Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder of mid-life onset characterized by involuntary movements and progressive cognitive decline caused by a CAG repeat expansion in exon 1 of the Huntingtin (Htt) gene. Neuronal DNA damage is one of the major features of neurodegeneration in HD but it is not known how it arises or relates to the triplet repeat expansion mutation in the Htt gene. Herein, we found that imbalanced levels of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated BRCA1 contribute to the DNA damage response in HD. Notably, nuclear foci of γ-H2AX, the molecular component that recruits various DNA damage repair factors to damage sites including BRCA1 were dysregulated when DNA was damaged in HD cell lines. BRCA1 specifically interacted with γ-H2AX via the BRCT domain and this association was reduced in HD. BRCA1 overexpression restored γ-H2AX level in the nucleus of HD cells while BRCA1 knockdown reduced the spatiotemporal propagation of γ-H2AX to the nucleoplasm. The deregulation of BRCA1 correlated with an abnormal nuclear distribution of γ-H2AX in striatal neurons of HD transgenic (R6/2) mice and BRCA1+/− mice. Our data indicate that BRCA1 is required for the efficient focal recruitment of γ-H2AX to the sites of neuronal DNA damage. Taken together, BRCA1 directly modulates the spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX upon genotoxic stress and serves as a molecular maker for neuronal DNA damage response in HD.

Keywords: DNA damage, BRCA1, H2AX, neurodegeneration, Huntington’s disease

INTRODUCTION

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by chorea and progressive cognitive impairment caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the exon 1 of the Huntingtin (Htt) gene. Cumulative neuronal DNA damage due to impaired DNA repair mechanisms is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of HD and other neurodegenerative disorders (Kovtun et al. 2007; Copped and Migliore 2010) but the potential role of the DNA damage response (DDR) in the pathogenesis of HD is not understood.

The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 encodes a large phosphoprotein involved in multiple nuclear functions, including DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and chromatin remodeling (Scully et al. 1997; for review see Venkitaraman 2001; Deng and Wang 2003; Starita and Parvin 2003; Ljungman and Lane 2004). BRCA1 is phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner and several phosphorylation sites have been identified under these conditions, including Ser-988, -1423, -1387, and -1524 (Chen et al. 1996; Ruffner and Verma 1997). In response to DNA damage, the BRCA1 protein becomes rapidly hyperphosphorylated at multiple sites by several kinases including ATM, a gene mutated in the ataxia telangiectasia syndrome. Mutation of the BRCA1 target sites for ATM, serines 1423 and 1524, abolishes the ability of BRCA1 to mediate the G2/M checkpoint, while mutation at serine 1387 disrupts the S-phase checkpoint. Interestingly, overexpression of wild type BRCA1 confers weak resistance to DNA damage-induced cell death in BRCA1 mutant breast cancer cell lines whereas phosphorylation-defective BRCA1 alleles carrying Ser to Ala substitution of these residues do not rescue them from apoptosis (Cortez et al. 1999; Scully et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2000). Thus, DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of BRCA1 is an intraceullar signal that orchestrates cell survival and death pathways. Mutations of mouse BRCA1 using various gene-targeting constructs that introduce null, hypomorphic and tissue-specific mutations result in embryonic lethality, cellular growth defects, increased apoptosis, premature aging and/or tumorigenesis (Gowen et al. 1996; Hakem et al. 1996; Liu et al. 1996; Ludwig et al. 1997, 2001; Shen et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999a, b, 2001; Hohenstein et al. 2001; Bachelier et al. 2003; Cao et al. 2003).

The DDR is essential for the development, maintenance, and normal functioning of the adult central nervous system. H2AX is a member of the mammalian histone H2A family (for review see Redon et al. 2002). H2AX is phosphorylated (γ-H2AX) and relocated to double strand breaks (DSBs) within minutes of genotoxic stress, which suggests that γ-H2AX may play a crucial role in DSB repair (Paull et al. 2000). Indeed, γ-H2AX is the molecular component that recruits various DNA damage repair factors to damage sites including BRCA1 (Paull et al. 2000; Celeste et al. 2002; Tauchi et al. 2002; Stucki et al. 2008). Despite the fact that interactions between BRCA1 and γ-H2AX are important in the DNA repair process, the mechanism of interaction of these two molecules has not been thoroughly investigated in neurodegenerative conditions such as HD.

The aim of our study was to address how BRCA1 and H2AX interact and contribute to the DDR in HD. We found that the imbalance of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated level of BRCA1 leads to dysregulation of the spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX, which, in turn, results in failure of the DNA damage response in HD.

RESULTS

The level of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated ATM and BRCA1 are altered in a cellular and animal model of HD

