Abstract

Amoebae play an important ecological role as predators in microbial communities. They also serve as niche for bacterial replication, harbor endosymbiotic bacteria and have contributed to the evolution of major human pathogens. Despite their high diversity, marine amoebae and their association with bacteria are poorly understood. Here we describe the isolation and characterization of two novel marine amoebae together with their bacterial endosymbionts, tentatively named ‘Candidatus Occultobacter vannellae’ and ‘Candidatus Nucleophilum amoebae’. While one amoeba strain is related to Vannella, a genus common in marine habitats, the other represents a novel lineage in the Amoebozoa. The endosymbionts showed only low similarity to known bacteria (85–88% 16S rRNA sequence similarity) but together with other uncultured marine bacteria form a sister clade to the Coxiellaceae. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization and transmission electron microscopy, identity and intracellular location of both symbionts were confirmed; one was replicating in host-derived vacuoles, whereas the other was located in the perinuclear space of its amoeba host. This study sheds for the first time light on a so far neglected group of protists and their bacterial symbionts. The newly isolated strains represent easily maintainable model systems and pave the way for further studies on marine associations between amoebae and bacterial symbionts.

Unicellular eukaryotes, in particular free-living amoebae, are major players in the environment. Free-living amoebae are ubiquitous in soil, fresh- and seawater, but can also be found in anthropogenic environments, such as cooling towers, water pipes and waste-water treatment plants1,2. Taxonomically, free-living amoebae are scattered across the eukaryotic tree of life, with the supergroup Amoebozoa containing a substantial part of known free-living amoebae, such as naked lobose amoebae (gymnamoebae)3,4. In total, there are more than 200 described species of gymnamoebae classified into over 50 genera5. A substantial proportion of this diversity is found in marine environments, and some genera represent exclusively marine lineages. Yet our current knowledge of marine amoebae is still scarce.

Free-living amoebae shape microbial communities; they control environmental food webs by preying on bacteria, algae, fungi and other protists and contribute to elemental cycles in diverse ecosystems1. Free-living amoebae typically take up their food by phagocytosis. However, some bacteria have developed strategies to survive digestive processes and eventually use amoebae as niche for intracellular replication6,7,8,9. Free-living amoebae are thus considered to have served as evolutionary training ground for intracellular microbes. Bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila, Francisella tularensis, or Mycobacterium species transiently exploit these protists as a vehicle to reach out for higher eukaryotic hosts. Others engage in long-term, stable associations with free-living amoebae7,8, which can be beneficial, neutral or parasitic for their hosts. These obligate intracellular symbionts include a diverse assemblage of phylogenetically different bacterial groups10,11,12 and their analysis has provided unique insights into the evolution of the intracellular life style13,14. However, virtually nothing is known about bacterial symbionts in marine amoebae.

Here we report on the isolation and characterization of two novel marine amoeba strains harboring obligate intracellular bacterial symbionts. Both bacteria represent deeply branching novel lineages in the Gammaproteobacteria affiliated with the Coxiellaceae. While one of the symbionts replicates in the amoeba cytoplasm, the other exploits a highly unusual intracellular niche, its host’s perinuclear space.

Methods

Amoeba isolation and cultivation

Lago di Paola is a meso-eutrophic lake located on the Tyrrhenian coast of Central Italy (Latium). Two narrow artificial channels at the northwestern and southeastern ends of the lake allow for a limited water exchange with the sea, sustaining a high degree of salinity throughout the year (33.7 during sampling). A surface water sample was collected on October 1, 2013, from station SAB215. The number of protist-sized particles per milliliter lake water was determined with a Neubauer counting chamber. Between one and ten protist-sized particles were placed in wells on a 96-well plate (Corning Costar, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) containing 200 μl artificial seawater (ASW, DSMZ 607) and E. coli tolC- as well as ampicillin (200 ng/ml)11. The amoeba strain A1, which was propagating on these plates was screened for the presence of bacterial endosymbionts with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and maintained in cell culture flasks (Nunclon delta-surface, Thermo Scientifc, Germany) containing ASW and E. coli tolC- as well as ampicillin (200 ng/ml).

Grains of wet sand collected on a sea shore (Montego Bay, Jamaica) were placed onto a MY75S agar plate and moistened daily with ASW (75%) as described previously16. Two weeks later, a morphologically uniform group of cells was transferred onto a new MY75S plate, and the newly established amoeba strain JAMX8 was sub-cultured either on plates or in liquid medium containing ASW and E. coli tolC- as well as ampicillin (200 ng/ml).

Trophozoites of both strains were observed in hanging drop preparations and documented using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) and an Olympus DP70 camera (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Japan). Trophozoites and cellular structures were analyzed using ImageJ software17.

Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), ASW in culture flasks containing strain A1 was replaced with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer. Trophozoites of strain JAMX8 were fixed in situ on MY75S plates with the same fixative. Pelleted trophozoites were rinsed in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded acetone series, and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol and Reynold’s lead citrate and examined using a JEOL JEM 1010 electron microscope (Jeol Ltd, Japan) operating at 80 kV.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Amoeba cells were harvested by centrifugation (3000 × g, 8 min), washed with ASW and left to adhere on slides for 30 min prior to fixation with 4% formaldehyde (15 min at room temperature). The samples were hybridized for two hours at 46 °C at a formamide concentration of 25% using standard hybridization and washing buffers18 and a combination of the following probes: symbiont specific probes JAMX8_197 (5′-GAAAGGCCAAAACCCCCC-3′) or A1_1033 (5′-GCACCTGTCTCTGCATGT-3′), together with EUK-516 (5′-ACCAGACTTGCCCTCC-3′19) targeting most eukaryotes and the EUB338 I-III probe mix (5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′, 5′-GCAGCCACCCGTAGGTGT-3′, 5′-GCTGCCACCCGTAGGTGT-3′ 20) targeting most bacteria. FISH probes were designed based on a multiple 16S rRNA sequence alignment in the software ARB21 using the integrated probe-design tool. Furthermore, thermodynamic parameters and binding specificity were evaluated with the web-based tools mathFISH and probeCheck22,23. All probes were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Germany). Cells were subsequently stained with DAPI (0.5 μg/ml in double distilled water, 3 min), washed once and embedded in Citifluor (Agar-Scientific, UK). Slides were examined using a confocal laser scanning microscope (SP8, Leica, Germany).

DNA extraction, PCR, cloning and sequencing

DNA was extracted from infected amoeba cultures using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Austria). Amoebal 18S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR using primers 18e (5′-CTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT-3′) and RibB (5′-TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTA-3′) at an annealing temperature of 52 °C24,25. Bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified using primers 616 V (5′-AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) at an annealing temperature of 52 °C26,27. PCR reactions typically contained 100 ng template DNA, 50 pmol of each primer, 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (TopBio, Czech Republic for 18S rDNA; Fermentas, Germany for 16S rDNA), 10x Taq buffer with KCl and 2 μM MgCl2 and 0.2 μM of each deoxynucleotide in a total volume of 50 μl. PCR products were purified using the PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany) and cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleotide sequences were determined at Microsynth (Vienna, Austria) and Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Newly obtained rRNA gene sequences were deposited at Genbank/EMBL/DDBJ (accession numbers LC025958, LC025959, LC025974, LC025975).

Phylogenetic analysis

To infer the phylogenetic position of the isolated amoeba strains in the Amoebozoa a representative dataset of 18S rRNA sequences from a total of 57 taxa was compiled. The length of the final trimmed alignment was 1226 nt; alternative alignments obtained by altering taxon sampling and/or trimming stringency were also analyzed to check the stability of deeper nodes. A more detailed analysis of the position of strain A1 in the Vannellidae was performed, comprising in total 19 taxa, both nominal species and unnamed sequences assigned to morphologically characterized strains. The alignment was processed as described above and trimmed to a final length of 1440 nt. Both datasets were analyzed using with RAxML 8.0.2028, with the GTR gamma model of evolution and rapid bootstrapping (1000 replicates). Bayesian interference analysis was computed for both datasets in MrBayes 3.1.229 with default options, GTR gamma model and 106 generations; burnin 25%.

For phylogenetic analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA sequences the sequence editor integrated in the software ARB was used to build alignments based on the current Silva ARB 16S rRNA database21,30, which was updated with sequences from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ obtained by sequence homology searches using BLASTn available at the NCBI web site (National Centre for Biotechnology Information31,32). The alignment was trimmed to the length of the shortest sequence, manually curated and exported from ARB using a 50% conservation filter. The resulting alignment comprised 61 sequences and 1417 positions. For Bayesian analysis, PhyloBayes33 was used with two independent chains under GTR and the CAT + GTR model. Both analyses ran until convergence was reached (maxdiff < 0.1) and as burnin 25% of the sampled trees were removed. Posterior predictive tests were performed in PhyloBayes with the ppred program (sampling size 1000 trees).

