Abstract

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) family of tumor suppressors, TSC1 and TSC2, function together in an evolutionarily conserved protein complex that is a point of convergence for major cell signaling pathways that regulate mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Mutation or aberrant inhibition of the TSC complex is common in various human tumor syndromes and cancers. The discovery of novel therapeutic strategies to selectively target cells with functional loss of this complex is therefore of clinical relevance to patients with nonmalignant TSC and those with sporadic cancers. We developed a CRISPR-based method to generate homogeneous mutant Drosophila cell lines. By combining TSC1 or TSC2 mutant cell lines with RNAi screens against all kinases and phosphatases, we identified synthetic interactions with TSC1 and TSC2. Individual knockdown of three candidate genes (mRNA-cap, Pitslre, and CycT; orthologs of RNGTT, CDK11, and CCNT1 in humans) reduced the population growth rate of Drosophila cells lacking either TSC1 or TSC2 but not that of wild-type cells. Moreover, individual knockdown of these three genes had similar growth-inhibiting effects in mammalian TSC2-deficient cell lines, including human tumor-derived cells, illustrating the power of this cross-species screening strategy to identify potential drug targets.

INTRODUCTION

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) protein complex is a point of convergence of multiple upstream signaling pathways that is vital for the control of growth and proliferation in response to extracellular signals. Genetic disruption of the TSC protein complex, through mutations in TSC1 or TSC2, gives rise to the TSC and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) diseases, which are systemic disorders associated with the development of widespread neoplastic lesions (1). Current therapeutic strategies targeting the TSC complex and the surrounding network include the target of rapamycin (TOR) inhibitor rapamycin and its derivatives. However, such treatments are limited to cytostatic effects, and tumors rapidly regrow after cessation of treatment (2–4), underscoring the need to identify new therapeutic targets for the treatment of TSC. A common limitation of chemotherapeutic agents is toxicity to healthy tissues, limiting the dose and duration of treatment and thereby restricting their efficacy. Therefore, we sought to identify potential drug targets with synthetic effects in combination with TSC complex components, in which knockdown of the target gene alone has little effect on normal cells but is toxic to TSC-deficient cells.

RNA interference (RNAi) screens in mammalian cells have been extensively used to identify novel drug targets for various tumor types, and results from these studies have led to the identification of a number of candidates. However, many candidates identified from such screens have suffered from reproducibility issues, and as such, few functional therapeutic targets have emerged (5). One way to address this issue is to perform cross-species screens because candidates with conserved effects between organisms are more likely to be functional therapeutic targets in follow-up studies (6). Because the TSC signaling network is conserved between Drosophila and mammals and robust methods for Drosophila cell-based screens have been established (6), we decided to perform combinatorial screens in Drosophila cells to identify synthetic interactions with TSC1 and TSC2 (also known as Gigas) and evaluate whether the identified candidates had conserved synthetic effects in mammals.

As demonstrated in yeast studies, combinatorial screening is an effective way to identify synthetic interactions (7, 8). However, when multiple RNAi reagents are used in combination, the consequences of off-target effects and variable knockdown efficiencies are compounded, leading to high false-positive and false-negative rates (9, 10). Deconvolving biologically meaningful candidates from such screens requires extensive secondary screening and validation, making this approach time-consuming and expensive.

Here, we first describe a method for the generation of isogenic mutant Drosophila cell lines, which we then used for synthetic screens in Drosophila cells that combined CRISPR-generated cell lines deficient in TSC1 or TSC2 with RNAi screening methods. By combining these two technologies and screening in two independent TSC mutant backgrounds, we identified three robust candidate drug targets without needing to perform secondary screening. We demonstrated that all three of these candidates have conserved synthetic interactions with TSC2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and human tumor-derived cell lines, illustrating the power of this approach to identify potential candidates for therapeutic targeting.

RESULTS

Optimization of the CRISPR system for Drosophila cell culture

CRISPR functions with high efficiency in many organisms, including Drosophila (11–19), making it an ideal system for generating mutant cell lines for combinatorial screening. However, our ability to predict off-targets and short guide RNA (sgRNA) efficacy before testing is currently limited, and it is unclear whether design rules from mammalian systems are transferable to Drosophila cells (20–23). We therefore decided to assess the specificity of CRISPR in Drosophila cell culture. We first generated a vector encoding both Cas9 and sgRNA (Supplementary file 1) and then used this to express 75 variants of an sgRNA in S2R+ cells with different mismatches to a single target sequence present in a luciferase-based reporter (Supplementary file 2) or in the genome. The extent and position of mismatch required to prevent mutation was assessed by measuring changes in luciferase expression from the reporter construct (Fig. 1A) or using high-resolution melt assays (HRMAs) on endogenous sequences (fig. S1). Both approaches produced similar results that are consistent with previous observations (13, 24). For example, in previous reports from mammalian systems (21), mismatches at the 5′ end of the sgRNA sequences were better tolerated than those at the 3′ end. However, in some cases, a single mismatch was sufficient to prevent detectable mutation. In addition, we found that three mismatches were sufficient to prevent detectable mutations except when all mismatcheswere at the 5′ end of the sgRNA, consistent with a previous report investigating the specificity of CRISPR in vivo in Drosophila (25). We therefore used 3 base pairs (bp) of mismatch as a cutoff to annotate predicted off-targets for all possible sgRNAs in the Drosophila genome and included these data in an updated version of our previously reported sgRNA design tool (www.flyrnai.org/crispr2) (fig. S2) (16). Note that to be included in this tool, sgRNAs must have a unique 3′ seed sequence. As such, no annotated sgRNA can have off-targets with mismatches clustered at the 5′ end. Using these updated off-target predictions, we estimate that 97% of genes in the Drosophila genome can be targeted with specific sgRNAs, making this an ideal system for the generation of knockout cell lines.

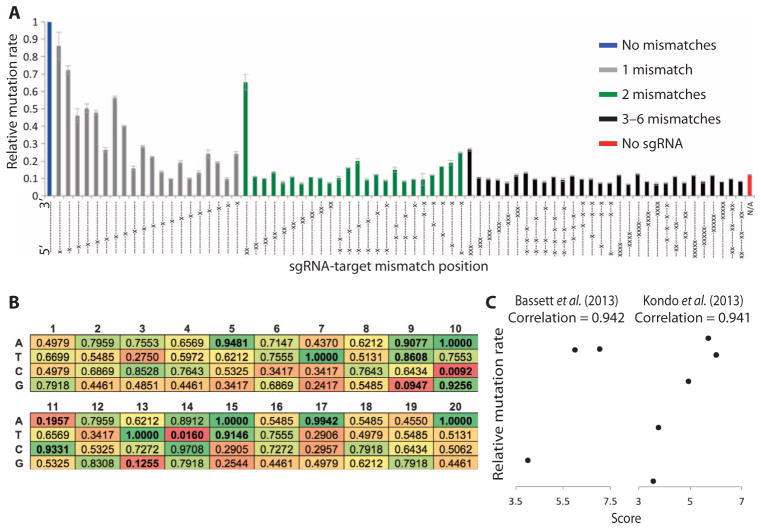

Fig. 1. Optimization of the CRISPR system for Drosophila cell culture.

