues to 21 years15 and by previous research that finds that more than half of pediatric ED medical directors (across both pediatric and community hospitals) use age cutoffs of greater than 18 years of age, but only 7% have upper age limits of 21 years or higher.16

Visits to the ED for MH problems were identified that included International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnosis codes or reason-for-visit codes that would reflect a visit likely requiring a psychiatric evaluation during the ED visit. ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis codes represent the physician’s final assessment of the patient’s diagnosis. Reason-for-visit codes, in contrast, are a classification system developed by NCHS to classify patients’ complaints, symptoms, or other reasons for seeking care, as stated in the patient’s own words.13 Patients with any ICD-9-CM codes or reason for visit codes in Table 1 were included as having a MH visit to the ED. The only exception was that observations with a reason-for-visit code of “functional psychoses,” which could include autistic patients, were not included if they also had an ICD-9-CM code indicating a pervasive developmental disorder, including autism. This was to prevent patients from being identified as having a MH visit solely due to a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder.

Table 1.

Inclusions criteria, Reason for Visit and ICD-9 codes included

| Reason for Visit Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 1100.0 | Anxiety and nervousness |

| 1105.0 | Fears and phobias |

| 1110.0 | Depression |

| 1115.0 | Anger |

| 1120.0 | Problems with identity and self-esteem |

| 1125.0 | Restlessness (including hyperactivity, overactivity) |

| 1130.0 | Behavior disturbances |

| 1130.1 | Antisocial behavior |

| 1130.2 | Hostile |

| 1130.3 | Hysterical Behavior |

| 1130.5 | Obsessions and Compulsions |

| 1140.0 | Smoking problems (can’t quit, smoking too much) |

| 1145.0 | Alcohol related problem (alcohol abuse) |

| 1150.0 | Abnormal drug usage (drug abuse) |

| 1155.0 | Delusions or Hallucinations |

| 1160.0 | Psychosexual disorders |

| 1165.0 | Other symptoms or problems relating to psychosocial and mental disorders, NEC |

| 2305.0 (included if no ICD-9-CM code codes for pervasive developmental disorder spectrum condition also present (ICD-9-CM 299.xx)) | Functional Psychoses (includes Autism, bipolar disease, major depression, schizophrenia, paranoid states, and psychoses) |

| 2310.0 | Neuroses |

| 2315.0 | Personality and character disorder |

| 2320.0 | Alcoholism |

| 2321.0 | Drug Dependence |

| 2330.0 | Other and unspecified mental disorders |

| 3130.0 | General psychiatric or psychological examination |

| 4410.0 | Psychotherapy |

| 4705.0 | Marital problems |

| 4710.0 | Parent-child problems |

| 4715.0 | Other problems of family relationships |

| 4730.0 | Social adjustment problems |

| 5818.0 | Intentional self-mutilation |

| 5820.0 | Suicide attempt |

| 5820.1 | Intentional overdose |

| 5910.0 | Adverse effect of drug abuse (unintentional overdose) |

| ICD-9 Codes | Description |

| 291.xx | Alcohol induced mental disorders |

| 292.xx | Drug induced mental disorders |

| 295.xx | Schizophrenia |

| 296.xx | Episodic Mood disorders |

| 297.xx | Delusional Disorders |

| 298.xx | Other non-organic psychoses |

| 300.xx | Anxiety, dissociative, and somatoform disorders |

| 301.xx | Personality disorders |

| 302.xx | Sexual and gender identity disorders |

| 303.xx | Alcoholic dependence syndrome |

| 304.xx | Drug dependence |

| 305.xx | Nondependent abuse of drugs (includes Tobacco dependence) |

| 306.xx | Physiological malfunction arising from mental factors |

| 307.1 | Anorexia Nervosa |

| 307.2x | Tic disorders including Tourettes |

| 307.3 | Stereotypic movement disorders |

| 307.4 | Specific disorders of sleep of non-organic origin |

| 307.5 | Other and unspecified eating disorders |

| 307.6 | Enuresis of nonorganic origin |

| 307.7 | Encopresis of nonorganic origin |

| 307.80 | Psychogenic pain, site unspecified |

| 307.89 | Other pain disorder related to psychological factors |

| 308.xx | Acute reaction to stress |

| 309.xx | Adjustment reaction |

| 311.xx | Depressive disorder, not elsewhere classified |

| 312.xx | Disturbance of conduct, not elsewhere classified |

| 313.xx | Disturbances of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence |

| 314.xx | Hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood (includes ADHD with and without hyperactivity) |

| V61.0–V61.2 | Family disruption, Counseling for marital and partner problems (including spousal abuse), Parent-child problems |

| V62.84 | Suicidal ideation |

| V65.42 | Counseling on substance use and abuse |

| V70.1 | General psychiatric exam requested by the authority |

| V70.2 | General psychiatric exam, other and unspecified |

| V71.0x | Observation for suspected mental condition |

For each year, among all children ages 6 to 20 years of age (n=65,400), estimates were made of both the number of MH visits, and the percentage of all visits that were for a MH condition. Estimates were created overall and by age, sex, and race. Sample weights were used to create nationally representative estimates. STATA 12.1 SE was used for these analyses and to account for the complex sample design of the surveys. Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or were based on fewer than 30 observations were considered statistically unreliable. Population rates were created by dividing the estimate of the number of visits (and its associated standard error) by the US civilian noninstitutional population of children 6 to 20 years of age. These estimates were obtained from special Census-2000 based postcensal tabulations provided to NCHS by the U.S. Census Bureau, from July 1st state population estimates for each year, by age, sex, and race.

To assess trends over time, yearly estimates for visit numbers, percentage of all visits, and visit rates, as well as associated standard errors, were entered as dependent variables into three separate Joinpoint regressions, each with year as the independent variable. Joinpoint regressions were conducted in Joinpoint v.3.5.1, which fits the simplest linear model with no changes in trend (a straight line) and, using a series of Monte Carlo permutation tests, tests whether 1 or more joinpoints (changes in linear trend) are statistically significant and should be added to the model.17 Both linear and log-linear (log of dependent variable) models were used for percentage of all visits and visit rates to identify the percentage point change per year and the annual average percent change. No joinpoints were identified during the observation years for any of the trends examined in this study, so linear and log trends across the entire observation period are reported. Results yielding p-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Trends in population rates were examined by race, using black and white as groupings. Hispanic ethnicity and other minority groups were not included because sample sizes were not sufficient and because yearly population estimates that included Hispanic ethnicity were not available before 2006. Race was missing in approximately 13% of all visits to the ED among children 6–20 years of age and these values were imputed by NCHS. Trends were also examined by age, using 6–12, 13–17, and 18–20 as age groupings, and by sex. Joinpoint was used to examine whether trend lines varied by race, age, and sex. First, Joinpoint was used to test whether two trend lines are coincident (identical) or different from one another. 17 Coincidence of two lines indicates that both the slope and intercept of the lines were the same as one another. If subgroup trends were coincident, only combined results were reported. If the subgroup trend lines were different from one another, Joinpoint was then used to see if the slopes of the subgroups trend lines were parallel to one another.17 If slopes were parallel, then combined slopes were tested to determine whether trends over time were increasing, decreasing, or neither. If slopes were not parallel to one another, each was tested to determine its directionality.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the overall trends in the percentage of visits, number of visits, and visit rates by varying the definition of visits for MH conditions to the ED. First, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was included in the main analysis, as psychiatric evaluation of patients resulting in this diagnosis may occur in the ED. However, because other research suggests increased diagnoses of ADHD during these years,18 we considered definitions that did not include either ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes or the reason-for-visit code for ADHD to determine whether changes might be due to secondary diagnoses of ADHD. Second, to assure that trends did not represent variation in non-MH related visits by children and adolescents with MH conditions, we considered definitions that included only observations that included a reason-for-visit code indicative of a MH condition. Third, to assure that trends did not represent changes in concern for MH conditions, but without changes in true MH diagnoses, we considered only observations that included an ICD-9-CM code indicative of a MH condition.