Results

Two novel stenohaline amoebae containing bacterial symbionts

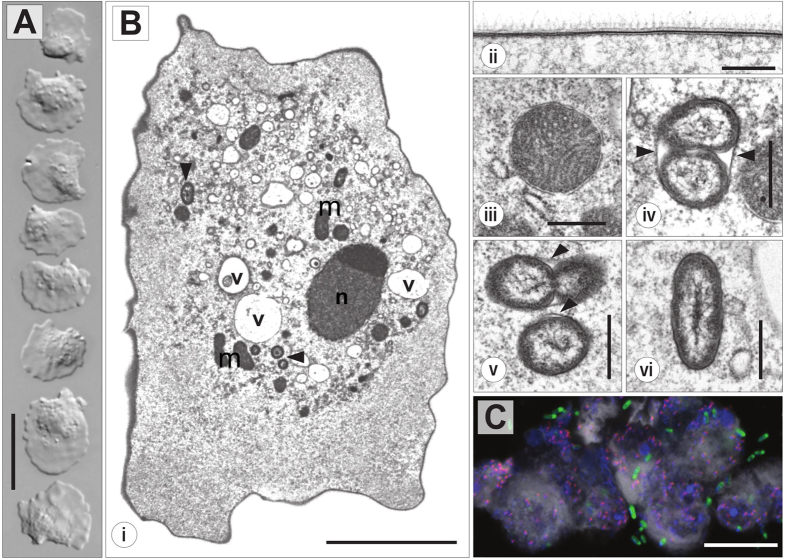

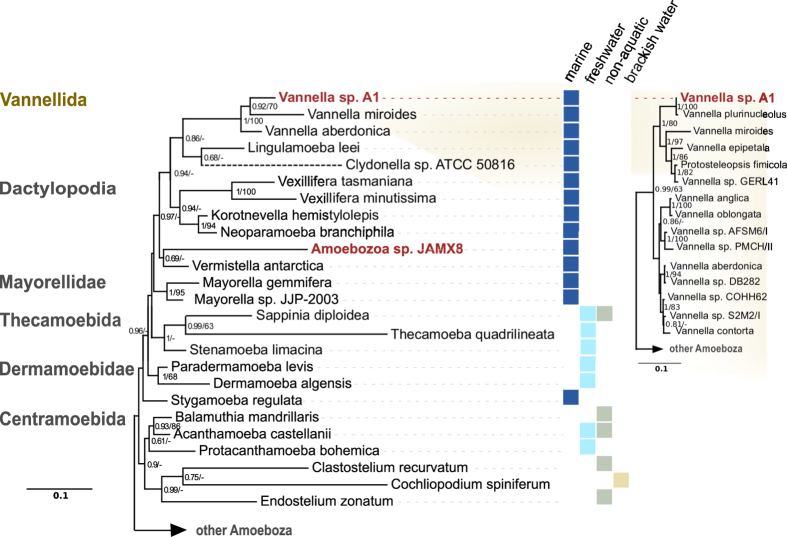

Two novel strains of marine amoebae, initially referred to as A1 and JAMX8, were isolated from samples taken from a coastal lake in Italy and a sea shore in Jamaica, respectively. Both amoeba strains were successfully cultivated only in artificial seawater. They were truly stenohaline, shown by their incapability to grow under varying salt concentrations. In hanging drop preparations, strain A1 exhibited a flattened, oval to fan-shaped locomotive form (Fig. 1A) with an average length of 17.5 μm (S.D. 2.5, n = 50), width of 15.7 μm (S.D. 2.4, n = 50) and a length/width ratio of 0.8–1.6 (in average 1.1). The anterior hyaloplasm typically occupied about half the cell length. At the ultrastructure level, the cytoplasm contained a nucleus with a peripheral nucleolus or nucleoli, oval mitochondria and food vacuoles (Fig. 1Bi). The cell surface was covered with fine, hair-like filamented glycostyles (length of 71 ± 9 nm) (Fig. 1Bii). The mitochondria possessed branching tubular cristae (Fig. 1Biii). The partial 18S rRNA gene sequence (1889 nt) of strain A1 was most similar to Vannella plurinucleolus and other Vannella species (98% sequence similarity). In our phylogenetic analyses the placement of strain A1 in the family Vannellidae was highly supported (Figs 2 and S1) and further confirmed by a more detailed analysis focusing on the Vannellidae only, in which V. plurinucleus appeared as closest relative (Fig. 2 inset, S1).

Figure 1. Vannella sp. A1 and its bacterial endosymbiont ‘Candidatus Occultobacter vannellae’.

(A) Trophozoites as seen in hanging drop preparations (scale bar = 20 μm). (B) Fine structure of Vannella sp. A1 and its bacterial symbiont. (i) Section of an amoeba trophozoite: cell organelles located within granuloplasm; nucleus (n) with laterally located nucleolus, mitochondria (m), vacuoles (v), bacterial endosymbionts (arrowheads) (scale bar = 5 μm). (ii) Cell surface of trophozoite with amorphous glycocalyx (scale bar = 200 nm). (iii) Mitochondria with tubular cristae (scale bar = 500 nm). (iv–vi) Bacterial endosymbionts in detail: (iv, v) host-derived vacuolar membranes (arrowheads) enclosing endosymbionts undergoing cell division, (vi) longitudinal section through an endosymbiont (scale bar = 500 nm). (C) Fluorescence in situ hybridization image showing the intracytoplasmic location of ‘Candidatus Occultobacter vannellae’ (Occultobacter-specific probe A1_1033, pink) in its Vannella sp. A1 host (probe EUK516, grey) with DAPI stained nuclei (blue) and food bacteria (general bacterial probe EUB338-mix, green); scale bar indicates 10 μm.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships of Vannella sp. A1 and amoeba isolate JAMX8 within the Amoebozoa.

Phylogenetic 18S rRNA-based trees of the Amoebozoa (left panel) and Vannellidae (right panel) constructed using the Bayesian inference method. Bayesian posterior probabilities (>0.6) and RaxML bootstrap support values (>60%) are indicated at the nodes; the dashed line indicates a branch shortened by 50% to enhance clarity. Colored squares indicate the typical habitat of the respective amoeba species (left panel). A detailed version of the trees including accession numbers is available as supplementary Figure S1.

