Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was to identify and summarize evidence of the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal status in children and adolescents. We searched PubMed, Institute for Scientific Information Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Library, and 7 additional databases, following the guidance of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, up to December 2014. Observational studies reporting data on the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal diseases in 2–18-y-old participants were included. An initial search identified 4191 papers; 278 potentially effective studies (k = 0.82) and 16 effective studies (k = 0.83) were included after screening. The mean quality of evidence among the studies was 20.3, according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology checklist (k = 0.79). Meta-analyses showed that obesity (measured by body mass index) was significantly associated with visible plaque index (OR: 4.75; 95% CI: 2.42, 9.34), bleeding on probing (OR: 5.41; 95% CI: 2.75, 10.63), subgingival calculus (OR: 3.07; 95% CI: 1.10, 8.62), probing depth (OR: 14.15; 95% CI: 5.10, 39.25) and flow rate of salivary secretion (standardized mean difference: −0.89; 95% CI: −1.18, −0.61). However, various results were reported in the effective studies that were not included in meta-analyses. In conclusion, obesity is associated with some signs of periodontal disease in children and adolescents. Further studies with a comprehensive prospective cohort design and more potential variables are recommended.

Keywords: anthropometry, oral health, obesity, adolescent, systematic review

Introduction

Periodontal disease has been reported to be one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide (1). According to a recent CDC report, nearly one-half of adults aged ≥30 y had signs of periodontal disease in the United States (2) and a majority of children and adolescents had some form of gingivitis, which may initiate severe periodontal diseases (3).

The bidirectional association between periodontal diseases and systemic health has been widely reported. It is well recognized that type 2 diabetes mellitus (4), preterm birth (5), and cardiovascular diseases (6) are associated with periodontal diseases. Considerable evidence has suggested that tooth loss that might be caused by periodontitis plays an active role in nutrition deficiencies (7–9). Obesity has been proposed to be an independent risk factor for inflammatory periodontal tissue destruction (10) in that both obesity and periodontal diseases share common elevated C-reactive protein concentrations (11) and possible enzymatic mechanisms (12). A number of studies have evaluated the relation between adult periodontitis and adiposity over the last few years (13, 14) and several systematic reviews have been conducted to pool these studies together. Benjamin et al. (15) compiled 57 studies and found higher prevalence of periodontal diseases in obese adults than in the nonobese population. Nineteen studies were included in another meta-analysis in which a positive association between BMI and periodontitis was observed among overweight (OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.51) and obese (OR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.42, 2.30) adults (16). However, clinical and epidemiologic indicators of periodontal status vary considerably between adolescents and adults (17). The results of these studies may not be generalizable to children and adolescents. Relatively few studies focused on the relation between weigh gain and periodontal health (including gingivitis) in children and adolescents before 2010. The systematic review conducted by Katz et al. (18) in 2010 reported inconclusive associations because only few papers were eligible for inclusion. However, more findings have been reported since 2010. There is no doubt that anthropometric measurements are simple, applicable, and economical methods for estimating the nutrition status of children and adolescents. More anthropometric measurements beyond BMI, such as waist circumference (WC)6 (19), weight-to-height ratio, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and triceps skinfold thickness (TRSKF), have been associated with periodontal status since 2010 (20).

Recognition of the relation between periodontal status and anthropometric measurements is of clinical and social importance. The aim of this systematic review was to describe and summarize the evidence regarding the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal health status in children and adolescents.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria.

To investigate the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal diseases in children and adolescents, 10 electronic databases [PubMed, Institute for Scientific Information Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Medical Library, ProQuest Research Library, British Nursing Index, ComDisDome, Gender Watch, and ProQuest Deep Indexing: Medical and Health & Safety Science Abstracts (via ProQuest)] were searched systematically from their commencement to December 2014. Only observational studies (cross-sectional or longitudinal) reported in English were included. The search strategy was composed of MeSH terms of anthropometry and periodontal diseases, as well as relevant MeSH terms in categories (Supplemental Appendix 1). Reference lists of included papers and relevant journals were searched manually.

All participants in the included papers were within the age range of 2–18 y old, according to the definition of “child” (21, 22) and “adolescent” (23), with no restrictions on gender and nationality. Data on the relation between periodontal diseases and anthropometric measurements needed to be accessible. Any biological markers or clinical measurements of periodontal diseases, such as the visible plaque index (VPI), bleeding on probing index (BOP), probing depth (PD), and flow rate of salivary secretion, were considered for analysis. Loss of attachment (LOA), which measured both pocket depth and recession of gingiva, was also included as an important indicator of periodontal diseases. Any measurements involving anthropometry, e.g., height, weight, BMI, WC, WHR, TRSKF, and birth weight, were also extracted.

Data extraction and data analyses.

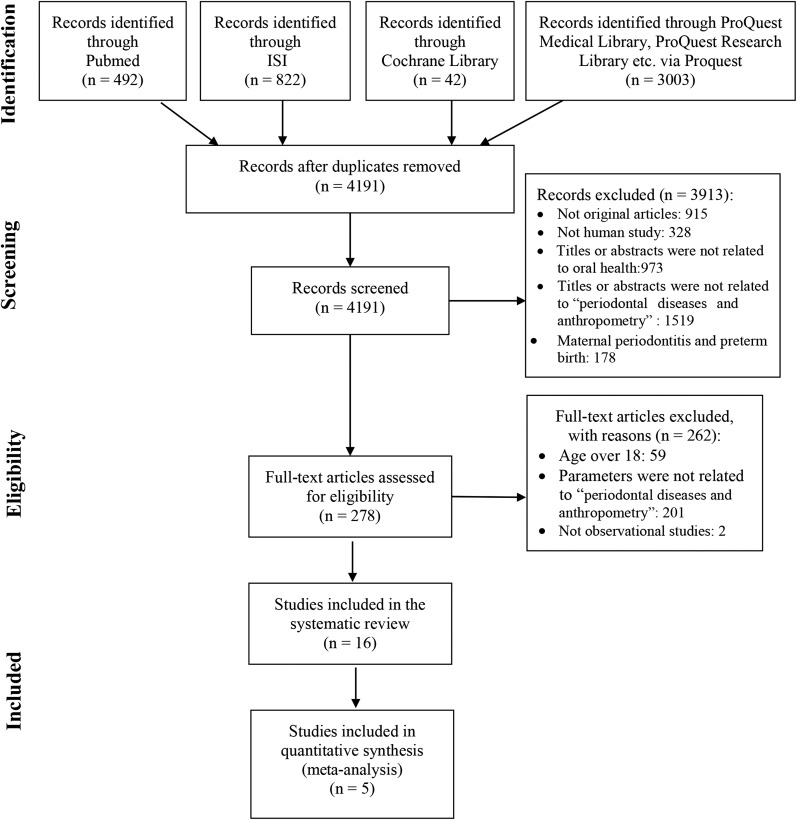

All screening procedures of this systematic review strictly followed the guidance of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (24). The flow diagram of PRISMA is shown in Figure 1. The titles and abstracts of initial papers were independently reviewed by L-WL and LS in the first round of screening. Full texts of the potentially eligible studies were then retrieved and blindly reviewed by the same 2 reviewers in the second round of screening. A third reviewer (HMW) was consulted to resolve discrepant opinions. κ values were calculated to assess inter-reviewer agreement for both rounds of screening (Cohen’s κ).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the search process. ISI, Institute for Scientific Information.

