Abstract

Purpose

To test the hypothesis that blood–retinal barrier compromise is associated with the development of endogenous Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis.

Methods

To compromise the blood–retinal barrier in vivo, streptozotocin-induced diabetes was induced in C57BL/6J mice for 1, 3, or 5 months. Diabetic and age-matched nondiabetic mice were intravenously injected with 108 colony-forming units (cfu) of S. aureus, a common cause of endogenous endophthalmitis in diabetics. After 4 days post infection, electroretinography, histology, and bacterial counts were performed. Staphylococcus aureus–induced alterations in in vitro retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell barrier structure and function were assessed by anti–ZO-1 immunohistochemistry, FITC-dextran conjugate diffusion, and bacterial transmigration assays.

Results

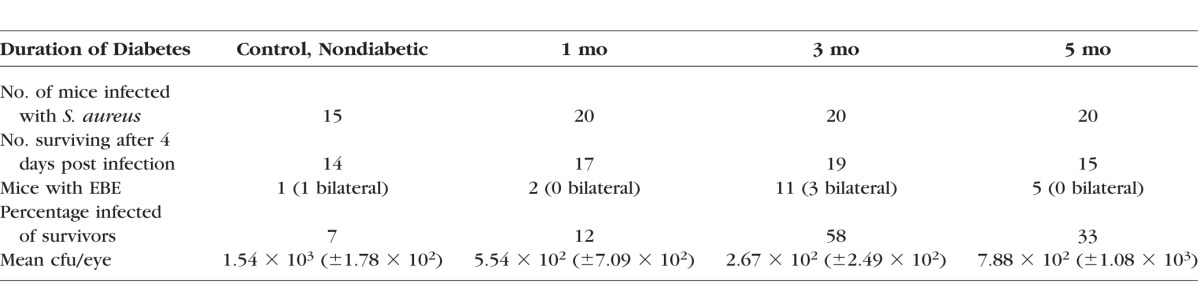

We observed one bilateral infection in a control, nondiabetic animal (mean = 1.54 × 103 ± 1.78 × 102 cfu/eye, 7% incidence). Among the 1-month diabetic mice, we observed culture-confirmed unilateral infections in two animals (mean = 5.54 × 102 ± 7.09 × 102 cfu/eye, 12% incidence). Among the 3-month diabetic mice, infections were observed in 11 animals, three with bilateral infections (mean = 2.67 × 102 ± 2.49 × 102 cfu/eye, 58% incidence). Among the 5-month diabetic mice, we observed infections in five animals (mean = 7.88 × 102 ± 1.08 × 103 cfu/eye, 33% incidence). In vitro, S. aureus infection reduced ZO-1 immunostaining and disrupted the barrier function of cultured RPE cells, resulting in diffusion of fluorophore-conjugated dextrans and transmigration of live bacteria across a permeabilized RPE barrier.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results indicated that S. aureus is capable of inducing blood–retinal barrier permeability and causing endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis in normal and diabetic animals.

Keywords: endogenous endophthalmitis, Staphylococcus aureus, bacteria, blood–retinal barrier, diabetes, retinal pigment epithelium

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE) is a potentially devastating infection resulting from the migration of blood-borne organisms across a compromised blood–ocular barrier and into the eye. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis comprises approximately 2% to 8% of all endophthalmitis cases1 and is one of the most harmful ocular infections owing to uniformly poor visual outcomes and the possibility of bilateral blindness. Most EBE patients have an underlying disease and/or are immunocompromised.2 These conditions include endocarditis, urinary tract infections, diabetes mellitus, the presence of indwelling central venous catheters, immunosuppressive therapy, and illicit intravenous drug abuse.3 Currently, diabetes mellitus ranks among the leading predisposing diseases for EBE and is associated with 33% of cases.1,4–7

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for nearly 10% of EBE cases worldwide1 and is the leading cause of EBE in the Western hemisphere and Europe, comprising approximately 25% of these cases.1–3 In the United States, approximately 40% of EBE cases are associated with endocarditis, which is usually caused by S. aureus.3 Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive bacterium that normally colonizes the skin and mucosa but can cause mucosal and submucosal infections, and life-threatening systemic infections, including septicemia, endocarditis, and pneumonia.8,9 Staphylococcus aureus EBE is also frequently associated with infection of indwelling catheters and prosthetic devices in diabetics and the immunocompromised.1,7–12

Presently, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections are a public health emergency owing to the refractory nature of these multidrug-resistant infections. It has been estimated that greater than 50% of S. aureus isolates from health care settings are methicillin-resistant.2 MRSA infections among persons with functioning immune systems are being reported with increasing frequency.13 Paralleling the rise in the frequency of MRSA infections is an increase in the number of MRSA endophthalmitis cases.10,14 Major et al.10 have reported that MRSA strains account for 41% of all types of endophthalmitis caused by S. aureus and cause a similar percentage of cases of S. aureus EBE. Moreover, this group has found that among the MRSA isolates, approximately 38% are also resistant to commonly used fourth-generation fluoroquinolones (gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin) used to treat ocular infections.10 Case studies have revealed that only 24% to 38% of MRSA EBE infections result in a final visual acuity better than 20/200.2 Visual acuity outcomes of S. aureus EBE are consistently poor. However, no difference between the final Snellen visual acuity of MRSA- and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus–infected eyes has been observed.10

Currently, a limited understanding exists regarding the interactions between the host and bacterial factors that contribute to the development of EBE. The factors contributing to the migration of S. aureus into the eye resulting in EBE have not been analyzed. It has been suggested that diabetes ranks among the leading underlying factors associated with EBE because of the immunologic and architectural changes in the eye that occur during the progression of diabetes.6,15–17 These changes include increases in vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in diabetic retinas that lead to angiogenesis and a breakdown in the blood–retinal barrier (BRB).18 Further, increases in neutrophil adhesion to the endothelial wall due to upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and CD18 lead to endothelial cell injury and death.19–22 Architecturally, pericyte death and basement membrane thickening lead to capillary leakage and occlusion. These changes ultimately result in macular edema, angiogenesis, and neuroretinal degeneration.18–28 Collectively, these alterations in the diabetic ocular environment could compromise the eye's ability to prevent bacteria from entering during systemic infection.

