Abstract

In wild-type lenses from various species, an intracellular hydrostatic pressure gradient goes from ∼340 mmHg in central fiber cells to 0 mmHg in surface cells. This gradient drives a center-to-surface flow of intracellular fluid. In lenses in which gap-junction coupling is increased, the central pressure is lower, whereas if gap-junction coupling is reduced, the central pressure is higher but surface pressure is always zero. Recently, we found that surface cell pressure was elevated in PTEN null lenses. This suggested disruption of a feedback control system that normally maintained zero surface cell pressure. Our purpose in this study was to investigate and characterize this feedback control system. We measured intracellular hydrostatic pressures in mouse lenses using a microelectrode/manometer-based system. We found that all feedback went through transport by the Na/K ATPase, which adjusted surface cell osmolarity such that pressure was maintained at zero. We traced the regulation of Na/K ATPase activity back to either TRPV4, which sensed positive pressure and stimulated activity, or TRPV1, which sensed negative pressure and inhibited activity. The inhibitory effect of TRPV1 on Na/K pumps was shown to signal through activation of the PI3K/AKT axis. The stimulatory effect of TRPV4 was shown in previous studies to go through a different signal transduction path. Thus, there is a local two-legged feedback control system for pressure in lens surface cells. The surface pressure provides a pedestal on which the pressure gradient sits, so surface pressure determines the absolute value of pressure at each radial location. We speculate that the absolute value of intracellular pressure may set the radial gradient in the refractive index, which is essential for visual acuity.

Introduction

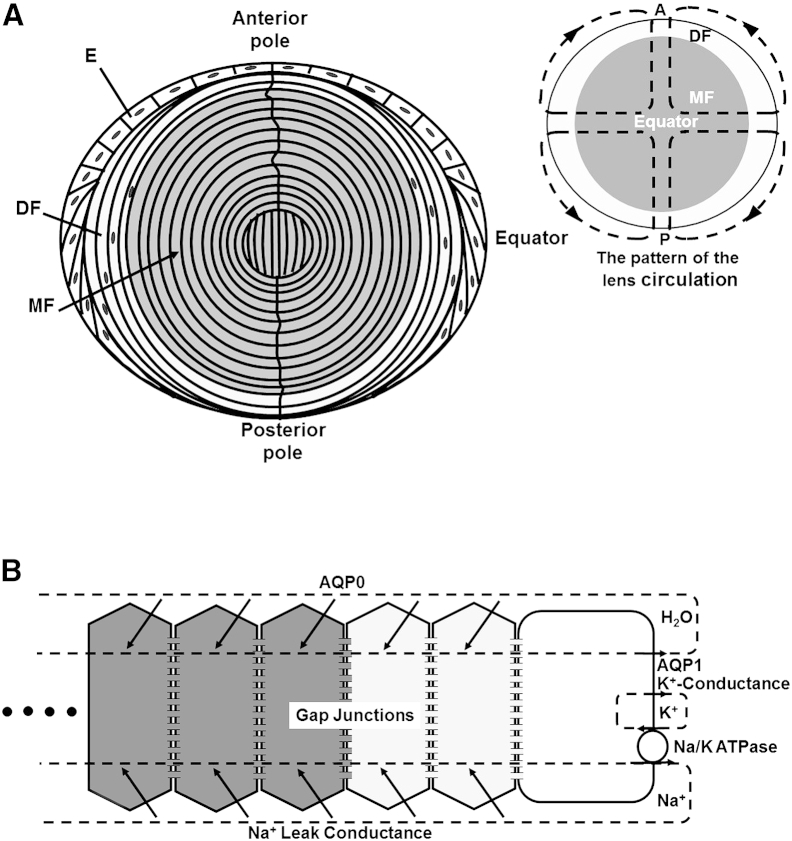

Lenses in most species have similar cellular structures and transport properties, though there are subtle differences in shape and protein expression. A single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells (E in Fig. 1 A) covers the anterior hemisphere. All cell division occurs in the epithelium, mostly at a location about halfway between the anterior pole and equator (reviewed in Griep and Zhang (1)). At the equator, epithelial cells elongate and differentiate into fiber cells that make up the mass of the lens. As new epithelial cells are pushed toward the equator, differentiating cells are internalized to become what we call differentiating fiber cells (DFs; Fig. 1 A). These cells have a different complement of cytoplasmic proteins and membrane transport proteins compared with their epithelial progenitors, but they retain internal organelles, so protein synthesis can continue. At ∼10–15% of the distance into the lens, the DFs go through an abrupt transition to become mature fiber cells (MFs; Fig. 1 A). During the DF-to-MF transition, internal organelles are degraded (2) and most membrane proteins are posttranslationally modified, usually by cleavage of their C-termini (3, 4). The loss of internal organelles is necessary for transparency, as organelles would scatter light, but the consequence is that MFs cannot synthesize new proteins. Thus, MFs must survive for the lifetime of the organism without any protein turnover. Moreover, since blood vessels would also scatter light, the lens is avascular, and MFs must survive this challenge as well.

Figure 1.

Cellular structure and transport properties of the lens. (A) Cellular structure of the lens. The lens comprises three cell types: anterior surface epithelial cells (E), peripheral differentiating fiber cells (DF), and central mature fiber cells (MF). The inset shows dashed lines of flow superimposed on the lens, indicating the pattern of lens circulation of salt and water. (B) Localization of transport properties leading to the internal circulation of salt and water.

The lack of blood flow in the lens is compensated for by an internal circulation of salt and water (reviewed in Mathias et al. (5)). The overall pattern of the circulation is superimposed on the inset of the lens structure shown in Fig. 1 A. This pattern was first demonstrated by Robinson and Paterson (6), who used a vibrating probe to measure current flow just outside of the lens. We subsequently provided evidence that the circulation is driven primarily by Na+ transport (5). Na+ flows into the lens along extracellular spaces between fiber cells. As it flows toward the lens center, it is driven by its transmembrane electrochemical potential to move into the fiber cells (Fig. 1 B). The membrane channels responsible for its transmembrane movement are not definitively known, but a recent study suggested that Cx46 hemichannels contribute to this movement (7). Once Na+ enters the intracellular compartment, it flows back toward the lens surface from cell to cell through the fiber-cell gap junctions made from Cx46 and Cx50 (Fig. 1 B). Intracellular flow is directed to the equator by a concentration of gap-junction coupling conductance in the equatorial DFs (8, 9). The Na+ flux is transported back out of the lens by the epithelial Na/K ATPase, which is concentrated in the equatorial cells (10, 11, 12). Fiber cells have a very low level of Na/K ATPase activity (12), and newly formed DFs at the lens equator may contribute to the Na+ efflux. Thus, not only does the Na/K ATPase complete the circulation of Na+ by transporting it out of equatorial cells, it also maintains the fiber cell transmembrane electrochemical potential for Na+, which drives Na+ entry into fiber cells within the lens.

As Na+ crosses cell membranes, it creates a small osmotic difference, which causes water to follow. The inflow of water along the extracellular spaces within the lens carries nutrients and antioxidants from the aqueous and vitreous humors to the central MFs. Lens fiber cells express glucose transporters (13, 14) that mediate the uptake of these nutrients. Lens fiber cells also express transporters for amino acids involved in the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione (15, 16, 17). The intracellular flow of water from central MFs to the surface carries waste products that can be metabolized and eliminated by surface cells. The angular circulation around the lens ensures that there will be no recirculation of equatorially eliminated waste products with a polar inflow of solution. These properties of the lens fluid circulation make it an obvious candidate as a functional replacement for blood flow in the avascular lens.