(A) Graph showing relative mutation rates from 75 sgRNAs used to target a single sequence cloned into a luciferase reporter. Mutation rate is calculated as 1/firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity to control for differential transfection efficiency. Bars show mean relative mutation rates from three biological replicates using sgRNAs with 0 mismatches (blue bar), 1 mismatch (gray bars), 2 mismatches (green bars), or ≥ 3 mismatches (black bars) or in the absence of sgRNA (red bar). Dashes indicate nucleotides that are matched between sgRNA and the target sequence. Crosses indicate the position of mismatches. (B) Matrix showing the enrichment P values of each nucleotide in each position among high-efficiency sgRNAs. (C) Validation of efficiency scores generated using the matrix in (B) by correlating score (horizontal axis) with efficiency (vertical axis) from two independent publications (see fig. S3D for comparison with an additional data set).

Because the rate of mutations varies widely between different sgRNAs (26–28), we tested whether efficiency could be predicted on the basis of the sgRNA sequence. We generated 75 additional sgRNAs each targeting luciferase-based reporter constructs with no mismatches and tested mutation efficiency for each (table S1). Using this panel of sgRNAs and associated efficiencies, we first considered whether GC content correlated with mutation rate as has been suggested in several previous reports (25, 27, 29, 30). In contrast with the results of Ren et al. (25) suggesting that greater than 50% GC content in the six PAM (protospacer-adjacent motif)–proximal nucleotides is associated with high efficiency, we found no such correlation for any part of the sgRNA sequence (fig. S3, A to C). However, our observations are consistent with a mammalian study suggesting that both high and low GC content at the 3′ end are associated with low efficiency [fig. S3B and (27)]. Next, we tested whether a more general sequence-based approach could improve efficiency prediction. We analyzed the nucleotide content of all 75 sgRNAs considering each position separately and generated a probability matrix linking nucleotide content with mutation rate (Fig. 1B), which was used to predict efficiency scores based on sgRNA sequence. To test the performance of this approach, we generated scores for sgRNAs used in three previous Drosophila publications and found a strong correlation with reported efficiencies for two of them (Fig. 1C). Note that sgRNAs unlikely to produce a mutant phenotype (targeting close to the 3′ end of genes) or with apparent viability effects (few emerging adults) were not included in this analysis. However, very little correlation was detected for a third data set (fig. S3D). In addition, the criteria that we identified for high sgRNA efficiency differ from those of two studies performed in mammalian systems (26, 27), and these two studies also differ from the GC requirements identified previously in Drosophila (25), suggesting that in some cases, efficiency criteria may depend on factors other than simply sgRNA sequence. Finally, we generated predicted scores for all sgRNA target sites in the Drosophila genome on the basis of our findings and annotated these in our online design tool (www.flyrnai.org/crispr2) (fig. S2). With this updated tool, sgRNAs can be quickly designed for various applications.

Generation of stable mutant cell lines

The CRISPR system works efficiently in Drosophila cell culture (11, 12). However, it has not yet been possible to generate cell lines in which all cells are null mutants for the target gene, because previous studies have shown that mutant populations quickly revert back to wild type. To solve this issue, we first generated optimized sgRNAs to maximize their efficiencies while avoiding off-target effects (Fig. 1 and fig. S2). In addition, we implemented a method to predict the frameshift and in-frame mutation rates for each sgRNA target site (31) and annotated each of these mutation rates in our online design tool (www.flyrnai.org/crispr2). Second, to ensure that mutant cell lines do not revert to wild type, a method is required to grow cultures from individual cells, a historically difficult problem with Drosophila cells. Various methods for this problem have been proposed (32–34), but none have been widely used because of either difficulty in identifying single cell–derived cultures or very low efficiencies. To substitute for paracrine factors that promote the survival of individual Drosophila cells cultured in populations, we tested whether the use of culture media preconditioned with wild-type S2R+ cells would allow the efficient growth of individual S2R+ cells isolated by flow cytometry. When seeded into regular media, 0 of 190 individual cells formed colonies, but when seeded into conditioned media, 30 of 190 (16%) cells formed colonies that could be expanded into clonal cultures (Fig. 2A). Varying the fetal bovine serum (FBS) concentration had no additional effect.

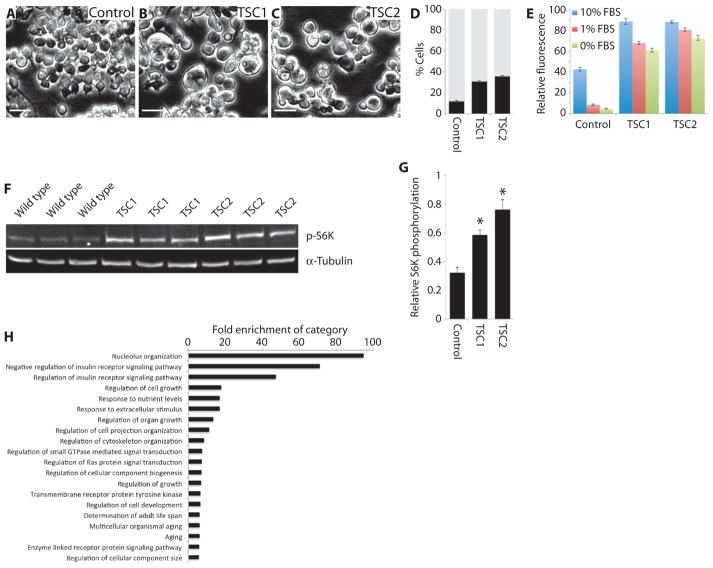

Fig. 2. Generation of mutant cell lines.

(A) Survival rates of single S2R+ cells seeded into different medium formulations. “Clones” represents the number of seeded samples that produced viable populations of cells 3 weeks after seeding. Schneider’s medium was supplemented with FBS at the indicated concentrations and was preconditioned using S2R+ cells where indicated. (B) HRMA results for single S2R+ cells from a population 4 days after treatment with CRISPR targeting the yellow gene. The graph shows the difference in fluorescence between each sample and a mean control curve against temperature (scale from 76° to 84°C). (C) Graph showing relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity for either wild-type (black bars) or STAT92E (gray bars) mutant cells in the presence or absence of JAK/STAT pathway activation (upd ligand overexpression) and with or without activation in the presence of two different dsRNAs targeting STAT92E (RNAi-1 and RNAi-2). Bars show the mean from five biological replicates; error bars represent SEM. All differences between wild-type and STAT92E cells were significant (P < 0.05).