Until recently, the lack of an animal model of EBE has been largely responsible for the gaps in information on the role of bacterial and host factors in the development of EBE. We have developed a murine model of diabetes-associated Klebsiella pneumoniae EBE and reported a correlation between the time from diabetes induction with streptozotocin (STZ) and the incidence of EBE.17 Further, the observed increase in infection incidence also correlates with increases in BRB permeability that occur in mice with more advanced diabetes.17 In the current study, we extended the use of our mouse model to address the hypothesis that diabetic ocular changes coincided with an increase in incidence in S. aureus EBE. Here, we showed a correlation between diabetes development and the incidence of S. aureus EBE, and further demonstrated that S. aureus possesses the capacity to cause EBE in nondiabetic, normal eyes without preexisting vascular leakage. We also showed that S. aureus is capable of inducing alterations in the tight junctions between human retinal epithelial (RPE) cells in vitro and traversing an intact RPE barrier. In conjunction with our in vivo infection data, these results support the hypothesis that the BRB compromise in diabetic mice contributes to the development of EBE and that S. aureus is capable of inducing BRB permeability on its own, causing EBE in normal and diabetic animals.

Methods

Animals

Six-week-old C57BL/6J mice were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and used in accordance with institutional guidelines and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice were allowed to adjust to conventional housing 2 weeks before the establishment of diabetes. Mice were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of 85 mg/kg ketamine and 14 mg/kg xylazine before tail-vein injections and electroretinography.

Streptozotocin Induction of Diabetes

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were given two STZ injections of 100 mg/kg, 1 week apart.17 Streptozotocin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) was solubilized in freshly prepared 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.5) and immediately intraperitoneally injected. Blood glucose levels were quantified 2 weeks after the second STZ injection and were greater than or equal to 400 mg/dL for all mice. Infections were initiated at 1, 3, or 5 months post STZ injection. Mice were the same age (28 weeks) at the time of infection. Age-matched control animals were administered citrate buffer pH 4.5 only. Before injections with S. aureus, blood glucose levels were assessed again to ensure the establishment of diabetes in all mice.

S. aureus EBE Model

We used S. aureus strain 8325-4 for our studies. Strain 8325-4 is a well-characterized prophage- and plasmid-free strain derived from the clinical isolate 8325.29 This strain has been used to initiate experimental endophthalmitis in rabbits and mice.30–32 Strain 8325-4 was grown for 18 hours in brain heart infusion media (BHI; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA), and subcultured in prewarmed BHI to logarithmic phase. Bacteria were then centrifuged and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis was established by injecting mice via the tail vein with 108 colony-forming units (cfu) in 100 μL PBS. At 4 days post infection, the retinal function of both eyes from mice in each group was measured by electroretinography (ERG). After ERG, both eyes from each mouse were harvested for bacterial quantitation or histology.

Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis

Mice were dark adapted for 6 hours and then anesthetized as described above. Pupils were dilated with 10% topical phenylephrine (Acorn, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and gold-wire electrodes were placed over both corneas with a drop of GONAK (Hypromeliose Ophthalmic Demulscen Solution 2.5%; Akorn, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) to ensure maximum conductance. Scotopic ERGs were recorded for both eyes (Diagnosys LLC, Littleton, MA, USA). The A-wave amplitude was measured from the prestimulus baseline to the A-wave trough, and the B-wave amplitude was measured from the A-wave trough to the B-wave peak. Percentage ERG retention was calculated relative to mean baseline ERGs recorded from six eyes per group before infection, as previously described.17,33,34

Bacterial Quantitation

For each group of infected mice, eyes were selected at random for bacterial quantitation. Briefly, both eyes from each mouse selected were enucleated, placed into separate tubes containing 400 μL sterile PBS and 1.0-mm sterile glass beads (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA), and homogenized for 60 seconds at 5000 rpm in a Mini-BeadBeater (Biospec Products, Inc.). Eye homogenates were serially diluted and plated in triplicate on tryptic soy agar + 5% sheep erythrocyte and mannitol salt agar plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the colony-forming units per eye was determined as previously described.17,33,34

Histology

Homogenization of eyes for bacterial quantitation precludes histologic analysis on eyes that are confirmed as culture positive. Eyes from each group were randomly selected and fixed in Excalibur's Alcoholic Z-Fix (Excalibur Pathology, Inc., Norman, OK, USA) for 24 hours, and then embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and tissue Gram stain as previously described.17,33,34

Human RPE Cell Culture

Human ARPE-19 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were propagated and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies).35 Cells were grown to confluence, diluted in culture medium, and seeded in sterile 12-well plates containing transwells and 24-well plates containing glass coverslips. Transwells (0.4 or 8 μm; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were prepared by coating with coating solution (10 mL DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS, 13.6 μL bovine serum albumin 7.5% (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 μL bovine type I collagen (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), and 100 μL human fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Glass coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were prepared in an analogous manner. After coating, the transwells and coverslips were washed once with PBS and seeded with 200 μL 2.5 × 105 cells/mL or 400 μL 2.5 × 105 cells/mL, respectively, in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS. Monolayer formation and tight junction integrity was confirmed by immunocytochemistry and a dextran-fluorophore conjugate diffusion assay as described in detail below.

Human RPE Infection by S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus strain 8325-4 was grown for 18 hours in BHI medium, washed with PBS, and diluted into RPE cell culture medium. Tissue culture wells with either glass coverslips or transwells were inoculated with the bacterial suspension to achieve a final concentration of 104 cfu/mL. This represents a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02, or 1 bacterial cell per 50 RPE cells on the coverslips, and an MOI of 0.01, or 1 bacterial cell per 100 RPE in the transwells. Following infection, bacterial growth was assessed at 2-hour intervals thereafter. Strain 8325-4 achieves concentrations of approximately 2.0 × 108 cfu/mL at 8 hours post inoculation. Mock, uninfected coverslips or transwells received RPE cell culture medium only. To determine if the effects on human RPE cells were specific to S. aureus, a hypermucoviscosity (HMV)–deficient strain of K. pneumoniae17 was also grown for 18 hours in BHI, washed with PBS, and diluted into RPE cell culture medium. Tissue culture wells with glass coverslips were inoculated with K. pneumoniae to achieve a final concentration of 104 cfu/mL (MOI = 0.02). After infection, bacterial growth was assessed at 2-hour intervals, and K. pneumoniae reached approximately 5.0 × 108 cfu/mL at 8 hours post inoculation.

