Abstract

Objective

To determine the rates of and risk factors for tigecycline non-susceptibility among carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) isolated from hospitalized patients.

Design

Multicenter prospective observational study

Setting

Acute care hospitals participating in the Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRaCKle)

Patients

287 patients who had CRKP isolated from clinical cultures during hospitalization

Methods

Within the study period of 12/24/2011 – 10/1/2013, the first hospitalization of each patient with CRKP was included during which tigecycline susceptibility for the CRKP isolate was determined. Clinical data was entered into a centralized database, including data on pre-hospital origin. Breakpoints established by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) were used to interpret tigecycline susceptibility testing.

Results

Of 287 patients included, 155 (54%) had tigecycline-susceptible CRKP, whereas 81 (28%) of index isolates were tigecycline-intermediate, and 51 (18%) were tigecycline-resistant. In multivariable modeling, admission from a skilled nursing facility (OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.51–4.21, p=0.0004), positive culture within 2 days of admission (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.06–3.15, p=0.03), and receipt of tigecycline within 14 days (OR 4.38, 95% CI 1.37–17.01, p=0.02) were found to be independent risk factors for tigecycline non-susceptibility.

Conclusions

In hospitalized patients with CRKP, tigecycline non-susceptibility was more frequently seen in admissions from skilled nursing facilities and occurred earlier during hospitalization. Skilled nursing facilities are an important target for interventions to decrease antibacterial resistance to antibiotics of last resort for treatment of CRKP.

Introduction

The rise of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae poses a global threat to the accomplishments of modern medicine1,2. Advances in transplant medicine, surgery, and oncology are specifically at risk. The current treatment options for infections due to carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are very limited as most isolates are resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics. Antibacterials of last resort which are being used in the treatment of CRE include aminoglycosides, polymyxins, fosfomycin and tigecycline3. Novel antibiotics with activity against CRE are currently under study including the aminoglycoside plazomicin, and novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors such as ceftazidime/avibactam4,5. These compounds hold promise for more efficacious treatment of CRE infections combined with a more favorable side effect profile. However, development of resistance remains a concern for all current and future antibiotics as resistance may spread rapidly amongst Enterobacteriaceae through plasmids and other mobile genetic elements6.

Causes of resistance development to various antibiotics are likely to overlap. Therefore, variables associated with tigecycline resistance, which has been increasingly observed in CRE isolates, may inform strategies to limit development of resistance against newer agents. In this context, we decided to study variables associated with tigecycline resistance in the Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRaCKle).

METHODS

Patients

The current study represents a nested cohort within Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRaCKle) study, that was previously described7,8. Briefly, CRaCKle is a prospective, observational, multicenter study which aims to study patients who have positive cultures for CRKP during their hospitalization. This nested cohort consists of all hospitalized patients who had a clinical culture which grew CRKP during their hospitalization that was tested for tigecycline susceptibility. Patients were included if their index hospitalization began and ended in the study period 12/24/2011 – 10/1/2013. Patients were included once at the time of their first positive culture. Patients who were known to be colonized with CRKP were placed in contact isolation. The Institutional Review Boards of all health systems involved approved the study.

Microbiology

CRKP are defined as K. pneumoniae isolates with non-susceptibility to the following carbapenems as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines; meropenem, imipenem or ertapenem9. Bacterial identification and routine antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed with MicroScan (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) or Vitek2 (BioMerieux), supplemented by GN4F Sensititre tray (Thermo Fisher) to confirm carbapenem results and to test tigecycline susceptibility. The majority of CRKP in CRaCKle are confirmed to carry blaKPC, as previously described8. For interpretation of tigecycline MIC results breakpoints defined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) were used; susceptible, intermediate, and resistant defined as MIC <2 μg/mL, 2 μg/mL, and >2 μg/mL, respectively.