Results

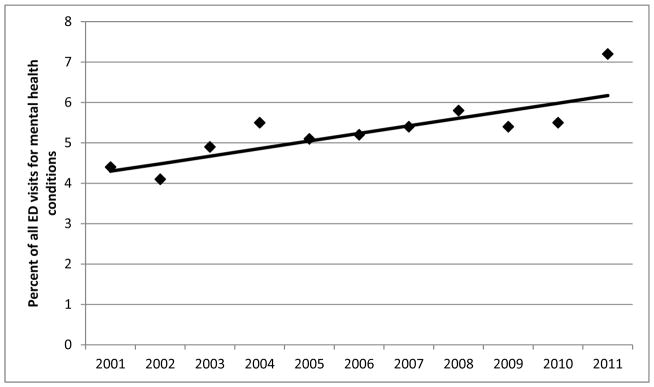

The percent of ED visits that were for MH conditions among children and adolescents 6 to 20 years of age increased from 4.4% of all ED visits in 2001 to 7.2% in 2011 (Table 2), an increase of 0.19 percentage points (SE: 0.04) per year (p<0.01) (Figure 1). Log-linear regression indicated that this was an average annual percent increase of 3.8% per year (p<0.01). After removing diagnosis and reason-for-visit codes for ADHD, the percentage of ED visits for MH conditions increased 0.18 percentage points per year (SE: 0.36; p<0.001). Using only observations that included reason-for-visit codes indicating MH conditions, the percentage of ED visits for MH conditions increased 0.14 percent per year (SE: 0.03; p<0.001). Including only observations with an ICD-9-CM code for MH conditions, the percentage of ED visits for MH conditions increased 0.16 percent per year (SE: 0.03; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Number of visits, percentage of all visits, and population rates of visits to Emergency departments among children 6 to 20 years of age

| Year | n | Number of Visits | Standard Error | Percentage of all ED visits | Standard Error | Visits per 1000 population | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 338 | 832,000 | 76,000 | 4.4 | 0.35 | 13.6 | 1.24 |

| 2002 | 350 | 784,000 | 70,000 | 4.1 | 0.32 | 12.8 | 1.14 |

| 2003 | 434 | 967,000 | 82,000 | 4.9 | 0.38 | 15.81 | 1.34 |

| 2004 | 406 | 1,069,000 | 117,000 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 17.46 | 1.92 |

| 2005 | 373 | 1,033,000 | 130,000 | 5.1 | 0.59 | 16.87 | 2.12 |

| 2006 | 396 | 1,008,000 | 95,000 | 5.2 | 0.41 | 16.44 | 1.55 |

| 2007 | 335 | 1,062,000 | 112,000 | 5.4 | 0.43 | 17.31 | 1.82 |

| 2008 | 351 | 1,189,000 | 108,000 | 5.8 | 0.47 | 19.39 | 1.76 |

| 2009 | 374 | 1,260,000 | 127,000 | 5.4 | 0.44 | 20.38 | 2.06 |

| 2010 | 399 | 1,215,000 | 105,000 | 5.5 | 0.39 | 19.60 | 1.69 |

| 2011 | 361 | 1,590,000 | 163,000 | 7.2 | 0.56 | 25.33 | 2.60 |

NOTE: Visit counts and standard errors are rounded to the 1000’s.

Figure 1.

Percent of all Emergency Department visits for mental health conditions among children and adolescents, 6 to 20 years of age, 2001–2011

Number of visits also increased from 832,000 in 2001 to 1,590,000 visits in 2011, an average increase of approximately 55,000 visits per year (p<0.0001). After removing diagnosis and reason-for-visit codes for ADHD, there was an average increase of approximately 51,000 visits per year (SE: 8,000; p<0.001). Using only observations that included reason-for-visit codes indicating MH conditions, there was an average increase of 36,000 visits per year (SE: 9,000; p<0.01). Including only observations with an ICD-9-CM code for MH conditions, there was an average increase of 45,000 visits per year (SE: 8,000; p<0.001).