Immunocytochemistry

Uninfected and infected RPE monolayers on coverslips were fixed in 100% methanol at −80°C for 30 minutes. Coverslips were incubated once in TBS + 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, followed by Protein Block (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Anti–ZO-1 antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added to a final concentration of 15 μg/mL. The anti–ZO-1 antibody was removed and the coverslips were washed three times with PBS + 0.001% Tween 20. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA) was added and coverslips were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. After three washes with PBS + 0.001% Tween 20, coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Vectashield Hard Set and stained with DAPI (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) and imaged with an Olympus Confocal FV500 microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA, USA). The fluorescence intensity of ZO-1 staining at the periphery of individual RPE cells was quantified by using ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).36–38 Briefly, N ≥ 10 random confocal images were taken per group and N = 5 cells were chosen at random from each confocal image. The edge of each cell was traced and a plot profile of intensity for each trace was generated (approximately 500–1000 points per trace). The percentage ZO-1 immunopositivity for each cell was calculated as the fraction of points greater than 25% of the maximum intensity for each cell. Percentages for each group were averaged and are presented as the mean ± SD for N ≥ 10 images per group (mock versus bacteria at 4, 6, or 8 hours post infection).

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)–Dextran Conjugate Diffusion Assay

To measure the degree of permeability of human RPE cell culture monolayers after infection with S. aureus 8325-4, the diffusion of FITC-dextran conjugates (4 kDa or 70 kDa) were assessed by fluorescence spectrophotometry. Monolayers were cultured on 0.4-μm transwells and infected with 104 cfu/mL in RPE cell culture medium or medium alone for 4, 6, or 8 hours post infection. Addition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) to a final concentration of 30% for 30 minutes permeabilized the monolayers and functioned as a positive control. The FITC-dextran conjugates at 1 mg/mL were added to the transwells at each time point and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured in the lower chamber by fluorescence spectroscopy, and the concentration of FITC-dextran conjugate that diffused across the monolayer was calculated from a standard curve of known concentrations. Values are expressed as the mean FITC-dextran conjugate concentration ± SEM of N ≥ 4 measurements per time point.

Transmigration of S. aureus Across Human RPE Monolayers

To assess the degree of transmigration of S. aureus across an intact RPE monolayer, RPE monolayers in 8.0-μm transwells were infected as described above, and the medium in the lower chamber was removed and quantified by plating at 4, 6, and 8 hours post infection. At each time point, fresh, prewarmed RPE cell culture medium was added to replace the medium in the lower chamber. As a positive control, pretreatment of the RPE monolayers with 0.25% Triton X-100 was used to disrupt the RPE barrier, facilitating free diffusion of S. aureus across the transwell membranes.

Statistics

All values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the bacterial counts in infected eyes, FITC-dextran conjugate concentrations, and in vitro bacterial counts. A 2-tailed Fisher's exact test was used to assess significance between the incidence of EBE among the control and diabetic groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess levels of significance in the ZO-1 immunopositivity assay. Two-tailed, 2-sample t-tests were used for statistical comparisons between groups for all other in vitro assays. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Diabetes and Incidence of S. aureus EBE

To examine the link between diabetes progression and the development of S. aureus EBE, we used our mouse model of STZ-induced diabetes.17 As shown in the Table, 4 days following infection with 108 cfu of S. aureus strain 8325-4, we observed one culture-confirmed infected mouse in the control, nondiabetic group. In this animal, both the right and left eyes were infected, with a mean of 1.54 × 103 ± 1.78 × 102 cfu per eye. Among the 1-month diabetic mice, we observed culture-confirmed infections in two animals. Only the left eye in each of these animals was infected (mean = 5.54 × 102 ± 7.09 × 102 cfu per eye). The infection incidence was 7% and 12% for the control nondiabetic and 1-month diabetic mice, respectively. In the 3-month diabetic group, infections were culture confirmed in 11 different animals, with three animals having bilateral infections. A total of eight right eyes and six left eyes were infected, with a mean of 2.67 × 102 ± 2.49 × 102 cfu per eye (58% infection incidence). Allowing diabetes to progress for 5 months, we observed culture-confirmed infections in five animals (four right eyes and one left eye) for a mean of 7.88 × 102 ± 1.08 × 103 cfu per eye (33% infection incidence).

Table.

Incidence of S. aureus EBE at 4 Days Post Infection in Control, Nondiabetic and STZ-Induced Diabetic (1- , 3- , and 5-Months' Duration) Mice Infected With S. aureus Strain 8325-4

These results showed no significant difference between the control, nondiabetic group and the 1-month diabetic group in EBE incidence (Table) (P = 1.0). However, we observed a statistically significant increase in the incidence of S. aureus EBE from 1 month to 3 months following diabetes induction (Table) (P = 0.0058). While the incidence of EBE appeared to decline between 3 and 5 months, there was no significant difference between these two groups (P = 0.1854). In this EBE model, intravenous infection with S. aureus strain 8325-4 resulted in a higher incidence of intraocular infection than did the HMV− strain of K. pneumoniae, tested previously.17 Moreover, these results also suggest that S. aureus is able to migrate into the eye in the absence of (control mice) or during the early stages of (1 month) architectural and immunologic changes that occur during the development and progression of diabetes.