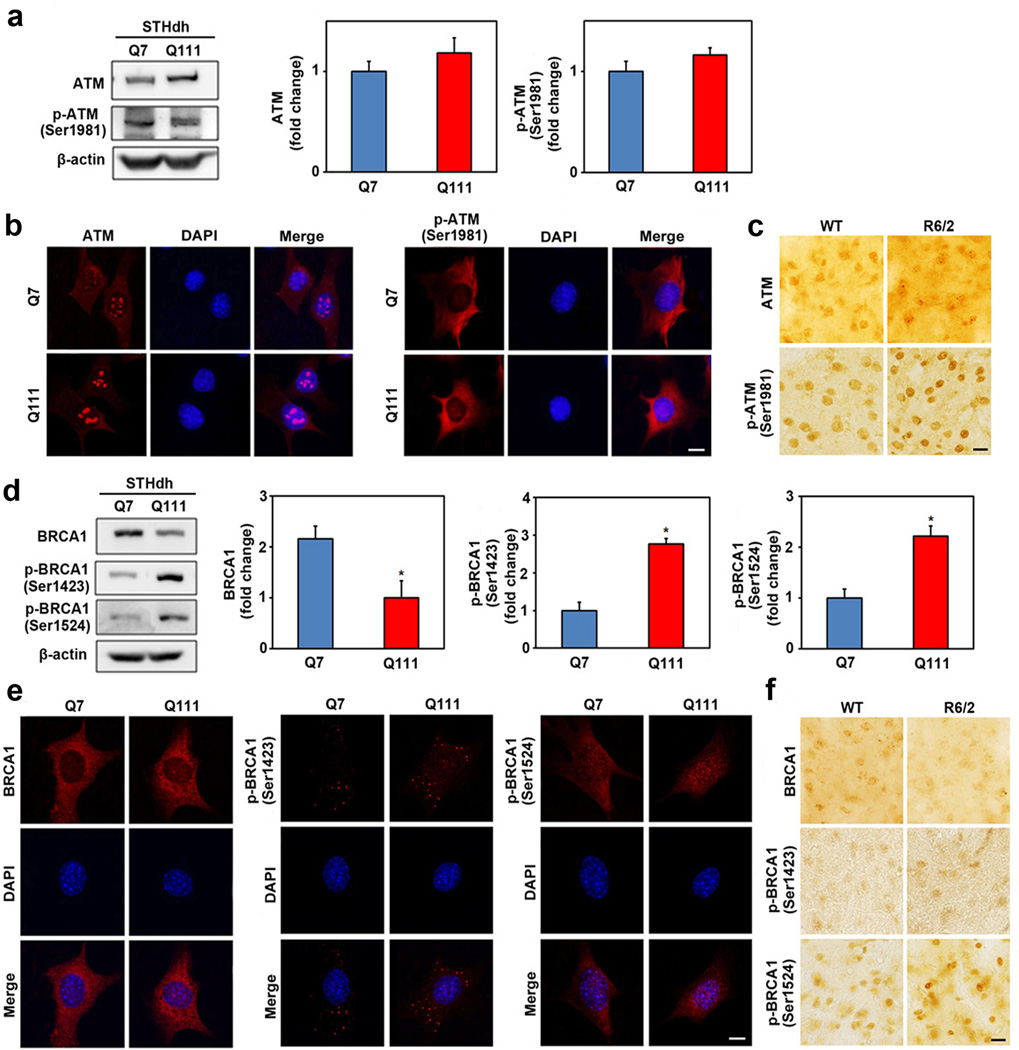

In the first series of experiments, we determined whether levels of ATM and BRCA1 differ between control STHdh Q7/7 (Q7) and mutant HD STHdh Q111/111 (Q111) cells by Western blot and immunohistochemistry. Levels of non-phosphorylated ATM and phosphorylated ATM (p-ATM (Ser1981)) were slightly but not significantly increased in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells (Fig. 1a). ATM and p-ATM (Ser1981) signals were found both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of striatal cell lines. However, a substantial portion of ATM signal appeared to be localized to the nucleus of striatal cells, whereas p-ATM (Ser1981) was localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1b). The R6/2 line is a transgenic HD mouse line expressing exon 1 of the mutant human HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat [30] that develops neuropathological and clinical features similar to human HD including striatal atrophy and neuronal intranuclear inclusions. The levels of ATM and p-ATM (Ser1981) were slightly increased in the striatum of R6/2 mice at 10 weeks of age compared to littermate controls, as monitored by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, levels of non-phosphorylated BRCA1 were significantly decreased in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells whereas phosphorylated BRCA1 (p-BRCA1 (Ser 1423 and Ser 1524) was significantly increased in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells (Fig. 1d). BRCA1 and p-BRCA1 (Ser1423) were localized to the cytoplasm of striatal cells, whereas p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) was mainly localized in the nucleus (Fig. 1e). p-BRCA1 immunoreactivity was increased while non-phosphorylated BRCA1 immunoreactivity was decreased in the striatum of R6/2 mice compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1f). To determine whether BRCA1 was affected in vivo, we examined ATM, BRCA1, p-BRCA1 (Ser1524), and γ-H2AX protein levels in striatal neurons stably expressing GFP or the mutant huntingtin GFP-fusion protein (GFP-Q79) and found that these protein levels were similar to that a cellular and animal model of HD (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated ATM and BRCA1 are altered in cellular and animal model of HD. a, Immunoblot assay for ATM, p-ATM (Ser1981) and β-actin in Q7 and Q111 cells. The data represent an average of four independent experiments. b, Cellular localization of ATM and p-ATM (Ser1981) were found both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of striatal cell lines. c, ATM and p-ATM (Ser1981) levels were slightly increased in the striatum of R6/2 mice at 10 weeks of age compared to littermate controls. d, Immunoblot assay for BRCA-1, p-BRCA1 (Ser1423), p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and β-actin in Q7 and Q111 cells. The data represent an average of four independent experiments. * Significantly different from control at p < 0.05. e, BRCA1 and p-BRCA1 (Ser1423) are localized in the cytoplasm of striatal cells, whereas p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) is localized in the nucleus of striatal cells. f, Phosphorylated forms of BRCA1 levels mice were increased in the striatum of R6/2 mice compared to littermate controls while non-phosphorylated BRCA1 level was lower in the striatum of R6/2 mice. Scale bars: b, c, e, f, 10µm.

CPT-induced DNA damage alters the expression of ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX pathway in a cellular model of HD

