Abstract

The commonly used para-nitrobenzenesulfonyl (nosyl) protecting group is employed to direct the C–H activation of amines for the first time. An enantioselective ortho-C–H cross-coupling between nosyl-protected diarylmethylamines and arylboronic acid pinacol esters has been achieved utilizing chiral mono-N-protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands as a promoter.

Keywords: enantioselective catalysis, amine-directed C–H activation, C–H coupling, palladium, amino acid ligand

Despite extensive efforts to develop C–H activation reactions of broadly useful substrates using weak coordination,[1] design of practical directing groups for amines has been met with limited success. While triflyl-protected amines have demonstrated a relatively broad scope of both substrates (benzylamines, phenylethylamines, propyl amines) and transformations (iodination, olefination, fluorination and amination),[2] the use of expensive and corrosive triflic anhydride for installation of the triflyl moiety, as well as the relatively harsh procedures required for removal, [2a,c] limits its appeal as a synthetically useful directing group. Alternative two-step deprotection conditions have been developed, but have proven incompatible with compounds bearing acidic α-hydrogens due to the potential for deprotionation, which could lead to a variety decomposition pathways.[2e–g] The recent success in development of enantioselective iodinations of triflyl-protected amines via desymmetrization and kinetic resolution[2e,f] has provided us incentive to seek a practical directing group for amine substrates to allow for rapid synthesis of valuable chiral amine scaffolds.[3] Although there have been a few reports of Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H arylation reactions directed by free-[4] and tertiary amines,[5] the scope of these transformations is limited due to the strongly acidic conditions required,[4a,b] and the use of directing groups that cannot be easily removed.[5] The development of C–H activation reactions of amines employing commonly used synthetic protecting groups is a prerequisite for broad applications of C–H activation in amine synthesis. To the best of our knowledge there are no known protocols for the directed C–H functionalization of the commonly employed nosyl-protected amine (nosyl = para-nitrobenzenesulfonyl), due to a lack of reactivity of the nosylamide under a variety of previously developed C–H activation conditions.[6] Herein, we report a ligand-promoted enantioselective ortho-C–H coupling of nosyl-protected diarylmethylamines with arylboronic acid pinacol esters, adding a valuable example to the intensively pursued development of enantioselective C–H activation reactions.[7,8] The newly established reactivity of nosylamides also paves the way for further development of practical C–H activation transformations of amines.

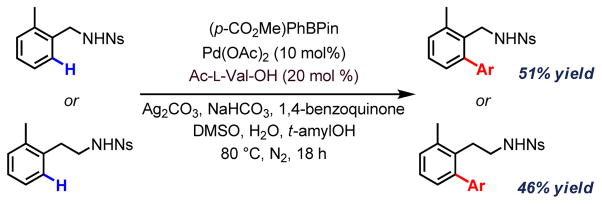

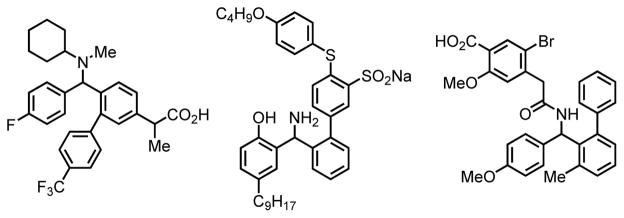

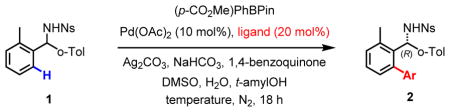

As illustrated in Scheme 1, we initiated our studies by attempting the nosylamide-directed C(sp2)–H arylation of simple benzyl- and phenethylamines. From these preliminary experiments, we were delighted to find that nosyl-protected amines indeed proved to be viable directing groups for C–H activation. Similar to the triflamide-directed C–H coupling,2g the use of NaHCO3 is required to deprotonate the sulfonamide for coordination. Ag2CO3 acts as both oxidant for the reoxidation of Pd(0) and promoter for the coupling step. DMSO prevents Pd(0) species from aggregation. Since chiral diarylmethylamines are known to be medicinally important scaffolds, with ortho-substituted diarylamines in particular having been known to display a range of bioactivity including γ-secretase modulation and HPV inhibition (Figure 1),[9,10] we redirected our focus towards the enantioselective cross-coupling of prochiral diarylmethylamine 1 with para-methoxycarbonylphenylboronic acid pinacol ester.

Scheme 1.

Nosyl-directed C(sp2)–H activation.

Figure 1.

Bioactive ortho-aryl diarylmethylamines.

