Abstract

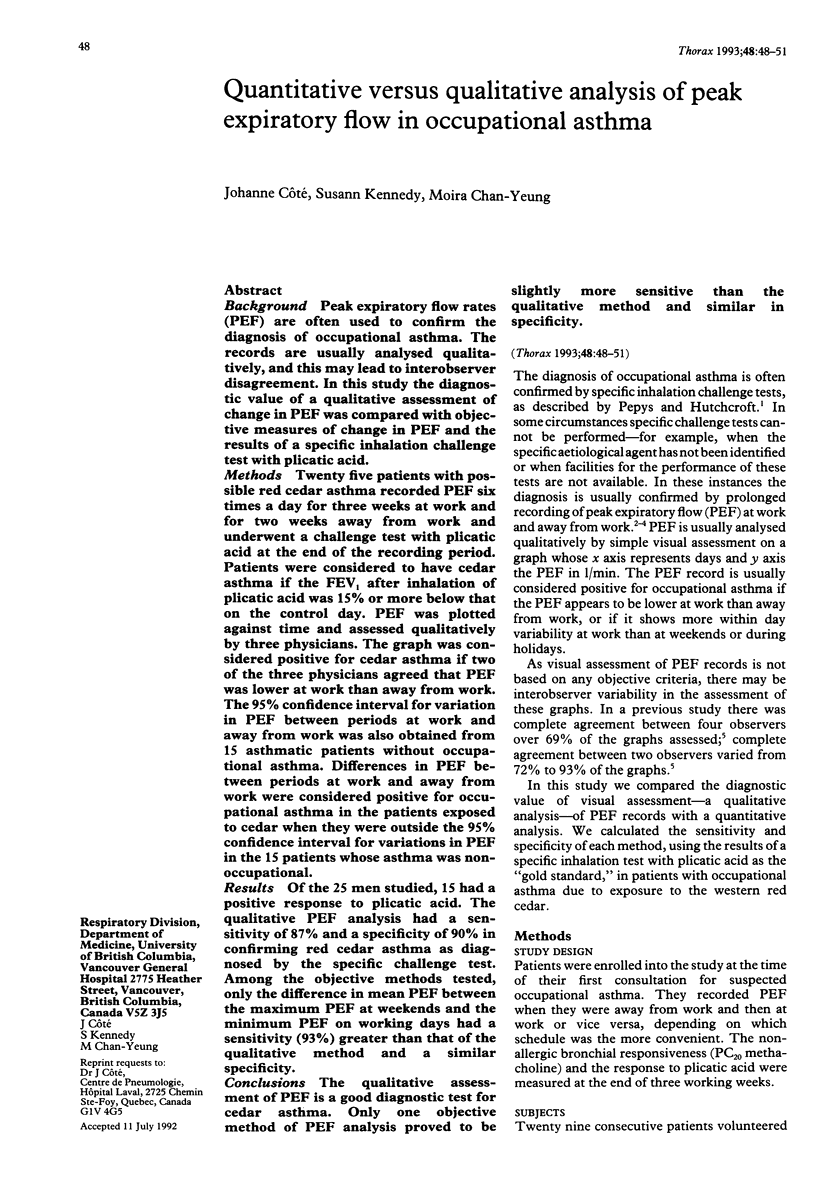

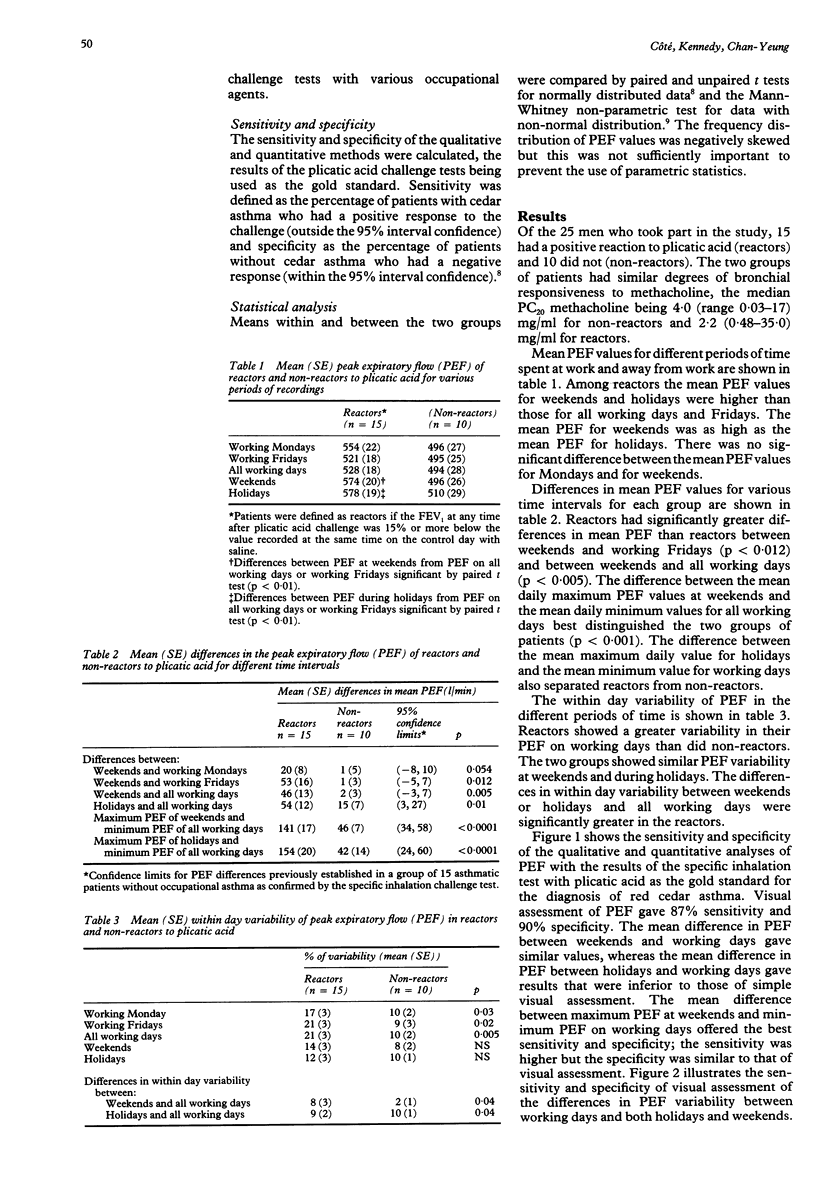

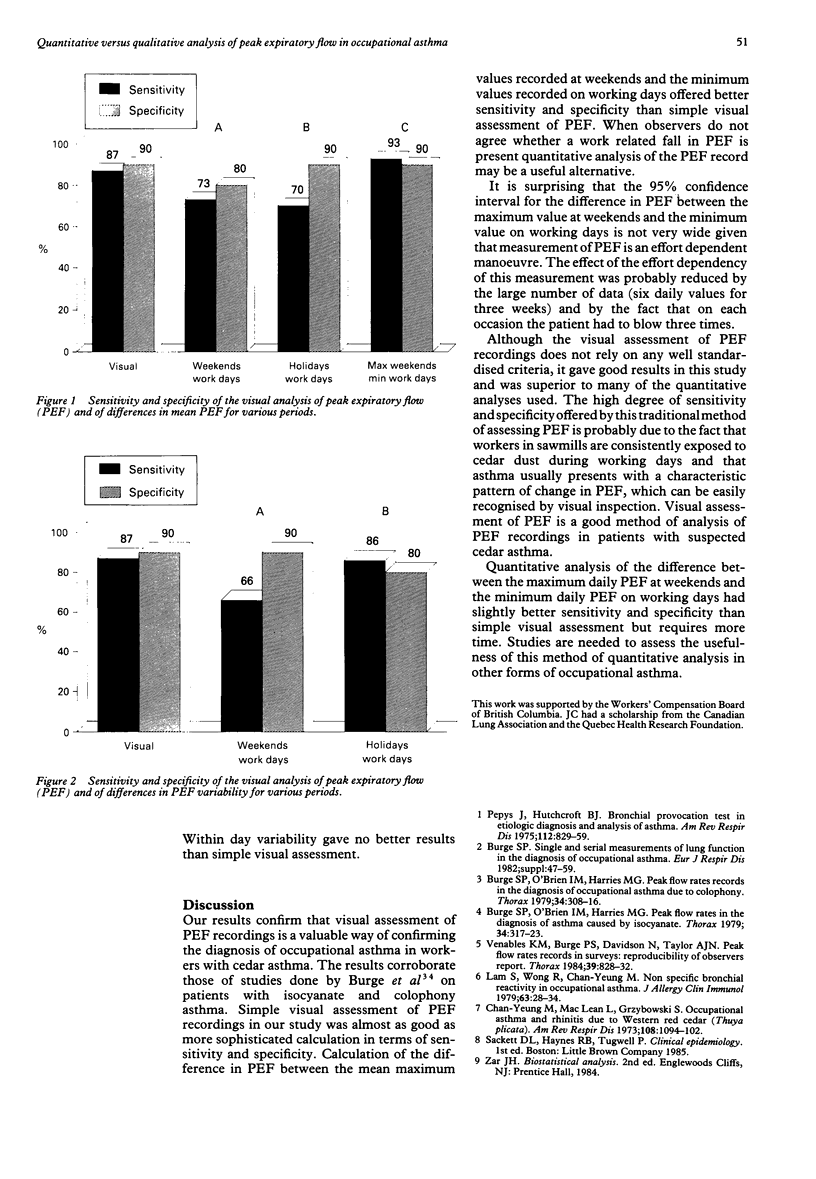

BACKGROUND: Peak expiratory flow rates (PEF) are often used to confirm the diagnosis of occupational asthma. The records are usually analysed qualitatively, and this may lead to interobserver disagreement. In this study the diagnostic value of a qualitative assessment of change in PEF was compared with objective measures of change in PEF and the results of a specific inhalation challenge test with plicatic acid. METHODS: Twenty five patients with possible red cedar asthma recorded PEF six times a day for three weeks at work and for two weeks away from work and underwent a challenge test with plicatic acid at the end of the recording period. Patients were considered to have cedar asthma if the FEV1 after inhalation of plicatic acid was 15% or more below that on the control day. PEF was plotted against time and assessed qualitatively by three physicians. The graph was considered positive for cedar asthma if two of the three physicians agreed that PEF was lower at work than away from work. The 95% confidence interval for variation in PEF between periods at work and away from work was also obtained from 15 asthmatic patients without occupational asthma. Differences in PEF between periods at work and away