Other ion fluxes are also associated with the lens circulation. Data suggest that H+ and Ca2+ circulate in a manner similar to that observed for Na+ (reviewed in Mathias et al. (5); however, the fluxes and concentrations of these ions are too small to significantly affect the overall circulation. K+ is a major biological cation and if it were to circulate, it would move in directions opposite to Na+, thus greatly reducing the net circulation of solute. However, fiber cells have a very low K+ conductance (5) and, as shown in Fig. 1, the Na/K ATPase and most of the lens K+ conductance appear to reside in the epithelium. Hence, potassium passively leaks out of the lens at the same physical location as its active uptake, and there is very little circulation. Model calculations and data suggest that Cl− circulates in a unique pattern owing to spatial changes in transmembrane voltage relative to the Nernst potential for Cl− (5). Cl− conductance in the membrane appears to be comparable to Na+ conductance, but since Cl− is much closer to electrochemical equilibrium, its flux is much smaller than that of Na+. This implies that solute transport by the lens is not electrically neutral; rather, it is nearly equal to Na+ transport. The lens is different from most epithelia in that it transports in the short-circuit condition. Therefore, a sodium ion that leaves the lens at the equator is short circuited by the external solution to the poles, where it reenters the lens, maintaining electroneutrality through circulation of charge rather than a balance of anion and cation fluxes, as is the case with most epithelia, which transport in the open-circuit condition.

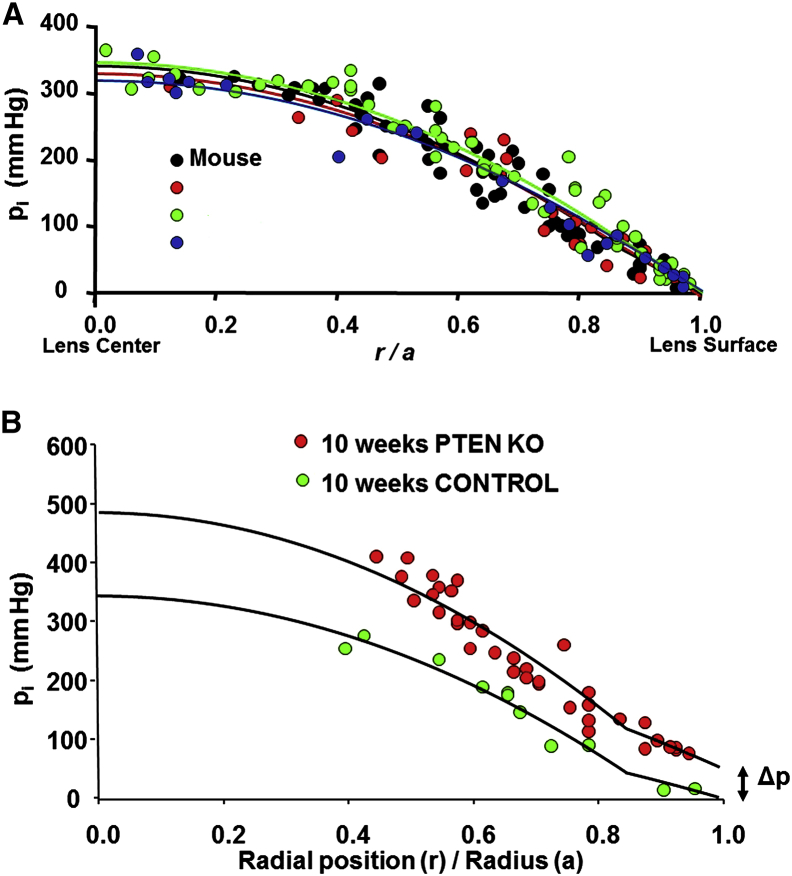

A mathematical model of the circulation, published in 1985, first predicted that water would follow the transport of Na+ (5, 18). This hypothesis was not universally accepted. Lens researchers seemed to accept a circulation of Na+, since a circulating current had been directly measured (6), but some found it difficult to accept that water should follow. In 2010, the fluid-circulation model was challenged in a point-counterpoint pair of articles (19, 20). At that time, evidence supporting fluid flow was indirect and required model calculations to link measurements of spatial variations in salt transport with fluid flow. However, that changed in 2011 when direct evidence of water flow was obtained in three different laboratories. Gao et al. (21) measured intracellular hydrostatic pressure (pi) in wild-type mouse lenses and found a large parabolic gradient, with the intracellular pressure in central fiber cells being ∼340 mmHg and that in surface cells being zero (see Fig. 2). They showed that the pressure in central cells varied inversely with the density of fiber-cell gap junctions and directly with the rate of Na+ transport, but the surface pressure was always zero. Thus, the pressure in central fiber cells could be experimentally altered in a manner consistent with the fluid-circulation model in Fig. 1 B. Vaghefi et al. (22) used magnetic resonance imaging to show that water entered the bovine lens at both poles and then circulated around to exit at the equator. They also showed that the vectorial flow of water ceased when Na+ transport was blocked, which caused the pattern to become random. Lastly, Candia et al. (23) used a modified Ussing chamber to directly measure water inflow at the anterior and posterior surfaces and outflow at the equatorial surface in bovine lenses. Again, the water flow ceased when Na+ transport was blocked. These studies, particularly the work in Candia et al.’s lab, appear to settle the controversy.

Figure 2.

Intracellular hydrostatic pressure (Δp) gradients in different types of lenses. (A) Intracellular pressures in lenses from mice (a = 0.10 cm), rats (a = 0.22 cm), rabbits (a = 0.48 cm), and dogs (a = 0.57 cm). Reproduced from Gao et al. (24) with permission from Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, which holds the copyright. When pressures at each radial location (r) were normalized by the radius (a), the profiles were indistinguishable. (B) Intracellular Δp measured in wild-type and PTEN null mouse lenses at 10 weeks of age. Reproduced from Sellitto et al. (25) with the permission from the Journal of Clinical Investigation, which holds the copyright. In PTEN knockout lenses, intracellular Δp in cells at the surface became progressively more positive with age until the lenses began to rupture at 12 weeks of age. There was also a slight reduction in gap-junction coupling, which caused a small increase in the pressure gradient.

Gao et al. (24) measured intracellular hydrostatic pressures in lenses of different sizes from different species. The expectation was that central pressure would increase dramatically with increasing size, since there would be a larger volume of fluid flowing along a longer path. However, this was not observed. Fig. 2 A shows their remarkable and unexpected result. When the distance from the lens center (r cm) is normalized by the lens radius (a cm), the pressure profiles all appear identical. From this, one can conclude there is something intrinsically important about the absolute value of intracellular pressure: the central pressure needs to be 340 mmHg and the surface pressure must be 0 mmHg. After further investigation, they found that in larger lenses the water flow velocity decreased because Na+ transport decreased. Their data suggested this was probably due to a reduction in the expression of fiber-cell leak conductance channels for Na+. Gap-junction coupling did not differ among the different types of lenses.