We were pleased to find that inclusion of the MPAA ligand Ac-Ala-OH afforded desired arylated product 2 in 62% yield and 76% ee. After an extensive survey of readily available MPAA ligands (see Supporting Information), we quickly narrowed down our options to carbamate-protected, aliphatic amino acids. As shown in Table 1, Fmoc-Val-OH provided 2 in 65% yield, and 89% ee (entry 3). Lower temperatures (80°C) could also be employed without sacrificing reaction efficiency (entry 8, 63% yield, 91% ee). In addition, by substituting the acid moiety of the ligand with an N-methoxyamide, a noticeable boost in both yield and enantioselectivity was observed (entry 9, 83% yield, 96% ee). It was quickly found that Fmoc-Leu-NHOMe proved to be the optimal ligand for this enantioselective cross-coupling protocol (entry 10, 90% yield, 96% ee).

Table 1.

Ligand Evaluation[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Temp. (°C) | Yield (%)[b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1 | Ac-L-Val-OH | 100 | 62 | 76 |

| 2 | Boc-L-Val-OH | 100 | 66 | 84 |

| 3 | Fmoc-L-Val-OH | 100 | 65 | 89 |

| 4 | Troc-L-Val-OH | 100 | 43 | 88 |

| 5 | Boc-L-Leu-OH | 100 | 71 | 90 |

| 6 | Boc-L-Phe-OH | 100 | 67 | 87 |

| 7 | Fmoc-L-Ala-OH | 100 | 63 | 89 |

| 8 | Fmoc-L-Val-OH | 80 | 63 | 91 |

| 9 | Fmoc-L-Val-NHOMe | 80 | 83 | 96 |

| 10[d] | Fmoc-L-Leu-NHOMe | 80 | 90 | 96 |

Reaction conditions: 0.1 mmol of substrate, 2 equiv ArBPin, 0.1 equiv Pd(OAc)2, 0.2 equiv ligand, 2.5 equiv Ag2CO3, 6 equiv NaHCO3, 0.5 equiv 1,4-benzoquinone, 10 μL H2O, 2.8 μL DMSO, 1 mL t-amylOH.

Yield determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3-benzodioxole as an internal standard.

Enantioselectivity determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

0.15 equiv ligand.

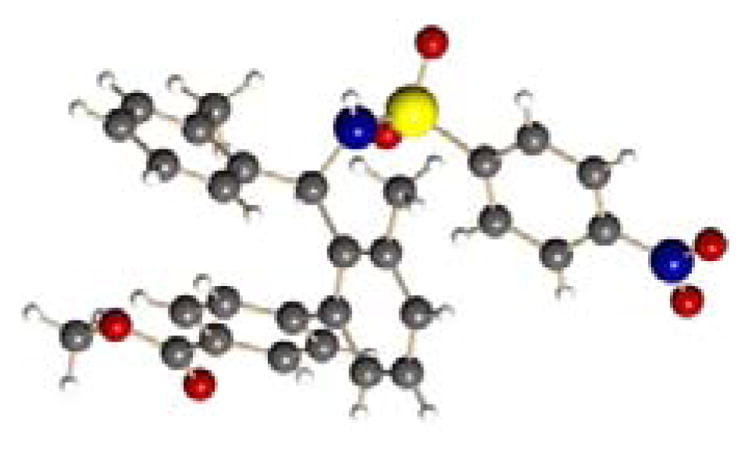

The absolute configuration of arylated product 2 was determined by X-ray crystallography (Figure 2). The observed enantioselectivity is rationalized with stereochemical model analogous to one previously proposed,[2e,11] wherein the deprotonated anionic sulfonaimine coordinates to the palladium(II) center via the imine moiety, facilitating selective C–H cleavage.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of (R)-2a.