Clinical Data

Clinical data was obtained from the electronic medical record, and entered into a centralized database. The index hospitalization was designated as the first hospital stay within the study period during which CRKP was isolated when the CRKP isolate was tested for tigecycline susceptibility. Standardized criteria for CRKP infection were used, as previously described8. Briefly, CR-Kp was isolated from blood or any other sterile source represented infection. For patients with positive respiratory cultures the criteria outlined by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) were used10,11. For patients with positive cultures from urine or surgical wounds, the CDC/NHSN criteria were used12. Critical illness was defined as a Pitt bacteremia score greater or equal to 4 points, on the day of the index culture13. Charlson comorbidity index was calculated14. The onset was considered present on admission (POA) if the first positive culture for CRKP was obtained within 48 hours of hospitalization.

Analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous variables. Fisher’s Exact, and Pearson testing were used for categorical variables where appropriate. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed including all pre-culture variables that were associated with tigecycline non-susceptibility at the level of p<0.1 in univariate analysis. In addition, a multivariable ordinal logistic model was constructed to test associations with the ordinal outcome of tigecycline susceptibility (susceptible vs. intermediate vs. resistant). Analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

During the study period, 287 patients were included. Their demographics are listed in Table 1. In this nested cohort, patients tended to be elderly with a median age of 71 years (interquartile range [IQR] 59–81 years), 63% of patients were female, and 54% were white. Comorbidities were common; the median Charlson comorbidity index was 3 (IQR 2–5), and more than half of patients had diabetes mellitus. The majority of patients were admitted from skilled nursing facilities (SNF) (53%), but 27% were admitted from home.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| All | Tigecycline Susceptible |

Tigecycline Non-Susceptible |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 287 | 155 | 132 | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 71 (59–81) | 69 (57–79) | 72 (63–83) | 0.0512 |

| Gender, Female | 181 (63) | 93 (60) | 88 (67) | 0.2703 |

| Race | 0.6346 | |||

| White | 154 (54) | 87 (56) | 67 (51) | |

| Black | 118 (41) | 60 (39) | 58 (44) | |

| Other | 14 (5) | 8 (5) | 6 (5) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–6) | 0.0520 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 149 (52) | 73 (47) | 76 (58) | 0.0969 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 65 (23) | 36 (23) | 29 (22) | 0.8876 |

| Malignancy | 37 (13) | 19 (12) | 18 (14) | 0.7281 |

| Immunocompromised | 27 (9) | 18 (12) | 9 (7) | 0.2234 |

| Corticosteroids | 13 (5) | 5 (3) | 8 (6) | – |

| Solid organ transplant | 11 (4) | 10 (6) | 1 (1) | – |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplant | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | – |

| HIV infection | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 | – |

| Origin | <0.0001 | |||

| Skilled nursing facility | 153 (53) | 64 (41) | 89 (67) | |

| Home | 77 (27) | 49 (32) | 28 (21) | |

| Hospital transfer | 37 (13) | 30 (19) | 7 (5) | |

| Long term acute care | 20 (7) | 12 (8) | 8 (6) |

All data in n (%), unless otherwise indicated. IQR: interquartile range

Cultures and timing of onset

Culture data are summarized in Table 2. Urine (61%) was by far the most common anatomic source for positive CRKP cultures. Only 44/175 (25%) of urine cultures represented a UTI. Overall, 44% of all patients met criteria for CRKP infection. Critical illness was present in 32% of patients. Critical illness at the time of first positive culture was more common in patients with CRKP infection as compared to CRKP colonization; 56/127 (44%) of patients with infection were critically ill, as compared to 37/123 (23%) of patients with colonization (p=0.0002). Overall length of hospital stay was prolonged at a median of 10 days (IQR 6–18 days). Remarkably, most of this hospital stay took place after the first positive CRKP culture. The median time from admission to first positive CRKP was one day (IQR 0–5 days). In 184 (64%) of patients CRKP was deemed POA. In multivariable analysis, SNF origin, anatomic source, and critical illness were associated with CRKP that were POA. POA onset was more common in patients admitted from a SNF. POA onset was noted in 112/153 (73%) patients admitted from SNF vs. in 72/134 (54%) patients admitted from other venues (OR 2.53, 95%CI 1.49–4.35, p=0.0006). Using respiratory source (26%) as a reference, POA onset was noted for 73%, 64%, 59%, 44% of patients with urine (OR 6.07, 95%CI 2.50–16.00), wound (OR 3.84, 95%CI 1.29–12.28), blood (OR 4.36, 95%CI 1.54–13.30), other (OR 2.24, 95%CI 0.43–11.33) anatomic sources, respectively (p=0.0014). In patients with critical illness, POA onset was less common; 48% vs. 72% in patients without critical illness at the time of first CRKP positive culture (OR 0.43 95%CI 0.24–0.76, p=0.004).