In all lenses studied before 2013, the intracellular pressure in lens surface cells was zero. Model calculations could not explain why the surface pressure needed to be zero; nevertheless, this was the consistent experimental observation. Our understanding changed when Sellitto et al. (25) found that mouse lenses engineered to lack PTEN, which is the phosphatase that counteracts phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), began to explode at 12 weeks of age. This occurred because the intracellular Δp in surface cells was not zero. Fig. 2 B shows the pressure gradients in wild-type and PTEN knockout lenses. The intracellular surface pressure, Δp, in the knockout lenses increased in an age-dependent manner to ∼50 mmHg by 10 weeks of age. This represents a near-maximum value of pressure since the lenses usually ruptured at around this age. The cause of the pressure increase was traced to accumulation of PI3K-mediated phosphorylation of AKT, which caused inhibition of the Na/K ATPase in the lens epithelium, thus reducing the osmotically driven efflux of water. The implication was that surface pressure is normally zero because of feedback regulation, which was interrupted in the PTEN knockout lenses. Our purpose in the current study was to investigate whether such a feedback system exists, and if so, to learn more about the underlying mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Lens preparation

In this study, we used mice with a C57 genetic background. The mice were painlessly euthanized in accordance with IACUC-approved procedures. Their eyes were then removed and placed in HEPES-buffered normal Tyrode solution containing (in mM) NaCl 137.7, NaOH 2.3, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, HEPES 5, and glucose 10, pH 7.4. To isolate and mount the lenses, the cornea, iris, and optic nerve were removed, and the sclera was cut into four flaps from the posterior surface. The lens was then transferred to a chamber with a Sylgard base, and the flaps of sclera were folded away from the lens and pinned to the base. The chamber was mounted on the stage of a microscope and perfused with Tyrode solution at room temperature.

Intracellular Δp measurements

Intracellular Δp was measured using a microelectrode/manometer system as described previously (14). In brief, microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl had resistances of 1.5–2.0 MΩ. The resistance was measured by passing square current pulses and recording the induced voltage. The resistance was first recorded in solution outside of the lens. The electrode was then inserted into the lens, where positive intracellular pressure pushed cytoplasm into the tip, causing the resistance to increase. The side port on the patch-clamp microelectrode holder was connected by plastic tubing to a mercury manometer. The pressure within the microelectrode was increased until cytoplasm was just pushed out of the electrode, and the electrode resistance returned to its original value measured in the bathing solution. This required final up-and-down fine adjustments until we could identify the pressure at which any small reduction would cause the resistance to increase slightly but a small increase in pressure would have no effect on resistance. This was the recorded value of intracellular pressure. The pressure in mmHg was read off of a mercury scale that went from ±400 mmHg in increments of 2 mmHg. Approximately 30% of the experiments failed because the microelectrode tip either broke or became clogged. This was usually obvious during the experiment, but could be confirmed at the conclusion of the experiment, when the resistance of the microelectrode was always remeasured in the bathing solution.

We were interested in determining the intracellular Δp in surface cells; however, it is not possible to place a microelectrode in one of these cells in an intact lens. The lens has a tough collagenous capsule, and when the microelectrode pops through the capsule it lands in fiber cells at least 20–30 μm away from the lens surface (r/a = 0.97–0.98). We cannot exactly control where it lands, and with such shallow penetrations it is difficult to measure the location accurately. At this distance into the lens, we measured a pressure of 15–20 mmHg (see Fig. 2). Since the pressure in the surface cells of wild-type lenses in control conditions was always zero, we subtracted the initial pressure in control conditions to obtain zero pressure as our initial estimate of surface cell pressure. When the experimental perturbation was made, we reported Δp relative to 0 mmHg. This should estimate the change in surface cell pressure. The data in each panel are presented as the mean ± SD for four lenses.

Pharmacological tools

Strophanthidin (Str; Sigma) was used to inhibit the Na/K ATPase at either a nonsaturating (0.2 mM) or saturating (4 mM) concentration. We could find no data on the half-saturating concentration of Str in mice, but in guinea pigs it has been reported to be ∼10 μM (26). In general, rats and mice have nearly an order of magnitude lower sensitivity to cardiac glycosides than guinea pigs, so we estimated the K0.5 to be ∼0.2 mM. This appears to be close, as the effect of 0.2 mM on surface pressure is about half that observed with 4 mM (see Figs. 3 B and 4 B). RN1734 (Tocris) or HC067047 (HC06; Tocris) was used at a concentration of 10 μM to inhibit TRPV4 channels (27). GSK1016790A (GSK; Sigma) was used at a concentration of 30 nM to stimulate TRPV4 channels (28). Ruthenium red (R-Red; Sigma) or A889425 (A88; Alamone) was used at a concentration of 10 μM to inhibit TRPV1 channels (29). Capsaicin (Cap; Sigma) was used at a concentration of 10 μM to stimulate TRPV1 channels (30). Akt inhibitor VIII (AKTi; EMD Millipore) was used at a concentration of 10 μM to inhibit AKT (23). All reagents were dissolved in DMSO before they were added to the bathing solutions.

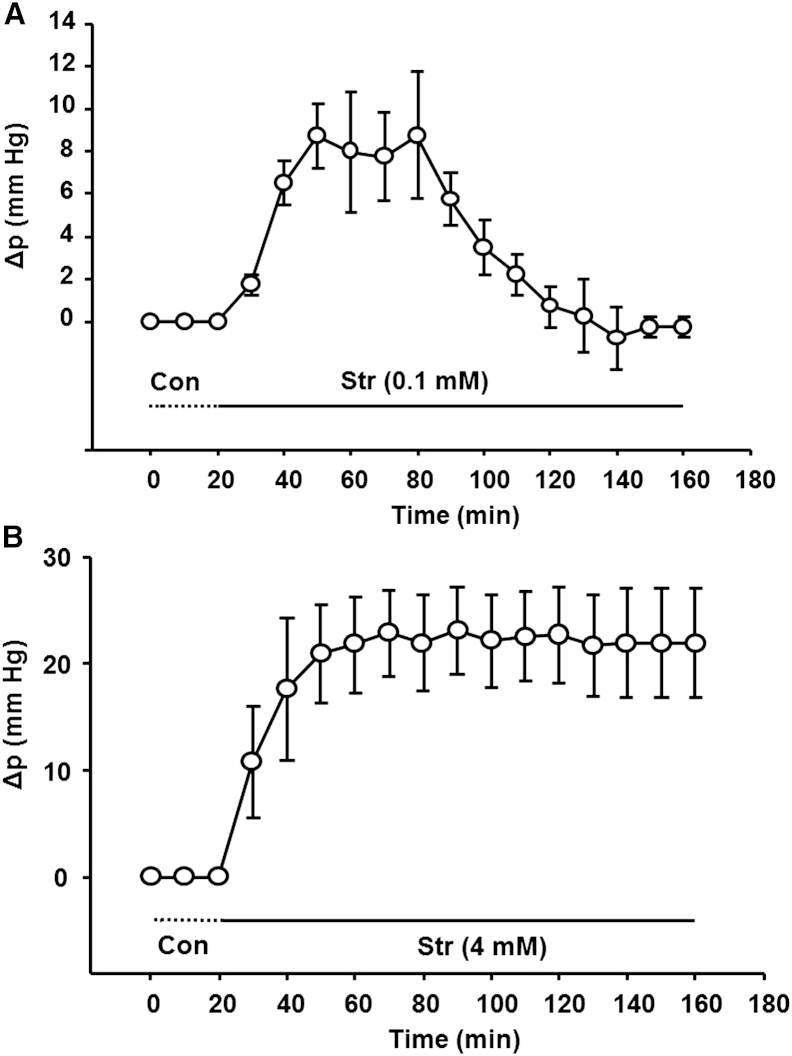

Figure 3.