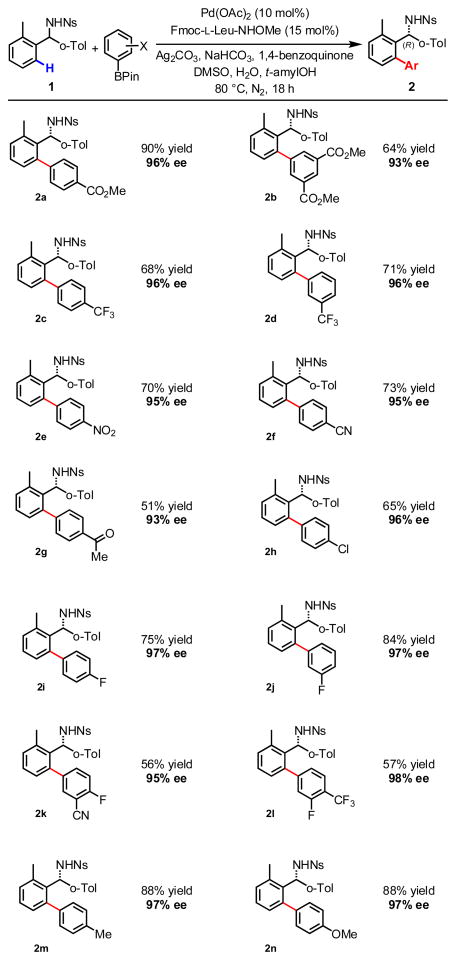

With optimized conditions in hand, we next investigated the scope of the arylboronic acid coupling partner. As demonstrated in Scheme 2, a variety of arylboron reagents coupled smoothly to provide arylated products with excellent levels of enantioselectivity. Trifluoromethyl-, nitro-, and nitrile-substituted arylborons afforded the desired products in good yield (2c–f; 68–73% yield, 95–96% ee), and both esters and ketones proved stable under the reaction conditions (2a, 2b, 2g; 64–90% yield, 93–96% ee). Furthermore, halogen substitution was also well tolerated, as evidenced by arylated products 2h–j bearing chlorine and fluorine atoms (65–84% yield, 96–97% ee). Electron-rich arylboronic acid pinacol esters also performed well in this reaction (2m, 2n; both 88% yield, 97% ee), as did di-substituted electron-deficient arylborons (2b, 2k, 2l).

Scheme 2.

Arylboronic acid pinacol ester scope. [a] Reaction conditions: 0.1 mmol of substrate, 2 equiv ArBPin, 0.1 equiv Pd(OAc)2, 0.2 equiv ligand, 2.5 equiv Ag2CO3, 6 equiv NaHCO3, 0.5 equiv 1,4-benzoquinone, 10 μL H2O, 2.8 μL DMSO, 1 mL t-amylOH. [b] Isolated yield. [c] Enantioselectivity determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

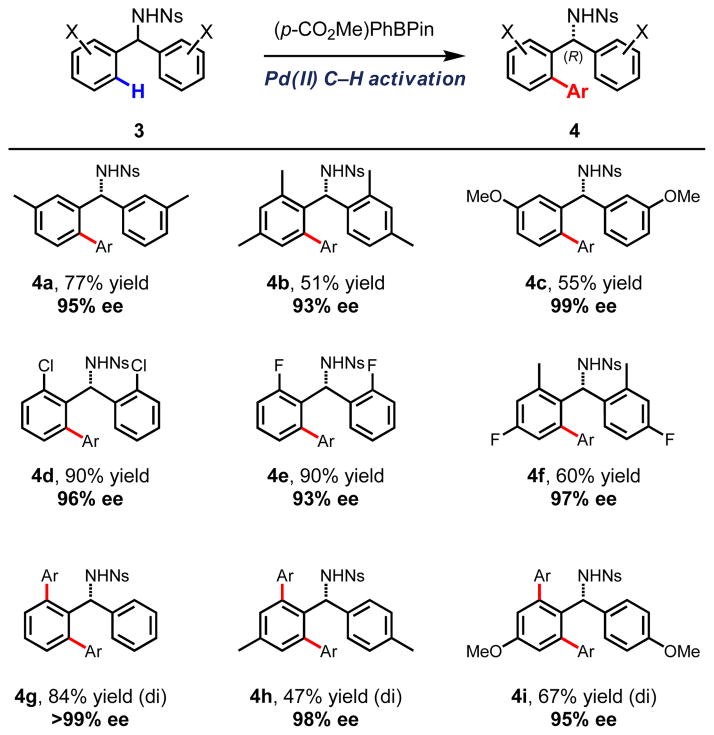

We also examined the scope of the diarylmethylamines (Scheme 3). Substitution on the diarylmethylamine was well tolerated, allowing for both electron-rich and electron-deficient substrates to readily undergo cross-coupling with high levels of enantioselectivity. Halogenated diarylmethylamines also underwent coupling smoothly (entries 4d–4f, 60–90% yield, 93–97% ee). Both ortho- and meta-substituted substrates provided mono-arylated products; however, unsubstituted or para-substituted substrates led predominantly to di-arylation (entries 4g–4i, 47–84% yield of di-arylated products).

Scheme 3.