Table 2.

Culture data.

| All | Tigecycline Susceptible |

Tigecycline Non-Susceptible |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 287 | 155 | 132 | |

| Source | 0.5238 | |||

| Urine | 175 (61) | 91 (59) | 84 (64) | |

| Blood | 39 (14) | 26 (17) | 13 (10) | |

| Wound | 33 (11) | 18 (11) | 15 (11) | |

| Respiratory | 31 (11) | 16 (10) | 15 (11) | |

| Other | 9 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | |

| Infection | 127 (44) | 74 (48) | 53 (40) | 0.2332 |

| Critically ill at time of culturea | 93 (32) | 54 (35) | 39 (30) | 0.3767 |

| Patient location at time of culture | 0.3950 | |||

| Ward | 119 (41) | 69 (45) | 50 (38) | |

| Intensive care unit | 91 (32) | 49 (32) | 42 (32) | |

| Emergency department | 77 (27) | 37 (24) | 40 (30) | |

| Present on admissionb | 184 (64) | 89 (57) | 95 (72) | 0.0134 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 10 (6–18) | 12 (7–23) | 8 (5–14) | 0.0015 |

All data in n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

as defined by Pitt bacteremia score≥4 on the day of first positive culture.

defined as a positive culture within within 48 hours of hospitalization. IQR: interquartile range

Prior antibiotic exposure

Antibiotics used in the 14-day period preceding the first positive CRKP culture are outlined in Table 3. In the cohort as a whole, 39% of patients received at least one antibiotic in that period. The most common antibiotic used was vancomycin, which was administered to 30% of patients in the 14 days leading up to the first positive CRKP culture. Use of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors (22%) and fluoroquinolones (18%) were common as well. Prior use of tigecycline was uncommon, only 6% of patients had received tigecycline.

Table 3.

Exposure to antibiotics in 14 days prior to first positive culture.

| All | Tigecycline Susceptible |

Tigecycline Non-Susceptible |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 287 | 155 | 132 | |

| Exposure to any antibiotic in 14 days prior to cultures | 111 (39) | 56 (36) | 55 (42) | 0.3947 |

| Tigecycline | 16 (6) | 4 (3) | 12 (9) | 0.0201 |

| Carbapenem | 44 (15) | 28 (18) | 16 (12) | 0.1899 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 53 (18) | 30 (19) | 23 (17) | 0.7607 |

| Colistin | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Vancomycin | 87 (30) | 47 (30) | 40 (30) | 1.000 |

| β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor | 62 (22) | 36 (23) | 26 (20) | 0.5651 |

| Cephalosporin | 27 (9) | 15 (10) | 12 (9) | 1.000 |

| Aminoglycoside | 18 (6) | 10 (6) | 8 (6) | 1.000 |

| Metronidazole | 13 (5) | 7 (5) | 6 (5) | 1.000 |

| Daptomycin | 14 (5) | 9 (6) | 5 (4) | 0.5844 |

| Other | 76 (26) | 48 (31) | 28 (21) | 0.0807 |

| Number of classes of antibiotics | 0.6796 | |||

| None | 111 (39) | 56 (36) | 55 (42) | |

| One | 52 (18) | 28 (18) | 24 (18) | |

| Two | 58 (20) | 35 (23) | 24 (18) | |

| more than two | 66 (23) | 36 (23) | 30 (23) |

All data in n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Tigecycline susceptibility