Effect of the Na/K ATPase inhibitor Str on intracellular Δp in lens surface cells. (A) In lenses exposed to a nonsaturating concentration (0.2 mM), the pressure increases, but the pressure then returns to baseline, suggesting feedback regulation of positive pressure changes. (B) A saturating concentration of Str (4 mM) that abolishes essentially all Na/K ATPase activity caused a larger surface cell pressure increase that remained elevated.

Figure 4.

Role of TRPV4 in feedback regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells. (A) Activation of TRPV4 with GSK caused the surface cell pressure to decrease, but the pressure then returned to baseline in ∼2 h, suggesting feedback regulation of negative pressure. (B) Inhibition of TRPV4 with either RN1734 or NC06 prevented the return of pressure to baseline in lenses exposed to 0.2 mM Str. In the initial 20 min of the experiments, the inhibitors were added without Str being present, and there was no effect on pressure. This implies low basal activity when pressure is zero.

Results

Na/K ATPase regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells

Sellitto et al. (25) reported increased intracellular hydrostatic pressure in surface cells of PTEN knockout lenses, and attributed this increase to chronic inhibition of the Na/K ATPase. Here, the Na/K ATPase was acutely inhibited in a direct manner by exposure to Str, a highly specific inhibitor. Fig. 3 A shows the acute effect of a nonsaturating concentration of Str on surface cell pressure (Δp in Fig. 2 B). The pressure increases to a peak (∼8 mmHg) within 30 min of exposure, but then returns back to zero after ∼2 h. Since the dose of Str was not saturating, the observed return to baseline could be due to stimulation of the fraction of pump activity that remained unblocked, or to effects of other pathways downstream of the pumps. If all regulation were achieved through modulation of Na/K pump activity, a saturating concentration would not allow recovery. As can be seen in Fig. 3 B, a saturating Str concentration causes a much larger pressure increase (∼20 mmHg) than a nonsaturating concentration. Moreover, the pressure change does not return toward baseline.

The return to baseline shown in Fig. 3 A suggests feedback control of Δp, and based on Fig. 3 B, the feedback mechanism may act through regulation of Na/K ATPase activity. Studies by Shahidullah et al. (27, 28) showed that the mechanosensitive channel TRPV4 is expressed in the lens epithelium, and its activation, through a series of signal transduction steps, induces stimulation of Na/K ATPase activity. These observations motivated us to examine the role of TRPV4 in feedback restoration of pressure to baseline as shown in Fig. 3 A.

TRPV4 and regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells

If TRPV4 is the feedback sensor for positive surface cell pressure, its activation should cause the surface pressure to shift in a negative direction. This indeed is observed in Fig. 4 A, but the negative pressure returns to baseline after ∼2 h, suggesting feedback regulation of negative pressure deflections. If TRPV4 senses positive pressure and acts as the first step in a mechanism that stimulates Na/K pump activity to restore pressure to zero, inhibition of TRPV4 should break the feedback loop. As a consequence, the effect of nonsaturating Str should be a pressure increase that does not return to baseline. Fig. 4 B shows that in the presence of a TRPV4 antagonist (either RN1734 or NC06), partial inhibition of the Na/K ATPase with nonsaturating Str does indeed result in a persistent positive pressure. These data provide a solid link between TRPV4 and feedback regulation of positive pressure changes. Moreover, in the initial 20 min of the experiment, TRPV4 is inhibited without Str being present, and there is no effect on pressure. This implies that basal TRPV4 activity is low when pressure is stable at the zero steady-state value, and TRPV4 activation only occurs in response to positive pressure changes.

Since we have no evidence that TRPV4 responds to negative surface pressure changes, the return to baseline shown in Fig. 4 A is likely to involve a different pathway—one that inhibits Na/K pump activity. Work by Sellitto et al. (25) suggests that this pathway could involve activation of PI3K/AKT, which inhibits the Na/K pumps. However, these kinases are not known to be sensitive to Δp, so there would need to be a new pressure sensor that activates the PI3K/AKT path. A recent review of TRP channels in ocular tissues (31) described the effects of hyperosmotic and hyposmotic solutions on activation of TRPV1 and TRPV4, respectively. The results suggested that TRPV1 may be a sensor of negative pressure. TRPV1 is known to be present in the lens epithelium (32), so we examined TRPV1 inhibition and stimulation effects on surface cell pressure.

TRPV1 and regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells

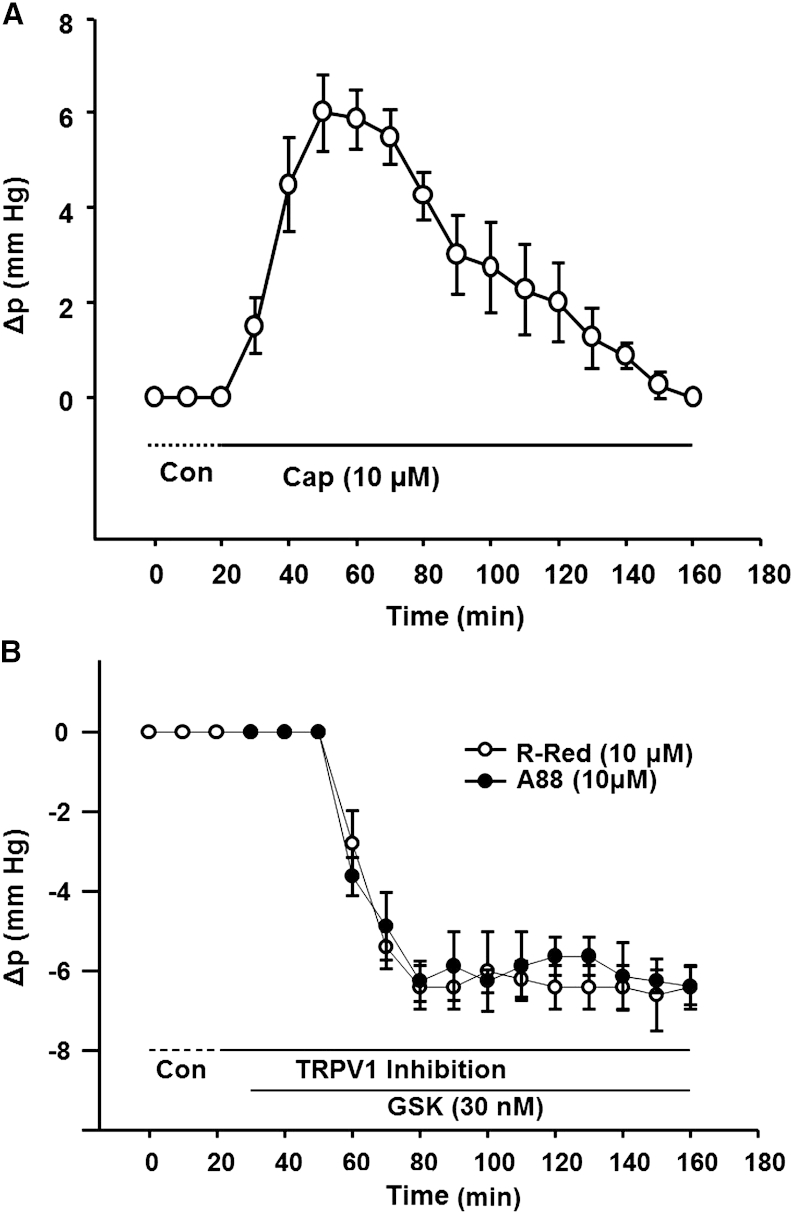

The studies shown in Fig. 5 were designed to test whether TRPV1 senses negative surface cell pressures and initiates a feedback cascade that returns pressure to baseline. If so, its activation should cause a positive pressure change due to inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity. Such a response was observed in lenses exposed to Cap, a highly selective TRPV1 agonist (Fig. 5 A). TRPV1 activation with Cap caused pressure to increase by ∼6 mmHg over a 30 min exposure. Subsequently, however, the pressure began to decline toward zero, and after ∼2 h the pressure returned to baseline. This is the predicted response if the positive pressure activates TRPV4 and stimulates Na/K pump activity to restore pressure to control levels.