One difficulty associated with the isolation of mutant cells from Drosophila S2R+ cells is that they are aneuploid, containing roughly four copies of any given genomic locus (35). Thus, the chances of identifying cells in which all alleles carry frameshift mutations are considerably lower than for diploid cells. To assess the ability of CRISPR to produce homozygous mutations in these cells, we targeted the yellow gene and tested 30 individual cells for the presence of mutations using high-resolution melt (HRM) assays. Twenty-one (70%) carried mutations at the target locus (Fig. 2B). The eight samples with the strongest signal in the HRM assays were analyzed by sequencing. No wild-type sequences were detected for any of these samples, and seven of eight contained a single mutation in all derived sequences (fig. S4). The identification of homozygous mutations in seven of eight cells tested is consistent with previous reports of high rates of gene conversion after genome editing (36–38); however, it is also possible that homozygous mutations are generated as a result of chromosome loss. Therefore, the HRM assay is an effective method to identify fully mutant clones.

Next, to test the efficacy of our sgRNA design tool and the combined CRISPR and single-cell cloning approach (fig. S5A), we targeted a gene for which loss of protein function could easily be assayed: STAT92E, which encodes a STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) transcription factor that is activated by JAK (Janus kinase) (fig. S5B). Fifteen clones were analyzed, of which 13 carried mutations on all alleles. Further testing showed that the expected phenotype was produced from these knockouts, with the STAT92E line unable to respond to JAK/STAT pathway stimulation induced by upd ligand overexpression (Fig. 2C). In addition, the effect of the STAT92E mutation was considerably stronger than that produced by targeting STAT92E with double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which reduced the response to JAK/STAT pathway stimulation but did not prevent it. These results demonstrate that our approach provides an efficient CRISPR-based method for the production of stable, homogeneous mutant Drosophila cell lines.

Synthetic screens using TSC1 and TSC2 mutant lines

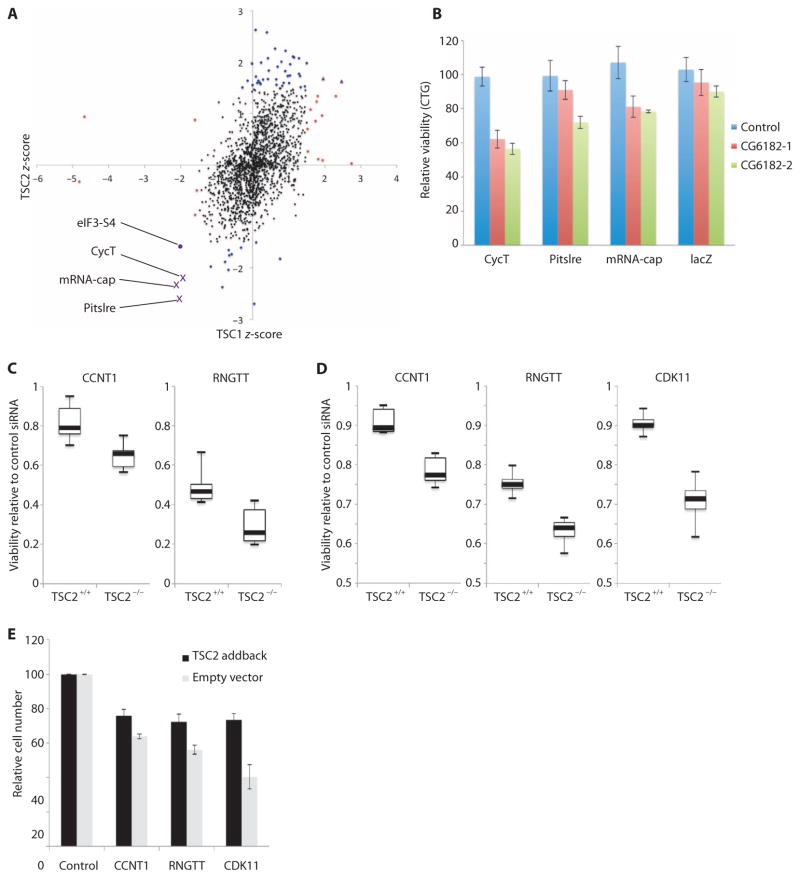

We generated cell lines carrying frameshift mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes using the approach described above (fig. S6). To characterize the lines, we tested whether they showed phenotypes similar to those previously reported in vivo or in mammalian cell lines (39–43) because antibodies against Drosophila TSC1 or TSC2 are not available. Three phenotypes were considered: cell size, responsiveness to growth factor deprivation, and phosphorylation of the downstream TOR target S6 kinase (S6K). TSC1 and TSC2 cell lines had all three phenotypes: an increased cell diameter (Fig. 3, A to D), an inability to modify population growth in the absence of growth factors (Fig. 3E), and increased phosphorylation of S6K (when normalized to α-tubulin; Fig. 3, F and G). To further characterize the mutant cell lines, we performed phosphoproteomic analysis. One hundred twenty-eight phosphosites showed a more than 1.5-fold increase or decrease in both mutant lines compared to wild-type cells (table S2). Gene ontology (GO) analysis demonstrated that 20 of the top 30 most significantly enriched categories were consistent with known functions of the TSC network (Fig. 3H and table S3), including insulin signaling, response to nutrients, and the growth of cells and tissues. Together, these results suggest that the cell lines accurately represent TSC mutant models.

Fig. 3. Characterization of TSC mutant cell lines.

(A to C) Images of representative fields from wild-type (A), TSC1 mutant (B), or TSC2 mutant (C) cell lines. All images were taken at the same magnification and using the same settings. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Graph showing frequency of cell sizes for the cell lines indicated, divided into “low diameter” (gray bars) or “high diameter” (black bars) using a cutoff at which most wild-type cells fall into the low-diameter category. Bars represent the mean from three biological replicates; error bars indicate SEM. (E) Graph showing the relative rates of population growth for the indicated cell lines in either complete medium (10% FBS; blue bars), under partial serum starvation conditions (1% FBS; red bars), or under complete serum starvation conditions (0% FBS; green bars). Note that these values represent a combination of cell growth and proliferation. Bars show the mean of 24 samples per cell line and condition; error bars represent SEM. (F) Images of Western blots stained for phosphorylated S6K (p-S6K) or α-tubulin as indicated. Samples represent biological triplicates from S2R+, TSC1, and TSC2 cells. p-S6K amounts were normalized to α-tubulin because an antibody for Drosophila total S6K was not available. (G) Quantification of p-S6K for the indicated cell lines as shown in the Western blots in (F). Bars represent mean change in p-S6K normalized to α-tubulin for three biological replicates in each case. Error bars represent SEM; asterisks indicate significant differences from control (P =0.01), determined by t tests. (H) Graph indicating the fold enrichment of the indicated GO categories in phosphoproteomic data from TSC1 and TSC2 mutant cells compared to wild type. All samples are enriched with P values <0.05.