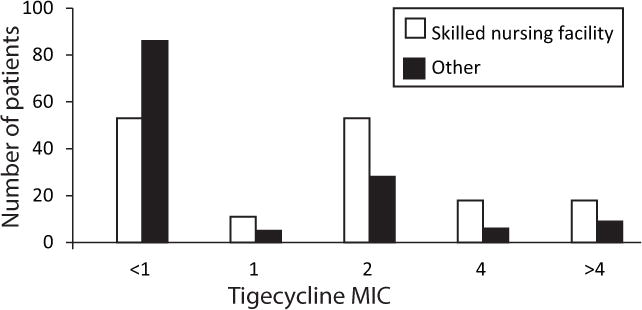

At the time of their index culture, 132/287 (46%, 95%CI 40%–52%) of patients presented with a tigecycline non-susceptible CRKP isolate. The distribution of MICs for tigecycline is shown in Figure 1. Using univariable analysis, origin prior to admission was strongly associated with tigecycline susceptibility (p<0.0001). Admission from a skilled nursing facility was then compared to all other points of origin prior to hospitalization in multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 4). In contrast, admission from LTAC was not associated with tigecycline non-susceptibility (data not shown). In this model, admission from a skilled nursing facility (OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.51–4.21, p=0.0004), POA onset (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.06–3.15, p=0.03), and receipt of tigecycline within 14 days (OR 4.38, 95% CI 1.37–17.01, p=0.02) were found to be independent risk factors for tigecycline non-susceptibility. An ordinal logistic regression model was also constructed for the ordinal outcome of tigecycline susceptibility (i.e. susceptible vs. intermediate vs. resistant). In this model, the same variables were also found to be associated with the ordinal outcome; admission from a skilled nursing facility (p=0.0005), POA onset (p=0.0064), and receipt of tigecycline within 14 days (p=0.0094). After stratification by CRKP infection vs. colonization, admission from a skilled nursing facility remained independently associated with tigecycline non-susceptibility in multivariable analysis (OR 3.61, 95% CI 1.59–8.53, p=0.002 in patients with CRKP infection, and OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.18–4.86, p=0.015 in patients with CRKP colonization).

Figure 1.

Tigecycline minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates by origin prior to hospitalization.

Table 4.

Risk factors for tigecycline non-susceptibility.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission from skilled nursing facility | 2.52 | 1.51–4.24 | 0.0004 |

| Present on admission | 1.77 | 1.03–3.08 | 0.038 |

| Receipt of tigecycline within 14 days | 4.41 | 1.36–17.24 | 0.012 |

Multivariable logistic regression model which also included age, Charlson score and presence of diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

In this defined cohort, predictors of tigecycline non-susceptibility in patients with CRKP include: i) admission from a skilled nursing facility ii) having an early onset of positive culture within the hospital stay; and iii) receipt of tigecycline in the previous 14 days. When the impact of treatment of CRKP bacteriuria on the development of tigecycline resistance was previously evaluated, we found that tigecycline treatment of the index CRKP bacteriuria was strongly associated with risk for subsequent development of tigecycline resistance (OR 6.13, 95%CI 1.15–48.65, p=0.03)7. In addition, this resistance was found to develop rapidly at a median of 65 days7. Nigo et al. evaluated the development of tigecycline resistance in multi-drug resistant K. pneumoniae (60% of these were CRKP) in a retrospective single-center case-control study15. They also found that tigecycline exposure was associated with the subsequent development of tigecycline resistance (OR 5.06; 95% CI, 1.80 to 14.23; p=0.002)15. They did not evaluate origin prior to hospitalization.

Patients admitted from a nursing home who had a positive culture on the first or second day of hospitalization were at the highest risk of having a tigecycline-non-susceptible CRKP isolate. This finding implies that these patients came in colonized with CRKP before their hospitalization. While we cannot establish in this study where the origin is of tigecycline-non-susceptible CRKP, these findings are suggestive that either transmission of these isolates and/or de novo resistance mutations occur outside of the acute care setting.