Diarylmethylamine substrate scope. [a] Reaction conditions: 0.1 mmol of substrate, 2 equiv ArBPin, 0.1 equiv Pd(OAc)2, 0.2 equiv Fmoc-L-Leu-NHOMe, 2.5 equiv Ag2CO3, 6 equiv NaHCO3, 0.5 equiv 1,4-benzoquinone, 10 μL H2O, 2.8 μL DMSO, 1 mL t-amylOH. [b] Isolated yield. [c] Enantioselectivity determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

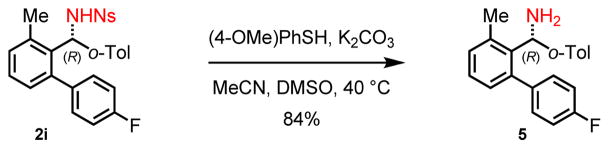

In order to demonstrate the synthetic utility of the para-nitrobenzenesulfonamide directing group, we next sought to remove the nosyl moiety from the arylated product under mildly basic conditions with gentle heating.[12] As illustrated in Scheme 4, deprotection proceeded smoothly in the presence of para-methoxythiophenol and potassium carbonate at 40 °C to afford the corresponding free amine 5 in 84% yield.

Scheme 4.

Deprotection of nitrobenzenesulfonyl protecting group.

In conclusion, we have developed an enantioselective cross-coupling of diarylmethylamine C(sp2)–H bonds and arylboronic acid pinacol esters, using chiral amino acids and N–methoxyamides as asymmetric ligands. Notably, this protocol exploits the synthetically practical and easily deprotected para-nitrobenzenesulfonamide as a directing group. Further development of C–H functionalizations directed by nosyl-protected amines and other widely used protecting groups is currently underway in our laboratory.

Experimental Section

General procedure for the enantioselective arylation of nosyl-protected diarylmethylamines: nosylamide substrate (0.1 mmol), aryl boronic acid pinacol ester (2 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.1 equiv), amino acid ligand (0.15 equiv), NaHCO3 (6 equiv), Ag2CO3 (2 equiv), and 1,4-benzoquinone (0.5 equiv) were added to a sealable Schlenk tube, and a solution of H2O (10 mL) and DMSO (2.8 mL) in t-AmOH (1 mL), and the reaction vessel was evacuated and backfilled with N2 (3 ×). The Schlenk tube was sealed, and the mixture stirred vigorously at 80 °C. After 18 h, the reaction was cooled to room temperature, EtOAc was added (5 mL), and the reaction was filtered through a pad of Celite over a plug of silica gel, and eluted with EtOAc (30 mL). The crude solution was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue purified via preparative thin layer chromatography to produce the corresponding chiral amines as white or pale yellow solids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge The Scripps Research Institute and the NIH (NIGMS, 2R01GM084019) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx

References

- 1.Engle KM, Mei T-S, Wasa M, Yu J-Q. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:788–802. doi: 10.1021/ar200185g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Li JJ, Mei TS, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6452–6455. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang X, Mei TS, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7520–7521. doi: 10.1021/ja901352k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mei T-S, Wang X, Yu J-Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10806–10807. doi: 10.1021/ja904709b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Vickers CJ, Mei TS, Yu JQ. Org Lett. 2010;12:2511–2513. doi: 10.1021/ol1007108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chu L, Wang X-C, Moore CE, Rheingold AL, Yu J-Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16344–16347. doi: 10.1021/ja408864c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chu L, Xiao KJ, Yu JQ. Science. 2014;346:451–455. doi: 10.1126/science.1258538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Chan KSL, Wasa M, Chu L, Laforteza BN, Miura M, Yu JQ. Nature Chem. 2014;6:146–150. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For a review on synthesis of chiral diarylmethylamines, see: Schmidt F, Stemmler RT, Rudolph J. C Bolm, Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:454–470. doi: 10.1039/b600091f.For a review on the use of tert-butanesulfinamide as a chiral auxiliary for asymmetric additions into imines, see: Robak MT, Herbage MA, Ellman JA. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3600–3740. doi: 10.1021/cr900382t.For a review on the synthesis of chiral amines via addition into imines, see: Kobayashi S, Mori Y, Fossey JS, Salter MM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:2626–2704. doi: 10.1021/cr100204f.For applications of tert-butanesulfinamide in the synthesis of diarylmethylamines, see: Pflum DA, Krishnamurthy D, Han Z, Wald SA, Senanayake CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:923–926.Plobeck N, Powell D. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:303–310.Weix DJ, Shi Y, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1092–1093. doi: 10.1021/ja044003d.Bolshan Y, Batey RA. Org Lett. 2005;7:1481–1484. doi: 10.1021/ol050014f.Boebel TA, Hartwig JF. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6824–6830.