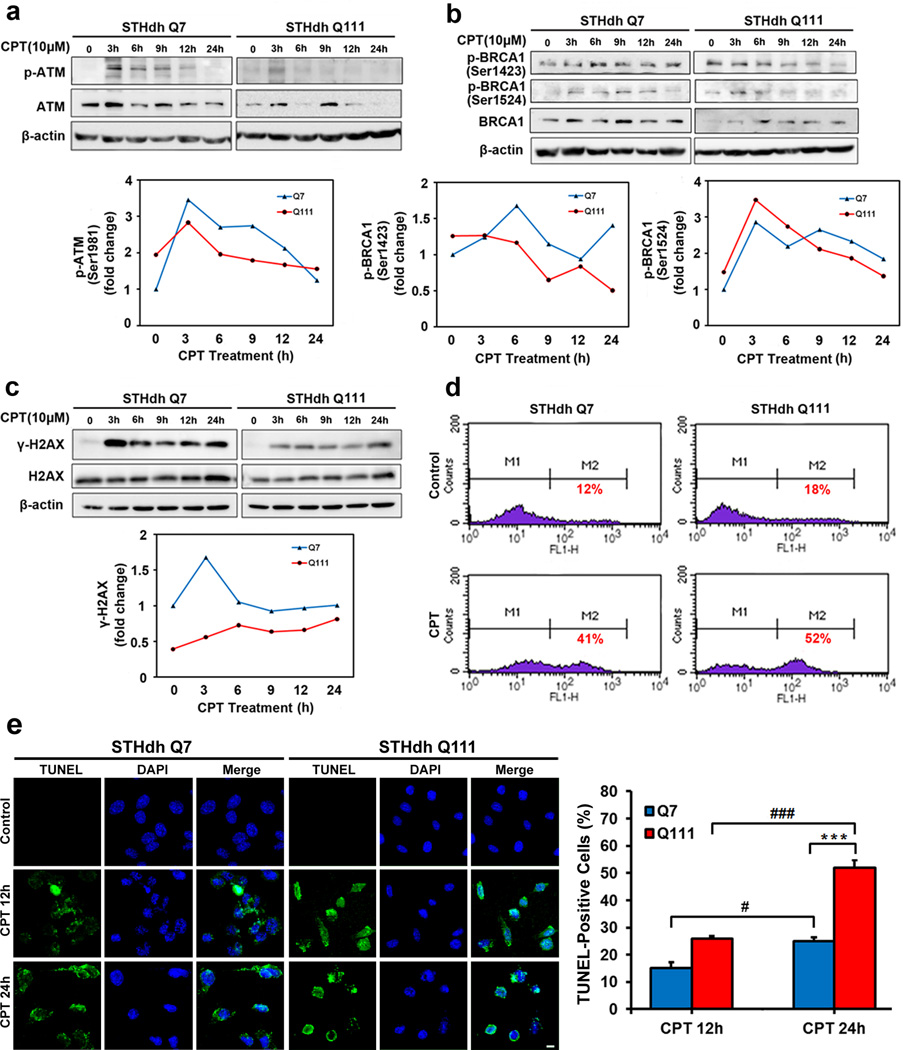

In order to examine whether altered BRCA1 levels affect the DNA damage pathway, we exposed striatal cell lines to camptothecin (CPT), a topoisomerase inhibitor, up to 10 µM for 24 h and investigated the changes in DNA damage responses. Upon CPT-induced DNA damage, we determined the activation of ATM by assessing ATM (ser1981) phosphorylation with Western blot analysis (Fig. 2a). ATM phosphorylation was significantly increased 3 h after the induction of DNA damage and BRCA1 phosphorylation at Ser 1423 and 1524 was increased 3~6 h after the DNA damage(Fig. 2b). These data show that the ATM and BRCA1 pathway is impaired in an HD cell line in response to DNA damage. We next evaluated whether the downstream targets of ATM, such as H2AX, are dysregulated in the context of DNA damage. Phosphorylated H2AX on Ser140 (γ-H2AX) is a sensitive indicator of DNA double-strand breaks produced by genotoxic stresses. Western blot experiments showed that CPT-induced DNA damage response as measured by γ-H2AX levels is evident at 3 h and increased up to 6 h (Fig. 2c). To further determine whether CPT-induced DNA damage is associated with cell death, Q7 and Q111 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS) and TUNEL staining. As shown in the Fig. 2d, CPT (10µM) treatment causes apoptotic cell death both in Q7 and Q111 cells. As expected, there was an increase in apoptotic cell death from 12% to 41% in Q7 control cells and from 18% to 52% in Q111 HD cells, respectively. Also, apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining. HD cells were more sensitive to apoptotic cell death caused by DNA damage (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Activation of ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX pathway by CPT-induced DNA damage is differentially regulated in cellular model of HD. a, Phosphorylation of ATM is reduced in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells. Striatal cells were treated with CPT for the indicated time. Cells were collected and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. b, Phosphorylations of BRCA1 at Ser1423 and S1524 are differentially regulated in between Q7 and Q111 cells. c, Phosphorylations of H2AX at Ser140 is deregulated in Q111 cells. a-c, The data represent an average of three independent experiments. d, CPT-induced DNA damage leads apoptotic cell death in Q7 and Q111 cells as measured by flow cytometric analysis and TUNEL assay. HD cells were more sensitive to apoptotic cell death caused by DNA damage. Typical apoptotic morphology of cytoplasm and nuclei of Q7 and Q111 cells treated with CPT for 12h or 24h. In situ apoptosis detection is represented by green labeling of cytoplasm and nuclei, compared with DAPI (blue) for visualization of all nuclei. Scale bars: 10µm. The TUNEL+ cells in each field were examined with an Olympus epifluorescence microscope at ×20 magnification. The data represent an average of four independent areas. #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001.

Differential subcellular localization of ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX are found in a cellular model of HD

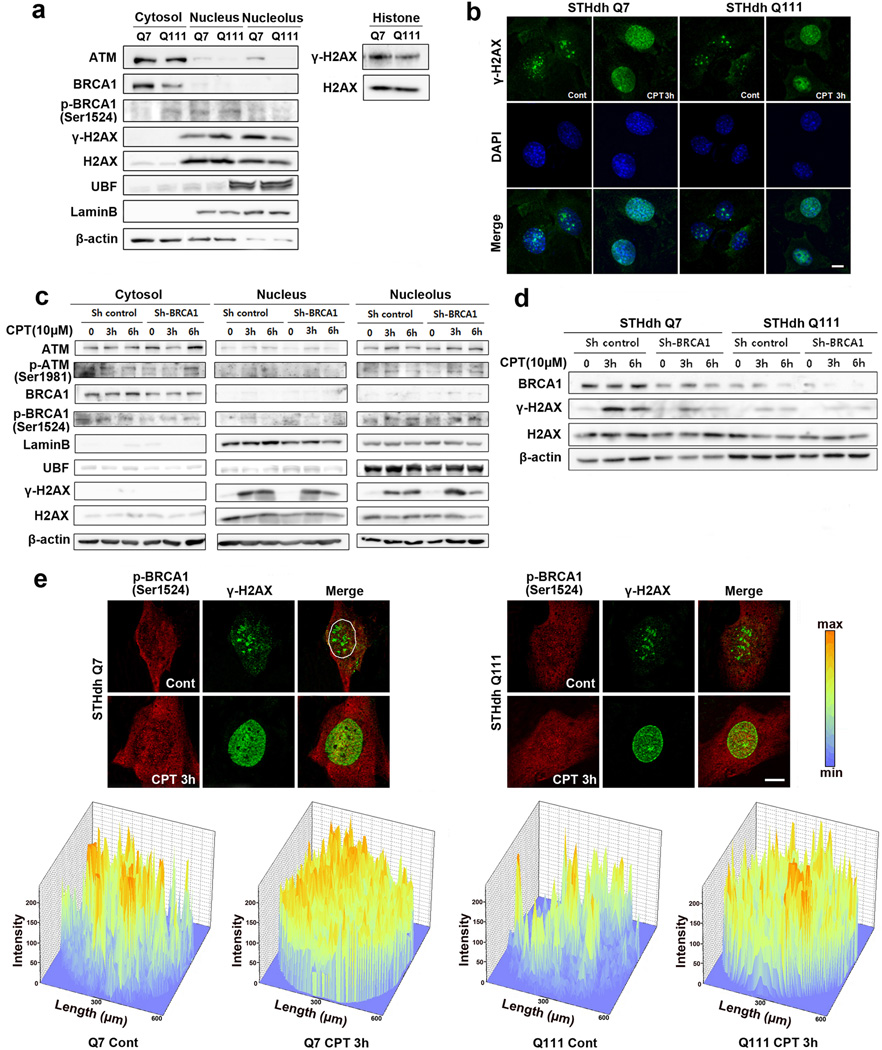

Because subcellular localization is an important factor related to protein function, we investigated the distribution of ATM, BRCA1, and γ-H2AX. Interestingly, ATM and BRCA1 were found both in the nucleus and cytosol of striatal cell lines (STHdh Q7/7 and Q111/111cells). High levels of γ-H2AX protein were found in nucleoli and the basal level was higher in Q7 cells than Q111 cells (Fig. 3a). γ-H2AX immunoreactivity was redistributed in the nuclei of Q7 and Q111 cells at an early stage (3 h) in response to DNA damage. The appearance of nuclear γ-H2AX foci were associated with DNA damage was clearly abnormal in Q111/111 HD cells. This finding is consistent with confocal microscopy data on CPT-induced γ-H2AX foci and DNA DSBs that are prolonged in HD cells but not in normal cells (Fig. 3b). Knock-down of BRCA1 by expressing of EGFP-shRNA BRCA1 constructs inhibited the spatial redistribution of γ-H2AX in the nucleus after CPT treatment. It is noteworthy that γ-H2AX was mainly localized in the nucleolus 3 h after CPT treatment and that levels of γ-H2AX protein in nucleoli were increased in Q7 cells compared to Q111 cells (Fig. 3c). Consistent with the immunofluorescence staining data, BRCA1 knockdown resulted in a marked attenuation of the γ-H2AX activation by CPT in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells (Fig. 3d). Indeed, the appearance of the nuclear γ-H2AX foci that arise and persist longest after DNA damage was impaired in Q111 HD cells. The depletion of BRCA1 depletion coupled to reduced γ-H2AX foci produced by CPT treatment strongly supports a role of BRCA1 in the maintenance of DDR via γ-H2AX. p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and γ-H2AX were also differently localized in Q7 and Q111 cells. Confocal microscopy revealed immunoreactivity of p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and γ-H2AX in the nucleoplasm foci upon CPT treatment. Quantitative analysis of the p-BRCA1(Ser1524) signal in the nucleus of CPT treated cells, revealed that p-BRCA1(Ser1524) distribution is strongly associated with γ-H2AX signal in Q7 cells, whereas p-BRCA1(Ser1524) is partially associated with γ-H2AX in Q111 cells (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Differential subcellular localizations of ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX are found in cellular model of HD. a, The level of γ-H2AX was lower in the nucleoli of Q111 cells but there was no change in a total level of H2AX compared to Q7 cells. b, CPT-induced DNA damage induced spatiotemporal changes of γ-H2AX foci in the nucleus of Q7 and Q111 cells 3h after CPT treatment. c, Knock-down of BRCA1 by shRNA altered the activation and the subcellular localization of γ-H2AX. CPT (10 µM) was treated for 3h. d, Knock-down of BRCA1 resulted in a marked attenuation of the γ-H2AX activation by CPT in Q111 cells compared to Q7 cells. e, Levels of p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and γ-H2AX in the nucleoplasm were differentially regulated in Q7 and Q111 cells after CPT treatment. Upper panel: confocal microscopic images, lower panel: intensity analysis for the images from upper panel. Scale bars: b,e, 10µm.