Two reviewers (L-WL and LS) developed the data extraction sheet and performed data extraction. Data extracted included study design, setting, characteristics of participants, periodontal variables, anthropometric assessments, methods for statistical analysis, and confounders adjusted in the model. Two copied extraction sheet were completed independently by these 2 reviewers in order to validate the accuracy of the data extraction. Disagreements were resolved by consensus of the 3 reviewers (HMW, L-WL, and LS).

To summarize the quantitative data, meta-analyses were performed with Stata 12.0 software. Several meta-analyses were conducted to estimate different exposures of periodontal diseases, i.e., “flow rate of salivary secretion,” “participants with VPI >25% sites,” “participants with BOP >25% sites,” “participants with PD >4 mm,” “supragingival calculus,” and “subgingival calculus.” Because data were drawn from different studies and populations, random-effects models were used to allow for heterogeneity in terms of study design and methodology. Forest plots were presented to display the pooled estimates of ORs (Figures 2–6) and standardized mean difference (Figure 7); funnel plots were used to assess publication bias of eligible studies (Supplemental Figures 1–6). The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Values in the text and tables are presented as means ± SEs unless otherwise indicated.

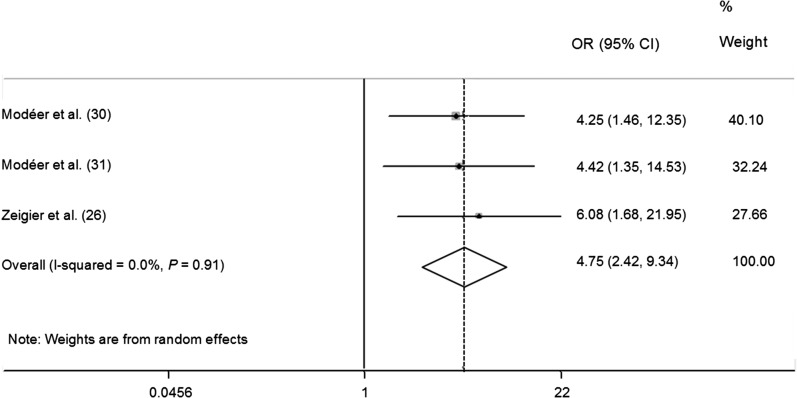

FIGURE 2.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in ORs for having a visible plaque index >25% in obese children and adolescents.

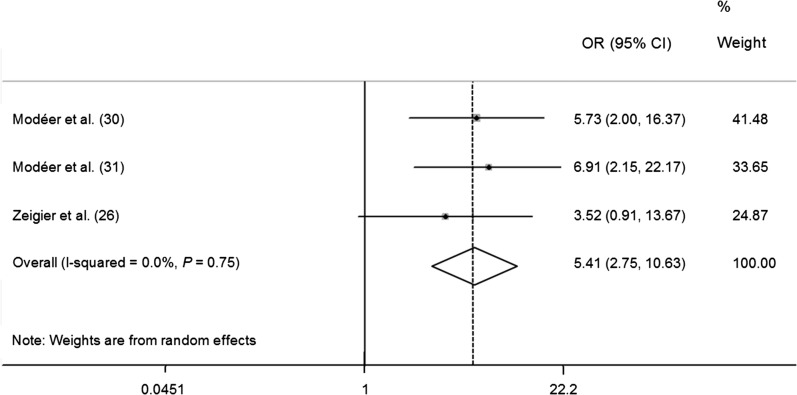

FIGURE 3.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in ORs for having a bleeding on probing score >25% in obese children and adolescents.

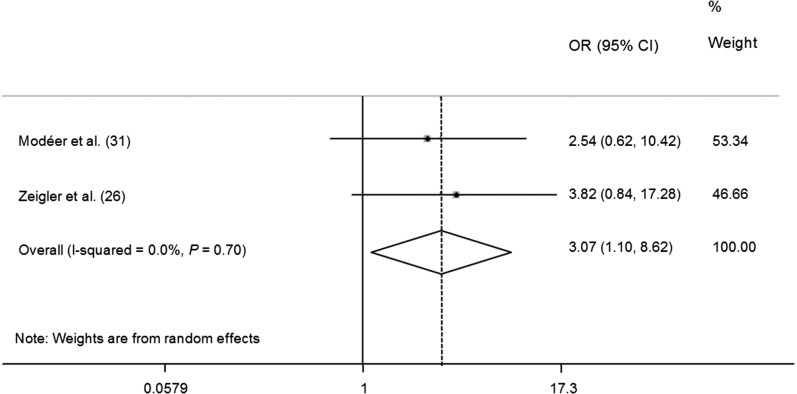

FIGURE 4.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in ORs for having subgingival calculus in obese children and adolescents.

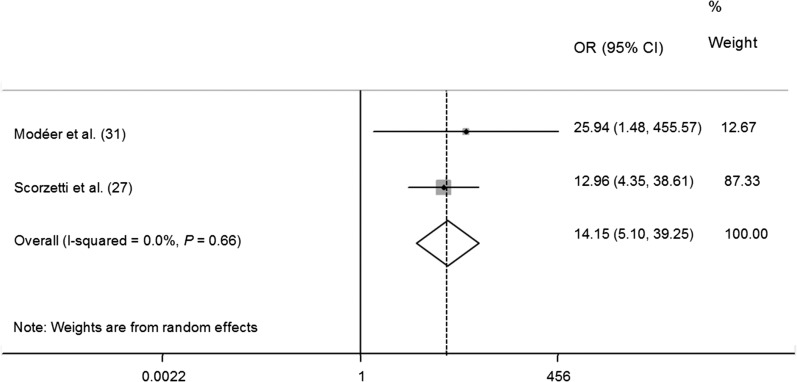

FIGURE 5.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in ORs for having supragingival calculus in obese children and adolescents.