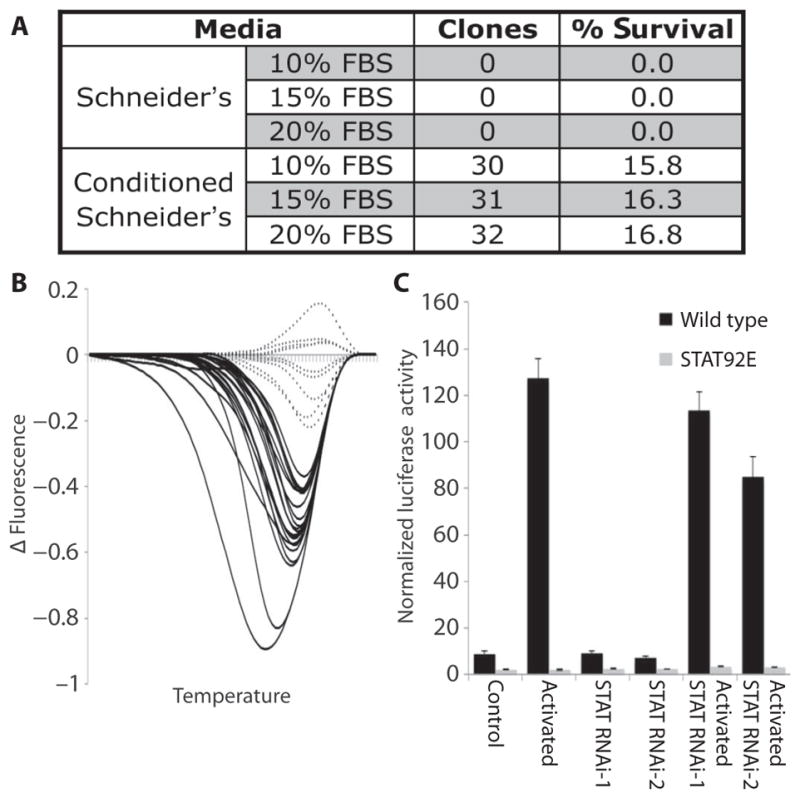

Next, to take advantage of the homogeneous TSC1 and TSC2 mutant cell lines, we performed a combinatorial RNAi screen of all Drosophila kinases (376) and phosphatases (159). We measured population viability using a total adenosine triphosphate (ATP) readout to capture changes in cell growth, proliferation, and cell death (referred to as “population growth” from here on). Any samples with significant effects on the population growth of wild-type cells were discarded to identify TSC-specific hits. Twenty of the remaining knockdowns had significant effects on TSC1 mutant cells, and 49 hits significantly affected TSC2 mutant cells (Fig. 4A and table S4). Because TSC1 and TSC2 act as part of a protein complex and mutations in either gene give rise to the TSC disease, we decided to consider for further studies genes that were identified in both the TSC1 and TSC2 screens. This approach filtered out the noise associated with either individual screen and identified genes with the most robust synthetic interactions with the TSC complex. The knockdown of three genes (mRNA-cap, Pitslre, and CycT) showed robust and specific effects on TSC1- and TSC2-deficient cells (Fig. 4A, purple crosses).

Fig. 4. Identification of TSC-specific drug targets using synthetic screening.

(A) Scatter plot showing the results of screens in Drosophila TSC1 and TSC2 mutant cell lines. dsRNAs that showed changes (see Materials and Methods) in wild-type cells are not shown in the graph. Points indicate the z-scores from three replicate screens in TSC1 cells (horizontal axis) and TSC2 cells (vertical axis). Dots represent candidates with no significant effect (black circles), TSC1-specific candidates (red circles), TSC2-specific candidates (blue circles), and candidates from TSC1 and TSC2 cells (purple crosses). The three genes showing synthetic reductions in population growth with both TSC1 and TSC2 are labeled. In addition, results for eIF3-S4 are plotted on the same graph for comparison (purple circle). (B) Graph showing relative viability (measured using CellTiter-Glo) for S2R+ cells treated with control (lacZ) dsRNA (blue bars) or two different dsRNAs targeting CG6182 (red and green bars) in combination with dsRNAs targeting CycT, Pitslre, mRNA-cap, or lacZ. Bars represent mean values from three biological replicates normalized to controldsRNAtreatments;error bars indicate SEM.(C) Summary plots showing onetimepoint from population growthassays in TSC2-deficient or wild-type MEFs treated with the indicated siRNAs (see fig. S7 for full time courses). Boxplots represent median (thick black lines), interquartile range (boxes), and min/max (error bars) from two biological replicates for the indicated genes in TSC2-deficient or wild-type background. The vertical axis represents change in ATP concentrations after 48 hours of culture relative to cells treated with control siRNA, measured using CellTiter-Glo assays. (D) Summary plots showing one time point from population growth assays in TSC2-deficient AML cells. Boxplots are as described in (C) and represent three biological replicates (see fig. S7 for full time courses). All differences between TSC-deficient and wild-type cells are significant (P < 0.05). (E) Graph showing the relative cell numbers after siRNA-mediated knockdown of the indicated genes in AML cells with (black bars) or without (gray bars) TSC2 addback. Bars represent the average of at least four biological replicates; error bars indicate SEM. Differences between TSC2 addback and empty vector conditions were significant for all three genes tested (P < 0.05).

The first candidate, mRNA-cap, is the 5′ triphosphatase and guanylyl-transferase that catalyzes the first two steps required for the formation of a 5′ 7-methylguanylate mRNA cap, which is necessary for the initiation of cap-dependent translation (44). Because activation of mammalian TOR (mTOR) promotes cap-dependent translation initiation through multiple downstream targets (45, 46), our findings suggest that TSC mutant cells depended on mRNA capping, an event that precedes the steps in translation regulated by mTOR. Our phosphoproteomic analysis identified phophosites on distinct components of the translation initiation machinery, such as Thor, eIF4G, eIF3-S10, and eIF2B, being either increased or decreased in either TSC1, TSC2, or both mutant cell lines compared to control. In addition, phosphorylation changes were detected in both cell lines for two other proteins that directly interact with core components of the translation initiation complex (Ens and Map205, table S2) (47, 48).

Given the link between TSC signaling and translation initiation, we tested whether another translation initiation component showed a similar synthetic relationship with the TSC mutant cell lines. We knocked down eIF3-S4 in wild-type and TSC1 or TSC2 mutant cells using the same assays as for the kinase and phosphatase screen. Both TSC1 and TSC2 mutant cells had a synthetic decrease in population growth (Fig. 4A, purple circle), suggesting that the control of cap-dependent translation initiation may be a promising therapeutic target for TSC-dependent and/or mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) hyperactive disease.

The second candidate, CycT, is a kinase implicated in the regulation of transcriptional elongation (49, 50). mRNA-cap is recruited to the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) C-terminal domain phosphorylated at Ser5 to form the 5′ mRNA cap, and CycT promotes RNA Pol II phosphorylation at this site. Thus, the function of CycT may be related to that of mRNA-cap. Finally, the third candidate, Pitslre, is a cyclin-dependent kinase that has been implicated in the regulation of autophagy (51). Disruption of the TSC complex leads to reduced autophagy, which has been exploited as a potential therapeutic strategy by combining autophagy inhibitors such as chloroquine with mTOR inhibitors (52).

To determine whether the identified interactions extended to CG6182 (TBC1D7 in mammals), a third component of the TSC complex (53), we tested whether combinatorial knockdown of mRNA-cap, CycT, or Pitslre with CG6182 knockdown produced greater reduction in population growth than either knockdown alone. In all three cases, the combination of dsRNAs targeting the candidate gene and CG6182 produced a synthetic reduction in population growth (Fig. 4B).