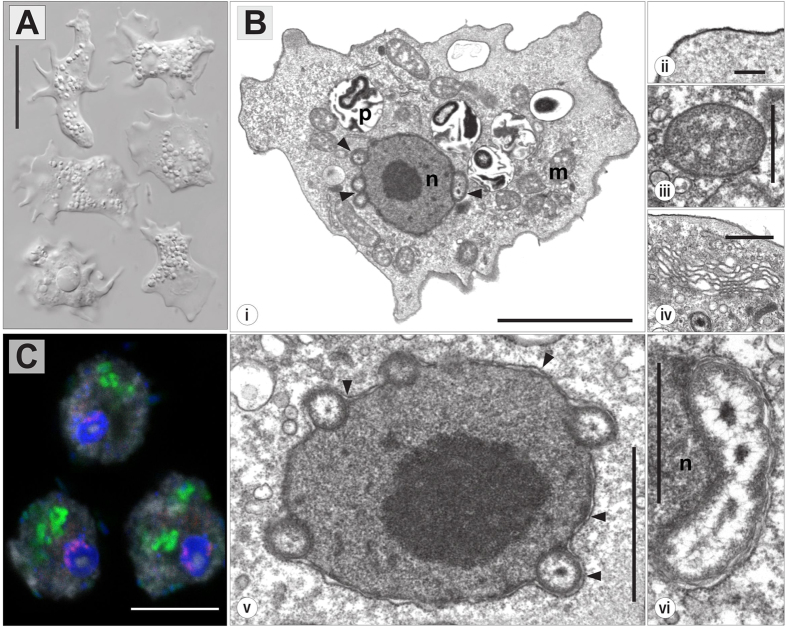

The second isolate, strain JAMX8, showed flattened trophozoites with variable shape with an average length of 19.9 μm (S.D. 3.9, n = 26), width of 16.3 μm (S.D. 3.5, n = 26) and length/width ratio 0.88–1.84 (in average 1.25) (Fig. 3A). A frontal irregular hyaline zone occupied about one third of the cell length and was clearly separated from the granuloplasm containing a large quantity of spherical granules. The hyaloplasm possessed typically one to three longitudinal ridges. The locomotive cells often produced short dactylopodia (usually not more than 5 μm in length) that could freely move horizontally or vertically. No cysts were observed during subculturing. Floating forms consisted of a spherical central body with an average size of 4.8 μm in diameter (S.D. 0.7, n = 20) and thin radiating pseudopodia not longer than 10 μm (6.3 μm in average). A single, vesicular nucleus was located near the border of the granuloplasm (Fig. 3A,Bi,v). The cell surface was covered with a thin and amorphous cell coating (Fig. 3Bii). The cytoplasm contained numerous phagosomes (Fig. 3Bi), rounded or ovoid mitochondria (Fig. 3Bi,iii) with tubular cristae (Fig. 3Biii) and a Golgi complex organized as dictyosome (Fig. 3Biv). Comparison of the partial 18S rRNA sequence (2081 nt) of strain JAMX8 with known sequences revealed the absence of highly similar sequences in the NCBI nr/nt database. Taxa with moderate sequence similarity (<88%) were scattered among various amoebozoan lineages. In our phylogenetic analyses the JAMX8 strain represented a deeply branching novel lineage in the Amoebozoa with no clear affiliation to described taxa (Figs 2, S1).

Figure 3. Amoeba isolate JAMX8 and its bacterial endosymbiont ‘Candidatus Nucleophilum amoebae’.

(A) Trophozoites as seen in hanging drop preparations (scale bar = 20 μm). (B) Fine structure of JAMX8 and its bacterial endosymbiont inhabiting the perinuclear space. (i) Section of an amoeba trophozoite: vesicular nucleus (n), phagosomes (p), mitochondria (m), bacterial endosymbionts associated with the nuclear envelope (arrowheads) (scale bar = 5 μm). (ii) Amorphous and tenuous cell coat (scale bar = 200 nm). (iii) Mitochondria with tubular cristae (scale bar = 1 μm). (iv) The Golgi complex organized as dictyosome (scale bar = 1 μm). (v,vi) Bacterial endosymbionts located within the perinuclear space, between inner and outer nuclear membrane. (v) Nucleus in detail with numerous endosymbiotic bacteria in transverse section (scale bar = 2 μm). Arrowheads indicate outer nuclear membrane. (vi) Longitudinal section through a rod-shaped bacterial endosymbiont, nucleus (n) (scale bar = 1 μm). (C) Fluorescence in situ hybridization image showing the co-localization of ‘Candidatus Nucleophilum amoebae’ (Nucleophilum-specific probe JAMX8_197, pink) with its host nucleus (DAPI, blue); food bacteria (general bacterial probe EUB338-mix, green) enclosed in the amoeba cytoplasm (probe EUK516, grey); scale bar indicates 10 μm.

Electron microscopy and staining with the DNA dye DAPI readily revealed the presence of bacterial endosymbionts in both amoeba strains (Figs 1 and 3).

Bacterial endosymbionts in the amoeba cytoplasm and perinuclear space

In addition to ingested bacteria in food vacuoles (Fig. 1Bi), amoeba strain A1 harbored morphologically different rod-shaped bacteria with a diameter of about 0.44 μm and a maximum length of 1.2 μm (Fig. 1Bi,iv–vi). These bacteria were predominantly located enclosed in vacuoles (arrowheads in Fig. 1Biv,v), in which dividing cells were observed (Fig. 1Bv). The bacterial endosymbionts appeared to be few in numbers and scattered throughout the cytoplasm. However, nearly 100% of all amoeba trophozoites were infected.

Ultrastructural analysis of amoeba strain JAMX8 revealed bacterial symbionts at a conspicuous location within the cells (Fig. 3Bi,v,vi); rod-shaped bacteria of about 0.41 μm in diameter and a maximum length of 1.7 μm were found enclosed in the perinuclear space, between the inner and the outer nuclear membrane. Bacteria were never observed within the nucleoplasm. Nearly 100% of amoeba cells were infected. Both amoeba strains showed no apparent signs of symbiont-induced stress or lysis; the symbiotic associations could be stably maintained non-axenically in the lab.