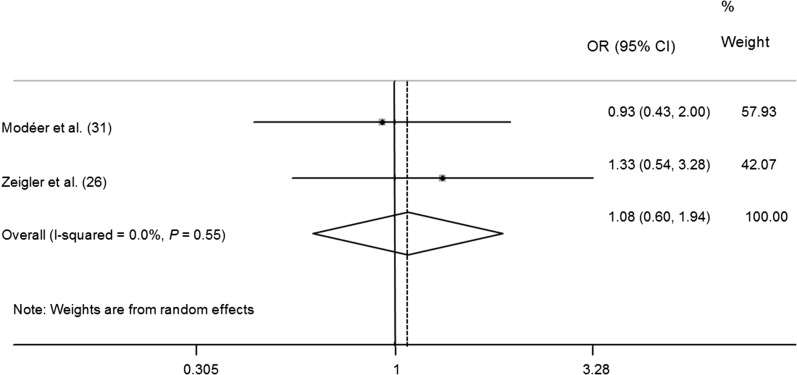

FIGURE 6.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in ORs for having a probing depth >4 mm in obese children and adolescents.

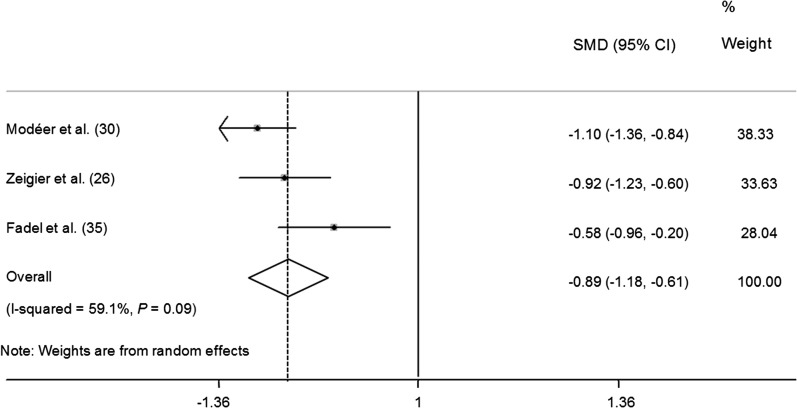

FIGURE 7.

Meta-analysis forest plot presenting differences in mean stimulated salivary secretion for obese compared with normal-weight children and adolescents.

Quality assessment.

The STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (25) was applied to assess the quality of included studies. Thirty-four items, including evaluation of introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other information, were included in the STROBE checklist. Each item used a 4-score scale: “yes” = 1, “incomplete” = 0.5, “no” = 0, “NA” (not applicable) = 0. Each relevant paper scored from 0 to 34. The STROBE checklist was assessed in duplicate by L-WL and LS independently. Inter-reader agreement of the STROBE checklist was assessed by κ value (Cohen’s κ).

Results

A total of 4359 studies were identified from the initial search and 4191 papers were screened after removal of duplicate articles. Two hundred seventy-eight potentially eligible studies were carefully reviewed and 16 effective studies (19, 20, 26–39) ultimately were included in this systematic review. Inter-reviewer agreement was 0.82 ± 0.02 for the first round of screening and 0.83 ± 0.07 for the second round. Descriptive data of included studies are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the included studies on association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal diseases in children and adolescents1

| Author (reference) country | Age; sample size | Study design | Markers of periodontal disease | Markers of anthropometric measurements | Assessment of nutrient/calorie intake | Key findings2 | Confounders |

| Petti et al. (39) 2000 Italy | 17–19 y; 27 cases, 27 controls | Case-control | Presence or absence of gingivitis (defined by BOP) | BMI (adjusted for age and sex) | 3-day food record (daily frequency of meals; fiber intake; mean daily energy intake; and mean daily consumption of total fiber, iron, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin C, and vitamin A) | ● There was no significant difference in overweight/obesity proportion between case and control groups.3 ● Prevalence of marginal deficiencies of thiamin* and riboflavin** was significantly different between case and control groups. ● Riboflavin, calcium and frequency of fiber intake were negatively related to gingivitis.4 |

Age, riboflavin, fiber frequency, calcium |

| Reeves et al. (38) 2006 United States | 13–21 y; 2452 participants | Case-control | Chronic periodontitis (defined by LOA) | Weight; height; waist circumference; triceps; subscapular, suprailiac, and thigh skinfolds; sum of skinfold thickness; and log sum of skinfold thickness | Vitamin intake, calcium intake | ● Young adults (aged 17–21 y) were more likely to have periodontitis with increased weight and waist circumference.4 Weight OR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.09) Waist circumference OR: 1.05 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.08) ● The chance of adolescents (aged 13–16 y) with increased weight and waist circumference was not higher.4 Weight OR: 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.0) Waist circumference OR: 1.0 (95% CI: 0.98, 1.01) |

Calcium intake, sex, race/ethnicity, poverty index ratio, and last dental visit |

| Jamieson et al. (37) 2012 Australia | 18 y; 441 participants | Cohort | Moderate/severe periodontitis (defined by LOA) | Height | Sugar consumption frequency | ● Periodontal disease was positively associated with the shortest tertile (less than 163.1 cm).5* adjusted PR: 1.39 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.82) | Antecedent anthropometric measures, sociodemographics, sugar consumption frequency, and dental behavior variables |

| Modéer et al. (30) 2010 Sweden | 10.3–17.2 y; 65 obese and 65 normal-weight participants | Case-control | VPI%, BOP%, secretion rate of stimulated whole saliva, frequency of tooth-brushing and flossing | BMI (adjusted for age and sex), BMI SDS (obesity, BMI >30 kg/m2; normal weight, BMI <25 kg/m2) | Questionnaire regarding food intake | ● More obese participants had VPI% >25% or BOP% >25% than did controls.3 Number of participants with VPI% >25% obesity vs. control 17/65 vs. 5/65;** Number of participants with BOP% >25% obesity vs. control 21/65 vs. 5/65.*** ● Obese participants had lower mean flow rate of stimulated saliva than did controls.4 Flow rate (mean ± SD) controls vs. obese participants 2.0 ± 0.9 vs. 1.2 ± 0.5 mL/min*** ● 1-u increase in BMI SDS (unadjusted) implied an increase of OR of flow rate (<1.5 mL/min) by 1.36.4 Unadjusted OR: 1.36*** |