Retinal Function and Inflammation During S. aureus EBE

To determine whether retinal function was altered as a result of EBE, ERG was performed 4 days after S. aureus infection. There were no significant changes compared to preinfection baseline retinal function among any animals in any of the infection groups. There were no significant differences in the percentage A- or B-wave amplitudes retained among the animals in the nondiabetic and the 1-, 3-, or 5-month diabetic groups that were culture confirmed with S. aureus EBE (data not shown). Staining of sections with hematoxylin-eosin and tissue Gram stain did not reveal any significant polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) infiltration (data not shown). These findings were similar to what we observed following infection with the HMV− strain of K. pneunomiae.17

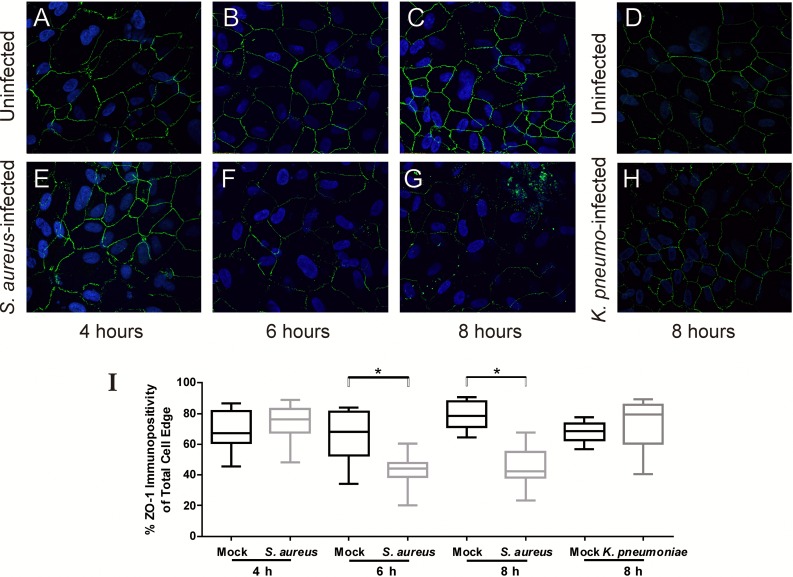

S. aureus Causes Alterations in Human RPE Tight Junctions In Vitro

From our observations of intraocular infections in control, nondiabetic and 1-month diabetic mice, as well as a higher incidence among 3- and 5-month diabetic mice relative to what we previously observed with K. pneumoniae in this model,17 we hypothesized that S. aureus contributes to the pathogenesis of EBE by inducing permeability changes in in vitro barriers formed by the RPE. We first determined whether S. aureus caused alterations in immunostaining patterns of the tight junction ZO-1 protein at the borders between cultured human RPE cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that ZO-1 immunoreactivity was localized to the borders between cells in the uninfected RPE monolayers at all time points examined (Figs. 1A–D), and at 4 hours after infection with S. aureus (Fig. 1E). However, markedly reduced ZO-1 staining was observed in RPE cells infected with S. aureus beginning at 6 hours post infection (Fig. 1F) and was further reduced at 8 hours after infection (Fig. 1G). In Figure 1I, immunopositivity of randomly selected cells was significantly lower that the immunopositivity of mock-infected RPE cells at 6 hours (P = 0.0054) and 8 hours (P < 0.0001) post infection, but not at 4 hours post infection (P = 0.1318). Infection of RPE cells with an HMV-deficient strain of K. pneumoniae17 did not reveal significant alterations in ZO-1 staining relative to mock-infected cells (Figs. 1D, 1H, 1I; P = 0.1841), indicating that the observed alterations are not due to a generalized phenomenon of bacterial growth and that K. pneumoniae cannot alter RPE tight junctions within the time frame of this experiment. The RPE cellular viability was assessed at each time point by trypan blue staining and was 98.7% at 4 hours, 98.4% at 6 hours, and 97.6% at 8 hours, thus ruling out the possibility that these changes were secondary to the death of these cells. This significant reduction in immunoreactivity of ZO-1 after inoculation with S. aureus indicated a disruption in expression and/or organization of ZO-1 in the tight junctions between RPE cells and demonstrated that S. aureus was capable of altering the tight junctions between RPE cells in vitro. Taken together, these results support the observation that the increased incidence of S. aureus EBE relative to K. pneumoniae EBE correlates with the ability of S. aureus to alter RPE tight junctions.

Figure 1.

Staphylococcus aureus induces alterations in ZO-1 immunoreactivity in cultured human RPE cells. Intact monolayers of human RPE cells were infected with S. aureus 8325-4 at a concentration of 104 cfu/mL (MOI = 0.02), stained with anti–ZO-1, and analyzed by immunofluorescence. (A–D) Uninfected RPE cells. (E–G) Retinal pigment epithelial cells at 4, 6, and 8 hours following infection with S. aureus. (H) Retinal pigment epithelial cells at 8 hours following infection with K. pneumoniae. (A–H) ×10 magnification. (I) Results of the quantitative analysis of ZO-1 staining. The y-axes represent % immunopositivity for anti–ZO-1 from five randomly selected cells from each of N ≥ 10 separate fields (6-hour mock-infected RPE cells versus S. aureus infected, P = 0.0007; 8-hour mock-infected RPE cells versus S. aureus infected, P < 0.0001).