Conservation of synthetic interactions in mammalian cells

Because all three candidates from the Drosophila screens have orthologs in mammals (table S5), we tested whether the synthetic interactions of mRNA-cap, Pitslre, and CycTwith TSC1 and TSC2 were conserved. We used small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting the orthologs of each of the three genes in TSC2-deficient MEFs compared to littermate-derived wild-type MEFs. Both RNGTT (mRNA-cap in Drosophila) and CCNT1 (CycTin Drosophila) knockdowns caused reduced population growth in TSC2−/− cells compared to wild type, although no synthetic effect was detected with CDK11 (Pitslre in Drosophila) because CDK11 knockdown reduced mTORC1 activity in both wild-type and TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 4C and figs. S7, A to F, and S8). We noted, however, that similar synthetic interactions were not detected when any of the three candidates were knocked down in combination with TSC1, TSC2, or TBC1D7 using combinatorial siRNA treatments (fig. S9). These results suggest that although the target proteins were efficiently reduced (fig. S8), either residual protein was sufficient to restore some function or long-term effects of loss of function of the TSC complex were required. In the latter case, although TSC proteins were depleted, the effect might not be detectable because the cells might still have enough of the components normally regulated by TSC. Further, to assess the relevance of these potential drug targets to human tumor cells, we used siRNA to knock down the three hits in a TSC2-deficient human renal angiomyolipoma (AML) cell line derived from a patient with LAM (54). For isogenic comparison, the candidate genes were knocked down using siRNA in the same cell line stably reconstituted with wild-type TSC2. To assess the effectiveness of the TSC2 addback, we measured S6K phosphorylation and cell size with and without TSC2 reconstitution. As expected, TSC2 addback reduced mTORC1 activity and cell size (fig. S10). siRNAs targeting each of the three candidate genes significantly reduced the population growth of TSC2 null cells as assessed by using total ATP as a readout (Fig. 4D and fig. S7, G to I). In addition, synthetic effects were seen on cell numbers for all three genes (Fig. 4E). In contrast, two negative control genes that did not score in the Drosophila screen [Src42A (FRK in mammals) and for (PRKG1 in mammals)] showed no synthetic effects (fig. S7, J and K), indicating that the three gene products we have identified could be promising drug targets for TSC and LAM.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a synthetic screening method that combines the CRISPR genome-editing system with well-established RNAi methodologies. Previous combinatorial screens in Drosophila cells have been performed by treating cells with multiple RNAi reagents simultaneously (9, 10). However, whereas this approach has been used successfully, limitations of RNAi including incomplete transfection, partial knockdown, and off-target effects are compounded, leading to high false-negative and false-positive rates. A laborious and time-consuming secondary screening is therefore required to identify the robust hits from these screens.

The screening strategy we have developed offers several advantages compared to combinatorial RNAi treatment. First, by combining CRISPR-generated mutant cell lines with single RNAi reagents, we avoid much of the noise associated with dual RNAi–based screening approaches. The use of homogeneous populations of null mutant cells avoids the issues of incomplete transfection and incomplete knockdown. In addition, once generated, in-depth characterization of the mutant cell lines can be performed to establish whether off-target mutations are present. In the case of our screen, this reduction in noise as well as the comparison between two independent mutant cell lines completely avoided the need for secondary screening.

Second, in some cases, mutant cell lines may represent a considerable improvement in the quality of disease models over RNAi-mediated knockdowns. For example, diseases such as TSC are caused by loss-of-function mutations rather than by partial transient reduction in protein abundance. The establishment of a mutant cell line enables cellular adaptation to the induced mutation, likely generating a more representative cellular environment. This is illustrated by the lack of synthetic effects detected using siRNA-mediated combinatorial knockdowns in MEFs (fig. S9). One implication is that future screens performed in such adapted backgrounds may lead to hits with more reproducible effects in a therapeutic setting.

Third, previous screening strategies have required laborious secondary screening and validation of hits to identify those that are robust. Here, we have simultaneously screened two mutant backgrounds (TSC1 and TSC2). Because both of these proteins act as part of the TSC complex, similar effects are expected from the two knockouts. Therefore, by considering the overlap between these data sets, we were able to quickly identify the most robust candidates. The advantage of this approach is reflected in the fact that the identified synthetic candidates were validated in both mammalian cell types, resulting in a very rapid translation from screening in a model organism to identification of clinically relevant potential drug targets. Finally, by considering conservation between Drosophila and humans, we increase the likelihood of the identified effects being reproducible, an issue that has been a major limitation in previous studies (5).

Current treatments for TSC-related diseases include rapamycin and its derivatives, which function by blocking mTOR activity downstream of the TSC complex. A problem associated with this approach is that the molecular vulnerabilities caused by mutations in the TSC complex are reversed, thereby reducing the opportunities available to kill affected cells (55). The targets we have identified here offer the potential to bypass this issue. Indeed, none of the target genes affected the phosphorylation of S6K in AML cells when knocked down, and two (CCNT1 and RNGTT) had no effect on the phosphorylation of S6K in TSC2-deficient MEFs (fig. S8), suggesting that some molecular vulnerabilities caused by mTOR activation may persist after inhibition of these potential drug targets. For example, inhibition of mRNA-cap would not be expected to have direct effects on autophagy and, therefore, may maintain the energy stress associated with TSC mutations. However, further work will be required to determine whether inhibition of these factors is more efficacious than mTOR inhibition.

Finally, whereas we have used mutant cell lines to develop an improved synthetic screening method, there are many other possible applications of stable homogeneous mutant lines, for example, in modeling of diseases caused by single null mutations or epistasis experiments where residual expression of the target gene can complicate interpretation of results. We therefore expect this method to be widely applicable to many different areas of research.

In conclusion, by combining established RNAi screening methods in Drosophila cells with CRISPR genome-editing technology, we have developed a powerful new approach to synthetic screening. The robustness of this method is demonstrated by the conservation of the identified synthetic interactions in mouse and human systems, suggesting that it will be a generally applicable approach to investigate various biological and disease-relevant questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of CRISPR expression vector

A Drosophila codon-optimized Cas9 with a 3xFlag tag and nuclear localization signal elements at both 5′ and 3′ was synthesized by GenScript, and the Drosophila U6 and act5c promoters were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified from Drosophila genomic DNA (table S6). These were used to replace the human codon-optimized Cas9 and human U6 and CGh promoters, respectively, of the pX330 (13) plasmid to yield the pl018 plasmid (Supplementary file 1). sgRNA homology sequences were cloned into pl018 using pairs of DNA oligonucleotides, which were annealed and ligated into Bbs I sites according to a previously described protocol (table S6) (13).