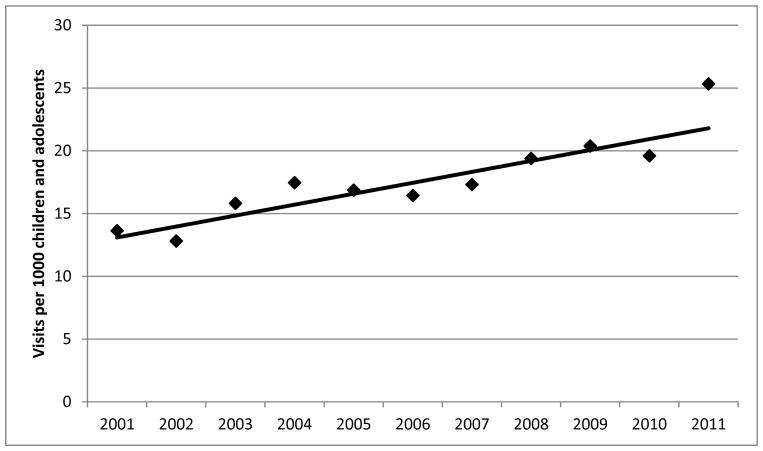

Visit rates per 1000 children and adolescents increased from 13.6 visits/1000 children and adolescents in 2001 to 25.3 visits/1000 in 2011, an increase of 0.9 visits/1000 per year (p<0.0001) (Figure 2). Log-linear regression indicated that this was an average annual percent increase of 5.3% per year (CI: 3.7–7.0, p<0.001). After removing diagnosis and reason-for-visit codes for ADHD, the increase in the rate was 0.81/1000 per year (SE: 0.12; p<0.001). Using only observations that included reason-for-visit codes indicating MH conditions, the increase in the rate was 0.57/1000 per year (SE: 00.14; p<0.01). Including only observations with an ICD-9-CM code for MH conditions, the increase in the rate was 0.7/1000 per year (SE: 0.12; p<0.001)

Figure 2.

Emergency department visits for mental health conditions per 1000 population of children and adolescents 6 to 20 years of age, 2001 to 2011.

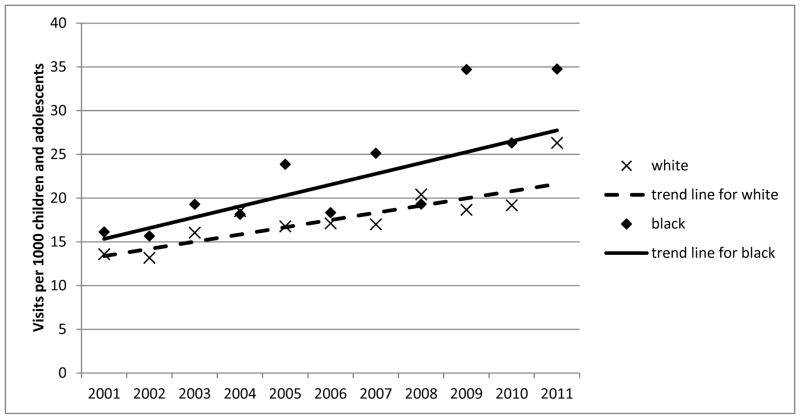

The trend line for ED visit rates for black children and adolescents was not coincident with trend line for white children and adolescents (p<0.01 for test of trend lines being coincident) (Figure 3). No difference was found between the slopes of the trend lines for black children (1.24/1000 per year [SE: 0.3]) and white children (0.82/1000 per year [SE: 0.15]) (p>0.05 for comparison between slopes), although this result should be taken with caution due to smaller sample sizes for black children and adolescents. The combined trend for both black and white children and adolescents together increased over the study period an average of 0.9 visits/1000 children and adolescents per year (p<0.0001). Rates in black children and adolescents were higher than for white children and reached 34.76 visits/1000 in 2011.

Figure 3.

Emergency department visits for mental health conditions per 1000 population of children and adolescents 6 to 20 years of age, 2001 to 2011, by race.