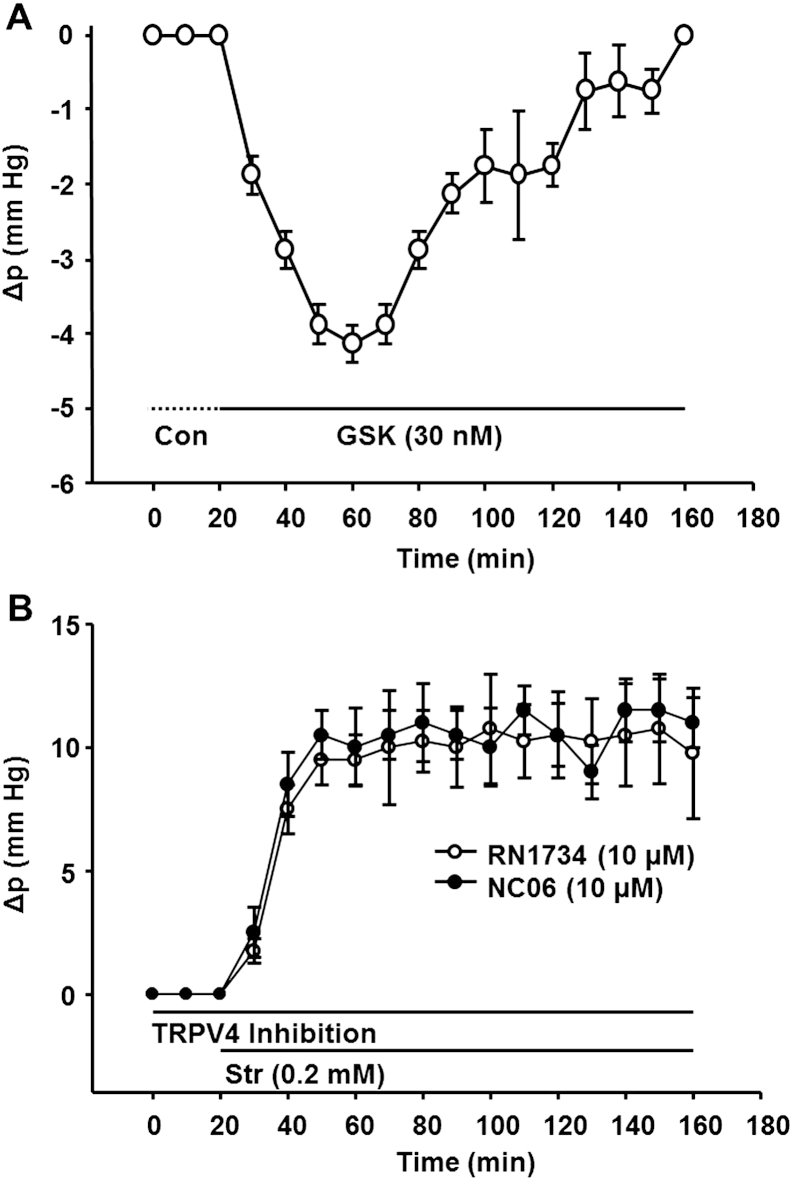

Figure 5.

Role of TRPV1 in feedback regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells. (A) Activation of TRPV1 with Cap caused pressure to increase, but it subsequently returned to baseline, presumably through activation of TRPV4. (B) Inhibition of TRPV1 with either R-Red or A88 caused no initial change in pressure, implying low basal activity when pressure is zero. However, subsequent activation of TRPV4 with GSK caused a negative pressure change that did not recover.

If TRPV1 senses negative pressure and acts as the first step in a feedback cascade that ultimately inhibits Na/K pump activity to restore pressure to zero, inhibition of TRPV1 with either R-Red or A88 should break the feedback loop. TRPV4 activation with GSK should then cause a pressure decrease that does not return to baseline (Fig. 5 B). This notion is consistent with TRPV1 being the sensor for feedback regulation of negative pressure. When either R-Red or A88 was initially applied and TRPV1 was inhibited, there was no effect on pressure, suggesting very low basal activity. As is the case with TRPV4, TRPV1 activity is not adjusted up or down—it is activated only by negative pressures and does not respond to positive pressures. The Na/K pump appears to be the component in this feedback system whose activity can be adjusted up or down in response to positive or negative pressure changes, respectively.

We initiated this study when Sellitto et al. (25) showed that pressure in surface cells does not always have to be zero. The positive pressure in surface cells of PTEN knockout mice was due to chronic activation of the PI3K/AKT axis, which was shown to cause inhibition of the Na/K pumps. It seemed likely that the acute effects of TRPV1 activation on surface cell Δp are exerted through the same pathway, but that remained to be demonstrated.