Age, gender, chronic diseases, medication, sociodemographic factors, and oral hygiene variables for regression analysis with flow rate of saliva and BMI |

| Modéer et al. (31) 2011 Sweden | 14.5 y (mean); 52 obese and 52 normal-weight participants | Case-control | VPI%, BOP%, PD, calculus, incipient alveolar bone loss, concentrations of adiponectin, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α in GCF | BMI (adjusted for age and sex) (obesity, BMI >30 kg/m2; normal weight, BMI <25 kg/m2) | Questionnaire regarding food intake | ● More obese participants had VPI% >25%, BOP% >25%, PD (>4 mm) or self-perceived daily gingival bleeding than controls.3 Number of participants with VPI% >25% obesity vs. control 14/52 vs. 4/52;** Number of participants with BOP% >25% obesity vs. control 19/52 vs. 4/52;*** Number of participants with PD (>4 mm) obesity vs. control 10/52 vs. 0/52;*** Number of participants with self-perceived daily gingival bleeding obesity vs. control 7/52 vs. 0/52;** ● No significant difference of prevalence for LOA >2 mm (P = 0.540), subgingival calculus (P = 0.183) and supragingival calculus (P = 0.844) was found between obese participants and controls.5 ● Obese participants had higher concentrations of IL-1β***, IL-8 *** in GCF than controls.3 ● The occurrence of PD (>4 mm) was associated with BMI SDS;4 unadjusted OR: 1.63 (95% CI: 1.14, 2.32)** adjusted OR: 1.87 (95% CI: 1.08, 3.26)* |

BOP (>25%), subgingival calculus in regression analysis with the occurrence of PD as dependent variable |

| Zeigler et al. (26) 2011 Sweden | 14.7 y (mean); 29 obese and 58 normal-weight participants | Case-control | VPI%, BOP%, secretion rate of stimulated whole saliva, bacteria from gingival crevice, incipient alveolar bone loss and calculus | BMI (adjusted for age and sex) (obesity, BMI >30 kg/m2; normal weight, BMI <25 kg/m2). | Not mentioned | ● Obesity was associated with VPI% >25% and salivary flow rate.5 VPI >25% obesity vs. control 9/29 vs. 4/583 OR: 6.40 (95% CI: 1.76, 23.20)** Salivary flow rate obesity vs. control (mean ± SD) 1.3 ± 0.6 vs. 2.0 ± 0.9 mL/min3 OR: 0.32 (95% CI: 0.15, 0.70)** ● Obesity was not associated with BOP% >25% (P = 0.069), supragingival calculus (P = 0.537), subgingival calculus (P = 0.082), or Spirochetes (P = 0.713).5 ● Obesity was associated with Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteroides, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacteria.5 Firmicutes OR: 1.10 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.74)** Bacteroidetes OR: 1.23 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.38)** Actinobacteroides OR: 5.22 (95% CI: 2.01, 13.58)** Proteobacteria OR: 1.16 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.27)** Fusobacteria OR: 1.30 (95% CI: 1.12, 1.52)** ● Obesity was associated with sum of bacterial cells;4 unadjusted OR: 1.05 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.07)** adjusted OR: 1.05 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.08)** |

BOP >25%, VPI >25%, no daily tooth brushing—evenings, salivary flow rate (mL/min), and chronic disease in regression analysis with obesity as dependent variable |

| Franchini et al. (34) 2011 Italy | 10–17 y; 98 participants | Case-control | PI, GI | BMI (adjusted for age and sex) (overweight, BMI 25–30 kg/m2; obesity, BMI >30 kg/m2), WC, hip circumference | Not mentioned | ● The overweight/obese group had more PI and GI than the normal-weight group.6 GI (mean ± SD) obesity/overweight vs. normal-weight 1.20 ± 0.42 vs. 0.76 ± 0.50;*** PI (mean ± SD) obesity/overweight vs. normal-weight 1.42 ± 0.61 vs. 0.77 ± 0.49;*** ● PI was significantly affected by gender** and obesity*** status, but not for the combination of the 2.6 ● Overweight/obesity status had no positive correlation with GI (GI >1) and continuous GI.5 |

Age, gender, overweight/obesity status homoeostasis model assessment of the insulin resistance index in regression analysis |

| Nascimento et al. (29) 2013 Brazil | 8–12 y; 1211 participants | Cross-sectional | VPI, gingival bleeding index, presence of dental plaque and gingival bleeding, gingivitis occurrence (analyzed by median according to the previous outcome) | BMI (adjusted for age and sex) | Not mentioned | ● Prevalence of gingivitis was not association with BMI (P = 0.766).3 ● Gingivitis occurrence was not associated with BMI.4 Adjusted OR: 1.03 (95% CI: 0.89, 1.18) (P = 0.659) ● Gingivitis occurrence was associated with BMI in boys.4 Adjusted OR: 1.22 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.48)* ● Gingivitis occurrence was not associated with BMI in girls.4 Adjusted OR: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.78, 1.16) (P = 0.655) |

Sex, age, type of school, household income, maternal schooling, last visit to dentist, frequency of tooth brushing, visible plaque, caries experience, and bleeding during tooth-brushing in regression analysis |

| Scorzetti et al. (27) 2013 Italy | 9.43 ± 2.05 y for cases and 9.67 ± 1.46 y for controls; 44 cases and 60 controls | Case-control | VPI, BOP, PD, CAL | BMI SDS | Not mentioned | ● Obesity was associated with moderate plaque accumulation (presence of visible plaque in 6–12 teeth),** BOP,* and the presence of PD.***3 ● No significant difference between the 2 groups was found for loss of clinical attachment because none of the patients included in this study exhibited CAL ≥3. |

Not applicable |

| Fadel et al. (35) 2013 Sweden | 13–18 y; 27 obese and 28 normal-weight participants | Case-control | Number of marginal gingival bleeding sites, plaque-harboring sites, PD sites, BOP sites. cytokines/adipo -kines in GCF, plaque pH, secretory IgA, counts of salivary mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, alveolar bone level, secretion rate of saliva | BMI (IOTF criteria), WC, WHR | Dietary assessment score | ● There was no difference in dietary assessment score between case group and control group. ● The obesity group had a lower stimulated salivary secretion rate and higher secretory IgA concentrations than controls.7 Secretion rate (mean ± SD) obesity vs. controls 1.55 ± 0.63 vs. 2.05 ± 1.05* adjusted R2 = 0.19;* secretory IgA (mean ± SD) obesity vs. controls 59.5 ± 28.8 vs. 31.8 ± 18.5*** adjusted R2 = 0.38* ● The obesity group had more marginal bleeding sites and BOP sites than control. Marginal bleeding sites (mean ± SD) obesity vs. controls 37 ± 10 vs. 28 ± 12*** BOP sites (mean ± SD) obesity vs. controls 61 ± 22 vs. 43 ± 21** adjusted R2 = 0.38.* ● No difference in unstimulated salivary secretion, plaque-harboring sites, and PD was found between obesity group and control group.7 |