Luciferase-based mutation reporter assays

The luciferase reporter vector was constructed by PCR amplifying the metallothionein promoter from pMK33 (56) and luciferase gene from pGL3 (table S6) (57) and combining these with annealed oligos containing an sgRNA target site (tables S1 and S6) and a custom-made cloning vector using Golden Gate assembly. Luciferase assays were performed by transfecting S2R+ cells with the relevant pl018 plasmid, luciferase reporter, and pRL-TK (Promega) (to allow normalization of transfection efficiencies between samples) in 96-well plates using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Twenty-four hours after transfection, CuSO4 was added to the cell medium at a final concentration of 140 μM, and cells were incubated for a further 16 hours. Firefly and Renilla luciferase readings were taken using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform (Molecular Devices) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Online tools

An improved version of CRISPR design tool was implemented reusing some of the modules developed previously (16). Besides allowing users to choose different off-target thresholds, this version also displays precalculated efficiency score and restriction enzyme annotation. The efficiency score was calculated on the basis of a probability matrix computed using the in vitro cell line data described in Fig. 1A. It reflects a cumulative P value for high efficiency of each nucleotide from position 1 to 20, with higher values representing higher efficiency. A user interface allowing efficiency score calculation for user-provided sequences was also developed as part of the improved tool, which dynamically calculates predicted efficiency scores for each input sequence from position 1 to 20 or over a user-defined region (fig. S2).

HRMAnalyzer was written as a series of Matlab programs running under the control of CGI front-end implemented in Perl and JavaScript. The Matlab programs are compiled as stand-alone executable programs and called from within the Perl CGI back-end script. Both tools are hosted on a shared server provided by the Research Information Technology Group (RITG) at Harvard Medical School.

Transfections

Cells were transfected using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For generation of mutant cell lines, we used 360 ng of pl018 plasmid and 40 ng of actin–green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmid as a marker of transfected cells. Transfections were performed in six-well plates and, unless stated otherwise, were incubated for 4 days at 25°C before further processing.

Production of conditioned media

S2R+ cells were incubated with fresh Schneider’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 16 hours while in log-phase growth. The medium was then filtered to remove the cells and diluted 50% with fresh medium supplemented with FBS to obtain the required final FBS concentration.

Single-cell cloning

Cloning of single cells was performed using fluorescence-activated cell sorting of GFP-marked cells. Untransfected cells were used to determine background fluorescence amounts before selecting the top 10% of GFP-expressing cells for isolation. Individual cells were sorted into 96-well plates containing culture medium. After 2 or 3 weeks of culture, single-cell clones were identified visually and isolated into larger cultures.

HRM assays

PCR fragments were prepared from genomic DNA as described for sequencing analysis. Reaction products were then diluted 1:10,000 before an additional round of PCR amplification using Precision Melt Supermix (Bio-Rad) and nested primers to generate a product <120 bp in length (95°C 3 min; 50 rounds of 95°C 30 s, 60°C 18 s, plate read; 95°C 30 s; 25°C 30 s; 10°C 30 s; 55°C 31 s; ramp from 55° to 95°C and plate read every 0.1°C). Data were analyzed using HRMAnalyzer, available at www.flyrnai.org/HRMA. See table S6 for primer sequences.

Sequence verification of clones

Genomic DNA was prepared from cultured cells by resuspension in 100 μl of lysis buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl, and proteinase K (200 μg/ml)] and incubation in a thermocycler for 1 hour at 50°C followed by denaturation at 98°C for 10 min. Target sequences were cloned by PCR using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and supplemented with an additional 2.5 mM MgCl2 (35 cycles: 96°C, 30s; 50°C, 30s; 72°C, 30s). PCR products were gel-purified, cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and transformed into Top10 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen). After transformation, single colonies were isolated for sequencing. To assess homozygosity of single-cell samples, a minimum of five colonies were sequenced per sample. For identification of mutant cell lines, a minimum of 20 colonies were analyzed.

Analysis of STAT92E activity

S2R+ and STAT92E cell lines were transfected using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to introduce upd complementary DNA cloned into pMK33 expression vector, Renilla expression vector (pRL-TK, Promega), and 10X-STAT-luc (58) into experimental samples or pMK33, pRL-TK, and 10X-STAT-luc into control samples. RNAi samples included an additional 50 ng of dsRNA (DRSC ID: DRSC16870 or DRSC37655) from the dsRNA template collection at the Drosophila RNAi Screening Center (DRSC) (www.flyrnai.org). Cells were transfected for 24 hours before the addition of CuSO4 at a final concentration of 140 μM and incubation for a further 16 hours. Firefly and Renilla luciferase measurements were performed using a SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform (Molecular Devices).

Cell size assays

S2R+, TSC1, and TSC2 mutant cell lines were analyzed using a BD Biosciences LSR Fortessa X-20 cell analyzer to measure forward scatter for each cell as a proxy for cell diameter.

Cell line growth assays

Five thousand cells from each line were seeded into 384-well plates containing 50 μl of culture medium and incubated at 25°C for 5 days. CellTiter-Glo reagent (27 μl; Promega) was added to each well before reading luminescence using a SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform (Molecular Devices).

Quantitative phosphoproteomics

Phosphoproteomic analysis was performed as described previously (59). Briefly, S2R+, TSC1, or TSC2 mutant cells were serum-starved for 16 hours before lysis in 8 M urea. Samples were then digested with trypsin, and peptides were chemically labeled with TMT Isobaric Mass Tags (Thermo Scientific),separated into 12 fractions by strong cation exchange chromatography, purified with TiO2 microspheres, and analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry on an Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were identified by Sequest and filtered to a 1% peptide false discovery rate (FDR). Proteins were filtered to achieve a 2% final protein FDR (final peptide FDR near 0.15%). TMT reporter ion intensities for individual phosphopeptides were normalized to the summed reporter ion intensity for each TMT label. The localizations of phosphosites were assigned using the Ascore algorithm.

Synthetic screening

S2R+, TSC1, and TSC2 mutant cell lines were each screened in triplicate using the “kinases and phosphatases” sublibrary provided by the DRSC (www.flyrnai.org). Screening was performed following standard procedures as described by the DRSC (www.flyrnai.org/DRSC-PRR.html). Briefly, for each 384-well plate, 5000 cells in 10 μl of FBS-free medium were seeded into each well, already containing 5 μl of dsRNA at a concentration of 50 ng/μl. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 45 min before adding 35 μl of 14% FBS medium (bringing the final FBS concentration to 10%). The plates were incubated at 25°C for 5 days before assaying ATP concentrations using CellTiter-Glo assays (Promega) and a SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform (Molecular Devices). The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay determines the number of viable cells in culture on the basis of quantitation of the ATP present, thus measuring changes in cell growth, proliferation, and/or cell death (population growth).

CellTiter-Glo data were analyzed by normalizing the data to the median value of each column (to correct for pipetting errors) and calculating the z-scores for each trial individually. Z-scores greater than 1.5 or less than −1.5 in at least two of three trials were considered to affect population growth significantly. Synthetic hits were identified as dsRNAs that significantly affect the population growth of TSC1 or TSC2 mutant cell lines but not S2R+.