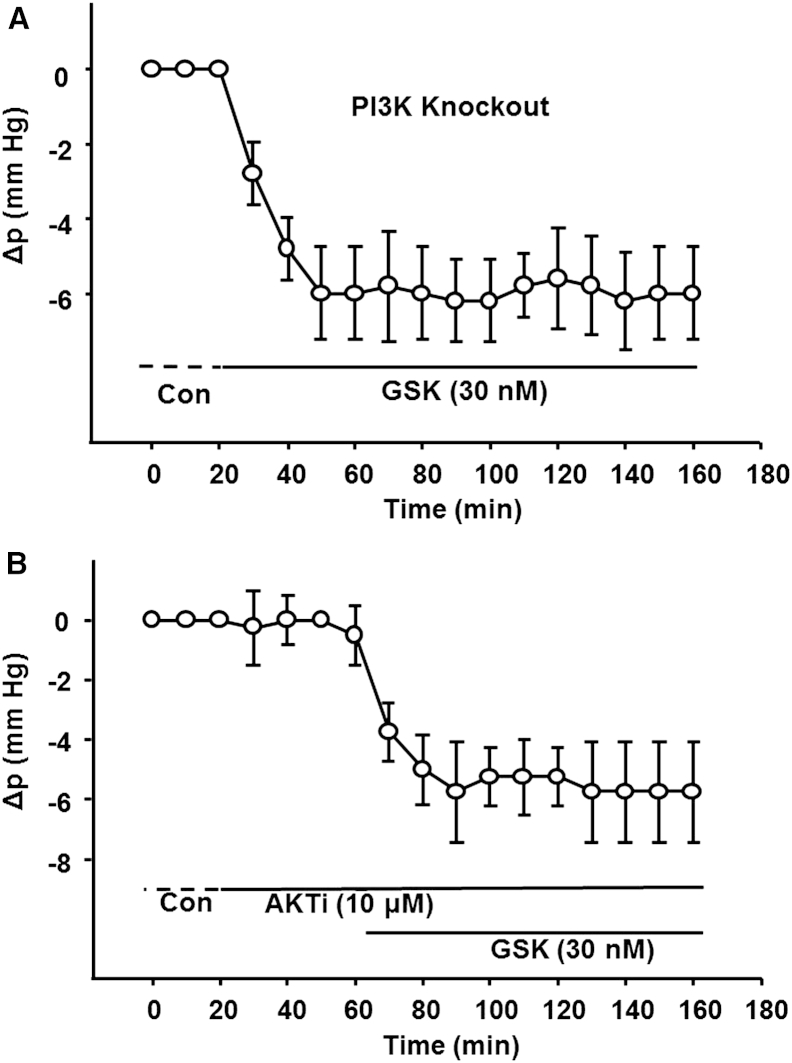

TRPV1 regulation of surface pressure depends on PI3K/AKT activation

White et al. (33) generated a lens-specific knockout of the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K. We used these mice to obtain the data in Fig. 6 A. In the absence of PI3K activity, TRPV4 activation with GSK caused a negative Δp that did not recover to baseline as it did in wild-type lenses (Fig. 4 A). This is consistent with PI3K being in the feedback loop initiated by TRPV1. These findings also suggest that activation of TRPV1 controls surface pressure by a mechanism that depends on PI3K activation to restore negative pressure changes back to zero. Presumably, this is a consequence of the blockade of PI3K/AKT-mediated inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity, as described in Sellitto et al. (25). To test this, we inhibited AKT activity with AKTi and then stimulated TRPV4 with GSK (Fig. 6 B). As in Fig. 6 A, the pressure decrease induced by stimulation of TRPV4 did not recover to zero. These data suggest that we are studying the same pathway as Sellitto and co-workers.

Figure 6.

TRPV1 feedback involves the PI3K/AKT axis. (A) Feedback recovery of negative pressure to baseline does not occur in PI3K null lenses. GSK was used to activate TRPV4 and cause the surface pressure to go negative. However, in contrast to the response of wild-type lenses (Fig. 4A), the pressure remained negative in the absence of PI3K. This implies that PI3K activation occurs in the feedback loop initiated by TRPV1 to restore pressure to baseline. (B) Feedback recovery of negative pressure to baseline did not occur when AKT was inhibited. Therefore, AKT activation also occurs in the feedback loop initiated by TRPV1 to restore pressure to baseline. Moreover, initial blockade of AKT with AKTi did not affect the control pressure. Together with our previous studies, this observation suggests that all feedback steps from TRPV1 activation through activation of AKT have low basal activity.

AKTi was applied for ∼20 min before introduction of GSK caused a negative change in pressure (Fig. 6 B). In this initial period, inhibition of AKT had no effect. Thus, in the feedback response to negative pressures, all steps from activation of TRPV1 through activation of AKT have low basal activity. Conversely, the Na/K pumps are always active and can adjust their activity up or down in response to positive or negative pressure changes, respectively.

Discussion

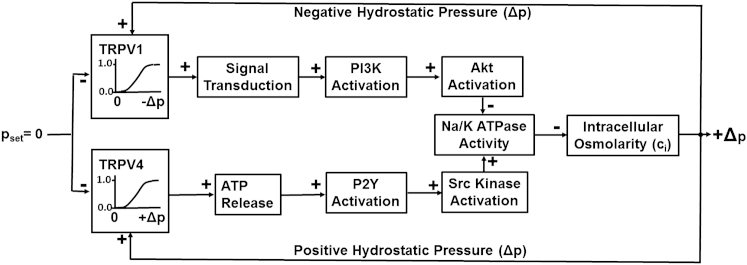

A feedback control system that summarizes the data presented here

The findings we have presented are consistent with the dual-loop local feedback control system sketched in Fig. 7. The setpoint pressure is on the left-hand side of the diagram (pset = 0). When the intracellular Δp in surface cells is zero, TRPV1 and TRPV4 are both inactive, and insofar as we could detect, downstream components up to the Na/K pumps are also inactive. The Na/K pumps are always active and, when Δp = 0, generate a transmembrane osmotic pressure that is just sufficient to drive the outflow of fluid, which enters the surface cell through gap junctions that couple surface cells (primarily equatorial epithelial cells) to the fiber cells in the volume of the lens (see Fig. 1 B). If some perturbation causes Δp to go positive, it is sensed by TRPV4 and, through activation of a series of transporters, the Na/K pumps are stimulated. A transient increase in transport of Na+ out of the lens reduces the intracellular osmolarity (hence the negative arrow connecting Na/K ATPase activity with osmolarity). The reduction in intracellular osmolarity increases the osmotically driven outflow of water and allows Δp to return to zero. If Δp goes negative, TRPV1 is activated and, through activation of a series of transporters, inhibits Na/K pump activity. Since increased activity reduces osmolarity (the negative arrow), a transient decrease in transport of Na+ out of the lens increases intracellular osmolarity, thus reducing the osmotically driven outflow and allowing Δp to return to zero.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the feedback control system, illustrating the mechanisms for regulation of intracellular Δp in lens surface cells. A positive arrow indicates that increased activity in the upstream block causes an increase of activity in the downstream block, and a negative arrow indicates that increased activity in the upstream block causes a decrease of activity in the downstream block. For example, an increase in Na/K ATPase activity due to Src activation causes a decrease in osmolarity, whereas inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity due to Akt activation causes an increase in osmolarity. In the TRPV1 initiated path, Akt activation inhibits Na/K pump activity; however, increased Na/K pump activation reduces intracellular osmolarity, so the result is inhibition of inhibition and is thus a stimulatory effect on osmolarity.

A number of steps in the signal transduction cascades have been omitted, either for simplicity or because they are unknown. Shahidullah et al. (27, 28) showed that lens TRPV4 is a Ca2+ channel and its activation causes a significant increase in intracellular calcium. This increase stimulates the opening of gap-junction hemichannels, which allow ATP to exit the epithelial cells. The increase in extracellular ATP activates P2Y receptors, as shown in Fig. 7 (for simplicity, the initial steps are not shown). The steps between Src kinase activation and stimulation of Na/K ATPase activity are not known. Even less is known about the upper feedback loop. The steps between TRPV1 activation and PI3K activation are not known, and we could find no information about them in the literature. Similarly, the steps between AKT activation and inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity are unknown and have not been described in the literature. Despite these gaps in knowledge, our data suggest that we have connected the input-output relationships. However, our data are based on acute pharmacological manipulations of TRPV1 and TRPV4, and this leaves a certain level of uncertainty. Knockout mice for TRPV1, TRPV4, and double TRPV1/TRPV4 have been generated and may provide a useful test of our model. Of course, these mice would show the long-term effects of a lack of TRPV activity rather than acute effects, but hypotheses only move forward when all tests are understood.