Smoking, age, gender, and medication in multiple linear regression analysis of a selected number of salivary and oral clinical markers |

| Peng et al. (20) 2014 Hong Kong | 5 y; 324 participants | Cross-sectional | VPI | Body height; body weight; W:H, BMI, WC, WHR, and TRSKF z scores | Not mentioned | ● No association was found between W:H, BMI, WC, WHR, and TRSKF z scores and VPI.4 ● WHR z score and WC z score were associated with high VPI [VPI score ≥ median value (65%)] before being adjusted for sociodemographic status4 but not associated after adjustment.4 WHR z score unadjusted OR: 1.28 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.61)* adjusted OR: 1.09 (95% CI: 0.86, 1.37) WC z score unadjusted OR: 1.25 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.58)* adjusted OR: 1.15 (95% CI: 0.90, 1.46) |

Parent’s education attainment and household monthly income in logistic regression models of associations between VPI proportion and obesity |

| Irigoyen-Camacho et al. (33) 2014 Mexico | 15 y; 257 participants | Cross-sectional | Simplified detritus index, CPI, BOP, LOA | BMI (IOTF), BF% | Not mentioned | ● Overweight and obese were associated with CPI = 1 (OR: 1.20 **) and CPI = 2 (OR: 1.41 **) (both using CPI = 0 as reference group).8 ● CPI ≥2 was associated with BF%.8 Adjusted OR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.07)**. ● Overweight/obesity was associated with CPI = 1.8 Adjusted OR: 1.54 (95% CI: 1.45, 1.63).** ● Overweight/obesity was associated with CPI ≥2.8 Adjusted OR: 1.78 (95% CI: 1.51, 2.10).** ● Overweight/obesity was associated with CPI = 1.8 Adjusted OR: 7.07 (95% CI: 2.74, 18.24).** ● Overweight/obesity was associated with CPI ≥2.8 Adjusted OR: 5.56 (95% CI: 5.39, 5.74) **. |

Sex, school type, simplified detritus index, and tobacco use in regression analysis |

| Brogårdh-Roth et al. (36) 2011 Sweden | 10–12 y; 82 preterm and 82 full-term children | Case-control | VPI%, BOP%, gingivitis (% of total number of surfaces) | Mean gestational age (weeks) and mean birth weight (grams) | Dietary habits | ● There was no significant difference in dietary habits between PT and control. ● PT had more plaque and a higher degree of gingival inflammation.7 VPI (% ± SD) PT vs. control 64.41 ± 16.66 vs. 54.77 ± 18.91;** Gingivitis (% ± SD) PT vs. control 32.71 ± 9.08 vs. 24.51 ± 8.00*** ● EPT had a higher VPI than VPT.7 VPI (%) EPT vs. VPT 72.2 vs. 61.9* ● Preterm twins had a higher VPI than singletons.7 VPI (%) twins vs. singletons 67.4 vs. 59.2* ● Preterm boys had a higher VPI than preterm girls.7 VPI (%) boys vs. girls 67.9 vs. 60.7 (P = 0.050) ● For gingivitis, there were no significant differences between VPT and EPT between twins and singletons or between the sexes.7 |

Not applicable (Student’s t test) |

| Rythén et al. (28) 2012 Sweden | 12.3–16.4 y; 40 EPT in clinical study and 45 in retrospective study, 40/45 controls | Case-control | Salivary secretion, pH, plaque (none/local/general), BOP, PD >4 mm, | Mean gestational age (weeks) and mean birth weight (grams) | Not mentioned | ● The EPT had lower salivary secretion than did controls.3 EPT vs. controls (≥1 mL/min) 20/40 vs. 33/40** ● The EPT had a higher prevalence of plaque than did controls.3 EPT vs. controls (no plaque) 7/40 vs. 19/40** ● The EPT had a higher prevalence of BOP than did controls.3 EPT vs. controls 16/40 vs. 7/40** ● The EPT had more BOP sites than did controls (Mann-Whitney = 521.5).*9 ● No significant difference in the number of children with PD (≥4 mm) was found between EPT and controls.3 ● No significant difference in the frequency of PD (≥4 mm) was found between EPT and controls.9 |

Not applicable |

| Kâ et al. (19) 2013 Canada | 8–10 y; 448 children (with a family history of obesity) | Cross-sectional | TNF-α in GCF, gingival bleeding | WC | HDL cholesterol, TGs | ● Boys with low HDL cholesterol* or high TGs** had higher mean GCF TNF-α than did those without. ● There was no association between the extent of gingival bleeding and HDL cholesterol or TGs in boys or girls. ● Boys with abdominal obesity (WC ≥90th age- and sex-specific percentile) had significantly higher mean GCF TNF-α than did those without abdominal obesity.** ● There was no difference in mean GCF TNF-α between girls with abdominal obesity and those without. ● Among boys, for every 1-u increase in WC, the GCF TNF-α increased by 0.6%.*4 ● There was no association between GCF TNF-α and WC in girls.4 ● WC was not associated with the extent of gingival bleeding.4 |

Age, Tanner stage, family income, parent education, and metabolic syndrome status of the child’s mother in multiple linear regression analyses of association of metabolic syndrome and its components with the extent of gingival bleeding stratified by sex |

| Lalla et al. (32) 2007 United States | 6–18 y; 350 children with diabetes | Cross-sectional | PI, GI, PD, CAL | BMI-for-age percentile (CDC criteria) | BMI-for-age–based nutritional status indicator | ● BMI-for-age percentile (6–11-y-old subgroup, 12–18-y-old subgroup and both of them) was not associated with periodontitis (at least 2 teeth with attachment loss and bleeding).4 ● BMI-for-age percentile (6–11-y-old subgroup, 12–18-y-old subgroup and both of them) was not associated with having at least 2 teeth with bleeding.4 ● BMI-for-age percentile (12–18-y-old subgroup and all-age group) was associated with having at least 2 teeth with attachment loss.4 12–18-y-old adjusted OR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.11)** All-age adjusted OR: 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.04)** ● BMI-for-age percentile (6–11-y-old subgroup) was not associated with having at least 2 teeth with attachment loss.4 |

Age, gender, ethnicity, reported frequency of dental visits, PI, and dental examiner in logistic regression models for having at least 2 teeth with attachment loss/bleeding |

BF, body fat; BOP, bleeding on probing index; CAL, clinical attachment level; CPI, Community Periodontal Index; EPT, extremely preterm children; GCF, gingival cervical fluid; GI, gingival index; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force; LOA, loss of attachment; PD, probing depth; PI, plaque index; PR, prevalence ratio; PT, preterm children; SDS, standard deviation score; TRSKF, triceps skinfold thickness; VPI, visible plaque index; VPT, very preterm children; WC, waist circumference; W:H, weight-to-height ratio; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; 1-u, 1 unit (per cm).