Validation of synthetic interactions in mammalian cells

TSC2+/+;TP53−/− and TSC2−/−;TP53−/− MEFs (60) and TSC2-deficient AML cells with empty vector or TSC2 addback (61) were transfected with siGENOME SMARTpool siRNAs (Dharmacon) targeting CCNT1, RNGTT, or CDK11, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s reverse transfection protocol. ATP concentrations were quantified using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and used for Western blot analysis: TSC2 (#3612), phospho-Thr389 S6K (#9234), S6K (#2708), GAPDH (#5174), CCNT1 (#8744), and CDK11 (#5524). RNGTTantibody was purchased from Novus Biologicals (#NBP1-49972).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Sabatini for useful discussion on cell cloning, D. Doupé for useful discussion on homologous recombination, I. Flockhart for help with the development of HRMA data analysis tools, and E. Henske for the AML-derived cell line.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH (5R01DK088718, 5P01CA120964, and R01GM067761) and the Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0179). S.E.M. also receives support from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, which is supported in part by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant #NIH 5 P30 CA06516. N.P. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. R.S. is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Author contributions: B.E.H., S.E.M., B.D.M., and N.P. designed experiments; B.E.H., A.J.V., C.K., R.S., S.L., M.B., and R.T. performed experiments; B.E.H., Y.H., B.Y., and C.R. developed the online CRISPR design tools; B.E.H., R.S., and Y.H. analyzed experimental results; B.E.H. and N.P. wrote the paper.

Competing interests: B.E.H., A.J.V., B.D.M., and N.P. have filed a provisional patent regarding the targeting of CCNT1, RNGTT, and CDK11 in tuberous sclerosis complex. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The mass spectrometry phosphoproteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (62) through the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD002670.

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/8/393/rs9/DC1

Fig. S1. Analysis of CRISPR specificity using quantitative HRM.

Fig. S2. An improved sgRNA design tool.

Fig. S3. Analysis of GC content in relation to sgRNA efficiency.

Fig. S4. Sequencing of individual CRISPR mutant cells.

Fig. S5. Generation of isogenic mutant cell lines.

Fig. S6. Generation of TSC1 and TSC2 mutant cell lines.

Fig. S7. Synthetic effects in MEFs and AML cells.

Fig. S8. Analysis of knockdown of candidate genes on mTOR signaling.

Fig. S9. Synthetic effects of candidate genes with TBC1D7.

Fig. S10. Analysis of TSC2 addback efficacy in AML cells.

Table S1. sgRNA efficiency in relation to GC content data.

Table S2. Phosphorylation changes common to TSC1 and TSC2 cell lines.

Table S3. GO analysis of phosphoproteomic data.

Table S4. Synthetic screen results.

Table S5. Conservation of synthetic screen candidate genes. Table S6. Primers used in this study.

Supplementary file 1. GenBank sequence of CRISPR cell line expression vector (pl018).