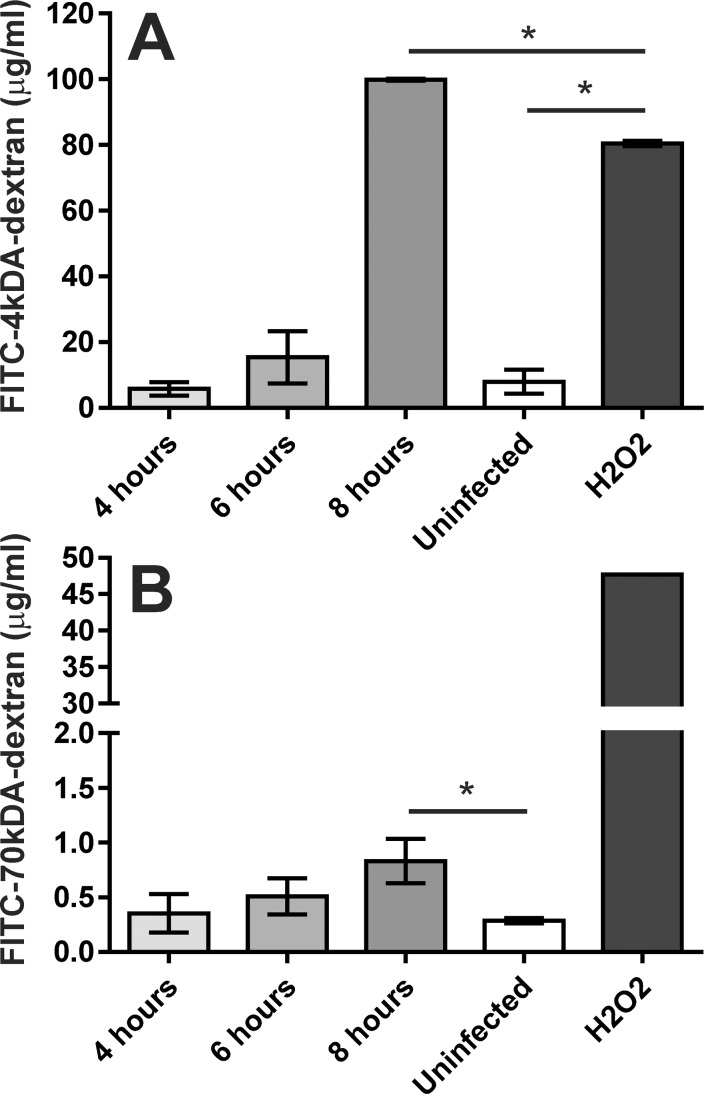

S. aureus Induces Barrier Function Changes in Cultured Human RPE Cells

We next assessed whether these observed changes in ZO-1 immunoreactivity correlated with changes in the barrier function of these monolayers. Analysis of the diffusion of the FITC-dextran conjugates across an RPE barrier after infection with S. aureus revealed a time-dependent increase in the concentration of these conjugates in the lower chamber (Figs. 2A, 2B). There was no statistically significant difference between the concentrations of either of the FITC-dextran conjugates in the lower chamber of wells infected with S. aureus and uninfected wells at 4 hours (P = 0.4 for the 4-kDa FITC-dextran conjugate; P = 0.6 for the 70-kDa FITC-dextran conjugate) or at 6 hours (P = 0.06 and P = 0.1, respectively). However, significantly higher concentrations of FITC-dextran conjugates were observed in the lower chamber of wells infected with S. aureus at 8 hours than in uninfected RPE monolayers (P < 0.0001 for the 4-kDa FITC-dextran conjugate; P = 0.01 for the 70-kDa FITC-dextran conjugate) (Fig. 2). The diffusion of the 4-kDa fluorophore-conjugate was significantly higher across RPE monolayers after infection with S. aureus for 8 hours than for RPE monolayers treated with H2O2 for the same amount of time (P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Staphylococcus aureus alters the permeability of cultured RPE cells to fluorophore-conjugated dextrans. Intact monolayers of human RPE cells in 0.4-μm transwells were infected with S. aureus 8325-4 at a concentration of 104 cfu/mL (MOI = 0.01), and diffusion of 4-kDa FITC- dextran (A) and 70-kDa FITC-dextran (B) across the monolayer was assessed by fluorescence spectrometry of the bottom chamber at 4, 6, and 8 hours after bacterial inoculation of the top chamber. No significant differences were observed between the uninfected wells and infected wells after 4 and 6 hours. However, after 8 hours the fluorescence intensity in the bottom chamber was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than in the uninfected groups. Values represent the mean concentration of the conjugate in the bottom chamber ± SD (N ≥ 3 at each time point), based on extrapolation from a standard curve of the fluorimetry of known FITC-dextran concentrations.

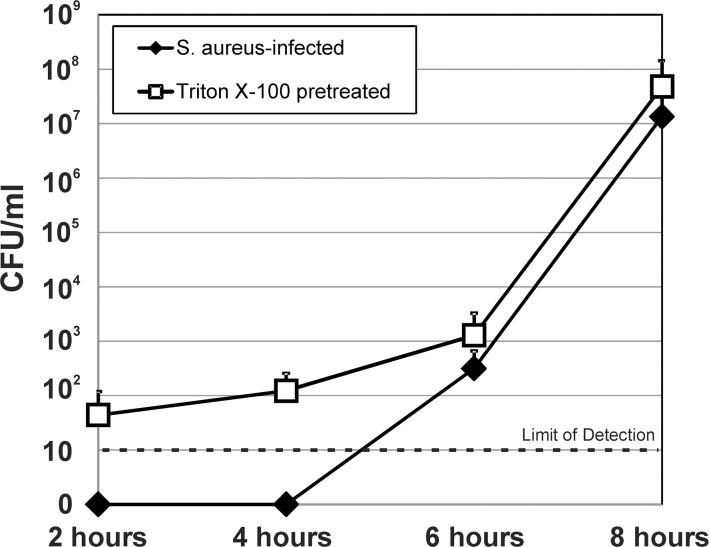

For bacterial transmigration, we evaluated the concentration of S. aureus in lower chamber after infection (Fig. 3). After inoculation of the upper chamber with S. aureus, bacterial counts in the lower chamber were below the limit of detection (10 cfu/mL) after 2 and 4 hours post inoculation. At 6 hours, the concentration of S. aureus in the bottom chamber was 3.15 × 102 (±3.45 × 102) cfu/mL, and at 8 hours, S. aureus reached 1.34 × 107 (±2.54 × 107) cfu/mL. The 6- and 8-hour concentrations were primarily the result of transmigration of bacteria across the disrupted monolayer, as there was only a 2-hour window for replication to occur after complete removal of the media in the lower chamber at the previous time point. Pretreatment of RPE monolayers with Triton X-100 to obliterate the cellular barrier resulted in detectable bacteria in the lower chamber at all time points, with 4.77 × 107 (±9.49 × 107) cfu/mL at 8 hours post infection (P = 0.5 versus S. aureus infection alone without pretreatment with Triton X-100). Collectively, these results showed that S. aureus disrupts the RPE monolayer in vitro, resulting in the diffusion of both fluorophore-conjugated dextrans and live bacteria across a permeabilized barrier. These results provided in vitro support of our hypothesis that S. aureus might directly contribute to EBE pathogenesis by compromising the barrier function of the RPE component of the outer BRB.

Figure 3.

Staphylococcus aureus alters the permeability of cultured RPE cells to live bacteria. Intact monolayers of human RPE cells in 8.0-μm transwells were infected with S. aureus 8325-4 at a concentration of 104 cfu/mL (MOI = 0.01), and diffusion of bacteria across the monolayer was assessed by removing the entire contents of the bottom chamber and replacing with fresh cell culture medium at 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours after inoculation of the top chamber. Pretreatment of RPE monolayers with Triton X-100 to obliterate the cellular barrier resulted in detectable bacteria in the lower chamber at all time points, with 4.77 × 107 (±9.49 × 107) cfu/mL at 8 hours post infection, and was not significantly different from S. aureus infection alone without pretreatment with Triton X-100 (P = 0.5). Values represent the mean concentration of S. aureus in the bottom chamber ± SD (N ≥ 3 at each time point).