For this column, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

χ2 test.

Multiple regression analysis.

Bivariate logistic regression.

ANOVA.

2-sample t test.

Multinomial logistic regression.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Study characteristics

Among the included studies, 10 articles were of a case-control design (26–28, 30, 31, 34–36, 38, 39), whereas the other 6 did not enroll matched controls (19, 20, 29, 32, 33, 37). Fifteen studies were conducted in economically privileged areas (19, 20, 26–36, 38, 39), whereas one was performed in an indigenous Australian area (37). The lack of evidence from developing countries might lead to bias of the outcomes. Only one paper assessed the status of preschool children (20), 6 articles reported data of adolescents aged >12 (28, 33, 35, 37–39), and the other 9 articles studied children with mixed dentition or with a wide age range (19, 26, 27, 29, 32, 34, 36).

Most of the papers employed BMI (adjusted for age and sex), which made compiling evidence much easier (26, 29–31, 33–35, 39). However, markers of periodontal status varied considerably. Both clinical and laboratory indicators were used in the included papers, e.g., VPI, BOP, PD, LOA, calculus, plaque index, gingival index (GI), Community Periodontal Index, flow rate of salivary secretion, cytokines, and bacteria. To provide a comprehensive review of evidence, data were summarized qualitatively with a descriptive summary and quantitatively through meta-analyses. According to the result of the STROBE checklist, the scores of the included papers ranged from 17.0 to 25.0, with a mean score of 20.3 ± 2.70. Inter-reviewer agreement was 0.79 ± 0.10. Among the 16 included papers, 2 described the relation between preterm delivery and oral health (28, 36) and 2 evaluated the BMI–periodontitis link in children with systemic diseases (19, 32). Because of differences in the hypotheses, data from these 4 studies (19, 28, 32, 36) were not pooled with the other 12 included studies. Seven meta-analyses were conducted in this systematic review based on different variables; only 2 or 3 papers were included in each forest plot because of heterogeneity of variables. Funnel plots presented symmetric inverted shapes, which indicated that the eligible studies were free from substantial bias or systematic heterogeneity (Supplemental Figures 1–6). It is noteworthy that the participants in 3 articles (26, 30, 31) were recruited from the same institute (Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Dental Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden). Those 3 articles were treated as 3 separate studies for analysis because of the differences in sample size and the participants’ ages.

Clinical markers of periodontal diseases

VPI.

Seven of 9 papers employed VPI as an exposure for their studies (20, 26, 27, 29–31, 35). However, because of the various methods employed in VPI data processing and statistical analysis, meta-analysis was conducted in only 3 articles (26, 30, 31) that showed high homogeneity (q = 0.20, df = 2, P = 0.906, I2 = 0.0%). Obese children were 4.75 times as likely (95% CI: 2.42, 9.34) to have >25% of teeth sites with visible plaque compared with normal-weight children (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Scorzetti et al. (27) reported similar results when they employed “presence of visible plaque in 6–12 teeth” as “moderate plaque accumulation.” However, Nascimento et al. (29) argued that prevalence of gingivitis was not associated with BMI. Peng et al. (20) also reported that the weight-to-height, BMI, WC, WHR, and TRSKF z scores were not associated with VPI in 5-y-old children. Moreover, no significant difference in plaque-harboring sites was found between the obesity group and control group (35). Overall, 4 articles (26, 27, 30, 31) demonstrated a positive connection, whereas 3 papers (20, 29, 35) found no relation between VPI and anthropometric measurements.

BOP.

The BOP was accepted as another important indicator of periodontal diseases, and it was measured in 7 included papers (26, 27, 29–31, 35, 39). Because the BOP was analyzed differently in these studies, a meta-analysis was only conducted in 3 articles (26, 30, 31). The pooled estimate of the forest plot has shown that children and adolescents who were obese had a higher chance of having >25% of bleeding tooth sites (OR: 5.41; 95% CI: 2.75, 10.63) than did the normal-weight group (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). Our results compare favorably with the studies from Scorzetti et al. (27) and Fadel et al. (38), in which obesity was found to be associated with marginal bleeding. However, Nascimento et al. (29) and Petti et al. (39) claimed that gingivitis occurrence was not associated with BMI. Overall, most of papers (26, 27, 30, 31, 35) concluded that the BOP was associated with overweight/obesity in children and adolescents.

Calculus, PD, and LOA.

Both Modéer et al. (31) and Zeigler et al. (26) evaluated supragingival and subgingival calculus as markers of periodontal diseases. In terms of subgingival calculus, our meta-analysis revealed that obese children might be at an increased risk of subgingival calculus (OR: 3.07; 95% CI: 1.10, 8.62) (Figure 4). However, diverse outcomes were found with respect to the association between supragingival calculus and obesity (OR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.60, 1.94) (Figure 5).

Probe depth was assumed to be a key sign of periodontitis, and 4 of 10 papers employed PD as a predictor in their research (27, 31, 35, 38). Similar to the BOP, a strong positive association between PD (>4 mm) and obesity was observed in our meta-analysis of 2 articles (OR: 14.15; 95% CI: 5.10, 39.25) (27, 31) (Figure 6). However, some authors argued that there was no difference in PD between the obesity group and the control group (35).

Few studies have investigated variable LOA; Modéer et al. (31) and Scorzetti et al. (27) both reported no association between BMI and LOA. Reeves et al. (38) agreed that young adults were more likely to have periodontitis with increased weight (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.09) and waist circumference (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.08), whereas adolescents were not at increased risk of periodontitis with overweight or central adiposity. However, after adjusting for confounders, Jamieson et al. (37) found that young indigenous Australians with shorter stature were more likely to suffer from periodontal diseases.

Flow rate of salivary secretion.

A meta-analysis was conducted in 3 articles (26, 30, 35) that evaluated the correlation between stimulated flow rate of salivary secretion and obesity in children and adolescents. Tests for heterogeneity demonstrated nonsignificant but substantial heterogeneity among studies (q = 4.90, df = 2, P = 0.086, I2 = 59.1%). The pooled estimates showed that obese participants had a significant reduction in salivary secretion of 0.89 mL/min (95% CI: −1.18, −0.61) compared with nonoverweight participants (P < 0.001) (Figure 7).

Inflammatory markers and microorganisms in periodontal diseases

Obese participants had higher concentrations of IL-1β, IL-8 (31), and secretory IgA (35) than did the control group in 2 studies. This result may be extended to microorganism composition, e.g., Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteroides, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and sum of bacterial cells (26). However, Zeigler et al. (26) found that Spirochetes in gingival cervical fluid (GCF), the serum transudate found in the gingival sulcus, was not associated with adiposity.