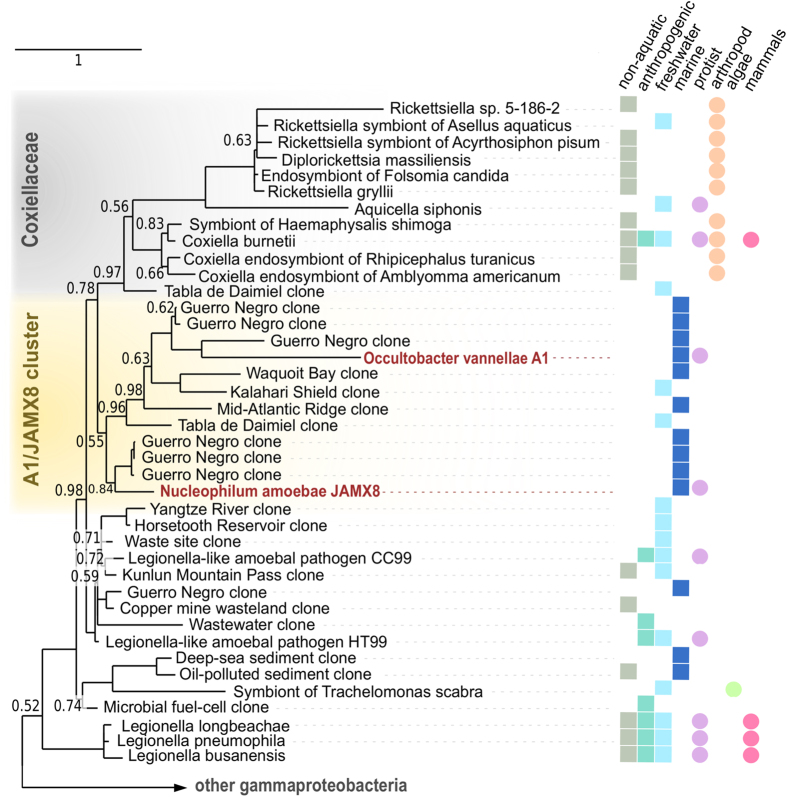

Novel gammaproteobacteria related to the Coxiellaceae

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene revealed that the endosymbiont of amoeba strain A1 showed highest 16S rRNA sequence similarity to Legionella longbeachae (85%) in the NCBI RefSeq database, which contains only sequence information of well described organisms34. The bacterial symbiont was tentatively named “Candidatus Occultobacter vannellae A1” (referring to the hidden location of these bacteria inside their Vannella sp. host and their small cell size; hereafter: Occultobacter). The endosymbiont of amoeba strain JAMX8 was most similar to Coxiella burnettii (88% 16S rRNA sequence similarity), and is provisionally referred to as “Candidatus Nucleophilum amoebae JAMX8” (referring to the association of these bacteria with the amoeba nucleus; hereafter: Nucleophilum). The rRNA sequences of both endosymbionts had a similarity of 85% with each other.

For phylogenetic analysis we first calculated trees with the CAT + GTR and the GTR models in PhyloBayes33. We then used posterior predictive tests to compare the fit of the models to the data (observed diversity: 2.866), indicating that CAT + GTR (posterior predictive diversity: 2.859 +/− 0.027, p-value: 0.57) was superior to the GTR (posterior predictive diversity: 3.138 +/− 0.027, p-value: 0). We therefore used the CAT + GTR model to assess the phylogenetic position of the two endosymbionts, demonstrating that both represent deeply branching lineages in the Gammaproteobacteria (Figs 4, S2). In our analysis they grouped with several marine and freshwater clones, together forming a sister clade to the Coxiellaceae (Bayesian posterior probability = 0.78). Occultobacter and Nucleophilum were also moderately related to a clade comprising the two unclassified amoeba-associated bacteria CC99 and HT99 (Bayesian posterior probability = 0.98)35. We searched published 16S rRNA amplicon and metagenomic sequence datasets using an approach described recently63, but did not find significant numbers of similar sequences to Occultobacter or Nucleophilum at a 97% similarity threshold.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic relationship of ‘Candidatus Occultobacter vannellae’ and ‘Candidatus Nucleophilum amoebae’ with the Gammaproteobacteria.

The phylogenetic tree (PhyloBayes, CAT + GTR) is based on the 16S rRNA sequences, Bayesian posterior probabilities are indicated at the nodes (only values < 0.99 are shown). Colored squares indicate the environmental origin of the respective sequence; colored circles indicate host association. A detailed version of this tree including accession numbers is available as supplementary Figure S2.

In order to demonstrate the intracellular location of the bacterial symbionts FISH experiments were performed by combining symbiont-specific probes with a universal bacterial probe mix20. The positive hybridization reaction with both probes respectively confirmed the location of Occultobacter in the cytoplasm of its Vannella sp. A1 host (Fig. 1C) and the association of Nucleophilum with the nucleus of its JAMX8 amoeba host (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

Here we report on the recovery of two novel stenohaline amoeba from marine samples. Based on light microscopy, amoeba strain A1 was readily identified as a member of the ubiquitous family Vannellidae whose members are also frequently found in marine environments36. Nuclear structure (laterally located nucleolus/nucleoli) and trophozoite size allow an assignment of this strain to Vannella plurinucleolus (Fig. 1). However, the shape of its cell surface is in conflict with the diagnostic features of V. plurinucleolus. Yet, in our phylogenetic analyses strain A1 clustered together with V. plurinucleolus strain 50745 (Fig. 2). As the taxonomy of V. plurinucleolus strain 50745 is under debate37, we decided to leave strain A1 undetermined at the species level. Morphological and molecular characterization of additional Vannella strains will be required to resolve species identification.