Discussion

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis is a potentially blinding disease that is linked to a number of underlying conditions, with diabetes ranking as one of the primary risk factors for contracting EBE.1,4–7 During the progression of diabetes, changes in the vascular architecture occur that result in the breakdown and increased permeability of the BRB. We hypothesized that compromise of the blood–retinal barrier created a favorable environment for blood-borne pathogens to enter the eye. To understand the link between diabetes development and the increased risk of contracting EBE, we have previously evaluated the frequency of K. pneumoniae EBE in STZ-induced diabetic mice.17 No EBE is observed in infected 1-month diabetic and age-matched nondiabetic control mice. A 24% and 27% incidence of K. pneumoniae EBE is observed in mice with diabetes of 3- and 5-months' duration, respectively, but no EBE among control, age-matched nondiabetic mice.17 The rise in EBE occurrence parallels the increase in vascular permeability in the 3- and 5-month diabetic mice. These results support our hypothesis that ocular environmental changes occurring during diabetes progression facilitate the development of K. pneumoniae EBE. Both the EBE model and the intravitreal injection model of bacterial endophthalmitis enable the qualitative and quantitative analysis of different phases of disease initiation, development, and visual outcome.17

In the current study, we used the STZ-induced diabetic mouse model to determine if S. aureus EBE incidence correlated with the duration of diabetes and observed a 58% and 33% incidence of S. aureus EBE among 3- and 5-month diabetic mice, respectively. While the incidence of S. aureus EBE among 5-month diabetic mice was similar to what we observed previously for K. pneumoniae EBE, the incidence of S. aureus among 3-month diabetic mice was 2.5-fold higher than what we observed for K. pneumoniae. In contrast to our findings of no infections in control, nondiabetic and 1-month diabetic mice after tail-vein injection with K. pneumoniae, we observed a 7% and a 12% incidence of S. aureus EBE in control nondiabetic and 1-month diabetic mice, respectively. These results suggested that S. aureus strain 8325-4 was more virulent than the HMV− strain of K. pneumoniae tested previously in this model. Moreover, our results also suggest that S. aureus is able to invade the eye regardless of the degree of the blood–ocular barrier integrity. Staphylococcus aureus typically produces a myriad of cytolytic toxins, while K. pneumoniae does not.

Similar to our results in the K. pneumoniae EBE model,17 we did not observe significant differences in the retinal function retention among the animals in the nondiabetic and the 1-, 3-, or 5-month diabetic groups that were culture confirmed with S. aureus EBE. We also did not observe significant inflammation in eyes culture confirmed with S. aureus EBE. In our direct injection models of endophthalmitis, several orders of magnitude higher concentrations of intraocular bacteria are necessary to affect substantial declines in retinal function and significant intraocular inflammation.21,39,40

Our observations in the experimental S. aureus EBE model raised the prospect that S. aureus itself might contribute to the degradation of the BRB. The RPE constitutes a component of the outer BRB that could potentially serve as a portal of entry for bacteria in the choroidal vasculature. To evaluate the hypothesis that S. aureus might contribute to EBE pathogenesis by altering the barrier function of the RPE component of the outer BRB, we examined immunostaining patterns of the zonula occludens ZO-1 protein component of tight junctions between cultured human RPE cells in vitro. Staphylococcus aureus infection caused alterations in ZO-1 immunoreactivity at the borders between cultured human RPE cells. Disruption of ZO-1 staining correlated with increases in the permeability of RPE monolayers to FITC-conjugated dextrans and to live bacteria. Moyer et al.35 also have found that Bacillus cereus increases barrier permeability of RPE monolayers in vitro in a similar time frame. Losses in ZO-1 staining are observed 8 hours after infection with B. cereus, and changes in permeability to FITC-dextran are observed as early as 2 hours following infection.35 Our in vitro results support our observations in the mouse model of S. aureus EBE and suggest that S. aureus can directly contribute to EBE development by disrupting the barrier function of the RPE, creating portals for entry into the eye.

Staphylococcus aureus expresses as many as 20 different adhesins and microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules,41,42 including fibronectin-binding proteins FnbpA and FnbpB,43 the fibrinogen-binding proteins ClfA and ClfB,44 and the collagen-binding protein Cna.45 These factors mediate S. aureus adherence to extracellular matrix and plasma proteins, an important initial event in the establishment of infection. These adhesins have been implicated in a model of staphylococcal keratitis.46–48 Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan induces ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on the surface of endothelial cells.49 Moreover, subdomains of S. aureus FnbpA induce increases in ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and IL-8 from cultured endothelial cells.50 FnbpA, as well as the extracellular adherence protein, mediates adherence to and invasion of endothelial cells.51,52 It is possible that S. aureus contributes to the pathogenesis of EBE by inducing upregulation of vascular adhesion molecules and subsequent increases in vascular permeability. Systemic S. aureus infection might cause vascular permeability through the localized production of TNF-α, as S. aureus peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid have been shown to provoke TNF-α secretion.53 Injection of TNF-α into the vitreous of rabbits results in barrier breakdown, increased permeability, and cellular infilitration.54 These observations together might explain the significantly higher rate of S. aureus EBE than K. pneumoniae EBE in our diabetic mouse model.

Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4 also secretes a number of toxins that might play a role in EBE pathogenesis, including α-, β-, γ-, and δ-toxins and the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL).55–57 These toxins may directly cause structural damage to tissues in the eye, or, in the case of PVL, have either anti- or proinflammatory effects. The S. aureus α- and β-toxins have both been directly demonstrated to contribute to experimental endophthalmitis in rabbits.30,31 Panton-Valentine leukocidin can lyse neutrophils but can also effect the release of proinflammatory cytokines at low concentrations from these cells.58 While PVL can induce rapid cell death in human neutrophils, this toxin is not active against mouse PMNs59 and therefore would not have altered PMN function, potentially interfering with clearance from the eye. Hyaluronidase, a secreted enzyme that degrades hyaluronic acid and is postulated to promote tissue invasion,60 might also play a role in EBE pathogenesis. Hyaluronidase recently has been shown to be CodY regulated, and in a murine pulmonary model, concentrations of a hyaluronidase mutant are reduced by four orders of magnitude in lung tissue, lung tissue pathology is lessened, and levels of pulmonary hyaluronic acid are increased.60 Staphylococcal toxins may also contribute to EBE pathogenesis by interacting with and disrupting components of the BRB, thus creating portals of invasion for S. aureus in the vasculature of the eye.