from work were considered positive for occupational asthma in the patients exposed to cedar when they were outside the 95% confidence interval for variations in PEF in the 15 patients whose asthma was nonoccupational. RESULTS: Of the 25 men studied, 15 had a positive response to plicatic acid. The qualitative PEF analysis had a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 90% in confirming red cedar asthma as diagnosed by the specific challenge test. Among the objective methods tested, only the difference in mean PEF between the maximum PEF at weekends and the minimum PEF on working days had a sensitivity (93%) greater than that of the qualitative method and a similar specificity. CONCLUSIONS: The qualitative assessment of PEF is a good diagnostic test for cedar asthma. Only one objective method of PEF analysis proved to be slightly more sensitive than the qualitative method and similar in specificity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burge P. S., O'Brien I. M., Harries M. G. Peak flow rate records in the diagnosis of occupational asthma due to colophony. Thorax. 1979 Jun;34(3):308–316. doi: 10.1136/thx.34.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge P. S., O'Brien I. M., Harries M. G. Peak flow rate records in the diagnosis of occupational asthma due to isocyanates. Thorax. 1979 Jun;34(3):317–323. doi: 10.1136/thx.34.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge P. S. Single and serial measurements of lung function in the diagnosis of occupational asthma. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;123:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Yeung M., Barton G. M., MacLean L., Grzybowski S. Occupational asthma and rhinitis due to Western red cedar (Thuja plicata). Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973 Nov;108(5):1094–1102. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S., Wong R., Yeung M. Nonspecific bronchial reactivity in occupational asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979 Jan;63(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(79)90158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepys J., Hutchcroft B. J. Bronchial provocation tests in etiologic diagnosis and analysis of asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975 Dec;112(6):829–859. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.112.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables K. M., Burge P. S., Davison A. G., Newman Taylor A. J. Peak flow rate records in surveys: reproducibility of observers' reports. Thorax. 1984 Nov;39(11):828–832. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.11.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]