CPT-induced interaction of BRCA1 and γ-H2AX is impaired in a cellular model of HD

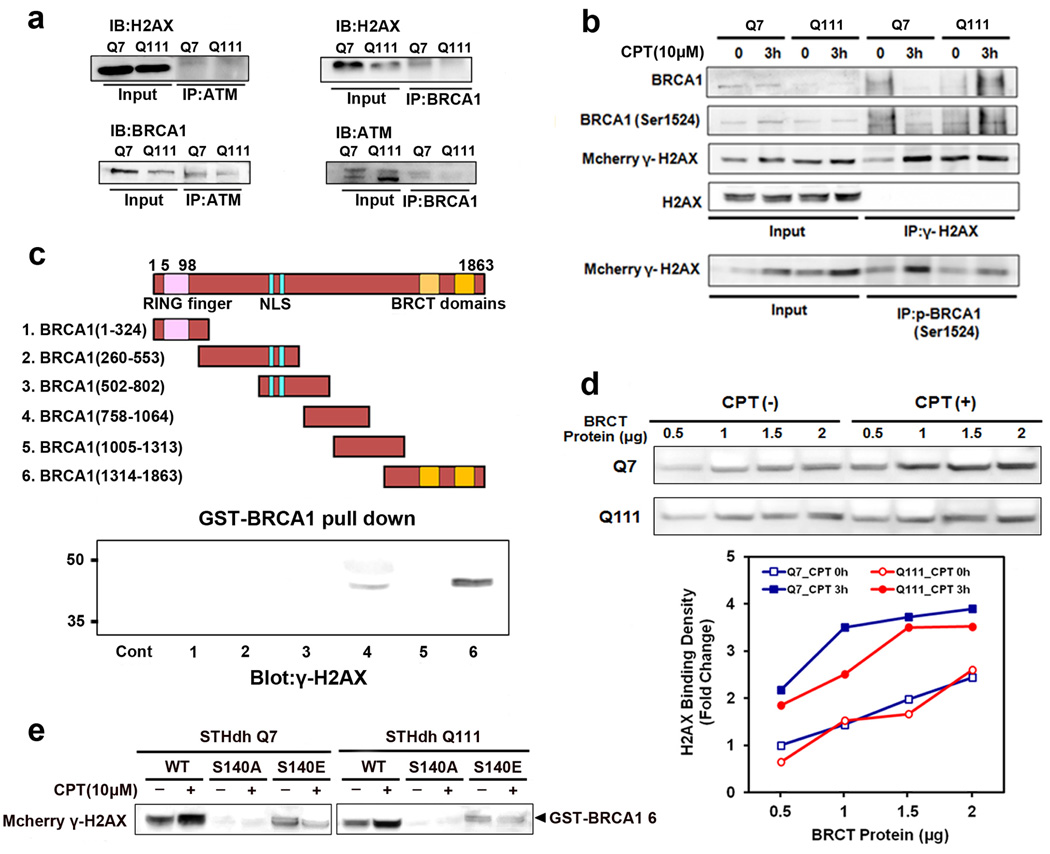

To further characterize the molecular interaction of ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX, we performed immunoprecipitations (IPs) on neuronal lysates, using anti-ATM, anti-BRCA1 or anti-H2AX antibodies (Fig. 4a). A prominent 17kDa band of H2AX protein was present in ATM and BRCA1 IPs. The molecular interaction of H2AX and ATM or BRCA1 was apparent in both Q7 and Q111 cells. We also confirmed that ATM, BRCA1 and H2AX interact constitutively to generate a DDR complex in neurons (Fig. 4a). In order to examine whether DNA damage modulates the association of γ-H2AX with p-BRCA1 (Ser1524), we prepared cell lysates from mcherry-H2AX transfected Q7 and Q111 cells after CPT treatment and performed co-immunoprecipitations. The constitutive association of γ-H2AX with p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) was found in Q7 cells but not in Q111 cells under normal condition without CPT treatment. An increase in the association of γ-H2AX with p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) appeared in Q111 cells 3h after CPT treatment. The strongest association of p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) with γ-H2AX was found in Q7 cells than in Q111 cells after CPT treatment (Fig. 4b). To determine whether γ-H2AX directly binds with BRCA1, six glutathione S-transferase (GST)-BRCA1 fusion proteins (numbered 1–6) containing overlapping BRCA1 fragments were purified and the GST-pull down assay was performed with cell lysates with or without CPT treatment. Among six GST- BRCA1 fusion proteins, γ-H2AX most strongly interacted with the BRCT domains of BRCA1 (BRCA1 amino-acids 1314–1863) (Fig. 4c). Moreover, CPT treatment increased the ability of γ-H2AX binding to BRCT domains of BRCA1 in a BRCT protein concentration-dependent manner in Q7 and Q111 cells (Fig. 4d). The association of γ-H2AX with BRCT domain was more enhanced in Q7 cells than in Q111 cells upon CPT treatment. This data indicates that HD Q111 cells is lacking in the association of γ-H2AX with BRCA1. We further performed GST-BRCA1 pull down using cell lysates containing WT-H2AX, mutant H2AX (S140A), and mutant H2AX (S140E) respectively. Mutation of H2AX at Ser140 hindered the association with BRCA1, indicating that phosphoryation of Ser140 is important for molecular interaction with BRCA1 protein (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

CPT-induced interaction of BRCA1 and γ-H2AX is impaired in cellular model of HD. a, Molecular interaction of H2AX with ATM and BRCA1 were apparent in both Q7 and Q111 cells. b, The binding of γ-H2AX with p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) is increased upon DNA damage by CPT. Mcherry-H2AX was transfected to Q7 and Q111 cells. Cell lysates were prepared 3h after CPT treatment to performe co-immunoprecipitations. c, γ-H2AX interacts with the BRCT domain of BRCA1. GST-BRCA1 pull down assay was performed with cell lysates. d, Binding of H2AX to the BRCT domain is decreased in Q111 HD cells compared to Q7 cells. The data represent an average of three independent experiments. e, The phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser140 is critical for binding to the BRCT domain. GST-BRCA1 pull down assay was performed with cell lysates from Mcherry-H2AX transfected cells.