Birth weight and periodontal diseases

Two studies (28, 36) reported a possible association between preterm delivery and periodontal health. It was evident that low-birth-weight children had more plaque (36), a higher prevalence of BOP (28), and lower salivary secretion (28) than did controls. In contrast, no significant difference in the number of children with periodontal pockets was found between extremely preterm children and controls (28).

Obese children with systemic diseases and periodontal diseases

Evidence suggested a positive association between the obesity component in metabolic syndrome and periodontal status in children with a family history of obesity (19). For every 1 unit (per cm) increase in waist circumference (peripheral obesity), mean GCF TNF-α increased by 0.6% in boys; an inconsistent result was found in girls. It is also important to note that abdominal obesity was not associated with extent of gingival bleeding in girls or boys. Lalla et al. (32) found that BMI was not associated with gingivitis (at least 2 teeth with bleeding) in 6–18-y-old children with diabetes, whereas BMI might be associated with periodontitis (at least 2 teeth with attachment loss) for those children.

Nutrient/calorie intake and periodontal diseases

There was considerable variability in the assessment of calorie and nutrient intake in the included studies. Petti et al. (39) found that riboflavin, calcium, and frequency of fiber intake were negatively correlated with gingivitis. Boys with low HDL cholesterol or high TGs had higher mean GCF TNF-α than did those without this condition, whereas there was no association between the extent of gingival bleeding and HDL cholesterol or TGs in boys or girls (19). Other authors tried to adjust frequency of fiber, micronutrient (39), vitamin, calcium (38), or sugar (37) consumption; dietary assessment score (35); dietary habit (36); or the BMI-for-age–based nutritional status indicator (32) to examine the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal diseases.

Discussion

The results of this systematic review showed a negative association between BMI and salivary secretion and positive associations between BMI and gingival bleeding, subgingival calculus, increased cell hormones, and bacteria in GCF, which was consistent with previous reviews of studies in adults (15, 16). However, there was no single consensus on the relation between anthropometric measurements and VPI, supragingival calculus, PD, or LOA. We found that obesity might be related to some signs of periodontal diseases in children and adolescents, according to the meta-analyses, particularly with respect to gingival inflammation.

Several hypotheses might help to explain the conclusions. Early theories of the mode of linkage between obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections were raised by Genco et al. (40), who concluded that adiposity in adults was a significant indicator of periodontal disease and that insulin resistance might mediate this association. Other biological pathways also have been suggested by some scholars; fat tissue dysfunction has been believed to produce a vast amount of adipose-tissue–derived hormones and adipokines/adipocytokines, which are the markers of proinflammatory tissues (41). Goodson et al. (42) proposed that the change in salivary microbiological composition in the overweight population indicated that specific bacteria species were risk factors for excessive weight gain. Apart from the mechanism mentioned above, another possible explanation of the findings was variation in included participants. A lack of variables that have been agreed upon may have triggered these contradictory results. For example, to evaluate the plaque accumulation of participants, VPI was believed to be one of the most popular indices. Modéer et al. (30, 31) and Zeigler et al. (26) used “>25% sites of all teeth with visible plaque” as an indicator of gingival inflammation, whereas Scorzetti et al. (27) employed “presence of visible plaque in 6–12 teeth” as the variable in their paper. Not many articles studied PD or LOA, because the most prevalent periodontal diseases (e.g., chronic periodontitis) shared long-lasting latent periods and would not initiate bone loss in an early stage. Moreover, children and adolescents were experiencing tooth eruption, which made the assessment of infrabony defects difficult. Therefore, it is reasonable that inconclusive associations were found between PD and LOA and obesity.

Several studies included in this review mentioned the active role of micronutrients and macronutrients (37–39). Included studies revealed that nutritional deficiencies (e.g., riboflavin, calcium, and frequency of fiber intake) increased the prevalence of gingivitis in adolescents (39). This association was supported by animal (43) and human studies (44) in earlier work. It was also reported that a reduced intake of 25-hydroxyvitamin D increased the risk of gingival inflammation (45). In terms of overnutrition, an effective study demonstrated that high TGs were related to periodontal diseases in children with metabolic syndrome (19). This correlation is well explained by the animal study by Tomofuji et al. (46), which showed that bone resorption was initiated and accelerated in a high-cholesterol rat model because of the proliferation of junctional epithelium. According to these findings, excessive intake of foods rich in cholesterol and TGs may lead to both obesity and periodontal diseases in children and adolescents, whereas foods rich in riboflavin, fiber, calcium, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D help lower the risk of gingivitis (39). Marginal micronutrient deficiencies and overnutrition frequently coexist in overweight or obese individuals as a consequence of unhealthy dietary habits in developed countries (39). Consuming a high-quality diet and maintaining normal weight help to lower prevalence of periodontal diseases (47).

Several limitations should be noted in the present review. It is reasonable to consider that a lack of articles in other languages may introduce bias. Moreover, only 2 or 3 papers were enrolled in each meta-analysis and the results of the meta-analyses may also be limited by the publication bias of statistically positive outcome.

Interesting as these studies may be, it must be realized that most of them only provide cross-sectional information and that there was a lack of evidence on the causal association. There is a strong need for conducting a more careful longitudinal study, because research evidence is lacking to clarify issues. In order to minimize the bias of oral health knowledge and awareness, education programs before oral examination are recommended; in addition, related potential confounders need to be adjusted (40). Moreover, it is recognized that BMI is a key indicator of adiposity, but little is known about other adiposity proxies. Continuing assessment of central adiposity (WC and WHR) and peripheral adiposity (TRSKF) is recommended to widen the evidence base for the association (12).

This systematic review has described and summarized the evidence regarding the association between anthropometric measurements and periodontal health status in children and adolescents. However, the causal relation between anthropometric measurements and periodontal diseases in children and adolescents remains unknown and has become an emerging public concern. In light of current research evidence, it is of significant importance to further investigate the common pathogenesis of anthropometry and periodontal diseases. It is encouraging to find emerging evidence that is shedding light on the association between anthropometry, nutrition intake, dietary habits, and periodontitis, but little convincing research-based data were shown to explain the potential mechanism of macronutrients and micronutrients on this relation (as an independent mechanism or a secondary consideration). Given the dearth of evidence on this key health issue, we recommend future studies with a comprehensive prospective cohort design and with more potential variables, including anthropometric measurements, nutrient/calorie intake indexes, and dietary habits.

Acknowledgments

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: BOP, bleeding on probing index; GCF, gingival cervical fluid; GI, gingival index; LOA, loss of attachment; PD, probing depth; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; STROBE, STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology; TRSKF, triceps skinfold thickness; VPI, visible plaque index; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

References

- 1.World Health Organization [Internet]. Oral Health Fact sheets. 2012. [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en/.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Periodontal Disease. [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/periodontal_disease/index.htm.