By light microscopy, trophozoites of strain JAMX8 showed a combination of morphological features typical of the genera Mayorella and Korotnevella38. However, neither essential diagnostic features, like a surface cuticle or surface microscales, nor any other distinct characteristics were found (Fig. 3). We were thus not able to assign strain JAMX8 to any described gymnamoeba species or genus based on morphological criteria. Furthermore, the placement of JAMX8 within the Amoebozoa could not be unambiguously determined in our phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2). The deeper nodes in our Amoebozoa tree are generally rather unstable, which is consistent with previous studies39,40, and the tree topology was dependent on taxon sampling and alignment trimming stringency. However, strain JAMX8 groups with low statistical support with Vermistella antarctica (Bayesian posterior probability 0.69, maximum likelihood bootstrap value 16%), and this sister taxa relationship was recovered repeatedly in different analyses. Taken together, the exact relationship of strain JAMX8 to known amoebae remains elusive. However, morphological and phylogenetic data suggest that JAMX8 is a representative of a new taxon within the Amoebozoa.

To our knowledge this is the first molecular identification and characterization of bacterial symbionts of marine amoebae. In the last two decades numerous reports described the discovery of obligate intracellular amoeba symbionts8,10. However, these studies were often biased towards the isolation of Acanthamoeba, Naegleria or Vermamoeba (former Hartmannella) strains, usually from anthropogenic or freshwater habitats or clinical samples7,41,42. This is not surprising as these amoebae are in the focus of medical and parasitological research, and standard isolation protocols are available2,16,43,44. Interestingly, bacterial symbionts previously found in these amoebae were frequently very similar to each other; although isolated from geographically distant places, the endosymbionts belonged to symbiont clades either in the Alpha- or Betaproteobacteria, the Bacteroidetes, or the Chlamydiae10,11,45,46,47,48. In addition, Gammaproteobacteria, such as Coxiella, Francisella, Legionella, and Legionella-like amoebal pathogens, may also be associated with amoebae7,48,49,50, but these are mostly facultative associations. These bacteria show a parasitic life style, and many also infect higher eukaryotes7. Our study for the first time reports on Gammaproteobacteria naturally living in a stable association with their amoeba hosts, i.e. host and symbiont can together be maintained in culture over extended periods of time without apparent signs of host cell lysis and 100% of amoebae being infected.

The two gammaproteobacterial symbionts Occultobacter and Nucleophilum represent novel phylogenetically deeply branching lineages, with only low 16S rRNA sequence similarity to known bacteria (85% and 88%, respectively; Fig. 4). In addition, no close relatives (>97% 16S rRNA sequence similarity) could be retrieved in any of the numerous 16S rRNA amplicon studies targeting biodiversity of marine environments, suggesting that both endosymbionts are rather rare and/or their hosts have not been captured during sampling. Our phylogenetic analysis showed that the exact position of the two endosymbionts in the Gammaproteobacteria is difficult to resolve. Occultobacter and Nucleophilum group together in a well-supported monophyletic clade with the Coxiellaceae and a cluster comprising the legionella-like amoebal pathogens HT99 and CC99 (Fig. 4). The topology within this clade is, however, not very robust. This is in agreement with previous observations, highlighting the challenge of resolving the phylogeny of the major Gammaproteobacteria groups51.

The closest relatives of Occultobacter and Nucleophilum are other symbionts and pathogens of eukaryotes. The Coxiellaceae mainly include bacteria infecting arthropods, which occasionally also invade mammalian or protozoan hosts49,52,53. The bacteria referred to as HT99 and CC99 were associated with amoebae found in a hot tub and a cooling tower, respectively35. Worth noting, while the Coxiellaceae, CC99, HT99 and related taxa mainly originate from freshwater, anthropogenic and non-marine habitats, many of the closest relatives of Occultobacter and Nucleophilum were detected in marine environments (Fig. 4).