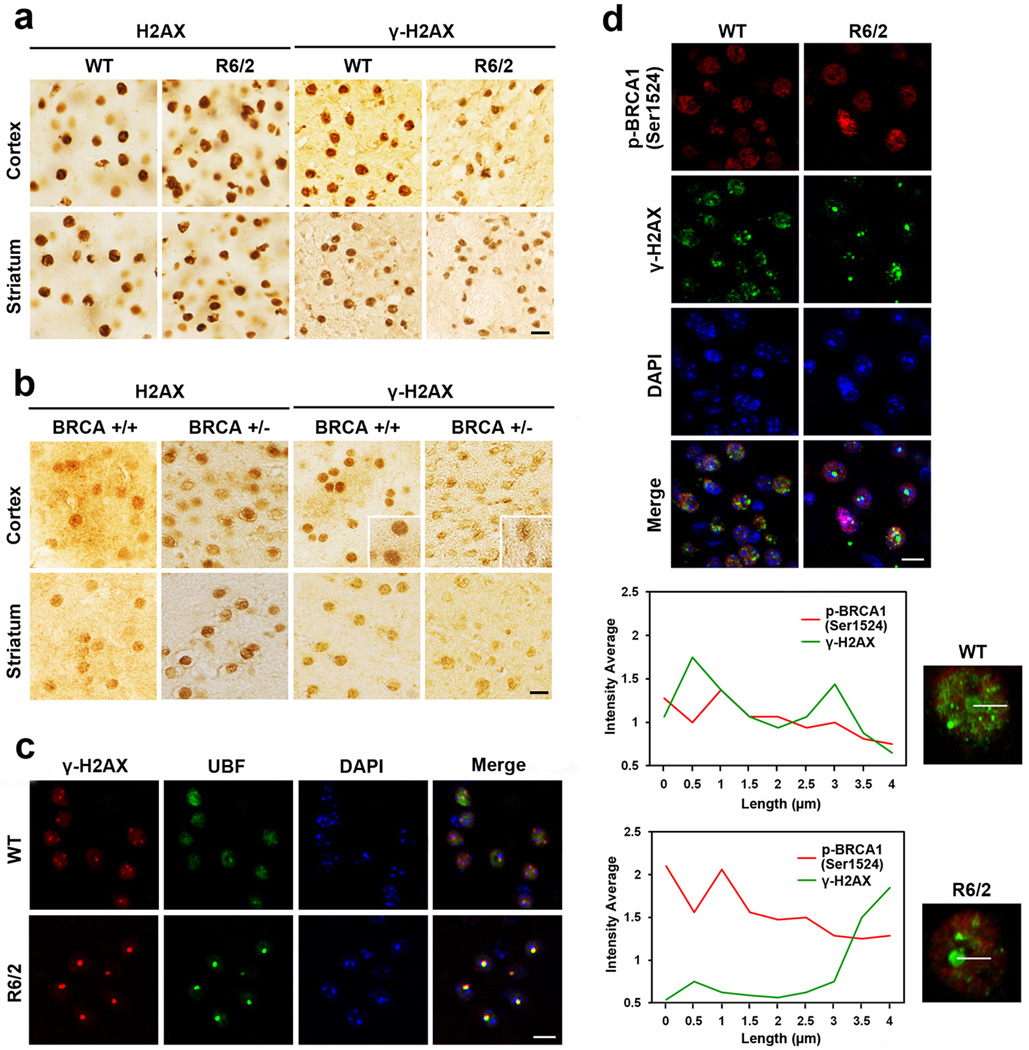

Spatial distribution of γ-H2AX in the nucleus is dysregulated in HD

To determine whether γ-H2AX levels and its spatial distribution in the nucleus are affected in vivo, we examined the immunoreactivity of γ-H2AX in the striatum of R6/2 transgenic mouse model. The levels of γ-H2AX were markedly decreased in the cortex and striatum of R6/2 mice (10 weeks old) compared to littermate controls (Fig. 5a). γ-H2AX was mainly present in the nucleoli that are positively stained with UBF, a well-known nucleolus marker. The bulk and punctate immunoreactivity of γ-H2AX was colocalized with UBF in nucleolar regions (Fig. 5c). The immunoreactivity of p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) is markedly increased in striatal neurons of R6/2 mice in comparison with wild type littermate control mice at 10 weeks of age. p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and mtHtt are not co-localized (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, γ-H2AX immunoreactivity was decreased in the cortex and striatum of BRCA1 hetero knockout (BRCA1+/−) mice compared to WT control (BRCA1+/+) mice, similar to the pattern we found in R6/2 HD mice (Fig. 5b). Confocal microscopic analysis revealed that p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) and γ-H2AX were colocalized in striatal neurons of WT mice. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity confirmed that the γ-H2AX signal was spatially colocalized with p-BRCA1 (Ser1524) signal in the nucleus of striatal neurons of littermate control mice, whereas γ-H2AX was not colocalized with p-BRCA1(Ser1524) in striatal neurons of R6/2 mice (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

The levels of pBRCA1 (Ser 1524) and γ-H2AX are altered in HD mice and BRCA+/− mice. a, γ-H2AX levels were decreased in the cortex and striatum of R6/2 mice compared to control mice. b, γ-H2AX immunoreactivity was decreased in the cortex and striatum of BRCA1 heterozygous knockout (BRCA+/−) mice compared to WT (BRCA+/+) mice. c, γ-H2AX and UBF were colocalized in striatal neurons of WT and R6/2 mice. d, Confocal microscopic analyses revealed that the colocalization of pBRCA1 (Ser1524) and γ-H2AX was differentially regulated in the nucleus of WT and R6/2 mice. Scale bars: a–d, 10µm.

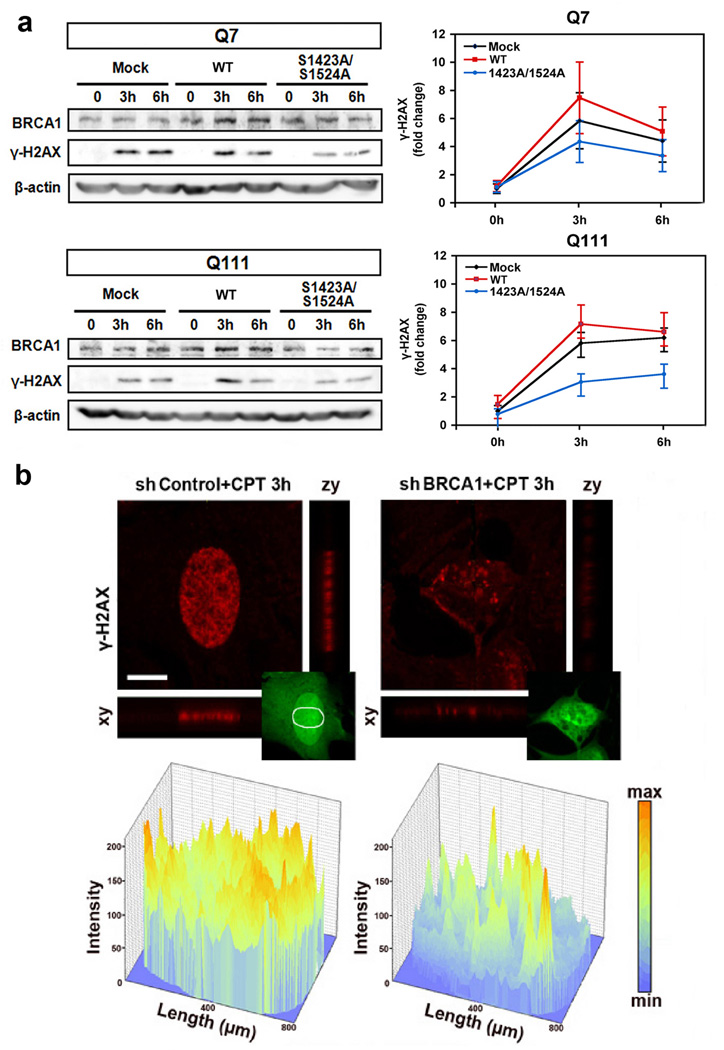

BRCA1 directly regulates the spatiotemporal propagation of γ-H2AX to the nucleoplasm