Some strains of S. aureus are more virulent in animal models of sepsis because these isolates possess a capsule.61,62 Most S. aureus clinical isolates produce type 5 or type 8 capsular polysaccharide.63 Strain 8325-4 is type 564 but has no noticeable capsule when grown in vitro. Encapsulation may prevent clearance of S. aureus from the bloodstream or the vitreous humor, particularly if clearance mechanisms are compromised in the diabetic ocular environment. It is currently unknown whether adhesins, secreted factors, or the capsule might contribute to crossing the BRB and invasion of the eye. Future studies will address the effect of staphylococcal factors in facilitating infection in our model.

In summary, we identified an association between the STZ-induced diabetic murine ocular environment, specifically blood–retinal barrier compromise, and the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae and S. aureus EBE. This model also highlighted the ability of S. aureus to breach the BRB regardless of BRB integrity. Future studies will identify the mechanisms of EBE pathogenesis, specifically identifying the host and bacterial factors that contribute to this disease with a view toward developing more effective therapies. Our model suggests that S. aureus can cause infection in normal, nondiabetic animals, raising the possibility that S. aureus could potentially result in EBE in otherwise normal septic patients. Increased vigilance should therefore be practiced among diabetic patients with culture-confirmed S. aureus bacteremia, but also among normal septic patients with culture-confirmed S. aureus infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frederick Miller, PhD, and Austin LaGrow (Oklahoma Christian University, Edmond, OK, USA), and Madhu Parkunan and Nanette Wheatley (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center) for intellectual discussions and technical assistance. We also thank Excalibur Pathology, Inc. (Norman, OK, USA) for preparation of eye histology.

Presented in part at the annual conference of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Orlando, Florida, United States, May 4–8, 2014.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01EY024140 and R21EY022466 (MCC). Our research is also supported in part by NIH Grants R01EY012985 (MCC), P30EY21725 (NIH CORE grant to Robert E. Anderson, OUHSC), and an unrestricted grant to the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Disclosure: P.S. Coburn, None; B.J. Wiskur, None; R.A. Astley, None; M.C. Callegan, None