The two symbionts described here colonize fundamentally different intracellular niches. Whereas, similar to many known intracellular bacteria, Occultobacter establishes replication inside host-derived vacuoles and is also occasionally found as single cell inside the cytoplasm, Nucleophilum is associated with its host cell’s nucleus (Figs 1 and 3). The latter is a very unusual life style54,55, but there are few reports on bacteria located in the nuclear compartment of other amoebae, namely the chlamydial symbiont of Naegleria ‘Pn’56,57, the two gammaproteobacteria HT99 and CC9935, and the alphaproteobacterium Nucleicultrix amoebiphila58. Bacteria capable to invade the nucleus possibly benefit from a nutrient-rich environment, protection from cytoplasmic defense mechanisms and a direct path to vertical transmission during host cell replication55. However, the pattern of how bacteria settle in this compartment shows striking differences; while Nucleicultrix is spread out in the nucleoplasm, Pn is associated with the nucleolus, and Nucleophilum is located in the perinuclear space56,57,58. Embedded in between the inner and outer nuclear membrane, the bacteria thus do not have direct access to the nucleoplasm. The perinuclear space, which is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum, serves as a calcium storage59 and has regulatory impact on processes in the nucleus, such as gene expression60. The exact physicochemical conditions of this compartment remains currently unknown59, however, in contrast to the nucleoplasm or the cytoplasm it likely contains less substrates to support bacterial growth. We therefore expect Nucleophilum to have evolved unconventional strategies to target its peculiar perinuclear niche and to satisfy its nutritional requirements. Previously, it has been shown and hypothesized that some intranuclear bacteria confer beneficial effects to their hosts, such as an increased survival under adverse environmental conditions or protection against co-infection by cytoplasmic bacteria55,61,62. However, at the moment we have no indication that the symbiosis between Nucleophilum and its amoeba host is a mutualistic association. Genome analysis in combination with functional approaches, such as transcriptomics and proteomics, will help to gain insights into the infection process, interaction mechanisms, possible benefits for host and symbiont, and the evolution of this unique lifestyle.

This is the first report on the concomitant isolation and characterization of marine amoebae and their bacterial endosymbionts. The low degree of relationship of the symbionts to known bacteria and the discovery of a symbiont thriving in the host perinuclear space, a niche not reported previously for intracellular microbes, indicates that marine habitats represent a rich pool of hidden symbiotic associations.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schulz, F. et al. Marine amoebae with cytoplasmic and perinuclear symbionts deeply branching in the Gammaproteobacteria. Sci. Rep. 5, 13381; doi: 10.1038/srep13381 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a DOC fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences to F.S., by the Czech Science Foundation to T.T. and I.D. (grant 505/12/G112), by the Grant Agency of University of South Bohemia to T.T. (140/2013/P), by a European Research Council grant to M.H. (ERC grant ‘EvoChlamy’ #281633) and by a grant of the Austrian Science Fund (I1628-B22) to M.H. I.P. and S.F. contributions were supported by the National Flag program RITMARE (SP3-WP2-A2-UO5).

Footnotes

Author Contributions I.P., S.F., T.T. performed the sampling; F.S., T.T., I.D., M.K. and M.H. conceived the experiments; F.S., T.T., I.P. and M.K. conducted the experiments; F.S., T.T. and M.K. analyzed the results. All authors discussed and commented the results. F.S. and T.T. prepared figures; F.S., T.T. and M.H. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Rodríguez-Zaragoza S. Ecology of free-living amoebae. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 225–241 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N. A. Acanthamoeba: Biology and Pathogenesis. (Horizon Scientific Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Adl S. M. et al. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 59, 429–514 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. et al. Multigene phylogeny resolves deep branching of Amoebozoa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 293–304 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov A. V. in Encyclopedia of Microbiology. 558–577 (Elsevier, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Barker J. & Brown M. R. Trojan horses of the microbial world: protozoa and the survival of bacterial pathogens in the environment. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 140, 1253–1259 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greub G. & Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17, 413–433 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn M. & Wagner M. Bacterial endosymbionts of free-living amoebae. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 51, 509–514 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molmeret M., Horn M., Wagner M., Santic M. & Abu Kwaik Y. Amoebae as training grounds for intracellular bacterial pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 20–28 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Esser S. et al. Diversity of bacterial endosymbionts of environmental acanthamoeba isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5822–31 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagkouvardos I., Shen J. & Horn M. Improved axenization method reveals complexity of symbiotic associations between bacteria and acanthamoebae. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6, 383–388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnier I. et al. Babela massiliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae. Biol. Direct 10, 1–17 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn M. Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62, 113–31 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosetti N., Croxatto A. & Greub G. Amoebae as a tool to isolate new bacterial species, to discover new virulence factors and to study the host–pathogen interactions. Microb. Pathog. 77, 125–130 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzetti I., Fazi S., Fuchs B. M. & Amann R. High abundance of novel environmental chlamydiae in a Tyrrhenian coastal lake (Lago di Paola, Italy). Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 4, 446–452 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyková I. & Kostka M. Illustrated guide to culture collection of free-living amoebae. (Academia, 2013). at < http://www.muni.cz/research/publications/1091345> Accessed on 3rd July 2015.

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S. & Eliceiri K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daims H., Stoecker K. & Wagner M. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of prokaryotes. Mol. Microb. Ecol. 213, 239–239 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Amann R. & Binder B. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 1919–25 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daims H., Brühl A., Amann R., Schleifer K. H. & Wagner M. The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all Bacteria: development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22, 434–44 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W. et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1363–1371 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loy A. et al. probeCheck–a central resource for evaluating oligonucleotide probe coverage and specificity. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 2894–2898 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz L. S., Parnerkar S. & Noguera D. R. mathFISH, a web tool that uses thermodynamics-based mathematical models for in silico evaluation of oligonucleotide probes for fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1118–1122 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlin L., Elwood H. J., Stickel S. & Sogin M. L. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene 71, 491–499 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis D. M. & Dixon M. T. Ribosomal DNA: molecular evolution and phylogenetic inference. Q. Rev. Biol. 66, 411–453 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juretschko S. et al. Combined molecular and conventional analyses of nitrifying bacterium diversity in activated sludge: Nitrosococcus mobilis and Nitrospira-like bacteria as dominant populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiolgy 64, 3042–3051 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loy A., Lehner A. & Lee N. Oligonucleotide microarray for 16S rRNA gene-based detection of all recognized lineages of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5064–5081 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–42 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S., Gish W. & Miller W. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D. L. et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D13–21 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N., Lepage T. & Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 25, 2286–2288 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K. D., Tatusova T., Brown G. R. & Maglott D. R. NCBI Reference Sequences (RefSeq): current status, new features and genome annotation policy. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D130–D135 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farone A. L., Berk S. G., Farone M. B. & Gunderson J. H. The isolation and characterization of naturally-occurring amoeba-resistant bacteria from water samples. (2010). at < http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.highlight/abstract/8114/report/F> Accessed on 3rd July 2015.