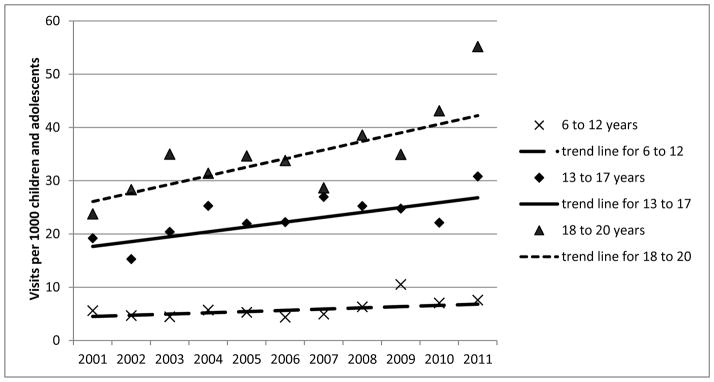

Children 6–12 years of age accounted for 15.7% (SE: 0.1) of the visits for MH conditions across all years (2001–2011), while adolescents 13–17 and 18–20 accounted for 44.1% (SE:0.1) and 40.2% (SE: 0.1) of the visits for MH conditions respectively. Trend lines for each age group were not coincident with any other age groups (p<0.001 for all pairwise comparisons for coincidence of trend lines) (Figure 4). No statistical difference was found between the slopes of the trend lines among children aged 6–12 years (slope = 0.23/1000 per year, (SE: 0.12)), 13–17 years (slope = 0.91/1000 per year (SE: 0.27)), and 18–20 years (slope = 1.61/1000 per year (SE: 0.45)), although this result should be taken with caution due to limited statistical power. The combined trend across all age groups increased over the study period an average of 0.9 visits/1000 children and adolescents per year (p<0.0001). Younger children, 6–12 years of age, had the lowest rates of ED visits for MH conditions, adolescents 13–17 had the next lowest rates, and 18–20 year-olds had the highest rates, reaching 55.18/1000 in 2011.

Figure 4.

Emergency department visits for mental health conditions per 1000 population of children and adolescents 6 to 20 years of age, 2001 to 2011, by age (6 to 12 years, 13 to 17 years, and 18 to 20 years).

Rates of ED visits for MH conditions did not statistically differ by sex (p>0.05 for test of coincidence of trend lines).

Discussion

Between 2001 and 2011, visits for MH conditions to the ED among children and adolescents increased in terms of the number of ED visits, the rate of visits per population, and the percent of visits to EDs in this age group. In addition, black children and adolescents had a higher rate of ED visits than white children and adolescents, while adolescents 18–20 had a higher rate of ED visits than adolescents 13–17, who in turn had higher rates of visits than children 6–12 years of age.

The continuation during the last decade of increasing ED visits for MH conditions among children and adolescents has several implications. Concerns have been raised by public health researchers 1,2,19,20 that increased utilization of the ED for MH conditions among children and adolescents may reflect gaps in the MH infrastructure of the US. At the same time, an Institute of Medicine report on emergency care suggested that care for MH conditions received by children and adolescents in the ED may be substandard, and there may be shortcomings in training and availability of ED staff necessary to address MH issues.21 Although the increases in visits identified in this study cannot directly address whether outpatient MH care has improved, or the quality of care received during these visits, it does suggest that greater resources are currently necessary to adequately address MH issues in the ED than were needed in previous decades.

Differences in rates by race are of interest, given concerns about access to MH care for minority youth in the US.2,8–10,22 Also, although we were not able to identify a difference in the rate of increase between black and white children and adolescents, a lack of statistical power may have prevented us from seeing such a difference if it was present. However, given the higher point estimate in the rate of increase among black compared to white children and adolescents (1.24/1000 per year vs. 0.82/1000 per year), it is clear that the difference in rates did not decline over the study period. The causes of the persistent gap between black and white children and adolescents in the population rate of ED visits are unclear, and causes may be multifactorial.

Comparisons to previous research need to account for differences in age groups examined. Previous research examining trends in MH ED visits among children and adolescents have often used an upper age limit of < 19 years.3,5 Inclusion of adolescents 18–20 years of age in our study, for whom rates of ED visits for MH conditions are higher than younger age groups, increases all three measures: the percent of all ED cases, the number of visits, and the rate of visits that are for MH conditions. For example, in 2011, the rate of visits to the ED per 1000 children and adolescents was only 17.4 (SE: 2.1)/1000 among children and adolescents 6–17, while among the age group of 6–20, it was 25.3 (SE: 2.6)/1000. This should be considered when comparing to other research.

Strengths and Limitations

Like all studies, this study has limitations. First, defining a MH visit to the ED is challenging. In this study, we chose to identify cases that would likely require psychiatric evaluation. However, other researchers have used broader definitions. For example, Grupp-Phelan, et. al. include in their definition of MH visits to the ED, in addition to visits with reason-for-visit codes and ICD-9-CM codes representing MH conditions, visits at which psychotropic medications were prescribed or refilled,5 and Sills and Bland used a larger range of ICD-9-CM codes that would include diagnoses of autism, for example. 3 No single definition may be perfect, and as such, we tried various definitions, but obtained largely unchanged results. Also, the sample sizes in this study are not large enough to adequately examine the prevalence of subgroups of MH conditions, as others have done using research networks.23 Further, 13% of observations had missing race/ethnicity and, although race was singly imputed by NCHS, this could affect our analyses of race subgroups. Finally, other important aspects of care surrounding ED visits could not be measured. Nonetheless, this study uses a large, nationally representative data set to examine trends in ED visits for MH conditions among children and adolescents, over a recent period when these trends had not previously been examined.