- 4.For examples of Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H arylations directed by free amines (RNH2), see: Lazareva A, Daugulis O. Org Lett. 2006;8:5211–5213. doi: 10.1021/ol061919b.Liang Z, Feng R, Yin H, Zhang Y. Org Lett. 2013;15:4544–4547. doi: 10.1021/ol402207g.Liang Z, Yao J, Wang K, Li H, Zhang Y. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:16825–16831. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301229.Miura M, Feng CG, Ma S, Yu JQ. Org Lett. 2013;15:5258–5261. doi: 10.1021/ol402471y.

- 5.Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations directed by tertiary amines (R3N), see: Cai G, Fu Y, Li Y, Wan X, Shi Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7666–7673. doi: 10.1021/ja070588a.Gao DW, Shi YC, Gu Q, Zhao ZL, You SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:86–89. doi: 10.1021/ja311082u.Feng R, Yao J, Liang Z, Liu Z, Zhang Y. J Org Chem. 2013;78:3688–3696. doi: 10.1021/jo400186p.Tan PW, Haughey M, Dixon DJ. Chem Commun. 2015;51:4406–4409. doi: 10.1039/c5cc00410a.

- 6.For select examples of Pd(II)-catalyzed arylations directed by specific directing groups, see: Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4046–4048. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500589.Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13154–13155. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f.Yang S, Li B, Wan X, Shi Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6066–6067. doi: 10.1021/ja070767s.Haffemayer B, Gulias M, Gaunt MJ. Chem Sci. 2011;2:312–315.Nadres ET, Santos GIF, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J Org Chem. 2013;78:9689–9714. doi: 10.1021/jo4013628.Rodríguez N, Romero-Revilla JA, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ, Carretero JC. Chem Sci. 2013;4:175–179.Han J, Liu P, Wang C, Wang Q, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Shi D, Huang Z, Zhao Y. Org Lett. 2014;16:5682–5685. doi: 10.1021/ol502745g.

- 7.For Pd(0)-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C–H arylation: Albicher MR, Cramer N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9139–9142. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905060.Nakanishi M, Katayev D, Besnard C, Kündig EP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7438–7441. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102639.Anas S, Cordi A, Kagan HB. Chem Commun. 2011;47:11483–11485. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14292e.Martin N, Pierre C, Davi M, Jazzar R, Baudoin O. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:4480–4484. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200018.Shintani R, Otomo H, Ota K, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7305–7308. doi: 10.1021/ja302278s.

- 8.For atropselective C–H activation with moderate enantioselectivities: Kakiuchi F, Le Gendre P, Yamada A, Ohtaki H, Murai S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:2647–2651.Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi J, Studer A, Itami K. Chem Sci. 2012;3:2165–2169.

- 9.For examples of medicinally relevant compounds bearing chiral diarylmethylamines, see: Spencer CM, Foulds D, Peters DH. Drugs. 1993;46:1055–1080. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199346060-00008.Bishop MJ, McNutt RW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;5:1311–1314.Bilsky EJ, Calderon SN, Silvia N, Wang T, Bernstein RN, Davis P, Hruby VJ, McNutt RW, Rothman RB, Rice KC, Porreca F. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:359–366.Sakurai S, Ogawa N, Suzuki T, Kato K, Ohashi T, Yasuda S, Kato H, Ito Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 1996;44:765–777. doi: 10.1248/cpb.44.765.Plobeck N, Delorme D, Wei ZY, Yang H, Zhou F, Schwarz P, Gawell L, Gagnon H, Pelcman B, Schmidt R, Yue SY, Walpole C, Brown W, Zhou E, Labarre M, Payza K, Stönge S, Kamassah A, Morin PE, Projean D, Ducharme J, Roberts E. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3878–3894. doi: 10.1021/jm000228x.

- 10.a) Tsantrizos YS, Faucher A-M, Rancourt J, White P. 2004108673. WO. 2004; b) Sato S, Nakamura T, Nara F, Yonesu K. 2005120047. JP. 2005; c) Peng H, Cuervo J, Ishchenko A, Kumaravel G, Lee W-C, Lugovskoy A, Talreja T, Taveras A, Xin Z. 2010138901. WO. 2010

- 11.Cheng G-J, Yang Y-F, Liu P, Chen P, Sun T-Y, Li G, Zhang X, Houk KN, Yu J-Q, Wu Y-D. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:894. doi: 10.1021/ja411683n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cranfill DC, Lipton MA. Org Lett. 2007;9:3511–3513. doi: 10.1021/ol071350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.