- Page F. C. Fine-structure of some marine strains of Platyamoeba (Gymnamoebia, Thecamoebidae). Protistologica 16, 605–612 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov A. V., Nassonova E. S., Chao E. & Cavalier-Smith T. Phylogeny, evolution, and taxonomy of vannellid amoebae. Protist 158, 295–324 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsyuk M. New Gymnamoebae Species (Gymnamoebia) in the Fauna of Ukraine. Vestn. Zool. 46, e–7–e–13 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tekle Y. I. et al. Phylogenetic placement of diverse amoebae inferred from multigene analyses and assessment of clade stability within ‘Amoebozoa’ upon removal of varying rate classes of SSU-rDNA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 47, 339–352 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahr D. J. G., Grant J., Nguyen T., Lin J. H. & Katz L. A. Comprehensive phylogenetic reconstruction of amoebozoa based on concatenated analyses of SSU-rDNA and actin genes. PloS One 6, e22780 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro D., Pages G. S., Catalan V., Loret J.-F. & Greub G. Biodiversity of amoebae and amoeba-associated bacteria in water treatment plants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 213, 158–166 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delafont V., Brouke A., Bouchon D., Moulin L. & Héchard Y. Microbiome of free-living amoebae isolated from drinking water. Water Res. 47, 6958–6965 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walochnik J. et al. Discrimination between Clinically Relevant and Nonrelevant Acanthamoeba Strains Isolated from Contact Lens- Wearing Keratitis Patients in Austria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 3932–3936 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghsood A. H. et al. Acanthamoeba genotype T4 from the UK and Iran and isolation of the T2 genotype from clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 54, 755–759 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche T. R. et al. In situ detection of novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. phylogenetically related to members of the order Rickettsiales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 206–212 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn M., Fritsche T. R., Gautom R. K., Schleifer K.-H. & Wagner M. Novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the Paramecium caudatum symbiont Caedibacter caryophilus. Environ. Microbiol. 1, 357–367 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo J. et al. Survival and transfer ability of phylogenetically diverse bacterial endosymbionts in environmental Acanthamoeba isolates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 524–533 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoth F. & Greub G. Amoebal pathogens as emerging causal agents of pneumonia. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 260–280 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B. & Raoult D. Survival of Coxiella burnetii within free-living amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7, 75–79 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B. et al. Legionella drancourtii sp. nov., a strictly intracellular amoebal pathogen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54, 699–703 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. P. et al. Phylogeny of gammaproteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2305–14 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R. et al. Molecular characterization and evolution of arthropod-pathogenic Rickettsiella bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5045–5047 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. A., Driscoll T., Gillespie J. J. & Raghavan R. A Coxiella-like Endosymbiont is a potential vitamin source for the Lone Star Tick. Genome Biol. Evol. (2015). 10.1093/gbe/evv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima M. & Kodama Y. Endosymbionts in Paramecium. Eur. J. Protistol. 48, 124–37 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz F. & Horn M. Intranuclear bacteria: inside the cellular control center of eukaryotes. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 339–346 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel R., Hauroder B., Muller K. & Zoller L. An environmental Naegleria-strain, unable to form cysts-turned out to harbour two different species of endocytobionts. Endocytobiosis Cell Res. 118, 115–118 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Walochnik J., Muller K., Aspock H. & Michel R. An endocytobiont harbouring Naegleria strain identified as N. clarki De Jonckheere, 1994. Acta Protozool. 44, 301–310 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Schulz F. et al. Life in an unusual intracellular niche: a bacterial symbiont infecting the nucleus of amoebae. ISME J. 8, 1634–1644 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke A. J. M., Weiger T. M. & Matzke M. Ion channels at the nucleus: electrophysiology meets the genome. Mol. Plant 3, 642–652 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. C., Chung W. S., Yun D.-J. & Cho M. J. Calcium and calmodulin-mediated regulation of gene expression in plants. Mol. Plant 2, 13–21 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori M., Fujii K. & Fujishima M. Micronucleus-specific bacterium Holospora elegans irreversibly enhances stress gene expression of the host Paramecium caudatum. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 55, 515–21 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski F. U. et al. Widespread occurrence of an intranuclear bacterial parasite in vent and seep bathymodiolin mussels. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1150–1167 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagkouvardos I., Weinmaier T., Lauro F. M., Cavicchioli R., Rattei T. & Horn M. Integrating metagenomic and amplicon databases to resolve the phylogenetic and ecological diversity of the Chlamydiae. The ISME journal. 8, 115–125 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.