In our cohort, the majority of patients with CRKP are older adults admitted from skilled nursing facilities. The presence of CRKP has been described in skilled nursing facilities outside of the US16,17. Within the US, CRKP has been isolated from patients transferred from LTACs and other LTCFs that provide mechanical ventilation, but recovery from patients transferred from skilled nursing facilities has been infrequently reported18,19. The findings from the current study suggest that CRKP might have disseminated throughout skilled nursing facilities to a greater degree than has been previously described.

The number of Americans living in nursing homes continues to increase and is currently estimated around 3 million people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that about 1 to 3 million serious infections occur in these patients annually, and that as many as 380,000 people die of these infections per year20. Most nursing home residents receive at least one course of antibiotics per year, and most courses exceed 7 days21,22. In addition, other risk factors for acquiring multi-drug resistant organisms are prevalent in this population as well, including frequent use of indwelling devices such as urinary catheters, chronic wounds, advanced age, and comorbidities23.

The findings presented here suggest that nursing homes should be an increasingly important area of research and implementation of preventative strategies including infection control and antimicrobial stewardship to curtail the spread of resistance to antibiotics of last resort in CRE. Currently, tigecycline, polymyxins such as colistin, and aminoglycosides given as monotherapy or in combination with carbapenems are believed to represent the cornerstone of treatment of CRE infections3,24. Novel agents including novel aminoglycosides such as plazomicin and various β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are currently under study and will hopefully become available for widespread clinical use soon4,5. As the first of such agents, ceftazidime/avibactam was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, resistance to these agents will likely develop over time as well, and is likely to be related to similar risk factors23. Therefore, taking action to limit spread of tigecycline resistant isolates will likely limit resistance development to novel anti-CRE antimicrobials as well. Worryingly, resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam has already been reported in Pseudomonas aeruginosa25

The main limitation of this study is that nursing homes are not part of CRaCKle. Rather, we are monitoring the impact of nursing homes by comprehensively monitoring all hospitalized patients with positive cultures for CRKP. Therefore, we are examining the “tip of the iceberg” and are missing those nursing home residents with rectal CRKP carriage, who are not admitted to the hospital or who have no clinical cultures positive for CRKP. Follow-up studies are needed that examine this issue directly in the nursing home. However, this multi-center consortium covers the great majority of hospitals in the region and by employing a comprehensive inclusion strategy, we have an unbiased cohort. In addition, these are the patients who confront acute care physicians. Another limitation of this study is that data on prior antibiotic usage was evaluated only for the 14-day period prior to the first positive CRKP culture. Only antibiotics reported either in notes or medication lists of the electronic medical record were included which may have led to an underestimation of antibiotic usage. However, in an independent cohort, tigecycline use also was the only antibacterial independently associated with tigecycline resistance15. This validates our finding that tigecycline use is a major driver of tigecycline resistance development. While this is intuitive, it is important to note that for other MDRO, a direct link is not always the main driver of resistance; for instance ceftriaxone use rather than vancomycin use was shown to be related to vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium26. Finally, only patients with isolates that were clinically tested for tigecycline susceptibility were included, which may have resulted in an over-estimate of tigecycline non-susceptibility. However, the majority of CRKP isolates in CRACKLE are routinely tested for tigecycline susceptibility.