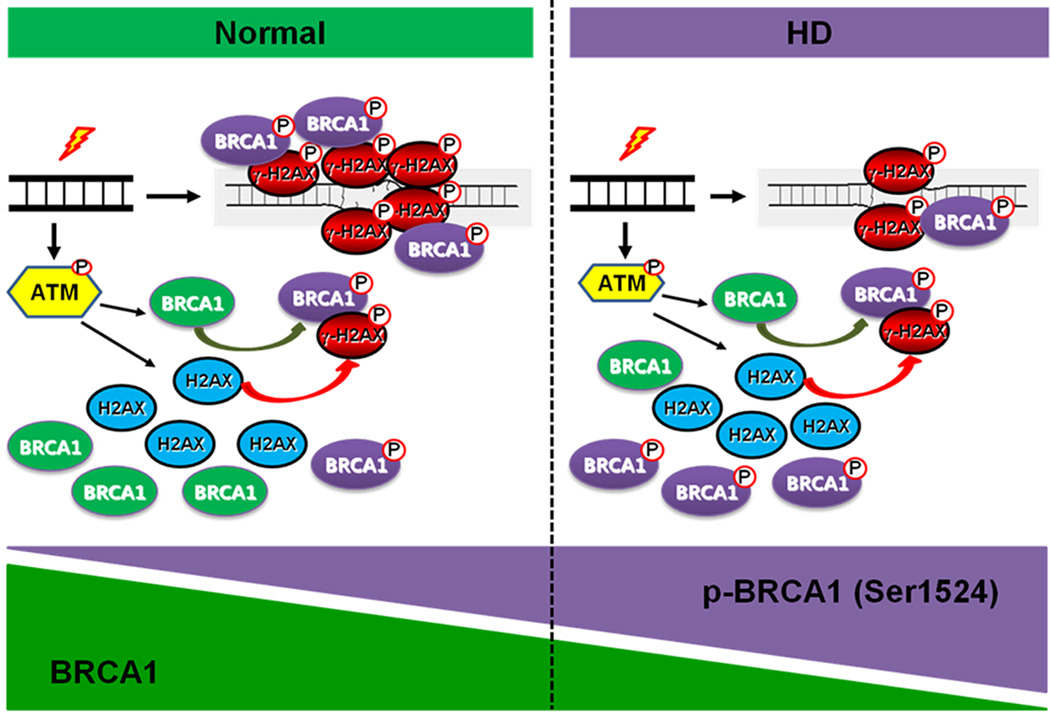

Since we found that BRCA1 directly interacts with γ-H2AX through the BRCT domain, we hypothesized that BRCA1 directly regulates the spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX in response to DNA damage. First, we overexpressed WT-BRCA1 in HD cells (Q111) and found that BRCA1 restores the level of γ-H2AX in response to CPT-induced DNA damage response in Q111 cells as well as in Q7 cells. The phosphorylation site mutant BRCA1 (Ser 1423/1524A) did not restore the level of γ-H2AX under DNA damage response (Fig. 6a). Next, we knocked down BRCA1 using shRNA BRCA1 and observed the propagation of γ-H2AX to the nucleoplasm to verify whether BRCA1 modulates the spatiotemporal dynamic of γ-H2AX or not. Confocal microscopy confirmed that CPT treated BRCA1 knock-down (GFP-positive cells) exhibits an abnormal γ-H2AX spatiotemporal dynamic compared to shRNA-transfected control cells (Fig. 6b). BRCA1 deficiency failed to generate diffused discrete foci of γ-H2AX in response to DNA damage (Fig. 6b). Based on these data, we propose a scheme that summarizes our major findings, i.e., that the phosphorylation status of BRCA1 is imbalanced in normal versus HD striatal cells and that BRCA1-dependent spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX is impaired in HD cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

BRCA1 modulates the spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX and DNA damage response. a, WT-BRCA1 (WT) expression improves the dynamic response of γ-H2AX in response to DNA damage in HD cells. Cells were transfected with either WT or mutant BRCA1 (S1423/S1524A) for 48h and then treated with CPT (10 µM) for the indicated period of time. The data represent an average of three independent experiments. b, Knock-down of BRCA1 reduced the spatiotemporal distribution of γ-H2AX in the nucleus. Cells were transfected with shControl and shBRCA1and exposed to DNA damage by CPT. Upper panel: confocal microscopic images, lower panel: intensity analysis for the images from upper panel. Scale bar: 10µm.

Fig. 7.

A proposed scheme for BRCA1 and γ-H2AX-dependent DNA repair in neurons under normal conditions and in HD. The phosphorylation status of BRCA1 is imbalanced in normal versus HD striatal cells and the BRCA1-dependent spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX is impaired in HD cells. Consequently, BRCA1and γ-H2AX-dependent DNA repair pathway is dysfunctional and DNA damage is exacerbated in HD cells.

DISCUSSION

The neuronal DNA damage response is a key element contributing to the pathogenesis of polyQ diseases such as HD but how it does so is not clear (Giuliano et al. 2003; llluzzi et al. 2009). Understanding the multiple pathogenic pathways and target molecules that underlie DNA repair may lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches to HD. In this study, we present two main findings: 1) the phosphorylation status of BRCA1 is imbalanced in HD striatal cells, 2) BRCA1-dependent spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX is impaired in HD cells, and, as a result, BRCA1-γ-H2AX associated DNA repair is dysfunctional and DNA damage is enhanced in HD cells under genotoxic stress.

BRCA1 phosphorylation is altered in HD

The spatial association of BRCA1 to sites of DNA damage implies that it plays a role in DNA repair. Early stages in the cellular response to DNA damage is accompanied by the phosphorylation of BRCA1 at Ser1423 and Ser1524 by ATM kinase (Gatei et al. 2000, 2001). The phosphorylation of Ser1423 and Ser1524 is thought to plays a key role in DNA damage response because mutated BRCA1 protein lacking these two phosphorylation sites fails to prevent DNA damage. It is unclear how BRCA1 orchestrates this complex cascade of DNA damage response. Upon DNA damage, BRCA1 is dispersed from the discrete foci and relocalized to DNA damage-induced foci. BRCA1 colocalizes in these damage-induced foci with a number of proteins involved in the DNA damage response such as ATM and H2AX (Scully et al. 1997). The phosphorylated histone H2AX (γ-H2AX) significantly overlaps with BRCA1 following DNA damage and the BRCA1-γ-H2AX foci are thought to be sites of DNA repair (Paull et al. 2000). BRCA1 relocalization to damage-induced foci coincides with its phosphorylation (Scully et al. 1997). Importantly, BRCA1 phosphorylation is regarded as an upstream of the signaling cascade first elicited by ATM which in turn leads to then damage-induced downstream events (Foray et al. 2003). In the present study, we found that the ratio of phosphorylated BRCA1 (p-BRCA1 Ser1423 and Ser1524) is elevated and that increased p-BRCA1 level is a marker of the DNA damage response and DNA repair dysfunction in mutant Htt (Q111) cells and in a mouse model of HD. ATM may be essential for regulating the intracellular localization of BRCA1 in HD cells. Of note, the phosphorylation of both ATM and BRCA1 in response to DNA damage was reduced in HD cells compared to controls.

The BRCA1-dependent spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX is impaired in HD

H2AX and its phosphorylated form, γ-H2AX, are fundamental chromatin components involved in DNA repair. Despite many studies investigating γ-H2AX foci in relation to DNA damage, little is known about γ-H2AX foci in normal cells in the absence of DNA damage. Our immunostaining method using detergent treatment enabled us to detect discrete and punctuate γ-H2AX immunoreactivity with typically prominent nucleolar accumulations in both control and HD cells. We found that the γ-H2AX immunoreactivity is constitutively present in the absence of DNA damage response. Consistent with this result, subcelluar fractionation and Western analysis confirmed that both H2AX and γ-H2AX are localized in the nucleolus as well as in the nucleus. Interestingly, upon CPT-induced DNA damage, γ-H2AX relocalized from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm where sites of DNA repair exist. This new finding suggests that γ-H2AX may be involved in the maintenance of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) under normal condition and that it can be redistributed and translocalized to the sites of DNA DSB (double stranded breaks) when the DNA damage occurs in the nucleus.

DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of BRCA1 modulates its physical association with other components to facilitate DNA repair processes (Foray et al. 2003). In this study, we provide direct evidence that BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) repeat domain interacts with both H2AX and γ-H2AX. The in vitro GST-pull down assay and in vivo immunoprecipitation confirm that the BRCT domain of BRCA1 recognizes γ-H2AX. In case of HD (Q111) cells, we found that the diffused distribution of γ-H2AX is delayed or dysfunctional at the early stage of DNA damage response. In these cells, the delayed phosphorylation of BRCA1 and the diffused distribution of p-BRCA1 were apparent. These findings are consistent with the biochemical evidence for CPT-induced foci pattern of γ-H2AX and p-BRCA1 that is prolonged in HD cells but not in normal cells. In addition, knock-down of BRCA1 by shRNA impaired its function in nonhomologous end joining via γ-H2AX, which consequently increases TUNEL-positive DSB accumulation. Given that one of the earliest molecular responses to DNA DSB is the recruitment of γ-H2AX to sites of DNA damage, the decreased spatiotemporal dynamics of γ-H2AX due to BRCA1 deficiency suggests that, BRCA1 is indeed a critical factor necessary for the assembly the DNA repair complex that acts by distributing γ-H2AX. It seems likely that the arrival of BRCA1 and γ-H2AX to sites of DNA damage is precisely regulated to initiate the repair of damaged DNA under normal conditions. In contrast, cells with a deficiency of BRCA1 or an imbalance of BRCA1/p-BRCA1 manifest delayed timing of spatiotemporal γ-H2AX that leads to exacerbated DNA damage-induced DSB accumulation in a model of HD, suggesting that BRCA1 contributes to DNA damage through γ-H2AX-depdendent pathway in HD (Fig. 7). This slow activation of DNA damage response may lead to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration in HD (llluzzi et al. 2009). Which DSB repair pathway, a non-homologous end joining or a homology-directed repair, is dominated by BRCA1 in neurodegenerative conditions, remains to be determined.

In conclusion, our data validate that the level of p-BRCA1 and γ-H2AX are makers of DNA damage response in HD. The deficiency of BRCA1impairs the spatiotemporal distribution of γ-H2AX and leads to neuronal damage in HD under DNA damage. Our findings suggest that modulation of BRCA1 may improve the DNA damage response and ameliorate the progression of HD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs

The S140A and S140E mutations in Mcherry-C1-H2AX Vector were created by using the KOD-Plus-Mutagenesis Kit (TOYOBO, Japan). The mutations were verified by sequencing.

GST Pull-down Assay

GST pull-down assay using cell lysates of H2AX transfected Q7 and Q111 cells were performed (Ouchi et al. 2004).

Cell Culture and DNA damage

STHdhQ7/7 (wild type) and STHdhQ111/111 (HD knock-in striatal cell line expresses mutant huntingtin at endogenous level), were generously provided from Dr. Marcy MacDonald (Harvard Medical School) (Trettel et al. 2000). Cells were treated at the indicated amount of time with camptothecin (CPT; 10 µM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

RNA interference experiment

Four shRNA-BRCA1 expression plasmids were constructed in pRS under U6 promoter control using the following target sequence in each of the vector: 1. 5’-AAATGCCAGTCAGGCACAGCAGAAACCTA-3’, 2. 5’-TGGCACTCAGGAAAGTATCTCGTTACTGG-3’, 3. 5’-AAGGAACCTGTCTCCACAAAGTGTGACCA-3’, 4. 5’-AGGACCTGCGAAATCCAGAACAAAGCACA-3’. These vectors were constructed by and purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). Cells were seeded and allowed to attach for 24 hr before transfection with either shRNA-BRCA1 or control shRNA by using the transfection reagent supplied by the manufacturer and according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Lipofectamine™ LTX and PLUS Reagents, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Frederick, MD) for 48h.

Animals

The male R6/2 mice were bred with females from their background strain (B6CBAFI/J), and offspring were genotyped using PCR (Mangiarini et al. 1996; Ryu et al. 2003, 2006). CAG repeat length remained stable within a 147–153 range. Female mice were used in the experimental paradigms. BRCA1 heterozygous knockout (BRCA+/−) and wild-type (BRCA+/+) mice were generously provided from Dr. Lee (Liu et al. 1996).

Subcellular Fraction

Cell pellet was washed with PBS and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 4min at 4°C. Pellet was resuspended in 500 µl of ice-cold Buffer (10mM HEPES-KOH, pH7.9, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10mM KCL, 0.5mM DTT and protease inhibitors), kept on ice for 5 min and dounce homogenized twenty times using a tight pestle. Dounced pellets were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5min at 4°C to pellet nuclei and other fragments. The supernatant can be retained as the cytoplasmic fraction. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 300 µl 0.25M sucrose, 10mM MgCl2 and layered over 300 µl 0.35M sucrose, 0.5mM MgCl2 and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5min at 4°C. This step results in a cleaner nuclear pellet. The clean, pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 300 µl 0.35M sucrose, 0.5mM MgCl2 and sonicated six times with each time for 10sec using Bioruptor. The sonicated sample was then layered over 300 µl 0.88M sucrose, 0.5mM MgCl2 and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10min at 4°C. The pellet contains the nucleoli and the supernatant can be retained as the nucleoplasmic fraction. The nucleoli was resuspended in 350mM RIPA buffer and centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 10min at 4°C.

Flow Cytometry analysis

Harvested cells were treated with reagent in accordance with the instruction provided by the manufacturer (FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit), and staining cells was analyzed using a FACSort (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Graphs were exported as TIF images and assembled in Photoshop.

Histopathological Evaluation

Brain tissue sections were immunostained for BRCA1, phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1423), phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1524), H2AX, and γ-H2AX using a previously reported conjugated secondary antibody method. Preabsorption with excess target proteins, omission of the primary antibodies, and omission of secondary antibodies were performed to determine the amount of background generated from the detection assay.

Confocal Microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy was used to determine the ATM (Santa Cruz Biotech), p-ATM (Ser1981) (Upstate Biotech), BRCA1 (Santa Cruz Biotech), phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1423) (Santa Cruz Biotech), phospho-BRCA 1 (Santa Cruz Biotech) (Ser1524), H2AX (Santa Cruz Biotech), and γ-H2AX (Upstate Biotech). The specimens were incubated for 1 h with DyLight 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody, DyLight 488 donkey anti-goat IgG antibody and DyLight 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Baltimore Pike, PA, USA; 1:400) after the incubation of primary antibody. Images were analyzed using an Olympus FluoView FV10i confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Control experiments were performed in the absence of primary antibody or in the presence of blocking peptide.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed as previously described (Ryu et al. 2011). A total of 30 µg of protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-ATM, anti-p-ATM (Ser1981), anti-BRCA1, anti-phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1423), anti-phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1524), anti-H2AX, and anti-γ-H2AX antibodies. Protein loading was controlled by probing for β-actin (Santa Cruz Bitotech) on the same membrane. The densitometry analysis of protein intensity was performed by a imaging analyzer (LAS-3000; Fuji, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, and lysates were centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 10 min. Equal amounts of protein were precipitated with ATM, BRCA1, phospho-BRCA1 (Ser1524), and H2AX. The procedures were performed as previously described (Ryu et al. 2011).

TUNEL asssay

To detect CPT-induced apoptosis, we cultured Q7 and Q111 striatal cells on 24-well plates. Cells were treated at the indicated amount of time (12h and 24h) with 10 µM CPT before detection of apoptotic cells using TUNEL staining (ApopTag Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit, CHEMICON International, Inc.). The apoptotic cells in each field were examined with an Olympus epifluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at ×20 magnification.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Prizm software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) using either Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank to Dr. Marcy MacDonald for STHdhQ7/7 and STHdhQ111/111 cells.