A biophysical model connecting Δp with Na/K ATPase activity

Fluid flows into a lens epithelial cell (see Fig. 1 B) through gap junctions that connect the epithelial cell with fiber cells throughout the volume of the lens. The fluid enters the fiber cells due to small transmembrane osmotic gradients created by the entry of Na+. A perturbation of the surface cell intracellular Δp would have little effect on fluid entry into fiber cells, so consider an idealized situation in which we assume there is no effect and fluid circulation is constant. At steady state, a constant fluid inflow, u (cm/s), is entering the epithelial cell and must be balanced by a constant outflow u. The steady-state outflow is given by

| (1) |

where L ((cm/s)/mmHg) is the epithelial cell membrane hydraulic conductivity and the transmembrane osmotic pressure Δc = ci − co, where ci is the intracellular osmolarity of the surface epithelial cell and co is the osmolarity of solution outside the lens. Thus, at steady state, Δp − RTΔc is approximately constant, and if Δc changes, so will Δp.

Similarly to fluid, Na+ flows into a lens epithelial cell (see Fig. 1 B) through gap junctions that connect the epithelial cell with fiber cells throughout the volume of the lens. Na+ is far from equilibrium, so its influx into fiber cells is nearly unidirectional and the intracellular sodium concentration in the epithelial cells [Na+]i (moles/cm3) has only a minor effect. Once again, for simplicity, consider an idealized situation where [Na+]i has no effect on influx. If a steady-state flux jNa (moles/(cm2s)) enters an epithelial cell from underlying fiber cells, it must be balanced by the same outflow through the Na/K pumps.

When TRPV1 was stimulated with Cap, as shown in Fig. 5 A, the Na/K pumps were inhibited; however, steady-state jNa was approximately constant, so [Na+]i increased until Na/K ATPase activity was restored to its original value where input = output. Since Na/K ATPase activity did not change, efflux and influx of K+ into the epithelial cells did not change (see Fig. 1 B), implying that [K+]i did not change. For electroneutrality, when [Na+]i increased, so did [Cl−]i, and hence Δc also increased. Equation 1 implies that to balance this increase in osmolarity and maintain constant fluid efflux, Δp increased as well. This would be the steady-state condition shown in Fig. 5 B. However, if Δp is sensed by TRPV4, Na/K ATPase activity will be reduced, and the opposite sequence will lead to an increase in [Na+]i and [Cl−]i until a steady state is reached in which Na/K ATPase activity and [Na+]i are restored to their initial values and Δp is once again zero. This is illustrated in Fig. 5 A.

What is being sensed by the TRP channels?

Feedback activation of either TRPV1 or TRPV4 restores both Δp and Δc to their original values, so either one could be the feedback parameter being sensed. However, early work on mechanosensitive channels (reviewed in Markin and Sachs (34)) indicated that strain, in either the cytoskeleton or membrane, initiated channel activity. Therefore, we choseΔp as the feedback variable in Fig. 7. We speculate that an increase in lens epithelial cell volume stretches cytoskeletal elements. This would require an opposing force, namely, positive Δp, so the actual feedback parameter may be the stretch of cytoskeletal springs around TRPV4, which is more directly related to Δp than toΔc. Moreover, when the lens epithelial cells shrink, cytoskeletal elements will be compressed, and this requires an opposing force, namely, negative Δp. Thus, the actual feedback parameter may be the compression of cytoskeletal springs around TRPV1, but again this is most directly related to a negative Δp. Pressure is a relative force, and a negative pressure in surface cells means that the pressure inside is less than the pressure outside, so one can think of the external pressure compressing cytoskeletal springs.

Thus, our working hypothesis involves the stretch and compression of cytoskeletal elements. Clearly, we have no direct evidence of cytoskeletal contributions, and this issue remains to be addressed in future studies.

What is the role of intracellular Δp in the lens?

The lens circulation comprises extracellular inflow and intracellular outflow of salt and water. The intracellular outflow of solution is mediated by gap junctions and driven by the intracellular pi gradient. Based on the data in Fig. 2 A and the results presented here, we conclude that the absolute values and parabolic radial dependence of lens intracellular pi have some intrinsically important role beyond simply driving center-to-surface fluid flow. We have no definitive answer as to what that role may be, but there are some experimental observations and model calculations that point to one interesting possibility.

All lenses have a spatial gradient in their index of refraction. The gradient is a parabolic function of radial distance from the lens center, with the highest value at the center (35, 36, 37). Without this gradient, we would barely be able to see. The gradient is thought to be generated by a radial gradient in intracellular protein concentration (reviewed in Sivak (38)). Since proteins cannot move through gap junctions, the protein concentration increases because water is drawn from the central cells. Water is in equilibrium when transmembrane hydrostatic and osmotic pressures balance, Δp − RTΔc = 0, and since water is always close to equilibrium (13, 39), osmolarity is clearly related to pressure. Hence, the refractive index gradient may be established by the intracellular pi. Consistent with this hypothesis, Vaghefi et al. (22) used magnetic resonance imaging to show that the protein concentration gradient in cow lenses collapsed significantly 2 h after the lens circulation was blocked. The most important physiological role of the lens is to focus light on the retina. Perhaps a specific radial profile of intracellular pi is an important factor in focusing light.

In the aging lens, gap-junction coupling conductance decreases dramatically, presumably due to oxidative damage to lens connexins. In mouse lenses, coupling was reduced 4-fold between the ages of 2 months and 14 months (40). All else being equal, this should have caused a 4-fold increase in the intracellular pressure gradient; however, intrinsic feedback mechanisms reduced the circulation of Na+ and fluid, so the pressure gradient increased by only 40%. The surface cell intracellular pressure remained zero at all ages. With age, the lens appears to compromise the circulation to maintain a more constant pressure gradient, though maintenance is not perfect. The refractive index gradient increases with age in mice (41) as it does in other species. The age-dependent decline in the optical efficiency of the lens may be driven in part by changes in the lens circulation. The evidence, however, is only correlative and more work needs to be done.

Remaining questions

The lens expresses a dual-loop feedback control system to maintain pressure in surface cells at 0 mmHg. The components of this system are found in most cells, and most cells have the ability to regulate their volume. Is this system expressed in other cells but has not yet been described? There have been numerous studies of cell volume regulation (reviewed in Hoffmann et al. (42)), and in general it was concluded that a regulatory volume decrease is mediated by opening K+ channels and activation of K/Cl cotransport, whereas a regulatory volume increase is mediated by opening Na+ channels and activation of Na/K/2Cl cotransport and Na/H exchange. In contrast, the system we have described appears to work entirely through stimulation or inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity.

We found no evidence that the cotransport systems mentioned above had any effect, but that does not rule out a possible role for these systems. When essentially all Na/K ATPase activity was abolished by a saturating concentration of Str, as shown in Fig. 3 B, the pressure became positive and there was no discernible restoration of pressure toward zero, as should have been seen if K+ channels had opened and K/Cl cotransport was activated. The lens is known to express the K/Cl cotransporter, and Chee et al. (43) showed that its long-term (18 h) inhibition or stimulation affected the lens cell volume; however, the effects had a complex dependence on where in the lens they looked. The lens is also known to express the Na/K/2Cl cotransporter (44), and we cannot rule out the possibility that it is activated in response to negative Δp in surface cells. However, our data suggest that activation of Na/K/2Cl cotransport would have to occur through the TRPV1 and PI3K/AKT pathway, since the negative pressures seen in Figs. 5 B and 6, A and B, remained constant when this pathway was blocked. This raises the question as to why the classic volume regulatory responses were not activated, or whether they were activated but had subtle effects.