In summary, in this multi-center, prospective cohort of hospitalized patients with CRKP, patients with tigecycline non-susceptible isolates were found to be similar in most respects to patients with tigecycline susceptible CRKP. The three variables associated with decreased tigecycline susceptibility were previous tigecycline exposure, admission from a nursing home setting, and a positive culture for CRKP within the first 2 days of hospitalization. These findings emphasize the need for antimicrobial stewardship, as well as the urgent need for evaluation of optimal infection control practices in long term care.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support. This work was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1AI104681, and by funding to DVD and FP from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. VGF was supported by Mid-Career Mentoring Award K24-AI093969 from NIH. In addition, this work was supported in part by the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (RAB), the National Institutes of Health (Grant AI072219-05 and AI063517-07 to RAB), and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10 (RAB), the Research Program Committees of the Cleveland Clinic (DVD), an unrestricted research grant from the STERIS Corporation (DVD). KSK is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, DMID protocol 10-0065.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. DvD has received research funding from Steris and Scynexis, has served on the Speaker’s Bureau for Astellas, on a drug safety monitoring board for Pfizer, on a consultancy board for Sanofi Pasteur, and as editor for Medstudy. RAB has received research funding from Astra Zeneca, Merck and Checkpoints and has served on a Tetraphase drug safety monitoring board. SSR has received research funding from bioMerieux, Nanosphere, BD Diagnostics, Biofire, Pocared, and Forest. All other authors: none to declare.

Disclaimer. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Perez F, van Duin D. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a menace to our most vulnerable patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:225–233. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Duin D, Kaye KS, Neuner EA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;75:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Jones RN. Ceftazidime/avibactam activity tested against Gram-negative bacteria isolated from bloodstream, pneumonia, intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections in US medical centres (2012) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1589–1598. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walkty A, Adam H, Baxter M, et al. In Vitro Activity of Plazomicin against 5,015 Gram-Negative and Gram- Positive Clinical Isolates Obtained from Patients in Canadian Hospitals as Part of the CANWARD Study, 2011–2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2554–2563. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02744-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers AJ, Cox HL, Kitchel B, et al. Molecular dissection of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae reveals Intergenus KPC carbapenemase transmission through a promiscuous plasmid. MBio. 2011;2:e00204–00211. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00204-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Duin D, Cober E, Richter S, et al. Tigecycline Therapy for Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) Bacteriuria Leads to Tigecycline Resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, et al. Surveillance of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Tracking Molecular Epidemiology and Outcomes through a Regional Network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4035–4041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02636-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Fourth Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S24. 2014;34 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections. CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections. 2014 Available at: www.cdc.gov/nhsn.

- 13.Chow JW, Yu VL. Combination antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for gram-negative bacteraemia: a commentary. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigo M, Cevallos CS, Woods K, et al. Nested case-control study of the emergence of tigecycline resistance in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5743–5746. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00827-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prabaker K, Lin MY, McNally M, et al. Transfer from High-Acuity Long-Term Care Facilities Is Associated with Carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: A Multihospital Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1193–1199. doi: 10.1086/668435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchaim D, Chopra T, Bogan C, et al. The burden of multidrug-resistant organisms on tertiary hospitals posed by patients with recent stays in long-term acute care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-David D, Maor Y, Keller N, et al. Potential role of active surveillance in the control of a hospital-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:620–626. doi: 10.1086/652528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler A, Hussein O, Ben-David D, et al. Persistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 as the predominant clone of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in post-acute-care hospitals in Israel, 2008–13. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:89–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014:2014. http://www.cdc.gov/longtermcare/ Accessed 11/13/2014.

- 21.Daneman N, Gruneir A, Bronskill SE, et al. Prolonged antibiotic treatment in long-term care: role of the prescriber. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:673–682. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daneman N, Gruneir A, Newman A, et al. Antibiotic use in long-term care facilities. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2856–2863. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safdar N, Maki DG. The commonality of risk factors for nosocomial colonization and infection with antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, enterococcus, gram-negative bacilli, Clostridium difficile, and Candida. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:834–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tumbarello M, Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Bloodstream Infections Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. pneumoniae: Importance of Combination Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:943–950. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler ML, Papp-Wallace KM, Hujer AM, et al. Unexpected Challenges in Treating Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Resistance to Ceftazidime-Avibactam in Archived Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1020–1029. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04238-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinnell JA, Kunz DF, Chamot E, et al. Association between vancomycin-resistant Enterococci bacteremia and ceftriaxone usage. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:718–724. doi: 10.1086/666331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]