Conclusion

ED visits for MH issues have increased between 2001 and 2011 among children and adolescents 6–20 year of age in terms of visit numbers, population rates, and percentage of all ED visits in this age group. Population rates were higher for black than white children and adolescents and were higher for adolescents than school-aged children (6 to 12), and these differences have not declined over time.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: No funding or research support was received for this research.

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency Department

- MH

Mental health

- NHAMCS-ED

National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey-Emergency Department

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- PSU

primary sampling units

- ESA

emergency service areas

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision Clinical Modification

- ADHD

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- SE

Standard Error

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

- 1.Cooper JL, Masi R. National Center for Children in Poverty: Columbia University, Mailman School for Public Health. 2007. Child and Youth Emergency Mental Health Care: A National Problem. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan MA, Fein JA Committee on Pediatric Emergency M. Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics. 2011 May;127(5):e1356–1366. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sills MR, Bland SD. Summary statistics for pediatric psychiatric visits to US emergency departments, 1993–1999. Pediatrics. 2002 Oct;110(4):e40. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christodulu KV, Lichenstein R, Weist MD, Shafer ME, Simone M. Psychiatric emergencies in children. Pediatric emergency care. 2002 Aug;18(4):268–270. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency departments. Public health reports. 2007 Jan-Feb;122(1):55–61. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah MV, Amato CS, John AR, Dennis CG. Emergency Department Trends for Pediatric and Pediatric Psychiatric Visits. Pediatric emergency care. 2006;22(9):685–686. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santucci KA, Sather JE, Baker MD. Psychiatry-related Visits to the Pediatric Emergency Department: A Growing Epidemic? Academic Emergency Medicine. 2000;7(5):585. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002 Sep;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougherty D, DeSoto M. [Accessed 10/28, 2013];Fact Sheet: Findings on Children’s Health Care Quality and Disparities. 2010 :10-P006. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqrdr09/children.pdf.

- 10.Sturm R, Ringel JS, Stein BD, Kapur K. Mental Health Care for Youth: Who Gets It? How Much Does it Cost? Who Pays? Where does the Money Go? [Accessed 10/28, 2013];RAND Health: Research Highlights. 2001 http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/2005/RB4541.pdf.

- 11.Magellan Health Services I. Appropriate Use of Psychotropic Drugs in Children and Adolescents: a Clinical Monograph. Important Issues and Evidence-Based Treatments. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008 Aug 6;(7):1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman WK, Ginsburg GS, Goedhart AW. Factor structure of the childhood anxiety sensitivity index. Behaviour research and therapy. 1999 Sep;37(9):903–917. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman WK, Hinshaw SP. The Second Special Issue on Evidence-Based Pyschosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents: a 10-year Update. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;37(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Child and Adolescent Health. Age limits of pediatrics [Reaffirmed October, 2011] Pediatrics. 1988 May;81(5):736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobson JV, Bryce L, Glaeser PW, Losek JD. Age limits and transition of health care in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatric emergency care. 2007 May;23(5):294–297. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000248701.87916.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed 1/24, 2014];Joinpoint Regression Program. 2013 http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- 18.Akinbami LJ, Liu X, Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children aged 5–17 years in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS data brief. 2011 Aug;(70):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulkhern V, Raab B, Potter D. The Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut. 2007. A Rising Tide: Use of Emergency Departments for Mental Health Care for Connecticut’s children. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas LE. Trends and shifting ecologies: Part I. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America. 2003 Oct;12(4):599–611. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(03)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-based emergency care : at the breaking point. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Public Health Service. Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan P, Alpern ER, Grupp-Phelan J, et al. Epidemiology of psychiatric-related visits to emergency departments in a multicenter collaborative research pediatric network. Pediatric emergency care. 2009 Nov;25(11):715–720. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181bec82f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]