A number of other questions came up as we began to characterize this feedback system. What other transporters are in the feedback loops that connect TRP channel activation to the Na/K ATPase? We are currently working on this question, but there are many possibilities to test. How is Na/K ATPase activity adjusted up and down? Does it occur through changes in localization due to trafficking of the pumps between the plasma membrane and a pool of endosomal vesicles? Is it achieved through a balance of kinase and phosphatase activity phosphorylating or dephosphorylating the pumps to alter their activity? TRPV1 and TRPV4 have been shown to respond to a variety of stimuli, including TRPV4 activation by UVB (45), which is obviously abundantly present in the optical axis. How are these various stimuli sorted out to produce a physiologically beneficial response? As usual, when a new system is revealed, new questions are also revealed.

Author Contributions

J.G. performed research and analyzed data. X.S. performed research. T.W.W. and N.A.D. contributed analytic tools and edited the manuscript. R.T.M. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through National Eye Institute grants EY06391 (R.T.M.), EY13163 (T.W.W.), and EY09532 (N.A.D.).

Editor: Miriam Goodman.

References

- 1.Griep A.E., Zhang P. Lens cell proliferation. In: Lovicu F.J., Robinson M.L., editors. Development of the Ocular Lens. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassnett S., Beebe D.C. Coincident loss of mitochondria and nuclei during lens fiber cell differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 1992;194:85–93. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001940202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs M.D., Soeller C., Donaldson P.J. Gap junction processing and redistribution revealed by quantitative optical measurements of connexin46 epitopes in the lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:191–199. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kistler J., Bullivant S. Protein processing in lens intercellular junctions: cleavage of MP70 to MP38. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;28:1687–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathias R.T., Kistler J., Donaldson P. The lens circulation. J. Membr. Biol. 2007;216:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson K.R., Patterson J.W. Localization of steady currents in the lens. Curr. Eye Res. 1982-1983;2:843–847. doi: 10.3109/02713688209020020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebihara L., Korzyukov Y., Tong J.J. Cx46 hemichannels contribute to the sodium leak conductance in lens fiber cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C506–C513. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00353.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldo G.J., Mathias R.T. Spatial variations in membrane properties in the intact rat lens. Biophys. J. 1992;63:518–529. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boswell B.A., Le A.C., Musil L.S. Upregulation and maintenance of gap junctional communication in lens cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Candia O.A., Zamudio A.C. Regional distribution of the Na(+) and K(+) currents around the crystalline lens of rabbit. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C252–C262. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00360.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao J., Sun X., Mathias R.T. Isoform-specific function and distribution of Na/K pumps in the frog lens epithelium. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;178:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s002320010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delamere N.A., Tamiya S. Expression, regulation and function of Na,K-ATPase in the lens. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004;23:593–615. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merriman-Smith R., Donaldson P., Kistler J. Differential expression of facilitative glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 in the lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999;40:3224–3230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merriman-Smith B.R., Krushinsky A., Donaldson P.J. Expression patterns for glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 in the normal rat lens and in models of diabetic cataract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:3458–3466. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B., Li L., Lim J.C. Dynamic regulation of GSH synthesis and uptake pathways in the rat lens epithelium. Exp. Eye Res. 2010;90:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim J., Lam Y.C., Donaldson P.J. Molecular characterization of the cystine/glutamate exchanger and the excitatory amino acid transporters in the rat lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:2869–2877. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim J., Lorentzen K.A., Donaldson P.J. Molecular identification and characterisation of the glycine transporter (GLYT1) and the glutamine/glutamate transporter (ASCT2) in the rat lens. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;83:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathias R.T. Steady-state voltages, ion fluxes, and volume regulation in syncytial tissues. Biophys. J. 1985;48:435–448. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83799-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donaldson P.J., Musil L.S., Mathias R.T. Point: a critical appraisal of the lens circulation model—an experimental paradigm for understanding the maintenance of lens transparency? Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:2303–2306. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beebe D.C., Truscott R.J. Counterpoint: the lens fluid circulation model—a critical appraisal. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:2306–2310. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5350a. discussion 2310–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J., Sun X., Mathias R.T. Lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure is generated by the circulation of sodium and modulated by gap junction coupling. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011;137:507–520. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaghefi E., Pontre B.P., Donaldson P.J. Visualizing ocular lens fluid dynamics using MRI: manipulation of steady state water content and water fluxes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011;301:R335–R342. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00173.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candia O.A., Mathias R., Gerometta R. Fluid circulation determined in the isolated bovine lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:7087–7096. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J., Sun X., Mathias R.T. The effect of size and species on lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:183–192. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellitto C., Li L., White T.W. AKT activation promotes PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome-associated cataract development. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:5401–5409. doi: 10.1172/JCI70437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levi A.J. The effect of strophanthidin on action potential, calcium current and contraction in isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 1991;443:1–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahidullah M., Mandal A., Delamere N.A. TRPV4 in porcine lens epithelium regulates hemichannel-mediated ATP release and Na-K-ATPase activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1751–C1761. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00010.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahidullah M., Mandal A., Delamere N.A. Hyposmotic stress causes ATP release and stimulates Na,K-ATPase activity in porcine lens. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012;227:1428–1437. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang F., Yang H., Reinach P.S. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation induces inflammatory cytokine release in corneal epithelium through MAPK signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:730–739. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sumioka T., Okada Y., Saika S. Impairment of corneal epithelial wound healing in a TRPV1-deficient mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:3295–3302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan Z., Yang H., Reinach P.S. Transient receptor potential (TRP) gene superfamily encoding cation channels. Hum. Genomics. 2011;5:108–116. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-2-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-García M.C., Martínez T., Merayo J. Differential expression and localization of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in rabbit and human eyes. Histol. Histopathol. 2013;28:1507–1516. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White T.W., Sellitto C., Lin R.Z. Interactions between gap junctional communication and phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in lens growth. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:3928. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markin V.S., Sachs F. Thermodynamics of mechanosensitivity. Phys. Biol. 2004;1:110–124. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/1/2/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierscionek B.K., Chan D.Y. Refractive index gradient of human lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1989;66:822–829. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierscionek B.K. The refractive index along the optic axis of the bovine lens. Eye (Lond.) 1995;9:776–782. doi: 10.1038/eye.1995.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones C.E., Atchison D.A., Pope J.M. Refractive index distribution and optical properties of the isolated human lens measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Vision Res. 2005;45:2352–2366. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivak J.G. The Glenn A. Fry Award Lecture: optics of the crystalline lens. Am. J. Optom. Physiol. Opt. 1985;62:299–308. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathias R.T., Wang H. Local osmosis and isotonic transport. J. Membr. Biol. 2005;208:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0817-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao J.H., Wang H., Mathias R.T. The effects of age on lens transport. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:7174–7187. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakraborty R., Lacy K.D., Pardue M.T. Refractive index measurement of the mouse crystalline lens using optical coherence tomography. Exp. Eye Res. 2014;125:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffmann E.K., Lambert I.H., Pedersen S.F. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chee K.S., Kistler J., Donaldson P.J. Roles for KCC transporters in the maintenance of lens transparency. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:673–682. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez L.J., Candia O.A., Polikoff L.A. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(−) cotransport activity in the rabbit lens. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;76:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore C., Cevikbas F., Liedtke B. UVB radiation generates sunburn pain and affects skin by activating epidermal TRPV4 ion channels and triggering endothelin-1 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3225–E3234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312933110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]