References

- 1. Jackson TL,, Paraskevopoulos T,, Georgalas I. Systematic review of 342 cases of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014. ; 59: 627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ho V,, Ho LY,, Ranchod TM,, Drenser KA,, Williams GA,, Garretson BR. Endogenous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Retina. 2011. ; 31: 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durand ML. Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013. ; 19: 227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arevalo J,, Jap A,, Chee S,, Zeballos D. Endogenous endophthalmitis in the developing world. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010; 50: 173–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenwald MJ,, Wohl LG,, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986. ; 31: 81–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson TL,, Eykyn SJ,, Graham EM,, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003. ; 48: 403–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Okada AA,, Johnson RP,, Liles WC,, D'Amico DJ,, Baker AS. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101: 832–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu GY. Molecular pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infection. Pediatr Res. 2009. ; 65: 71R–77R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 520–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Major JC,, Jr, Engelbert M,, Flynn HW,, Jr, Miller D,, Smiddy WE,, Davis JL. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010. ; 149: 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ness T,, Schneider C. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Retina. 2009. ; 29: 831–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nixdorff NA,, Tang J,, Mourad R,, Skalweit MJ. SAME is different: a case report and literature review of Staphylococcus aureus metastatic endophthalmitis. South Med J. 2009. ; 102: 952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gorak EJ,, Yamada SM,, Brown JD. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized adults and children without known risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. ; 29: 797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blomquist PH. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections of the eye and orbit [American Ophthalmological Society thesis]. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006; 104: 322–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wong TY,, Chiu SI,, So MK,, et al. Septic metastatic endophthalmitis complicating Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in a non-diabetic Chinese man. Hong Kong Med J. 2001. ; 7: 303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tan YM,, Chee SP,, Soo KC,, Chow P. Ocular manifestations and complications of pyogenic liver abscess. World J Surg. 2004. ; 28: 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coburn PS,, Wiskur BJ,, Christy E,, Callegan MC. The diabetic ocular environment facilitates the development of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012. ; 53: 7426–7431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jo DH,, Kim JH,, Kim JH. How to overcome retinal neuropathy: the fight against angiogenesis-related blindness. Arch Pharm Res. 2010. ; 33: 1557–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schroder S,, Palinski W,, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Activated monocytes and granulocytes capillary nonperfusion, and neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 1991. ; 139: 81–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miyamoto K,, Hiroshiba N,, Tsujikawa A,, Ogura Y. In vivo demonstration of increased leukocyte entrapment in retinal microcirculation of diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998. ; 39: 2190–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyamoto K,, Khosrof S, Bursell SE, et al. Prevention of leukostasis and vascular leakage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic retinopathy via intercellular adhesion molecule-1 inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; 96: 10836–10841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Funatsu H,, Yamashita H,, Sakata K,, et al. Vitreous levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 are related to diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2005. ; 112: 806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fong DS,, Aiello L,, Gardner TW,, et al. American Diabetes Association: diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26: 226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neely KA,, Gardner TW. Ocular neovascularization: clarifying complex interactions. Am J Pathol. 1998. ; 153: 665–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qaum T,, Xu Q,, Joussen AM,, et al. VEGF-initiated blood-retinal barrier breakdown in early diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001. ; 42: 2408–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takeda M,, Mori F,, Yoshida A,, et al. Constitutive nitric oxide synthase is associated with retinal vascular permeability in early diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 2001. ; 44: 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asnaghi V,, Gerhardinger C,, Hoehn T,, Adeboje A,, Lorenzi M. A role for the polyol pathway in the early neuroretinal apoptosis and glial changes induced by diabetes in the rat. Diabetes. 2003. ; 52: 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martin PM,, Roon P,, Van Ells TK,, Ganapathy V,, Smith SB. Death of retinal neurons in streptozotocin induced diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004. ; 45: 3330–3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Novick R. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology. 1967; 33: 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Booth M,, Atkuri R,, Nanda S,, Iandolo J,, Gilmore M. Accessory gene regulator controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995. ; 36: 1828–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Callegan M,, Booth M,, Jett B,, Gilmore M. Pathogenesis of gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1999. ; 67: 3348–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Engelbert M,, Gilmore M. Fas ligand but not complement is critical for control of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005. ; 46: 2479–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramadan RT,, Ramirez R,, Novosad BD,, Callegan MC. Acute inflammation and loss of retinal architecture and function during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res. 2006. ; 31: 955–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ramadan RT,, Moyer AL,, Callegan MC. A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008. ; 49: 4482–4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moyer AL,, Ramadan RT,, Thurman J,, Burroughs A,, Callegan MC. Bacillus cereus induces permeability of an in vitro blood-retina barrier. Infect Immun. 2008. ; 76: 1358–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rasband WS. ImageJ. . Bethesda MD: National Institutes of Health. 1997–2014. Available at: http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- 37. Schneider CA,, Rasband WS,, Eliceiri KW. NIH, Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012; 9: 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abramoff MD,, Magalhaes PJ,, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004; 11: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiskur BJ,, Hunt JJ,, Callegan MC. Hypermucoviscosity as a virulence factor in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008. ; 49: 4931–4938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hunt JJ,, Wang JT,, Callegan MC. Contribution of mucoviscosity associated gene A (magA) to virulence in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011. ; 52: 6860–6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mazmanian SK,, Liu G,, Ton-That H,, Schneewind O. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science. 1999; 285: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Navarre WW,, Schneewind O. Proteolytic cleavage and cell wall anchoring at the LPXTG motif of surface proteins in gram positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1994. ; 14: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Greene C,, McDevitt D,, François P,, Vaudaux P,, Lew D,, Foster T. Adhesion properties of mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in fibronectin binding proteins and studies on the expression of the fnb genes. Mol Microbiol. 1995; 17: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McDevitt D,, François P,, Vaudaux P,, Foster T. Molecular characterization of the fibrinogen receptor (clumping factor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1994; 11: 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patti J,, Jonsson H,, Guss B,, et al. Molecular characterization and expression of a gene encoding a Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1992; 267: 4766–4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jett BD,, Gilmore MS. Host-parasite interactions in Staphylococcus aureus keratitis. DNA Cell Biol. 2002. ; 21: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jett BD,, Gilmore MS. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by human corneal epithelial cells: role of bacterial fibronectin-binding protein and host cell factors. Infect Immun. 2002; 70: 4697–4700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rhem MN,, Lech EM,, Patti JM,, et al. The collagen-binding adhesin is a virulence factor in Staphylococcus aureus keratitis. Infect Immun. 2000. ; 68: 3776–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mattsson E,, Heying R,, van de Gevel JS,, Hartung T,, Beekhuizen H. Staphylococcal peptidoglycan initiates an inflammatory response and procoagulant activity in human vascular endothelial cells: a comparison with highly purified lipoteichoic acid and TSST-1. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008. ; 52: 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Heying R,, van de Gevel J,, Que YA,, Piroth L,, Moreillon P,, Beekhuizen H. Contribution of (sub)domains of Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding protein to the proinflammatory and procoagulant response of human vascular endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 2009. ; 101: 495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kerdudou S,, Laschke MW,, Sinha B,, Preissner KT,, Menger MD,, Herrmann M. Fibronectin binding proteins contribute to the adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to intact endothelium in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 2006. ; 96: 183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Edwards AM,, Bowden MG,, Brown EL,, Laabei M,, Massey RC. Staphylococcus aureus extracellular adherence protein triggers TNFα release promoting attachment to endothelial cells via protein A. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e43046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang JE,, Jørgensen PF,, Almlöf M,, et al. Peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus induce tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-10 production in both T cells and monocytes in a human whole blood model. Infect Immun. 2000. ; 68: 3965–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luna JD,, Chan CC,, Derevjanik NL,, et al. Blood-retinal barrier (BRB) breakdown in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis: comparison with vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1beta-mediated breakdown. J Neurosci Res. 1997. ; 49: 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Herbert S,, Ziebandt AK,, Ohlsen K,, et al. Repair of global regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and comparative analysis with other clinical isolates. Infect Immun. 2010. ; 78: 2877–2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Plata K,, Rosato A,, Wegrzyn G. Staphylococcus aureus as an infectious agent: overview of biochemistry and molecular genetics of its pathogenicity. Acta Biochim Pol. 2009. ; 56: 597–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wirtz C,, Witte W,, Wolz C,, Goerke C. Transcription of the phage-encoded Panton-Valentine leukocidin of Staphylococcus aureus is dependent on the phage life-cycle and on the host background. Microbiology. 2009. ; 155: 3491–3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Otto M. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010; 64: 143–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Löffler B,, Hussain M,, Grundmeier M,, et al. Staphylococcus aureus panton-valentine leukocidin is a very potent cytotoxic factor for human neutrophils. PLoS Pathog. 2010; 6: e1000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ibberson CB,, Jones CL,, Singh S,, et al. Staphylococcus aureus hyaluronidase is a CodY-regulated virulence factor. Infect Immun. 2014. ; 82: 4253–4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Luong T,, Lee C. Overproduction of type 8 capsular polysaccharide augments Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Infect Immun. 2002; 70: 3389–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thakker M,, Park J,, Carey V,, Lee J. Staphylococcus aureus serotype 5 capsular polysaccharide is antiphagocytic and enhances bacterial virulence in a murine bacteremia model. Infect Immun. 1998; 66: 5183–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roghmann M,, Taylor K,, Gupte A,, et al. Epidemiology of capsular and surface polysaccharide in Staphylococcus aureus infections complicated by bacteraemia. J Hosp Infect. 2005. ; 59: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fox KF,, Stewart GC,, Fox A. Synthesis of microcapsule by Staphylococcus aureus is not responsive to environmental phosphate concentrations. Infect Immun. 1998. ; 66: 4004–4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]