REFERENCES

- Bachelier R, Xu X, Wang X, Li W, Naramura M, Gu H, Deng CX. Normal lymphocyte development and thymic lymphoma formation in Brca1 exon-11-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2003;22:528–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Li W, Kim S, Brodie SG, Deng CX. Senescence, aging, and malignant transformation mediated by p53 in mice lacking the Brca1 full-length isoform. Genes Dev. 2003;17:201–213. doi: 10.1101/gad.1050003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeste A, PetersenS, Romanienko PJ, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Sedelnikova OA, Reina-San-Martin B, Coppola V, Meffre E, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Genomic instability in mice lacking histone H2AX. Science. 2002;296:922–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1069398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Farmer AA, Chen CF, Jones DC, Chen PL, Lee WH. BRCA1 is a 220-kDa nuclear phosphoprotein that is expressed and phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppedè F, Migliore L. DNA repair in premature aging disorders and neurodegeneration. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:3–19. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ. Requirement of ATM-dependent phosphorylation of brca1 in the DNA damage response to double-strand breaks. Science. 1999;286:1162–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng CX, Wang RH. Roles of BRCA1 in DNA damage repair: a link between development and cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(Spec No 1):R113–R123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foray N, Marot D, Gabriel A, Randrianarison V, Carr AM, Perricaudet M, Ashworth A, Jeggo P. A subset of ATM- and ATR-dependent phosphorylation events requires the BRCA1 protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:2860–2871. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatei M, Scott SP, Filippovitch I, Soronika N, Lavin MF, Weber B, Khanna KK. Role for ATM in DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of BRCA1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3299–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatei M, Zhou BB, Hobson K, Scott S, Young D, Khanna KK. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase and ATM and Rad3 related kinase mediate phosphorylation of Brca1 at distinct and overlapping sites. In vivo assessment using phospho-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17276–17280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano P, De Cristofaro T, Affaitati A, Pizzulo GM, Feliciello A, Crscuolo C, De Michele G, Filla A, Awedimento EV, Varrone S. DNA damage induced by polyglutamine-expanded proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2301–2309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LC, Johnson BL, Latour AM, Sulik KK, Koller BH. Brca1 deficiency results in early embryonic lethality characterized by neuroepithelial abnormalities. Nat Genet. 1996;12:191–194. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakem R, de la Pompa JL, Sirard C, Mo R, Woo M, Hakem A, Wakeham A, Potter J, Reitmair A, Bilia F, et al. The tumor suppressor gene Brca1 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Cell. 1996;85:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenstein P, Kielman MF, Breukel C, Bennett LM, Wiseman R, Krimpenfort P, Cornelisse C, van Ommen GJ, Devilee P, Fodde R. A targeted mouse Brca1 mutation removing the last BRCT repeat results in apoptosis and embryonic lethality at the headfold stage. Oncogene. 2001;20:2544–2550. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illuzzi J, Yerkes S, Parekh-Olmedo H, Kmiec EB. DNA breakage and induction of DNA damage response proteins precede the appearance of visible mutant huntingtin aggregates. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:733–747. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtun IV, Liu Y, Bjoras M, Klungland A, Wilson SH, McMurray CT. OGG1 initiates age-dependent CAG trinucleotide expansion in somatic cells. Nature. 2007;447:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Collins KM, Brown AL, Lee CH, Chung JH. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;404:201–204. doi: 10.1038/35004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Flesken-Nikitin A, Li S, Zeng Y, Lee WH. Inactivation of the mouse Brca1 gene leads to failure in the morphogenesis of the egg cylinder in early postimplantation development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1835–1843. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungman M, Lane DP. Transcription - guarding the genome by sensing DNA damage. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:727–737. doi: 10.1038/nrc1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig T, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A. Targeted mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene homologs in mice: lethal phenotypes of Brca1, Brca2, Brca1/Brca2, Brca1/p53, and Brca2/p53 nullizygous embryos. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1226–1241. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig T, Fisher P, Ganesan S, Efstratiadis A. Tumorigenesis in mice carrying a truncating Brca1 mutation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1188–1893. doi: 10.1101/gad.879201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, et al. Exon1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi M, Fujiuchi N, Sasai K, Katayama H, Minamishima YA, Ongusaha PP, Deng C, Sen S, Lee SW, Ouchi T. BRCA1 phosphorylation by Aurora-A in the regulation of G2 to M transition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19643–19648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull TT, Rogakou EP, Yamazaki V, Kirchgessner CU, Gellert M, Bonner WM. A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2000;10:886–895. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon C, Pilch D, Rogakou E, Sedelnikova O, Newrock K, Bonner W. Histone H2A variants H2AX and H2AZ. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffner H, Verma IM. BRCA1 is a cell cycle-regulated nuclear phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7138–7143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H, Lee J, Zaman K, Kubilis J, Ferrante RJ, Ross BD, Neve R, Ratan RR. Sp1 and Sp3 are oxidative stress-inducible, anti-death transcription factors in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3597–3606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03597.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H, Lee J, Hagerty SW, Soh BY, MacAlpin SE, Cormier KA, Smith KM, Ferrante RJ. ESET/SETDB1 gene expression and histone H3 (K9) trimethylation in Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19176–19181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606373103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H, Jeon GS, Cashman NR, Kowall NW, Lee J. Differential expression of c-Ret in motor neurons versus non-neuronal cells is linked to the pathogenesis of ALS. Lab Invest. 2011;91:342–352. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully R, Chen J, Ochs RL, Keegan K, Hoekstra M, Feunteun J, Livingston DM. Dynamic changes of BRCA1 subnuclear location and phosphorylation state are initiated by DNA damage. Cell. 1997;90:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully R, Ganesan S, Vlasakova K, Chen J, Socolovsky M, Livingston DM. Genetic analysis of BRCA1 function in a defined tumor cell line. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen SX, Weaver Z, Xu X, Li C, Weinstein M, Chen L, Guan XY, Ried T, Deng CX. A targeted disruption of the murine Brca1 gene causes gamma-irradiation hypersensitivity and genetic instability. Oncogene. 1998;17:3115–3124. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starita LM, Parvin JD. The multiple nuclear functions of BRCA1: transcription, ubiquitination and DNA repair. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M, Clapperton JA, Mohammad D, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ, Jackson SP. MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2008;133:549. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchi H, Kobayashi J, Morishima K, van Gent DC, Shiraishi T, Verkaik NS, van Heems D, Ito E, Nakamura A, Sonoda E, et al. Nbs1 is essential for DNA repair by homologous recombination in higher vertebrate cells. Nature. 2002;420:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trettel F, Rigamonti D, Hilditch-Maguire P, Wheeler VC, Sharp AH, Persichetti F, Cattaneo E, MacDonald ME. Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh (Q111) striatal cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2799–2809. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkitaraman AR. Functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the biological response to DNA damage. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3591–3598. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Weaver Z, Linke SP, Li C, Gotay J, Wang XW, Harris CC, Ried T, Deng CX. Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999a;3:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Wagner KU, Larson D, Weaver Z, Li C, Ried T, Hennighausen L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng CX. Conditional mutation of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells results in blunted ductal morphogenesis and tumour formation. Nat Genet. 1999b;22:37–43. doi: 10.1038/8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Qiao W, Linke SP, Cao L, Li WM, Furth PA, Harris CC, Deng CX. Genetic interactions between tumor suppressors Brca1 and p53 in apoptosis, cell cycle and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:266–271. doi: 10.1038/90108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Sato T, Shimohata T, Hayashi S, Igarashi S, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. Interaction between neuronal intranuclear inclusions and promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear and coiled bodies in CAG repeat diseases. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.