- 3.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century—The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31 Suppl. 1:3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Lalla E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40:S113–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambrone L, Guglielmetti MR, Pannuti CM, Chambrone LA. Evidence grade associating periodontitis to preterm birth and/or low birth weight: I. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J Clin Periodontol 2011;38:795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003;95:559–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Andrade FB, de Franca Caldas A Jr, Kitoko PM. Relationship between oral health, nutrient intake and nutritional status in a sample of Brazilian elderly people. Gerodontology 2009;26:40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, Lowe C, Finch S, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Walls AW. The relationship among dental status, nutrient intake, and nutritional status in older people. J Dent Res 2001;80:408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tôrres LH, da Silva DD, Neri AL, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, Sousa ML. Association between underweight and overweight/obesity with oral health among independently living Brazilian elderly. Nutrition 2013;29:152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida N, Tanaka M, Hayashi N, Nagata H, Takeshita T, Nakayama K, Morimoto K, Shizukuishi S. Determination of smoking and obesity as periodontitis risks using the classification and regression tree method. J Periodontol 2005;76:923–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meisel P, Wilke P, Biffar R, Holtfreter B, Wallaschofski H, Kocher T. Total Tooth Loss and Systemic Correlates of Inflammation: Role of Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:644–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jagannathachary S, Kamaraj D. Obesity and periodontal disease. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2010;14:96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden G, Patterson C, Evans A, Kee F. Obesity and periodontitis in 60–70-year-old men. J Clin Periodontol 2007;34:461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suvan JE, Petrie A, Nibali L, Darbar U, Rakmanee T, Donos N, D'Aiuto F. Association between overweight/obesity and increased risk of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2015;42:733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaffee BW, Weston SJ. Association between chronic periodontal disease and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2010;81:1708–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suvan J, D'Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults. A systematic review. Obes Rev 2011;12(5):e381–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization [Internet]. Oral health surveys: basic methods—5th edition. [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/oral_health/publications/9789241548649/en/.

- 18.Katz J, Bimstein E. Pediatric obesity and periodontal disease: a systematic review of the literature. Quintessence Int 2011;42(7):595–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kâ K, Rousseau MC, Lambert M, Tremblay A, Tran SD, Henderson M, Nicolau B. Metabolic syndrome and gingival inflammation in Caucasian children with a family history of obesity. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40:986–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng SM, McGrath C, Wong HM, King NM. The relationship between oral hygiene status and obesity among preschool children in Hong Kong. Int J Dent Hyg 2014;12:62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Biotechnology Information [Internet]. MeSH: Child [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=Child.

- 22.National Center for Biotechnology Information [Internet]. MeSH: Preschool Child [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=Preschool Child.

- 23.National Center for Biotechnology Information [Internet]. MeSH: Adolecent [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=Adolescent.

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med 2009;3:e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.University of Bern [Internet]. STROBE Statement. [cited 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_combined.pdf.

- 26.Zeigler CC, Persson GR, Wondimu B, Marcus C, Sobko T, Modeer T. Microbiota in the Oral Subgingival Biofilm Is Associated With Obesity in Adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scorzetti L, Marcattili D, Pasini M, Mattei A, Marchetti E, Marzo G. Association between obesity and periodontal disease in children. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2013;14(3):181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rythén M, Niklasson A, Hellstrom A, Hakeberg M, Robertson A. Risk indicators for poor oral health in adolescents born extremely preterm. Swed Dent J 2012;36:115–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nascimento GG, Seerig LM, Vargas-Ferreira F, Correa FO, Leite FR, Demarco FF. Are obesity and overweight associated with gingivitis occurrence in Brazilian schoolchildren? J Clin Periodontol 2013;40:1072–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modéer T, Blomberg CC, Wondimu B, Julihn A, Marcus C. Association between obesity, flow rate of whole saliva, and dental caries in adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:2367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modéer T, Blomberg C, Wondimu B, Lindberg TY, Marcus C. Association between obesity and periodontal risk indicators in adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6(2–2):e264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, Kaplan S, Softness B, Greenberg E, Goland RS, Lamster IB. Diabetes-related parameters and periodontal conditions in children. J Periodontal Res 2007;42:345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Sanchez-Perez L, Molina-Frechero N, Velazquez-Alva C, Zepeda-Zepeda M, Borges-Yanez A. The relationship between body mass index and body fat percentage and periodontal status in Mexican adolescents. Acta Odontol Scand 2014;72:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franchini R, Petri A, Migliario M, Rimondini L. Poor oral hygiene and gingivitis are associated with obesity and overweight status in paediatric subjects. J Clin Periodontol 2011;38:1021–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fadel HT, Pliaki A, Gronowitz E, Mårild S, Ramberg P, Dahlèn G, Yucel-Lindberg T, Heijl L, Birkhed D. Clinical and biological indicators of dental caries and periodontal disease in adolescents with or without obesity. Clin Oral Investig 2014;18:359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brogårdh-Roth S, Matsson L, Klingberg G. Molar-incisor hypomineralization and oral hygiene in 10- to-12-yr-old Swedish children born preterm. Eur J Oral Sci 2011;119:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamieson LM, Sayers SM, Roberts-Thomson KF. Associations between oral health and height in an indigenous Australian birth cohort. Community Dent Health 2013;30:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeves AF, Rees JM, Schiff M, Hujoel P. Total body weight and waist circumference associated with chronic periodontitis among adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:894–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petti S, Cairella G, Tarsitani G. Nutritional variables related to gingival health in adolescent girls. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000;28:407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodont 2005;76(11):2075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bluher M. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes: official journal, German Society of Endocrinology and German Diabetes Association 2009;117(6):241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodson JM, Groppo D, Halem S, Carpino E. Is obesity an oral bacterial disease? Journal of Dental Research 2009;88(6):519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliver WM. The effect of deficiencies of calcium, vitamin D or calcium and vitamin D and of variations in the source of dietary protein on the supporting tissues of the rat molar. J Periodontal Res 1969;4:56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freeland JH, Cousins RJ, Schwartz R. Relationship of mineral status and intake to periodontal disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1976;29:745–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietrich T, Nunn M, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and gingival inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomofuji T, Kusano H, Azuma T, Ekuni D, Yamamoto T, Watanabe T. Effects of a high-cholesterol diet on cell behavior in rat periodontitis. J Dent Res 2005;84:752–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Zahrani MS, Borawski EA, Bissada NF. Periodontitis and three health-enhancing behaviors: maintaining normal weight, engaging in recommended level of exercise, and consuming a high-quality diet. J Periodontol 2005;76:1362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]