Supplementary file 2. GenBank sequence of the luciferase mutation reporter vector.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, Schmithorst VJ, Laor T, Brody AS, Bean J, Salisbury S, Franz DN. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormack FX, Inoue Y, Moss J, Singer LG, Strange C, Nakata K, Barker AF, Chapman JT, Brantly ML, Stocks JM, Brown KK, Lynch JP, III, Goldberg HJ, Young LR, Kinder BW, Downey GP, Sullivan EJ, Colby TV, McKay RT, Cohen MM, Korbee L, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Lee H-S, Krischer JP, Trapnell BC National Institutes of Health Rare Lung Diseases Consortium; MILES Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1595–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, Agricola K, Tudor C, Mangeshkar P, Wilson KA, Byars A, Sahmoud T, Franz DN. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaelin WG., Jr Molecular biology. Use and abuse of RNAi to study mammalian gene function. Science. 2012;337:421–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1225787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohr SE, Smith JA, Shamu CE, Neumüller RA, Perrimon N. RNAi screening comes of age: Improved techniques and complementary approaches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong AH, Evangelista M, Parsons AB, Xu H, Bader GD, Page N, Robinson M, Raghibizadeh S, Hogue CW, Bussey H, Andrews B, Tyers M, Boone C. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science. 2001;294:2364–2368. doi: 10.1126/science.1065810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong AH, Boone C. Synthetic genetic array analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;313:171–192. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn T, Sandmann T, Fischer B, Axelsson E, Huber W, Boutros M. Mapping of signaling networks through synthetic genetic interaction analysis by RNAi. Nat Methods. 2011;8:341–346. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nir O, Bakal C, Perrimon N, Berger B. Inference of RhoGAP/GTPase regulation using single-cell morphological data from a combinatorial RNAi screen. Genome Res. 2010;20:372–380. doi: 10.1101/gr.100248.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassett AR, Tibbit C, Ponting CP, Liu JL. Mutagenesis and homologous recombination in Drosophila cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9. Biol Open. 2014;3:42–49. doi: 10.1242/bio.20137120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Böttcher R, Hollmann M, Merk K, Nitschko V, Obermaier C, Philippou-Massier J, Wieland I, Gaul U, Förstemann K. Efficient chromosomal gene modification with CRISPR/cas9 and PCR-based homologous recombination donors in cultured Drosophila cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, O’Connor-Giles KM. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–1035. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren X, Sun J, Housden BE, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, Liu LP, Yang Z, Mao D, Sun L, Wu Q, Ji JY, Xi J, Mohr SE, Xu J, Perrimon N, Ni JQ. Optimized gene editing technology for. Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19012–19017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318481110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett AR, Tibbit C, Ponting CP, Liu JL. Highly efficient targeted mutagenesis of Drosophila with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Rep. 2013;4:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebo ZL, Lee HB, Peng Y, Guo Y. A simplified and efficient germline-specific CRISPR/Cas9 system for Drosophila genomic engineering. Fly. 2014;8:52–57. doi: 10.4161/fly.26828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Z, Ren M, Wang Z, Zhang B, Rong YS, Jiao R, Gao G. Highly efficient genome modifications mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in Drosophila. Genetics. 2013;195:289–291. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.153825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Joung JK, Sander JD. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, Cradick TJ, Marraffini LA, Bao G, Zhang F. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, Ma E, Doudna JA, Liu DR. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren X, Yang Z, Xu J, Sun J, Mao D, Hu Y, Yang SJ, Qiao HH, Wang X, Hu Q, Deng P, Liu LP, Ji JY, Li JB, Ni JQ. Enhanced specificity and efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas9 system with optimized sgRNA parameters in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, Tothova Z, Hegde M, Smith I, Sullender M, Ebert BL, Xavier RJ, Root DE. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene inactivation. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T, Wei JJ, Sabatini DM, Lander ES. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science. 2014;343:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1246981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelsen TS, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, Zhang F. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujii W, Kawasaki K, Sugiura K, Naito K. Efficient generation of large-scale genome-modified mice using gRNA and CAS9 endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e187. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bae S, Kweon J, Kim HS, Kim JS. Microhomology-based choice of Cas9 nuclease target sites. Nat Methods. 2014;11:705–706. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindquist RA, Ottina KA, Wheeler DB, Hsu PP, Thoreen CC, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Shaul YD, Lamprecht MR, Madden KL, Papallo AR, Jones TR, Sabatini DM, Carpenter AE. Genome-scale RNAi on living-cell microarrays identifies novel regulators of Drosophila melanogaster TORC1–S6K pathway signaling. Genome Res. 2011;21:433–446. doi: 10.1101/gr.111492.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neumüller RA, Wirtz-Peitz F, Lee S, Kwon Y, Buckner M, Hoskins RA, Venken KJ, Bellen HJ, Mohr SE, Perrimon N. Stringent analysis of gene function and protein–protein interactions using fluorescently tagged genes. Genetics. 2012;190:931–940. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cherbas L, Moss R, Cherbas P. Transformation techniques for. Drosophila cell lines. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:161–179. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H, McManus C, Cho DY, Eaton M, Renda F, Somma M, Cherbas L, May G, Powell S, Zhang D, Zhan L, Resch A, Andrews J, Celniker SE, Cherbas P, Przytycka TM, Gatti M, Oliver B, Graveley B, MacAlpine D. DNA copy number evolution in Drosophila cell lines. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-8-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlson DF, Tan W, Lillico SG, Stverakova D, Proudfoot C, Christian M, Voytas DF, Long CR, Whitelaw CB, Fahrenkrug SC. Efficient TALEN-mediated gene knockout in livestock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17382–17387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211446109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard GF, Viterbo D, Khanna V, Mosbach V, Castelain L, Dujon B. Highly specific contractions of a single CAG/CTG trinucleotide repeat by TALEN in yeast. PLOS One. 2014;9:e95611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li K, Wang G, Andersen T, Zhou P, Pu WT. Optimization of genome engineering approaches with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. PLOS One. 2014;9:e105779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nobukini T, Thomas G. The mTOR/S6K signalling pathway: The role of the TSC1/2 tumour suppressor complex and the protooncogene Rheb. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;262:148–154. discussion 154–159, 265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1–TSC2 complex: A molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412:179–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guertin DA, Guntur KV, Bell GW, Thoreen CC, Sabatini DM. Functional genomics identifies TOR-regulated genes that control growth and division. Curr Biol. 2006;16:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Tuberous sclerosis: A GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(Spec No 2):R251–R258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tapon N, Ito N, Dickson BJ, Treisman JE, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila tuberous sclerosis complex gene homologs restrict cell growth and cell proliferation. Cell. 2001;105:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn S, Cowling VH. Myc and mRNA capping. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proud CG. Regulation of protein synthesis by insulin. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:213–216. doi: 10.1042/BST20060213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005;123:569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guruharsha KG, Rual J-F, Zhai B, Mintseris J, Vaidya P, Vaidya N, Beekman C, Wong C, Rhee DY, Cenaj O, McKillip E, Shah S, Stapleton M, Wan KH, Yu C, Parsa B, Carlson JW, Chen X, Kapadia B, VijayRaghavan K, Gygi SP, Celniker SE, Obar RA, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. A protein complex network of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 2011;147:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee S, Nahm M, Lee M, Kwon M, Kim E, Zadeh AD, Cao H, Kim H-J, Lee ZH, Oh SB, Yim J, Kolodziej PA, Lee S. The F-actin-microtubule crosslinker Shot is a platform for Krasavietz-mediated translational regulation of midline axon repulsion. Development. 2007;134:1767–1777. doi: 10.1242/dev.02842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiger AA, Baum B, Jones S, Jones MR, Coulson A, Echeverri C, Perrimon N. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J Biol. 2003;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lis JT, Mason P, Peng J, Price DH, Werner J. P-TEFb kinase recruitment and function at heat shock loci. Genes Dev. 2000;14:792–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkinson S, Croft DR, O’Prey J, Meedendorp A, O’Prey M, Dufes C, Ryan KM. The cyclin-dependent kinase PITSLRE/CDK11 is required for successful autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7:1295–1301. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.16646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parkhitko AA, Priolo C, Coloff JL, Yun J, Wu JJ, Mizumura K, Xu W, Malinowska IA, Yu J, Kwiatkowski DJ, Locasale JW, Asara JM, Choi AM, Finkel T, Henske EP. Autophagy-dependent metabolic reprogramming sensitizes TSC2-deficient cells to the antimetabolite 6-aminonicotinamide. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:48–57. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0258-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, Qin W, Klekota J, Asara JM, Finan PM, Kwiatkowski DJ, Murphy LO, Manning BD. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2012;47:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee PS, Tsang SW, Moses MA, Trayes-Gibson Z, Hsiao LL, Jensen R, Squillace R, Kwiatkowski DJ. Rapamycin-insensitive up-regulation of MMP2 and other genes in tuberous sclerosis complex 2–deficient lymphangioleiomyomatosis-like cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:227–234. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0050OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Medvetz D, Priolo C, Henske EP. Therapeutic targeting of cellular metabolism in cells with hyperactive mTORC1: A paradigm shift. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;13:3–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koelle MR, Talbot WS, Segraves WA, Bender MT, Cherbas P, Hogness DS. The drosophila EcR gene encodes an ecdysone receptor, a new member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Cell. 1991;67:59–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90572-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krejcí A, Bernard F, Housden BE, Collins S, Bray SJ. Direct response to Notch activation: Signaling crosstalk and incoherent logic. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bach EA, Ekas LA, Ayala-Camargo A, Flaherty MS, Lee H, Perrimon N, Baeg GH. GFP reporters detect the activation of the Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway in vivo. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sopko R, Foos M, Vinayagam A, Zhai B, Binari R, Hu Y, Randklev S, Perkins LA, Gygi SP, Perrimon N. Combining genetic perturbations and proteomics to examine kinase-phosphatase networks in Drosophila embryos. Dev Cell. 2014;31:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H, Cicchetti G, Onda H, Koon HB, Asrican K, Bajraszewski N, Vazquez F, Carpenter CL, Kwiatkowski DJ. Loss of Tsc1/Tsc2 activates mTOR and disrupts PI3K-Akt signaling through downregulation of PDGFR. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1223–1233. doi: 10.1172/JCI17222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li C, Lee PS, Sun Y, Gu X, Zhang E, Guo Y, Wu CL, Auricchio N, Priolo C, Li J, Csibi A, Parkhitko A, Morrison T, Planaguma A, Kazani S, Israel E, Xu KF, Henske EP, Blenis J, Levy BD, Kwiatkowski D, Yu JJ. Estradiol and mTORC2 cooperate to enhance prostaglandin biosynthesis and tumorigenesis in TSC2-deficient LAM cells. J Exp Med. 2014;211:15–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vizcaíno JA, Deutsch EW, Wang R, Csordas A, Reisinger F, Ríos D, Dianes JA, Sun Z, Farrah T, Bandeira N, Binz PA, Xenarios I, Eisenacher M, Mayer G, Gatto L, Campos A, Chalkley RJ, Kraus HJ, Albar JP, Martinez-Bartolomé S, Apweiler R, Omenn GS, Martens L, Jones AR, Hermjakob H. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.